Handsome devils: Mobile imaginings of youth culture

Handsome devils: Mobile imaginings of youth culture

— Centre for Social Research in Journalism and Communication, University of New South Wales

and — Centre for Social Research in Journalism and Communication, University of New South Wales

Abstract:

Mobile technologies are becoming central to contemporary media — yet there has been little critical examination of mobiles, or of their role in community, alternative, and citizens’ media. Accordingly, in this paper we examine the way that mass media representations of mobile media are bound up with individualistic interpretations of youth culture. Advertising campaigns herald a new era of youthful mobile media interactions, from glamorous 20-somethings silhouetted with their iPods to teenagers sending flirtatious text messages. At the other end of the spectrum, familiar youth panics are being translated into technological iterations, continuing “the unhappy marriage of youth and media theory” (Ishita, 1998). We argue such narratives form a larger picture of what we call ‘seductive and destructive’ mobile imaginaries. Youth culture is often a site upon which broader social concerns are projected, and the current mobile imaginaries reveal the affective patterns of anxiety and desire that mark popular representations of youth and technology. A critical understanding of such imaginaries helps locate the ‘our’ in mobile media, and so articulate sustainable media and cultural futures.

Introduction

Mobiles are central to contemporary media. Witness the ubiquity of mobile phones in both the developed and developing world, the phenomenon of text messaging, and its role in mainstream television interactivity, and the rise of camera and video phones. Then there are the new developments associated with video, film, and television for mobiles, not to mention mobile Internet, games, and forms of locative media using mobile and wireless technologies (Goggin & Hjorth, 2006). While there has been considerable interest in the possibilities of mobiles for participatory, community, citizen and alternative media (for instance, Hankwitz, 2007; Rheingold, 2002; Schneider, 2007), we argue that mobiles are still not well understood or integrated into such conceptions.

While being associated with privatisation and deregulation of telecommunications, mobiles are also seen as reconfiguring the personal. The mobile phone is most commonly thought about in Australia and in many other societies, as associated with one particular person — as an intimate, individual media technology. But it also shifts boundaries of the personal and the public. As Morley argues, the mobile phone dramatically illustrates how people in public spaces conduct private conversations, at once present and not fully there (Morley, 2000, p. 97). The individualism of mobiles is further complicated by their capacity for powerful forms of interconnection. The computing, networking, and imaging power in mobile handsets has been accompanied by new cultural representations and practices that we are still comprehending — and, we would suggest, still trying to theorise as our media, in the sense of a collective, shared technology.

Our focus in this paper is on understanding the discourses that surround mobiles and youth culture. As our opening paragraphs suggest, by mobiles we mean ‘mobile phones’. With the term ‘mobile media’, we wish to extend the range of reference to signify emerging media technology, some but not all of which are based on cellular mobile networks (especially third-generation networks). For instance, we are interested in thinking about forms of mobile media that build upon earlier forms of portable media — for instance, the handheld transistor radio, the 1980s icon of the ‘beatbox’, the portable television set, and famously the Sony Walkman (see Du Gay et al., 1996). Some would describe the newspaper a form of portable media. For the purposes of this paper we are interested in the crossovers between cellular mobile network-based-media and audio/visual personal media, with a focus on technologies building upon the mobile phone and also Apple’s highly popular iPod.

Rather than focus upon obviously ‘independent’ or ‘community’ or ‘activist’ uses or concepts of mobiles, we are interested in the broader social imaginaries operating around youth and mobile media. We think this is important, ground-clearing work to undertake, as a contribution to understanding what our (mobile) media might mean. In doing so we take inspiration from the important Japanese collection Personal, Portable, Pedestrian: Mobile Phones in Japanese Life — in which the analysis of myths, discourses, and imaginaries of the keitai (networked and game-enabled phones) is key to locating the mobile in that society’s mediascape (Ito, Okabe, & Matsuda, 2005; Matsuda, 2005; Okada, 2005; Kato, 2005). This Japanese contribution is perhaps the most significant and suggestive to date, though there has been other important work on how mobiles are imagined. Here we would note studies using a variety of approaches, including social representations (Contarello, Fortunati, & Sarrica, 2007), cultural scripts (Shade, 2007), different kinds of discourse and textual analysis (Aguado & Martínez, 2007; Caron & Caronia, 2007), and social shaping and domestication work (Scifo, 2005).

Our interest in social imaginaries of youth and mobile media comes from previous work we have respectively undertaken. Crawford has theorised discourses and imaginaries on youth and generation in her 2006 book Adult Themes, and Goggin has looked at the cultural and discursive shaping of mobiles in his 2006 Cell Phone Culture. As part of this work, both of us have been interested in moral panics. Moral panics are well established in social and cultural theory since the 1970s as a phenomenon in which social control and relationships of power are secured and maintained by the creation of folk-devils (Cohen, 1972; Hall et al., 1978). There has been considerable debate about the nature of moral panics, particularly in the context of the rapid social changes over the last decade and the emergence of new theoretical frameworks, such as the emphasis on ‘risk’ (Critcher, 2003; Thompson, 1998; for a wide survey and light relief, see Kroker, Kroker & Cook, 1989). Nevertheless, moral panics persist, and young people, new technologies, and new tastes commonly feature as objects of such panics. Particular panic formations not only recur but also enjoy long lifespans, as the case of television reveals (for a recent inventory and critique of television panics, see Lumby & Fine, 2006).

For their part, mobiles have occasioned many new panics (Goggin, 2006). Examples abound, but while presenting an earlier version of this paper in April 2007, we did so just as news was breaking of a terrible Sydney case where a mobile phone was used to video a rape (Braithwaite & Cubby, 2007). This was a case in which the mobile became an index of more profound and distressing issues in contemporary society, yet it was emerging technology that became the focus of concern in the mainstream media, rather than the violent attack itself.

One important approach to youth and media, including mobiles, that helps to put moral panics in perspective is the study of actual use and consumption, and their accompanying social meanings, functions and context (Meyrowitz, 1985; Ling, 2004). There is now a sizable literature on youth and mobiles (including Caron & Caronia, 2007; Caronia & Caron, 2004; Lorente, 2002; Wang, 2005), which can be placed in a burgeoning general literature on youth and digital technology (Sefton-Green, 1998; Loader, 2007; Montgomery, 2007; Thomas, 2007). Such studies are generating insights that put into question many of the claims that feature in mobile panics. It is a curious thing, however, that this knowledge has little significant impact on the ongoing operation and proliferation of moral panics through the mass media.

We argue that moral panics underscore the importance of taking seriously the imaginaries associated with youth and media technology, in which mobiles are an increasingly important component. Panics contribute to social understandings and stereotypes of particular kinds of users who are seen as problematic. Panics operate not only by marking out and stigmatising certain groups of users, or type of users, but also seek to inoculate other groups (or indeed, the general population) against the contagion of undesirable activities. Thus, moral panics about youth are not just about demarcating one ‘problem’ group, but establishing a site of anxiety where broader concerns about society are established and reproduced (Lesko, 2001, p.50). Beneath the unsubtle clamour that accompanies them, moral panics operate in complex ways and can contain multiple concerns.

The term ‘youth’ itself is also complex and fluid, a category which changes meaning and membership dependent on context. Many authors have written about the social and historical construction of youth (Ariés, 1962; Gillis, 1974; Hebdige, 1988), and the way in which youth connotes change as well as being “a site of both the fears and promises offered by that change” (Acland, 1995, p.26). Popular representations of youth also have direct impacts on youth policy, even when these are not substantiated by detailed studies (Irving et al., 1995). The way youth and youth culture is imagined is important, particularly as ‘threats’ or panics emerge. We are considering youth here as a contingent discourse and are observing its deployment as a category in mainstream media.

There are several contradictory themes that emerge in the popular imaginaries of young people and mobile media. The panics we will consider here are the fear of social disconnection, that young people are using mobile media to isolate themselves from the world, and hyperconnection, an excessive dependence on connection to one’s social networks. Within these debates we find paradoxes of individuality and intimacy, the complex relationships between the ‘me’ and the ‘our’, the individual and the collective, that mobile technologies are taken to embody.

Two Myths of Mobiles — Disconnection and Hyperconnection

We will begin with some images that both represent and feed what we see as the mobile imaginaries around youth culture. These images are drawn from advertising found on billboards, in magazines and newspapers in a range of Western countries. These images are embedded in different cultural and geographic locations, and together they represent different aspects of the disconnection/hyperconnection problematic.

Disconnection

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

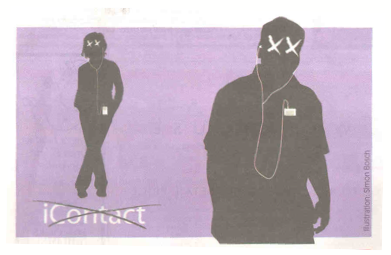

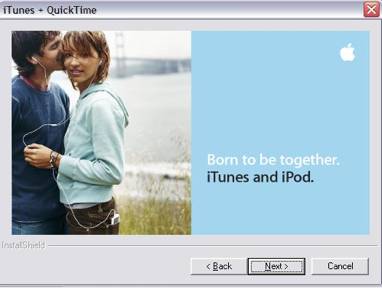

The images above are drawn from different sources. The first is an Apple billboard ad, the second is an illustration for an Australian newspaper article, the third is an in-built software ad that appears when installing Apple’s iTunes program. Nonetheless, they all draw on and contribute to the mythic imaginaries of the iPod and its place in youth culture. As Roland Barthes wrote in his discussion of advertising images, “mythical speech is made of a material which has already been worked on so as to make it suitable for communication … all the materials of myth … presuppose a signifying consciousness” (1973, p.119). Effective myths are those that draw on pre-existing, pre-digested narratives, stories that recur in a range of popular sources. But not only do these images draw on established ideas of mobile technology and its users, they also reinforce conceptions (both positive and negative) of what mobile media potentiates and who is most drawn to it.

In Figure 1, we see the classic first generation billboard advertisement for the iPod. The iPod user is surrounded by colour, earbuds inserted, in an ecstatic moment of solitary music listening. As the iPodiste is in silhouette, the user is telegraphed as ‘youth’ by the outlines of clothing (casual wear with a hipster twist) and by posture: a free-frame moment of perfectly self-assured dancing (many of the models in the series were professional dancers). Figure 2 shows us how this image has been sardonically reappropriated in an illustration that accompanied an article in the Sydney Morning Herald. Journalist Jacqueline Lunn writes about what she perceives as the growing isolation of urban life:

[It] struck me the other day when I hopped in the lift after catching a train to work … that I had not made eye contact with anyone since I left home. This city is teeming with people in their own little bubbles armed with iPods, mobiles or a vacant look that only cracks for another person when they have to order a skim soy chai latte. (Lunn, 2007)

The image reflects this view of dysfunctional public space, with a man and woman both plugged into iPods but their eyes are rendered as crosses: deaf and blind to the world around them. They represent the archetype of the socially isolated, technologically mediated modern subject. This connects with a broader public discourse on the potential harm of mobile media to human contact, as evidenced in a comment made by the chief executive of Relationships Australia in NSW, who said of the iPod: “Without exaggerating, it potentially affects our human-to-human interactions … I think they do allow you to be within your own world and think only of your interests.” (quoted in Taylor, 2006)

The anxiety here is that technologies that offer private audio and visual universes produce ‘telecocooning’, which will invariably result in a loss of community and social cohesion. As Stephen Fenech asks in the Daily Telegraph: “Are we turning into individual shells totally absorbed in the devices we’re carrying?” (Fenech, 2006) He argues that “these communication devices are contributing to breeding a society of earphone wearers who are so focused on whatever form of personal media they are listening to or watching, they are losing their communication skills.” An American article on iPods reaches a similar conclusion:

The meta-environments that iPods create … isolate people to the point where we are not just bowling alone, as Harvard Professor Robert Putnam might put it, but we’re even walking along and experiencing the world from the confines of a musical cocoon. (Pump, 2005).

Such fears about the iPod as a threat to the social are commonly focused on the young (Crawford, 2006). Youth culture becomes the site of contest between the replication of the social order (conformism) and the resistance or rejection of pre-existing norms. Thus if young people are using iPods rather than participating in established forms of social interaction, they jeopardise the concept of an idealised public space of open and spontaneous interactions. Some commentators argue that such technologies not only threaten prior forms of public space, but of the polis itself: be it work, politics or education. Peter Sheahan writes that the current generation of young people ”knows no other world than one filled with Big Brother, the internet, mobile phones, Sony PlayStation, Apple iPods and DVDs … They are disengaged from the political system, the school system, the workforce.” (Sheahan, 2005, p.63).

This view shares similarities with the media panic about SMS being used by young people as a way to avoid face-to-face human communication (see Florez, 2003). In Disconnected, Nick Barnham writes of texting shorthand: ‘”Language is one more strategy of disconnection, and youth languages are creating vast swathes of culture that are unintelligible to people who like to think of themselves as literate” (Barnham, 2004, p.209). The popularity of SMS is seen as a degradation of written expression, resulting in a widespread decrease in formal literacy levels (Goggin, 2006). Of course, in these accounts, social disconnection, on the one hand, and hyperconnectedness or addiction, on the other, are mutually imbricated; young people are seen as too fixated on their phones and media players to manage ‘real’ connections with other people, so they are at once too connected and utterly isolated.

Of course, technology companies are aware of these negative associations with mobile technologies, and they actively seek to combat them. In Figure 3 we see an Apple advertisement that seeks to establish counternarratives to emphasise the potential intimacy of the iPod as a shared technology. The image offers a glimpse of a couple in close quarters sharing an iPod: a young man leans close to his female companion, his smiling mouth close to her ear. He may be whispering or kissing while she looks directly at the viewer, her fingers grasping the headphone cable. The caption reads ‘Born to be together: iTunes and iPod’. The phrase is selling the iPod owner on the natural (indeed necessary) fit between the digital music player and the software, while underscoring the intimate physicality of sharing an iPod. This ad imagines an ideal mutual sound-world, with a deeper desire for this kind of mobile media not just to be ‘sexy’ but to be genuinely hospitable and sociable.

Hyperconnection

If one prominent element of mobile media imaginaries turns on a fear of social decay through isolation of the individual, the following images suggest a twin motif: fear of inescapable hyperconnection.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 4 is a Telstra advertisement from March 2007 promising that one can “Be connected like never before”, and depicts five people simultaneously using mobile phones. All five are conjoined by their clothes which are stretched and stitched together, leaving them manacled to each other. The image is meant to be humorous and positive (”think of all the people you can connect with!”), but has strong undertones of young people being trapped, tied and literally strung up.

The second image in this pair explicitly takes on the dystopian aspects of hyperconnected (see Figure 5). Captioned with the question ¿Tu vida es móbil? (‘Is your life mobile?’), it features a woman literally chained to her mobile phone with chains and padlocks around her neck. While the Spanish consumer association Facua is alluding to the risk of being trapped in a single phone plan, the image exemplifies the ‘electronic tethering’ discussed in the mobiles literature (Middleton, 2007).

These two images also show the continuities between the representation of young people as harbingers of potentially destructive social change and as victims who need protection. Young people are at once seen as introducing the dependency on technologies whose allure they cannot withstand, compromising established value systems, while needing to be protected from themselves: ‘freed’ from their chains. Acland describes this as the “dialectic of youth-in-trouble and troubling-youth” (Acland, 1995, p.28) a well-established double articulation that informs the hyperconnection/disconnection debates. Thus, when an article in the Herald Sun proposes that young people are driving a growing fetishisation of new technology, it is framed in the language of victims: “while the young generation is clued on the latest gadgetry, it is clueless about face-to-face interaction … its devotion to being technologically connected means it is more isolated that previous generations” (Burns, 2006).

Why, when mobile media use has become prevalent across all age groups, are ‘young people’ still defined as so visible, problematic and prone to excesses of connectedness and withdrawal? The social field of ‘youth’ is malleable in both its historical and definitional boundaries: the age range shifts, as do the behaviours deemed as problematic and the suggested remedies. Mobile scholars have focussed on in particulars of charting young people’s use of mobiles and the formation of new mobile cultures (for example, Kasesniemi, 2003). There has also been important work that seeks to identify what it is about the mobile phone, in particular, that raises such concerns over youth (see, for example, Ling, 2004 & 2007). Certainly, Castells et al. argue that youth culture and wireless technologies are seen as deeply interlinked, with a “correspondence between global youth culture, the networking of social relationships, and the connectivity potential provided by wireless communication technologies” (2007, p.169). But this does not resolve why or how this relationship operates as a key site for social anxieties.

To begin to understand these dense social imaginaries requires a recognition of their multiple sources. Firstly, the mobile has played an important role in a transformation of how reality itself is represented, as Leopoldina Fortunati has suggested:

What seems to emerge quite clearly is the role played by the mobile phone in changes not only and not so much in society, as reality in the wider sense, or better, in its social representation. The use of this instrument has in fact made a notable contribution to modifying the social conception of space and time, determinations capable of integrating, stabilizing and structuring reality (Fortunati, 2002).

Furthermore, the mobile phone is in now transition. Since the rise of text messaging and then the popularity of mobiles as an image-making and sharing device with the advent of camera phones, we see mobiles taking on a wider cultural role. This is now broadening and deepening further still, with the explicit reworking of mobiles as a facet of convergent mainstream media. Technologies such as the Blackberry and the iPhone are useful examples of this shift. The social imaginaries associated with the mobile phone are already commingling with those of email, MP3 players, the Web and instant messaging, each of which have their own cultural associations. From the Walkman to the Discman, the iPod to the iPhone, we see old media forms contained in new types of cultural and urban experiences (Bull, 2007).

Thirdly, the position of mobile media technology in mainstream culture, as it augments and enlarges its socio-technical roles, raises issues of power, citizenship, and generational change. Youth, as Nancy Lesko has argued, is the conceptual field where cultural and political contests about the nature of the social take place, and where its potential problems are diagnosed and studied (Lesko, 2001, p.50). In this sense, debates about young people become a symbolic theatre in which fears about technological change represent wider issues of communication, the development of the polity, and the production of model citizens (Crawford 2006; see also Fortunati & Strassoldo, 2006).

Understanding Mobiles as Our Media

One response to the complex imaginaries of mobile media is to dismiss these advertising campaigns and newspaper features as distortions of the intricacies of mobile media use. Certainly the research literature on mobile phones, and the embryonic work on mobile media, offers much evidence to suggest that while these technologies have become important to youth culture, they tend to provide additional options and new modes for useful social connection, rather than either disconnection or hyperconnection. A more compelling response is to observe how new ideas of the social are being devised hand-in-hand with new technologies, as actor-network-theorists have suggested (Chesher, 2007; Latour, 2005; Woolgar, 2005).

In this vein, we can go further and see what we can learn from these narratives of mobile media and youth. What is at stake here is how cultures conjure with human affects – be it fear, desire, pleasure or shame – and how these are generated by and projected onto new cultural objects of mobile technology. Thus a more nuanced reckoning is required to understand how these mobile imaginaries perform what Frederic Jameson describes (in Freudian terms), as ‘transformational work’, upon people’s anxieties, wants, and needs (Jameson, 1979; cited in Gunster 2006).

While there are many emotive themes in the discourse around mobile media use, the one we would like to consider in the context of discussions of ‘our’ media is the anxiety around increasing individualism. Amongst the transformational work being done in the images above, there is a focus on the tension between individualism and community. Portable media technologies continue to be read as the epitome of what Raymond Williams described some decades ago as ‘mobile privatization’ (Williams, 1974), and mobile phones are now often invoked as a latter-day epitome of this (for example, McGuigan, 2005 & 2006). But this literalism can often obscure the complex and surprising ways that ‘privatizing’ technologies can be put to more public, collective use and vice versa.

Anecdotal evidence that the primacy of the individual is being emphasised by mobile media use can be seen around us: the man on the bus, white headphones firmly placed in ears, or the woman walking through the city, absorbed by her mobile phone conversation and seemingly oblivious to her surrounds. But rather than signs of disconnection, studies on mobiles conducted by Ito and others indicate to the contrary. Mobile media forms can be very social, facilitating social inclusion and, in the case of the mobile phone, as a kind of “glue for cementing a space of shared intimacy.” (Ito, 2004).

While the uses of mobile phones to facilitate work and intimate relationships are well documented, they are rarely considered a tool for collective communication. This mirrors concerns raised by Wellman in studies of Internet use, where he uses the term ‘networked individualism’ to describe how a single person has become the primary unit of connectivity, not a household or a broader group (Wellman, 2001). Mobile phones and wireless computing, in their turn, have furthered the development of ‘personal communities’ where ‘the essentials of community’ are supplied separately to each individual without regard to place (Wellman et al., 2003). Rather than ‘networked individualism’, Fortunati uses the phrase ‘semi-socialised individualism’ to account for both the sociability of mobile phones and their individualising tendencies.1 But both Fortunati and Wellman agree that the idea of community is changing, becoming more flexible, multiple and partial.

Conclusion

The implications for mobile media as a tool for community and other forms of collectivities are still developing. Mobiles have already been embraced by some alternative and citizen media groups as an exciting new possibility for communication and action — an opportunity that was also recognised and seized on the Internet in the late 1990s (Meikle, 2002). Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in activist uses of mobiles (Rheingold, 2002), on the one hand, and the extensive uses of mobiles in developing countries (for instance, see Donner, 2004 & 2007; Sullivan, 2007). Despite this, it is fair to say that mobiles are still on the margins of larger-scale community media, as represented in community television and radio, or even new online initiatives. Wireless computing has loomed larger, perhaps because of its clearer association with community computing and networking movements. The mobile phone, and now mobile media, however, have tended to be rather left to the highly commodified commercial sectors, and, implicitly at least, associated with the individual.

By offering an analysis of mobile imaginaries, we seek to problematise notions of young people as a highly individualised cohort (prone to excesses of disconnection and hyperconnection) and mobile media as a socially corrosive technological form. These myths appear to be stubbornly embedded in a range of dominant cultural representations. To advance our work we will embark in 2008 on a three-year-national study of youth culture and mobile media, funded by the Australian Research Council: Young, Mobile, Networked: Mobile Media and Youth Culture in Australia. In this project we aim to make a detailed analysis of these imaginaries, based on a large corpus of texts, images, and sites that we will collection. We hope to take forward and refine the analysis of images we have offered here within a large-scale qualitative, discourse analysis with quantitative mapping of young people and mobile media consumption. Accordingly, we are deliberately quite specific in nominating and constructing our context for this large-scale project (in our case, national and local, as a route to observing configurations of global mobile media).

We hope such research will prove useful for a number of reasons, not least to delineate the precise nature of youth consumption of mobile media in Australia. While consumption is a contested term, we understand it broadly as a way of approaching the productive, rich, and also problematic relationship of users to culture and media. Certainly at this conjuncture there are considerable issues posed about the nature of the new kinds of consumption being constructed, or installed, in digital cultures and technologies (with consumers called upon, for instance, to undertake a great deal of activity in social networking technologies that can then be harvested by large commercial forces). The stakes in studying and debating consumption has been heightened also with the rise of accounts of the user-as-innovator. Mobile phone users have been received considerable attention for their everyday, do-it-yourself, user-generated content innovation (as some of the catch-cries go) (Bell, 2005; Haddon et al., 2005; Hjorth, 2005). Accounts of the implications and politics of such innovation vary, with some seeing it as providing the grounds to refresh the tried innovation systems of traditional business and industry (along the lines of von Hippel, 2005), while others claiming it has significant potential to transform existing social relations (Rheingold, 2002).

In the meantime, media commentaries and images that problematise the use of mobile technologies by young people continue unabated. As Acland has observed, this intense concern about the behaviour of youth ‘can be collapsed into a fear of the imperfect replication of the social order’ (Acland, 1999). On this line of thinking, community, communication and the polity are being reproduced in hybrid, imperfect forms. These recombinant designs continue to inspire yet more media panics and myth-making. The space for ‘our media’ is still developing in our understanding of mobile technologies. For the time being the popular media continues to represent the relationship of mobile media to youth culture in ways that are both over-glamorised and demonised. As Barthes writes in the final words of Mythologies, much of our contemporary discourse is still being ‘terrorized, blinded and fascinated’ by these handsome devils (Barthes, 1973, p. 174).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aguado, J. M., & Martínez, I. J. (2007). The construction of the mobile experience: The role of advertising campaigns in the appropriation of mobile phone technologies. Continuum, 21(2), 137-148.

Barnham, N. (2004). Disconnected: Why our kids are turning their backs on everything we thought we knew. London: Random House.

Barthes, R. (1973). Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers). London: Paladin.

Bell, G. (2005). The age of the thumb: A cultural reading of mobile technologies from Asia. In P. Glotz, S. Bertschi, & C. Locke (Eds.), Thumb culture: The meaning of mobile phones for society (pp. 67-88). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Braithwaite, D., & Cubby, B. (2007, April 5). Gang rape filmed on mobile phone. Sydney Morning Herald, p. 1.

Bull, M. (2007). Sound moves: iPod culture and urban experience. London: Routledge.

Burns, A. (2006, May 28). Youth in need of a reality check. Sunday Herald Sun, p. 39.

Caron, A., & Caronia, L. (2007) Moving cultures: Mobile communication in everyday life. Montréal: McGills-Queen’s University Press.

Caronia, L., & Caron, André H. (2004). Constructing a specific culture: Young people’s use of the mobile phone as a social performance. Convergence, 10, 2, pp. 28-61.

Castells, M., Fernãndez-Ardèvol, M., Qui, J.L., & Sey, A. (2007). Mobile communication and society: A global perspective. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chesher, C. (2007). Becoming the milky way: Mobile phones and actor networks at a U2 concert. Continuum, 21(2), 217-226.

Chow, R. (1990-91). Listening otherwise, music miniaturized: A different type of question about revolution. Discourse, 129-48.

Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics: the creation of the Mods and Rockers. London: MacGibbon and Kee.

Contarello, A., Fortunati, L., & Sarrica, M. (2007). Social thinking and the mobile phone: A study of social change with the diffusion of mobile phones, using a social representations framework. Continuum, 21(2), 149-164.

Critcher, C. (2003). Moral panics and the media. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Donner, J. (2004). Microentrepeneurs and mobiles: An exploration of the uses of mobile phones by small business owners in Rwanda. Information Technologies for International Development, 2(1), 1-21.

Donner, J. (2007). Perspectives on mobiles and PCs: Attitudinal convergence and divergence among small businesses in urban India. In G. Goggin & L. Hjorth (Eds.), Mobile Media: proceedings of an international conference on social and cultural aspects of mobile phones, convergent media and wireless technologies (pp. 253-261). Sydney: Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney.

Du Gay, Paul, et al. (1997) Doing cultural studies: The story of the Sony Walkman, London and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fenech, S. (2006, August 17). iPod users plugging into their own world. Daily Telegraph, p. 24.

Florez, M. (2003, April 27). Human touch suffers at hands of message mania. Sunday Telegraph, p. 42.

Fortunati, L. (2002). The mobile phone: Towards new categories and social relations. Information, Communication & Society, 5, 4, pp. 513-528.

Fortunati, L. & Strassoldo, R. (2006). Practices in the use of ICTs, political attitudes among youth, and the Italian media system. In P.-L. Law, L. Fortunati, & S. Yang (Eds.), New technologies in global societies (pp. 125-158). New Jersey, NJ: World Scientific.

Fortunati, L. & Yang. (2005). News circulation by means of mobile phones in China. Paper delivered at ‘Mobile Communications and Asian Modernities II: Information, Communication Tools & Social Changes in Asia’, Beijing, October 20-21. Retrieved September 6, 2007, from www.parishine.com/FTreport/mobile/ppt/LeopoldinaFortunatiAndShanhuaYang.ppt.

Gillis, G. R. (1974). Youth and History. London: Academic Press Inc.

Goggin, G. (2006). Cell phone culture: Mobile technology in everyday life. London and New York: Routledge.

Goggin, G. & Hjorth (Eds.) (2007). Mobile Media: proceedings of an international conference on social and cultural aspects of mobile phones, convergent media and wireless technologies. Sydney: Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney.

Gunster, S. (2006). Second nature: Advertising, metaphor and the production of space. Fast Capitalism, 2(1), www.fastcapitalism.com. Retrieved September 4, 2007, from http://www.uta.edu/huma/agger/fastcapitalism/2_1/gunster.html

Haddon, L., Mante, E., Sapio, B., Kommonen, K.-H., Fortunati, L., Kant, A. (Eds.). (2005). Everyday innovators: Researching the role of users in shaping ICTs. London: Springer.

Hall, S. et al. (1978) Policing the crisis: Mugging, the state, and law and order. London: Macmillan.

Hankwitz, M. (2007). Rethinking rituals: Mobile media in activist and protest culture. In G. Goggin and L. Hjorth (Eds.), Mobile Media: proceedings of an international conference on social and cultural aspects of mobile phones, media and wireless technologies (pp. 245-252). Sydney: Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney.

Hebdige D. (1988). Hiding in the Light. Comedia: London.

Hjorth, L. (2005). Postal presence: A case study of mobile customisation and gender in Melbourne. In P. Glotz, S. Bertschi, & C. Locke (Eds.), Thumb culture: The meaning of mobile phones for society (pp. 55-66). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Irving, T., Maunders, D., Sherington, G. (1995). Youth in Australia: Policy administration and politics. Macmillan: Melbourne.

Ito, M. (2004). Personal portable pedestrian: Lessons from Japanese mobile phone use. Paper presented to Mobile Communication and Social Change, the 2004 International Conference on Mobile Communication in Seoul, Korea, October 18-19. Retrieved September 4, 2007, from http://www.itofisher.com/mito/archives/ito.ppp.pdf

Ito, M., Okabe, D., & Matsuda, M. (Eds.) (2005). Personal, portable, pedestrian: Mobile phones in Japanese life. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

Jameson, F. (1979). Reification and utopia in mass culture. Social Text, 1, 130-148. Repr. in Jameson F. (1990) Signatures of the visible (pp. 9-34). New York: Routledge.

Kasesniemi, E.-L. (2003). Mobile messages: Young people and a new communication culture. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Kato, H. (2005). Japanese youth and the imagining of keitai. In M. Ito, D. Okabe, & M. Matsuda (Eds.), Personal, portable, pedestrian: Mobile phones in Japanese life (pp. 103-119). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kroker, A., Kroker, M., & Cook, D. (1989). Panic encyclopedia: A definitive guide to the postmodern scene. Montréal: New World Perspectives.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lesko, N. (2001). Act your age! A cultural construction of adolescence. New York and London: Routledge Falmer.

Ling, R. (2004). The mobile connection: The cell phone’s impact on society. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Ling, R. (2007). Mobile communication and the emancipation of teens. Keynote address to Mobile Media 2007, University of Sydney, 2-4 July.

Loader, B. (Ed.). (2007). Young citizens in the digital age: Political engagement, young people and new media. London: Routledge.

Lorente, S.(Ed.). (2002) Juventud y teléfonos móviles. Special issue of Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 57.

Lumby, C., & Fine, D. (2006). Why TV is good for kids: Raising 21st century children. Sydney: Pan Macmillan.

Lunn, J. (2007, March 15) ‘You lookin’ at me? I doubt it.’ Sydney Morning Herald, 3.

Matsuda, M. (2005). Discourses of Keitai in Japan. In M. Ito, D. Okabe, & M. Matsuda (Eds.), Personal, portable, pedestrian: Mobile phones in Japanese life (pp. 19-40). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Meikle, G. (2002). Future active: Media activism and the Internet. New York: Routledge.

Meyrowitz, J. (1985). No sense of place: The impact of electronic media on social behaviour. New York: Oxford University Press.

McGuigan, J. (2006). Mobility. Fifth-Estate-Online: International Journal of Radical Mass Media Criticism. Retrieved September 6, 2007, from http://www.fifth-estate-online.co.uk/comment/mobility.html

McGuigan, J. (2005). Towards a sociology of the mobile phone. Human Technology, 1, 1, pp. 45-57.

Middleton, C. (2007). Illusions of balance and control in an always-on environment: A case study of Blackberry users. Continuum, 21(2), 165-178.

Montgomery, K. (2007). Generation digital: Politics, commerce, and childhood in the age of the internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Morley, D. (2000). Home territories: Media, mobility and identity. London: Routledge.

Neilsen, B., & Rossiter, N. (Eds.) (2005). Multitudes, creative organisation and the precarious condition of new media labour. Special issue of Fibreculture Journal, 5, http://journal.fibreculture.org/issue5/index.html

Okada, T. (2005). Youth culture and the shaping of Japanese mobile media: Personalization and the keitai Internet as multimedia. In M. Ito, D. Okabe, & M. Matsuda (Eds.), Personal, portable, pedestrian: Mobile phones in Japanese life (pp. 41-60). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Poynting, S., & Morgan, G. (Eds.). (2007). Outrageous!: Moral Panics in Australia. Hobart: Australian Centre for Youth Studies.

Pump, B. (2005, September 30) iPod as religion. The Daily Iowan.

Rheingold, H. (2002). Smart mobs: The next social revolution. Cambridge MA: Perseus

Satchell, C. (2003). The Swarm: Facilitating fluidity and control in young peoples’ use of mobile phones. Proceedings of OzCHI 2003: New directions in interaction, information environments, media and technology. Brisbane, Australia. November, 2003.

Schneider, H. (2007) The reporting mobile: A new platform for citizen media. In K. Nyíri (Ed.), Mobile studies: Paradigms and perspectives. Vienna: Passagen Verlag.

Scifo, B. (2005). The domestication of the camera phone and MMS communications: the experience of young Italians. In Kristóf Nyíri (Ed.), A sense of place: The global and the local in mobile communication (pp. 363-74). Vienna: Passagen Verlag.

Sefton-Green, J. (Ed.) (1998). Digital diversions: Youth culture in the age of multimedia. London: Routledge.

Shade, L. R. (2007). Feminizing the mobile: Gender scripting of mobiles in North America. Continuum, 21(2), 179-190.

Sheahan, P. (2005). Generation Y: Thriving and surviving with Generation Y at work. Victoria: Hardie Grant Books.

Sullivan, N. P. (2007) You can hear me now: How microloans and cell phones are connecting the world’s poor to the global economy. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Taylor, A. (2006, October 11). ‘Attack of the Killer iPod.’ Sydney Morning Herald, 4.

Thomas, A. (2007). Youth online: Identity and literacy in the digital age. New York: Peter Lang.

Thompson, K. (1998). Moral Panics. London: Routledge.

Von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Urry, J. (2007). Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity.

Wellman, B. (2001). Physical place and cyberspace: The rise of personalized networks. International Urban and Regional Research, 25, 227-252.

Wellman, B., Hampton, K., Isla de Diaz, I., & Miyata, K. (2003). The social affordances of the Internet for networked individualism. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 8(3). Retrieved September 5, 2007, from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol8/issue3/wellman.html

Williams, R. (1974). Television: Technology and Cultural Form. London: Fontana.

Woolgar, S. (2005). Mobile back to front: Uncertainty and danger in the theory-technology relation. In R. Ling & P.E. Pedersen (Eds.), Mobile communications: Re-negotiation of the social sphere (pp. 23-43). London: Springer.

Wang, J. (2005). Youth culture, music and cell phone branding in China. Global Media and Communication, 1, 185-201.

Footnotes:

1 Fortunati describes ‘semi-socialised individualism’ as ‘an individualism which is socialized more on a high amount of contacts rather than few closer and somewhat closer relationships and which communicates in a reduced modality (the few words of a SMS)’ (Fortunati & Yang, 2005).

About the Authors

Kate Crawford is Associate Professor in the Journalism and Media Research Centre, the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia (k.crawford@unsw.edu.au). She is the author of Adult Themes: Rewriting the Rules of Adulthood (2006),which critiques age and generational categories. Adult Themes won the Manning Clark National Cultural Prize for 2006. Kate has been awarded an ARC Postdoctoral Fellowship for a study of mobile media and youth culture.

Gerard Goggin is Professor of Digital Communication, and Deputy Director of the Journalism and Media Research Centre, the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia (g.goggin@unsw.edu.au). He is author or editor of a number of books on mobiles, Internet, and new media, including Mobile Technologies: From Telecommunications to Media (2008; with Larissa Hjorth), Internationalizing Internet Studies (2008; with Mark McLelland), Mobile Phone Cultures (2007), Cell Phone Culture (2006), Virtual Nation: The Internet in Australia (2004), and Digital Disability (2003). Gerard holds an ARC Australian Research Fellowship for a study of mobile phone culture. He is editor of the journal Media International Australia.

Contact Details

Associate Professor Kate Crawford

Centre for Social Research in Journalism and Communication

University of New South Wales

Sydney 2052 NSW Australia

k.crawford@unsw.edu.au

Gerard Goggin

Professor of Digital Communication & Deputy Director

Centre for Social Research in Journalism and Communication

University of New South Wales

Sydney 2052 NSW Australia

g.goggin@unsw.edu.au