Don’t publish and be damned: An advocacy media case study

Don’t publish and be damned: An advocacy media case study

and

School of Communication Studies

Auckland University of Technology

Abstract:

Advocacy journalism is practised by a wide range of mainstream media publishers and broadcasters and alternative media outlets. It is a genre of journalism that is fact-based but supports a specific viewpoint on an issue. It is generally in opposition to so-called objective journalism. Likewise, advocacy advertising is used to espouse a point of view about controversial public issues. It can be used to target consumer groups, government agencies, special groups or market competitors. Independent student journalism publishing also often challenges normative values. Advocacy advertising, or social issues marketing, was the brief for five shortlisted groups of Auckland University of Technology advertising creativity students on behalf of a New Zealand lobby and protest movement called Homeowners Against Line Trespassers (HALT) in September 2006. HALT was campaigning against a controversial proposal by the state-owned enterprise Transpower to build a 400kV transmission line across a 200km route from Otahuhu to Whakamaru in the Waikato as part of a new national pylons network. Three campaign advertisements were created by a pair of students for AUT’s journalism training newspaper, Te Waha Nui, and a separate single advertisement was designed by a second pair of students for an Auckland metropolitan billboard and postcard campaign. This article examines advocacy media in the context of the HALT campaign that explored research links between power pylons and public health and the dynamic with student editors that led to non-publication of the professionally selected social issues message.

Introduction

While the global press was “distinctly partisan” well into the 19th century, objectivity

norms eventually dominated and today define the ethos of the corporate and

commercial news media. But this objectivity standard has been increasingly seen by a

growing body of journalists as, at best, inadequate as a norm for contemporary

journalism, or seriously flawed (see Berman, 2004; Careless, 2000; Jensen, 2007;

Johnson, 2007; Solomon, 2006). Since the 1970s, advocacy journalism has emerged

whereby journalists identify with a particular view yet remain independent. Advocacy

journalism is practised by a wide range of mainstream media publishers and

broadcasters and alternative media outlets. It is a genre of journalism that is fact-based

but supports a specific viewpoint on an issue. It is generally in opposition to so-called

objective journalism.

Likewise, advocacy advertising or social issues marketing are practices used to espouse a point of view about controversial public issues (Berney, 2007; Fram et al., 1993; Jackall & Hirota, 2003). Social marketing applies traditional marketing methods including planning, pricing, communication and research to bring about behaviour change that will benefit society. The term “social marketing” was first published in 1971 by Kotler and Zaltman (p. 42) but the concept was originally proposed by the sociologist G. D. Wiebe in the 1950s (Siegel & Lotenberg, 2007, p. 203). Andreason (1995) defined social marketing as:

The application of commercial marketing technologies to the analysis, planning, execution, and evaluation of programmes designed to influence the voluntary behavior of target audiences in order to improve their personal welfare and that of their society. (p. 7)

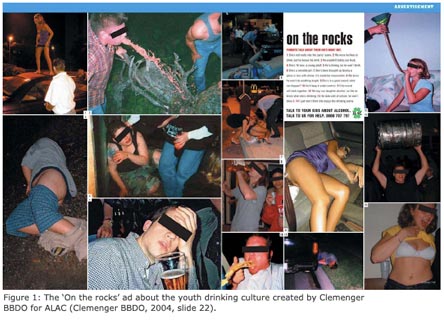

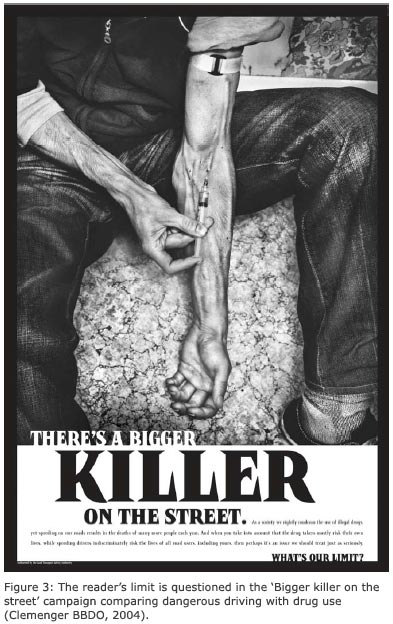

Advocacy advertising can be used to target consumer groups, government agencies, special groups or market competitors. An example of this is an Alcohol Advisory Council (ALAC, 2005) campaign—“It’s not the drinking, it’s how we’re drinking”— which aims to shift people’s attitudes to their involvement with alcohol. Significant funding supports this multimedia campaign that targets specific demographic groupings with a variety of resonating and graphic messages. Another is the graphic road accident ads created as part of the campaign for the Land Transport Safety Authority (LTSA).

Independent student journalism publishing also often challenges normative values. Advocacy advertising/social issues advertising was the brief for five shortlisted groups of Auckland University of Technology advertising creativity students on behalf of a New Zealand lobby and protest movement called Homeowners Against Line Trespassers (HALT) in September 2006. HALT was campaigning against a controversial proposal by the state-owned enterprise (SOE) Transpower to build a 400kV transmission line across a 200km route from Otahuhu to Whakamaru in the Waikato as part of a new national pylons network.

Three campaign advertisements were created by a pair of students for Auckland University of Technology’s journalism training newspaper, Te Waha Nui, and another single advertisement was designed by a second pair of students for an Auckland billboard and postcard campaign. Te Waha Nui was founded in 2003 and has been published regularly since as an innovative newspaper in both tabloid print and online editions. It has frequently adopted causes and diversity objectives while remaining independent (Robie, 2006a; Boyd-Bell, 2008). This article examines advocacy media in the context of a HALT advertisement that campaigned over research links between power pylons and public health and the dynamic with student editors that led to nonpublication of the professionally selected social issues message.

Advocacy journalism

According to media analyst Robert McChesney, the global media environment has

experienced a major paradigm shift. In place of informed debate and political parties

organising along the full spectrum of opinion, there is “vacuous journalism and

elections, dominated by public relations, big money, moronic political advertising and

limited debate on tangible issues”.

It is a world where depoliticisation runs rampant, and a world where the wealthy few face fewer and fewer political challenges. It is because of this context that many people around the world are organising to reform their media systems to better serve the democratic needs of the great mass of citizens. (McChesney & Nichols, 2002, p. 96)

Contemporary journalism involves the social responsibility theory of the press by citing the “public’s right to know” as its mantra (Protess et al, 1991, p. 13). For example, after the Washington Post’s expose of the Watergate affair, the newspaper adopted an ethical code pledging “an aggressive, responsible and fair pursuit of the truth without any fear of any special interest, and with favour to none” (p. 14).

Some see investigative journalism and the “mobilisation model”—a notion that media exposes lead to public policy reforms by changing public opinion—as a form of advocacy journalism (Protess, p. 15). Others do not share this view. Canberra Times editor Jack Waterford, for example, does not regard advocacy journalism—where a reporter who supports some programme of policy “does an impressive job of amassing facts or arguments” in favour of a cause as investigative journalism: “Such journalism may involve impressive research and journalist techniques, but will often lack that necessary detachment that real investigative journalism involves” (Waterford, 2002, p. 38).

Nevertheless, many eschew the notion of objective journalism and believe the mainstream media is frequently failing in its social responsibility role in a democratic society—the work of holding the centres of power to account. According to Robert Jensen, Znet columnist and academic author critiquing media independence:

This advocacy/activist tag is often applied to journalists who don’t accept the conventional wisdom of the powerful and dare to challenge the more basic frameworks within which news is reported. The idea seems to be that anyone who doesn’t fall in line with the worldview of the powerful people and institutions in society is not “objective”, and there must be motivated not by a principled search for truth but some pre-determined political agenda. (Jensen, 2007, p. 1)

Jensen contrasts the styles of two global journalists as examples. Freelance journalist John Pilger (Australian-born, living in Britain) is presented as an exemplar of advocacy journalism, while New York Times reporter John Burns represents objective journalism. Both have reported for global media on Iraq. Both describe themselves as independent journalists and reject affiliations with any political groups.

Pilger is, however, openly critical of US and UK policies towards Iraq, including unambiguous denunciations of the self-interested motivations and criminal consequences of state policies. His reporting leads him not only to describe these policies but to offer an analysis that directly challenges the framework of the powerful. Burns, in contrast … tends to accept the framework of the powers promoting these policies, and his criticism tends to question their strategy and tactics, not their basic motivations. (Jensen, p. 3)

Another example of advocacy journalism is CNN’s passionate news anchor Anderson Cooper. Deborah White (2007) describes him as embodying a “new style of advocacy journalism”: “His electrifying coverage of post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans lifted him to national prominence” in the US. In a New Zealand television context, TV3’s John Campbell represents a particular brand of advocacy journalism. He espouses views nightly on Campbell Live.

Advocacy and social issue advertising

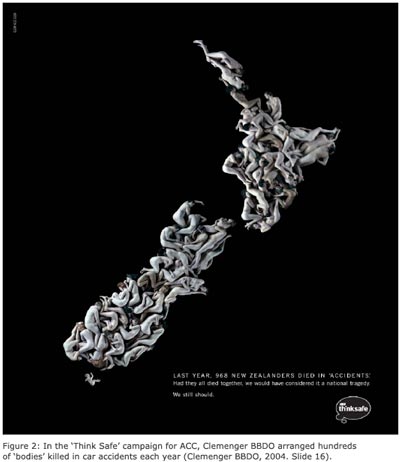

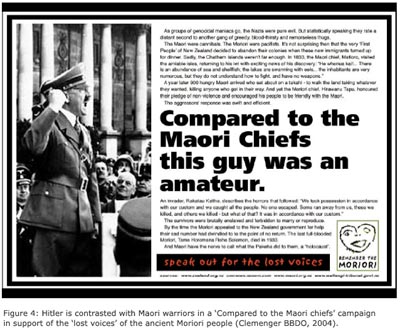

If admakers are the “quintessential commercial advocates” (Jackall & Hirota, p. 120),

social marketers are advocates for social change. Clemenger BBDO, a transnational advertising agency with its New Zealand

head office in Wellington, specialises in social issues marketing with LTSA and

ALAC as two of its major social issues marketing clients. Clemenger BBDO (2007)

suggests that the key differences between commercial and social issues marketing lie

in the outcomes. In the commercial sector, brand connection, preference and sales are

the desired result. In social issues, the emphasis is on information, attitude and

behaviour change. While the advertising campaign in the commercial sector is

measured by sales, in the public sector measurement is through behaviour change

(Figures 1, 2, 3 & 4). This is a significant difference and influences the development

of the advertising work from the brief through to the final production of the campaign.

Auckland University of Technology’s ad creativity paper is produced out of the only campus course in New Zealand that trains prospective copywriters and art directors for entry into the advertising world using “live” clients and briefs through much of the programme. Its “real world” focus parallels that of the journalism programmes—the ad creativity students are in a “creative department” producing ads for publication (electronic and print) and the news production journalism students are producing and publishing a newspaper.

Through the one-year course, the ad creativity students are exposed to non profit, commercial and social issue/marketing briefs. In every case their objective is to create work that will engage and compel in a distinctive and relevant manner. This may translate into any medium—from new media through to print, radio or television. In 2007, for example, students worked on a competitive brief for LTSA as part of an NZ Post Student Marketer of the Year initiative. Sonya Crosby of NZ Post reported that several of the campaigns, judged by industry specialists including the LTSA agency Clemenger BBDO, were being tested with consumer groups and might ultimately be produced and run.

Through an enduring partnership with ACP’s Cleo magazine, AUT Ad Creativity students were set a live “Smokefree” campaign brief, with the goal of one of the selected ads to be run as a full page in Cleo. Amie Millar of Smokefree announced in November 2007 that the anti-industry campaign developed by one of the student teams will run in its entirety—three full page ads, two of which will be funded by Smokefree.

The above advertising images are not shocking or controversial for the sake of impact alone. They are supported by facts and data that are also powerful, but in order to communicate the message in a dynamic way, arresting and engaging images are used. The campaign ads “speak to the mind, the senses or the heart. With these three registers, we cover all the ways to talk to a human being through advertising” (Dru, 1996, p. 31).

Community issue with national impact

Hunua is a small village with barely more than 3590 people (Department of Statistics,

2006) on the southern side of Clevedon, about a 40-minute drive down the southern motorway from Auckland. Its community comprises farmers, families and a growing

number of lifestyle block residents who have chosen a rural life over an urban

existence. At the 2001 Census, the unemployment rate was 2.8 percent and legislators,

administrators and managers accounted for almost a fifth (17.9 percent) of the

population.

People are drawn to the Hunua area for its walks, tramps, mountain biking, camping and fishing. The YMCA’s Camp Adair retreat has been home to many Auckland youngsters over their school and summer holidays. The Hunua Falls attracts people for its natural beauty and interesting walks through native trees and the waterfall area is enjoyed by both tourists and locals. The 14,000ha of forest that comprise the Hunua Ranges filter 2300mm of rain each year into four catchment dams providing Auckland with 60 percent of its water supply. Apart from these statistics, Hunua would not register on the horizon for most New Zealanders.

However, in 2004 Hunua featured strongly on a strategic map prepared by Transpower in the development of a controversial 400kV proposal for deployment of 70 metre pylons from Whakamaru to Otahuhu—a 220 km long stretch. Its objective was to distribute power along its grid network to the rapidly growing city of Auckland.

Of the hundreds of homes and properties along the proposed line, Hunua village was the locality facing the most impact by a proposal that was regarded as flawed by many critics. The community established a committee to develop strategies to stop the pylons. Homeowners Against Line Trespassers (HALT) and New Era Energy (NEE), based in the Waikato, became the major community forces steering an attempt to combat the Transpower proposal. While Transpower, an SOE-funded agency, ran a well-financed information and communication campaign, HALT and NEE focused on developing communication activities with limited or negligible budgets.

Community action

The groups working to halt Transpower’s proposal put aside their personal

investments and issues—many had homes and properties that would be directly

impacted on by the lines proposal—to identify and focus on critical issues:

Health and safety: Growing concerns over international research pointing to health

risks for unborn babies and young children in the form of leukemia and other cancers,

and for adults; depression, cancer and suicide (O’Rourke, 2007; Paterson, 2006).

Environmental impact: The erection of pylons in regions visited by tourists and

impacts on land values. New Zealand’s “100 percent pure” campaign would be a

travesty with a country spiked with monstrous pylons.

Technology/technical: The proposed pylons were based on an outdated technology

that was no longer being used in other parts of the Western world. This in turn had

significant financial implications in terms of performance and efficiency.

Realistic alternatives/options: A number of practical, cost effective and more efficient

options—such as upgrading the existing lines, and undergrounding were proposed by

different interest groups. In addition, local generation closer to the city, was proposed.

Process/consultation: The impact of the proposed pylons was far-reaching and

deserved fair and open consultation with all involved parties. As the project unfolded

it seemed this would not take place.

With a limited budget, HALT gaining publicity through media releases, television coverage of a community meeting when Transpower and the Electricity Commission presented their plans at the Hunua Hall in 2005. This was supported by a diligent letter writing campaign to the local press. Talkback radio was also used in the campaign. Making use of the web environment, space under pylons, and pylons themselves, were offered for sale on TradeMe for a limited period. Community newsletters and website were produced by volunteers, and small billboards with a variety of messages targeting Transpower were funded by locals for the region and along the line. Messages included:

The end of the line starts here, Transpower

When will Transpower see the light?

While Transpower ran full page and other major display advertisements in the mainstream news media, HALT and NEE’s message exposure was limited, if not effective. It seemed that one of the issues influencing the media connecting with the message was the technical aspect of the project.

The war of jargon

Most people may go through life without ever considering the difference between AC

(alternating current) and DC (direct current), the depth of a GIT (grid investment

test), the potential power of EMFs (electro and magnetic fields), or the impact of an

NoR (Notice of Requirement). The electricity industry has its own brand of jargon

and techno speak and it takes specialist knowledge and experience to unpack it and

comprehend the intricacies. For news media seeking soundbites and simple imagery,

this proved something of a mine field. Even today, three years into the campaign, few

journalists—and politicians for that matter—seem to have grasped the technical

aspects of pylons and the wider energy issue.

For communities seeking to communicate the issues; this posed challenges as well. Among the HALT committee membership are a retired scientist, an electricity industry specialist, two engineers, a university economics lecturer and a business manager. To an outsider their meetings might well have been conducted in a foreign language as they discussed the technical aspects of the Transpower proposal. It was this group knowledge that aided them in preparing submissions that in some cases were deemed more robust than those from professional organisations within the electricity industry (Berney, 2007).

For an issue as high profile and polarising as the Transpower 400kV proposal, twoway communication was critical. Transpower assured communities along the proposed line that consultation would be part of the process. However, the process turned out to be very much one sided and when specific questions were asked in person, written, phoned or emailed, they were either ignored, deferred or were instead given an answer to a different question.

In one recorded case, a Transpower representative misrepresented the truth to the community when asked about investigating the option of the Hunua ranges as an alternative for the proposed lines.

Creative advertising student brief

As part of the creative advertising programme at AUT, students are set assignments

that include the development and preparation of a creative brief. To facilitate this,

background information is provided, supported by a lecture and tutorial on the

framework of writing a brief. The background brief for the HALT campaign included

(Berney et al, 2006):

What are we talking about?

There is no doubt that New Zealand’s electricity network needs upgrading. Auckland’s recent “blackout” was caused by Transpower failing to look after, and maintain this part of the network. Transpower has been making very tidy profits in recent years, but has not been putting those funds into preventative maintenance. Rather, it has been spending it on PR spin, ad campaigns and consultants …This is a problem needs to face and it’s a problem that the government and the rest of NZ need to confront. Decisions made now will have an impact on us for generations. We have a chance to be part of the future …

As a Hunua community member and a lecturer in advertising creativity at AUT University, Jane Berney realised a synergy in briefing students to develop a campaign for the non profit organisation and the political cause. For the students, they gained the opportunity to work on a “live brief” for a highly topical issue. For the community/cause, a substantial creative resource became available. With a negligible budget, any campaign work was welcomed by the community. The students in AUT’s creative strategy paper developed a series of strategic advertising campaign briefs and then tackled a selected number of them across various media for the campaign including viral, ambient, billboard, print, and radio (Berney, 2006). The 30 or more creative teams worked for three to four weeks on their campaigns. They were not selling a product or a service in this brief. This was “social issues marketing”. While making the decision to purchase a soft drink brand, for example, can be reasonably straightforward, raising awareness of a complex issue requires a blend of strategic and creative thinking. This was the challenge put to the ad creativity students.

A further obstacle for the communication was the well known response related to community issues; “nimby” (“not in my backyard”). Recent examples of this in Auckland were the Eastern Corridor motorway proposal, and in the sporting arena, the Eden Park stadium. Here the most vocal opponents were criticised as being involved solely to protect their own property. In both of these cases the areas were home to a high proportion of professionals who had the resources—financial and expertise—to mount combative campaigns. In the rural context, many land owners in the wellheeled community of Clevedon have been fighting a waterway development on the grounds that their community is being “sold down the river”; that the stress on infrastructure would be untenable, and the unique rural culture and community atmosphere would be eroded.

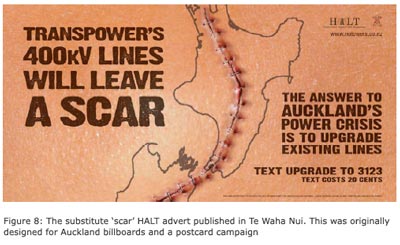

The five shortlisted “Lines” campaigns for second semester 2006 were: Tackling the health issues (poster, ashtray image and cigarette pack image); “These lines brought to you by Transpower” (pregnancy, furrowed brow and wrist images—narrowed to the wrist campaign—newspaper advertisement for Te Waha Nui) (Figure 5); the impact of pylons on New Zealand through changing road signs (signs image); “100 percent Pure” depicting the impact of the pylons on NZ’s clean green image; and a “Scar” campaign (billboard and postcard).

As with many non profit organisations, approaches were made to production and media houses to achieve cost effective exposure. The response was positive with a mobile messaging company (Altaine) donating text message support and a national billboard company (Oggi) providing a special reduced rate on Auckland billboards. Designers from a leading production house (Mark Paisey and Tom Vanderloos) provided their expertise pro bono and negotiated with a printer to produce 100,000 full colour postcards at no charge. In addition, an Auckland recording studio (Auckland Audio) provided their technicians and studios for the radio and viral work that was selected to be produced.

Through networks, both Auckland University student magazine Craccum and the AUT journalism programme training newspaper Te Waha Nui, were approached to run the campaign ads pro bono. With a three-year-old partnership already in place between Te Waha Nui (published as part of the news production paper) and the advertising creativity programme—both part of the university’s School of Communication Studies—it had been an established arrangement to showcase student advertising work in the newspaper along with the editorial content. It had been the norm on the newspaper for the teaching staff to make “management” decisions on the advertising.

The ‘Lines’ campaign

A form of disruption was used in the development of the “Lines” campaign.

Dru (1996) defines disruption as removing limits and

about finding the strategic idea that breaks and overturns a convention in the marketplace, and then makes it possible to reach a new vision or give new substance to an existing vision. (p. 55)

This approach was the creative platform for most of the shortlisted campaigns presented to the “client” and the HALT committee discussed the different approaches, settling on the campaign called “Lines”. The slogan, “These lines are brought to you by Transpower”, plays off the 400kV “Lines” that Transpower propose erecting across New Zealand, and the different “lines” that result from this; from suicide to child health and stress issues. Three ads in all made up the campaign; selected by the AUT ad creativity lecturers and the HALT committee as the campaign of choice to produce and run. The news production paper leader David Robie, who had responsiblity for advertising in Te Waha Nui, also supported the choice of advertisement. The second lecturer on the paper was opposed.

A minimum of three ads are traditionally deemed to make up a campaign in advertising. The message of the “Lines” campaign was focused on three of the potential outcomes of the proposed 400kV lines going through. Selection of one of the ads was decided on using the “cut through and impact” criteria. If only one ad could be placed in one of the media, which one would it be? There was consensus between AUT ad creativity lecturers Paul White, Dave Brown and Jane Berney, along with the HALT chairman Steve Hunt, that in terms of impact, the “wrist” ad should be selected (Figure 6).

“We’ve been impressed and energised by the individuals and companies in Auckland who’ve come to the party to produce this campaign which really impacts all of New Zealand,” said Hunt. “Our message is simple; we know Auckland needs power, and upgrading the existing lines will see the benefits coming on line, along with a saving of $400 million compared with the Transpower proposal” (HALT, 2007). Bex Radford, writer for the partnership that created the campaign, now works at one of the world’s leading creative ad agencies; Saatchi and Saatchi in Auckland. She explained the rationale behind the advertisement:

The Lines concept was created because we dug out a nugget of research about people living near pylons being more likely to commit suicide. That seemed a pretty glaring reason not to make New Zealand’s towers even bigger, and also a really compelling way in for an ad.

We felt it was appropriate for two reasons. Firstly, we felt that if the NZ government was ignoring this research in the name of progress, then the public deserved to know about it. Secondly the shock factor of this fact was guaranteed to cause widespread debate, which in this case was exactly what the pylons issue needed. (B. Radford, personal communication, September 27, 2007)

Among many recent medical reports about health risks linked to the pylons electromagnetic fields, was a submission in 2006 to the Stirling Council, Scotland, about the impact in relation to the Beauly to Denny power line, which cited 12 epidiological studies that “show increased risk of depression and suicide from magnetic fields”. Six of those concerned residential exposure to high voltage power lines (Paterson, 2006, p. 1). Professor Dennis Henshaw of Bristol University’s H. H. Wills Physics Laboratory estimated that as “many as 9000 cases of depression and 60 suicides” may be attributable to exposure to power line EMPs annually in Britain (Henshaw, 1999). A study in Finland looked at depression in 1200 same sex twins. This found that a serious risk of severe depression was nearly five times greater for those living within 100 metres of a high voltage power line than those living more than 500 metres away (Paterson, p. 1). Hunua Village already has pylons positioned too close to its community. On 4 May 2005, a community member wrote to the editor of The New Zealand Herald:

I live in the Hunua Village and our residents have health issues regarding Transpower’s existing 220kva transmission lines. Within a 500m length along Lockwood Road and the corner of Cowan Road we have had:

3 suicides

1 brain aneurysm

1 brain tumour

Serious illness

1 brain aneurysm survived but still suffering effects

2 suffering serious depression.

I am advising you that the above residents have all been 50-100 metres from the 220kva lines. (D. Levesque, personal communication, 20 September 2007)

Since 2005, a teenager has committed suicide and a man has died of cancer in the small community of Hunua. They were from different families, but both their homes were close to the Hunua Garage which has a pylon situated opposite it. Before a board of inquiry public hearing in Hamilton in August 2007, a medical expert gave testimony that living underneath pylons has been linked to cancer and other illnesses. Auckland urologist Dr Robin Smart presented documented global evidence about ill health effects from exposure to electro-magnetic fields (EMFs). Living near highvoltage lines increased the risk of childhood leukaemia, miscarriages and other ill health. However, the Ministry of Health and Transpower are comfortable with existing standards and are pushing for ‘no change’ to government policy.

On the back of 83 epidemiological studies, [Dr Smart] appealed for a tightening of current regulations by a factor of 300. A 1997 New Zealand study by Ivan Beale of Auckland University was also quoted, in which 540 Aucklanders living in homes near high voltage lines were studied against a control group. Exposure to magnetic fields ranged from 0.67 microtesla to 19 microtesla. There were significant differences between the groups in two of ten parameters, relating to memory and self esteem or depression. Women, in particular, had five times the expected rate of poor self-esteem and depression, thought to be due to the longer time they spent in homes compared to men … Another Auckland doctor, Laura Bennett, also presented her submission yesterday. A fetal and neonatal physiologist with a doctorate in paediatric medicine, [she] came to yesterday’s meeting as a resident of Clevedon … ‘The precautionary approach says we design these lines to take account of present and future health risks, including those where the science is still being investigated, at whatever cost is appropriate to mitigate these risks’. (O’Rourke, 2007)

The Te Waha Nui response

Four days before publication day of the edition of Te Waha Nui, 26 September 2006,

students on the editorial production team in the news production paper objected to a

rough proof of the HALT advertisement. Most were not happy that a graphic suicide

image was part of the advertisement and they questioned the research justifying the

theme “these lines brought to you by Transpower”. Also, a lecturer was not happy

with the advertisement. However, neither news production paper leader David Robie

nor advertising creativity paper leader Jane Berney had been present at the discussion.

Robie considered the integrity of the newspaper process had been compromised and

sought a meeting the next day between the journalism students, Berney and the two

students who had created the advert to discuss the HALT campaign project. As the

journalism students are not normally taught about creative advertising theory or ethics

(apart from a one hour guest tutorial in news production), it was important for the

students to have a better understanding of the context and process involved in

preparing the “advocacy ad” in a social issues campaign. Radford explained her

team’s research evaluations that appeared to have linked EMFs with suicide as well as

other health problems such as leukaemia, other cancers. Lou Gehrig’s disease and

miscarriages were especially disturbing (see Robie, 2006c, p. 2):

Why suicide? Knowing nothing about pylons, we decided to do some research before we started work on this brief. The studies coming out from England, Scotland and America about the health effects of pylons was overwhelming, and in the light of this it seemed hideously irresponsible of Transpower to propose bigger versions of an obviously outdated and dangerous technology as the answer to our electricity problem. Depression, miscarriage and stress were the three health effects we chose to focus on, mainly because of their potential to destroy lives—the people directly affected, their families and the communities they live in. This is defiantly an emotional and “in your face” campaign, but to be honest we felt the issue deserved nothing less than that.

Advertising lecturer Berney added:

This ad is grounded in fact and reflects the very real position of people in communities being pressured by Transpower over their homes and land in a flawed, inefficient and expensive proposal. In the other two campaign ads, the “lines” are represented by a furrowed brow (showing the concern of many New Zealanders), and stretch lines on a pregnant tummy (to highlight some of the health issues for very young children around pylons). (Ibid, p. 2)

As time was running out for a final newspaper decision—just two days left until press time—Robie wrote a “publisher’s notice”. This explained the context of the advert as a student project on a social issue, partly as a challenge to the journalism students to justify why the advert should not be run, and partly as an explanatory message if the newspaper did publish the advert. The lecturer was concerned that if journalism students—without training in advertising codes of practice or ethics—made a decision excluding an advertisement that had already gone through a rigorous class project process and had been endorsed by the three advertising lecturers, this outcome would be tantamount to censorship.

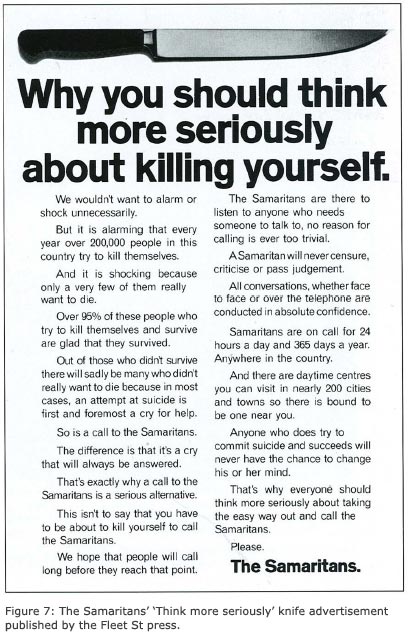

A final discussion was held the following day with the advertising curriculum leader, who spoke about advocacy advertising and social issues campaigning as a context. He also raised examples such as a controversial Samaritans advertisement (Figure 7) that ran in Fleet St newspapers depicting a knife and the provocative slogan, “Why you should think more seriously about killing yourself” (Branded for life, 2002).

He also spoke about advertising standards. Many of the students saw the advert as equivalent to a newspaper article and pointed to journalistic codes of ethics that discouraged representations of suicide and concerns about “copycat suicide”. Others were concerned about possible public reaction. Some wanted to follow up with their own journalism research on the pylons issue but nothing of substance was done. Student editor Mathew Grocott devoted the editorial theme for that edition of Te Waha Nui to the advertisement dilemma and the learning experience for the team. Writing under the title “halting ads and pylons”, he acknowledged that editorial teams did not usually have a say over the contents of adverts in their paper—but “we are not any other newspaper”. Grocott added there was no doubt that the ad was a “brilliant creation” and this was enhanced by it being produced by two AUT advertising students.

However, the ad in question featured a graphic suicide photo, a touchy subject among the media and wider community. The arguments both for and against were well considered and the debate caused much consternation and sleepless nights for our team. However, we came down on the side of caution in the end. So instead we are running an advert supporting the same campaign but created by a different pair of students. (Grocott, 2006)

The controversy had been resolved—at least for the moment—by the “Scars” billboard advert published on page 23 of Te Waha Nui (Figures 8 & 9).

‘Copycat’ suicides and media ethical guidelines

In 1999, the Ministry of Health produced a report, Suicide and the Media, which

analysed published studies and concluded that a large body of research showed a “link

between media coverage of suicide and a subsequent increase in suicides and suicide

attempts” (p. 1). Noting that New Zealand in 1995 had the highest rate of suicide in

the 15-24 year age group of selected OECD countries (p. 19), the report said the

increased risk of suicide had been shown across all age groups, but young people

struggling with serious personal, interpersonal or family problems “may be the most

vulnerable”.

In most cases it appears the person may have been influenced by either the suicide of someone else or the depiction of suicide, factual or fictional. This is referred to as copycat suicide or suicide contagion and has been linked to books, movies, television dramas, documentaries, magazines and news coverage of suicide. This phenomenon is usually due to the power of suggestion and normalisation presented in these media representations [authors’ emphasis]. (p. 1).

However, the Press Council has “anguished over the question of reporting suicides on a number of occasions” (A. Samson, personal communication, 27 November 2007), while acknowledging that evidence to support copycat deaths is “very unclear”. The council added in its 33rd annual report that it did not agree with conclusions drawn by the Ministry in its Suicide and the Media booklet (NZ Press Council Annual Report, 2005, p. 22).

Among those who watch with some trepidation the expansion of media interest in suicide are a number of mental health professionals who continue to express their fear that such media interest will trigger a “copycat” effect. Yet we stress that New Zealand’s restrictive reporting regimes, set alongside the rise in suicides in recent years, would suggest the opposite and even the strategy of “censorship” has been unsuccessful. (p. 23)

In the same council report, a detailed section headed “Suicide and the media” (pp. 24-27) critiques the Ministry report and its interpretation of the research literature, noting that “blaming the messenger as the direct cause … runs counter to the professional health view that suicide has many causes. Nor can it be certain what the trigger is in any given case”. The council’s advice to editors has been that they “need to continue to exercise the utmost responsibility to readers while exercising the freedom of the press more fully than in the past”. Reports should be, believes the council, “tempered by awareness of the language used [and] the way articles are displayed and treated” with information provided about where help can be found (p. 23).

The Australian Press Council’s Suicide Reporting Guidelines (2001) are also cautious about “inconclusive” research findings that are largely based on experience in other countries. More comprehensive body of literature in Australia is based around the ResponseAbility project from the Hunter Institute for Mental Health, which offers resources both for journalists and editors. While calling for restraint when reporting about suicides, the APC guidelines note:

Some researchers claim that an association exists between media portrayal of suicide and actual suicide, and that in some cases the link is causal. Others, on the other hand, suggest that increased reporting of suicide can act as a deterrent to people at risk, and can draw attention to the social problems that may lead to the contemplation of suicide (p. 1).

A short essay in the New Zealand Medical Journal summarising the country’s “significant contribution to the world literature on suicide behaviour” has critiqued media views of the research: “Suicide is an issue that arouses strong views, opinions and emotions—and the recent responses of some sections of the media reflect the conflicts that will inevitably arise when strongly held opinions are challenged by wellcollected evidence” (Mulder, 2007). The author, Roger Mulder, is a member of the Suicide Research Network and head of the Department of Psychological Medicine where the Canterbury Suicide Project is located. The Dominion Post (Breaking the silence, 12 February 2007; Media can help fight this scourge, 27 November 2007) and Section 14, a website devoted to free speech on social issues, are among many media voices arguing against press censorship about suicide. They have declared that no research has shown that a “society-wide taboo on discussing suicide is of any use” in reducing New Zealand’s 500-plus suicides a year.

New Zealand’s Advertising Standards Authority Code of Ethics does not include any specific guideline related to suicide, but Rule 11 on Advocacy Advertising states:

Expression of opinion in advocacy advertising is an essential and desirable part of the functioning of a democratic society. Therefore such opinions may be robust. However, opinion should be clearly distinguishable from factual information. The identity of an advertiser in matters of public interest or political issue should be clear. (1996, p. 2)

Clearly the HALT advertisement met this standard. Other standards that might arguably be invoked by critics of the advertisement are Rules 2. Truthful Presentation; 3. Research, tests and Surveys; and 5. Offensiveness.

The HALT campaign aftermath

The dilemma involved over deciding whether to publish the wrist “Lines” ad was later

addressed by Te Waha Nui editorial team member Helen Twose (2006) who delivered

a presentation about the issue at a Journalism Education Association of New Zealand

conference in Auckland in December 2006. However, the presentation barely tackled

the advocacy and social justice advertising debate to balance the issue. Nor did it

canvas the views of the advertising students or academic staff. This was a social

issues advertisement, after all, not editorial.

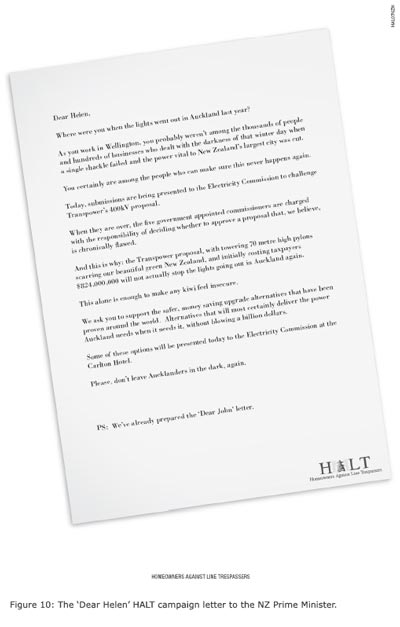

In 2007, a one-off newspaper advertisement was produced to run when the electricity Commission met to hear submissions both for and against the Transpower proposal. The “Dear Helen” ad—addressed to the New Zealand prime minister—used an emotional, yet direct approach to address the issues and a preferred solution (Figure 10). The ad appeared in both the New Zealand Herald and National Business Review during the hearings week. In 2008, another Hunua community member who lived under a village pylon died of cancer, and another local has been diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumour. In March, a Judicial Review was established to review the Transpower proposal. The finding is expected to be announced later this year.

Conclusion

The objective of the “Lines” advertising creativity campaign was to raise awareness

of the power proposal and to provoke readers to think. Ultimately a shift in public

attitudes was desired. It was not expected that the “Lines” ad would polarise AUT

journalism students to such an extent that they would decide against running the ad.

The “client” (HALT), while disappointed over the Te Waha Nui outcome, was

committed to running a campaign. With the remaining shortlisted student campaigns

being of a similar caliber in terms of their ability to disrupt and provoke, the

committee focused on the positive aspect of having another option that could run at

short notice. In the real world, this is rarely the case, and if another concept was

available, significant costs would be in producing the second campaign. The HALT

advertisement controversy raised a number of issues and questions:

- The propriety of journalists “crossing the line”: Should student editors move out of their customary editorial role into censoring a creation of advertising communication?

- “Pro bono” v paid advertising: Te Waha Nui does not usually carry regular paid advertising as do many other journalism student publications. However, in a normative commercial environment the advertisement content and message is at the discretion of the client, provided the ad does not breach any legal codes. It is not usually a decision made arbitrarily by an editor or journalists.

- Journalism guidelines v advocacy advertising: Was it appropriate to apply journalism “reporting” guidelines to advocacy advertising or social issue marketing where the creators had made a considered campaign plan based on research and course advertising guidelines supervised by staff?

- Ethical dilemmas: The journalism students mostly adopted a “taboo” frame around suicide and the purported relationship between media coverage and copycat deaths. They privileged ethical interpretations that supported that stance. Little examination was made of contesting media critiques of this frame. In other words, little effort was made to get “both sides of the story”.

In the case of many other journalism training newspapers, publication is funded by advertising where either journalism students or advertising students participate. For journalism students on newspapers such as Te Waha Nui, where publication is totally funded by a university or other institution, the students are cushioned from “real world” decision making. Stronger pedagogy exploring the relationships between advocacy journalism and advocacy advertising, or social issues marketing, would be beneficial. So would provision for closer learning partnerships between journalism and advertising students.

Ultimately, the interpretation of the message is up to the public. As Clemenger BBDO (2007) commented on social issues marketing: “Advertising alone can’t make people do anything … all we can ever do is persuade people to think about the issue, evaluate their options and take away the barriers.”

Glossary

ALAC - Alcohol Advisory Council

EMF - elctro-magnetic field

HALT - Homeowners Against Line Trespassers

LTSA - Land Transport Safety Authority

NEE - New Era Energy

SOE - state-owned enterprise

References

Andreason, A. R. (1995). Marketing and social change: Changing behaviour to promote health, social

development ands the environment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Advertising Standards Authority (1996). Advertising Codes of Ethics. Retrieved on 18 November 2007, from http://www.asa.co.nz

Alcohol Advisory Council (ALAC). (2005). ‘It’s not the drinking, it’s how we’re drinking’. Retrieved 15 November 2007, from http://www.alcohol.org.nz/CampaignItsNotTheDrinking.aspx

Australian Press Council (2001). Reporting of Suicide Guidelines. Retrieved on 15 October 2007, from http://www.presscouncil.org.au/pcsite/activities/guides/gpr246_1.html

Berman, D. (2004, June 29). Advocacy journalism, the least you can do and the no confidence movement. The Independent Media Centre. Retrieved 12 November 2007, from http://publish.indymedia.org/en/2004/06/854953.shtml

Berney, C. J. (2007). Community issues with national impact. Unpublished paper. Auckland: School of Communication Studies, AUT University.

Berney, C. J. (2006, October 2). Creative students generate campaigns with cut through. Admedia.

Berney, C. J., S. Hunt and P. White (2006). Background to the HALT campaign brief. AUT University, September.

Boyd-Bell, S. (2008). Experential learning in journalism education—A New Zealand case study. Unpublished Master of Education thesis. Auckland: AUT University.

Branded for life: Samaritans’ new image to reflect its wide-ranging role. (2002, October 2). GuardianUnlimited. Retrieved on 27 November 2007, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2002/oct/02/advertising.marketingandpr

Breaking the silence on suicide (2007, February 12). Editorial. Dominion Post. retrieved on 27 November 2007, from: http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominionpost/3956576a648.html See also: Breaking the silence on suicide (2007, February 12). Commentary. Section 14 website. Retrieved on 27 November 2007, from http://www.freespeech.org.nz/section14/category/suicide/

Careless, S. (2000, May). Advocacy journalism. The Interim. Retrieved 12 November 2007, from http://www.theinterim.com/2000/may/10advocacy.html

Clemenger BBDO (2007). Social marketing [Powerpoint presentation]. Clemenger BBDO (2004). Selling vs social [Powerpoint presentation].

Department of Statistics (2006). Census profile. Retrieved on 13 November 2007, from http://www.stats.govt.nz/NR/rdonlyres/A2262863-B2F5-4710-BD1B878E45782EE9/0/FranklinDistrict.xls

Dru, J. M. (1996). Disruption: Overturning conventions and shaking up the marketplace. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Fram, E., S. P. Sethi, and N. Namiki (1993, July n.d.). Newspaper advocacy advertising: molder of public opinion? USA Today. Retrieved on 11 November 2007, from findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1272/is_n2578_v122/ai_13196301

Grocott, M. (2006). Editorial: Halting ads and pylons. Te Waha Nui, September 29, p. 19.

Hastings, G. (2007). Social marketing: Why should the devil have all the best tunes? Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Henshall, D. L. (2006). Health effects of EMFs—evidence and mechanisms. Bristol: H. H. Wills Physics Laboratory, University of Bristol. Retrieved 28 October 2007, from http://www.electricfields. bris.ac.uk/health.html

Homeowners Against Line Trespassers (HALT) (2006, October 2). Auckland creatives and companies campaign against Transpower’s 400kV proposal [Media release]. Auckland.

Hunter Institute for Mental Health. (2008). ResponseAbility mental health resources for tertiary education. Retrieved on 10 February 2008, from http://www.responseability.org/site/index.cfm

Jackall, R., and J. M. Hirota (2003). Image makers: advertising, public relations and the ethos of advocacy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jensen, R. (2007). Beyond advocacy v objective journalism: who is really objective? Znet. July 28. Retrieved on 11 November 2007, from http://www.zmag.org/content/showarticle.cfm?ItemID=13390

Johnson, P. (2007, n.d.). More reporters embrace an advocacy role. USA Today. Retrieved on 13 November 2007, from http://www.usatoday.com/life/television/news/2007-03-05-social-journalism_N.htm

Kotler, P., and Zaltman, G. (1971). Social marketing: An approach to planned social change. Journal of Marketing, 35, 3-12.

Levesque, D. (2007). Personal email communication to co-author C. J. Berney, September 20.

McChesney, R. W., and J. Nichols (2002). Our media, not theirs: The democratic struggle against corporate media. New York: Seven Stories Press.

McGregor, J. and M. Comrie (Eds) (2002). What’s news? Reclaiming journalism in New Zealand. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Media can help fight this scourge (2007). Editorial: The Dominion Post. Retrieved on 27 November 2007, from http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominionpost/4288778a6483.html

Ministry of Health (2006) Suicide and the media—the reporting and portrayal of suicide in the media. Retrieved on 18 November 2007, from http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/0/A72DCD5037CFE4C3CC256BB5000341E9/$File/suicideandthemedia.pdf

Mulder, R. (2007). Suicide prevention in New Zealand. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 120(1251). Retrieved on 27 November 2007, from http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/120-1251/2463/

NZ Press Council (2004). Statement of Principles. Retrieved on 15 July 2007, from http://www.presscouncil.org.nz/principles.html

NZ Press Council (2005). 33rd annual report. Wellington. Retrieved on 15 July 2007, from http://www.presscouncil.org.nz/articles/NZ Press Council AR 2005.pdf

O’Rourke, S. (2007, August 21). Pylons major health hazard, inquiry told. The New Zealand Herald.

Paterson, I. (2006). Health impacts of the proposed Beauly to Denny power line. Presentation to Stirling Council, October 17. Retrieved on 28 October 2007, from http://www.cairngormsagainstpylons.org/pdf/health_risks.pdf

Protess, D. and F. Cook, J. Doppelt, J. Ettema, M. Gordon, D. Leff, and P. Miller (1991). The journalism of outrage: Investigative reporting and agenda building in America. New York: Guilford Press.

Radford, B. (2007). Personal email communication to co-author J. Berney, September 27.

Robie, D. (2006a). NP_diary_2006.

Robie, D. (2006b). An Independent Student Press: Three Case Studies from Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Aotearoa/New Zealand. Asia Pacific Media Educator (17): 21-40.

Robie, D. (2006c). Why we’re publishing this graphic advert. [Draft publisher’s letter]. September 27.

Robie, D. (2004). Mekim Nius: South Pacific media, politics and education. Suva: University of the South Pacific.

Robie, D. (1995). Uni Tavur: The evolution of a student press. Australian Journalism Review. 17(2): 95-101.

Samson, A. (2007). Personal email communication to co-author D. Robie, November 27.

Siegel, M. & Lotenberg, L. (2007). Marketing public health. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Solomon, N. (2006, May 16). Corporate media and advocacy journalism. Media Beat. Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR). Retrieved 13 November 2007, from http://www.fair.org/index.php?page=2885

The New Zealand Herald (2005, May 4). Letter to the editor.

Twose, H. (2006). To publish or not to publish: A student’s ethical dilemma [Powerpoint presentation]. Paper presented at the Journalism Education Association (JEA) /Journalism Education Association of New Zealand (JEANZ), Auckland, December 4-6.

Waterford, J. (2002). The editor’s position. In Tanner, S. (Ed.). Journalism: investigation and research (p. 37-47). Sydney; Australia: Longman.

White, D. (2007, n.d.) Profile of Anderson Cooper, journalist and CNN anchor. About.com Retrieved 13 November 2007, from http://usliberals.about.com/od/peopleinthenews/p/AndersonCooper.htm

About the Authors

Jane Berney has been working in the field of creative communication for more than three decades with a special interest in the non-profit sector. She is a part-time advertising creativity lecturer with AUT University’s School of Communication Studies and manages her Hunua community’s campaign against Transpower’s 400kV line proposal. jane.berney@aut.ac.nz

Dr David Robie is Associate Professor and Pacific Media Centre Director with AUT University’s School of Communication Studies. He has been publishing coordinator for several student journalism newspapers, including Uni Tavur (UPNG), Wansolwara (USP) and Te Waha Nui (AUT). david.robie@aut.ac.nz

An earlier version of this article was presented at the Journalism Education Association of New Zealand conference at Massey University, Wellington, 10-11 December 2007.