The social media cyber-war: the unfolding events in the Syrian revolution 2011

The social media cyber-war: the unfolding events in the Syrian revolution 2011

Abstract

This paper analyses how both the Syrian Electronic Army (SEA) and the Syrian Free Army (SFA) have engaged with social media networks, ‘cyber war’, ‘cyber-attacks’, disinformation and propaganda in the Syrian revolution of 2011. The importance of information dissemination during the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ revolution was crucial in determining the outcome of the revolutions. Unlike in Egypt and Tunisia, the Syrian regime restored the country’s internet connection during the uprisings and left restrictions on Facebook and other social media platforms in a move to trap social media activists and crack down on them. To understand the role of social media during the Syrian revolution, the paper firstly draws on the framework of the Syrian revolution, how it started and the regime responses. Second, it sheds light on digital activism before and during the revolution. Third, it explores the social media cyber-war, the directed cyber-attacks by SEA to the revolutionaries and other international opponents. The theoretical framework is drawn from an information warfare perspective. This article is based on self observation of the SEA and SFA on Facebook and Twitter accounts as both a member and a follower. Satellite channels have been used secondary resources as they were instrumental resources in the conflict.

Introduction

In the wake of the upheavals of the revolutions that became known as the ‘Arab Spring’ in late 2010 and early 2011, social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube were heralded as instruments that sparked, mobilised and coordinated the uprisings. Media outlets coined the terms ‘Facebook revolution’, ‘Twitter revolution’ and ‘YouTube uprisings’ to describe the prominent role played by social media. The Syrian revolution began on March 15, 2011 with demands for freedom and political reforms. Social media platforms however, had already played a key role in speeding up the downfall of both the Bin-Ali and Mubarak regimes in Tunisia and Egypt in early 2011. The Syrian youth have been inspired by the ultimate triumph of the Tunisian and Egyptian revolution that resulted in political change and promoted democracy. In this reflection I will cast a brief glance at the unfolding events of the Syrian revolution by focusing on the communication tools used by the revolutionaries from digital information technologies to pigeon post. The uniqueness of this revolution, compared to other Arab Spring revolutions, is that information communication technologies (ICTs) are being harnessed by both the Syrian regime led by the Syrian Electronic Army (SEA), and the Syrian revolutionaries led by the Syrian Free Armey (SFA). This has resulted in the first social media cyber-war. This article will look closely at social media cyber-attacks, disinformation, propaganda and surveillance as it is being used by both the (SEA) and (SFA) to win the online front – an operation that is having a significant impact on the offline battles. My reflections are based on a close monitoring of SEA and SFA Facebook pages, YouTube channels, twitter feeds and other resources such as news articles and satellite channels.

The spark of freedom

The ultimate triumph of both the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions has inspired many Arab youth to take up the challenge and ride the wave of the revolution. In Libya, Bahrain, Yemen and Syria, young people followed in the steps of their Arab peers and began demanding reforms and public freedom. Watching the growing wave of demonstrations across the Arab world, Syrian regime officials argued that such uprisings could happen anywhere but in Syria. But, why not in Syria?

Those who know the Syrian regime well would have a simple answer to this question. The Syrian regime has a long history of ruling the country with vicious repression. In the 1970s, former president Hafyz Assad (1971 - 2000) led the ‘correction movement’ and subsequently ruled the nation with an‘iron fist’. Even the Assad family name has attached itself to the country, leading to the now well-known moniker – ‘the Assad Syria’. During the rule of the Assad family, Syrians have been no better off than any of the other Arab populations. The authoritarian regime has brutally suppressed opposition, leaving no room for political opponents. Emergency laws have been imposed and citizens face daily indignities and humiliations. The Assad family belongs to the minority ‘Alawite’ sect which compromises nearly 15% of the population (75% are Sunnis and 10% are Christians). The Alawite sect controls all aspects of the political system, and the military, the media and economy.

The greatest opposition to Assad‘s regime has come from organised religious groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, culminating in the Muslim Brotherhood insurrection and the subsequent massacre of 25,000 to 40,000 people in Hamma in February 1982. However, there has also been opposition from intellectuals, professionals and activists from secular political parties. They too, have been harshly dealt with. The professional associations of lawyers, engineers and doctors were disbanded in 1980 and their leaderships imprisoned. And yet, even though many Syrians are afraid of Assad and of the secret security police (Mokhabarat), many are more frightened of what may happen in Syria without the Assad regime.

Syria‘s official opposition has not provided much hope as it remains divided and weak. The 2005 Damascus Spring, which consisted of human rights associations, political parties, civil society forums, intellectuals and underground Islamic groups, was fragmented and ineffectual. Self-censorship is the primary way of filtering information in Syria. In most of the state owned media, journalists are government employees who fear losing their jobs at any moment. The Syrian regime portrays itself in the Arab world as the ‘Arab resistance’ – al-mumana’a al- arabiyah – in relation to its position confronting the state of Israel. Unlike Egypt and Jordan, Syria has not reached a peace agreement with Israel even though the Golan Heights have been occupied by Israel since the 1967 war.

It has been said that not even a single gunshot has been fired at the Israelis during the rule of the Assad family; the myth of resistance has been effective propaganda to empower the regime that has been protecting the Syrian-Israel border and not claiming back the occupied Golan Heights. In breaking the international silence over the case of Syria, Laurent Fabius, the French foreign minister, released documents on September 1, 2012, endorsed by Alawite leaders (including Sulaiman Al-Assad the grandfather of Bashar Al- Assad), which contained pleas to the French government not to grant Syria independence due to fear of persecution from the majority Muslim Sunnis. The Alawite leaders at the time claimed that the Muslim Sunnis would kill them as the Palestinians and Arabs had killed and humiliated Jews before the declaration of Israeli independence in 1948. The release of this classified information has challenged the myth of ‘Arab resistance’ and mired the regime in scandal.

This lends some weight to understanding why the Syrian revolution has taken so long to eventuate. As an observer of this conflict, it is my sense that the Alawites, with the help of their allies (the Iranians and Hezbollah), will fight until the last shot to stay in power – even if the whole nation is destroyed in the process.

From the perspective of this historical context, this article will explore how Syrian activists have harnessed multiple communication technologies – including social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, Skype and Twitter, mobile phones (SMS, Record video and live stream), traditional face-to-face communication and even carrier pigeons – to achieve several aims. Namely, to expose the regime’s brutality to the world, communicate with other revolutionaries across the country, spread propaganda, coordinate military attacks, and to disseminate news and information about the revolution.

Social media and the Syrian uprising

On March, 15, 2011 the winds of the Arab Spring uprisings reached Syria. Inspired by the regime changes in Tunisia and Egypt, the youth of Darra (south) began to protest, calling for reforms and freedom. In Tunisia and Egypt protesters had demanded the end of the Bin-Ali and Mubarak regimes. However, the Syrian protesters’ main slogans were Selmyah, Horryah (peaceful, freedom). The Syrian regime responded to the peaceful demonstrations in Darra by opening fire and killing 200 demonstrators and detaining many hundreds more in an attempt to crush the call for reforms. In solidarity with the Darra killings, the protests snowballed and reached the city of Homs in the Northern Province. Homs has been called ‘the revolution capital city’. In Homs the regime used artillery and heavy weapons including air strikes to try to suppress the movement. Importantly, the protesters’ only retaliation weapon was YouTube, leading Khamis to describe the Syrian revolution as the ‘YouTube uprisings’ (Khamis et al, 2012). The high level of mobile phone penetration in Syria also played a pivotal role in publicising the regime’s brutality. The incidents in Darra and Homs were recorded and uploaded onto YouTube and broadcast worldwide. This was in stark contrast to the events of February 1982 when Hafez Al-Assad (father) committed a massacre in Hama, killing an estimated 25,000 to 40,000 civilians following the rise of the Islamic Brotherhood in the province.

In Hama 1982, local and international media were banned from documenting events. In Darra 2011, the killing of the 13-year-old boy, Hamzeh Alkhateeb, provoked international outrage after his battered, and clearly tortured, body was shown on a video that had been uploaded to YouTube. This was the first outbreak of active dissent on the internet in Syria for decades. Syrian activists had turned to Facebook, Twitter and other internet tools such as Skype and Yahoo Messenger live-stream to broadcast news and information about the uprisings. The first Facebook group page established to spread the word of the revolution was ‘We are all Hamzeh Al-Khateeb’. This page mimicked the famous Egyptian Facebook page ‘We Are All Khaled Sa’ed’, that had sparked the call for protests on January 25, and which marked an important turning point in Egypt.

In response to this social media activism, the Syrian government switched off mobile phones and Internet connections in Darra and Homs in an effort to hinder communication and the dissemination of news about the revolution. However, the communication tools of social media remained critical for the revolutionaries. In the first few months of the revolution they were seen as the only tools available for fighting and in the Egyptian case, it was noted that tweets were more effective than bullets (Faris, 2011). To restore communication technologies between revolutionaries in Syria, proxy modems, satellite phones and international mobile phones SIM cards were smuggled in from neighbouring countries. It has been reported that in Darra (south) that is only few kilometres away from the Jordanian border of Ramtha, Jordanian mobile phone SIM cards were used by the revolutionaries to reconnect, and in Idleip (north) Turkish mobile phone SIM cards were used. Smart phones and the access they provide to 3G wireless internet have also been a significant tool for the revolutionaries, so significant in fact, that the Syrian government has banned the use and import of iPhones into the country (BBC, 2011).

Al-thuraya Saudi satellite phones, powered by the Saudi Telecommunications Company, were also used to report news to international satellite channels such as Al Jazeera and Al-arabiya. Syrian tech-savvies also resumed their internet activism by using dial-up connections and proxy internet modems.

The power of social media in the early stages of the revolution has to date, achieved many things. It has raised awareness among the majority Sunnis of the extent to which the regime has been aided by Alawite civilians (shabehah) – non-military personnel from the Alawite sect who fight to protect the Alawite regime. Shabeha have committed massacres, rapes and looting. Facebook revolutionary pages such as ‘The Syrian Revolution 2011’ and ‘Like for Syria’ as well as YouTube videos have exposed their crimes. As a result, Sunni soldiers in Assad’s army have defected and established the so-called the Free Syrian Army (SFA).

There has been another achievement, too. After the revolution transformed into a militarised conflict, each fighting unit of the Syrian Free Army (SFA) established its own Facebook group and press centre which has led to the founding of the ‘Local Coordination Committee’ (LCC)’ – an organisation that disseminates news about military battle news to the international media. Their mission also included keeping a count of the number of killings, diffusing propaganda, and reporting to international agencies. Their role was productive in spreading fear among Assad’s military and in helping to facilitate defections. For example, when the ‘crisis cell’ or group of top government leaders known as the Khalyat El-azmah, were targeted on July 18, 2012 in a bomb attack assassinating several members of the group, the revolutionary media reported that Assad’s military abandoned their tanks and guns and fled for their lives. This propaganda raised the morale of the Syrian people and many hundreds of military personnel defected and joined the Syrian Free Army (SFA).

As a result of the government’s crackdown, social media in Syria have become the first source of news and Arab and international media now fully depend on citizen journalists. Professional journalists were banned from entering Syria, however a few international correspondents and photographers from the BBC and Al Jazeera were smuggled into the country across the Turkish and Lebanese borders and stayed for few days producing two documentaries: ‘The way to Damascus’ and ‘Syria songs of defiance’ by Al Jazeera (2011) and ‘Inside the secret revolution’ by the BBC (2011). Other reporters such as Mary Colvin and Remi Rolick were killed while many other citizen journalists have also been killed trying to report the conflict for international agencies.

On May 2012, Bashar Al-Assad expressed his anger on a visit to the national Syrian TV. He condemned social media and pronounced that the revolutionaries were winning the space battle. In his words ‘we are winning the ground battles and they are winning the space, this is not fair, we are a state so that state media should verse state media not revolutionaries media’. Social media therefore has played a role in mobilising public opposition despite the militarized revolution. Street protests by both days in most of the country’s streets have been orchestrated and synchronized via Facebook pages and Twitter feeds. #Syria has played a role in these events by coordinated the protests and informing the world press. It has been reported on Al Jazeera satellite news hour that over 600 street demonstrations organized by social media platforms broke out in one day (Al Jazeera, 2012).

Other means of communications were applied in the absence of social media. The Assad regime cut off internet connections and mobile phone services to hinder activists’ communication. In some cases activists feared for their lives as the regime hunted them down with Iranian-supplied surveillance technology which could reveal their locations. The regime also used distributive denial of service attacks (DDoS) viruses to target websites and Facebook pages. In response, and with few other options available, carrier pigeons were used to deliver messages in the besieged province of Baba Amer in Homs. For nearly 40 days in a row, Baba Amr was besieged and heavily targeted by artillery and air strikes. A video uploaded to YouTube by Omar Tellawi, one of the most influential citizen journalists who played a major role in documenting the events of Baba Amr and the preferred contact person for Aljazeera and other satellite channels, showed how he had harnessed the homing pigeons as a medium of communication when all other communication channels were cut off by the Syrian regime. A message carried by one of the pigeons which read ‘in the name of Allah the most merciful, please send us food and medical aids through the eastern side of Baba Amr as it is clear from the Assad’s military presence’, was signed by the Local Coordination Committee (LCC) of Baba Amr.

The use of carrier pigeons in the digital age is variously significant. First, it highlights the importance of pigeon post during war time as illustrated by the major role played by carrier pigeons in both world wars. Second, its use can diminish the impact of surveillance and censorship: as mentioned earlier the Syrian regime applied sophisticated surveillance technology to crack down on online activists. The regime was neither aware that pigeons were carrying messages nor did it have hawks to intercept them as did the Germans during WWII. Third, the use of pigeon post could potentially change the way media theorists look at such ‘primitive’ communication mediums which have generally been considered ‘extinct’ or irrelevant in the age of the information communications revolution.

In addition, face-to-face communication and message delivery using motorcycles have also been widely used in Syria to evade surveillance. The SFA has used these methods of communication to coordinate attacks and deliver sensitive information to the Syrian National Council based in Turkey and vice-versa. It was reported by the ‘Syrian revolution2011’ Facebook group that the defection operation of late Syrian Prime Minister Ryad Hijab was managed by the SFA using only peer-to-peer communication.

Internet activism and the regime responses

Since the advent of satellite television in the 1990s, many more Syrians are watching foreign broadcasts. However, while the internet has also been available since 2000, it has a low penetration rate. The kind of issues covered on blogs and other internetInternet media remains to be canvassed by researchers.

Blogging activism in Syria started in 2004 when Ayman Haykal established his first blog on BlogSpot site using the title ‘damascene’ in English. A new site, ‘Syria Planet’, also authored by Ayman, became the official blog aggregator and portal for the Syrian community of bloggers later in 2005 (Taki, 2010). The Syrian regime monitors internet use very closely and has detained citizens for expressing their opinions or reporting information online. Internet activists have been harassed, detained and tortured. The Syrian regime has tightened its grip on internet usage by applying filtering and censoring technologies to closely monitor Internet content that could potentially destabilize the regime. Reporters Without Borders (2011) describe the Syrian regime as ‘enemy of the internet’.

Accordingly, Syrian authorities blocked access to the social networking service Facebook on Syria‘s internet servers on November 19, 2007 stating that the social media platform promoted attacks on authority (Wikipedia). Additionally the Syrian regime also feared that the Israeli government would gain access to Syrian social networks on Facebook. In March 2008 it blocked Maktoob.com, one of the largest email and blog portals in the Arab world, the impact of which stopped Syrians from having access to over 3,000 Arab blogs. Other social networking sites such as Wikipedia, Blogspot and YouTube are also blocked (ASMR, 2011) as was the Arabic Wikipedia from April 30, 2008 until February 12, 2009 (Wikipedia).

Ironically, in June 2011 in the middle of the uprisings, the Syrian the regime restored Facebook and YouTube. The shrewd regime aimed to track down activists, capturing them and stealing their usernames and passwords to spread propaganda, dismantle communication networks and to gain information about the social movements’ plans for pre-emptive strikes. This move by the regime supports Morozov’s (2011) theory of ‘The Net Delusion’, where he argues that information technologies are in the hands of authoritarian regimes not in the hands of activists. As Morozov (2011:xiii) put it ‘the internet may favour dictatorships rather than democracies’.

In order to crack down on social media activists during the 2011 uprisings, the tech-savvies working for the Syrian regime have applied many strategies to paralyze information diffusion, hunt down activists and destroy communication channels. These have included setting up a fake YouTube, Facebook interference, Skype encryption and information warfare.

The fake YouTube

YouTube has been cited as a vital platform in the Arab Spring uprisings particularly in Syria. It has aided revolutionaries in many ways. First, it highlighted the regime’s brutality by documenting events via mobile phone technology that has led to the expansion of the geographical proximity of the uprisings and by raising awareness among the Sunni sect. Second, it worked as the alternative press, an informative platform that diffuses information to most of the world news outlets. And finally it has captured what will become tangible evidence and witness to Assad’s crimes against his people. According to Alex Fitzpatrick ‘the world is watching the Syrian uprisings on YouTube’ (Fitzpatrick, 2012). The battered body of the 13 year old Hamzeh Al-Khateeb was the first video uploaded on YouTube showing the regime’s ruthlessness. Those trying to view the video found a message saying, ‘this video has been removed as a violation of YouTube’s policy on shocking and disgusting content’ (Melber, 2011).

YouTube has posed a major threat to the regime’s propaganda and stability. In revenge, the SEA has cloned YouTube website to trap Syrian digital activists. However, the fake YouTube page attacks users in two ways. First, it requires you to enter your YouTube login credentials in order to leave comments. Second, it installs malware disguised as an Adobe Flash Player update (EFF, 2012) so that the attacker can command and control a computer’s contents.

Facebook interface

Facebook is considered the second most important social media site that the revolutionaries rely on to expose the Syrian regime. The government had allowed Facebook to remain available for the purpose of trapping Syrian activists. Syrian activists have harnessed the power of Facebook pages in recruiting, coordinating and diffusing information to local and worldwide audiences. The most powerful Facebook pages have been ‘We are all Hamzeh Al-Khateeb’, the ‘Syrian revolution 2011’ and ‘Euphrates Revolution Network’ (ERN). Again the ‘we are all Hamzeh Al-Khateeb’ Facebook page was shut down by Facebook administration on 30 August 2012 but then restored on 2 September 2012, after a message was sent by the page administrators saying:

Dears Messrs

We demand that the respectful Facebook management return the page of the child martyr Hamza al-Khatib (more than 500,000 fans) that have been deleted today, despite of being a great reference in publishing what really happens in Syria for the public opinion, press and human rights organizations and humanitarian. We ask you in the name of the revolutionary Syrian youths against the criminal regime of Bashar al-Assad (‘We Are All Hamzeh al Khatib’ Facebook portal, 2012).

Facebook pages set up by dissenters and revolutionaries are directly targeted by the SEA and are reported for spam. The SEA has also established their own Facebook pages such as ‘the Syrian Electronic Army’ and many pro Bashar Al-Assad pages with few ‘likers’. The SEA with malware targeted the Facebook interface. The Facebook login page within Syria is “login1.cixx.com” and a similar link was visible on Facebook revolutionary pages with prompts asking users to post and share ‘good news’. However, using this link would cause huge damage. According to EFF (2011), this attack steals usernames and passwords and could potentially give an attacker access to all of the private information in your Facebook account.

Skype encryption tools

Skype has been an important revolutionary tool enabling live reporting to the world, especially to the Al Jazeera satellite channel. It has also been important in facilitating communication between the coordination revolutionary divisions. Because of this, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF, 2012) has reported that Skype has been directly targeted by the regime with a Trojan called ‘DarkComet (RAT)’. The Trojan allows an attacker to capture webcam activity, disable the notification setting for certain antivirus programs, record key strokes, steal passwords, and more – and it sends that sensitive information to the same Syrian IP address used in attacks (Galbren, et al, 2012).

Information warfare

SEA has launched ‘disinformation’ attacks in November 2012, targeting mainly the online platforms of Al Jazeera and Al-arabiya satellite channels. These attacks came as the two channels supported the revolutionaries and criticized the Assad regime’s handling of the crisis. The (SEA) managed to post a number of false stories on the Al Jazeera portal (http://www.aljazeera.net). These included examples such as ‘the Qatar’s Regent ousted his father and send him to exile’ and ‘A huge fire erupted in Qatar and over 22 people were killed’. By posting such news the SEA intends to destabilize the state of Qatar.

Furthermore, the regime has issued a ban on iPhones warning that anyone found in possession of one would be treated as a suspected spy. The ban is an attempt by the government to control information getting out of the country. In a statement, apparently issued by the Customs Department of the Syrian Finance Ministry and seen by Lebanese and German media, the authorities ‘warn anyone against using the iPhone in Syria (BBC, 2011). This ban is in response to fears of what the iPhone can offer revolutionaries: high quality photos and videos, and connection to wireless internet. It has been reported that the Al Jazeera documentary (‘Songs of Defiance’), was all captured on an iPhone as carrying a camera was considered a dangerous, life-threatening activity (Huffington Post, March 13, 2012).

Social media cyber-war

In his book Cyber-War (May 2010), U.S. government security expert Richard A. Clarke defines ‘cyber-warfare’ as ‘actions by a nation-state to penetrate another nation's computers or networks for the purposes of causing damage or disruption (cited in Wikipedia). In the Syrian case however, there are three levels of information cyber-war waged. The first is the State versus foreign organizations such as the Al-Jazeera satellite channel and Harvard University. The second is the State versus individual actors at both local and international levels in the sense that the nation has been divided into two. On March 15, 2011, the day the Syrian Sunnis demonstrated in Deraa demanding reforms and liberty, the ‘one nation one people’ concept vanished forever and what we see now is truly a sectarian war. Additionally, the army, which has been called Humat el Dyar, the protectors of the land, has also divided into two. Thereby, two peoples (Sunnis and Alawite) and two armies (the Syrian army and the free Syrian army) are now waging two different wars (physical and virtual). Finally, foreign organizations versus State so that ‘Hacktivist’ groups such as Anonymous and Telcomix have attacked and supplied information technologies to enable the revolutionaries to attack the Syrian government information resources. Thus a massive social media virtual war is being carried out between the SEA and SFA in order to win the media war.

The revolutionaries are thus using digital communication as vital tools to fight the repressive Syrian regime. In response, according to Assad’s comments on revolutionaries ‘winning the battle of the cyberspace’, the Syrian government tech-savvies have opened the ‘cyberspace front’ led by the Syrian Electronic Army (SEA). SEA spokespeople have denied any connection to the Assad regime and SEA ‘soldiers’ are presented as patriotic Syrian hackers who have vowed to defend the regime. However the Citizen Lab of Toronto University (Canada) has traced the (SEA) ISP and confirmed that it belongs to the Syrian ‘Mukhabarat’. Their mission was stated clearly by Qasim Raya:

As in sky, sea and land … Syria has another type of army roaming in the virtual world and cyberspace, tracing and targeting everyone trying to hurt our nation and its people (Raya, 2012).

Social media networks have played a vital role in the protest movements that have rocked the country for the past 18 months. The revolutionaries’ coordination groups have set up Facebook pages, Twitter accounts and YouTube channels so that they can communicate, coordinate and disseminate news and videos. The most powerful pages are those belonging to ‘The Syrian revolution 2011’ Facebook page with over 504,000 likers, and @revolutionsyria on Twitter with around 49,500 followers. Additionally, the Syrian Free Army has created its own Facebook page and Twitter account for recruiting, propaganda, and diffusing news about the armed struggle minute-by-minute. On June 20, President Assad praised the SEA calling them ‘the real army of the virtual reality’ (Assad, 2011). As the battle on ground escalated however, the online frontier became heated. The SEA launched an aggressive attack on the SFA Facebook pages, posting pro-Assad comments and reporting it for spam to Facebook administration.

The SEA initially succeeded in shutting down ‘The Syrian revolution 2011’ Facebook page, but it was later restored after contacts with Facebook administration. #Syria has been targeted by ‘TH3 Pro’ the SEA special operations department who post pro-Assad tweets, but again the Twitter administration intervened and removed all comments posted by ‘TH3 Pro’. In retaliation, the SEA Facebook page was reported for spam by the SFA. In a plea posted by the SEA asking for support to evade shut down by Facebook administration, the SEA urged sympathisers to join and post supportive comments – yået it has been shut off. The SEA managed to get the page back under a different name called ‘åal-Nidal Al-Sory’ (struggle for Syria), but again this page with almost 22,000 likers has been targeted by SFA and shut down.

I have monitored the attempts of the SEA to set up new Facebook pages. The SEA moved their ‘Facebook Hacktivism’ in a different trajectory by opening the fire on some of the world’s most prominent figures who have been publicly supporting the freedom fighters. The SEA has since launched coordinated attacks on Facebook and Twitter directed at the Facebook pages of US President Barack Obama, US television entertainer Oprah Winfrey, former French President Nicolas Sarkozy and others. Comments by Mais Latif such as ‘leave us alone, we love Bashar’, and another comment by Kamal Ibraheem, ‘please stay away from us … we love Syria’, are typical of the many hundreds of comments directed to Obama, Winfrey, Sarkozy, and others. Nonetheless, in revenge, the revolutionaries’ tech-savvy has managed to close down all ‘SEA’ Facebook groups, and despite many attempts to retrieve the pages, Facebook administration has blocked them all. Additionally, the SFA has managed to hack the Syrian parliament and other TV station websites such as ‘Al Donya’ using (DDoS) distribution denial of service software. However, there is no trace of SEA Facebook activity between April to August 2012 as they lost the Facebook battle. In early September 2012 the SEA resumed their Facebook activism under the name ’The Pro-Battalion’.

Cyber attacks

The Syrian Electronic Army, an arm of the embattled regime's intelligence service, is engaging in cyber-warfare. According to a report by Reuters (Reuters, 2011),

‘Cyber-attacks are the new reality of modern warfare,’ said Hayat Alvi, lecturer in Middle Eastern studies at the US Naval War College. ‘We can expect more ... from all directions. In war, the greatest casualty is the truth. Each side will try to manipulate information to make their own side look like it is gaining while the other is losing’ (cited in Goldman 2012).

In February 2012, CNN reported: ‘Computer spyware is the newest weapon in the Syrian conflict’. According to the Citizen Lab of Toronto University (2012), the majority of these attacks have involved the use of the Dark Comet RAT. Remote Administration Tools (RAT) provide the ability to remotely survey the electronic activities of a victim by key- logging, remote desktop viewing, webcam spying, audio-eavesdropping, data exfiltration, and more.

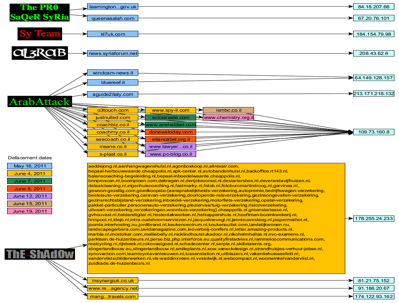

Thus, the SEA have turned their online ‘Hacktivism’ to launch cyber attacks against satellite channels such as Al Jazeera and Al-arabiya. The Al-Arabiya Twitter account was attacked, with a statement on Twitter by @Alarabiya announcing that ‘we would like to inform you that our social media site was hacked’. The SEA hackers have also successfully hacked British government websites, Harvard University and several international organizations (see Figure 1). They left a message on the hacked webpages in both Arabic and English languages saying ‘sorry we don’t want to destroy your official website, but the British government actions against Syria … STOP to interfere in Syrian affairs … leave us alone’ signed by the PRO SaQeR SyRia@gmail.com.

The Al Jazeera satellite channel’s webpage disappeared on September 5, 2012, and a statement was left on the webpage interface signed by Al-Rashedoon (the matures) saying that ‘in a response to your position against our country, supporting the armed terrorist groups and dissemination of false news and fabrications your website is being hacked, and this is our answer to you.’ Al Jazeera online services were restored on September 7, but two days later the Pro-Battalion claimed that they had hacked Al Jazeera mobile services and disseminated fabricated news. Al Jazeera mobile service has played a key role in information dissemination by the Syrian activists by sending direct messages to (sharek.aljazeera.net). According to ABC News, ‘Al-Jazeera says hackers have targeted the Qatar based TV satellite channel for the second time in a week, sending out false news reports on its mobile phone alert service’ (ABC News, 2012).

Moreover, the SEA have recently issued denied service attacks (DDoS) against the national Syrian council website that represent the Syrian opposition, and on the Arab League for offering the Syrian seat to the revolutionary council during the 24th Arab summit in Doha on March 26, 2013.

Figure 1 (above) shows the SEA hacking divisions and the direct attacks on foreign websites.

Israeli IP addresses were also directly targeted by ‘the Arabattack’ hackers division, which is politically significant and is used as a propaganda tactic to highlight the Arab-Israel conflict. The SEA and its support groups direct sympathisers to various related resources including websites that have already been compromised and encourages them to practice their hacking skills on the compromised websites.

In retaliation, the SFA with the help of the local coordination committees, Anonymous groups and Telemoix, have established counter-cyber warfare. They managed to hack the Syrian parliament and Syrian national TV web sites. On the Facebook frontier, the SEA Facebook group disappeared after it was reported to Facebook administration, and the Pro-Battalion group lost their page on July 17, 2012, but it was back again on September 6, 2012. Furthermore, in a strike, the Syrian activists in June 2012 managed to hack the Syrian President’s private email address in what has become known as ‘Email-Leaks’. The Guardian Weekly newspaper and Al-arabieya Satellite Channels exclusively have obtained over 5,000 leaked emails. On September 5, 2012 the operation hacking the president’s e-mail was unveiled. In an interview with the Al-Hayat daily newspaper, the Syrian activist Abdullah Al- Shamary revealed how he and his tech-savvy activists had accessed President Bashar’s private E-mail address. Al-Shamary had sent an email to Bashar’s top ministers pleading with them to stop the bloodshed in the name of the nation and asking them to show his email to the President; one of the ministers replied back with a link to Bashar’s private email address. Al-Shamary decided to break the password, an operation that took months without any results until one of his friends suggested ‘let’s be stupid’ and they tried the password ‘1234.’ It worked. The email leaks have also helped the revolutionaries by providing sensitive information about military operations.

Information warfare perspective

The Syrian revolution is totally different from other Arab Spring revolutions. On the one hand all means of information communication tools have been harnessed by the revolutionaries in their attempts to bring about the downfall the regime and on the other the Syrian regime has also used social media platforms and applied surveillance technologies to fight back. Thus, we are witnessing a transformation from traditional media to internet media which is accessible by all parties. As Manuel Castells (2011) has pointed out, power is fundamentally concentrated in the communication information technologies. Yet the revolutionaries are winning the media war by highlighting the regime’s brutality, raising awareness, disseminating information, recruiting, and fundraising. In this respect Niekerk (2011) has stated:

The offensive ‘weapons’ can be considered to be the online social media and the Internet, the international mass media, and the mass human protests themselves. As many of the protest signs were in English, it may be assumed that the message was not only being directed at the national government but also at the international community to try to gain support and sympathy (Niekerk et al, 2011).

To put the Syrian revolution in the context of ideas about information warfare, Martin Libicki in his book What is Information Warfare (1995), has distinguished information warfare by:

command-and-control warfare (which strikes against the enemy's head and neck), [if] intelligence-based warfare (which consists of the design, protection, and denial of systems that seek sufficient knowledge to dominate the battle- space), electronic warfare (radio-electronic or cryptographic techniques), psychological warfare (in which information is used to change the minds of friends, neutrals, and foes), ‘hacker’ warfare (in which computer systems are attacked), economic information warfare (blocking information or channelling it to pursue economic dominance), and cyber-warfare (a grab bag of futuristic scenarios) (Libicki, 1995:12).

Furthermore, Reto E. Haeni (1997:4) has defined information warfare as:

[a]ctions taken to achieve information superiority by affecting adversary information, information-based processes, information systems, and computer-based network, while defending one's own information, information-based processes, information systems, and computer-based networks.

For Brett van Niekerk (2011), the philosophy of information warfare is that information and related technologies are an offensive weapon as well as a target.

In the context of the information warfare perspective, the plethora of cyber-attacks by both sides has changed the dynamic of the combat at a large scale that has transformed social media platforms from social to political in order to achieve political gain. According to Chatterji (2008), ‘psychological operations may be used to achieve military or political goals. Network-centric warfare is the integration of individual elements or platforms to create a single cohesive fighting force through networking that can maximize the effective combat power’ (cited in Niekerk, 2011).

In this sense, the cyber-attacks and disinformation has transformed social media platforms into a battle space. As Haeni (1997: 3) put it: ‘In the information age, warfare changes to information war’. For example, the Syrian regime with the help of SEA has fabricated most of what has been broadcast on state-owned media outlets. They present the revolutionaries as ‘terrorist armed groups’ who are terrorizing the people and looting military equipment to kill the Syrian people. On the other hand, the counter-power of the SFA has used the power of information to wage psychological war, showing for example, the captured intelligence top leaders and the anti-aircraft missiles (SAM) on YouTube videos. Such images have shattered the regime’s ‘invincibility’ and eased the air strikes on civilians.

Conclusion

As the outcome Syrian revolution is yet to be determined, the Syrian revolutionaries are fighting unequal war on both the ground and in cyberspace. Nevertheless, the online battles have great impact on the ground battles as the revolutionaries’ propaganda is powerful and has raised the moral of their on-ground fighters and gained international sympathy and support.

No doubt, social media platforms and information communication technologies ICTs have empowered the Syrian revolutionaries by supplying the tools with which to steer the world to their own media. However, in many of the online conflicts, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter administrators have worked for the interest of the revolutionaries.

Accordingly, the SEA has blamed Facebook Administration for closing down nearly 200 of its pages, Twitter has deleted many pro-Assad comments on #Syria, and YouTube has turned a blind eye to videos posted by the revolutionaries that violate the ‘community guidelines’, all of which has hindered the efforts of the regime to convince the world that what is going in Syria is a conspiracy led by the United States and Israel. Thus, the question of the social media networks neutrality during the Syrian revolution in aiding the revolutionaries at the expense of the regime is questionable and worthy of study.

References

Al-arabiya (2012). The hacking of the president Bashar email. Retrieved from: http://www.alarabiya.net/articles/2012/09/05/236158.html Or: http://alhayat.com/Details/432124.

Al-Assad, B. (2011, June 21). Speech of H.E. President Bashar al-Assad at Damascus University on the situation in Syria. Damascus, Syria. Retrieved from: http://www.sana.sy eng/337/2011/06/21/353686.htm.

Al Jazeera documentary (2012). Retrieved from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/13/al-jazeera-syria-documentary-iphone_n_1342395.html.

Al Jazeera (2011). Hackers sent a false mobile message. http://abcnews.go.com/International/al-jazeera-hackers-false-mobile-texts/comments?type=story&id=17194986#.UVYmAxzX_zw.

Arab Social Media Report (2011). Retrieved from: http://interactiveme.com/index.php/2011/06/twitter-usage-in -the-mena-middle-east/

Arab Social Media Report (2011). Social Media in the Arab World: Influencing Societal and Cultural Change? Dubai School of Government.

BBC (2011). The Syrian Revolution (documentary). Retrieved from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5BhaF6MjRo

BBC (2011). Syria 'bans iPhones' over protest footage. Retrieved from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-16009975, 2nd December 2011.

BBC (2011). Inside the Secret Revolution in Daraa (documentary). Retrieved from: YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zBU0wwzd-fw.

Castells, M. (2011). A network theory of power. International Journal of Communication, Issue 5. Retrieved from: http://ijoc.org/ojs/index.php/ijoc/article/viewfile/1136/553

Citizen Lab (2012). University of Toronto report Retrieved from: http://citizenlab.org/page/3/?s=syria CNN (2012). Syrian Cyberwar. Retrieved from: http://newsstream.blogs.cnn.com/2012/02/09/syrias-cyberwar.

Electronic Frontier Foundation (2012). Report. Retrieved from:http://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2012/03/fake-youtube-site-targets-syrian-activists-malware.

Fitzpatrick, A. (2012). The world watching the Syrian uprisings on YouTube. Retrieved from: http://mashable.com/2012/02/07/syria-youtube.

Galberin, E. & Boire, M. (2012). Campaign Targeting Syrian Activists Escalates with New Surveillance Malware. Retrieved from: http://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2012/04/campaign-targeting-syrian-activists-escalates-with-new-surveillance-malware.

Haeni E. Reto (1997). Information warfare: An introduction The George Washington University, Cyberspace Policy Institute Washington DC, can be retrieved from http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/infowar.pdf.

Huffington Post (2013, March, 3). Al Jazeera To Air Syria Documentary Filmed On iPhone. Retrieved from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/13/al-jazeera-syria-documentary-iphone_n_1342395.html

Information Warfare Monitor (2011, June 25). Syrian Electronic Army: Disruptive Attacks and Hyped Targets. http://www.infowar-monitor.net/2011/06/syrian-electronic-army-disruptive-attacks-and-hyped-targets/

Karam, Z. (2011, September 27). Syria wages cyber warfare as websites hacked Associated Press. Retrieved from: http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5h_ALtePegit5Y7joOwz51xnk-dSA?docId=86d93bf5fa04fe7a132c428ca97bb92.

Goldman, L. (2012) In Syria's Civil War, Cyber Attacks are the ‘New Modern Warfare’. Retrieved from: http://techpresident.com/news/22700/syrias-civil-war-cyber-attacks-are-new-modern-warfare

Khamis, S., Vaughn, K. & Gold, P. (2012). Beyond Egypt’s ‘Facebook Revolution’ and Syria’s ‘YouTube Uprising’: Comparing Political Contexts, Actors and Communication Strategies. Arab Media & Society Issue 15, Spring 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.arabmediasociety.com/?article=791

Faris, D. (2008). Revolutions without Revolutionaries? Network Theory, Facebook, and the Egyptian Blogosphere Arab Media and Society Issue 6, Fall 2008. Retrieved from http://www.arabmediasociety.com/?article=694

Libicki, M. (1995). What is information warfare: National defence University of Washington DC for National Strategic Studies , the Centre of Advanced Technology. Retrieved from: http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA367662

Melber, A. (2011, May 31). YouTube reinstates blocked video of child allegedly tortured in Syria. The Nation. Retrieved from http://www.thenation.com/blog/161050/youtubereinstates-blocked-video-child-allegedly-tortured-Syria

Morozov, E. (2011). The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom New York: Public Affairs.

Niekerk B., Van Pillay K. and Maharaj M. (2011). Analysing the role of ICTs in the Tunisian and Egyptian Unrest: From an information warfare perspective International Journal of Communication 5, 1406–1416.

Taki, M. (2010). Internet censorship in Syria – Bloggers and the Blogosphere in Lebanon & Syria Meanings and Activities: University of Westminster for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

Reporters Without Boarders (2012). Enemies of the internet Retrieved from: http://en.rsf.org/IMG/pdf/rapport-internet2012_ang.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyberwarfare

Raya, Q. (2012).The Syrian electronic army in the scale of cyber wars.(translated from Arabic text). Retrieved from http://alkhabarpress.com

The Syrian revolution (2011). Facebook page. Retrieved from: http://www.facebook.com/Syrian.Revolution.

We Are All Hamzeh al-Khateeb Facebook group (2011). Retrieved from: http://www.facebook.com/hamza.alshaheeed.

Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information warfare.

About the author

Ahmad Shehabat is a Jordanian with over five years experience working in media with international satellite channels such as Al Jazeera, ABCNEWS and APTV. He has an MA (Hons) and an MA in Communications and Cultural Studies from the University of Western Sydney (UWS). He is also a research candidate in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts at UWS. His thesis title is ‘Arab 2.0 revolutions: Investigating social media networks in political uprisings in the Arab world’