The Women of Dolours: Sunday’s Well & Lifting the Shroud of Silence

The Women of Dolours: Sunday’s Well & Lifting the Shroud of Silence

Abstract

While carrying out field research in Ireland in the winter of 2010, I visited the former Magdalene Laundry in Sunday’s Well, Cork City. Situated on a hill overlooking the river Lee, the laundry was part of a vast network of schools, convents, asylums and hospitals that were funded by the Irish government and run by various religious orders. Locating the dilapidated laundry proved to be incredibly difficult due to the vague directions from locals and the labyrinth of narrow avenues and blind alleys leading up to the buildings. While exploring the laundry itself, it became apparent that it shared a perimeter wall with the local, historic prison which was a local tourist attraction. This has led me to question, how is it possible to make similar, adjoining sites of incarceration simultaneously visible and invisible? What techniques of governmentality are at play that privileges one and silences the other? Through word, photography, and theory this article focuses on the complex and no doubt contradictory experiences of lives as they were lived within Ireland’s Architecture of Containment.

***

I tried to do things that involved a personal commitment that was physical and real, and which would pose problems in concrete, precise, and definite terms in a given situation (Foucault, 1978: 24).

On August 23, 2003, journalist Olivia Kelly reported in the Irish Times that the remains of one hundred and thirty three Magdalen women – that is, women incarcerated in what were known as Magdalen laundries 1 for misdemeanours generally pertaining to sex – were to be exhumed from the High Park Convent in Dublin. The undertakers carrying out the task went on to discover a further 22 sets of remains which were unaccounted for. Of the 155 sets of remains discovered in the communal plot, the deaths of eighty so-called penitents had not been officially recorded. 2 All the remains, with the exception of one set which was reclaimed by family, were sent to Glasnevin cemetery for cremation – a practice which, interestingly, was until recently condemned by the Catholic Church. While it is a criminal offence in Ireland not to record a death that occurs on one’s property, no-one was charged or made accountable.

Furthermore, the Irish government expedited the exhumation licence for the unaccounted women. These women who failed to live up to the narrow moral codes of Irish society were to be denied the last and most basic right of Irish citizenship. In death, as it was in life, they slipped silently from view: we do not even know their names. How then, can one bear witness to the lives of these anonymous women? How might it be possible to give voice to their stories when even their physical remains have officially been made to disappear, and institutional records of their lives either no longer exist, or, if they do, are not accessible?

In James M. Smith’s (2008), Ireland’s Magdalen Laundries and the Nation’s Architecture of Containment, Smith, like Maria Luddy (1995) and Frances Finnegan (2001) before him, argues that our knowledge of the Magdalen “laundries will never be complete until the religious orders make their archival records available” (2007:138). Indeed, Smith has suggested that “this historical vacuum largely explains why Ireland’s Magdalen laundries exist in the public mind at the level of story rather than history” (2007: 138).

Whilst these claims are interesting insofar as they point to the paucity of information available on what was in fact a massive practice of institutionalisation that spanned approximately a century and a half, they are nevertheless informed by a number of connected assumptions that I regard as problematic. For example, Smith’s statement reiterates a commonly-held distinction between truth and fiction, implying that the former is superior to the latter, that ‘truth’ consists of a fact (or set of facts) waiting to be discovered, and that justice can only occur once ‘the truth’ (as singular and unambiguous) is revealed or emancipated from the power of the institution(s) that withholds or distorts it. In Truth and Power (1980b) Foucault argues that this commonly held conception of truth is less an empirical fact that is outside power, than an effect of the political economy of truth as it operates in western modernity. Truth, he writes:

… is a thing of this world: it is produced only by virtue of multiple forms of constraint. And it induces regular effects of power. Each society has its regime of truth, its “general politics” of truth: that is, the type of discourse which it accepts and makes function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true and false statements, the means by which each is sanctioned; the techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true (1980b: 131).

In other words, for Foucault, what counts as truth is always-already a discursive fiction, an effect of situated, sanctioned knowledges, practices, mechanisms, and so on, that constitute what they purport to merely describe. And yet ‘truth’ retains the power of an imperative. In Society Must be Defended (2004) Foucault claims that in a society such as ours, “we are condemned to admit the truth or discover it” (2004: 24), to confess, or to detect. And both confession and detection are framed in the dominant imaginary, in terms of liberation, not only of the truth, but more particularly, of the self. But for Foucault, the “infinite task of telling” (1980a: 20) the truth (either of the self, or of a situation one is investigating) does not liberate the self from power. Rather, specific, situated forms and practices of “truth-telling” shape the subject (of knowledge) in accordance with dominant values, ideas and ideals: positions the self and the ‘truths’ s/he tells as creditable or discredited, as able to be heard or silenced. Power, Foucault states, “institutionalizes the search for truth, professionalizes it, and rewards it” (2004: 25), and nowhere is this clearer than in the context of the university with its discipline-specific knowledges and practices, its codes of conduct, its formal modes of recognition and reward, of making heard and silencing. Given this, the role of the intellectual is not, at least as Foucault sees it, to reveal “the truth” in and through institutionally sanctioned pedagogical methods, but rather, to critically interrogate “the ensemble of rules according to which the true and the false [or the fictional] are separated and specific effects of power are attached to the true” (1980b: 132), to detach “the power of truth from the forms of hegemony, social, economic, and cultural, within which it operates at the present time” (1980b: 133).

Interrogating the production of ‘truth’, the role and function of what is taken to be true (in any given context), entails recognising that official records and/or knowledges (such as those Smith presumes will tell the truth of life in the Magdalene laundries) are perspectival – that is, they are written from the point of view of someone, of the institution that produces them, rather than being objective statements, views from nowhere. 3 In other words, such records – presuming that they do exist – constitute what Donna Haraway (1988) refers to as “situated knowledges”: they tell specific, located, legitimised stories, stories in which the voices of the women incarcerated in the laundries are unlikely to be heard.

Thus, even if the Church were to release the records from its many institutions of containment, such documents would not, I suggest, simply reveal the truth (despite their claim to objectivity) and thus fill what Smith refers to as the “historical vacuum” surrounding the Magdalene laundries: nor would they necessarily provide access to what Foucault has described as subjugated knowledges. Foucault uses this term to refer to:

a whole series of knowledges that have been disqualified as non-conceptual knowledges, as insufficiently elaborated knowledges … knowledges that are below the required level of erudition or scientificity…the knowledge of the psychiatrized, the patient, … the delinquent’ (Foucault, 2004: 7)

He argues that such knowledges contain “the memory of combats… that [have] … been confined to the margins” (2004: 8).

In making this claim however, Foucault is not suggesting that the kinds of confessional narratives associated with the truth-telling practices of ‘the marginalised’ (for example, autobiographies of survivors, testimonials given in the context of government inquiries, and so on) are somehow more authentic, are closer to the truth than, for example, the records kept by a particular institution, or the histories of incarceration penned by traditional historians. For Foucault, conflicting accounts of a particular event, institution, personal history, legislative change, Act of parliament, and so on, should be conceived not so much “as a battle ‘on behalf’ of the truth, but [as] a battle about the status of truth and the economic and political role it plays” (1980b: 132).

Critically interrogating this battle means necessarily eschewing the tendency to give precedence to one form or practice of ‘truth-telling’ over another, to constitute one account as true and the other as false, fictional, inferior, or illegitimate and, by association, to naively champion one group (as an homogenous entity) over another. This is particularly apparent in Foucault’s use of the term “subjugated knowledges” to refer not only to “knowledges that have been disqualified” (2004: 7), but also to “historical contents that have been buried or masked in functional coherences or formal systematizations” (ibid.), to the “heterogeneity of what was imagined consistent with itself” (1984: 82).

Historical events resonate not merely through the archives that have been collected, but also through its gaps – the historical material that has been lost or has not been collected … the histories that find no place within written historical records, but where they continue to ‘haunt’ this record through their silences, opening up gaps within the “historiographic enterprise” (Danaher, Schirato & Webb, 2000: 57-8).

Following Foucault then the task of a photographer recording the detritus of lives once lived within the walls of containment, is not to discover the truth, but in recording the traces of lives once lived in these places which stand on the cusp of disappearing forever, is instead an attempt to undertake what he calls “genealogical investigations” (ibid.), and whilst the practice of genealogy differs from that of History in significant ways, genealogy is both reliant on and committed to History 4. In Nietzsche, Genealogy, History Foucault states that “genealogy does not oppose itself to history … on the contrary, it rejects the meta-historical deployment of ideal significations, and indefinite teleologies” (1984: 77). In other words, genealogy as a critical practice eschews metaphysics, while History, as a positivist discipline with a set of sanctioned practices informed by shared (often unquestioned) assumptions, has functioned, at least in western modernity, as the handmaiden of ‘truth’ (as singular, discoverable, liberatory, and so on).

What the genealogist finds if s/he listens to history is not, according to Foucault, “a timeless and essential secret” (1984: 78), a unified, coherent and immobile truth, but rather, contingency. As such, genealogy uproots, disrupts, deconstructs dominant ontologies of knowledge, self, time and space (as singular, coherent, stable, and so on) Genealogies:

… are about the insurrection of knowledges … an insurrection against the centralizing power-effects that are bound up with the institutionalization and workings of any scientific 5 discourse organized in a society such as ours. … Genealogy has to fight the power-effects characteristic of any discourse that is regarded as scientific (2004: 9).

I take this to include academic discourses about (legitimate) knowledge, and religious (in this case Catholic) discourses about morality.

Foucault continues:

genealogy is, then, a sort of attempt to desubjugate historical knowledges, to … enable them to oppose and struggle against the coercion of a unitary, formal and scientific theoretical discourse. The project of these disorderly and tattered genealogies is to reactivate local knowledges … against the scientific hierarchicalization of knowledge and its intrinsic power-effects” (ibid: 10).

And the aim of this process of reactivation is not to promise a certain future, which, as Wendy Brown notes, progressive history does, but “to incite possible futures” (1998: 37). Such incitement, argues Brown, following Foucault, “dictate[s] neither the terms nor the direction of political possibility, both of which are matters of imagination and invention, themselves limited by … ‘the political ontology of the present’ ” (1998: 37).

Unlike the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse 6, then, whose alleged aim and purpose was to reveal the truth of the abuses that have occurred in Irish Catholic institutions over the last century or so – and which, many have argued has been largely unsuccessful in bringing about justice – my work aims to bear witness to lives lived in what has ironically been called ‘care’, and to do this by taking a genealogical approach to the “vast [and heterogeneous] accumulation of source material” (Foucault, 1984: 76) that speaks of and to this complex issue. Thus I want to maintain the idea of an “historical vacuum” – as suggested by Smith (2008) and Luddy (1995) – but to put something of a twist on it. In the Aristotelian sense, the word ‘vacuum’ means a ‘place bereft of body’. Rather than thinking of this as an absence, a place in which ‘evidence’ is missing – much like a crime scene without a corpse – I want, instead, to suggest that whilst the physical bodies of the many thousands of women known as Magdalens may not be available for forensic examination, material traces of their lives nevertheless remain. These traces are not, I contend, clues that will lead us to the truth; that will bring about closure. They are, instead, traces of ‘alterity’, of an otherness that one cannot know, but to which it is possible, nevertheless to testify.

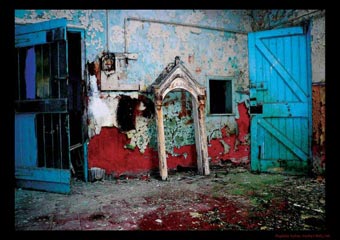

The images that you see here, the notes from my fieldwork diary, and the concluding ‘imaginary’ account of two Magdalens from Sunday’s Well in Cork, constitute one attempt to develop “disorderly and tattered genealogies that reactivate local knowledges … against the scientific hierarchicalization of knowledge and its intrinsic power-effects” (Foucault, 1975: 10). Each of these is, of course, informed by a vast array of sources that have shaped this project: from acts of parliament to autobiographical accounts of life in laundries and industrial schools; government reports to religious tracts; architectural plans to residential practices and protocols; political cartoons to the mission statements of various welfare agencies; the writings of activist groups to my own experiences of growing up in care in Ireland in the 1980s and 90s; and more recently in the winter days spent walking through and photographing the crumbling architecture, capturing the traces of lives that once passed through those places.

Notes from my Fieldwork Diary: Ireland, Jan 6 - Feb 4, 2010

I try to do things that involve a personal commitment that is physical and real, and which poses problems in concrete, precise and definite terms in a given situation (Foucault, 1978: 24).

In the winter of 2010 I returned to Ireland to embark on the photographic component of my research project. Ten years had passed since I had last been ‘home’, and I knew that during my long absence the institutions I wanted to explore would no doubt have changed considerably. Within days of arriving three significant events occurred which, along with the material I had been immersed in prior to my trip, shaped my practice in the field in profound ways.

These events were firstly, the discovery of the complete disappearance of St Anne’s Girl’s Home in Kilmacud where I was committed as an adolescent; secondly, the retrieval of my records from Our Lady of Charity archives 7 in Sean McDermott street in Dublin; and finally the global financial crisis which had manifested itself in Ireland through the abrupt cessation of the construction industry, which included the demolition and refurbishment of much of Ireland’s former ‘architecture of containment’. The significance of these events lay in the fact that each, in different ways, posed a challenge to, and ultimately undermined, the search for origins which I now, following Foucault, associate with ‘progressive history’ (as a metaphysical and meta-historical practice). If I had once thought that visiting the institutions in which abuse occurred, or obtaining the records of my internment might furnish me with truths that would lead to liberation, I was to be sorely disappointed.

In the days that followed these events, and in particular the evening after returning from a photographic shoot of the Sean McDermott St laundry where I had managed to unearth old tins of starch from abandoned demolition rubbish piles and discover old rosary beads still hanging above gargantuan Aga stoves in the darkness of boarded up Magdalen kitchens, that I began to re-read the notes that I had made prior to my trip. In doing so I came across an interview with Foucault that would be integral to the development of my fieldwork practice. In this interview J. J. Brochier says to Foucault:

Your researches bear on things that are banal, or which have been made banal because they aren’t seen. For instance I find it striking, that prisons are in cities and yet, no on sees them. Or else, if one sees one, one wonders vaguely whether it’s a prison, a school, a barracks or a hospital”

… to which Foucault responds:

to make visible the unseen can … mean a change of level, addressing oneself to a layer of material which had hitherto had no pertinence for history and which had not been recognised as having any moral, aesthetic, political, or historical value” (1980b: 50-1).

As I criss-crossed through the Irish countryside, I found and photographed the hidden remains of former asylums, laundries, reformatory schools, industrial schools and mother and baby homes, and all the while the conversation between Brochier and Foucault (cited above) played round and round in my head, shaping not only what I saw, but how I saw. But what I saw, and how I saw, what I photographed, and what I didn’t, what moved me, and what escaped my attention, was also an effect of my own history, and of the fact that I was now occupying the roles of both former resident and researcher.

Being placed at the intersection between ‘skilled observer’ and ‘social participant’, between the written conventions of scholarly engagement and personal memoir, between the methodologies of ethnography and autobiography, between a gaze that was simultaneously ‘inward’ and ‘outward’ in its direction and perspective, it became increasingly apparent that my project to develop “disorderly and tattered genealogies that reactivate local knowledges” (Foucault, 1975: 10) would inevitably be auto-ethnographic. Auto-ethnography, at least as I understand it, is a response to the crisis of metaphysics and the ideals with which it is associated (for example, truth, the humanist subject, objectivity, rationality, scientificity, and so on). Rather than unifying or totalising the contingent in overarching (and allegedly objective), narratives of truth, auto-ethnography acknowledges its own situatedness, it uproots, disrupts, fragments, metaphysical narratives in its focus on the fragmentary, identity, heterogeneity, sensuosity, affect, non-linearity, reflexivity, imagination, invention, complexities and ambiguities, gaps and proliferations, absurdities and limits. As Norman Denzin writes, life is:

lived through the subject’s eye, and that eye, like a camera’s, is always reflexive, nonlinear, subjective, filled with flash-backs, after images, dream sequences, faces merging into one another, masks dropping, and new masks being put on (Denzin cited in Ellis, 1997: 125).

Before making my way to the remnants of the Good Shepherd Laundry, I paused with camera-in-hand on the quays in the city of Cork and looked across the river Lee to the steep incline of Sunday’s Well. From this vantage point I could easily imagine the Magdalen women being taken across the bridge in a covered carriage drawn by horses as it made its way to the network of containment, the citadel of piety, which sits on the hill as a constant and formidable reminder to the inhabitants of the city below to mind their morals or else suffer the consequences. But what I found so much harder to imagine as I stood beside the roar of that great swollen river which divides the city in two, is a time when there would have been empty rolling hills, open and wild, with the promise of a wider world beyond. Shifting my perspective by drawing closer to the foot of the hill, I saw, leaching out beneath an imposing edifice of convent, laundry, mental asylum, industrial school and church, a labyrinth of avenues and dead-ends, the once green expanse now burdened beneath the scars of a parasitic affliction.

Once you enter this phrenetic system, the vast complex above your head disappears and you are swallowed whole, like Jonah, or a penitent, into the belly of a whale. The pitted and thinly tarred narrow roads of another century force you to negotiate the space between ancient mossy walls and the wing mirror of a 2010 Mercedes-Benz. The difficulty of making my way to the Magdalen site had caught me unawares given my earlier view from the quays. But what I found as I navigated the incline was a constant succession of sharp angled turns and a one way system of traffic, all of which was compounded by the absence of street names and sign posts. Eventually I turned into the car park of a 24/7 spirituality centre and it was from there, behind a bush, behind inhospitable wire and a sharp pronged perimeter fence, that the unkempt avenue leading to the laundry finally appeared.

Beneath a freezing-cold slate-grey sky, I walked along the overgrown and rubbish-strewn pathways between the convent and the dormitories, between the kitchens and the bakery, and from the mould-streaked bathtubs to the now-cluttered nuns cells. Finally, I thought, I am tracing the steps of Ireland’s disappeared. I spent the entire day within this hidden site, completely alone except for the stark and eerie cry of seagulls circling overhead as they no doubt did during the decades in which Sunday’s Well was peopled with penitents. Despite their disrepair, the buildings still held the power of stories yet to be told: the banisters worn by the touch of so many hands red and raw from the years of scrubbing; the door handles rubbed smooth by those denied the right to privacy and the countless layers of peeling paint revealing traces of lives once lived surrounded by that colour. As the clouds moved in from the West, the gutters began to leak and water cascaded down the dampened walls that had once functioned to keep in not only the detritus of society, but more particularly, the stories that must never be told. And as the rain came over, there came with it an urgency as the gaudy wallpaper, more befitting of a 1970s Carnaby Street pad than an institution designed to reform (or was it to punish?) ‘fallen women’, fell away in strips. The shame of Ireland’s disappeared is spirited away behind formidable fortifications, being allowed to fade – or so I imagine – as slowly and as imperceptibly as the silent clouds above.

When the light began to slip behind the city, I started back down the avenue and away from Sunday’s Well, where my perspective of the buildings changed once again. What I saw was the close proximity of the city’s local gaol which I realised shared with the laundry a perimeter wall topped with angry loops of rusted barbed wire. The gaol which still functions today and houses male inmates, had chartered buses parked along the road out the front. I was told by a local man on his way to the golf club that the goal was something of a local attraction. Hence the abundance of signposts giving clear directions to the prison, but making no mention whatsoever of the laundry that no one seems to see, or of the women who the Irish authorities hoped to banish from view, and progressive history conspires to keep hidden. If I had have known this when looking for the laundry earlier that morning, I should have simply asked for directions to the gaol.

On this very hill in Sunday’s Well in 1872, two penitents, Mary McMahon and Catherine Ahern began what was to become a combined sentence of 112 years behind the imposing laundry walls. On July 29 1922, to mark their golden jubilee as penitents, both women were granted a day of freedom: a rare and unprecedented gesture on behalf of the Good Shepherd Order. It was an occasion which was never to be repeated. On that first and only day outside the walls they were invited to the house of the Mother Prioress in Clifton, Co. Cork and “were returned that same evening laden with presents and greatly refreshed and gratified with their visit” (The Cork Annals 1922, cited in Finnegan, 2004: 24). Six years after this momentous occasion, Mary and Catherine, now aged 72 and 83 would die within four days of each other.

Casting my mind’s eye back to that summer’s day in Cork in 1922, I wondered how Mary and Catherine felt as they walked out of the asylum gates: did they reminisce about their youth when they saw a place they recognised or were they awestruck into silence as they witnessed the changes that half a century brings? One can only imagine how they felt, and the thoughts that went through their minds.

Mary and Magdalen of Dolours

Finally, thought Mary of Dolours, the harsh winter has taken its leave and the proof of it lay strewn around the leather of her slippers. The bluebells and the crocuses had, at last, broken free from the darkness of the earth and now a glorious multitude of yellow and purple reached towards the watery spring sun as it gathered in its heat. Despite her failing sight, Mary had watched and waited over the years for their returning and noticed for herself that the purple was at its brightest this time of year, because it was the purple that always seemed to shine its best whenever the rays of the sun were weak and shady. But of all the flowers that returned to her so faithfully it was the clusters of snowdrops that lined the path between her dormitory and the bake-house that she loved the most.

There was something in the way they bowed their heads that always drew her eye and made her ponder. There was a meekness that they possessed, but now, in recent years, she had come to recognise a quiet strength, a determined will, for now it was the 56th season that they had sprung-up on this side of the wall. The startling white of their heads cut through the confusion of her eyes, and it never ceased to amaze her, the purity of it coming from the dirt. It was the sort of white that Mary had dedicated her life too, the kind of white that does away with the darkness.

Shuffling carefully to the bench attached to the bakery wall, one by one Mary unfolded and settled each of her bones until she slumped into the relief of sitting. Such a simple thing, but the joy of it washed over her body and as she sighed she gave thanks to all the saints in heaven. For years herself and Magdalene of Dolours would come and sit in this very place during half-hour recreation. The young girls from the Industrial School, whom she never saw would be busy inside baking loaves for the community, and with the rattle and scrape of paddles and trays she could imagine how they’d look busy at their work, while the smell of their labour would fill her to the brim and give her the world of comfort. But today, of all the days she’d known, and the world, the only world she knew, was only ever going to be half of what it ever was, for Magdalene, her Maggie, had taken it with her when she left three days before.

Waking up to this beautiful day, the thinking wouldn’t leave her alone; she could feel her thoughts both turning in her head and turning back in time. So long ago, fado, fado, Mary had been unfortunate enough to be picked up by special constable for “going with men.” The constable, a self-righteous sort of man, marched her through the back streets of the city to the government run Lock Hospital. And it was there, to her great shame and to her greater terror, that they said she was diseased. The surly matron took it upon herself to inform Mary, that until she was cured, the cut of her and the likes of her would not be allowed to traipse the streets. Six long months it took for the medicine to do its work, and then one evening when night had fallen, she was taken across the Lee and up the hill of narrow lanes to the door of the Good Shepherd’s. Her name, Mary McMahon, was the first to mark their book, and the last time that it would be used, as it was from that night she’d be known as Mary of Dolours. And from that night they were true to their word, for she would never see the streets again for another fifty years. Almost three weeks to that night a spirited Catherine Ahern was escorted through the gates and from that day onwards she was known as Magdalene of Dolours.

And so it was from that July, both Mary and Maggie made their world within a world. All manner of girl came and went, while fresh-faced novices replaced the older nuns who died. Days and decades were soon dissolved as they scrubbed their sins away, always remaining steadfast by their sinks and by each other. It was to be the patina of a history and a life of mundane labour which would bind them inextricably together. But what was there to show for it now, thought Mary to herself, except for what lay across the way beneath a gently sloping mound of freshly dug-up earth.

Looking down at her hands on the coarse material of her tunic, with her knuckles thickened and gnarled with arthritis, she thought of Maggie. She wanted to tell her that there is no such thing as a clean brown, only a muddy one, and that their lives had been wasted in washing the greys and browns away. There is no such thing as a brown light, not now since the light went out in her beautiful brown eyes. Ashes to ashes, dirt to dirt, the meek shall inherit the earth, and the earth shall reclaim the meek.

References

Brown, W. (1998). Genealogical Politics. In J. Moss (Ed.), The Later Foucault. London: Sage.

Conlon, D. (2010). Ties That Bind: Governmentality. The State and Asylum in Contemporary Ireland. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28(7), 95-111.

Crowley Una, R. Kitchen (2008). Producing “Decent Girls”: Governmentality and the Moral Geographies of Sexual Conduct in Ireland (1922-1937). Gender, Place and Culture, 15(4), 355-372.

Danaher, G T. S., and J. Webb. (2000). Understanding Foucault. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Ellis, C. (1997). Evocative Autoethnography: Writing Emotionally about our Lives. In W. G. Tierney, Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Representation and the Text: Re-Framing the Narrative Voice (pp. 115-140). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Finnegan, F. (2004). Do Penance or Perish, Magdalen Asylums in Ireland. New York: Oxford University Press.

Foucault, M. (1980a). The History of Sexuality Volume 1: An Introduction (R. Hurley, Trans.). New York: Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1980b). Truth and Power (C. Gordon, Trans.). In Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977 (pp. 109-133). New York: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1984). Nietzsche, Genealogy, History. In P. Rainbow (Ed.), The Foucault Reader. New York: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (2007a). Security, Territory, Population New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, M. (2007b). Society Must Be Defended. London: Penguin.

Gatens, M. (1996). Imaginary Bodies: Ethics, Power and Corporeality. London: Routledge.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Priviledge of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies 14(3), 575-599.

Holt, N. L. (2003). Representation, Legitimation and Autoethnography: An Autoethnographic Writing Story. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(1), 18-28.

Inglis, T. (2002). Sexual Transgression and Scapegoats: A Case Study from Modern Ireland. Sexualities, 5(1), 5-24.

Kelly, O. (2003, 23rd August 2003). Order Says Magdalens Were Registered. Irish Times,

Lancaster, R. (2003). The Trouble with Nature: Sex in Science and Popular Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Luddy, M. (1995). Women and Philanthropy in Nineteenth Century Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Luddy, M. (1997). Abandoned Women and Bad Characters: Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century Ireland. Women’s History Review 6(4), 485-504.

McKenna, Y. (200). Entering Religious Life, Claiming Subjectivity: Irish Nuns, 1930s-1960s. Women’s History Review, 15(2), 189-211.

O’Malley, K. (1995). Childhood Interrupted. London: Virago.

Smith, J. M. (2008). Ireland’s Magdalen Laundries and the Architecture of Containment. Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press.

1 The words laundry and asylum are used interchangeably. As Ireland gained Independence from Britain, it became an increasingly dense spatialised grid of national bio-politics which became increasingly oppressive for Irish women and as a result the nature of the laundries evolved from sites of reform to sites of incarceration.

2 There were no death certificates issued for these women.

3 In his discussion of the traits of “effective history” as conceived by Nietzsche, Foucault includes the “affirmation of knowledge as perspectival”, and argues: “Historians take unusual pains to erase the elements in their work, which reveal their grounding in a particular time and place, their preferences in a controversy” (1984: 90).

4 I use capitalisation here to indicate that I am referring to a particular situated disciplinary practice, one in which specific conventions have not only been legitimised, but have, as a result, become naturalised

5 Here Foucault calls into question the use of the word ‘science’ and how is confers power to some modes of knowledge, privileging them over “non-scientific” modes of knowledge. Therefore, ‘genealogies’ are according to Foucault ‘antisciences.’

6 After more than a decade of investigations and witness testimonies relating to Child Abuse in State funded and religious run Irish institutions of care, the Ryan Commission finally published its findings in late 2009. However, in order to be eligible for compensation, a victim must have been resident in one of a number of specifically listed institutions; no Magdalene Laundries are included on this list and as such no compensation is deemed as needing to be forthcoming. See http://www.magdalenelaundries.com/news.html.

7 In February 2010 I received the records from my time in care from Our Lady of Charity archives in Sean McDermott Street in Dublin. For the six years I had spent in three different homes there were six pages in the report, most of which was repetitive and written by a social worker who rarely visited. My experience was akin to Kathleen O’Malley’s autobiographical account Childhood Interrupted, where she recalls her reaction on receiving her records from the convent of Mercy in Moate Co. Westmeath. She writes: “When I finally got my school records the most upsetting thing of all was how little record they had kept of me … the report on me in 1953, just over two years into my detention, simply says ‘troublesome and unreliable’” (2005: 227). In my own reports it was also interesting and telling as to what my social worker thought was worth reporting, for example she states that, “Kellie is drawn to masculine type clothes in men’s shops.” As Roger Lancaster writes, “Observation is an embodied, social, and collective art. [W]hat we see as an objective ‘fact’ will depend on a large number of subjective, constitutive, social acts. Even what counts as a phenomenon worth studying, as a result worth reporting, as a similarity of a difference – these are not self-evident in the nature of the world. They depend on what perspective one takes – or refuses to take” (2002: 67)

About the Author

Kellie Greene is a PhD candidate in the School of Communications Arts at UWS. Her article is part of a wider project entitled Remembering and (Re)Presenting Lives Within Care. It draws on her own experience of living within the Irish system of care and incorporates a creative photographic component which involves returning to Ireland to record various sites of that system which are gradually disappearing from the Irish landscape.

Contact Details

Kellie Greene k.green@uws.edu.au