Gilmore, Jane - Fixed it: Violence and the representation of women in the media, Viking, 2019, (pp. 288). ISBN 9780143795506

Reviewed by Jane Scerri - Western Sydney University

For every 100 rapes that occur in Australia, eighty-eight will be committed by someone known to the victim, forty-five will be committed by the victim’s intimate partner, five will be reported to the police, two will go to court, one rapist will be found guilty and 0.5 rapists will go to prison (p. 86).

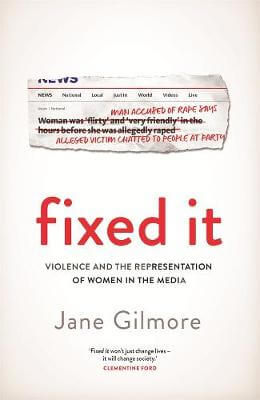

Jane Gilmore’s Fixed It examines how language can be used to erase crimes and blame victims. From the outset her voice is direct, impassioned, often funny, and at times, cautionary, but it never falters. She takes no prisoners in laying the blame for murder, rape and violence firmly where it lies – with the perpetrator. However, as she states, one of the most consistent issues the Fixed It project has identified is the media’s failure to depict perpetrators of violence, rendering them invisible (75).

The title Fixed It describes Gilmore’s simple, yet succinct process of striking out deliberate misrepresentation – literally with red pen. Her modus operandi is to decode the gendered language that is pervasive in Australian media and society. It is ironic that it is the male-dominated world of media – the one that so prides itself on objectivity and ‘cold facts’ – that persists in misrepresenting and obfuscating male violence against women. Each of Gilmore’s chapters highlights the myths that support and perpetuate inequality, inaccuracy of reporting, and most importantly the continuing violence against and oppression of women.

The book opens with a comparison of how the media treated the deaths of ABC staffer Jill Meagher and sex-worker Tracy Connelly. Using the good/bad woman analogy referred to by many feminists (famously explored in Summers’ classic Damned Whores and God’s Police, 1975), Gilmore explicates how gender, class and stereotyping serve to blame the victim. Gilmore hadn’t started writing Fix It when Connelly was murdered, but this was when she:

… started seeing it (my emphasis) everywhere. Not just in crime reports but also in political reporting, sports reporting, even articles about musicians and artists. Women are not people in the eyes of the news, at least not in the way men are. Women are tits and arse, they’re glamorous or fat, they’re wives or mothers or stupid or demanding or nagging or annoying or sweet or pretty. Men on the other hand are fully-rounded, complex people – as long as they’re not too woman-like (5).

Throughout the book, Gilmore illustrates how gendered language is used to reinforce male dominance by perpetuating myths and unconscious biases about masculinity and femininity. She also explores how these same biases keep men in the top jobs, and excuse their bad behaviour, expressly because of their maleness. In contrast, she shows how women are judged, blamed and not excused for their femaleness. And how – and she uses examples of women across class and status – if they aspire to agency, success or equality, none of which fit the feminine, good woman stereotype, they are deemed to exist in a liminal, no-man’s land limbo:

An easy way to prove a woman is unfit for public office is to measure her against the traditional expectations of womanhood. If she can be portrayed as pretty, feminine, compliant, sweet or nurturing she is a failure as a leader. If she is strong, ambitious, resolute and powerful, she is a failure as a woman. Either way she fails (203).

This model has been used to frustrate and stymie women historically, as attested to by feminists internationally. Gilmore states however, that of course it is not ‘all doom and gloom’, but we must remain vigilant. As Jill Julius Matthews reflecting on the history of feminism in the 1980s attested:

Every change in the patterns of the gender order brought new opportunities for women, and closed off others. Across the century, the feminine dance is curiously constant: one step forward, one step sideways, one step back. (1984, p. 199)

Put simply, and Gilmore does so succinctly: a good woman enjoys the benefits of femininity but not success, whereas a successful woman, is not a proper woman, so therefore open to all the diatribe associated with gendered vilification. She uses Hilary Clinton 1 and Julia Gillard as examples of the ridicule in store for women attempting to step up, quoting a leading on-line news article, that discusses the size of Gillard’s ear lobes, ‘“HECK, there must be a surgeon who can help!’, worried one voter yesterday in a web debate over Julia Gillard’s pendulous earlobes’ (208). As Gilmore comments, ‘Only in a bizarre parallel universe could anyone imagine the shape of a male prime minister’s ears becoming front page news or a credible reason to question his ability’ (208).

Throughout the book’s well-organised, lucid and amusing – despite the subject matter – 260 pages, using journalism and the media as a framework, Gilmore also explores how gendered language is also pervasive in sport, politics and pop culture, and most interestingly, she explains how myths about gender stereotypes diminish perpetrator blame by transferring it onto the victim. In the case of women victims, this blame is largely attributed to women who do not conform to the ‘good girl’ model/myth. In the case of child victims, she highlights that although they are not blamed for being raped or ‘assaulted’, they are de-humanised and objectified. As she clearly states four-year-old boys do not ‘have’ sex, they are raped, or sexually assaulted. This is how the ‘fix its’ are presented:

ABC: CHILD ABUSE LINKED TO ARTS SCHOOL INCLUDED FORCING 4YO BOY TO HAVE SEX, POLICE ALLEGE

FIX: CHILD ABUSE LINKED TO ARTS SCHOOL INCLUDED RAPE OF 4YO BOY, POLICE ALLEGE (13).

Fixed It is a meaty, compelling and easy read. And like all simple things that work well, we are left wondering, why nobody has thought of it before. Of ‘fixing it’ before. What is so gratifying about Fixed It is that Gilmore does not simply describe the problems, of which we feminist men and women are all too aware, but that she locates their sources (a wide range of media, mainly Australian, but some international), giving numerous examples of how gendered language is used to distort meaning and support a dominant patriarchal ideology. Her chapters on representation, highlight the importance of women’s visibility, flagging that the ‘girls up front’ tokenistic version of inclusion is not acceptable.

Gilmore debunks terms like ‘real rapes’ which implies that many rapes aren’t real, (as if the victim were imagining it), clearly identifying the difference between rape and sex. The chapter titled ‘Victims Perpetrators and the people who support them’ is fascinating reading, particularly when Gilmore explains the psychological ‘types’ of rapists, distinguishing between ‘admitters’ and ‘deniers’. Put briefly, the deniers blame the victim and the admitters blame the circumstances – anything but themselves.

Gilmore even draws attention to how perceptions of alcohol use are gendered and proposes a scenario in which two men go out drinking and one of them is raped – a case in which it would be ‘highly unlikely that anyone in the community, media or the justice system would imply the victim brought it on himself by having too many pints in the company of another man’ (88).

In the chapter ‘Injustice in the justice system’, we are reminded how prescient the constant threat of male violence can be, especially, when a woman charges a man – often a partner – with assault. Gilmore outlines the sheer terror one woman endured in her attempts to escape a man who almost killed her. In her desperation to keep her whereabouts secret she made a dossier of her assault records, printed it out and gave it to everyone she knew. On the flip side, she discusses the men who claim that domestic violence against men is not given enough attention. While Gilmore acknowledges their claim, she also puts in into proportion:

Maybe it’s true that in very few cases where women kill their partners, they are indeed cold-blooded killers. However, this doesn’t stand up to the in-depth view by the N.S.W. Coroner’s Court Death Review Team, which found that between 2000 and 2014, there was not one single case of a woman killing her partner without a significant case of her having been the victim of his abuse (191).

And, citing a study into judges conducted in N.S.W between 2002 and 2010 comparing sentences where women killed their male partners and men killed their women partners, women were given an average sentence of five years longer, and there were significant differences in the sentence remarks:

Positive comments on men, both murderers and victims, were common: they were described as being ‘a good provider’, ‘a hardworking member of the community’, ‘popular in [the] workplace’, ‘an honest, hardworking family man’ and ‘well respected…’ There were no negative evaluations of the men that killed women but the women who killed men were repeatedly described as ‘wicked’ ‘heartless’ ‘callous’ and ‘extremely manipulative’ (190).

One of the most enlightening aspects of the book is Gilmore’s depiction of how society, relying on entrenched misogynist myths and lame euphemisms such as ‘boys will be boys’ continues to excuse adult men for rape, domestic violence and murder, laying the blame on their Y chromosomes and ‘sex’ drive, rather than the conscious choices (drunk or otherwise) that they make. While she admits there are some male victims and that they need help, the statistics attested to by the NSW Coroners Court on domestic homicides:

… found not one single case of a man being murdered by an abusive female partner in the last fourteen years. Over that time, 162 women were killed by male partners and 98 percent of them had been abused by the man who ended up killing them (141).

Although the increase in rates of homicide cited (p. 148) in reference of the George Miles case, seem to conflate the Western Australian and national statistics. To clarify, various statistics suggest that:

… the homicide rate in Australia has been decreasing since 2005, and Australia’s homicide rate is similar to that in the UK (which, in 2011, was 1 per 100,000 compared to 1.1 in Australia). The US was most dangerous at 4.7, compared to Sweden at 0.9 (cited in Goldsworthy, 2019).

To conclude, this is how Gilmore collates the disparity between the Australian government’s spending on defense and domestic violence:

By 2017 the Australian Federal government was spending around $35 billion on national security and $160 million on domestic violence each year. If you divide that spending between the past twenty years’ worth of victims of both terrorism and men’s violence, it comes to $53 billion per person affected by terrorism and $55 per woman affected by male violence (219).

Pause to think?

1. Hilary Clinton had one child and a grandchild when she ran for president. Time magazine published a discussion of the problems she would face running for president after the birth of her first grandchild under the headline: ‘The Pros and Cons of “President Grandma”. pp. 204-205

References

Goldsworthy, T. (2019, January 24). How safe is Australia? The numbers show that attacks are rare and on the decline The Conversation Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/how-safe-is-australia-the-numbers-show-public-attacks-are-rare-and-on-the-decline-110276

Matthews, J.J. (1984). Good and mad women: The historical construction of femininity in twentieth-century Australia, Sydney: George Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

Summers, A. (2002). Damned whores and God’s police, (2nd rev.edn), Camberwell, Vic.: Penguin, Camberwell, Vic.

About the reviewer

Jane Scerri is currently in her third year of a DCA in creative writing at the University of Western Sydney. She has presented at literature and gender conferences and published short stories, poetry and academic papers. Currently working on a novel, her main interests are feminism, desire and contemporary Australian literature.