Interpreting Tongan Mythology for Contemporary Youth

Interpreting Tongan Mythology for Contemporary Youth

— University of Western Sydney, Australia

Abstract

This paper outlines a personal project that aims to capture the essence of Tongan myths and legends through the graphic novel form. The stories have been linguistically translated (from Tongan to English) and adapted from ‘Efinanga (1994), a text compiled by my late grandfather, Masiu Moala. ‘Efinanga (1994) contains over 80 myths and legends and expresses my grandfather’s passion for upholding Tongan culture and the need to pass these tales on to Tongan youth. The challenge for the creative work has not only been to remain true to these ideals, but also to communicate the story in a way that speaks to the youth of the Tongan diaspora and to visually literate, multicultural youth more broadly. The uniqueness of the graphic novel form lies in the juxtaposition of images to communicate a story, which not only responds to the target audience's preference for visual media, but can also help reclaim the rhythm and dynamism of oral traditions of storytelling. This essay tells the story of the evolution of my creative work through an engagement with literature and graphic precedents and Tongan cultural history as well as primary research conducted in Tonga. Through this project, I have discovered the richness of Tongan cultural history and found a way to contribute to it in a contemporary context.

Graphic novel form

To appreciate the complexities of this medium, the works of Scott McCloud and Will Eisner are invaluable. In his book Understanding Comics (1993), McCloud defines comics as “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence” (9). As will be uncovered, it is the juxtaposing of images in sequence, and not images themselves, that constitute the key function of comics. As maintained by Eisner, McCloud explains that perhaps the best definition is “sequential art” (9).

Manipulating how readers perceive time and space is a skill that comes from understanding how image and word work together to tell a story. Duncan and Smith (2009) argue that there is a particular kind of literacy that must be tapped into when reading sequential art.“In general,” they write, “the comic book reader begins building meaning from the images within a panel and moves outward to the panel as a whole, panels in relation to other panels, the page, the story, and how the story, in some cases, fits into an ongoing narrative continuity” (154). It is important to note that what artists include and exclude from comic panels influence how the story is read. McCloud (1993) accounts for this when he explains how the gutter – space between panels – is reminiscent of playing a game of peek-a-boo (67).

Comic book creators make particular choices and utilise various techniques to effectively weave together stories that inform or entertain. In his book Making Comics (2006), McCloud discusses five significant considerations that can “make the difference between clear, convincing storytelling and a confusing mess” (10). The artist’s choice of moment, frame, image, word and flow affect how the story is read. Choosing the right moment to depict within panels involves picking the events or actions you want to show or leave out. These ‘moments’ can then be displayed from varying angles or distances (which can be reminiscent of filming techniques, for example, establishing shots and close-ups). Appropriate image choice is vital to creating engaging characters, objects and environments within frames. Written text, involving size, style and content, imparts valuable information and complements the chosen imagery. Finally, choice of flow determines how readers are guided through and between panels on a page. Flow is determined by how panels are drawn, their size and where they are placed on a page. These considerations have helped inform how the visual analysis of previous work is carried out as well as guiding the experimentation and development of my creative work.

Vital to communication and storytelling is understanding who is listening or reading. As indicated, connecting with a young contemporary audience demands particular considerations. As a result of high media saturation, readers are accustomed to receiving ideas, information and stories quickly. Whilst images in print and film transmit with the speed of sight, film is a medium that orders the experience of the audience through mechanisms of editing (you watch what you have presented to you: the frame ‘disappears’ in the illusion of live action). In contrast comics reveal the past, present and future of a narrative concurrently (that is, comics hold together form and content/ sequence and composition/ the temporal and spatial). In this case, the reader has the ability to control the order and timing of the narrative. This leads to the dual concepts of attention and retention. As Eisner suggests, “[a]ttention is accomplished by provocative and attractive imagery. Retention is achieved by the logical and intelligible arrangement of the images” (Eisner 2008, p.51). Therefore, experimenting with sequence and composition should help determine the appropriate rhythm of the graphic story: which elements draw attention and which arrangements retain it.

At the storyteller’s disposal is the ability to induce empathy. Eisner (2008) explains that “empathy is a visceral reaction of one human being to the plight of another. The ability to ‘feel’ the pain, fear or joy of someone else enables the storyteller to evoke an emotional contract with the reader” (47). As with traditional paintings, the colours, materials, and artistic style employed by comic creators enhance narrative content and can draw emotional responses. (Basic examples include the colour red suggesting passion or danger or watercolour paint emphasising tranquillity.) Rachel Marie-Crane Williams (2008) claims there is a link between autobiographical graphic novels and establishing “human connectedness” (15). With reference to Maus (1986) by Art Spiegelman, Persepolis (2004) by Marjane Satrapi, and Palestine (2001) by Joe Sacco, Williams claims, “it is impossible for readers not to feel some sense of empathy with the main characters and conflicts they endure and witness … [readers] step into the eyes of another and consider a different point of view” (15). When reading sequential art, it is the aesthetic experience one is involved with that allows the audience to live new experiences and feel the emotions the author wants us to feel. Due to the personal nature of my project, it was highly advantageous to explore how the graphic novel has been used to express intimate biographies.

Auto-ethnography in the graphic novel

Maus (1986) is a renowned graphic novel by Art Spiegelman that tells of living through and after the Holocaust. The story is split into two parallel narratives. First, Spiegelman is a character within the plot asking his father, Vladek, about his experiences during Nazi occupation of Poland. Second, flashbacks are visually depicted detailing what Vladek and his wife, Anja, went through during the Holocaust. Perhaps the most distinct graphic device utilised by Spiegelman is the anthropomorphism of animals. Jews are portrayed as mice, Nazis as cats, Poles as pigs, Americans as dogs and the French as frogs. By employing this graphic device, Speigelman wanted to make a comment on Hitler’s rationale for the Holocaust: that Jews were not truly human. Consequently, comparing Jewish vulnerability to that of mice enhances the horrors of Nazi treatment of the Jews.

Joe Sacco’s Palestine (2001) tells of Sacco’s visit to Israel and the occupied territories of Palestine over the span of two months. As a prominent practitioner of the genre of comic book journalism, the narrative consists of a combination of eyewitness reportage with illustrated footage of his interviews. Sacco’s visual style functions as a representational device that conveys the turmoil in the Middle East. His use of exaggerated human form, detailed illustrative work, rough panels, text placement and montage demonstrate this point. These techniques enforce a fluid and dynamic style that makes for engaging artwork. As a result, both the graphic style and the content of the accounts confront the reader.

As made clear by McCloud in Understanding Comics (1993) and Making Comics (2006), there are particular choices that artists make that affect how a narrative is read. As Versaci writes: “Sacco draws himself in a much more cartoonish and exaggerated manner than the others around him, and this strategy causes him to stand out as someone who doesn’t quite 'fit' into this landscape or with its native habitants" (2008: 119). To highlight this point further, the opening page of each chapter shows a scene from the story where Sacco depicts himself in bold relief against a faded background; this accentuates his presence as an 'intruding agent’ in the lives of these people and reminds readers that he is filtering the events through his own individual perspective (Versaci, 2008: 119). It is through the alienation of Sacco that the act of ‘witnessing’ becomes most prominent for the reader.

In a similar narrative style, Persepolis acts as a memoir of Satrapi’s experiences. The publication consists of two volumes: The Story of a Childhood and The Story of a Return, recounting what it was like growing up in Iran during and after the Islamic revolution. This touching autobiography balances humour and earnestness to tell a story about the impact of youth displacement on the resilience of cultural tradition. Acknowledging these issues, which also affect Tongan youth, as a thematic in the graphic novel has influenced my own practice-based research. The monochrome artistic style utilised is simple in terms of line and shape which complements the comical aspects while leaving room for use of symbolism and metaphor. Versaci (2008) believes that Satrapi’s style sustains the vivid imagination and fantasy life of her early years. The visual style forms “a crucial part of the comic book memoirist’s first-person narration” (46).

Tonga

Inevitably, the project must be placed within a geographical, historical and cultural context – that of Tonga. This Pacific island is my country of origin. Ruled by a king who overlooks a party of nobles and parliament, most of the commoners practice a “simple, subsistence agricultural lifestyle on which the economy of the country depends” (Cartmail, 1997: 17). Despite modernisation, Tonga retains a close connection to its traditional culture. Its people are proud of their customs and are dedicated to preserving them and passing them on to future generations. Until British missionaries arrived in the 18th century, the Tongan people believed in a rich mythology of gods and creatures. Since then, these stories have been somewhat confined to dated academic writings.

“This book is intended for the use of secondary schools in Tonga …” These words appear in the author’s note of History and Geography of Tonga (1932) by former principal of Tupou College A.H. Wood. The text exhibits a handful of Tonga’s myths by detailing the Royal lineage, however, the book’s report style format fails to engage on an aesthetic level. Perhaps a victim of its time, although the stories displayed may be timeless, the medium is limited in conveying a message that is contemporary. Even so, there is more to Tonga’s history than what is written.

Tongan culture is primarily an oral one: “Through myths, legends and genealogies Tonga possesses a storehouse of oral tradition from which some aspects of its history since about A.D. 1000 – the Classical Tongan Period – can be reconstructed” (Rutherford, 1977: 27). Noel Rutherford purports this in his book Friendly Islands: A History of Tonga (1977). The text charts a comprehensive account of the key events in Tonga’s history. However, again, while this publication delivers valuable and relevant information, it typifies a scholarly form of communication that would be unlikely to engage Tongan youth. This can be attributed to literacy issues as well as the understanding that visual media tend to be more appealing to youth.

Oral and visual storytelling are parallel activities that have developed over centuries – from ancient times to today. The question is can an oral culture be translated into a graphic form? Notably, the base text has, to some extent, lost the rhythm and dynamism of spoken language. Through experimentation, content and composition will be manipulated to take advantage of sequential art’s distinct features. Thus, by combining word and image as embodied by the graphic novel, I hope to return to the stories some of this lost rhythm and dynamism by visually interpreting Tongan mythology and revealing it to a receptive audience. Like Maus and Palestine, a cultural context supports characters and story that invoke empathy from the audience. The creation of a graphic novel will provide a rich source of information in the field of education especially for the Tongan diaspora. Readers will gain an understanding of the history of Pacific island culture from a relatable and modern source.

Pre-production

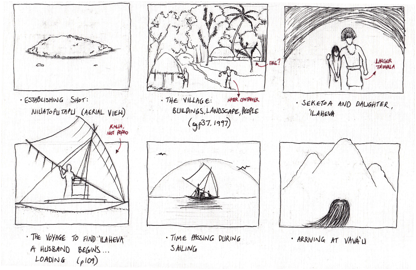

Prior to the production process, issues of cultural authenticity, establishing a need, and embedded meanings within mythology must all be addressed. These factors were investigated through on-site unobtrusive observations and semi-formal interviews. Imagery generated for the publication must be true to the time period in terms of the appearance of people, costume, landscape and artefacts. I visited Tonga in July 2010 to conduct studies in the form of photography and sketches (Fig.1).

Travelling to the locations indicated in the chosen story greatly increased my appreciation for elements within the narrative: colours, forms, textures and sounds. In addition, trips to other spots perceived as useful were made, including the Visitor’s Bureau, National History Museum, and family plantation.

Community leaders are important role models within the Tongan populace. They inform and guide the people through social and political issues. Interviews were conducted to garner the current attitude towards storytelling, mythology and Tongan culture. Participants were chosen for their differing expertise in their particular fields. Kalafi Moala (Tonga) possesses insight acquired from his work as a journalist (editor-in-chief) for two newspapers, TV and radio. Sione Havea’s (Parramatta) position as a lecturer and coordinator of the Talanoa Oceania conference provides insight into the state of second-generation Pacific islanders and the notion of ‘talanoa culture.’ Finally, Rev. Siupeli Taliai (Melbourne) is a modest, yet esteemed authority within the Tongan community. He has specific knowledge and awareness gained from working as principal at Tupou College in Tonga and a minister for the Uniting Church. These three men agree and disagree on certain issues concerning the project so it must be noted that each individual carries a particular bias. However, the level of knowledge and understanding they each provided validates the importance of this project.

The interviews, together with journal articles, also helped affirm the needs of the target audience.

Young Tongans, born and bred overseas, need to be exposed to Tongan culture early in life in order to minimise the negative effects of an ‘identity crisis’. They need to learn about their Tongan identity by speaking the Tongan language, learning the protocol, becoming familiar with their history, and knowing their roots early in life. They may then take pride in their culture, and may make the best choices offered by the two worlds they live in (Samate, 2007: 47).

As a second generation Tongan with a personal awareness of the importance of culture and storytelling (which can be attributed to my parents and grandparents), my connection to the subject matter greatly influences the creative work: childhood memories of bedtime stories, the passing on of fables from generation to generation and an ingrained oral tradition influenced by history, culture and spirituality. These elements are exhibited within the conceived graphic novel.

Production

The following production process shows the fluid and trial-and-error nature of practice-based research. ‘Efinanga (1994),the legend of ‘Aho’eitu, Tonga’s first king, was chosen because of the values it has instilled within the Tongan people: respect towards royalty, a distinct hierarchical social structure, and a need for spirituality. The chosen interview participants confirmed these notions. The crucial first step in the creation process after a myth was chosen, was the analysis, interpretation, adaptation and evaluation of the narrative to be visualised.

A script was extracted from the translated and adapted story of ‘Aho’eitu and then a storyboard was produced to reveal the key scenes within the myth to be told. This procedure assists in the editing and framing of the narrative as it allows the producer to determine which events to focus on and those that can be discarded or understated. Scenes that were more important than others and events that may affect the pacing of the narrative were taken into account.

Preliminary storyboarding also enables the producer to refine the depicted features. As shown in fig. 2, these corrections were done with the guidance of my father. Additionally, this first page of the storyboard shows how the opening scene requires a stronger emphasis on location. As a result, a number of panels are needed to show readers the environment in which the narrative is set (Fig. 2).

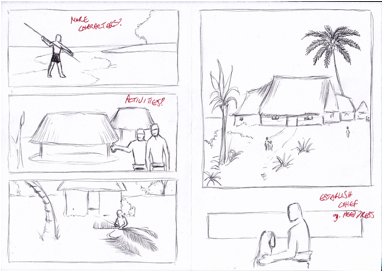

A second form of storyboard was then created to determine the final panel composition and also the framing. This showed that more detail will be required in terms of panel content, size and placement (Fig. 3).

The decisions were based on what was perceived as most appropriate for the narrative. In regards to pace and emotion, panel layouts are key. As alluded to by McCloud (1993 & 2006), the variations are endless, but specific arrangements communicate particular messages to the reader. Fig. 4 shows panels in their pencil stage from my creative work. They convey how action can be displayed through several compact panels and also by not constraining a subject to a panel’s borders.

I then evaluated and adjusted the length and timing of events and this then led to the creation of final pencil drafts, which comprise all the details to be included in the final graphic novel.

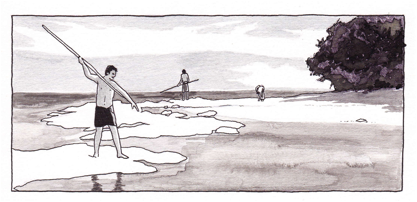

Once the pencil drafts were completed, inking commenced. At this point, it had been my intention to experiment with inks as well as watercolour paint to determine an appropriate aesthetic that would complement the narrative and pencil art. Furthermore, as time constraints would also affect the choice of colouring technique and so I chose whichever approach time would allow. After deciding that most of the narrative would be rendered in pen and ink, I undertook a process of trial and error to establish a consistent and appealing aesthetic. I chose Black India ink for its water-based qualities in order to effectively depict the ocean and sky as well as allow a distinct tonal characteristic to come through (Fig. 5).

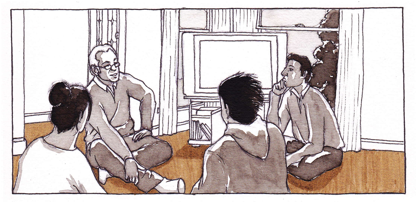

As with the illustration style itself, consistency in the inking technique was difficult to maintain. However evaluations and remakes were carried out according to my own revised judgements. I decided that the best way to make the narrative more accessible to modern youth was to establish a contemporary setting at the beginning and end of ‘Aho’eitu’s story: a family gathering where a grandfather relates the legend to a group of young people (Fig. 6). This concept indicates links to oral tradition, the passing on of stories and on an autobiographical level, reflects my own childhood. Emerging out of practice-based research was a way of differentiating between the storyteller and the story itself through slight colour variations.

As asserted by Barbara Bolt (2006), there is a “double articulation between theory and practice, whereby theory emerges from a reflexive practice at the same time that practice is informed by theory. This double articulation is central to practice-led research” (4). This was evident throughout production.

Conclusion

By combining an understanding of how the graphic novel functions, and by interpreting visual and textual precedents and the issues affecting Tongan culture and people, one can uncover the appropriate response to the problematic: How can Tongan myths and legends be made relevant through the graphic novel form to a young contemporary audience? Examination of the field of sequential art has revealed how prominent practitioners can and have executed storytelling techniques. The success and popularity of Maus, Palestine and Persepolis confirm the status of the graphic novel as an effective conveyor of story. These texts support Duncan and Smith’s assertion that “[comics have the] ability to help build a given culture’s identity and the propensity they have to build bridges between cultures are but two more manifestations of the power of comics.” (313)

Researching Tongan culture through literature has exposed the richness in history and tradition of the Tongan nation. It is crucial to communicate these origins to the next generation in a way that is engaging and long lasting. Adrienne L. Kaeppler argues that the arts do not just reflect social activities but help construct cultural values (66). This venture not only anticipates the preservation of Tongan stories, but also the historical and cultural values they stand for. The uniqueness of the graphic novel form lies in the juxtaposing of images to communicate story, which not only supports the target audience's preference for visual media, but can also help reclaim the rhythm and dynamism of oral traditions of storytelling.

List of images

Fig. 1: Reference photo taken in Pangai Motu, Tonga (2010)

Fig. 2: Preliminary storyboard, page 1 (2010)

Fig. 3: Secondary storyboard, page 3 (2010)

Fig. 4: Final pencils for creative work, page 24-25 (2010)

Fig. 5: Inked panel from creative work, page 4 (2010)

Fig. 6: Inked panel from creative work, page 33 (2010)

References

Bolt, B. (2006). A non standard deviation: Handlability, praxical knowledge and practice-led research Speculation and Innovation: Applying Practice Led Research in the Creative Industries Conference RealTime Arts (Vol. 74 August-September, pp. pp. 1- 15). Australia: Queensland University of Technology.

Cartmail, K. S. (1997). The Art of Tonga. Australia, United Kingdom: G + B Arts International Ltd.

Duncan, R, Smith, M. J. (2009). The Power of Comics: History, Form & Culture. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Eisner, W. (1985). Comics and Sequential Art. Paramus: Poorhouse Press.

Eisner, W. (2008). Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc.

Kaeppler, A. (2007). Heliaki, Metaphor, and Allusion: The Art and Aesthetics of Ko'e 'Otua Mo Tonga Ko Hoku Tofi'a." In E. Wood-Ellem (Ed.), Tonga and the Tongans: Heritage and Identity. Melbourne: BPA Print Group.

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Northampton: Tundra Publishing.

McCloud, S. (2006). Making Comics (1st ed. ed.). New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Moala, M. (1994). 'Efinanga. Tonga: Lali Publications.

Rutherford, N., ed. (1977). Friendly Islands: A History of Tonga. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Sacco, J. (2001). Palestine. Seattle: Fantagraphics.

Samate, A. (2007). Re-Imagining the Claim that God and Tonga are my Inheritance. In E. Wood-Ellem (Ed.), Tonga and the Tongans: Heritage and Identity. Melbourne: BPA Print Group.

Satrapi, M. (2006). Persepolis. London: Jonathan Cape.

Spiegelman, A. (1986). Maus. New York City: Pantheon Books.

Spiegelman, A. (1991). Maus II. New York: Pantheon Books.

Versaci, R. (2008). This Book Contains Graphic Language: Comics as Literature. New York - London: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Wood-Ellem, E., ed. (2007). Tonga and the Tongans: heritage and identity. Melbourne: BPA Print Group.

About the Author

In the pursuit of his interests in art and design, particularly illustration, Netane Siuhengalu completed an Honours degree in Design (Visual Communication). His work is influenced by his cultural heritage of Tonga, Christianity and family as well as literature, film and art. Following completion of tertiary studies, he hopes to work in publications, advertising or education. He would also like to travel overseas.

Contact: n.siuhengalu@gmail.com