Beyond Globalisation: Rethinking the Scalar and the Relational in Global Media Studies

Beyond Globalisation: Rethinking the Scalar and the Relational in Global Media Studies

— Media and Communications, Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology

Abstract

This paper traces how the concept of globalisation has been understood in media and communications, and the ongoing tension as to whether we can claim to be in an era of ‘global media’. A problem with this discussion is that it continues to revolve around a scalar understanding of globalisation, where the global has superseded the national and the local, leading to a series of empirically unsustainable, and often misleading, claims. Drawing upon recent work in economic and cultural geography, I will argue that a relational understanding of globalisation enables us to approach familiar questions in new ways, including the question of how global large media corporations are, global production networks and the question of ‘runaway production’, and the emergence of new ‘media capitals’ that can challenge the hegemony of ‘Global Hollywood.’

Introduction

As the 20th century entered its closing decade, the concept of globalisation became ever more seen and heard as “a key idea by which we understand the transition of human society into the third millennium” (Waters, 1995: 1), but with ever-decreasing precision of meaning (Sinclair, 2004: 65). The 1990s witnessed a boom in globalisation theory, and even if much of that work has been subject to critique in more recent years, globalisation theory continues to play a central role in global media studies.

This is most apparent in the pervasive assumption that the world’s media are now dominated by a relatively small number of transnational corporations (TNCs). Herman and McChesney (1997) argued that “The … global media system is dominated by three or four dozen large transnational corporations with fewer than ten mostly US based media conglomerates towering over the global market” (Herman & McChesney, 1997: 1).

Steger (2003) observed that “To a very large extent, the global cultural flows of our time are generated and directed by global media empires that rely on powerful communication technologies to spread their message … During the last two decades, a small group of very large TNCs have come to dominate the global market for entertainment, news, television, and film” (Steger, 2003: 76).

In a review of media and cultural globalisation literature, Held et al. (1999) concluded: “There can be little doubt that … a group of around 20-30 very large MNCs dominate global markets for entertainment, news, television, etc., and they have acquired a very significant cultural and economic presence on nearly every continent” (Held et al., 1999: 347).

Recently, Sussman (2007) has argued that “Worldwide … the mass media are controlled by between 70 and 80 first- and second-tier corporations”(Sussman, 2007: 360).

Other core propositions in global media studies have followed from the assumption that control over media markets has come to be increasingly dominated by a small number of globally integrated TNCs. In particular, this global concentration of media ownership and control links with arguments associated with the strong globalisation proposition that the period since the 1980s has seen a qualitative shift in the pattern of economic, social, political and cultural relations within and between states and societies, as distinct from a quantitative change, or extensions and intensifications of more longstanding trends.

Giddens (1997) argued that we were witnessing the globalisation of modernity, which “is changing everyday life, particularly in the developed countries, at the same time as it is creating new transnational systems and forces … taken as a whole, globalisation is transforming the institutions of the societies in which we live” (Giddens, 1997: 33). Held et al. presented a transformationalist account of globalisation, where “at the dawn of a new millennium, globalisation as a central driving force behind the rapid social, political and economic changes that are reshaping modern societies and world order” (Held et al., 1999: 7).

Hardt and Negri (2000) argued that “Over the past several decades … we have witnessed an irresistible and irreversible globalisation of economic and cultural exchanges … [and] declining sovereignty of nation-states and their inability to regulated economic and cultural exchanges” (Hardt & Negri, 2000: xi-xii). Herman and McChesney concluded that “[f]ew eras in history have approached this one for tumult and rapidity of change, and key hallmarks of the era have been the spread of an increasingly unfettered global capitalism, a global media and communications system, and the development of revolutionary communications technologies” (Herman & McChesney, 1997: 205).

Castells (1996) identified global electronic communications as generating a culture of real virtuality, where “the new communication system radically transforms space and time … [and] localities become disembodied from their cultural, historical, geographic meaning, and reintegrated into functional networks … inducing a space of flows that substitutes for the space of places” (Castells, 1996: 375). For Castells, “the space of flows of the Information Age dominates the space of places of people’s cultures”, with the result being that “the network society disembodies social relationships … because it is made up of networks of production, power, and experience, which construct a culture of virtuality in the global flows that transcend time and space” (Castells, 2000: 369-370).

Underpinning many of these analyses is the view that there been a scalar shift in social relations arising from globalisation that is of such a scale that the analytical tools by which we understand social processes in the 21st century are fundamentally different to those which were applicable to 20th century societies.

John Sinclair’s observation on globalisation theories – that their meaning has become less clear as the use of the concept has become more pervasive – captures two important points about how the concept has developed from the early 1990s to the present. The first is that the term certainly experienced a boom throughout the 1990s, and that it became, as Tomlinson has argued, ”the buzz-word of the 1990s, just as postmodernism was the intellectual vogue of the 1980s” (Tomlinson, 2003: 10). Indeed, one can trace an arc in academic publications on globalisation that is bracketed at one end by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the demise of Soviet and East European communist states in 1989-90, and at the other by the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon in the United States. The latter threw into question some core assumptions of globalisation theory, such as the assumption that Western powers (and the US in particular) had achieved decisive military, political and cultural hegemony over the world and that a homogeneous global culture was emerging, but even in the case of September 11 and the subsequent ‘War on Terror’, the assumption that the clash of cultures and ideologies has become essentially global in its nature can still be put forward (e.g. Barber, 2003; Hardt & Negri, 2004).

The second point is that, in contrast to postmodernism, globalisation theories have tended to travel light on questions of ontology and epistemology, preferring instead to couch claims about an epistemic shift in “an empirical reality … focused in certain emblematic events” (Tomlinson, 2003: 11). Indeed, many of these accounts present globalisation as the unfolding of an immanent logic, whether of capitalism as a world-system (e.g. Herman & McChesney), modernity as a socio-cultural process (e.g. Giddens), or both (e.g. Castells). Held and McGrew defined globalisation in terms of such a build-up of long-standing tendencies of capitalist modernity to the point where they come to constitute a scalar shift:

Globalisation … denotes the expanding scale, growing magnitude, speeding up and deepening impact of transcontinental flows and patterns of social interaction. It refers to a shift or transformation in the scale of human organization that links distant communities and expands the reach of power relations across the world’s regions and continents (Held & McGrew, 2002: 1).

The difficulty is that the evidence presented for such scalar shifts has always existed alongside counter-evidence, so that the salience of globalisation as an overarching descriptor could vary depending upon the angle from which one chose to look. A range of markers of globalisation can be used, that range from economics and finance to culture and communication, to geo-politics and law, and different observations can be made about its extent and significance depending upon the starting point that is chosen by the analyst (Flew, 2007).

One response to such conflicting trends and the difficulty of establishing solid empirical foundations to the claims of globalisation theory could be to reject the paradigm outright. Sparks (2007) takes such a position, arguing that “theories of globalisation … are so far from providing an accurate picture of the contemporary world that they are virtually useless” (Sparks, 2007: 152), and that any useful insights they have identified are better explained as aspects of capitalist development in its imperialist phase. Another response would be to see the term as essentially ideological, as Harvey (2005) does in his invocation of globalisation, neo-liberalism and postmodernism as something of an unholy trinity enabling a new assertion of capitalist class power on a transnational scale, subverting locally and nationally-based oppositional trade union and social movements and social-democratic politics more generally.

More generally, one could respond empirically by pointing out how the 2000s differed from the 1990s. The collapse of the Doha Round of trade talks brokered through the WTO in many ways symbolized this change in times. As a breakdown in negotiations between the United States in one camp and India and China in the other derailed the Doha round in July 2008, maybe it was time to say that the emperors of supranational and para-statal governance had no clothes after all, and we remained locked into a system of states that has existed in one form or another since the Treaty of Westphalia of the 17th century, as globalisation sceptics such as Hirst and Thompson (1996) argued?

The approach taken in this paper retains globalisation as a relevant concept for understanding contemporary socio-economic trends and their relevance to global media studies, but rejects strong globalisation theories as lacking an adequate historical and empirical grounding. The problem with globalisation theories has been a conceptual one deriving, perhaps paradoxically, from insufficient attention being given to the spatial dimensions of such changes, leading to the focus upon globalisation as marking a scalar shift in socio-spatial relations that is without historical precedent.

I am defining a scalar shift as one where the dominant mode of socio-spatial relations shifts from one level to another. One example from sociology is the idea that the dominant modes of social interaction and power relations have been shifting over time from localities and communities to territorially defined nation-states, and now from nation-states to the interconnected globe. This three-part structure maps onto a reading of socio-cultural relations that identifies the pre-modern or traditional, the modern, and the postmodern, so that there is reference to an era of postmodern globalisation (e.g. Kellner & Best, 1997). Connecting this to media studies and media history, there is a common tradition of associating print culture with modernity and television with globalisation and post-modernity (e.g. Barker, 1997), with the result being that such work in media and cultural studies sits comparatively easily with theories of globalisation defined in terms of a scalar shift beyond the territorially defined nation-states.

The assumptions about a scalar shift from the national to the global, and the accompanying lack of attention to spatial complexity, draws attention to the need to more explicitly foreground the contribution of geographical perspectives to an understanding of a phenomenon as explicitly spatial in its dimensions as globalisation. Ash Amin (2001) has defined the geographical perspective on globalisation in these terms:

Geographical theory … has been concerned with the spatiality of the contemporary world, and is interested in understanding whether places – cities, regions, and nations – are perforating as geographically contained spaces, how the insertion of places into geographically stretched relations matters, and how new geographical scales of organization and influence associated with globalisation are challenging old scales of identification and action (Amin, 2001: 6271).

Such an approach recognizes that scalar relations can change, but that such changes would mark shifts in processes that have long been multi-scalar in their nature, ranging across the local, the regional, the national, the international and the global.

This geographical perspective draws attention to the ways in which relations between these scales of social activity are transformed in ways that are interconnected and mutually constitutive, and what is referred to as the “spatial ontology of social organization” (Amin, 2002: 386). Most particularly, it focuses attention on the relational dimensions of socio-spatial change, moving away from conception of globalisation in terms of a ‘runaway world’ (Giddens, 2002) or “global flows that transcend time and space” (Castells, 2000: 370), towards a focus upon the ways in which geographical locations can become “clusters of overlapping network sites” (Amin, 2001: 6275), where there is an interlocking of activities across multiple planes of the global, the national, the regional and the local. Such a methodological starting-point draws attention to the need to develop different research agendas for global media studies to those premised upon metaphors of a fundamental scalar shift, or ”an irresistible and irreversible globalisation of economic and cultural exchanges” (Hardt & Negri, 2000: xi).

A Critique of Globalisation as Scalar Shift

At the core of many of the strong globalisation arguments are a set of interlocking economic, political, technological and cultural claims. It is argued that we now live in a truly global economy, integrated by networked information and communication technologies (ICTs), that have one the one hand weakened the political-economic power of the nation-state, and on the other generated a global media culture built upon shared symbolic experiences and the transformation of time-space relationships. Whether this is to be welcomed as the harbinger of a globally integrated economy and emergent global civil society (e.g. Legrain, 2002; Friedman, 2005), or opposed for its denial of the specificities of place, culture, national identity and territorial sovereignty (e.g. Barber, 2000), it is largely taken to be an empirically given fact of 21st century societies. It may be that the global financial crisis of 2008 will be taken as marking out a limit-point to what has been referred to as neo-liberal globalisation (McGuigan, 2005), but the evidence at this stage is not yet clear on this.

Global media are central to this perceived scalar shift in contemporary capitalist societies as the principal developers of the new global information and communication technologies and infrastructure, as large multinational corporations that are transforming national mediascapes, and as the principal bearers of information and images through which we make sense of events in distant places and generate shared systems of meaning and understanding across nations, regions and cultures. Giddens emphasized the extent to which “Globalisation … has been influenced above all by development in systems of communication, dating back only to the late 1960s” (Giddens, 2002: 10) while Castells argued that “under the informational paradigm, a new culture has emerged from the superseding of places and the annihilation of time by the pace of flows and by … the culture of real virtuality” (Castells, 2000: 370).

I will argue that behind these assumptions are a set of interlocking claims about the dimensions of globalisation as a fundamental scalar shift that do not stand up well to close empirical scrutiny. In doing so, the relevance of a relational frame derived from geographical perspectives will be observed.

Markets increasingly operate on a global scale, and are dominated by a diminishing number of transnational corporations (TNCs). One indicator for the reach and significance of TNCs is the Transnationality Index (TNI) developed by the United Nations Commission for Trade, Aid and Development (UNCTAD). The TNI which measures the transnationality of the world’s top 100 non-financial corporations on the basis of the percentage of assets, sales and employees outside of the corporation’s national home base.

Using the TNI, Dicken (2003a) found that the degree of transnationality of these top 100 non-financial TNCs, increased from 51.6 percent in 1993 to 52.6 percent in 1999, which would not indicate a significant shift in the scale of global operations of these largest corporations, who would be expected to be at the forefront of globalisation. On average, most of the world’s largest non-financial TNCs continue to undertake 40-50 percent of their activities in their ‘home’ country, and those with the largest proportion of activities outside of their home country tend either to be from countries with smaller home markets (e.g. TNCs from Switzerland, Canada, Australia or Sweden, rather than the United States or Japan), or to be in resource-related industries such as mining or petrochemicals, where the primary resource assets are globally dispersed. Importantly, media and entertainment industries are among the least globalised, with only Thomson Corporation (Canada) being among the top 100 non-financial TNCs from the media sector in 2005 (UNCTAD, 2007). Insofar as communications corporations are developing their global capacities, this is a much stronger tendency in telecommunications than in media, which is consistent with Glyn and Sutcliffe’s (1999) observation that service industries tend, as a general rule, to be less globalised than those in manufacturing, mining and infrastructure provision. These TNCs organize their activities on a global scale, and are less and less constrained by the policies and regulations of nation-states.

If we understand a global corporation to be “a firm that has the power to co-ordinate and control operations in a large number of countries … [and] whose geographically-dispersed operations are functionally integrated”, as distinct from “national corporations with international operations (i.e. foreign subsidiaries)” (Dicken, 2003a: 225), then there is an extensive literature from fields such as business management, economic geography and economic sociology that indicates that the truly global corporation remain something of a myth, outward appearances to the contrary. Doremus et al. (1998) did not find evidence of convergence in the institutional and policy environments that faced businesses as a result of globalisation, and that the world's leading multinationals continue to be shaped decisively by the policies and values of their home countries, and that their core operations are not converging to create a seamless global market Gertler has observed that “the enduring path-dependent institutions of the nation-state retain far greater influence over the decisions and practices of corporate actor than the prevailing wisdom would allow” (Gertler, 2003: 12), while Dicken has argued that “TNCs … remain, to a very high degree, products of the local ‘ecosystem’ in which they were originally planted. TNCs are not placeless; ‘global’ corporations are, indeed, a myth” (Dicken 2003a: 44).

The power of nation-states is in decline, with many of their core operations being superseded by the laws and regulations established by supra-national governmental institutions. Claims about the “declining sovereignty of nation-states and their increasing inability to regulate economic and cultural exchanges” (Hardt ¶ Negri, 2000: xii), are not supported by empirical evidence. Weiss (1999) has argued that of seven possible indicators that economic globalisation has transcended the significance of national economies, there is only one case – finance – where genuinely global markets have emerged. In other major indicators – such as production for domestic markets as compared to exports, financing of domestic investment by domestic savings rather than foreign direct investment, the degree of integration of equity markets worldwide, the orientation of corporate decision-making in ‘home’ markets, and trade patterns being primarily regional rather than global – there was little substantive shift between the 1970s and the 1990s.

Moreover, comparative trends in levels of taxation, welfare expenditure or industrial policy do not reveal a trend towards convergence; rather diverse institutional forms of national capitalisms retain significance, with the Anglo-Saxon liberal market economies, continental European coordinated market economies, and East Asian coordinated market economies remaining distinctive ideal-types, joined now by models as diverse as those of China, Russia, India and the Middle East (Weiss, 2003; Perraton & Clift, 2004). In the economic realm, the ‘decline of the nation-state’ literature has conflated the reduced capacity to pursue certain types of macroeconomic policy (e.g. deficit financing of government spending, capital and exchange rate controls) with a decline in the capacity of nation-states to manage the economy overall and to pursue national economic policy objectives in the context of a more integrated global economy. Work on comparative media policy such as that of Hallin and Mancini (2004) indicates limitations to the convergence thesis as applied to North American and European media systems, and there is considerably less evidence of media policy convergence in the Asian region (Thomas, 2006).

Globalisation generates increasingly global media cultures

The global media cultures thesis has two variants. The first, which goes back to UNESCO-supported research in the 1970s and 1980s (Nordenstreng & Varis, 1974; Varis, 1984), drew upon evidence of US domination of audiovisual trade to conclude that a one-way flow of media content formed the basis of cultural imperialism. The problems with this work were firstly the fact that the vast bulk of media content is not internationally traded, and secondly that empirical evidence from a range of nation and regions suggested that television systems tended to become more nationally-based over time (Tracey, 1988; Sepstrup, 1989). As Barker observed of these analyses, “a restricted range of studies has been used to generalize in an unsustainable manner and draw universal conclusions which then form the basis of global cultural theories” (Barker, 1997: 49). Tunstall (2007) has reinforced these findings with his claim that the global significance of US media is actually in decline, that most large nation-states are broadly (80-90 percent) media self-sufficient, and that while “a global or world level of media certainly does exist … [it] plays a much smaller role than national media” (Tunstall, 2007: xiv).

More recent globalisation theories have tended to link global media cultures to transnational media communications technologies (cable, satellite, Internet) and media events, to argue for what Giddens referred to as ‘disembedding’ or “the ‘lifting out’ of social relations from local contexts of interaction and their restructuring across indefinite spans of time-space’ as a feature of global modernity (Giddens, 1990: 21). These arguments rest upon assumptions about media and culture that are difficult to sustain empirically, and rest upon a conflation of culture and technology. The first is that culture is taken as synonymous with the media, and particularly with electronic media of mass communications. This not only downplays the ongoing significance of culture as lived and shared experience as distinct from mediated symbolic communication, but also ignores those cultural forms whose circulation is primarily local rather than global – the focus is almost exclusively on cinema and television, not the arts, music, live performance, literature, newspapers or radio (Flew, 2007). Second, media are understood in terms of their distribution technologies rather than their content, in a manner that is strongly framed by the speculative media theorists such as Marshall McLuhan (1964) and Jean Baudrillard (1990).

Again, the assumption that media content becomes more global as global distribution technologies are developed is frankly contradicted by the comparative history of national television systems which indicate that “passing through an initial stage of foreign dependence to a maturity of the national market is, if not universal, then certainly a common pattern” (Sinclair, 2004: 76). There is considerable evidence in the development of national television systems of an intersection between audience preferences for programming from their own country and in their own vernacular, development of local programming production capacity, and state policies to foster local television production and the use of television to promote a shared national cultural identity (Straubhaar, 1997; Sinclair, 2004). While such work needs updating in the context of Internet downloading sites such as YouTube to confirm whether national preference continues to exist in an age where new distribution technologies allow for a la carte television, it would be surprising if new technologies had eliminated national cultural preference, as it has never simply been a by-product of the technological affordances of the time. Global media are central to the separation of place and space, which is a defining feature of globalisation.

One trend that is generally associated with globalisation is a blurring of the lines between different spatial scales. Giddens (1990) described this as the blurring of the distinction between place and space, so that the intensification of global interconnectedness means the distinction between what is tangible and ‘local’ and what is external or ‘global’ is no longer tenable. Jessop (2000) has referred to the ‘relativisation of scale’ arising from the simultaneous occurrence of time-space distanciation, which “involves the stretching of social relations over time and space so that relations can be controlled or coordinated over longer periods of time (including into the ever more distant future) and over longer distances, greater areas or more scales of activity”, and time-space compression, involving ”the intensification of ‘discrete’ events in real time and/or the increased velocity of material and immaterial flows over a given distance … linked to changing material and social technologies enabling more precise control over ever shorter periods of action” (Jessop, 2000: 340).

The relativisation of scale is certainly a core concept associated with globalisation in all of its dimensions. The danger is that the association of globalisation with the emergence of new spatial relations that are more disembedded and abstract presumes that place and territory, by contrast, is given in advance and then ‘acted upon’ by abstract forces associated with globalisation. Scholte provides an example of this scalar logic in defining global relations as “social connections in which territorial location, territorial distance and territorial borders do not have a determining influence” (Scholte, 2000: 179). Not surprisingly, the implication of such argument is to look to place, locality and nation – that which is territorially fixed – as a site of resistance to deterritorialisation. For example, Lloyd (2000) argues that faced with ”this sense of destruction of local differences, and therefore of local identity … it is nationalism that is the only force that is capable of withstanding, even defeating globalisation” (Lloyd, 2000: 266-267). Aside from anthroporphising globalisation so that it moves from being a descriptor for a complex range of social processes to becoming an entity in its own right, this approach has the consequence of identifying some political struggles around globalisation as being more ‘authentic’ than others e.g. those of local residents over ethnic minorities or migrant workers, or the defence of national culture over the media of diasporic communities. Amin describes this as:

A peculiar politics of place in which relations within localities are cast as good and meaningful, and contrasted to bad and totalising external relations. Its peculiarity follows from the ontological separation of place (read as in here, and intimate) and space (read as out there, and intrusive) as distinctive scalar realms (Amin, 2001: 6273).

What is lacking here is a sense that, as the local and the global become interconnected, the nature of place is itself transformed, and the “spatial ontology of social organization” comes to incorporate a multiplicity of interscalar relations (Amin, 2002: 386). An example that Amin gives is that of contemporary London. London possesses populations whose activities primarily sit within global circuits of accumulation (e.g. financiers in the City of London) as well as those who have a more localized and grounded relationship to the city and to particular regions, but its highly multicultural population means that many people are engaged in various forms of diasporic brokering (import-export trade, provision of cultural services etc.) that operate on a scale beyond the national, but are not activities being undertaken by a global cosmopolitan elite.

Globalisation leads to a ‘race to the bottom’, where globally mobile capital can “play off workers, communities and nations against one another” (Crotty et al., 1998: 118).

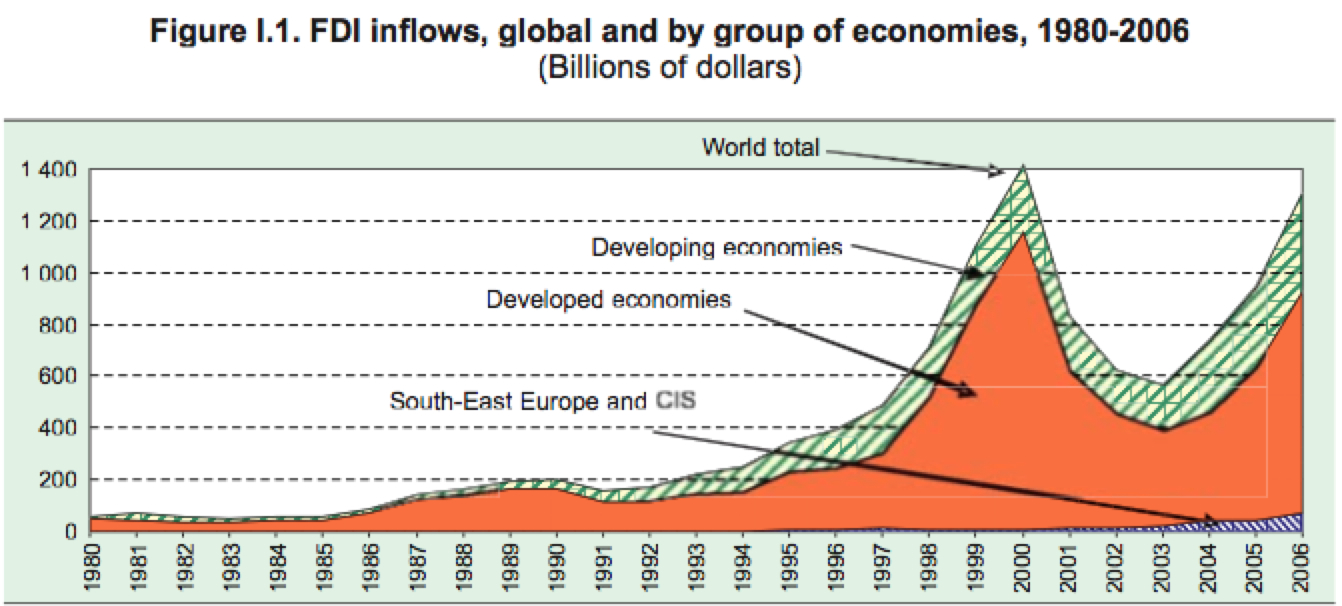

One of the paradoxes of globalisation debates is that, while the discussion is overwhelmingly about whether foreign investment benefits or disadvantages developing countries, the bulk of foreign direct investment (FDI) is in developed economies. Figure 1 (below) indicates that in 2006, over 60% of foreign direct investment was in developed economies, with the United States being the largest FDI recipient, and the United Kingdom second.

Source: UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2007: 3.

Whereas traditional theories of foreign investment have focused upon the relationship between ownership factors (the advantages that multinational corporations have in terms of access to finance, brand equity etc.), and location factors (availability of raw materials, lower-wage labour, host government incentives etc.), recent work on the multinational corporation has drawn attention to internalisation factors or the ability to capture localised sources of knowledge and apply them across multiple markets (Dunning, 2001a, 2001b). This is consistent with a shift in corporate global strategies from focusing primarily upon deriving greater profits from existing assets, by reducing costs through offshore production or selling into new markets, to strategies that focus upon “the creation, as well as the use, of resources and capabilities … [and] organize activities in order to create future assets” (Dunning, 2001a: 100).

Storper (1997) argues that the ‘off-shoring’ of work to low-wage economies, runaway production and a more polarized new international division of labour is only one possible scenario arising from economic globalisation. This deterritorialised economic development exists alongside what he refers to as territorialised economic development, or “economic activity that is dependent on territorially specific resources” (Storper 1997: 170). Territorialised production is that where product and services are not standardised, quality is prioritised by consumers and not only price, and production processes rely upon both specialist labour inputs and untraded interdependencies, or “conventions, informal rules, and habits that coordinate economic actors under conditions of uncertainty … [and] constitute region-specific assets” (Storper 1997: 4-5).

Storper observes that there is also a need to recognize globalisation that results from the “local, path-dependent, and highly embedded technological change” that has emerged in particular dynamic cities and regions, that “is a strong and positive driver of globalisation, … because it supplies scarce resources to the global economy in the form of temporarily unique knowledge embedded in products or services” (Storper, 2000: 49). In contrast to the belief that globalisation of trade, communications and access to technologies would lead to product standardisation, what is instead occurring is rather a dualistic development of technology, geographies, organisation and innovation, with an increased premium placed upon that which is specialised and non-standardised:

It now appears that development … depends, at least in part, on destandardization and the generation of variety. The increasing spatial integration of markets for standardized products bids away monopolistic rents, while automation takes away employment, and advantage accrues to low-wage, low-cost areas. The only way out of this dilemma is to recreate imperfect competition through destandardization, the source of scarcity (Storper, 1997: 32-33).

Rethinking Media Globalisation

One feature of the literature on media globalisation is the pervasiveness of the view that global media are dominated by a relatively small number of transnational corporations. At the same time, research on national and regional media systems continues to attest to the continued centrality of national media corporations in these media ecologies.

There is an extensive history of research on Latin American media (e.g. Waisbord, 2000; Struabhaar, 2001; Sinclair, 2004, 2005) that points to the continued dynamism and centrality of Televisa (Mexico), Globo (Brazil) and Clarin (Argentina) in an age of satellite competition from FOX and CNN. Work on Asian media similarly indicates the struggle to develop pan-Asian services that can be competitive in different national markets even after over 20 years of widespread satellite and cable service availability (Thomas, 2005), and while the Middle East has seen regional satellite services achieve dominance over national broadcasters, it has conspicuously been pan-Arab services such as Al-Jazeera and Al Arabiya rather than Western media that have been in the ascendancy (Dajani, 2005; Zayani, 2005). Then of course there is China, where the world’s fastest growth in television ownership has not dislodged the hegemony of the state-run CTV services despite the availability of alternatives, and where the scope for Western media giants to expand operations has remained highly circumscribed and contingent on state policy (Zhao & Guo, 2005: Wang, 2008).

Paradoxically, then, one of the obstacles to the call to internationalize media studies (see e.g. Curran & Park, 2000; Couldry, 2007) is global media studies itself, or at least the version of it that has largely accepted without critical scrutiny the assumption of a scalar shift from discrete national media systems to a global mediascape dominated by a small number of transnational corporate behemoths.

There is work that questions media globalisation (Hallin & Mancini, 2004; Hafez, 2007), and one of the most intriguing recent contributions has come from Jeremy Tunstall, in his book The Media Were American: US Mass Media in Decline (Tunstall, 2007). Tunstall argues that 85 percent of total world audience time is devoted to domestically produced media, and only 15 percent to imported media, and that the share of national media has, contra globalisation theory, been increasing since the 1960s as more nations develop media production capacities and governments invest in media as an expression of national culture (Tunstall, 2007: 321).

The point to be made here is not a simple inversion of the claim that there has been a scalar shift with globalisation from the national to the global by reasserting the continued significance of national media space. It remains the case, as Couldry has argued, that ‘media always involve a rescaling of territory’ (Couldry, 2007: 248), and that there is a need for an understanding of media cultures that is ‘translocal’, and recognises media as being multi-scalar. The point is rather that is it not a simple linear move from the local to the national to the global, but instead there is a complex web of scalar relationships that link to complex cultural and economic geographies of place. In order to best understand this, we need to conceive of globalisation in relational rather than scalar terms. The remainder of this paper seeks to open up such thinking around the questions of:

Whether the world’s largest media corporations can be considered to be global corporations;

Whether the globalisation of film and television production is primarily a cost-driven process of ‘runaway production’;

The scope for new media capitals to emerge that challenge the hegemony of ‘Global Hollywood’.

How Global are Media Corporations?

When talking about global media corporations, there is an important distinction to be made between media corporations operating on a truly global scale, and nationally-based corporations with overseas operations. Forms of media globalisation that revolve around the sale of media and creative products and services in many markets have existed at least since the expansionary strategies of the Hollywood majors into Europe and Latin America in the 1920s. They are not synonymous with the development of a geographically dispersed global assets base, arising from foreign direct investment, strategic partnerships, and mergers and acquisitions. They are more akin to what Dicken refers to as “national corporations with international operations (i.e. foreign subsidiaries)” (Dicken, 2003a: 225).

On the basis of the UNCTAD Transnationality Index, the media industries are not particularly transnational. UNCTAD data for 2003 found that four media or media-related corporations were in the top 100 non-financial TNCs in term of their degree of transnationality – Vivendi Universal (20), News Corporation (22), Thomson Corporation (65) and Bertelsmann (98).

UNCTAD’s 2004 data saw Vivendi Universal and News Corporation disappear from this list. In the case of Vivendi, this reflected its declining corporate fortunes, and in the case of News Corporation this was because it had relocated its corporate head office from Australia to the United States (UNCTAD, 2006; Flew, 2007). By 2005, only Canada’s Thomson Corporation appeared as a media corporation in the top 100 non-financial corporations in terms of the TNI.

The finding that media corporations are less global than other sectors is consistent with the observation of Glyn and Sutcliffe (1999) that non-financial service industries tend to be less globalised, and their products less globally traded, than those of the manufacturing sector. Insofar as convergent media and communications industries have been more transnational in recent years, the major growth has been in telecommunications rather than the media and entertainment sectors.

If we take the world’s four largest media corporations in 2004 – Time Warner, Disney, Viacom and News Corporation – only one of these (News Corporation) could be said to have approached the status of a global corporation. By contrast, companies such as Time Warner, Disney and Viacom have a small share of their overall asset base outside of North America. Indeed, Time Warner does not list its assets located outside of the United States in its Annual Report, since the overwhelming bulk of its international revenues are derived from the sale of US copyrighted products abroad, and therefore constitute intangible assets based upon the commercial value of product titles. If we analyse international activity in terms of revenues acquired outside of the home country, and if we approach News Corporation as a US company, we find that Time Warner, Disney and Viacom have a comparable pattern of operations, deriving 20–25 percent of their total operating revenues from outside of North America, with News Corporation being the significant outrider, deriving 44 percent of its revenues from outside of the United States (Table 1).

While there is some evidence of the growing importance of international activities to these corporations, it is the case that “the activities of large media companies appear to be less globalised than is the world economy as a whole” (Sparks, 2007: 144). Updating these figures to 2007 does not reveal significant shifts (Table 2).

Table 1

|

|||||

|

Total assets ($US bn) |

Foreign assets as % of total assets |

TNI |

Revenue earned in North America (%) |

Revenue earned outside North America (%) |

Time Warner |

122 |

* |

* |

79 |

21 |

Disney |

53 |

14 |

18.5 |

77.5 |

22.5 |

News Corporation |

56 |

19 |

32 |

56 |

44 |

Viacom |

15 |

5 |

10 |

78 |

22 |

Source: Flew, 2007: 87.

Table 2

|

|

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

Time-Warner |

Foreign assets as % of total |

* |

* |

* |

|

Revenues earned outside of North America as % of total |

21 |

20 |

18 |

News Corporation |

Foreign assets as % of total |

19 |

19.5 |

24 |

|

Revenues earned outside of North America as % of total |

46 |

44.5 |

47 |

Disney |

Foreign assets as % of total |

14 |

13 |

14.5 |

|

Revenues earned outside of North America as % of total |

22.5 |

24.5 |

23 |

For a fuller understanding of the possibilities and pitfalls of large media corporations becoming more global in their orientation, as distinct from being national companies with international operations, it is Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation that is the exemplar. However, we lack a comprehensive analysis of News Corporation that is comparable to Wasko’s (2001) study of Disney, and much of the available literature is focused upon Rupert Murdoch as a distinctive media mogul more than on News Corporation as a global business (see e.g. Shawcross, 1992; Chenoweth, 2002; Rohm, 2003). An Australian company until the relocation of its head office from Adelaide to Delaware in 2004, it is a genuinely multinational media conglomerate, with investments across all media platforms over five continents.

A detailed assessment of News Corporation’s global strategies is beyond the scope of this paper (see Flew, 2007: 88-90 for an overview of key historical developments), but it would reveal some notable successes (such as the expansion of British newspaper interests in the 1970s and establishment of the FOX Television Network in the US in the 1980s), some notable failures (the attempt to establish STAR TV as a pan-Asian satellite television service in the early 1990s, and the attempt to use the takeover of DirecTV in the US in the 2000s as the basis for a Sky Global Network of satellite TV services), and ventures where the outcome remain uncertain, most notably the ventures into mainland China through the Phoenix satellite television channel (Curtin, 2005; Thomas, 2006; Dover, 2007).

Such work should consider the extent to which News Corporation has relied upon local partners in its international expansion ventures, along the lines of ‘alliance capitalism’ discussed by Dunning (2001a), and its sensitivities to content variation across its multiple services in different countries and continents. It was a News Corp executive who observed in 1995, after STAR TV was forced to move from being a pan-Asian English language service to a multi-local service that “There’s no money to be made in cultural imperialism” (quoted in Sinclair, 1997: 144).

Global Media Production: A ‘Runaway’ Model?

There has been considerable debate about whether the growth in international film and television production form multiple locations represents the rise of new production centres that may compete with the dominant Hollywood cluster, or whether this is cost-driven ‘off-shoring’ of production that simply consolidates the dominance of ‘Global Hollywood’.

Miller et al. (2001) have proposed that the global media production system is structured around what they term the New International Division of Cultural Labour (NICL). For Miller et al., what is distinctive about the current phase of globalisation of predominantly US based audiovisual media industries is that they have been structurally separating the ‘activities of the hand’ – the production of films and television programmes as material artefacts – from the ‘activities of the mind’, or the development of ideas, concepts, genres and programme forms.

In a mode of thought that is derived from Adam Smith as well as Karl Marx, Miller et al. argue that production processes (‘activities of the hand’) are being progressively globalised in search of lower labour costs and other costs of production, while the generation and ownership of intellectual property (‘activities of the mind’) that involves the creation and exploitation of new product concepts remain highly centralized. Evidence of this is seen, for example, in the global concentration of ownership of intellectual property such as copyright, patents, trademarks and designs.

On a further note, Miller et al. argue that attempts by governments around the world to attract foreign investment in film and television production on the basis of tax incentives and lower labour costs simply replicate dependency relations across three tiers of global audiovisual production: (1) the US as global centre, where knowledge, finance and decision-making remains concentrated; (2) a semi-peripheral or intermediate zone of (predominantly English-language) countries such as Canada, Britain, Australia and New Zealand, where production can be transferred to take advantage of costs relative to exchange rates; and (3) the rest of the world, which largely functions as either a scenic backdrop or as a source of cheap labour, and is completely dependent on the centre for one-off production. This capacity to redistribute work globally has the further consequence of ‘disciplining’ American cultural labour by demonstrating the capacity to shift work around the globe. Through the NICL, Miller et al. argue, “MNCs can discipline both labour and the state, such that the latter is reluctant to impose new taxes, constraints or pro-worker policies in the face of possible declining investment” (Miller et al., 2001: 52).

Global Hollywood has opened up an important new debate in global media studies, and a distinctive feature of the work of Miller et al. is that they have moved beyond the question of media effects that has plagued previous work in the critical political economy tradition grounded in cultural imperialism, by shifting the focus from consumption and dominant ideologies to a focus on labour conditions and global production networks. This argument intersects with the concerns strongly expressed among producer organisations and labour unions in the United States about the impact of runaway production on the US film and television production industry. The US Department of Commerce estimated the economic losses to the US film and television industries from runaway production to be over $10 billion in 1998, up from $2 billion in 1990, and the Film and Television Action Committee and the Screen Actors’ Guild have been major lobbyists of policy-makers to resist industry plans to send production ‘offshore’ to countries such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

The US film and television industry claims about runaway production have gone uncontested. First, it is apparent that estimates on the extent to which it is occurring vary enormously, and are typically tied to particular interest groups. Estimates of the value of US-developed productions produced outside of the US in 1998 vary from $1.7 billion to $10.3 billion, with the lower figure coming from a Canadian-based consulting firm and the higher figure from a US-based production firm acting on behalf of the Screen Actors Guild (McDonald, 2006: 32-33).

Moreover, insofar as much of this production occurred in Canada, consultants acting on behalf of Canadian interests have argued that these figures needs to be considered alongside the $1.3 billion deficit that Canada has in audiovisual trade with the US, as well as variations in the exchange rate between the US and Canadian dollars, and the fact that Canadian production crews could hardly be considered to be exploited for their labour at the rates at which they are paid (McDonald, 2006: 33-34).

Second, Goldsmith and O’Regan (2003) have questioned the use of the term ‘runaway production’, arguing that film production is increasingly internationalised and organised through global production networks, whereas the term ‘runaway production’ assumes that all aspects of a film or television production should occur in the one nation. Moreover, they question the clear distinction drawn in these accounts between ‘economic’ and ‘creative’ factors as determinants of production location decisions. They argue that such approaches imply a limited understanding of creativity, which downplays the relevance of the creativity and skills of those working in the emergent locations (see Figure 1 for factors influencing production location decisions).

Third, a significant aspect of the critique of offshore production arises from American cultural nationalism, as illustrated by McDonald’s argument that:

The movie industry is a national treasure that many Americans take for granted. Simultaneously, many in America would agree that movies, studios, and Hollywood (as a physical location and as a part of the American psyche) are treasures the nation should not export (McDonald, 2006: 81).

Noting this is not to say that cultural nationalism is automatically wrong in principle. It is to note, however, that such arguments are now coming from the United States, when US trade representatives and industry bodies such as the motion Pictures Association of America (MPAA) have long dismissed claims for a ‘cultural exception’ to bilateral and multilateral agreements to free up international trade as sentimental, backward-looking and denying the free expressions of popular preference exhibited through commercial markets (Grant & Wood, 2004).

In order to consider this question in more depth, two insights from geographical research are important. The first is to recognize, as noted earlier, that cost-driven globalisation is only one aspect of international expansion, and that the NICL concept draws upon a model of foreign direct investment whose focus on cost reduction as the primary driver has been challenged in more recent literature on multinational corporations (e.g. Storper, 1997; Dunning, 2001a, 2001b; Rugman & Verbeke, 2001).

This literature has drawn attention to the role played by both foreign direct investment and the formation of cross-border strategic alliances in corporate strategies for ‘the harnessing, creation, and organization of a range of knowledge-related assets from different locations as a competitive advantage in its own right’ (Dunning, 2001b: 57). In the case of so-called ‘offshore’ or ‘runaway’ film and television production, such work would suggest that while cost factors may have been important first drivers of the relocation of film and television production out of the United States to other countries, the extent to which this is sustained over time will depend upon the extent to which sustainable locational clusters emerge in alternative production sites that make it worthwhile to continue to produce in such locations after short-term cost advantages have dissipated. There is considerable work to be done on whether patterns are emerging in media and entertainment industries that are comparable to other sectors where:

Multinational enterprises are engaging in foreign direct investment specifically to tap into, and harness, country- and firm-specific resources, capabilities, and learning experiences … [and] may use their foreign affiliates or partners as vehicles for seeking out and monitoring new knowledge and learning experiences; and as a means of tapping into national innovatory or investment systems more conducive to their dynamic competitive advantages (Dunning, 2001a: 20).

This focus on the internalisation or knowledge-building advantages of multinational expansion has merged alongside the dramatic growth of global production networks. Discussion about ‘runaway’ production has largely focused upon the experience of the countries that capital investment has moved from, with considerably less consideration of impacts on the recipient nation. Ernst and Kim (2002) have argued that global production networks constituted the major organizational innovation in global corporate operations in the late 20th century, enabling new strategies for international knowledge diffusion across national boundaries, and creating new opportunities for knowledge capture and local capability formation in hitherto lower-cost locations outside of the head office heartlands of North America, Western Europe and Japan. They argue that:

A transition is underway from ‘multinational corporations’, with their focus on stand-alone overseas investment projects, to ‘global network flagships’ that integrate their dispersed supply, knowledge and customer bases into global (and regional) production networks (Ernst & Kim, 2002: 1418).

For those countries that receive these new forms of foreign direct investment, the ability to capture new forms of knowledge-based value is vitally dependent upon the capacity of local suppliers integrated into these global production networks to meet the expectations of the global flagships, while at the same time continuously upgrading their absorptive capacity. Absorptive capacity refers to the combination of the existing knowledge base and the intensity of commitment to acquiring new knowledge.

Ernst and Kim use the concept of ‘absorptive capacity’ to explain how Asian economies such as those of Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea moved up the value chain from being relatively low-cost suppliers to Western MNCs in the 1970s and 1980s to having their own leading global firms and being relatively high-wage, knowledge-intensive economies with high levels of localised innovation (cf. Yusuf, 2003). Similar thinking lies behind the strategy in China to develop ‘national champions’ in key economic sectors, whose capacity for innovation ‘piggy-backs’ off the knowledge acquired through partnerships with foreign investors (Nolan, 2004).

Henderson et al. (2002: 445) have identified global production networks as providing a framework that is “capable of grasping the global, regional and local economic and social dimensions of … globalisation’. They have noted a paradox in these production networks in that, while the networks themselves are not territorially defined, they work through social, political and institutional contexts that are territorially specific, principally – although not exclusively – at the level of the nation-state. This means that the actions of local firms, governments and other economic actors, such as trade unions, ‘potentially have significant implications for the economic and social outcomes of the networks in the locations they incorporate” (Henderson et al., 2002: 446).

Global production networks are thus partly deterritorialised in the sense used by Storper (1997), as they are not territorially ‘bound’ in the manner of firms operating primarily at the level of the national economy. They are, nonetheless, spatially embedded in multiple respects, including interpersonal networks (for example, key decision-makers in the MNC need to interact with key decision-makers in the host nation, in which there will be pre-existing social networks); being ‘anchored’ in particular national forms of governance (taxation systems, educational frameworks and so on); and institutional and cultural milieux, from which they can derive new forms of knowledge and draw upon distinctive well-springs of innovation.

The circumstances under which host nations can enhance and capture value through FDI embedded in global production networks will depend upon factors such as: the nature and extent of technology and knowledge transfer; the sophistication and adaptive capacity of local suppliers; whether skill demands increase over time (enabling a move from low-wage, low-skill ‘generic’ labour to higher-skill, more specialist work); and whether local firms can begin to develop their own organizational, relational and brand ‘rents’, or unique profit-generating attributes (Henderson et al., 2002: 449). In all of these areas, the roles played by national institutional influences, particularly those arising from government policy, are critical.

New Media Capitals?

While Miller et al. (2001) have argued that trends towards internationalisation of media production involves the loss of both cultural sovereignty and control over intellectual property rights for host nations, economic geographers such as Scott (2004) has argued that “the steady opening up of global trade in cultural products is now making it possible for various audiovisual production centres around the world to establish durable competitive advantage and to attack new markets” (Scott, 2004: 474). This raises the question of whether new media capitals may be emerging that present new competitive challenges to Hollywood hegemony. In his work on media capitals, Curtin has considered whether – as Tunstall has also argued – we may have already seen the peak of ‘Global Hollywood’, and the rise of alternative media production centres in a manner akin to that which occurred with industrial production in the 1970s:

Just as Hollywood throughout its history absorbed elements and artists borrowed from afar, so too are other media capitals adapting the genres, visual conventions, technologies, and institutional practices of Hollywood to local conditions. Like Detroit in the 1960s, Hollywood today produces big bloated vehicles that command the fascination of audiences around the world. Yet, at the same time, it increasingly must take account of competitors who fashion products for more specific markets, using local labour, materials and perspectives. Such programs are not only cheaper to produce but also more attractive to target audiences because they are more culturally relevant (Curtin, 2004: 292).

Keane (2006) has provided an analogous means of conceiving of the relationship between global media and the emergence of new production centres in East Asia. Reflecting that the moment of ‘import-substitution’, or promotion and protection of local media production in order to redress the deleterious impact of global media and ‘cultural imperialism’, has now mostly passed in East Asia, Keane identifies five means through which regional production centres can be integrated into the global media economy:

- World factory/outsourcing model, where the attractions of a particular production location are almost exclusively cost-driven (and, in the case of film, elements of the ‘look’ of an area), and where investment in the city or region is largely based upon a fly-in/fly-out model, with no retention of intellectual property rights and no reinvestment into the local sectors;

- Isomorphism and cloning, where imitation of global media formats becomes the sincerest form of flattery, and where predominantly US-based media formats are either directly copied without attribution of intellectual property rights, or local variants are developed with limited alteration;

- Cultural technology transfer, whereby the interaction between international investors and local capital, skills and talent enables the development of joint ventures which provide a springboard to local industry development through technology and – perhaps more importantly – knowledge transfer, through successful adaptation and ‘modelling’ (Braithwaite & Drahos, 2002);

- Niche markets and global hits, whereby the correlation between globalisation and ‘localization’ is successfully exploited, so that media producers can benefit from a mix of regional sub-markets, identity-based sub-markets, an appeal to geographically dispersed diasporic communities, and niche markets within major global centres, as seen with the regional and global flows of music from some African countries (UNCTAD, 2008);

- Cultural/industrial milieux or creative clusters, where “the value of agglomeration is competitive advantage” (Keane, 2006, p. xxx), arising from an interconnection of local creativity, international finance, a growing talent base attracted by the success of the city or region, supportive local industries and educational and training institutions, and links to related service industries, such as advertising and financial services. Such ‘creative clusters’ or ‘media capitals’ will typically service international rather than purely local or national markets, as they become a hub for media flows across geographical boundaries (Curtin, 2003).

In drawing together these competing propositions, we can observe that more media production is being out-sourced, reflecting the combination of ‘push’ factors such as rising costs in global production centres such as Hollywood, and ‘pull’ factors such as competition among a range of international media production centres for foreign investment, often leading to a variety of subsidies being offered to would-be foreign producers. In those approaches that see offshore media production as simply maintaining relations of dominance between the centre and the periphery, these international studios lack the ‘stickiness’ to keep mobile international capital there after the low-cost productions have occurred; as a result, little or no knowledge transfer occurs. By contrast, Christopherson (2002) has argued that the emergence of such ‘routine production locations’ marks the early stages of development of global production networks in film and television production, where such relation are less likely to be one-off and more likely to be ongoing.

I would argue that because globalising trends in media production require a recognition that ‘media always involve a rescaling of territory’ (Couldry, 2007: 248), globalisation as metaphor retains some conceptual utility as it allows for an understanding of multi-scalar tendencies in both media production and consumption. At the same time, empirical work into such developments is not helped by the assumptions surrounding globalisation as a scalar shift associated with arguments that a global space of flows has displaced national media cultures and that ‘placeless’ multinational capital has undermined the sovereignty of nation-states and the relationship of territory to culture and economic organization. A more relational conception of intersections between the local, the national and the global is required to understand not only trends in media consumption and media culture, but also those of media production and the expansionary strategies of large media corporations, and it has been argued in this paper that cultural and economic geography offer important conceptual resources for such ongoing research work.

References

Amin, A. (2001). Globalisation: Geographical Aspects. In N. J. Smelser and P. B.

Baltes (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 6271–6277). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Amin, A. (2002). Spatialities of Globalisation. Environment and Planning A 34, 385-399.

Barber, B. (2000). Jihad versus McWorld. In F. Lechner and J. Boli (eds.) The Globalisation Reader (pp. 21-26). Oxford: Blackwell.

Barber, B. (2003). Fear’s Empire: War, Terrorism and Democracy. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Barker, C. (1997). Global Television: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Baudrillard, J. (1990). The Masses: The Implosion of the Social in the Media. In M. Poster (ed.), Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings (pp. 207-219). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Castells, M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. Volume 1 of The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

Castells, M. (2000). End of Millennium. Volume 3 of The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chenoweth, N. (2002). Virtual Murdoch: Reality Wars on the Information Highway. London: Vintage.

Christopherson, S. (2002). Why do National Labor Market Practices Continue to Diverge in the Global Economy? The “Missing Link” of Investment Rules. Economic Geographer 78, 1-20.

Couldry, N. (2007). Researching Media Internationalisation: Comparative Media Research As If We Really Meant It. Global Media and Communication 3, 247-250.

Crotty, J., Epstein, G., and Kelly, P. (1998). Multinational Corporations in the Neo-Liberal Regime. In D. Baker, G. Epstein and R. Pollin (eds.), Globalisation and Progressive Economic Policy (pp. 117-143). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Curran, J. and Park, M.-J. (2000). Beyond Globalisation Theory. In J. Curran and M.-J. Park (eds.) Dewesternizing Media Studies (pp. 3-21). London: Routledge.

Curtin, M. (2003). Media Capital: Towards the Study of Spatial Flows. International Journal of Cultural Studies 6, 202-228.

Curtin, M. (2004). Media Capitals: Cultural Geographies of Global TV. In L. Spigel and J. Olsson (eds.), Television after TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition (pp. 270-302). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Curtin, M. (2005). Murdoch’s Dilemma, or “What’s the Price of TV in China”? Media, Culture and Society 27, pp. 155-175.

Dajani, N. (2005). Television in the Arab East. In J. Wasko (ed.), A Companion to Television (pp. 580-601). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Dicken, P. (2003a). “Placing” Firms: Grounding the Debate on the “Global”. In J. Peck and H. W. Yeung (eds.), Remaking the Global Economy (pp. 27-44). London: Sage.

Dicken, P. (2003b). Global Shift: Reshaping the Global Economic Map in the 21st Century. London: Sage.

Doremus, P., Keller, W., Pauly, L., and Reich, S. (1998). The Myth of the Global Corporation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dover, B. (2007). Rupert Murdoch’s Adventures in China. New York: Random House.

Dunning, J. (2001a). Global Capitalism at Bay? London: Routledge.

Dunning, J. (2001b). The Key Literature on IB Activities: 1960-2000. In A. Rugman (ed.), Oxford Handbook of International Business (pp. 36-68). New York: Oxford University Press.

Ernst, D., and Kim, L. S. (2002). Global Production Networks, Knowledge Diffusion, and Local Capability Formation. Research Policy 31, 1417-1429.

Flew, T. (2005). New Media: An Introduction, 2nd Edition. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Flew, T. (2007). Understanding Global Media. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Friedman, T. (2005). The World is Flat. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Gertler, M. (2003). The Spatial Life of Things: The Real World of Practice within the Global Firm. In J. Peck and H. W. Yeung (eds.), Remaking the Global Economy (pp. 101-113). London: Sage.

Giddens, A. (1990). The Consequence of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Giddens, A. (1997). The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Giddens, A. (2002). Runaway World: How Globalisation is Reshaping our Lives, 2nd Edition. London: Profile.

Glyn, A., and Sutcliffe, B. (1999). Still Underwhelmed: Indicators of Globalisation and their Misinterpretation. Review of Radical Political Economics 31, 111-131.

Goldsmith, B.and O’Regan, T. (2005). The Film Studio: Film Production in the Global Economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Grant, P. and Wood, C. (2004). Blockbusters and Trade Wars: Popular Culture in a Globalized World. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre.

Hafez, K. (2007). The Myth of Media Globalisation. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hallin, D. and Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hardt, M. and Negri, A. (2000). Empire. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Hardt, M. and Negri, A. (2004). Multitude. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Held, D., McGrew, A., Goldblatt, D., and Perraton, J. (1999). Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Held, D. and McGrew, A. (2002). Globalisation/Anti-Globalisation. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Henderson, J., Dicken, P., Hess, M., Coe, N., and Yeung, H. W. C. (2002). Global Production Networks and the Analysis of Economic Development. Review of International Political Economy 9, 436-464.

Herman, E. S. and McChesney, R. W. (1997). The Global Media: The New Missionaries of Global Capitalism. London: Cassell.

Hirst, P. and Thompson, G. (1996). Globalisation in Question: The International Economy and the Possibilities of Governance. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Jessop, B. (2000). The Crisis of the National Spatio-Temporal Fix and the Tendential Ecological Dominance of Global Capitalism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24, 323-361.

Keane, M. (2006). Once Were Peripheral: Creating Media Capacity in East Asia. Media, Culture and Society 28, 833-855.

Kellner, D. and Best, S. (1997). The Postmodern Turn. New York: Guildford Press.

Legrain, P. (2002). Open World: The Truth about Globalisation. London: Abacus.

Lloyd, C. (2000). Globalisation: Beyond the Ultra-Modernist Narrative to a Critical Realist Perspective on Geopolitics in the Cyber Age. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24, 258-273.

McDonald, A. (2006). Through the Looking Glass: Runaway Production and “Hollywood Economics”. Social Science Research Network published paper. Available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=929586. Accessed 1 September, 2008.

McGuigan, J. (2005). Neo-Liberalism, Culture and Policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy 11, 229-241.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: Mentor Books.

Miller, T., Govil, N., McMurria, J., and Maxwell, R. (2001). Global Hollywood. London: BFI Publishing.

Nordenstreng, K. and Varis, T. (1974). Television Traffic: A One-Way Street?. Paris: UNESCO.

Perraton, J. and Clift, B. (eds.) (2004). Where are National Capitalisms Now? Basingtoke: Palgrave.

Rohm, W. G. (2002). The Murdoch Mission The Digital Transformation of a Media Empire. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Rugman, A. (2000). The End of Globalisation. London: Random House.

Rugman, A. and Verbeke, A. (2001). Location, Competitiveness, and the Multinational Enterprise. In A. Rugman (ed.), Oxford Handbook of International Business (pp. 150-178). New York: Oxford University Press.

Scholte, J. A. (2000). Globalisation: A Critical Introduction. Houndsmills: Macmillan.

Scholte, J. A. (2005). The Sources of Neo-Liberal Globalisation. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Overarching Concerns Paper No. 8. Geneva: UNRISD.

Scott, A. J. (2004). Cultural-Products Industries and Urban Economic Development: Prospects for Growth and Market Contestation in Global Context. Urban Affairs Review 39, 461-490.

Sepstrup, P. (1989). Research into International Television Flows: A Methodological Contribution. European Journal of Communication 4, 393-407.

Shawcross, W. (1992). Rupert Murdoch: Ringmaster of the Information Circus. London: Chatto & Windus.

Sinclair, J. (2004). Globalisation, Supranational Institutions, and Media. In J. Downing, D. McQuail, P. Schelsinger and E. Wartella (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Media Studies (pp. 65-82). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Sinclair, J. 2005. Latin American Commerical Television: “Primitive Capitalism”. In J. Wasko (ed.), A Companion to Television (pp. 503-520). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Sparks, C. (2007). What’s Wrong with Globalisation? Global Media and Communication 3, 133-155.

Steger, M. (2003). Globalisation: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Storper, M. (1997). The Regional World. London: Guildford Press.

Storper, M. (2000). Geography and Knowledge Flows: An Industrial Geographer’s Perspective. In J. Dunning (ed.), Regions, Globalisation and the Knowledge-Based Economy (pp. 42-62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Straubhaar, J. (1997). Distinguishing the Global, Regional and National Levels of World Television. In A. Sreberny-Mohammadi, D. Winseck, J. McKenna and O. Boyd-Barrett (eds.), Media in Global Context: A Reader (pp. 284-298). London: Arnold.

Straubhaar, J. (2001). Brazil: The Role of the State in World Television. In N. Morris and S. Waisbord (eds.), Media and Globalisation: Bringing the State Back In (pp. 133-153). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Sussman, G. (2007). Covering Eastern European and Russian Elections: The US Media’s Double Standard. Global Media and Communication 3, 356-361.

Thomas, A. O. (2005). Imagi-Nations and Borderless Television: Media, Culture and Politics in Asia. New Delhi: Sage.

Thomas, A. O. (2006). Transnational Media and Contoured Markets: Redefining Asian Television and Advertising. New Delhi: Sage.

Tomlinson, J. (2003). The Agenda of Globalisation. New Formations 50, 10-21.

Tracey, M. (1988). Popular Culture and the Economics of Global Television. Intermedia 16, 53-69.

Tunstall, J. (2007). The Media were American: US Mass Media in Decline. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

United Nations Commission on Trade, Aid and Development (UNCTAD). (2006). World Investment Report 2006. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

United Nations Commission on Trade, Aid and Development (UNCTAD). (2007). World Investment Report 2007. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

United Nations Commission on Trade, Aid and Development (UNCTAD). (2008). Creative Economy Report 2008. Geneva: United Nations.

Varis, T. (1984). International Flow of Television Programmes. Journal of Communication 34, 143-152.

Waisbord, S. (2000). Media in South America: Between the Rock of the State and the Had Place of the Market In J. Curran and M.-J. Park (eds.), Dewesternizing Media Studies (pp. 50-62). London: Routledge.

Wang, J. (2008). Brand New China: Advertising, Media, and Commercial Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wasko, J. (2001). Understanding Disney. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Waters, M. (1995). Globalisation. London: Routledge.

Weiss, L. (1999). Globalisation and National Governance: Antimonies or Interdependence? In M. Cox, K. Booth and T. Dunne (eds.), The Interregnum: Controversies in World Politics 1989-1999 (pp. 59-88). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weiss, L. (2003). Is the State being “Transformed” by Globalisation?’ In L. Weiss (ed.), States in the Global Economy: Bringing Domestic Institutions Back In (pp. 293-316). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yusuf, S. (2003). Innovative East Asia: The Future of Growth. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Zayani, M. (ed.) (2005). The Al Jazeera Phenomenon: Critical Perspectives on New Arab Media. London: Pluto Press.

Zhao, Y. and Guo, Z. (2005). Television in China: History, Political Economy, and Ideology. In J. Wasko (ed.), A Companion to Television (pp. 521-539). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Figure 1

Foreign Direct Investment by Type of Economy – Developed and Developing, 1980-2005

About the Author

Terry Flew is Professor of Media and Communication in the Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology. He is the author of New Media: An Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2008, Third Edition) and Understanding Global Media (Palgrave, 2007). He is the author of 29 book chapters and 42 refereed journal articles. Professor Flew is President-elect of the Australian and New Zealand Communications Association. He is a Chief Investigator with the ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation and a member of the Cultural Research Network.

Contact Details

E-mail: t.flew@qut.edu.au