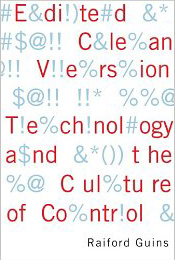

Guins, Raiford - Edited Clean Version - Technology and the Culture of Control

Guins, Raiford - Edited Clean Version - Technology and the Culture of Control

University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis/London, 2009 (pp.280)

ISBN 978-0-8166-4815-3

Have we fallen into a trap of paying for the privilege of lesser products? In Edited Clean Version, Raiford Guins demonstrates how today’s media technology is marketed and sold for what it does not contain and what it will not deliver. The Assistant Professor of digital cultural studies in the Department of Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies and Consortium for Digital Arts, Culture, and Technology at SUNY Stony Brook, argues that consumers now find themselves in new relationships with their everyday media in which they inscribe their viewing, listening, and playing experiences with self-prescribed and technologically enabled values and morals.

While Australian readers will at times distance themselves somewhat from this US-centric study – in America the V-chip, a technological ‘solution’ for policing television content reinvigorated by networks, politicians and media watchdog groups after Janet Jackson’s ‘wardrobe malfunction’ revealed a breast during her half time performance at Super Bowl XXXVIII in 2004, is now required by law to be built into every television – the book’s censorship themes resonate.

The themes are interesting and relevant considerations when we consider that traditional classification systems no longer work. Such systems are premised on the assumption that by regulating distribution, importation and exhibition of material, what people are able to view, read and experience can be controlled. This is of course no longer true. Books, films, images and games can be ordered from anywhere in the world through iTunes, Amazon, eBay or millions of other sites and services, and sent by mail or downloaded directly onto computers and other personal devices.

Guins argues that censorial practices are not so much enacted on media by regulatory bodies – they are now in media technologies. According to Guins, these new ‘control technologies’ are designed to embody an ethos of neo-liberal governance through the very media that have been previously presumed to warrant management, legislation, and policing. Repositioned within a discourse of empowerment, security, and choice, the action of regulation, he reveals, has been relocated into the hands of users.

This cultural study of the ways that censorship has evolved in the multimedia era, is a scholarly look at the culture of editing works of art. Today’s DVD player, game console, television and computer, can block out, monitor, disable and filter online information, digital television transmissions and pre-recorded media according to a ‘parental function’ designed in the hardware or available as software. Over six chapters, Guins talks about a separate type of editing: from controlling content, to blocking it, filtering it, sanitising it, cleaning it, and finally patching the content.

Guins points out that with the advent of new technology, censorship that was the responsibility of regulatory bodies is now in the hands of those whose ability to censor is neatly packaged within the TVs, DVD and CD players, and game consoles we buy and bring home. He argues that because electronics are now outfitted with V-chips, Internet filters, and parental controls, consumers can now adjust their viewing and listening patterns to suit their own values and morals, and traces the development and implementation of the technology and its implications. This is, he argues, distinct from “but also a reinforcement of the ‘family entertainment’ policies of long-standing institutions commonly associated with film censorship and classificatory practices.” (p. xiii) As Honey Whitlock (Melanie Griffith) says in the film Cecil B. DeMented (John Waters 2000), “family is just another word for censorship!”

The book is not declaring the end of media censorship, says Guins, but rather attempts to grasp a new beginning in its intensification. He discusses the increasing difficulty of maintaining a medium-specific approach for the study of media censorship and working within the disciplinary borders that claim a medium. This emergent formation of power, as well as our own conceptual uncertainty in articulating these power relations, “bears immediate attention in order to excogitate the governing of culture within the US and in our digital present” (p. xiv).

Guins notes his use of the entry point many others have taken for positioning media technology within the study of culture and governance: Gilles Deleuze’s brief work on ‘control’. Chapter 1 familiarises readers with Deleuze’s notion of control and writing on governing that extends to Foucault’s work on governmentality. The chapters are then organised according to operations of control as Guins argues that new freedoms of control operate through a constant management of ideological positions that attempt to engineer concepts such as family, domesticity and security through definitive proclamations on media.

Chapter 2, “Blocking”, identifies this process with the V chip. Chapter 3 furthers the discussion by engaging with the Internet and networked computers and looks at computer software that blocks, filters and monitors web content in the forms of ‘parental controls’. Chapter 4 locates the process in the videocassette, DVD, DVD player and the technology of the video store: it attends to the practice of re-editing Hollywood copyrighted films to remove footage and dialogue deemed obscene by US companies Clean Flicks and ClearPlay. He discusses how the ideological, religious and political biases that come to substantiate family-friendly media according to these companies, are left intact. For example in Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down (2001), the family audience is spared from seeing bullets penetrating the bodies of US soldiers while the deaths of Somalis are left intact. Chapter 5 concentrates on digital special effects as censorial practices in film and music.

As we have seen in recently in Australia regarding, to name two examples, the Bill Henson photography case and the proposal for a national Internet filter, any analysis of censorship issues are often precluded by high-minded rhetoric and simplistic solutions. “Our media are now machines for protection, security and resolution. Not restrictive, but freeing … Control technologies are mediators of neo-liberal governmentality” (p. 170-1).

The book is interesting reading in light of the Australian government’s internet censorship plan (the announcement of which was followed by online outrage via Twitter and other social media). Any plan seems wrought by inefficacy, but the rationale behind such an initiative is also suspect: what exactly should be censored and by whom? And what is meant by the term “Refused Classification”? A report by professors Lumby, Hartley and Green, for example, found that Refused Classification includes material such as education content on drug use and euthanasia due to the social controversy about such issues. Ultimately, the government should not have the right to block any information that has potential to inform public debate.

About the Author

Dr. Milissa Deitz is a journalist and author who teaches media and communications at the University Of Western Sydney.