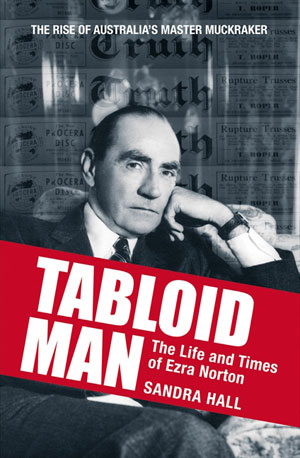

Hall, Sandra - Tabloid Man: The Life and Times of Ezra Norton, Harper Collins Australia, Sydney, 2008, (pp335) ISBN 978 0 7322 8259 2

Hall, Sandra - Tabloid Man: The Life and Times of Ezra Norton, Harper Collins Australia, Sydney, 2008, (pp335) ISBN 978 0 7322 8259 2

It is disconcerting that this biography, sub-titled The Rise of Australia’s Master Muckraker left the reviewer feeling nostalgic about the “good old days” of Australian journalism.

Of course, whether the old days were “good” is a question of definition and while Sandra Hall’s biography is a rollicking good read, that’s not the source of the nostalgia. Many of the things that happened on Ezra Norton’s watch between 1920 and 1958 were nothing to be proud of - unethical, illegal and unseemly. And he didn’t hesitate to use his titles to pursue his greatest rival, Frank Packer.

Both he and Packer were old-fashioned media megalomaniacs, transparently pursuing their media interests for personal profit and political power. Somehow today that seems to have more journalistic integrity than media decisions based on profitability for shareholders who don’t care about content at all.

The first part of Hall’s biography necessarily considers the life of his father, John, the charismatic, scandalous, violent alcoholic who used the front pages of his newspapers to pursue his own messy divorce. Cyril Pearl chronicled some of these excesses in Wild Men of Sydney (1958:7) where he described the editors of the day.

They were aggressive and accomplished demagogues who made little or no attempt to conceal their complex villainies. But the frequent exposure to these villainies served only to consolidate their position as public heroes.

John Norton’s public excesses had a sobering effect on his son, who preferred no publicity at all (p.279), but Ezra was very much his father’s son when it came to the newspaper business. It was a business he pursued avidly his whole life, before unwittingly relinquishing the baton to a young Rupert Murdoch in 1958. And while Ezra was a teetotaller, he lived up to the definition of the “larrikin” newspaperman by his paper’s defiant support of the working-man when he inherited the Truth at 23. Norton’s heyday, between the first and second World Wars, was a lively and highly competitive time for “People’s Papers”. Yet as Hall (p136) notes:

Despite the robustness of the competition, Truth was doing well with its gamey mix of crime, divorce, sex, sport and a slightly more measured and pragmatic form of populism than the old John Norton brand.

Norton’s paper reflected his view of the world, his preoccupations. Truth was concerned with exposing medical quackery, obsessed with hygiene and abhorred animal cruelty. It was also a staunch defender of the White Australia policy, but deplored the Ku Klux Klan.

He stood up for his employees in the courts, defending the refusal to reveal sources, but was universally feared for the “boning-and-gutting sessions” that came with his displeasure. He pursued vendettas through his publications, famously setting his sights on the NSW Police Commissioner McKay in 1936 after he disciplined a constable who blew the whistle on a colleague’s corrupt conduct. Norton hired a leading barrister to represent the constable and set about personally attacking the Commissioner in his papers.

His greatest fight, however was reserved for the legendary rivalry with Frank Packer fought in the pages of the Daily Telegraph and The Truth and later the Telegraph and the Daily Mirror. Norton later sold the Mirror to a young Rupert Murdoch and Hall notes there is little doubt he regretted the loss of his newspapers.

Sandra Hall is an accomplished journalist and her biography is as entertaining as it is easy to read. She reminds us that the urge to express and provoke outrage that defined Norton’s era is still a driving force in today’s popular media. The difference is that today the decisions about what to support and what to decry aren’t made by “go-it-alone” larrikins like Norton. Instead, editors must ensure that that their targets are also abhorred by their carefully researched readership and are acceptable to shareholders.

That’s what made Tabloid Man such a nostalgic read for this reviewer – it harks back to a time when journalists were noisy dissenters who poked fun at authority and were outraged on behalf the “little man”. Journalism wasn’t a profession then but it was a vocation.

About the Author

Professor Lynette Sheridan Burns is the Head of the School of Communication Arts, University of Western Sydney. She has been a journalist for 25 years in Sydney then regional New South Wales. Professor Burns is the author of Understanding Journalism (Sage: 2002).