Comfortably cocooned: Onboard media and Sydney’s ongoing gridlock

Nicholas Richardson

University of New South Wales

Paul Ryder

University of New South Wales

Toot Toot, Chugga Chugga, Big Red Car

We’ll travel near and we’ll travel far

Toot Toot, Chugga Chugga, Big Red Car

We’re gonna ride the whole day long

(The Wiggles, 1998).

Abstract

Our paper argues that despite ubiquitous traffic jams, the automobile’s destructive impacts on urban milieu, and its significant contribution to global warming, Sydney-siders cling (and will likely continue to cling) doggedly to their vehicles. Founded on significant primary data sets, and employing a wide-ranging method assemblage approach, the paper posits that despite increasingly attractive public transport options, persistent, though evolving, mythologies mean that urban dwellers remain firmly ensconced in their automobiles. Among these powerful auto-centric mythologies is the notion of the car as a mechanism for near dwelling; an alternative home. As standards of interior appointment steadily improve, onboard media options have likewise evolved – to a point that even in the midst of gridlock and concomitant despair, we are ‘connected’ to a community of stop-start sojourners. Thus, in an ironic twist on Heidegger’s notion of dwelling, those on the road form roots that might not have otherwise have been formed. While we might no longer fly to our destinations (an auto-mythology of old), the paper suggests that we are, nonetheless, comfortably cocooned and (to a greater or lesser extent) connected with our fellow sufferers. The paper concludes that unless urban strategists confront these persistent, albeit transmogrified, mythologies, Sydney-siders and urban dwellers everywhere are unlikely to yield to logic and abandon their vehicles.

Getting underway

It is widely accepted that concentrated motorcar usage in major urban centres poses serious environmental challenges. In large measure, this is due to the resultant carbon emissions so central to the global warming debate (Chapman, 2007). But it is also due to the relentless development of motorway corridors that bisect urban and suburban spaces. Once habitable, these car-carrying canyons are now rendered fit only for those who, encased in metal, hurtle through them at great speeds (Ladd, 2008; Redshaw, 2008). Yet speeds are steadily diminishing. Within mere months, newly built highways promising the timely achievement of far-flung destinations become choked (Ting, 2016). Like so many of the world’s metropolises, Sydney is increasingly gridlocked —but even as (apparently) attractive public transport options open up, people doggedly cling to their cars.

Of course, no city is immune from the curse of traffic congestion but Sydney is nonetheless a relatively unique case. While Peter Newman and Jeffrey Kenworthy (2011; 2015) assert that automobile dependence has peaked in cities around Australia (and the world), this seems not to be the case in New South Wales’ capital where car use remains disproportionately high (Newman & Kenworthy, 2015). More than is the case elsewhere, then, planners in Sydney face the vexed question of how to get people out of their automobiles and onto trains, light rail, and buses. While there is an emerging consensus that the answer lies in the increased frequency of public transport services (Walker, 2012), we argue that the core of the issue lies elsewhere: in the powerful mythologies of the motorcar and in associated, deeply embedded, pro-automobile discourses. The song Big Red Car by Sydney-sider group The Wiggles expresses just some of these powerful narrative strains.

Catalysts

Notable catalysts for this paper were the somewhat unexpected findings of primary research conducted vis-a-vis rail infrastructure discourse in Sydney. The research consisted of qualitative surveys and focus groups with 152 public participants drawn from central, western and northwestern Sydney residents – as well as depth interviews with 30 public and private sector subject matter experts (SMEs): politicians; bureaucrats; television, radio and print journalists and editors; planners and architects; project managers; policy analysts and advisors; developers; builders; lawyers; financiers; and professional communicators. While the research aimed to understand just how media and public discourse influences rail infrastructure policy and projects, it soon became clear that a mythological omnipresence influences matters from the shadows. (1) Of course, that omnipresence is the automobile and its hold over Sydney-siders. While the original research paid only passing attention to the motorcar, in this paper we aim to give the subject the attention it deserves.

In a car you are physically cocooned … It is the last private place in an overwhelmingly public world … The worse it gets on the roads, the more we seek the solace of our vehicle. This is the way the world will end – trillions of us fleeing Armageddon, one per car (Jacobson, 1999).

The counter-discourses of the automobile’s detractors are well rehearsed. There is general agreement that the motorcar deracinates, dehumanises, and destroys (Berman, 1982; Fitzgerald, 1925; Forster, 1910; Grahame, 1908; Ladd, 2008; Redshaw, 2008; Ryder, 2013; Sachs, 1984; Woolf, 1925). However, in this paper we propose that it continues to be the evolution of dominant – albeit increasingly illusory – narratives of freedom that keep people cocooned in their cars. Moreover, through the prism of mythologies central to these narratives of freedom, we will reflect on the onboard media systems that play a crucial role in the ongoing reconfiguration of the automobile’s cabin as private dwelling place – making it less and less likely that people will uproot themselves from their private machines and take a bus. Putting it another way, we argue that complementing an already powerful set of referents is the automobile’s reconfiguration as home – a phenomenon that facilitates both personal entertainment and public engagement.

Supplementing the increasingly refined, Bluetooth integrated, onboard audio systems now supplied as standard in even the most ordinary of vehicles, the inventors of Siri (the voice recognition software embedded in Apple products) have taken that technology one step further. ‘Viv’, a new piece of software, is poised to replace searching, typing, and clicking and promises to reinvent the way we interface with the internet.

Elizabeth Dwoskin (2016) contends that Viv is one of a raft of software developments that will deliver the next big shift in computing and digital commerce itself. In a Sydney Morning Herald (SMH) article, Dwoskin outlines a successful attempt by Viv developers to place and complete a pizza delivery entirely through voice. Viv creator and chief executive Dag Kittlaus states: ‘It’s about taking the way that humans have naturally interacted with each other for thousands of years and applying that to the way they interact with services … Everyone knows how to hold a conversation.’ The possibility of turning ‘smart homes and cars and other devices into virtual assistants with supercharged conversational capabilities,’ will have considerable implications for the mediated spaces in which we dwell (Dwoskin, 2016).

And so we argue that, through onboard media especially, the car remains, and continues to evolve into, a preferred dwelling space irrespective of the growing gridlock beyond the glass and steel casing of the cocoon. Our argument is firmly situated in the arena of the ‘social’, rather than in the realm of economics or science in which the climate change debate has thus far been situated (Urry, 2011). In so doing, it adopts the approach of (and will refer to) Sydney-based socio-cultural research undertaken by Gordon Waitt and Theresa Harada (2012). In making our case, and in addition to referencing academic literature on car use and mining primary data sets, we leverage Roland Barthes’ famous essay on the Citröen, McLuhan’s Tetrad of Media Effects, and Martin Heidegger’s essay Building Dwelling Thinking (1951/1993, in Krell, 2011). Our approach is best described as what John Law (2004) terms a ‘method assemblage’: an eclectic mix of primary and secondary research including cultural engagement, literary reference, technical history, and philosophical conceptualisation. In intersection, this method assemblage facilitates the interrogation of complex, multi-faceted social domains.

Of course, in adopting this broadly triangulated method we acknowledge that we are contemporaneously producing just the multifaceted reality we seek to understand. Via this method assemblage, we nonetheless look to articulate ‘a sense of the world as an unformed but generative flux of forces and relations that work to produce particular realities’ (Law, 2004, p. 7). In the specific context of Sydney’s penchant for the car (a desire from which these Sydney-based authors are not immune), we assess deep-seated and transmuting mythologies that, against all reason, keep people firmly ensconced in their automobiles. As Barthes (1957/2009) famous exploration of mythologies demonstrates, the signs through which such mythologies are identified are deeply embedded socially and their traces are multifarious and often elusive in nature. It is for this reason that we have mobilised an assemblage of methods in order to tease out some understanding of the complex meanings at play. Overall, it is hoped that such an endeavour might influence the thinking of those committed to effecting behavioural change in the face of global warming.

Auto-mythologies

If automobility is to be understood as structuring environmental degradation then we have to pose the question: how and why did automobility come to be so dominant? … [A] common answer to this question is automobility arises as a more or less ‘natural’ extension of the human urge for freedom and the connection of that freedom to movement (Paterson, 2007, p. 29).

It is in the literature of Ancient Greece that the mythology of the automobile finds its earliest expression. As one of the present authors has observed, while ‘the sense of flight and escape suggested by the deus ex machina convention of classical drama is well recognised, less well known is the remarkable set of automobiles that, according to Homer, were created by the Greek fire-god Hephaestus’ (Ryder, 2013). In The Iliad, Hephaestus constructs 20 tripods (each with a set of wheels) that are propelled – cum impetu inestimabli – to a meeting of astonished immortals (op. cit.). Certain records of the Zhou dynasty notwithstanding (therein, a self-moved fire-cart is claimed to have been constructed three thousand years ago), and setting aside Cugnot’s three-wheeled steam-driven vehicle of 1769 and the traction engines that followed, humanity would have to wait until 1885 to see the dream of automobility realised.

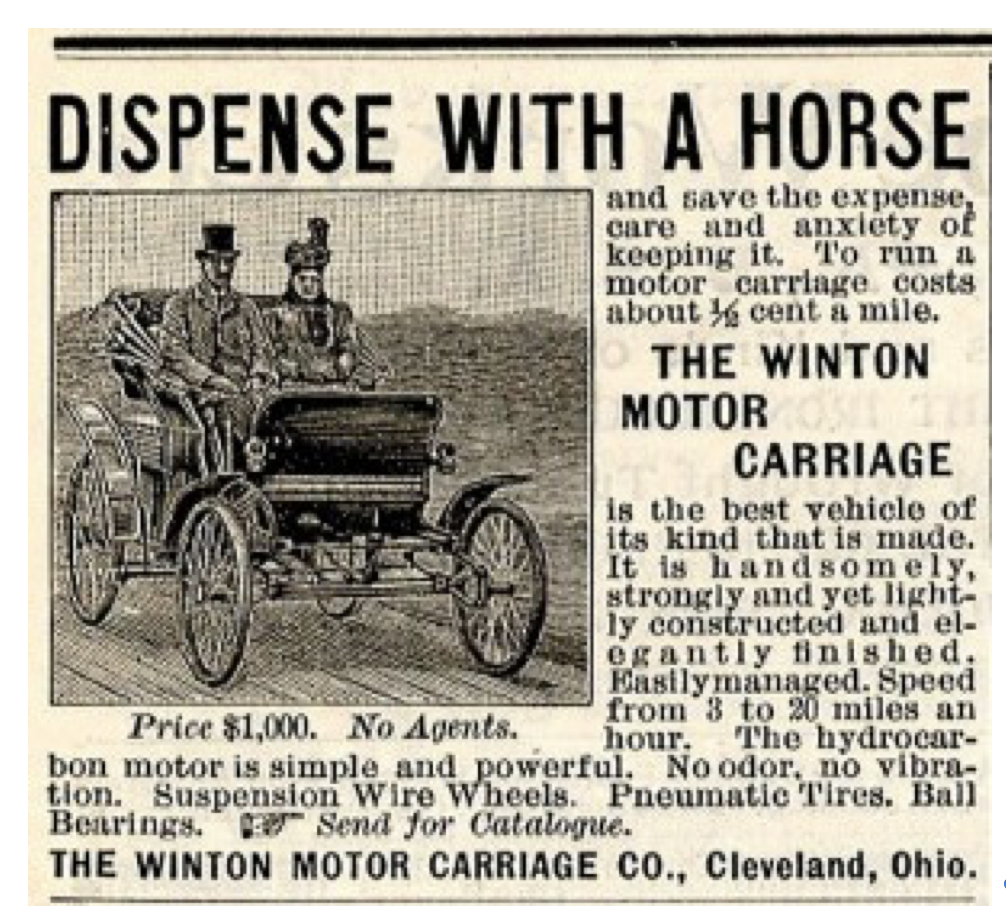

In that year, Karl Benz patented a three-wheeled ‘carriage with gas[oline] engine’: the world’s first motorcar. (Pizer, 1986, p. 29) In 1890, Gottileib Daimler produced his first motorcar: a four-wheeled forerunner to the modern car. Cultural responses to the motorcar were generally enthusiastic and, from the outset, advertisers made all kinds of appeals to all kinds of desires: the desire for the new; the desire for freedom (and magnified agency generally); the desire for ease and comfort; the desire for high fashion; the desire for reliability; and the desire for safety. But, above all others, the hunger for the new and the thirst for freedom are at the heart of the love of the automobile. (Sachs, p. 22) Long before the turn of the new century, the idea that innovation is its own reward had found its way into popular discourse. In the inaugural edition of The Auto Car, for example, the editor embraces the ‘horseless carriage’ as ‘the latest’ and, for that reason alone, worthy of celebration. (Sturmey, p. 1) On 4th February 1900, the following appeared in the News-Tribune:

There has always been at each decisive period in this world’s history some voice, some note that represented for the time being the prevailing power. There was a time when the supreme cry of authority was the lion’s roar. Then, came the voice of man. After that it was the crackle of fire …. And now, finally, there was heard in the streets of Detroit the murmur of this newest and most perfect of forces, the automobile … It was not like any other sound ever heard in this world …. It must be heard to be appreciated. And the sooner you hear its newest chuck! chuck! the sooner you will be in touch with civilisation’s latest lisp, its newest voice …’ (in Lacey, 1986, pp. 47-48).

The motorcar had been around for little more than a decade, but advertisers and journalists were already alive to the promise of the new and to the apparent freedoms that attend it. Ryder (2013) has noted that many other contemporary writers seized on the new aesthetic, embracing the motorcar as an emblem of amelioration. Among these was George Bernard Shaw who welcomed the motorcar as a sign of improvement and empowerment. The motorcar, Shaw wrote, ‘cannot be suppressed … It is improving our roads, improving the manners and screwing up the capacity and conduct of all who use them; improving our regulation of traffic, improving both locomotion and character as every victory over Nature finally improves the world and the race’ (Shaw, 1902/1967, p. 214). Here, amidst a broad celebration of technology’s power to enhance, is the superman ideal: the magnification of human strength. While Australian playwright Joseph (Bland) Holt was the first to put the motorcar on stage, as Ryder (2013) also notes, it is in Shaw’s 1902 play Man and Superman that the automobile is first presented as a sign of the elan vital.

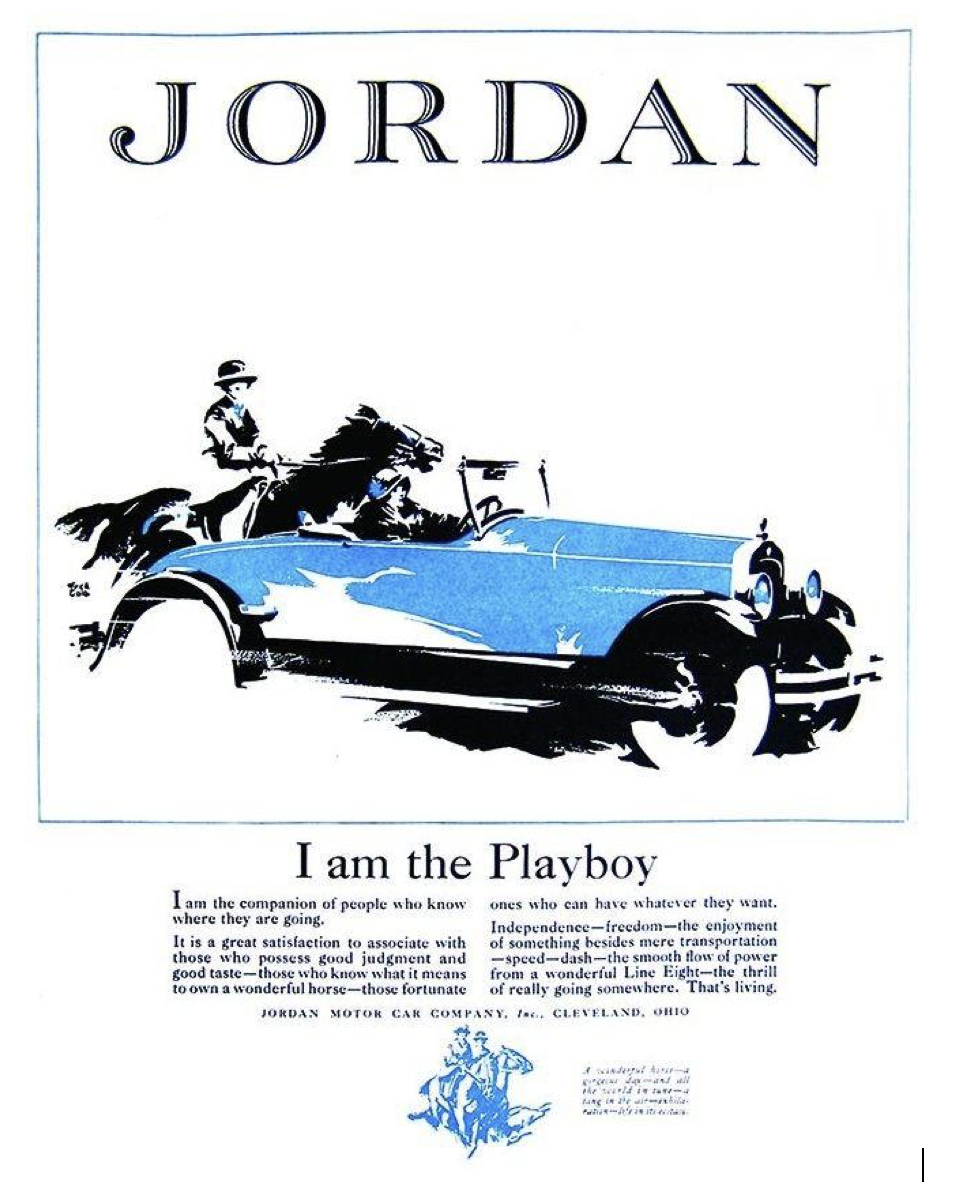

Similarly, Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) embraces the motorcar as an engine of magnification (for a time the Toad is positively animated by a machine that projects him into the world of men) while the Italian Futurists later seized on the car as an icon of liberty and as an expression of Nietzschean fantasies. Later still, in the mid-1920s, in his short fiction, F. Scott Fitzgerald positions the automobile as a sign of the new and utterly desirable. Indubitably, that aesthetic mutates in The Great Gatsby (1925) but, in the earlier part of that novel, as Ryder (2013) observes, the motorcar nonetheless shines forth as an emblem of extraordinary conquest. Published in the same year – but on the other side of the Atlantic – this aesthetic likewise finds expression in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway in which Septimus Smith hears in the sound of horns and motors the ‘anthem’ of his era: (Woolf, 1925/1989, p. 62) Forcing the horse into retirement, the automobile had become the new, soon to be ubiquitous, vehicle of social agency.

Figure 1: Out with the horse; in with the motor carriage

Figure 2: Freedom for all …

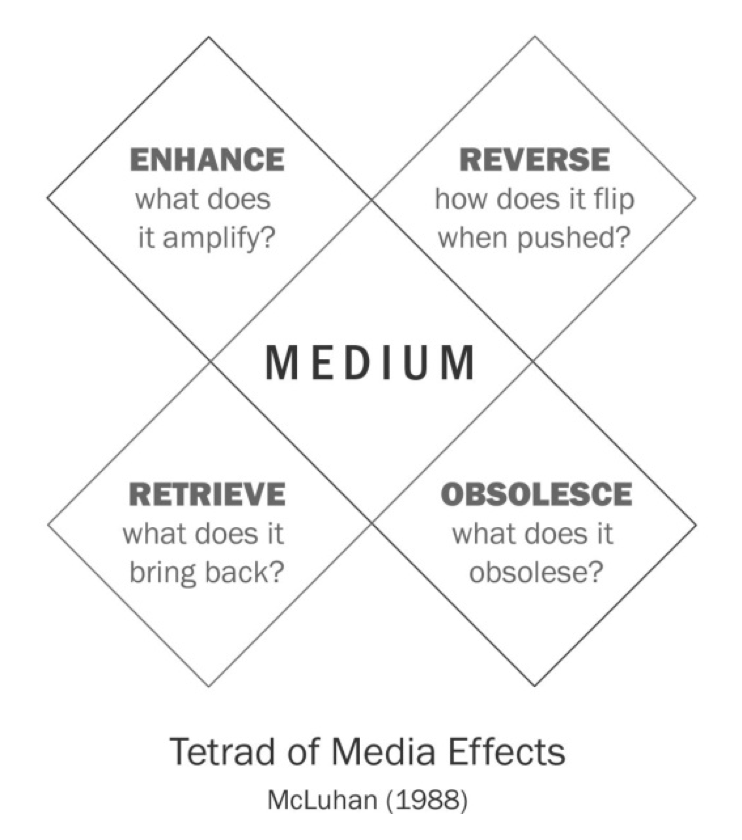

Thus, had it been earlier conjured, as the 20th century gathered momentum the motorcar would have seen the activation of the enhancement and obsolescence quadrants of McLuhan’s Tetrad of Media Effects (Fig 3) – a matrix that may be profitably applied to virtually any innovation.

Figure 3: Tetrad of Media Effects

The retrieval quadrant, too, would have been mobilised as the automobile became the vehicle for the newly mythologised knight-errant of the modern age. But even as the motorcar finally reversed into both gridlock and the tenebrous territory of the undertaker (the zone of reversal is the final quadrant of McLuhan’s tetrad shown in Figure 3) we contend that notions of enhancement and retrieval explain why the automobile remains an object of deep desire. It is a theme taken up in the 1950s by Roland Barthes.

In Mythologies, through his description of a new model by Citroën, Barthes (1957/2009) outlines the symbolic nature of the car. In his famous essay, Barthes compares cars to ‘great Gothic Cathedrals’, asserting them to be ‘the supreme creation of an era … consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object’ (p. 101). In asserting that through image and representation the car originates from heaven, Barthes positions the automobile as oblation. The ‘goddess’, he contends, is ‘mediatized’ through the car as object and symbol to become ‘the very essence of petit-bourgeois advancement’ (p. 103). In his piece on the automobile (and throughout Mythologies), Barthes contends that myths naturalise and purify; making things ‘innocent’, ‘giving them [things] a natural and eternal justification … a clarity which is not that of an explanation but that of a statement of fact’ (pp. 169-170). As Barthes states, the beauty of mythology is that ‘the meaning is already complete, it postulates a kind of knowledge, a past, a memory, a comparative order of facts, ideas, decisions’ (pp. 140-141). Later, in Mythos (1973), Dupré refers to myth as a ubiquitous, self-evident expression of the human condition (in van Binsbergen 2009, p.308) and, later still, Kolakowski (1984) defines it as a mental construct facilitating the retrieval of immutable truths (op. cit.). Wim van Binsbergen (2009) himself asserts that myth is often (too simply) considered ‘a collective representation’ (p.306). Calling for a more problematised perspective on mythology (op. cit.), among other things van Binsbergen opines that myths are often carried in narrative forms associated with a matter-of-fact, ‘truthful’ rendition. He further argues that they are commonly ‘reproduced’ [that is to say, as does Barthes in his essay on the Citroën, old mythologies manifest in new forms]. (p. 309) As an additional component of a more complex perspective on myth (again, Barthes does likewise), van Binsbergen argues that myth expresses a tension between the godlike and the human (p.314). We develop this point in the context of a closer examination of Barthes’ essay on the Citroën DS.

In French, ‘DS’ is pronounced as ‘Déesse’: goddess. The implication is that the machine is a manifestation of superhuman achievement. Having ‘fallen from the sky’ (perhaps the DS is the chariot of the classical deus ex machina?), it is also somehow prostituted: fallen, in a very different way, from the factories of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Thus, Barthes identifies the automobile as an object in mythological transition: now of the world, yet from the heavens (one of the several paradoxes explored is that the ‘alchemy of speed’ transmutes to ‘a relish in the pleasure of driving’), the motorcar is a form of heaven on earth.

Re-mythologising the car

Although Mythologies is clearly a celebration of myth, it also offers a sobering critique. A warning is found in Barthes’ assertion that although the beauty of myth lies in its capacity to unveil truths that seem immutable and beyond question, the danger is that we are lulled into a belief that things are black and white. In ‘passing from history to nature’, Barthes argues that myth abolishes the complexity of human acts, [giving] them the simplicity of essences.’ (1957/2009, p. 170) What myth instead organises is ‘a world which is without contradictions’ where ‘a blissful clarity’ is established in which ‘things appear to mean something by themselves’ (op. cit.).

Thus, through processes of mythologising (to which the motorcar is indubitably susceptible), certain truths may be privileged while others may be concealed. In a sense, as Barthes puts it, by mimicking a universal order that fixes a hierarchy of possessions, myth immobilises: thus, ‘every day and everywhere, man is stopped by myths, referred by them to this motionless prototype …’ (p. 183-184). Barthes’ words, then, signpost a more than minor sense of tension between the revealed and the concealed. This becomes important to our argument as we consider the following statement of Brian Ladd (2008):

A rational discussion about the merits of automobiles is scarcely possible. It is too hard to imagine our lives apart from our driving. Nor can we picture our cities and suburbs arranged around anything but highways and parking lots. Cars have fundamentally shaped our age …Once we have cars – and especially once there are nearly as many cars as drivers – we can fully benefit from the great convenience they offer. Yet as we organise our lives around their needs, the freedom they bring can begin to feel more like slavery (p. 2).

Here is a compounding of the problem outlined in this paper’s introduction. Despite the (ironically concealed) narratives of enhanced agency that lie at the heart of the automobile’s mythology, McLuhan’s notion of reversal resonates. For hours at a time, in Sydney and elsewhere, we are trapped in our vehicles and so the permanence of the myth meets the (very visible) permanence of gridlock. As the front page of the SMH of 11 March 2016 declares, we endure ‘Life in the slow lane’. The article that follows declares that over the last two years ‘peak-hour speeds on some of Sydney’s major roads have slumped by up to 25km/h [to just 46 km/h]’ and that ‘peak-hour is getting longer, with the worst afternoon peak…now spanning six hours’ (Ting, 2016). Furthermore, road accidents cause the death of approximately one person in NSW every day (Transport for NSW Centre for Road Safety, 2016). Motorised transport also contributes significantly to the air pollution that studies attribute to the premature deaths of 3000 Australians a year – at an estimated annual cost to the health system of $24.3 billion (Cormack, 2015).

Assuming viable alternatives, a rational person would, of course, abandon the car. But it is the very naturalness of mythologies (and less the absence of viable or equivalent alternatives) that ensures their stubborn hold. Myth manages to freeze in time a basal knowledge that disguises itself as natural to an object, cloaking it in meaning that becomes so normal that it ‘goes without saying’ (Barthes, 1957, p. 170). Myth therefore becomes a method for establishing this reality – this idea of permanence.

However, even as we glorify the car through mythologies of which we are scarcely conscious (and which we seldom interrogate), as suggested above, tensions emerge. These tensions are etched in sharp relief later when we turn to our primary research. When we press at its essence, the old form of the freedom narrative is rendered illusory and so, in Barthes’ piece, made modern, the chariot from the heavens transforms into a more utilitarian vehicle: ‘more homely, more attuned to this sublimation of the utensil which one also finds in the design of contemporary household equipment’ (p. 102). Myth mutates, and so while Barthes privileges the cutting-edge design of the Citroen DS, he acknowledges its genuflection to private domestic space: ‘The dashboard looks more like the working surface of a modern kitchen,’ he opines (pp. 102-103). And so, through this signification of domestic space, he asserts there is a ‘control exercised over motion’ (p. 103). The car is an object that now derives its meaning more through ‘comfort rather than performance’ (op. cit.).

Of course, this is not to suggest that the mystique of the speed/power myth is completely renounced. On the contrary, while we are drawn to consider new meanings, myths of amelioration, speed, and transcendence remain bright threads within a tapestry growing ever more rich and complex. As Jean Baudrillard (1968/2005) observed some years after the publication of Mythologies, ‘the motorcar may equally well be invested either with the meaning of power or with the meaning of refuge: it may be projectile or a dwelling-place’ (p. 74). So, automobile mythologies shift, almost imperceptibly, from the signification of speed, power and aggression to signs of domesticity, familiarity, comfort, order, and control – meanings all the more significant in these days of gridlock and delay.

This suggestion of domestic mobile space has deep cultural antecedents. As Ryder (2013) has noted, early as 1902, Bernard Shaw became the first writer to acknowledge that the automobile would replace bricks and mortar. In the figure of chauffeur Henry Straker, Shaw developed a character whose preferred habitat is the automobile. The character’s close identification with the car highlights his symbolic role as the new man of the twentieth century: the technologically literate individual whose being is predicated on the idea of both progress and domesticity. (See Ryder, 2013) Six years later, in The Wind in the Willows, through Toad’s canary-yellow cart, Kenneth Grahame foreshadowed a time when people would abandon their houses and dwell on the highways of England. Indeed, the same idea registers when the incarcerated Toad arranges his bedroom furniture in crude semblance of a motorcar. We once more see this ‘car as home’ theme in E. M. Forster’s Howards End in which the automobile becomes a semi-permanent residence for Charles Wilcox. The theme emerges again and again. As Ryder (2013) also observes, D. H. Lawrence also positions the automobile as a home away from home: in The Rainbow Skrebensky turns his car into a mobile bedroom in which to seduce Ursula; in Women in Love Gerald Crich turns his machine into a mobile office from which to confront protesters; in Lady Chatterly’s Lover, Clifford’s second home is his motorised cart – while, in the same novel, the automobile is Hilda’s definitive environment. Virginia Woolf, too, was aware of the automobile’s function as a home. In Mrs Dalloway (1925), for instance, the machine becomes (a rather depressing) waiting room for Lady Bradshaw.

In the mid-20th century, popular song also celebrated the benefits of the mobile home. Chuck Berry’s ‘No Money Down’ (1957) is probably the most striking example. The lyrics of this tune foreground an extraordinary array of features: power steering, power brakes, powerful engine, automatic heating, air conditioning, short wave radio, television, a full-length bed, and a telephone – so that Berry might talk to his baby. (op. cit.) The tune highlights a desire to abandon bricks and mortar in a machine that at once has all the comforts of home while facilitating unparalleled geographical freedoms. Motor size aside, perhaps Berry had in mind Volkswagen’s Kombi (1949-2013), which, following its American release the mid-1950s, sold in increasingly large number? While the geographical freedoms such as that afforded by the Kombi are now profoundly restricted (especially in city contexts), as is suggested by contemporary advertising, technological advancement is making possible a new kind of in-vehicle agency. In the advertisement for a driverless Volvo below, a reconfigured cockpit sees the pilot drawn well back from the controls – enjoying a read as his vehicle navigates the highway. Interesting to note is the impression of speed, afforded, these days, by fewer and fewer carriageways.

Figure 4: Volvo advertisement

Primary research findings

Our primary research suggests that the car profoundly influences both the way Sydney is shaped and the way it moves. Part of this research, an inner-city focus group discussion is particularly telling. In bemoaning the state of public transport, a respondent states that ‘if you’re going into Sydney’ then public transport is fine but ‘if you are trying to go anywhere through Sydney it’s an issue.’ Another respondent concurs, stating, ‘crossing town is a shocker,’ while a third declares: ‘you would only take your car.’ A fourth adds that if you [want] to go across the city ‘to a pub or a restaurant where you don’t want to drive home… get a taxi.’ Sydney, then, is a town shaped and inhabited according to road infrastructure.

Furthermore, as this focus group respondent exchange also suggests, even in the face of ever-increasing gridlock, the concept of freedom remains central to the mythology of the car in the Sydney context. Ultimately we find that this freedom manifests in three interrelated ways: the first is in the notion of customisable mobility; the second in the belief that the automobile levels up social inequalities; and the third in the generalised notion that the automobile somehow enhances human agency. Currently working as an advisor (in community consultation) to government and the private sector, these ideas are reflected in comments made by a former Sydney radio presenter. Arguing that the car has ‘become an expression of our individuality’, she also observes that ‘it becomes an extension of our personal space and [that] it’s even built around itself a little freedom narrative’:

So ‘I’m free in my car’ – and because of that there’s all sorts of political philosophies that you have built around the car…. And if you are reduced to being a commuter, so much of your personality is set aside it becomes like you are indistinguishable from the mob. It’s like ‘Who am I; I am not in my car; God all mighty how do I define myself?’ … it’s still that sort of domination of the idea of car ownership as a representation of so much of what we are as a society (Pers. Comms, 10/5/2013).

In his book Battlelines, supplanted Australian prime minster Tony Abbott also subscribes to the myth of automotive freedom. He asserts that ‘the sense of mastery that many people gain from their car,’ is often underestimated (Abbott, 2009, p. 174). ‘The humblest person,’ he opines, ‘is king in his own car’ (op. cit.). He continues: ‘Drivers choose the destination, the route, the time of departure, the music that’s played and whether they have company (op. cit.). Abbott, who lives in Sydney, encapsulates the persistent mythology of the motorcar. Now, more than 130 years since the birth of Benz’ machine (and given profound compromises to freedoms formerly afforded), on the face of it, it seems extraordinary that the myth of agency persists.

Our Sydney focus group data reflects the above sentiments. Despite problems of gridlock, rising toll prices, and the issue (and increasing cost) of parking, it also reveals that the automobile remains Sydney-siders’ preferred method of transport. In the inner city, this is particularly so for those travelling outside peak times or when crossing the Sydney CBD either laterally or along the North/South axis. The reasons are various: frustration with poor or slow public transport connections when passing through the city; (for respondents further out of the city), irritating gaps in public transport service (which reduce travel options and flexibility as well as increase travel times), and a belief that when using a car greater control is exercised over the travel experience itself. As an example of the former, a respondent from a public focus group held in Orchard Hills in Sydney’s outer western suburbs argues: ‘in this area there is still a lot of area that isn’t covered [by rail and bus connections].’ This also typifies sentiment from the Quakers Hill group in Sydney’s Northwest.

Both Orchard Hills and Quakers Hill focus group respondents raised concerns about safety, noise, and cleanliness as central to their rejection of public transport. ‘The trains are disgusting, they’re dirty, some people stink on them,’ said one Quakers Hill focus group respondent. ‘It’s scary on them [trains] at night. I don’t like it. It’s disgusting,’ said another. ‘A few weeks ago there was … something on the news about two kids that were bashed,’ adds another. In Orchard Hills the responses were similar. ‘There is too much violence on trains…now,’ said one respondent. ‘Last time I was on a train there was a graffiti artist straight there in front of my face,’ claims another. ‘These guys hold the doors open so they can smoke,’ objects a third. An elderly respondent bemoans the ‘noisy bloody school kids.’ The most pointed objection comes from an Orchard Hills focus group respondent who says, ‘you can’t blame public transport because it’s late or because there’s robberies. It’s the people in it – they’re crap.’

Recent media discourse adds to this perception. In an article published on the SMH online Bridie Smith (2016) highlights an international study (involving both Sydney and Melbourne) of germs found on public conveyances. While the article notes that most of the bacteria is harmless, this leading Sydney news site offers the following unfortunate headline: ‘The disgusting truth about germs on public transport.’ Clearly click bait, there can be little doubt that such constructions turn people off public transport and reorient them back to their own vehicles. As a Quakers Hill public research respondent states, ‘I would probably stay in my house everyday … I’m not going there if I can’t drive.’ Another Quakers Hill respondent asserts, ‘I prefer to drive because to me it feels like it’s safer. Even though it takes me so long to get into the city I prefer that than public transport.’ A central Sydney respondent contends that there is no evident solution to car dependency: ‘it doesn’t matter how much the commute time increases, people would much rather be in their car.’ Another recently published article by the SMH’s Matt O’Sullivan tells just this tale (14 August, 2016).

Objections matching those of the above respondents may likewise be found in earlier research, including Waitt and Haradas’ 2012 project on car usage in the southern Sydney suburb of Burraneer Bay. Similar sentiments are to be found in the expert opinions embedded in our own research. One such respondent, an eminent Sydney architect and planner, states:

There are huge anti-public transport feelings … they say ‘we never catch public transport’ but they would rather sit in a traffic jam for hours… people won’t [catch a train] because it’s demeaning or something. They’d rather sit in their Merc (Pers. Comms, 22/3/2013).

Likeminded responses are also reflected in broader scholarship on the subject. Present in the literature reviewed in the introduction, they are also present in research that specifically investigates the car and public transport usage. As Brain Ladd (2008) states:

… mobility is freedom – freedom is mobility – and before the car, mobility was unavailable, or slow, or (as with trains) dependent on the whim or goodwill of others. No wonder cars have the power to stir the blood like no other modern invention (p. 1).

Implicit in the above observation is that control over frequency is of real moment. Indeed, Jarrett Walker (2012) suggests that the key issue in modern ‘human transit’ planning is ‘frequency’. Frequency is ‘the main measure of everyone’s least favorite phase’ of a trip: ‘waiting’ (p. 85) Frequency, of course, is the aspect of transport where the car is without equal. As a Quakers Hill respondent states, ‘they [trains and buses] don’t run to fit your schedule, they run to their time schedule… so it doesn’t have that flexibility like your own personal car.’ Frequency is also a clear explanation for the central Sydney groups’ concerns over connection problems associated with crossing the city in public transport. As one respondent states, ‘I wouldn’t even consider going across town [without a car].’

Suggested here is a very considerable problem for Sydney: until the public transit system reaches something like the levels of ‘frequency’ of the car, perhaps all is lost? It is, however, not even as simple as that. While public transport frequencies should of course be improved and ‘rapid transit’ made a priority, there remains the problem of breaking down the mythologically-inspired hold of the car. As a central Sydney respondent states, ‘even if you can demonstrate that it’s quicker to go by public transport [people] will still prefer taking their car.’ An expert respondent, a television journalist, expresses a similar sentiment when she states, ‘people think, ‘yes we need more public transport for other people to catch, but I would like to have my car because of the freedom of it’ (Pers. Comms, 21/5/2013). Indeed, so powerful is the mythology of the automobile that pro-automobile discourses find their way even into the rhetoric of public transport proponents. Commenting in response to the 2008 NSW Government announcement of the (now abandoned) Sydney City Metro project, Christopher Brown, Managing Director of the Tourism and Transport Forum, offers this: ‘we’re just delighted that finally we’re getting a metro system, replacing the old Kingswood with a Ferrari’ (Ralston & Rose, 2008, March 18).

One of the greatest ironies of the motorcar’s mythology is its ability to veil the single most appreciable obstacle to the car as an agent of freedom: gridlock. So pervasive is gridlock that the phenomenon has, for a long time, been culturally registered. Referring to the 1963 documentary Le Joli Mai, Baudrillard (2005/1968) writes:

I have no good moments … except for those I spend between my house and my office. I drive; I drive. These days, though, I am simply not happy even then, because there is too much traffic (p. 71).

As suggested by the current WestConnex projects in Sydney, the answer appears to be to build more roads and to widen existing ones – yet a number of the expert respondents in our research point to the irony that building roads actually exacerbates the traffic problem. As an expert respondent involved in the M5 East car tunnel project says: ‘on the day it opened, there was a ten-percent drop in passengers on the eastern rail line. What a perverse piece of public policy’ (Pers. Comms, 20/12/2012).In Car Sick, Lynn Sloman (2006) elucidates this mythology: the illusory ‘naturalness’ of road development:

This is madness. The problem for technocrats is that they have come to believe that increasing car use is an immutable fact of modern life. They fail to recognize that it is the policy choices made in the last forty years that have created the world we live in today. They look at the historic traffic trends – the result of disastrous policies of the last forty years – and extend those trends indefinitely into the future, and then they say, ‘if traffic is going to rise, we will have to make room for it.’ What they have done is to confuse cause and effect. They see traffic growth as a natural phenomenon, to which their bypasses and relief roads and multi-storey car parks were a response (p. 13).

The above statement also suggests that myth veils deep contradictions, ensuring that the ‘technocrats’ fail to recognize ‘that the bypasses and relief roads and multi-storey car parks, and the rash of car-scale development that they enabled, [make] driving more attractive and other means of travel unpleasant’ (Sloman, 2006, p. 13).

If, as Matthew Paterson (2007) argues, it is the case that ‘the rise of the car as a “natural” expression of human autonomy may be fairly quickly dismissed’ (p. 29), why is that we build more roads and so favour the automobile over other forms of transport? There are, of course, many reasons – but the most powerful are rooted in pervasive noetic and emotional narratives: long-held beliefs about the automobile; auto-centric mythologies with profoundly sticky referents.

So it is that, despite significant diminishments and curtailments, in our imaginations and in our collective memory we remain ‘free’ in our cars. We may travel when we wish, though not as fast as we wish, in a vehicle surveilled a little more than we might wish – but which is, nonetheless, more-or-less indexical of our financial agency and (accordingly) more or less tailored to our comforts. Indeed, we contend that only the last of these might properly explain the persistent lure of the automobile in gridlocked urban environments such as Sydney. In this connection, we argue that the deeper mythologies of the automobile have metamorphosed. Far from its capacity to conquer the highway – and here we return to a theme adumbrated earlier in this paper – the freedom of the automobile is now a function of the extent to which it may be configured as home; as a socially conspicuous site of entertainment and relaxation that reinforces what Matthew Paterson (2007) calls capitalism’s ‘regime of accumulation’ (p. 30).

The car as cocoon

In the process of travel we temporarily submit ourselves to become part of a mobile collective (Bissell, 2010, p. 270).

It is with the above tenet of mobility studies in mind that we now explore the paradox of car travel as part of an ever-expanding network of drivers – while the car’s cabin remains a site of homely comfort and isolation. We propose that this is partly due to the cabin’s recent reconfiguration as an integrated media hub. In other words, since the advent of the radio (and in the context of new, sought-after integrated media technologies) the car has been increasingly configured as a hermetically sealed cocoon in which one might immerse oneself in a tailored entertainment experience even while one’s interaction with the wider network of road users is unavoidable. This desire for entertainment finds expression in a diary entry made by a respondent in Waitt and Harada’s south Sydney study:

Traffic very heavy due to long weekend, but listened to radio and music. Thoroughly enjoyed being back in the smooth, quiet, cocooned comfort of the X5 [BMW four-wheel drive]. Nice relaxing journey despite the traffic (Waitt & Harada, 2012, p. 318).

While the cabin is here configured as a place of peace, ironically, in order to satisfy the demands of high performance aficionados, the (externally recorded) sound of BMW’s new generation bi-turbo V8 (as installed in its current F10 M5 model) is piped into the car’s cabin via the vehicle’s audio system. Car and Driver’s K.C. Colwell (2012) puts it thus:

[BMW’s] engineers discovered that the F10 chassis, like that of so many other new cars these days, is so effective at insulating the cabin from road and engine noise that the M5 lost … its bark [that is, the roar of the previous, naturally aspirated, E60 V10].

Channeling, once more, McLuhan’s Tetrad of Media Effects (Fig 3), in a bid to entertain, the new model’s cabin pays homage to technologies unlikely to grace the earth again. Thus, in a new chassis, old mythologies – in the form of the rawer sounds of freedom so enthusiastically celebrated by the Italian Futurists over one hundred years ago – are retrieved at the press of a button.

This is all an expression of Baudrillard’s (2005/1968) contention that the car (while ‘an object in full stagnation’ and ‘[m]ore and more abstracted from its social function of transportation’) is ‘transformed, reformed, and metamorphosed madly’ (p. 178). Despite the reality of tear-inducing traffic congestion, through its various onboard and remote technologies, the automobile continues to offer perceptions of freedom. Resonating, more than ever, is the old adage that it is the journey, and not the destination, that counts.

Of course, technologies such as the telephone and the radio have long since contributed to a reconfiguring of the automobile as a living and working space. While some of the early literature has been traced, more recently Eric Laurier (2004) studies the automobile as an extended place in which to undertake work. Meanwhile, Michael Bull (2001; 2004) discusses the importance of sounds – and music in particular – to the ability of the driver to ‘orchestrate’ a journey. Similarly, when Tony Abbott states that ‘[t]he humblest person is king in his own car’ (2009, p. 174), he offers as evidence the driver’s control over music played and the company kept. In Mobilities (2007), John Urry likewise proposes the car to be ‘a strong kind of contemporary dwelling’ (1999, p. 129) and argues that due to the control over ‘the social mix’ afforded a driver in his or her car, ‘dwelling-on-the-road’ has changed to ‘dwelling-in-the-car’ (p. 9). Central to Urry’s argument is media technology:

The car radio connects the ‘home’ of the car to that of the world beyond, a kind of mobile connected presence. Almost better than ‘home’ itself, the car enables a purer immersion in those sounds, as the voices of the radio (and the hands-free phone) and the sound of music are right there, in the car, travelling with one as some of the most dangerous places on earth are negotiated (Urry, 2007, p. 129).

Here, Urry pinpoints an interesting mythology surrounding the car; one that we assert is becoming increasingly important for its continuing dominion. In a similar vein, Michael Bull’s research suggests a tension between ‘retreat’ (once meant as an escape into ‘places of silence, to be alone with one’s thoughts’) and ‘car habitation… infused with multiple sounds’ (2001, p. 187). Bull argues that ‘the aural privacy of the automobile is gained precisely through the exorcising of the random sounds of the environment by the mediated sound of the cassette or radio (p. 187). To this, we might add the sound of deliberately ‘piped’ engine noise or the eruptions of the hands-free telephone as it rings through the cabin (to be answered, of course, at the touch of a button on a programmed steering wheel). All this takes place in a space where seats may be electronically tailored to the contours of one’s body and where cabin temperature may be preset via mobile application so that, when we arrive at the vehicle, the engine is running and the interior welcoming.

Returning to the radio, Bull’s thesis is essentially that we retreat into its sounds: particularly music. It is the invention of the radio, he contends, that marks Urry’s historical turning point between ‘dwelling-on-the-road’ and ‘dwelling-in-the-car’ (Bull, 2001, p. 188). As Bull (2001) states:

More recently the car as ‘home’ is described as becoming increasingly filled with gadgets to make the driver feel even more at ‘home’. Automobiles are increasingly represented as safe technological zones protecting the driver from the road and, paradoxically, from themselves (p. 187)

Bull’s argument that sound is key to this expression of dwelling hinges on his assertion that many drivers are not in fact comfortable ‘spending time in their cars with only the sound of the engine to accompany’ (p.189). His point that for these drivers the radio facilitates ‘dwelling’ in the sense of community (or, at least, invisible but audible community) is one well made. One of Bull’s research respondents states: ‘It’s lonely in the car. I like to have music.’ (Bull, 2001, p. 192). Another asserts: ‘the talking stations are very much to key yourself into the world,’ while a third says, ‘it connects me to the world because you’ve got someone talking to you’ (op. cit.). There is no surprise here. The automobile was always about connection over multiple horizons, but as physical (point-to-point) connection grows more and more difficult (courtesy of the traffic-jam), we now more abstractly connect via our cars. And so Bull concludes that to redress an otherwise nightmarish squandering of time as we crawl along in heavy traffic, the radio (in particular) allows us to reclaim a sense of significant present (p. 199).

In a later piece, Bull (2004) more clearly ties this reclamation of significance to notions of control when he states that ‘the management of experience through sound technologies is tied to implicit forms of control: control over oneself, others and the spaces passed through’ (p.248). Here, then, is another retrieval – this time of control lost in the tedium of the traffic jam: we may not be able to drive in the old sense, yet ‘time possessed [in the cocoon of the cabin] is more likely to be time enjoyed’ (op. cit.). Developing his argument, Bull turns to the use of mobile phone which, he suggests, facilitates the remediation of the journey ‘into intimate ‘one to one’ time’:

The automobile becomes a mobile, privatized and sophisticated communication machine through which the driver can choose whether to work, socialize or pass the time … the aural space of the automobile is perceived as a safe and intimate environment in which the mobile and contingent nature of the journey is experienced precisely as its opposite, in which the driver controls the journey precisely by controlling the inner environment of the automobile through sound (2004, p. 251).

Our own research suggests that for those trapped in ‘the great Sydney car park’ – as one focus group respondent called peak hour gridlock – the radio entertains and offers updates on the extent of the problem. It is telling that while popular mythology has it that legacy media is in decline, today in Australia (and internationally) radio has not in fact suffered the diminished attention experienced that seems to be the assumption with legacy media of its kind (Anonymous, 2016). Much of this is due to the phenomenon of ‘drive time’ in which radio offers relief and an avenue through which to vent frustration (Anonymous, 2015).

Interviewed in our primary research, a former Sydney radio presenter contends that radio is absolutely complicit in the problem of public transport discourse because one of the main reasons for radio’s success is its availability in the car:

Radio stations are even a bit caught up in all of this because what do people do when they are sitting in their cars? Well, they listen to their radio. And that means that radio stations get more listeners because people are in their cars. The whole traffic network thing is built around the idea of traffic (Pers. Comm., 10/5/2013).

Our primary research also highlights a discourse of disparagement directed against those outside the drive-time caller clique. A woman in one Quakers Hill focus group states:

There’s actually people out there that belittle people that catch public transport. They downgrade them … that was on [2Day FM radio station in Sydney] 104.1 [with presenters] Kyle and Jackie O … People are more judgemental now. Yes because you can’t afford to like have your own car and stuff. It was on 104.1. People were ringing up saying that yes they agree they laugh at people when they get wet on the side of the – you know when they are waiting for a bus.

It may be argued, then, that life in Sydney’s slow lanes is a catalyst for a community of like-minded individuals and that onboard media – especially the radio – is the conduit for such connection.

However, in light of Bissell’s recent work on the nature of ‘near-dwelling’ involved in mobilities, there is perhaps a larger point to be made. In his 2013 article ‘Pointless Mobilities: Rethinking Proximity Through the Loops of Neighbourhood’, Bissell argues that proximity has traditionally been taken to be something actively pursued in order for mobility to take place: that is, we consciously connect together with people in order to travel from point to point. Bissell instead contends that proximity is something far more passive; that proximity is merely a by-product of mobility itself. He argues that the proximity required in near-dwelling is not then ‘underpinned by an ontology of connection, but an ontology of exposure which is more attuned to thinking about how relations of bodies and their near-dwellers are sculpted in the event of being mobile itself’ (p. 352).

Bissell (2013) makes this point in order to argue for a ‘transversal proximity’ that describes ‘relations with other near-dwellers that cut across the path of travel and, in doing so, spotlights transformations that happen whilst on the move’ (p. 357, italics in original). Bissell proffers the metaphor of ‘the loop’ as a way of tracing these transversal proximities. He states:

[R]ather than being orientated towards a specific point, however mobile or fluid that point might be… the loop circumvents points of departure and origin and instead prioritises the passage. In the loop, rather than following a bearing of there-and-back (which is orientated by the pivot of the turning-point), one is always simultaneously facing the point of departure and arrival, which has the effect of creating a very different sense of orientation. … In contrast to being orientated towards a point, the loop is a deviation that, on the face of it, defies productivism, economy and efficiency in the same way that going around in circles is suggestive of not going anywhere. (p. 358)

Bissell’s work on ‘the loop’ then provides an interesting way of apprehending ‘a kind of intimacy that is gained through movement,’ which is certainly applicable to near-dwelling radio and onboard media (p. 359). However, we engage this metaphor not only to foreground the near-dwelling made possible by the car’s cabin, but to the shifting mythologies shared by motoring near-dwellers more broadly. As Bissell states, ‘the transversal encounter with the near-dweller that the loop generates brings about a kind of movement-knowledge where the loop becomes a way of getting to know the depths and folds of territory through movement’ (p. 359). Furthermore, he states, ‘it is the repetition of journeys that gives rise to loops in time,’ and with this ‘repetition of everyday mobilities’ Bissell suggests ‘that transversal proximity changes through repetition’ – and that through these changes an impression of the collective arises that is ‘much more fluid, transitional and plastic’ (p. 359, italics in original).

Seen through this lens, to both paraphrase and quote Bissell, our project has been one of considering how loopsintersect; how they ‘speak to and resonate with one another’; how they ‘hang heavy with the past’; and how the loops of the past relate to loops of the present – and almost inevitably relate to loops of the future. (pp. 359-360). This is, of course, precisely how mythologies evolve.

Conclusion

Our assemblage of primary and secondary texts points to the galvanizing force of the car. As drivers manoevre for a few extra metres of diminishing road space (even as that space momentarily magnifies when new roads are built) they come together through media as a community of fellow sufferers seeking to navigate through gridlock, or at least to commune – accidentally or not – in spite of it. To this end, the automobile becomes more than a space of transit. Through their onboard media technologies and the connections thus facilitated, a near-dwelling beyond the imaginations of either Benz or Daimler is made possible.

In July 2016 Volkswagen launched a television advertising campaign for its Polo model in Australia. (2) In the advertisement, a driving mother is about to ask Siri (Apple’s soon to be outdated voice activation software) where something is, and before she can finish the question her daughter in the backseat cuts in with the word ‘ice-cream’. Siri responds with directions to ice-cream. The car is already morphing from comfortable locus to something akin to personal assistant. With Viv on the horizon (the earlier noted software that signals new levels of voice-activated connectivity and agency), and as innovation makes the car less an assistant and more of a companion (think social media connectivity) we wonder how this perception of the automobile as comfortable cocoon may ever be reversed?

While no longer able to ‘hold back tears [of frustration] and step on the gas’ – as Marshall Berman (1982, p. 291) famously put it – like Danny DeVito’s inimitable character Ernest Tilley in the 1987 film Tin Men we may at least recline the seat of our automobile and sink down in a welter of despair and recrimination. Complain we might, but at least comfortably cocooned in the precisely configured luxury of our car’s cabin. Thus, through a re-inscribing of the motorcar myth, we have an enhanced dwelling place – and it is this that makes the work of those trying to avoid the symptoms of carsickness so impossible. Rather than logics that may be dismantled (who, on the face of it, would not abandon the car?), urban designers are up against the weight of transmuting mythologies and persistent prejudices. They are also up against the very concept of dwelling, the tentacular roots of which are as deep as humankind’s first societies. In the automobile of the twenty-first century we have a highly sophisticated unitary cocoon that may, through mobile applications and a vast array of onboard technologies, be precisely tailored not only to our individual physical needs but also to the social demand for community. Who, we ask, might so dwell on a bus or train?

In his 1954 essay Building Dwelling Thinking, Martin Heidegger argues that dwelling involves far more than habitation: rather, it necessitates a deep connection of the self and place through neighbourly engagement. (in Krell, 2011, p. 245) With the motorcar once registering as the very antithesis of such a concept of dwelling – a cultural rootlessness that Heidegger ties to nothing less than the business of inauthentic being – the argument is changed up by the reconfiguration of the automobile as home. In the car of today (and tomorrow) we have a place for both self-reflection and neighbourly interaction: a cocoon in which we may more or less authentically dwell. Paul Virilio’s (1986) assertion that vehicular power is everywhere ‘repressed and reduced’ (p. 141) is manifestly correct, but he errs when he argues that the myth of the car is condemned to disappear. Rather, and virtually unnoticed, the car has silently slid into reconfigured mythic milieu where freedoms of old have been retrieved and transmogrified. Emphases have shifted from the destination to the journey; from the external to the internal; from the concrete to the abstract. While the tear-inducing anguish of gridlock on paved carriageways remains, courtesy of the car’s re-configured cockpit the daily grind is increasingly bearable. We may no longer fly to our destinations but, as we crawl along roads that just yesterday facilitated the exhilaration associated with speed, we are, on the other hand, comfortably cocooned and most certainly well connected.

References

Abbott, T. (2009). Battlelines. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Anonymous. (2015) ‘Listening summary, commercial radio Australian 2014. Commercial Radio Australia. Retrieved 14/1/2016 from http://www.radioitsalovething.com.au/RIALT/media/RIALT/PDF/Listening-Summary_2014_Ver2-2_2.pdf?ext=.pdf

Anonymous. (2016 January 5) ‘Radio: Fighting a problem of perception’ retrieved 15/01/2016 from http://www.medialifemagazine.com/radio-fighting-problem-perception/

Barthes, R. (1957/2009) Mythologies. London: Random House.

Baudrillard, J. (1968/2005) The system of objects. London/New York: Verso.

Berman, M. (1982/1988) All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity. London: Penguin.

Bissell, D (2010). ‘Passenger mobilities: affective atmospheres and the sociality of public transport’ Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28, pages 270-289.

Bissell, D (2013). ‘Pointless Mobilities: Rethinking Proximity Through the Loops of Neighbourhood’ Mobilities, 8(3), 349-367.

Bull, M. (2001) ‘Soundscapes of the car: a critical study of automobile habitation.’ In D., Miller ed. Car cultures (Materializing culture). Oxford: Berg.

Bull, M. (2004). ‘Automobility and the power of sound’. Theory Culture & Society, 21(4-5), 243-259.

Chapman, L. (2007) ‘Transport and climate change: a review’, Journal of Transport Geography, 15(5), pp. 354–367.

Colwell, K., C. (2012 April) ‘Faking it: engine-sound enhancement explained’, Car and Driver. Retrieved from http://www.caranddriver.com/features/faking-it-engine-sound-enhancement-explained-tech-dept

Cormack, L. (2015, November 4) 3000 deaths caused by air pollution each year prompt calls for tougher standards. SMH Online. Retrieved 11/9/2017 from http://www.smh.com.au/environment/3000-deaths-caused-by-air-pollution-each-year-prompt-calls-for-tougher-standards-20151113-gkygv1.html

Cox, C.B. & Dyson, A.E., eds. The Twentieth Century Mind: History, Ideas, and Literature in Britain. London: OUP.

Dwoskin, E. (2016, May 5) Siri’s creators say they’ve made something even better. SMH Online. Retrieved 5/8/2016 from http://www.smh.com.au/technology/innovation/siris-creators-say-theyve-made-something-even-better-20160505-gomwkn.html

Forster, E. M. (1910/1981) Howards End. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Fitzgerald, S. F. (1925/1990) The Great Gatsby. London: Penguin.

Grahame, K. (1908/1980) The Wind in the Willows. NY: Methuen.

Jacobson, H. (1999 December 8) ‘Road rage’. The Independent Online. Retrieved 11/3/2016 from http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/road-rage-1130921.html

Krell, D. [ed.] (2011) Heidegger: Basic Writings. London: Routledge

Ladd, B. (2008). Autophobia: Love and hate in the automotive age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lacey, R. (1986). Ford: The Men and the Machine. London: Heineman.

Laurier, E. (2004). ‘Doing office work on the motorway?’ Theory, Culture and Society, 21(4-5), 261-277.

Law, J. (2004). After method: mess in social science research. New York: Routledge.

Lawrence, D. H. (1928/1961) Lady Chatterly’s Lover. London: Ace/Harborough.

_____________ (1915/1970) The Rainbow. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

_____________ (1920/1992) Women in Love. London: Wordsworth Classics.

Newman, P. & Kenworthy, J. (2011). Peak car use: Understanding the demise of automobile dependence. World Transport Policy and Practice, 17(2), 32–42.

Newman, P. & Kenworthy, J. R. (2015). The End of Automobile Dependence: How Cities Are Moving Beyond Car-Based Planning. Washington, DC: Island Press.

O’Sullivan, M. (2016, July 19). WestConnex: Extra tunnel, road widening makes $16.8b motorway even bigger. SMH Online. Retrieved 20/7/2016 from http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/westconnex-extra-tunnel-road-widening-makes-168b-motorway-even-bigger-20160718-gq8mae.html

____________. (2016, August 14). Two or three-car families new norm in Sydney despite public transport increase. SMH online. Retrieved 26/8/2016 from http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/two-or-threecar-families-new-norm-in-sydney-despite-public-transport-increase-20160805-gqm4qw.html

Paterson, M. (2007). Automobile politics: ecology and cultural political economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pizer, V. (1986). The Irrepressible Automobile. NY: Dodd Mead & Co.

Ralston, N., & Rose, D. (2008, March 18). Sydney to get metro rail system. SMH Online. Retrieved 17/4/2012 from http://news.smh.com.au/national/sydney-to-get-metro-rail-system-20080318-2042.html

Redshaw, S. (2008). In the company of cars: Driving as a social and cultural practice (Human factors in road and rail transport). Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Pub.

Richardson, N. J. (2015a). Political Upheaval in Australia: Media, Foucault and Shocking Policy Proceedings ANZCA Conference 2015, Queenstown, New Zealand, 8 Jul 2015-10 Jul 2015.

Richardson N.J. (2015b). A Curatorial Turn in Policy Development? Managing the Changing Nature of Policymaking Subject to Mediatisation M/C Journal 18(4) 20.

Ryder, P. (2013). The Motorcar and Desire: A cultural and literary reconsideration of the motorcar in modernity, Southern Semiotic Review, Vol. 2. Online: http://www.southernsemioticreview.net/the-motorcar-and-desire-a-cultural-and-literary-reconsideration-of-the-motorcar-in-modernity-by-paul-ryder/

Sachs, W. (1984/1992). For Love of the Automobile: Looking Back into the History of Our Desires. Trans. Reneau. D. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Shaw, G. B. (1902/1967). Man and Superman. London: Longmans.

Sloman, L. (2006). Car sick: Solutions for our car-addicted culture. Dartington: Green Books.

Smith, B. (2016, June 28). The disgusting truth about germs on public transport. SMH Online Retrieved 28/6/2016 from http://www.smh.com.au/national/health/the-disgusting-truth-about-germs-on-public-transport-20160627-gpsw2x.html

Sturmey, H. [ed] (1895, 02 Nov.) Editorial. The Auto Car: A journal published in the interests of the mechanically propelled road carriage. No. 1. Vol. 1.

Ting, I. (2016, March 11). Life in the slow lane. SMH Online. Retrieved 11/3/2016 from http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/peak-hour-in-sydney-is-getting-worse–and-longer-data-shows-20160310-gnftvd.html

Transport for NSW Centre for Road Safety (2016) NSW road fatalities report. Retrieved from http://roadsafety.transport.nsw.gov.au/downloads/road-fatalities-2106.pdf

Urry, J. (1999) Automobility, car culture and weightless travel: A discussion paper. Department of Sociology, Lancaster University, Lancaster. Retrieved 22/3/2016 from http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/resources/sociology-online-papers/papers/urry-automobility.pdf

Urry, J. (2007). Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity.

Urry. J (2011). Climate Change and Society. Cambridge: Polity.

Valentine, J. (2016, February 12). James Valentine: The podcast, ABC.net. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2016/02/12/4405704.htm

van Binsbergen, W. (2009). Rupture and Fusion in the Approach to Myth: Situating Myth Analysis Between Philosophy, Poetics and Long-Range Historical Reconstruction. Religion Compass 3/2. pp.303–336.

Virilio, P. (1986/2006). Speed and Politics. Trans. Polizzotti, M. Los Angeles: Semiotexte.

Waitt, G., & Harada, T. (2012). Driving cities and changing climates.’ Urban Studies, 49(15) 3307–3325.

Walker, J. (2012). Human transit: How clearer thinking about public transit can enrich our communities and our lives. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Woolf, V. (1925/1989). Mrs Dalloway. London: Grafton.

About the authors

Dr Nicholas Richardson is lecturer in media at the University of New South Wales. He teaches strategic and creative communication. His research pursues two streams of interest. One stream is focused on communications surrounding policy development – key actors and influences – with particular focus on transport infrastructure. The other stream focuses on pitching creative commercial work and the development and articulation of creative concepts for commercial endeavours.

Contact: nicholas.richardson@unsw.edu.au School of the Arts & Media UNSW, Sydney

Dr Paul Ryder is a strategist and lecturer in media at the University of New South Wales where he teaches commercial, advertising, and communication strategy. He is interested in how deep-seated principles of military strategy manifest in response to a range of contemporary problems. Having written a doctoral dissertation on the mythologies of the automobile, he is also writing and co-authoring a series of related articles – this paper included.

Contact: p.ryder@unsw.edu.au School of the Arts & Media UNSW, Sydney