McKenzie, Nick - Crossing the Line: The Inside Story of Murder, Lies and a Fallen Hero, Gadigal Country: Hachette Australia, 2023, (pp. 461). ISBN: 9780733650437

Reviewed by Bridget Brooklyn - Western Sydney University

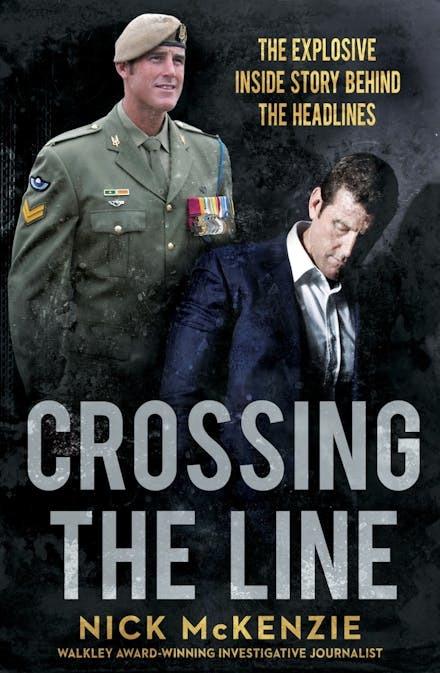

Given the extensive media exposure of the sensational defamation suit brought by former Special Air Service (SAS) soldier Ben Roberts-Smith against journalists Chris Masters and Nick McKenzie, how much more could the ‘inside story’ reveal? This is an especially pertinent question as the case followed the well-publicised Brereton Inquiry’s 1 findings of a culture of violence in the Australian Defence Force’s SAS that transgressed the rules of war. Yet both journalists have published their own account of the case, suggesting that yes, there is much more to reveal. In such accounts, we are bound to travel over much familiar ground, so a successful ‘inside story’ must be literally that – to take us inside the case to areas we haven’t seen. In this one, there was plenty that I had seen, but McKenzie’s book also offers some view of what it was like to be ‘inside’ journalist Nick McKenzie during the six years between when his first exposé of Roberts-Smith – then unnamed but easily identified – appeared in Fairfax papers, and the eventual dismissal of Roberts-Smith’s defamation suit against the two journalists in 2023.

Apart from laying out the story from beginning to end, including many aspects of it that we did not hear on the news, McKenzie gives us some insight into the dangers of investigative journalism. The fear of making big, public mistakes, of being sued for defamation and of threats by powerful actors with a lot at stake had frequently seen the author ‘double over the toilet in the morning, dry retching from stress’ (106), so that, 15 years into a very successful career, he was ready to leave it. These were all occupational hazards I had never given much thought to. But the lure of this particular story seems to have been sufficient for McKenzie to rediscover his mojo, leaving him ‘feeling more alive than I’d felt in months’ (108).

The book is also revealing of the culture of the SAS beyond the very ugly rumours outlined in a report that seems to have appeared unintentionally, at least initially, when it was commissioned in the wake of the 2014 Lindt Café siege 2 , with the aim of looking into the viability of greater military involvement in response to domestic terror threats. The report’s author, Samantha Crompvoets, turned over a rock that had been hiding some particularly nasty things, prompting first Masters, then McKenzie, to pursue the story. The culture that Crompvoets identified was nevertheless not the only cultural conflict in the SAS, and the exposition of the countervailing moral forces in the regiment – between its reputation as a violent free-for-all and a culture grounded in abiding by the Geneva Conventions – creates much of the tension in McKenzie’s book. That came as a surprise to this Baby Boomer raised on sentiments such as ‘war is not healthy for children and other living things’. Wasn’t the SAS just an assembly of cold-blooded killers?

The relationship between those trained to be able to kill without pity and the ethics of war is an uncomfortable one, and it seemed to me before reading this book that one of the characteristics of warfare is that it would be difficult to find a clear demarcation between the two. However, the book’s title declares the opposite – that the line is clear, and that those who cross it do so knowingly and in breach of what they have learned about the honour of being a soldier. Again, it was a surprise to find the book peppered with stories of this other, more noble, culture. For evidence that it exists we need look no further than the fact that stories of unlawful killings began to surface in the first place.

The Anzac legend, of course, lurks behind this mission. While McKenzie does not invoke it sentimentally, he reminds us that much modern Australian culture, both military and civilian, is informed by this pervading tale. The theme of the essential nobility of the Australian soldier, true to his Anzac roots, begins in the book with the story of one seasoned SAS sergeant, Boyd Keary (not his real name), who had joined the army after reading an Anzac Day story about an Australian at Tobruk who had saved the life of a wounded German soldier. Early on in his deployment to Afghanistan, Keary had been able to do the same for a wounded Taliban fighter (52). There is, then, an ideal to live up to, and a strong sense of something very rotten in its breach. As an historian, I am aware that, from 1915, there have always been breaches of that ideal, even as it was forged (to apply the somewhat grandiose verb generally appended to that bringing together of Aussies and Kiwis in a failed invasion of Turkey). For soldiers such as Sargeant Keary, that honourable tradition had been perverted by a core of men who did fit the description of cold-blooded killers. As McKenzie reports, Roberts-Smith emerged at the centre of that cohort very early into the investigation of SAS conduct in Afghanistan. At the author’s first meeting with renowned investigative journalist Chris Masters 3 about the Crompvoets report, Masters mentioned ‘a soldier I had heard of but knew little about. As Masters talked, I googled the man’s name: Ben Roberts-Smith’ (105).

As an experienced journalist and author, McKenzie knows how to take a series of complicated events and structure a narrative that the general reader will be able to follow — if not always in every aspect, at least sufficiently to keep the thread going without having to constantly rifle back through pages thinking ‘Who is this guy again?’ The need to structure the narrative carefully, but also to make an absorbing story, often results in a ‘cliffhanger’ style of short chapters. In a neat, three-part structure, McKenzie unfolds his complicated story, setting the scene with the events in Afghanistan that prompted the rumours, then allegations, of war crimes. Then, from Samantha Crompvoets’ initial brief to explore the possibility of greater Defence engagement in combating domestic terrorism, through the stories that emerged during her exploration, McKenzie brings us to the involvement of the two journalists, Masters and himself. With detailed accounts of his research, and the lawsuit that followed the journalists’ revelations, McKenzie unfolds the story largely in chronological order – with the disclaimer that, for clarity, the order is not always strictly chronological. He helps the reader track this chronology with dates that form the subtitle of each chapter, although some chapters, containing several concurrent events, can have at times have a fervid, jump-cut quality.

Although most people drawn to this book probably know how the story ends, McKenzie’s narrative style gives flesh to the bones of the media reports, as well as giving his part in the drama a life beyond the news cycle. It is also clear that McKenzie wants us to know some important things about soldiering, and about journalism – that the goals are praiseworthy, that there are good and bad ways to go about both professions, that a code of ethics governs both, and by which most of the members of each of profession abide.

McKenzie reminds us repeatedly that journalism is about telling the truth. He sets out in the Author’s Note at the beginning of the book that the story is told from his perspective, but also from the perspective of those involved, from the SAS testimony alleging war crimes to the man at the centre of them (ix). Given that this ‘inside’ story goes inside McKenzie’s investigative process – not anybody else’s — the story rarely reads as being told from any perspective other that of Nick McKenzie. That is no bad thing, and perhaps he could have owned that perspective more wholeheartedly.

If journalism at its best is something fine, then so is soldiering at its best – and another of McKenzie’s goals is to set out how men of principle, such as Liberal politician and ex-SAS soldier Andrew Hastie, reconcile a task that involves ruthless killing where necessary with a strong moral code. Here, McKenzie takes a shortcut in portraying Hastie as one on the side of the angels, by referencing his speech in Parliament in May 2018, mentioning allegations of bribery against billionaire Chau Chak Wing, which followed Dr Chau’s successful defamation suit against McKenzie and others for an ABC report on his financial dealings. Briefly mentioning the suit, McKenzie’s portrayal of Hastie’s allegations under parliamentary privilege is part of his larger portrait of Hastie as a highly principled former SAS soldier. Well and good, but the link is tenuous and confusing. In contrast to McKenzie’s interpretation, other media coverage of this speech suggests that, regardless of the truth or otherwise of the claims against Dr Chau, Hastie’s speech could be interpreted in several ways — some favourable, some not — and McKenzie’s use of it adds a dimension that could be taken by a casual reader unfamiliar with the Chau defamation suit to be about the SAS.

Despite missteps like this, McKenzie’s message strongly asserts that while both soldiering and journalism can be ruthless and even compromised under some circumstances, the belief in what is right governs most practitioners of either profession. This claim doesn’t shy away from the reality that for the SAS, as for the Anzacs, ‘serving’ one’s country also means ‘killing’ for it. But killing for your country is not indiscriminate, as Keary, the sergeant inspired by the Anzac at Tobruk, demonstrates:

The job of the SAS was to capture or kill, provided it was done within the rules of engagement. Hundreds of Taliban insurgents had ended up on formal capture or kill lists, and many of them had rightly been taken out. Keary was no squib when it came to killing by the book (52-53).

Abiding by the Geneva Conventions was not just the right thing to do, though. The rationale for acting ‘by the book’ also related to soldiers’ well-being: soldiers must live with themselves when they leave the war zone. Another member of the SAS, Nick Simkin (also not his real name), had warned Hastie before deploying to Afghanistan not to do as others, notably Roberts-Smith, were doing: ‘Hastie could still remember Simkin’s exact words: “People are doing stupid shit overseas. Don’t be that guy. Don’t ruin your life”’ (66).

If Simkin’s words were blunt, those of a junior SAS officer who spoke off the record were more blunt: ‘They are selecting fuckwits … Attack dogs … light switches that can’t turn off’ (140), adding the example of a patrol commander who had deployed despite a domestic violence charge against him and the fact that he carried a home-made hatchet with him in Afghanistan. This vignette of a Colonel Kurtz-like figure suggests that the rottenness in the SAS will take some time to excise. While McKenzie’s admiration of those who helped expose Roberts-Smith can get a little misty-eyed, he reminds us that there are still those who only testified because they were subpoenaed and were hostile to the proceedings. One witness testifying to the unlawful execution of a Taliban member used his time in the stand to say that Roberts-Smith ‘was under an extreme amount of distress for killing bad dudes who we were sent over to kill’ (398).

McKenzie is aware that journalism, like soldiering, can be viewed with a jaundiced eye by those who denounce ‘the media’ (as if it were a monolith) for crimes against veracity. McKenzie’s belief in journalism’s essential nobility is nowhere more amply demonstrated than in his account of the support of James Chessell, his boss at The Age newspaper (now part of the Nine Entertainment group), who at considerable risk to his career, permitted McKenzie to name Roberts-Smith. McKenzie reminds us that good journalists are everywhere, whether they work for the ‘tabloid’ programs or the more ‘serious’ papers and channels. (210-11). The fact that Chessell’s career remained intact also strengthens McKenzie’s view that we can underestimate the place that even large corporations will make for investigative journalism.

As a practitioner of this essential branch of the profession, Nick McKenzie is highly regarded, and the book delivers a coherent and absorbing account of this shocking story, as well as some perceptive observations of the theatrical process of court hearings. As a good journalist, he is a good storyteller, albeit in a journalistic style that can grate after 450 pages. The prose can tend towards the purple, such as Hastie’s ‘dreams laced with dread’ (65). People he admires have a ‘fierce intellect’ or are ‘ferociously smart’ (71), and references to Roberts-Smith are cumbersomely synonymous — ‘the VC recipient’, ‘the ex-soldier’. Simply repeating his name or using a pronoun would be less tiresome. Equally tiresome is the common journalist error of using ‘prevaricate’ when they mean ‘procrastinate’.

In light of the enormity of the crimes that resulted in the success of McKenzie’s and Masters’ truth defence to Roberts-Smith’s defamation, such nitpicking seems petty. Perhaps less petty is a sense that at times McKenzie himself stretched the narrative in a way that could reduce the story to moral certainties to keep that narrative flowing. Despite my reservations, this is a story that, after all the media coverage that made it so familiar, is one worth telling and worth reading.

Footnotes

[1] The Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force Afghanistan Inquiry Report, commonly known as the Brereton Report (after the investigation head), is a report into war crimes committed by the Australian Defence Force (ADF) during the War in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2016. The investigation was led by Paul Brereton, who is both a New South Wales Supreme Court judge and a major general in the army reserve. The independent commission delivered its final report on 6 November 2020. The redacted version was released publicly on 19 November 2020.

[2] The Lindt Café siege was a terrorist attack that occurred on 15-16 December 2014 when a lone gunman, Man Haron Monis, held ten customers and eight employees of a Lindt Chocolate Café hostage in Martin Place, Sydney. The siege led to a 16-hour standoff, after which police officers stormed the café. Hostage Tori Johnson was killed by Monis and hostage Katrina Dawson was killed by a police bullet ricochet in the subsequent raid. Monis was also killed.

[3] Chris Masters is a renowned Gold Walkley award winning writer and ABC investigative journalist, with multiple credits for high profile investigations for the ABC’s flagship program Four Corners including “French Connections” (1985) about the sinking of the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland harbour and the “The Moonlight State” (1987) report that led to the Fitzgerald Inquiry into political corruption in Queensland. Masters has written earlier books on Australia’s military past including Uncommon Soldier: Brave, Compassionate and Tough, the Making of Australia’s Modern Diggers (2013), No Front Line: Australia’s Special Forces at War in Afghanistan (2017) and Flawed Hero: Truth, lies and war crimes (2023) on the SAS and Ben Roberts-Smith.

About the reviewer

Dr Bridget Brooklyn, is a Lecturer in History and Philosophical Inquiry in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University. Her research interests are late 19th and 20th century Australian social and political history, particularly feminist political history. She is currently researching conservative feminist activity in early 20th-century Australia. Recent publications include ‘Review essay on global and world histories of feminism and gender struggle’ in Lilith: A Feminist History Journal (2023) (with A. Downham Moore), and Australia on the World Stage: History, Politics and International Relations, (2023) (ed with B. Jones & B. Strating).