Google Earth and the Business of Compassion

Google Earth and the Business of Compassion

Politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and the possibilities of time (Jacques Rancière 2004: 13).

Google Earth is a culmination of remote sensing satellite technologies, mega database and 3D animation: a tool for militarised vision and also a tool for an embodied compassionate vision – in Caroline Bassett’s words, for “love at a distance” (2006: 201). This paper focuses on Rancière’s above quoted idea of the relation between politics and “the ability to see” embedded in “properties of spaces and the possibilities of time”: three elements integral to new visions of the world enabled by Google Earth.

As Roger Stahl notes, “the geopolitical significance of Google Earth can be approached from at least two directions... [as] a ‘metaregime’ of visibility…” with the second perspective operating via “the ‘aesthetics of visibility” or the ways Google Earth acts as a kind of text, a powerful public screen onto which a political landscape is projected and thereby made sensible” (2010: 67).

The discussion in this paper addresses Stahl’s latter perspective and argues that one of the hermeneutic responses available to a text such as Google Earth can be named, in philosophical terms, as the emotion of ‘compassion’. I am drawing on Martha Nussbaum’s understanding of compassion as a “thought experiment” and as a good will towards others’ well-being. Compassion, then, is an emotion-driven imagination that draws on a person’s own life experience to identify with and, to an extent, feel another’s situation (Nussbaum, 1996: 48).

I argue that such an approach is valid because it adds to our knowledge of how the ‘political landscape’ of such a widely accessible text as Google Earth is understood by people using it as an individualised point of access to the world. My methodology is textual analysis, based in the self-reflexive tradition of hermeneutics. In Gadamer’s words, a text is “that which resists integration in experience and represents the return to the supposed given that would then provide a better orientation for understanding” (1986: 389).

My interpretation of Google Earth as text emphasises the word ‘resists’ in this quote. The images derived from Google Earth are the sites of interpretation – Gadamer’s “supposed given” – the images of Google Earth ‘resist’ the experience of immediacy due to their changing contexts of visualised time and space. Yet, at the same time, the sites of interpretation offered by Google Earth demand a new consideration of the ways in which the illusion of direct experience, the sense of personalised contact in a particular time and space, works. Google Earth draws us into an imagined space of contact with the people and places it represents. This imagined space of contact is, nevertheless, embodied via the very mechanisms that provoke our perceptual immersion.

The concrete interactivity involved in accessing Google Earth via a computer is clearly the primary trigger for such immersions that also depend, as do all receptive experiences, on the cognitive interaction between images and our personalised histories and memories. This paper closely describes one particular kind of the response to the real world made available via Google Earth. I propose that this response can be defined as compassion and that it constitutes a particular “ability to see”, one of the processes whereby we understand the complex textual instances found in Google Earth. The particular sub-text of Google Earth that I am using for this analysis is “Crisis in Darfur”, this is a collaboration between the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) and Google Earth.

Through focusing on the site “Crisis in Darfur” this paper examines the question: does the way we interact with Google Earth offer a new pathway for compassion? My discussion focuses on one of this site’s Global Awareness Layers: “Crisis in Darfur” – not a place for leisurely respite of any kind but one which presents the horrors of what many claim to be a recent genocide. I suggest that the Google Earth site of “Crisis in Darfur”, constructed in collaboration with the United States Holocaust Memorial Center, offers an opportunity to appraise a new conjunction of those who see and those whom are seen.

In her landmark essay “Digging into Google Earth: An analysis of ‘Crisis in Darfur’” (2009) Lisa Parks notes that,

… few have considered how Google Earth builds upon and differs from earlier global media formats and how it structures geopolitics as a “domain of affect”, particularly when used as a technology of humanitarian intervention (2009: 3).

Whereas Parks goes on to situate her own investigation into Global Earth firmly within the sphere of geopolitics, I focus on the ramifications of Google Earth as an interactive technology for eliciting one specific response to “Crisis in Darfur” compassion.

Before introducing Google Earth itself, it is useful to look, briefly, at the digital media culture from which this site emerged in 2005, a culture that describes communication undertaken via the web as happening in ‘virtual’ space. Prior to the emergence and cultural dominance of the major social networking sites of Facebook and, especially, of YouTube in 2005, virtual space held the same kind of numinosity as William Gibson’s ‘cyberspace’ (1984) – an alternate reality.

Be it magical, terrible or desired escapism, the meaning of the word ‘virtual’ implied a separate space of existence more related to imagined worlds than the ‘live’ worlds of mundane human existence. The Social Web, Web 2.0, introduced not only new digital platforms for networking and community formation; it also heralded the arrival of a young generation of users who have grown up with these websites. I suggest that distinctions between the ‘virtual’ and the ‘real’ world have become just about irrelevant, except perhaps in the realm of gaming; and even in this sphere of play, the uses of gaming and their simulations and the impact they have on players in the ‘real’ world is acknowledged as a part of gaming culture itself.1

Anna Munster conceptualises the idea of the ‘virtual’ as “a set of potential movements produced by forces that differentially work through matter, resulting in the actualisation of that matter under local conditions” (2006: 90). I am interested in this “actualisation of that matter under local conditions” that Munster says is implied by the use of this term ‘virtual’ and how it comes about in experiencing Google Earth. The following discussion focuses, to use Donna Haraway’s words, on how the “‘eyes’ made available in modern technological sciences shatter any idea of passive vision …” (1991: 190) and how the sense of vision, or looking, with these new kinds of eyes, can invoke a kind of agency that is not perhaps overtly political.

The interactivity between human and machine required to use Google Earth, is aggressive in the sense that it has purpose. It is not possible however, to clearly differentiate between various motivations that might lie behind a particular instance of accessing Google Earth. These motivations can include an open curiosity, a more focused curiosity aimed at finding certain sites. In turn, such curiosity can be derived from a morally positive or negative point of view. Constructive action towards the well-being of another individual can be an outcome of searching Google Earth, but this of course is only one possible outcome amongst many others.2

The current world of interactive digital environments demands from us a high level of digital literacy. If we are to use them in order to exert political agency of any kind, such literacy includes the understanding of the ‘virtual flyby’ sensation which developed from ‘first person shooter’ games that still offer a banal yet enticing sense of power, freedom and visceral delight, to games that combine live action sequences, complex, and interactive storylines.

Roger Stahl thoughtfully describes Global Earth in the context of its history and the resulting geopolitics of militaristic “virtual flyby” aesthetics are inherent in “first person shooter” styled games (2009: 67). He focuses his investigation on how Google Earth acts “as a kind of text, a powerful public screen onto which a political landscape is projected and thereby made sensible” (ibid). Whereas Stahl is concerned with the tension between agency and geopolitical forces, with “what narratives are recalled in the image, and how weaving the technology into existent cultural practices plays a part in conditioning the meaning of geopolitical relations …” Stahl’s paper and my own nevertheless share a joint interest in “how the Google Earth aesthetic has evolved to become a part of public consciousness” (ibid).

The simultaneous playful delight of flying and looking, and yet also finding out ‘serious’ information, is the common experience of this Google Earth; “virtual flyby” aesthetics becomes not only the domain of institutionalised, militarised reportage, but also the domain of purposeful individual imagination and understanding.

Google Earth

Google Earth: a site for playful fun, for the getting of information about the world and also a site of serious play. Google Earth is a widely accessible communication space that uses the documentary-styled rhetoric of non-fiction, the archiving of texts and images in time and, most remarkably, a sense of space.

|

Stahl’s (2009) and Parks’ (2009) essays provide invaluable material for discussing the sometime bizarre tensions that exist between the banal and the profound in manifestations of trauma to be found in both the production, history and content manifested in Google Earth. Such tensions are illustrated by the Google Earth’s representation of Southern Sudan where one can not only find the “Crisis in Darfur” site, but also an icon that links to a video clip of photographs matched to Michael Jackson’s song ‘We Are the World’.

The corporation Google.com adopts a policy of providing information about itself and its related activities within its own web pages and accordingly provides its own history and vital statistics via its own homepage link to “Corporate Information” (Google, online). Through this site, we learn that in 2004, Google acquires Keyhole, “a digital mapping company whose technology will later become Google Earth” (Google Earth, online). Google Earth itself was launched in June 2005. In August of the same year, Hurricane Katrina hit the southern states of the US.

This use of Google Earth inspired the development of a permanent feature on the site called Global Awareness 3. The most elaborate layer is “Crisis in Darfur”, which was launched in 2007. This collaboration between Google and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) was initiated by the Museum and was undertaken to present a complex, multi-layered web documentation of the massacres, massive displacement of people, and the destruction of villages occurring in Darfur as a result of the civil war in the Sudan. To quote the Google Press Center itself:

… more than 200 million Google Earth™ mapping service users worldwide to visualize and better understand the genocide currently unfolding in Darfur. The Museum has assembled content – photographs, data and eyewitness testimony –from a number of sources that are brought together for the first time in Google Earth (Google Press Centre, online).

The information derived from this layer is regularly updated, as evidence in the link to the USHMM Mapping Initiative page shows: http://www.ushmm.org/maps/ (accessed 14/9/2010). Currently, there are sixteen Global Awareness Layers, including a link to the USHMM “World is Witness” layer, which is used to trace other such places of grief and horror such as Rwanda, Bosnia and more recently, the war in the DR Congo.

The USHMM site itself is available via Google Earth and is a complex one, containing a lot of information about conflicts, which is made available via a surfing of hyperlinks. As with most web surfing experiences, it is easy to lose one’s way as you burrow further into the maze of images and text to find even more information. The following link is to a page in the USHMM site, which describes some of the ongoing history of civil war in the Sudan: http://www.ushmm.org/genocide/take_action/atrisk/region/sudan.

The site “Crisis in Darfur” is based on the conflicts and human rights abuses resulting from the most recent episode of civil war that began in 1983. I want now to discuss how accessing information via Google Earth about such a conflict can construct a particular kind of knowledge.

An interactive aesthetic

Before describing the Global Awareness Layer of “Crisis in Darfur” site in more detail, I will describe a particular kind of experiential knowledge which might be enabled through an individual navigation of Google Earth and which I suggest forecasts the experience of “Crisis in Darfur” as a likely site for evoking a compassionate response. As discussed above, Stahl describes the viewing position interpolated by Google Earth as having some of the attributes of a “first person shooter” computer game. These attributes include the sense of surveillance, of being the eye behind a camera, which cruises above the earth and can zoom down and across to view more closely places chosen for interest and curiosity. When using this platform there is certainly a sense of computer game playing, as noted by Stahl.

This particular “game-styled” playing of Google Earth, however, is not driven only by the position of the “first person shooter”; it is also a world-building game.4 We are able to build a world visualised through our own searches for information – a beautiful world consisting of actual images of the earth annotated by spatial and time co-ordinates, and animated for different viewing styles if we wish. Nevertheless, this description of likeness between the experience of Google Earth and computer game playing does not, per se, equate the platform with a gaming platform. It does, however, offer an understanding as to how personalised, so-called ‘virtual’ worlds are offered to, and constructed by, the user in collaboration with Google Earth.

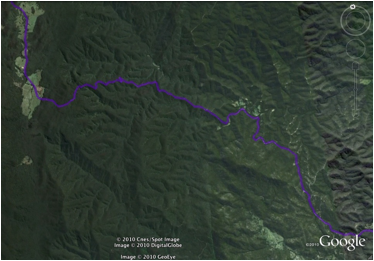

We interact with Google Earth in ways already available to us through and to the extent of our digital literacy. Such attributes of interactive ‘playing’ are certainly associated with the immersive nature of the environments that we create when ‘searching’ – thereby creating a sense of place and time during our individual, usually private, uses of Google Earth. I suggest that the problem of representing the subjective experience that emerges from immersion in such an interactive site as Google Earth can be addressed by the process of “thick description” of individual experiences. As an example, I am now going to make one of my own Google Earth journeys public: “Driving to the coast from Canberra via Braidwood (Australia)”.

A New Kind of Journey: ‘Flying through space above the earth, around the world’

I am describing here my own experience in personal, highly descriptive terms, in “diary mode”.

This particular road is full of hairpin turns, down a mountain and on to the sea at Batemans Bay, NSW. I spend as much time as I can “down the coast” and I associate the landscapes of both the car trip and the coast with leisure and pleasure. But I do not like this trip itself if I am driving. I find my negotiations of other traffic and the contours of the road make it a difficult drive.

Last year, I decided to see how this road looked when viewed from above. I wanted to see why I found the road difficult to drive – I wanted to see its shape and therefore somehow to own it, to understand it differently and not just have to put up with my own very limited imagination. I used Google Earth to look at how this wretched road looked from the sky. I was, and still am, able to achieve this journey on Google Earth via my computer mouse and the navigational device – a compass overlay that I can also use to increase or decrease my speed.

|

Suddenly, I have a new driving skill: “driving the mouse in Google Earth”, not quite as tricky as driving a car but now it feels like I am more in control – sort of, I tend to veer on and off the road into forested wilderness, but at least I can understand through my own mouse driving mistakes some of the problems in engineering this road. Now I can see the beginning and the end – the beginning and the destination of my journey.

In his essay “Tabula Rasa”, Paul Virilio quotes Walter Benjamin on what Benjamin calls the ‘force’ of the road:

The force of a country road differs depending on whether you are doing it on foot or flying over it in a plane. Only when you are travelling along the road can you learn something about its force (Benjamin cited in Virilio, 2005, 2007: 2).

Now with Google Earth, I can experience another kind of force of this particular road, or perhaps, I can expand my experience of ‘Benjaminian’ force through manually tracing the road over terrain I could not see from the car.

How to analyse this experience? Here I can draw again on Benjamin, whose words well and truly pre-date Google Earth but who spoke of changes in perception arising from new technologies. For example, Benjamin’s idea of ‘shock’ evoked by the close up images of cinema and the chaos of industrialised cities has direct relevance in the sense that Google Earth makes possible a utopian but sensual perception of times and places in the world that are hitherto unfamiliar. My own personally constructed journey of the Braidwood coast road led to another one journey, this time losing and finding my way across the earth to Africa – recalling another quote from Benjamin in Virilio’s essay:

Not to find one’s way around a city does not mean much. But to lose one’s way in a city, as one loses one’s way in a forest, requires some schooling (Benjamin cited in Virilio, 2005, 2007: 1).

My ‘driving’ journey was my first time use of Google Earth. I followed up with a look around the rest of the world (Benjamin’s city?), as we do when the opportunity arises … and I found Darfur, marked with icons of flame, cameras, words and filmmaking.

“Crisis in Darfur” is not an easy site to access: its icons overlap and relay a sense of confusion - of chaos even - and so create a gesture of searching indicative of the situation represented: one of war and displacement.

|

After exploring this site as best I could, I thought about the conjunction of my ‘virtual’ personal, domestic journey in my own homeland and the journey I took across to Africa shortly afterwards. The following questions arose: did each of these journeys imply an inherent way of knowing the other? In other words, was I able to transfer the sense of immediacy in time and space that I felt in my journey to the coast to my confrontations with the agonies shown in “Crisis in Darfur”? This question is unanswerable in a literal sense. I suggest however that the question itself provides another kind of answer. It describes and speculates on how we can respond to Google Earth in the context of feeling and emotion.

Affective knowledge and the flames of Darfur

Can we understand Google Earth, then, as a site that can elicit the experience of ‘knowing’ with compassion previously unknown to people? This is not a question about “soft arm chair activism” and its relation to voyeurism; it is an inquiry into whether or not a certain kind of affective experience, derived from an interactive aesthetic, can be described as one that is socially useful and, to a degree, necessary for further political action. This question, in turn, requires a consideration of compassion as an active state of “knowledge [which] is based on embodied subjectivity and that this form of knowledge is action” (Marmor, 2008: 322).

The following quote is from Kathy Mamor’s discussion of Steven Holloway’s 2005 performance One Pixel: An Act of Kindness:

If knowledge is the capacity for action, then there must also exist power … When these two conditions are met, then there exists the possibility of agency (2008: 323).

Mamor’s words are important in relation to thinking about engaging with the aesthetic of Google Earth, both with its offerings of knowledge enhanced through the sensation of flight and with the images that Google Earth makes available through its Global Awareness Layers. Due to the nature of experiencing the particular aesthetic of Google Earth, there is an inherent sense of power/agency and a fairly immediate sense of acting out this power at an individual level.

Yes, we can pick up a pen or Visa card and donate to one of the organizations contributing to these Global Awareness Layers – this is one of the more overt manifestations of agency in relation to the knowledge acquired from accessing these and related sites. However, I suggest there is another primary agency involved with the actual acquisition of such knowledge. I suggest that our investigative engagement with Google Earth can actually constitute a political engagement.

The morality of this engagement is another matter. While I will not be discussing, in any detail, the actual possibilities (or lack of them) regarding specific capacities for action, as noted before, I do suggest that by understanding the practice of compassion as an active kind of knowledge, we can also describe a particular kind of knowledge that emerges out of our own personalised navigations of Google Earth.

I will take up this discussion again shortly. But note here that more banal actions can range from the simple one of giving money to an activist organisation, working for an activist organisation, offering comment on the activities of an organisation and the people they represent in other media or joining in dialogue with other people about the debates raised by information offered on such sites.

Sam Gregory, from the human rights activist organisation Witness.Org http://www.witness.org, notes that the overall action that eventuates in finding such sites as Google Earth’s “Crisis in Darfur” could well be described as one that “stumbles upon” (personal communication, 2010) something that can surprise and/or satisfy a search for something unknown.

This act of ‘stumbling’ on information via the web also describes well the nature of ‘surfing the web’. In the case of Google Earth however, ‘surfing’ is achieved via a very particular aesthetic, one that induces a sense of hovering over a world which is both familiar and yet made strange. In the sense of Russian Formalism’s idea of ‘oestranenie’, through the novel, carries an embodied sense of combined visual pleasure and weightlessness in flight, in Fredric Jameson’s words, through “a renewal of perception” (1972: 51).5

Through “Crisis in Darfur”, one can gain access to stories, witness statements, photographs, statistics, and videos that are laid over/embedded in a vast topography of human destruction, with some icons introducing us to higher resolution shots of the earth, zooming across landscapes of burnt villages and refugee tent cities. These ‘close ups’ strongly emphasise a challenge that we need to confront more and more in our globally constructed perception of the world – one that we experience whenever we look out a plane window on to the landscapes of the earth beneath us.

A new kind of sociality

The challenge faced in the current moment in history is to understand how we embody our vision of the world at a distance with the people and stories that populate this world, and then how can we maintain compassion through the virtually real spaces of new media platforms?

In Sherry Turkle’s words:

[W]e are witnessing a new form of sociality in which the isolation of our physical bodies does not indicate our state of connectedness but may be its precondition (2006: 222).

Such a “new form of sociality” suggests that we must once again deal with the collision of indexicality, re-introduced by interactive surveillance platforms such as Google Earth, and the subjective states of real people: us the viewers and those we connect with in virtual space.

In this sense, the site “Crisis in Darfur”, brought to you by Google Earth, represents and documents an earth haunted by real people. As I have noted in my discussion of the interactive potential of digital spaces, this particular kind of haunting, although derived from earlier cinematic and photographic practices, nevertheless is new. In Google Earth, we can also manifest our own haunting of landscape and time. We touch our mouse, our pad, our keyboard, we trace our own journeys and those terrible ones of others. We trace them with our hands. We know the pattern of our own tracings of our own journeys. Now we trace those of others. We do this via the conjunction of cognitive processes of memory and speculation with the modeling and remote sensing technologies that comprise Google Earth. We can touch other people’s subjectivities, perhaps, touch them at a distance mediated through time, place and the interactive technologies of Google Earth. This ‘touch’ comes from our placement of their stories within our own life stories. We touch them via a dialogic engagement with the complex texts of their representations in Google Earth.

My contention is that our expanding literacy in the ways in which digital media can be used to perceive the world differently using new media offered to us, such as Google Earth. In particular, our growing intelligence in how the processes of interactivity and immersion that are inherent in the way we perceive digital images, can factor into how we interpret such explicitly interactive texts by engaging the fraught, ambiguously determined domain of how we might to be said to ‘perform’ these texts. And if we employ the trope of performance to our textual interpretations then we also must confront the possibilities of feeling and emotion, and the subsequent knowledge that these interpretations might bring us.

When exploring Google Earth via concepts of embodied aesthetics and performance, it also should be remembered that Google Earth is not simply a visual space. It contains within its various layers of “Global Awareness”, points of access to the actual sounds and voices of people and places.6 Whether or not these points of access are via digital or analog (filmic) representations is not relevant in so far as they are still representations, not actualities. It is more a matter of how Google Earth acts as a centre for distribution of these images and the contexts in which we find them, although the combination of sound with image often does indeed bring an added sense of immersion in the virtual reality of their representation.

An aesthetic of remote sensing

Because Google Earth is produced via a sense of touch at a distance, it can be thought of as a re-incarnation perhaps of the lost indexical image of photography, or at least to some of its properties of being captured at the very point of its existence in space and time. It has become a site populated with the sublime and mundane communications that are both characteristics of Web 2.0 – people can ‘place mark’ their own photographs and text to tag a particular place as important to them as individuals.

So there is a social precedent for using Google Earth as a site which can be used to mark places visible from space and that people have actually touched themselves. People can say about various places represented in Google Earth: I was here, I climbed this mountain, this was the route I took to get from here to there. Our markings are produced through a literal kind of interactivity with the site. We can tour from one place to another, forever with a ‘bird’s eye view’ of the places we have been or would like to go to. We can see the patterns of the earth as humans have actually touched it and marked it - via their own feet and vehicles, and through remote sensing.

Caroline Bassett describes this phenomenon as follows:

Remote sensing is a form of interrogation at a distance, a mode of engagement at arm’s length, but still an engagement … remote sensors make it possible to touch a surface, to interrogate it, without being in direct contact with it. This is touch at a distance … Remote sensing thus suggests profound transformations in human sense perception, part of a broader series of (technologically influenced) shifts that are having an impact not only on scientific processes, but also on everyday life (2006: 200).

Bassett goes on to say:

[P]erhaps there are correlations between remote sensing and new forms of love at a distance, not least because both processes, to some extent an art, are characterized by a certain degree of asymmetry (2006: 201).

An asymmetry between places we can see and which cannot see us, but these places can certainly touch us and so engage us and the ways we ourselves live.

For example, when we open the shades of a plane’s window, when flying over Afghanistan at 30,000 feet, we see the actual brown folding hills of this country and know at the same time that terrible conflicts of war are happening, hidden and yet marked by the topography itself. The kind of reality that is imprinted on us at these casual moments of viewing the indexical world beneath us is both easy to apprehend and yet terrifying. Google Earth, on the other hand, is a representation: a visualisation of information gained via the touch of remote sensing but nevertheless it can show us the same kind of image that we see beneath that impossibly flying plane, and it can include something more. We can humanise the spaces we see: what is hidden from us looking down at 30,000 feet can be revealed on Google Earth in such sites as “Crisis in Darfur”.

Compassion

Both experiences of ‘flight’ shake the boundaries of our physical selves, of where and how we exist in time and space. Can they shake them enough for us to encounter what Martha Nussbaum defines as compassion

in the philosophical tradition’ as “a central bridge between the individual and the community: it is conceived of as our species’ way of hooking the interests of others to our own personal goods (1996: 28).

It is the emotion of temporary identification with someone else who is suffering what they do not deserve. In discussing compassion as defined through Rousseau’s fictional character Emile, she quotes Rousseau in Emile as follows: “To see it without feeling it is not to know it.” She immediately goes on to explain, “[t]hat the suffering of others has not become a part of Emile’s cognitive repertory in such a way that it will influence his conduct, provide him with motives and expectations …” (Nussbaum, 1996: 38)

Do we need to empathise so strongly with people whom we see suffering as to feel pain ourselves? This is surely an ability few could have and probably none would want: is this ability necessary to experience compassion? Nussbaum answers this again through the narrative fiction of Rousseau’s Emile: “No such particular bodily feeling is necessary… we look for the evidence of a certain sort of thought and imagination, in what he says, and in what he does” (ibid).

Indeed, Nussbaum understands the emotion of compassion as necessary for developing knowledge of other people, both as individuals and as communities. She speaks of ‘imagination’ and I am suggesting here that our haptic, interactive ways of perceiving the images we find in “Crisis in Darfur” can provide a key into that faculty of imagination that resolves into the knowing emotion of compassion.

The artist Susan Kozel’s words well express the melding of new and older forms of responsivity and responsibility that might evoke compassion via sites like that of Google Earth:

Spontaneous compassion is not derived from axioms or rules; it arises from the demands of responsivity to the particularity and immediacy of lived situations. The virtual self, as decentered and spontaneous, performs and improvises within an underdetermined space. This sense of groundlessness wherein responsivity to the elements of a new system escapes habit and fosters new movement and ideas… (2007: 82-3).

So, love at a distance? Is this possible in the sense that love is a compassionate engagement with the ‘other’? Can we imagine such a kind of engagement with imagery across time and space, in opposition to a previous ennui of other such repetitive imaging of people, wars and places that it seems we cannot affect, that exist so far beyond our own actual experiences? Will we always simply file the information gained from these images as documentary, truth-saying information, documents to be filed so we know about them but do not have to be affected by if we choose? Post 2005 and the emergence of the culture defining sites of the Social Web, I think we can and are imagining a kind of compassionate engagement with people and places via digital imaging and imagining. We lay the foundations of this kind of experiences in our use of the web to communicate our intimate thoughts in Facebook perhaps, and in using Google Maps and Google Earth to imagine our own special, spatial fantasies of the world we live in. In this sense, then, Google Earth not only offers a touch from the world beyond our physical self, it can also, in ways different to before, make it possible for us to own the stories of people and places in this world, that exist beyond our embodied selves. How, then, can we begin to link both the idea and the possibility of our actual embodied active reception of Google Earth’s depiction of “Crisis in Darfur” to a closer description of how the experience of compassion might be elicited as a response to this site? This is a big question and one that this present paper has worked towards beginning to answer.

Parks’ comments follow on the very new rendition of satellite images into the realm of popular imaginations:

Perhaps we could imagine the satellite as generating a kind of “orbital pull”, a metaphorical dislocation, a figurative removal from the zones of security and comfort in the world, forcing us to recognize the partiality of vision and knowledge and to embrace the unknown (2005: 91).

In her even more recent writing (2010), Parks also notes that artists have led the way into how such popular imaginings and satellite imagery are currently being articulated by installation artists in both words and work, for example, my use of Bassett’s wonderful questions about remote sensing as being a possibility for “love at a distance”.

In this sense, artistic practice is subverting the surveillance/violence nexus of military practice towards a new one based on knowledge gained from interactive, haptic experience gained from a database of images from space. The interactive experience itself is not then merely to be thought of as simply accessed through satellite sponsored, remote sensing technology. These technologies are a performative part of this experience; we engage with them as we interact, even if we do this via the agendas of corporations such as Google.com.

Stahl claims that because of its history and the use of “surveillance from the sky” technologies “Google Earth has been unable to shed its martial aura” (2010: 1). This may be so, but it is not the only aura available to this site, as illustrated by its various civilian uses as personal mundane records of wanderings over the earth and as a site for the re-presentation of human rights and environmental activism. The haptic nature of the knowledge gained from a site such as “Crisis in Darfur”, the interactive combination of near and far vision given to us via Google Earth set up the conditions for compassion. As we search and find by happenstance or intention the terrible consequences of war, perhaps we are confronted with a need to think and imagine at a new level where the ‘virtual’ is known as embodied reality.

References

Bassett, Caroline (2006). ‘Remote Sensing’ in Sensorium. Embodied Experience, Technology and contemporary art, Cambridge, Massachusetts: London, England: the MIT Press.

Benjamin, Walter in Paul Virilio (2005, 2007). Tabula Rasa, City of Panic, Oxford, New York: Berg.

Farman, Jason (2010). Mapping the digital empire: Google Earth and the process of postmodern cartography, New Media Society OnlineFirst.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1986). Text and Interpretation in Hermeneutics and Modern Philosophy, Ed. Brice R. Wachterhauser, Trans. Dennis J. Schmidt, Albany: State University of New York Press.

Gibson, William (1984). Neuromancer, New York: Ace Books, 1994.

Google Corporate Information http://www.google.com/corporate/history.html [Accessed 19/9/2010].

Google Earth Homepage http://www.google.com/earth/index.html [Accessed 14/9/2010].

Google Press Center ‘U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and Google Join in Online Darfur Mapping Initiative’ http://www.google.com/intl/en/press/pressrel/darfur_mapping.html Accessed 14/9/2010.

Gregory, S. (2010), Personal Communication (11/8/2010)

Haraway, Donna J. (1991). Simians, Cyborgs and Women. The Reinvention of Nature, London: Free Association Books.

Jameson, Fredric (1972). The Prison-House of Language. A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian Formalism, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Kilday, Bill (2005) Seeing What Katrina has Wrought http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2005/09/seeing-what-katrina-has-wrought.html Accessed 14/9/2010.

Kozel, Susan (2007). Closer, Performance, Technology, Phenomenology, Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: The MIT Press.

Marmor, Kathy (2008). Bird Watching: An Introduction to Amateur Satellite Spotting, Leonardo, Vol.41, No.4.

Munster, Anna (2006). Materialializing New Media. Embodiment in Information Aesthetics, Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, Hanover and London.

Nussbaum, Martha (1996). Compassion: The Basic Social Emotion in The Communitarian Challenge to Liberalism, Eds. Ellen Frankel Paul, Fred D. Miller, Jr., and Jeffrey Paul, Cambridge, England, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Parks, Lisa (2005). Cultures (satellites and the televisual) In Orbit, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Parks, Lisa (2009). Digging into Google Earth: An Analysis of “Crisis in Darfur”, Geoforum, Vol. 40.

Lisa Parks (2010). Orbital Performers and Satellite Translators: Media Art in the Ag of Ionospheric Exchange, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 24:3, 207-216.

Rancière, Jacques (2004). The Distribution of the Sensible: Politics and Aesthetics, The Politics of Aesthetics, Trans. Gabriel Rockhill, London, New York: Continuum.

Stahl, Roger (2010). Becoming Bombs: 3D Animated Satellite Imagery and the Weaponization of the Civic Eye, Media Tropes eJournal, Vol.II, No.2, 65-93.

Turkle, Sherry (2006). ‘Tethering’ in Sensorium. Embodied Experience, Technology and contemporary art, Cambridge, Massachusetts: London, England: the MIT Press.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum ‘Overview Sudan’ http://www.ushmm.org/genocide/take_action/atrisk/region/sudan Accessed 18/9/2010.

Virilio, Paul (2005, 2007). ‘Tabula Rasa’, City of Panic, Oxford, New York: Berg.

Notes

1 These thoughts here are not the result of formalised research based on interviews and surveys. I am basing my idea on many conversations with my Media Cultures students over the last five years, and I have listened to how these conversations have changed during this time. Students see no problem in equating the virtual with the real, but a longitudinal study along these lines would be a highly productive enterprise.

2 See Roger Stahl (2009). ‘Becoming Bombs: 3D Animated Satellite Imagery and the Weaponization of the Civic Eye’, Media Tropes, Vol.2, No.2, 73 and Jason Farman (2010). ‘Mapping the digital empire: Google Earth and the process of postmodern cartography’, New Media Society Online First, 8-11.

3 When viewing Google Earth, you need to click the box that allows these layers to become visible.

4 Currently popular world-building games include Everquest, The Sims and Spore.

5 The context of this quote lies within Jameson’s discussion of Brecht’s ‘A-effect’. See Fredric Jameson (1972). The Prison-House of Language. A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian Formalism, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 5-51.

6 For an example of such a video clip, follow this link provided by an icon on the ‘Crisis in Darfur’ site to the Speaker Series on the HSHMM site: http://www.ushmm.org/genocide/analysis/details.php?content=2005-06-03 Accessed 19/9/2010

About the Author

Dr. Catherine Summerhayes is a Lecturer in Film and New Media Studies at the School of Cultural Inquiry, Research School of the Humanities and Arts, Australian National University. Her major research areas are in documentary, new media and performance studies. Her work has been published in several national and international journals and anthologies. Her monograph on Moffatt's films, The Moving Images of Tracey Moffatt, was published by Charta Edizione, Milan/New York in 2007.

Contact Details

Catherine Summerhayes Catherine.Summerhayes@anu.edu.au