Writing in and on the Margins

Writing in and on the Margins

Abstract

How does one communicate creative research across a diverse intellectual landscape? Does such work lodge itself uncomfortably in the margins – part scholarship, part creative practice? This paper describes creative research on marginal areas in the city called Disturbing Landscapes. It seeks to integrate scholarly interpretations of the significance of marginal landscapes with personal engagements with such places through creative writing.

*All images are the author’s photographs

Introduction

In a conversation about ideas, how does one communicate creative research across a diverse academic landscape? Does the work lodge itself uncomfortably in the margins: part scholarship, part creative practice? This paper describes my research on marginal areas in the city called Disturbing Landscapes. These are physical urban landscapes about which the paper seeks to integrate scholarly interpretations of the significance of marginal landscapes with personal engagements with such places through creative writing (where the interplay between creative expression and scholarly research does not flow easily).

Writing as creative research

Over the last decade, tactics and strategies by academics in design disciplines have been increasingly successful in gaining acceptance for theorised creative works within the conventional canons of research. Despite this, some of us who seek a seamless flow between subjective creative expression and scholarly observation still find our work occupies a ‘terrain vague’: an unstable space of oscillation and indeterminacy. But these spaces are also latent spaces: the spaces of the possible.

In this paper, some marginal places are explored to show the ways in which their marginality is an important aspect of everyday life. The author, referred to as the writer, and others, use creative writing as well as academic hermeneutics to interpret the meanings embedded in these places, thus reflecting both in and on the margins.

Hermeneutics of place

Developed as a means of practical translation of difficult religious texts and later of complex ethical and legal issues in cultural research, hermeneutics is often used to interpret the meanings embedded in the everyday world. Because meanings associated with ‘place’ are often layered and complex, research requires well-developed interpretative skills, including disciplined reflection and the hermeneutic cyclical process between meanings and ‘text’.

In this paper, the ‘texts’ are abandoned places whose qualities are evoked through creative prose and poetry as well as interpreted via academic writing. To do this, the writer has immersed herself in her emotional engagement with these places; however subjective writing is a far cry from disciplined reflection. To augment the subjectivity, the works of eminent writers have been mined for meanings related to desolate places.

Marginal lands are being replaced in contemporary cities by designs that, as ‘texts’, evoke neo-liberal capitalist symbols. The North American landscape theorist James Corner has written extensively about the hermeneutics of design. For Corner, interpretation requires recognition of the role of symbols that “relate the finite and mutable to the immutable and eternal, lived reality to ideas. Symbolisation is thus a fundamental operation in constituting meaning for human existence. As an operation, it belongs primarily to the realm of metaphor and poetics, not to objective reasoning.”(Corner, 1990:77)On this basis, one could argue that new designs replacing marginal lands use a limited palette.

The significance of metaphors, tropes and creativity

In creative writing about marginal places, metaphor is used in a social sense to understand one thing in terms of another. The pervasiveness of metaphors in everyday discourse suggests that they are critical mechanisms by which meaning is imbued, however, the creative power of metaphor lies in its ambiguity. This ambiguity is a key to understanding the uncanny qualities of marginal lands.

Apart from metaphors, Hayden White, in his Tropics of Discourse, argues that the study of tropes also helps researchers see the way people make sense of the world where:

understanding is a process of rendering the unfamiliar … familiar, of removing it from the domain of things felt to be ‘exotic’ and unclassified into another domain of experience encoded [through tropes]to be … non-threatening, or simply known by association.” (White, 1978:5).

Often designers go through the reverse process, seeking to make the familiar unfamiliar, hoping in the process to reveal other dimensions in phenomena. The importance of tropes is their ability to shuttle back and forth from representations in one medium to those in another, such as between the verbal and the visual, temporal and spatial, narrative and landscape (Potteiger and Purinton, 1998:34). This paper suggests that writing in and on marginal places requires such shuttling back and forth. At times the writer is writing within these places; at other times the researcher is outside observing them with the help of other writers.

Equally, creativity can play a role in hermeneutics. The art of interpretation needs to allow for creative, exploratory, and even playful ideas in order to be insightful. Here leaps in imagination are required to comprehend the world of others. Building on the Structuralists’ belief that culture is the act of encoding, cultural theorists suggest that these signs or codes are not innocent in the meanings they generate (Barthes, 1986:87-98).

The incompleteness of interpretation

The practice of interpretation will always be incomplete, fluctuating between luminous and opaque or, simultaneously, in light and shadow, as well as giving and withdrawing, where “the disclosure of one aspect necessarily conceals another” (Corner, 1991:125).In this process all previous understandings are recognised as having value, even if such interpretations have been discarded. Accordingly, interpretation of place is relative and responsive to particular situations and therefore unstable. Because an interpretation is situated and circumstantial, it never pretends to be more than one of many interpretations. As Gadamer observed, interpretations are “never completely definitive. Interpretation is always on the way” (Gadamer cited in Corner 1991: 126). Thus, there is not a final meaning. “Instead of closure and depth, there is an infinite play of meaning across surfaces.” (Potteiger and Purinton, 1998:33).

In this climate of either ‘a deep system’ or ‘infinite relativism’, the study of interpretations has become an important process in creative research. It is, however, the shift between the outsider as interpreter and the insider as creative writer that is explored here.

Narrating place

Matthew Potteiger and Jamie Purinton in their book, Narrating Landscapes, suggest that landscapes and places can be considered as narratives (1998). Keen to go beyond literal representations in the landscape, Potteiger and Purinton consider that there are equally narratives implicit in materials and in processes (1998: x). One can thus draw from literary theory the “metaphor of landscape as text”, the idea of inter-textual connections, multiple authorships and the role of the reader in constructing meanings (Potteiger and Purinton 1998: x). The context of the narrative acts as a boundary while also orienting the ‘reader’ to the kinds of story world they are entering; to give a designed landscape example, contrast entering the allegory within the 18th century garden to being hurled into the chaotic layering of a contemporary textual landscape, the Garden of Australian Dreams in the Museum of Australia, Canberra.

|

|

|

Thus narratives about place can be discursive realms in which contested values, ideologies, and beliefs can be negotiated, the process of discourse and the forms of negotiation acting as discipline and rigor in the nature of interpretation. However, this negotiation is the purview of the outsider and interferes with the introspection of the creative writer.

Writing about marginal places

Creative writing about marginal places can evoke the values of these places and by revealing such values suggest alternatives to current forms of urban development that do not erase all traces of the pre-existing. With the rapid changes to post-industrial landscapes, particularly around ports such as Sydney Harbour, the nature of redevelopment is of concern. Instead of exploring how a working harbour can be sustained and reconfigured to be relevant to a sustainable city in the 21st century, it would appear that cities such as Sydney are becoming consumerist playgrounds, characteristic of tourism-driven economics.

|

|

|

Spectacle and tourism-driven economics, as well as new urban living in emerging high-rise precincts, are seen as the panacea for post-industrial cities. Since the early 1980s planners and designers have been dominated by such neo-liberal utopianism in a desire to escape the dystopia of post-industrial ruins. Some contemporary theorists question this naïve utopian planning because it ignores the contributions within dystopias; in particular, learning to live with disorder and diversity (Kraftl 2007:120-138).

|

Creative writing can reveal the seductive melancholy in marginal places. The age and unkemptness in these open spaces and inner city voids – these shadows in the centre – quietly challenge the apparent complacency of the new. These places disturb at many levels but they can also be landscapes of optimism and hope, as explained by the urbanist, De Sola-Morales, in his manifesto Flexible Differences,“… the task to be accomplished is not the conservation of the past but the redemption of hopes that we held in the past – the redemption of optimism.” (De Sola-Morales, 1998).

Sites of optimism

Where are these sites of optimism that are exploring a different relationship between landscape and people? They are certainly evident in the marginal landscapes of shrinking cities such as the innovative way abandoned lands are being used in Berlin and Detroit. But they are also in resilient cities that allow for complexity.

|

|

One can ask why redevelopment in Rotterdam – one of the busiest ports in Europe – is able to maintain layers of the future, present and past, while Australian port cities surrender their layered landscapes to become shallow surfaces for spectacle and consumption. What is it that tempers Rotterdam’s urban development so that complex landscapes can co-exist, including left over spaces, wastelands and urban voids, those messy, unkempt, apparently unused and disturbing places which are so important to the patina of cities? These comments are not driven by nostalgia alone; rather they question simplistic planning which encourages redevelopment of all vacant sites, irrespective of their former or current use.

A researcher’s questions

Such a way of seeing the urban landscape prompts some relevant research questions:

- Why are marginal lands concealed or redeveloped?

- What is it about marginal lands that people find disturbing?

- Are not landscapes that disturb just as important as landscapes that delight?

These questions are unlikely to be answered by surveys or even in-depth interviews; however clues lie in certain eminent texts about our existential relationship with places, such as those by Walter Benjamin, Jung, and Freud. One can also add to the discourse voices such as Camus, de Sola-Morales, Vidler, with some brief thoughts from Lacan and Kristeva – all wedded to the value of marginal spaces in the city.

Creative writing can also reveal Heidegger’s deep dwelling (Heidegger 1962) as well as a particular creativity in the last vestiges of marginal urban space; small left-over spaces, urban voids, easements and sidings as well as derelict industrial lands. To support this, the work of current urban artists who walk the city – ‘Stalker’ from Italy, Boris Sieverts from Germany, Misguide from Britain, and ‘Stalking Sydney’(Nov 2006) – bring out the experience of these places through performance and other creative expressions.

Intuitive explorations

The writer was particularly drawn to the notion of ‘unheimlich’ or the ‘uncanny’, suggesting that her profound connection with these marginal waterside areas were related to her childhood. The places where she once wandered and explored alone are disappearing, to be replaced by fortified luxury high-rise residential areas. She reflected:

|

|

|

It is the subtle and familiar qualities that are disappearing; things that are often only noticed by a child. The inner suburbs of Sydney have, until recently, been rich in small left over spaces. Many of the streets in Sydney’s foreshore suburbs ran down steep slopes only to be truncated by the Harbour, where they often turn into makeshift parks, merely as wide as the street.

It is as though a surveyor, sitting at his flat drawing board in an office far removed from the Harbour’s rocky knolls, drew an orderly grid of streets. When folded over the topography, the grid creaked and crumpled, particularly around its lower edges resulting in left over spaces which dot the foreshore edges, some as worn grass, others as rocks with scrambling nasturtium held back by salt spray.

Our neat surveyor in his white shirt and subdued tie, with his equally neat map, inadvertently created the untidy places that give children so much joy.

I was one of those children. I was drawn to these uncanny spaces where tough waterside plants or clusters of tiny barnacles at the water edge allowed me to enter another world. Once through the imaginary threshold, I would roam my secret landscape until fading light would force me to retrace my steps and once again be in the adult world.

Neither proper parks nor legitimate streets, these inconsequential left over spaces had a strange and uncertain quality. The street would continue for a short distance – bitumen, often two rows of Brush Box trees, sometimes even two footpaths with gutters; but uncertain of where it was going, the bitumen would peter out into rough gravel and the rows of trees would falter and then stop. Later a Council Engineer would lay a timber log across to try to make a definite end to the street but it was too late; the street had already blended with the Harbour rocks, forming a clandestine and resilient relationship. These small, ignored, unkempt places had a quiet defiance and it was here that I buried my treasure (Armstrong, 2010: 7-8)

Conflicting urban explorations

In the mid 1980s, Margaret Thatcher’s policies for the massive redevelopment of London’s Docklands were free of social, cultural and environmental restraints. In other cities, spectacles such as Festival Markets became the catalyst for redevelopment. These were the unrestrained templates for urban change; however during the 1990s, the critique of the ‘spectacle city’ began to grow. Also in the 1990s, urban theorists from Barcelona were exploring the value of Terrains Vagues in cities. This prompted the writer to explore the mysteriousness and poetic beauty of leftover or derelict spaces and wastelands.

|

It appeared that there was a compelling need by politicians, city planners and the community to remove marginal and derelict places that were deeper than merely city promotion or ‘boosterism’. Derelict sites carry messages of failure, particularly abandoned industrial sites. As uncomfortable reminders, there are strong reasons for them to be replaced by buoyant new developments. The writer called this the ‘culture of forgetting’ and suggested that this is sustained by a form of ‘urban delirium’ of spectacular events. As a result, her work is structured around three themes: REMEMBERING, FORGETTING, AND ACCEPTING.

Remembering – some reflections

Most people recall the landscapes of their childhood. Often such places were ordinary landscapes that had been lost without one noticing. It is only through remembering that a strange, difficult to define, emptiness is felt. Such memories reflect a time when landscapes helped children to understand themselves, marveling at their intrepidness as they explored the marginal places threaded through their neighbourhoods.

In those middle years of childhood children grew to understand who they were within the wider world. A child’s natural eagerness for adventure was satisfied by places beyond the watchful gaze of parents. Making forts and cubbies, they played with friends, often ranging over unkempt lands. Here, they experienced themselves as heroic adventurers collecting the strange things that could be found in discarded places. They imagined themselves as fearless; their reputation hinging on displays of bravado, physical strength and dexterity. Clive James recalls a typical Australian childhood.

When we were kids we hunted the cicada.

The pet cockatoo bit like a barracuda.

We were secret agents and fluent in pig Latin.

Gutsing on mulberries made our lips shine like black satin (James, 2007)

For some children and adolescents, marginal places are just as meaningful as formal parklands. DBC Pierre evokes such landscapes in his novel, Vernon God Little, where a young adolescent on a bicycle comments on the wasteland on the edge of an American town.

Bushes on Keeter’s trail are bizarre, all spiky and gnarled, with just enough clearing between them so the unknown is never more than fifteen yards away …

Old man Keeter owns this empty slab of land, miles of it probably, outside town. He puts a wrecking shop by the ole Johnson road, Keeter’s Spares and Repairs – just a mess of junk in the dirt, really. … mostly just bleached beer cans and shit. … Martirio boys get their first taste of guns, girls and beer out here.

You never forget the blade of wind that cuts across Keeter’s(Pierre, 2003: 97)

The child of today has grandparents who remember childhood as rich in sensory excitement, activity, diversity and challenge. One wonders what childhood memories will be in landscapes that are losing diversity and intimacy to be replaced with increasingly

programmed and uniform places.

|

|

One could ask why the city of spectacle is the major paradigm for urban development today. Today’s cities are peppered with spectacular architectural interventions, however, more pervasively, it is the new urban landscape that provides the setting for spectacle and play. Such landscapes slide over the still warm body of the industrial city where urban playgrounds are vital to the culture of forgetting. These brightly coloured places have bleached the city, erasing dark and derelict spaces, making it easy to forget. The writer asked:

Forgotten Waterfronts

Hovering giants glow in the afternoon light,

Curling pipes revealing their rusting might.

Whither those powerful and disturbing ghosts?

Distant sounds of crane, ship and horn,

Mournful sirens call workmen at dawn.

Whither those powerful and disturbing ghosts?

Haunting spaces, familiar and unfamiliar

Beauty revealed in derelict jagged shapes,

Dry grasses push through dusty scapes,

Whither those powerful and disturbing ghosts?

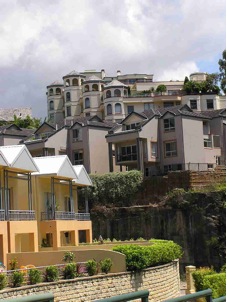

Now pastel boxes, closely pressed cheek by jowl,

Crawl over industrial sites, sleek by foul.

Whither those powerful and disturbing ghosts?

Coloured sticks in the sky, guilt allay,

Monorail glides over cafés built for play,

Whither those powerful and disturbing ghosts?

Lonely container ships slip through water play,

Refusing defeat, battle lost for today,

Whither those powerful and disturbing ghosts?

Memories call to you, my love, as melancholy places ebb away,

Waterfront wastelands speak to us. Their messages say,

Whither those powerful and disturbing ghosts?(Armstrong, 2010: 13)

Bleaching Benjamin’s Flâneur

People in today’s spectacle city appear to be as happy and unconcerned as the Parisians who came under the writer Walter Benjamin’s(1999) gaze at the turn of the 20th century. As a counter to the unquestioning acceptance of the new, Benjamin was also drawn to obsolete places in the city. Through the eyes of his wandering flâneur, he saw the city as a montage of present glitter overlaying past ways of life. It was the very juxtaposition of old and new that enabled people to celebrate the optimism in the city’s progressive image.

But in today’s city so much of the past has been erased that the image of the modern city has no foil. Without its historic context, the city is strangely ungrounded. The concept of Benjamin’s flâneur as a discriminating urban promeneur, to some degree ambivalent about the new public spaces, is now difficult to find. Instead the flâneur has been bleached into a ‘spectator’ within a consumer-oriented city of ephemeral events and vast areas for shopping.

Can today’s ‘spectators’ observe the present city with discernment now that most of the traces of the recent past have gone? What do they compare the present with? City promotion or ‘boosterism’ seems to ensure that the predominant criteria are bigger and better spectacles. Is this a form of urban hysteria and delirium in order to avoid looking back? What are people avoiding by not allowing the quiet spaces of just yesterday to sit beside the exuberant present?

Urban digital spectacle

Along with buoyant urban renewal, spectacle cities now compete for tourists seeking the new commodified play including huge sporting events such as the Olympic Games which is the ultimate media spectacle, showcasing particular cities as fantasy images. Sport is big spectacle business. Cities are alive with huge media screens, giant figures of muddy footballers or sweaty athletes flickering on the facades of buildings. Dramatic new cultural centres designed by signature architects, and bigger, more vivid, shopping malls, also render the city into hyper-active pleasure zones.

It is as though the modern city is to be saved by festivals and pageants. There are, however, some whispers of dissent. Re-invoking the memory of the Situationists, some activist architects and artists, such as the Italian collective ‘Stalker’ (online), are suggesting that city dwellers could recover some autonomy through random encounters and transgressions outside prescribed and designed urban space. The ability to pause and reflect on current urban life lies in the empty ‘waste’ lands. The few that are left, in their very emptiness, call for contemplation about the urban hysteria/delirium of today.

Fear of remembering – further reflections

One has to work hard at forgetting because memories can assert themselves in unexpected ways. The culture of forgetting can be jolted by uncanny places where a minor detail can appear both strange and yet disturbingly familiar. There is something vague that one remembers but it is an uncomfortable memory.

For many people, the more pervasive the erasure of left over spaces the stronger the sense of unease about those few that remain. It would seem that there is a need for all traces of wastelands and derelict sites to be removed, so that people can collude with a story of an unbroken, untroubled recent history.

The desire to forget means left over spaces can now assume a sinister presence. They can convey a sense of dread, a sense of lurking unease. Despite this, such urban estrangement has possibilities because it could equally be a way of connecting and deep grounding. Rather than repressing it, the unease is a way of accepting otherness, the indeterminate, even a kind of lyricism about the savageness of the dark.

But this is the unruly city that urban planning seeks to discipline. Whatever does not conform to an ordered and progressive perception of urban space is seen as an urban blight to be eradicated as soon as possible. Accordingly, master plans are used to purge urban space of its complexity and the spontaneous activities that shape the everyday experience of the city, and in doing so, planning is an active accomplice in this general urban amnesia.

Through this process, the city with patina – a mosaic of light and dark places, complex and layered and rich with possibilities – is being lost. The city with patina is not afraid to remember. It is not afraid of disturbing uncanny places.

|

|

The state of forgetting and remembering in the city embodies certain contradictions. Paradoxically, a particular kind of forgetting where one unselfconsciously loses oneself can provide the condition for memories to reappear. Marginal spaces can induce this state – a kind of trance. In these left over spaces we can experience a quiet reverie which may include disturbing memories of being afraid and alone, or tender memories of a time when one roamed as a child, full of the wonders at a shiny shard of glass or the distant views of the city edge. However, it would seem marginal lands are to be hidden from view. The writer muses:

The first time I became aware of the beauty in industrial landscapes, I was required to conceal them. In the early 1980s, as a landscape designer, I was expected to ameliorate the impact of vast industrial sites; coal handling works, oil pipelines, expressways and dams. But it was only the visual impact that seemed to matter. As long as the ugliness was hidden, other effects could be ignored.

To me, coal-handling works were beautiful. Rows of immense black mounds bordered by a frame of elevated tracks to hold startling orange cranes and gantries echoed Mondrian’s colourful geometry. If this was a blot on the grey-green, landscape, it was a vibrant one.

And it was alive. Great tubular arms, moving fluidly along the rails, misted the dusty coal mountains, transforming the scene into a multi-breasted Madonna of glistening black cones. Here in the hinterland, lay a huge pop art installation which the wider community saw as visual blight. So I designed a fortress of equally huge mounds intended to be covered with olive green shrubs. These however were not misted. The vast embankments dried and cracked; a few straggling plants clinging tenaciously like Fred Williams smudges. It was ironic that this drabness was intended to conceal the drama of a coal handling works.

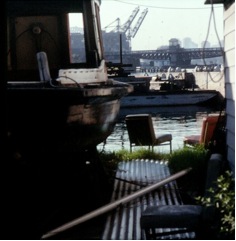

Until recently, the same tension between industrial ugliness and bush beauty was evident around Sydney Harbour where similar coal handling works were less easily hidden. Unlike their shiny colourful progeny, the elderly works had a muted beauty. Long rails resting on a viaduct of arches and medieval-like buttresses evoked a history much older than their mere one hundred years.

While this industry lived, grey cranes moved slowly beside rusty ships, lying heavily in the water. Under evening floodlights, their angled arms were transformed into a giant spider’s web silhouetted against bulky walls while the sounds of men at work penetrated the night.

Such beauty within the ugliness; sadly, now erased by city image-makers.

Today, a different visual blight occupies the inlets and bays, invading like weeds. New fortresses, concealing their sinister indifference in pastel colours, have replaced the memory of grey dustiness. The rewards for a few in the new economy do not need to be concealed, merely guarded.

The first time I worked with industrial landscapes, I was colluding with a deceit that allowed the beauty of a complex landscape to change into the shallow complacency of consumerism; dark working landscapes overcome by pastel playgrounds. Such is the beauty in the eye of the beholder.’ (Armstrong, 2010: 29-30)

Forgetting and remembering do not flow seamlessly – many things are filtered out. Such selective amnesia usually relates to memories that shame, and therefore avoided by replacing them with more pleasant thoughts. This requires constant attention. Freud understood this. He saw how the uncanny does not remain forgotten but intrudes into memory at unexpected and often humiliating times.

Uncanny shadowlands

The writer suggests that disturbing landscapes in the city are uncanny shadowlands where shadows are the Jungian archetype of our ‘other’. They are places on the margins such as the area around drainage culverts, old quarry faces, and spaces cut off or under motorways. An eerie presence also hovers around empty parking areas, rundown shopping malls and abandoned petrol stations.

|

|

In their untidiness and dereliction, they disrupt the current need for a smooth, coherent city. This transgression alerts people to the idea that the line between the buoyant and the decaying may be arbitrary and that they, in fact, may exist in both states. These places are abject where the unclean is both part of oneself and not part of oneself, like unwanted bodily fluids. Reminders of this can arouse a sense of uncanny disquiet. The very sites of former industry are pregnant with possibilities yet evidence of the soiled city body is scraped away. Like Kristeva’s (Kristeva and Roudiez, 1982) abject menstruating woman, these sites are seen as contaminated instead of fertile with opportunities for creative and innovative ways to transform cities.

The uncanny reveals the irreconcilable attempts to create an ordered predictable modern world, free from contradictions and uncertainties. This need for certainty is different from previous eras where people were capable of living with uncertainties and where the unknown was a kind of darkness that, although beyond control, was redeemed through spiritual worship.

Dark spaces and resilient dwelling

Left over urban spaces are often dark places. These indeterminate black areas just beyond brightly lit spaces evoke the labyrinth and the gothic horror of the 18th century sublime where one could fall into a void of infinite depth.

At the darkest recesses and forgotten margins, dark spaces are assumed to hide all the phobias that can return to haunt. Wastelands tap into one’s imagination and unconscious to produce a sensory effect of dissonance. One is unwillingly to be drawn into the situation of indeterminacy, instability and fragility. But avoiding this is a Faustian bargain. By protecting oneself from experiencing uncertainty, one’s ability to be resilient and flexible is undermined.

Learning to live with this dissonance, rather than hastily removing those unsettling places can allow people to dwell with potent insights. It is the ability to move between the grey marginal spaces and the colourful new, between play and reflection that brings about resilience. Discomfort can be seen as a positive urban experience because dense, disorderly cities contain the tools to teach people how to live with flexibility and cope with risks.

Accepting

Exploring the fear of uncomfortable memories suggests there is value in accepting the positive aspects of marginal lands, including the beauty of dereliction. They allow people to commune with ‘place’ in a different way, for within such sites one can regain the ability to accept the ‘ugly’ and learn from their strange and resonating qualities.

Sensual aesthetics in abandoned sites

What is the beauty in abandoned sites? Certainly it includes colour, form, texture and a particular materiality, but there is much more. There is the interplay of light and dark, iridescence and reflection, as well as evocative sounds and smells. Both sublime and picturesque, both powerful and vulnerable, the aesthetics within abandoned sites form a complex embroidery of decay. (Trigg 2004)

Standing in contrast to aesthetically designed and socially regulated spaces neglected sites can provide an aesthetic of disorder, surprise and sensuality, offering ghostly glimpses into the past and tactile encounters with a forgotten materiality. These are sensuous landscapes where seductive melancholy is heightened by the eroticism of danger. The writer reflects:

… they can jolt us with strange aromas, often emanating from dumped rubbish along tracks that seem to lead nowhere. An old faded fabric, twisted and soiled, strewn near a log, hints at something sinister; arousing a shiver of unease. A broken washing machine, rust etching into its white surface, leans abused and abject; metal cans, discarded car parts – strange disconnected objects – reveal an abstract beauty…” (Armstrong, 2010: p 30)

Walking the margins: re-visiting Dérive

Some architects and artists have started to study urban wastelands through the act of walking, for example, the work of Boris Sieverts (2004) the German architect/artist, in Cologne. His studio is essentially a city travel agency from which Sieverts organises walks in city outskirts, focusing on areas of wasteland and empty lots. He analyses the sensations brought about by such walks and tries to formulate their complexity as “poetic densification”, thus transforming the usual way wastelands are perceived. He suggests that urban wastelands are one of the last urban adventures.

Intriguing strategies are also proposed by ‘Stalker’ – an Italian collective of activist architects/artists – who undertake numerous projects in abandoned urban spaces, employing the act of dérive. Their various ‘walks’ through urban voids have criss-crossed Rennes, Milan, Miami and Berlin. Similar to the Situationists, their walks result in abstract maps which are reverse readings of the city where the urban mass turns into an amorphous background in contrast to the vitality of the city’s marginal zones.

They adhere to their Manifestostating that:

Stalker is together custodian, guide and artist for these sites. In the multiple roles, we are disposed to confront at once the apparently unsolvable contradictions of salvaging through abandonment, of representation through sensorial perception, of intervening within the unstable and mutable conditions of these areas. (Author’s emphasis) (Stalker, online)

They seek to achieve continuity and penetration into abandoned areas in the belief that such actions will:

… enrich and give life to the city through the continuous and diffused confrontation with the unknown. In this way it will be possible to recover within the profound heart of the city, the wild, the non-planned, the nomadic … (Stalker, online)

Micro-tactics in derelict landscapes

Because of the huge scale of increasingly derelict landscapes in post-soviet Europe and large post-industrial cities like Detroit, another movement has developed micro-tactics for shrinking cities. Under the EU-funded Shrinking Cities Project, these urbanists see the vast derelict landscapes as open laboratories for experiments attracting self-reliant pioneers, including urban farming, guerrilla gardening, ad hoc co-operatives, and vigorous art and music installations. The Shrinking Cities movement focuses on a new form of urban ecology, both people and systems, suggesting that “in the fault lines of the Modernist city, fresh and rebellious ideas and designs are emerging as an “architecture of resistance.” (Shrinking Cities Project, 2002-6: online).

Project Shrinking Cities, directed by Philipp Oswalt and Klaus Overmeyer, actively encourages new ideas for temporary land uses for urban wasteland. In parallel, the group, Multiplicity, led by Stephano Boeri, act like urban detectives. They are searching out innovative activities in wasteland sites where, Boeri points out:

It is in these sites, at the periphery of geopolitical imagery that Europe is changing most rapidly. It is here that innovations emerge and it is possible to imagine the future … (Boeri, 2005: 153-4)

Paradoxes abound in contemporary cities. It is possible that the shiny new high-tech cities are not suited for the future and may well become the wastelands of tomorrow. Meanwhile drab derelict shrinking cities, in their abject state, have become sites for experiments and innovation exploring new ecologies, new ways for diverse people to live together, and new ways for urban dwellers to subsist. This paper suggests they are empowering landscapes, where transitory uses can be used to explore innovative and unusual ways to live in the 21st century.

Some final thoughts

Thus within today’s cities there is a complex mosaic of disturbing landscapes. They include the tiniest weed-infested left over spaces, the vestiges of market gardens struggling at the city edge, the vast derelict industrial sites, and the streamlined motorways that carve through the landscape in disturbingly surreal ways. As a researcher and a creative writer, the original questions have not been fully answered but academic and creative writing has shed some light on:

- Why there is a need to conceal or develop marginal lands

- What it is in marginal lands that is disturbing, and that landscapes that disturb are just as important as landscapes that delight.

In writing in and on the margins, the author is not alone. Others have explored the hermeneutics of the failed industrial project and why people need to conceal this. Others have also written eloquently about the qualities of marginal landscapes and how these qualities are important for resilient urban dwellers. Finally, the author as creative writer has written about the layers of meaning embedded in these places, narrating her places through poetry and prose embellished with metaphors and tropes to bring out the sensual beauty and poignancy of these places. Also through creative writing, the paper hopes to reveal the vital importance of marginal lands for children in current over-protected and over-designed cities.

References

Armstrong, H. (2000). ‘Design as Research: Creative Works and the Design Studio as Scholarly Practice’ in Architectural Theory Review. Vol 5(2) November 2000.1-14.

Armstrong, H. (2003). ‘Interpreting Landscapes/Places/Architecture: The Place for Hermeneutics in Design Theory and Practice’ in Architectural Theory Review, vol 8 (1) pp 63-79.

Armstrong, H. (2010). Disturbing Landscapes [unpublished manuscript]

Barthes, R. (1986). ‘Semiology and the urban’ in M. Gottdeiner & Ph. Lagopoulos (eds), The City and the Sign: An Introduction to Urban Semiotics, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 87-98.

Mostafavi & Najle. (eds). (2003). Landscape Urbanism, London: Architectural Association Press.

Benjamin, W. (1999). The Arcades Project, [translated by Howard Eiland & Kevin McLaughlin] Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Boeri, S. (2005). ‘USE-Uncertain States of Europe in Park, K’ in Urban Ecology: Detroit and Beyond, Hong Kong: Map Book Publishers, 153-4.

Camus, A. (1970). ‘A Short Guide to Towns without a Past’ in Philip Thody (ed), Lyrical and Critical Essays [translated by Ellen Conroy Kennedy] New York: Vintage Books

Corner, J. (1990). ‘A Discourse on Theory I: Sounding the ‘Depths’ – Origins, Theory, and Representation’ in Landscape Journal, 9, 1 (Spring 1990): 61-78.

Corner, J. (1991). ‘A Discourse on Theory II: Three Tyrannies of Contemporary Theory and the Alternative of Hermeneutics’ in Landscape Journal, 10, 2 (Fall, 1991): 115- 133.

Crinson, M. (ed) (2005). Urban Memory: History and Amnesia in the Modern City London: Routledge

De Certeau, M. (1988). The Practice of Everyday Life [translated by Steven Rendell] London: University of California Press.

De Sola-Morales, I. (1996). ‘Terrain Vagues’ in Quaderns 212 Tierra-Agua. Barcelona: Collegio de Arquitectos de Catalunya, 34-44.

De Sola-Morales. (1998). Differences: Topographies of Contemporary Architecture. [translated by Graham Thompson& Sarah Whiting] Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Edensor, T. (2005). Industrial Ruin New York: Berg Publishers.

Freud, S. [trans 1985]. The Uncanny in Art and Literature (ed) Dickson, A. London: Penguin.

Foster, H. (1996). ‘The Artifice of Abjection’ in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the Turn of the Century, Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 153-168.

Gadamer, H. (1976). Philosophical Hermeneutics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and Time. New York: Harper & Row.

James, C. Times Literary Supplement, April 2007

Kraftl, P. (2007). ‘Utopia, Performativity and the Unhomely’ in Environment and Planning D : Society and Space 2007(V25), pp120-143.

Kristeva, J & Roudiez, L.S. (1982) Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (European Perspectives Series)

Lacan, J. (1977, 1982). Ecrits (1901-1981): a Selection, [translated by Alan Sheridan], London: Tavistock

Mis-guiding the City Walker, Cities for People: The Fifth International Conference on Walking in the 21st Century, Copenhagen (2004)

Pierre, DBC (2003), Vernon God Little, London: Faber and Faber.

Potteiger, M & Purinton, J. (1998). Narrating Landscapes, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Sadler, S. (1999). The Situationist City, Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Schön, D. (1973). The Reflective Practitioner, New York: Basic Books.

Shrinking Cities Project (2002-6). http://www.shrinkingcities.com

Sieverts, B. Archilab (2004). http://www.archilab.org/public/2004/en/ft2004.html

Stalking Sydney. (2006). Liquid Cities Symposium Sydney, Nov 2006

Trigg, D (2004). ‘The Uncanny Space of Decay’ in Psy-Geo Provflux Vol 1 (1) http://pipsworks.com/pipsworks.com/crosswalk/prov04.html

Vidler, A. (1992). The Architectural Uncanny, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

White, H. (1978). Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism, Baltimore Md: Johns HopkinsUniversity Press.

Wrights & Sites (2006) A Mis-guide to Anywhere, Institute of Contemporary Arts: London.

About the Author

Dr Helen Armstrong is Professor Emeritus of Landscape Architecture, QUT. She was the Founding Director, Cultural Landscape Research Unit. She has been an academic in landscape architecture since the late 1970s, both in Australia and overseas. She has undertaken a number of heritage research projects related to cultural landscapes, including Australian landscape history, Queensland cultural landscape as a contested terrain, migrant place-making and the contribution of cultural pluralism to Australian cultural heritage. She is also Adjunct-Professor at the Centre for Cultural Research, UWS where she has been researching marginal landscapes.

Contact Details

Helen Armstrong h.armstrong@qut.edu.au