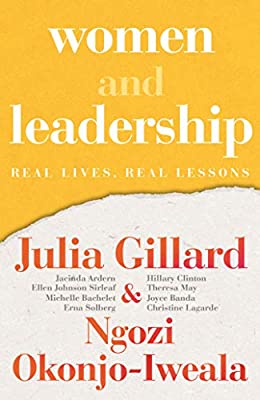

Gillard, Julia & Okonjo-Iweala, Ngozi - Women and leadership: Real lives, real lessons, Sydney, Vintage Australia, 2020, (pp. 336). ISBN 9780143794288

Reviewed by Katie Sutherland - Western Sydney University

When New York Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez took to the White House floor to discuss how she was ‘accosted and publicly ridiculed’ by a Republican representative in July 2020, her speech was both inspiring and disheartening. Inspiring because she was standing up to bigotry, disheartening because taking such a stand is still necessary.

The abuse to which ‘AOC’ referred was being called a ‘fucking bitch’ by Florida Republican representative Ted Yoho on the steps of the White House in front of reporters. She later retorted on Twitter ‘But hey, “b*tches” get stuff done’ and went on to rally a group of Democratic Party women in the House to share solidarity and their own stories. ‘I am here because I have to show my parents that I am their daughter, and that they did not raise me to accept abuse from men,’ she said. Representative Pramila Jayapal recounted how a lawmaker lashed out at her during a debate in the House, calling her a ‘young lady’ and ‘she did not know a damn thing’. Speaker Nancy Pelosi offered her own account of ‘condescending’ behaviour, telling the women, ‘I can tell you this firsthand, they called me names for at least 20 years of leadership’ (Broadwater & Edmonson 2020).

Around the same time, closer to home here in Sydney, NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard badmouthed Labor opposition leader Jodi McKay during Question Time in the NSW parliament. Hazzard mumbled ‘she’s a goose, don’t worry about her’, calling her a ‘pork chop’, ‘quite stupid’ and ‘irrelevant’ in response to questioning about the wearing of face masks for Covid-19. He began criticising her size, before thinking better of it, later apologising, saying that he was ‘tired and frustrated’. This did not, however, disguise the fact that his reflex reaction was to belittle McKay and refer to her looks. As Jacqueline Maley (2020) writes: ‘… it becomes difficult to escape the dreary conclusion that this is the lens through which we [as women] are viewed when we move through professional spaces. Still.’

‘Dreary’ indeed, tedious even. We are still here, and we still need to have this discussion, as tiring and repetitive as it is. The above examples are just two incidents that played out during the course of writing this article. Another is the announcement of Senator Kamala Harris as Joe Biden’s running mate for the 2020 US election, with The Australian publishing a poorly executed cartoon, denounced as derogatory, sexist and racist. Such real-life cases indicate that prejudice towards female politicians is not going away any time soon, and it is upon this premise that former Australian prime minister Julia Gillard and former Nigerian finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala base their book Women and Leadership: Real lives, real lessons.

AOC’s angry protest was in stark contrast to Gillard’s approach when she assumed the role of Australia’s first female prime minister in June 2010. Gillard made the conscious decision to ignore the sexism she encountered, thinking it would diminish over time. But to her surprise, it grew worse, much worse, including a profusion of shameful insults from politicians and certain members of the media. ‘Every negative stereotype you can imagine—bitch, witch, slut, fat, ugly, child-hating, menopausal—all played out’ (11). The extent of this abuse was documented and explored by Anne Summers in her 2012 Newcastle University lecture ‘Her rights at work’ (Summers, 2012).

Gillard regrets not standing up to the taunts and conduct that eventually led her to deliver her now infamous ‘misogyny speech’ in Parliament in October 2012 – a speech that still has resonance. It has become a TikTok sensation, has been sung by a choir and replicated on tea towels and t-shirts the world over.

In their book, Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala draw on their own lived experiences and those of eight other notable international leaders, all of whom they interviewed: Hillary Rodham Clinton, Jacinda Ardern, Theresa May, Christine Lagarde, Erna Solberg, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Michelle Bachelet and Joyce Banda. The inclusion of stories from leaders from a range of political persuasions and countries, including Liberia, Chile, Malawi and Norway, help ensure the research is non-partisan, cross-cultural and multi-contextual. Testing a series of hypotheses, the authors asked their interview subjects the same questions and then compared and contrasted the answers. This approach is effective, and at times the combination of voices feels as though they are having a lively conversation.

While the book challenges well-worn stereotypes, it also successfully highlights nuances by drawing on the experiences of interviewees. Choices around family life, for example, are disparate. Gillard’s decision to remain childless saw her mocked for having an ‘empty fruit bowl’ in a magazine photograph and chided by a senior conservative senator for being ‘deliberately barren’. In contrast, Theresa May, who could not have children, was treated respectfully by the media. That is not to say that members of the community were not outraged by Gillard’s treatment. She fondly recalls when, following the fruit bowl incident, a woman with ‘children in the back of her car, pulled over and yelled out in a joking manner, ‘“If you need kids, you can take mine”’ (209).

Just as support comes from the most unlikely of places, so does criticism, such as the time Germaine Greer criticised Gillard’s fashion choice on the ABC’s current affairs program Q&A, telling her that she had ‘a big arse’ and that her jackets didn’t fit. In contrast, Jacinda Ardern’s choice of clothing ‘became a symbol of love in the face of hate’ when she wore a headscarf while hugging weeping survivors at a mosque the day after the Christchurch massacre in March 2019. In this case, ‘there was a transcendent power in appearance’ (150).

As well as incorporating personal anecdotes, the authors draw on studies and theory, concluding with the chapter titled ‘Stand-out lessons from eight lives and eight hypotheses’ (274). The writing and research feel robust and current, while also practical. Meanwhile, the framework the authors have adopted would make a good model for an academic research project, including a PhD thesis.

Key hypotheses include the fact that too much attention is paid to how women look and not what they do; women are judged for their decisions around family life; and women are held to vastly higher standards than men. The latter is referred to as the ‘modern-day Salem’ phenomenon, whereby women are metaphorically tried for being witches. This analogy became uncomfortably close to the bone when Gillard was prime minister and Tony Abbott, then leader of the Liberal-National Party opposition, stood next to a sign that read, ‘Ditch the witch’ during an anti-carbon ‘tax’ protest. Similarly, when ‘… a bombastic Australian radio personality called for [Gillard] to be “put in a… bag and dropped out to sea”, Gillard grimly joked that clearly he was failing to understand that you cannot drown a witch’ (235).

Such incidents are handled with grace and humour throughout the book. Although it is fairly obvious to whom the authors are referring, they do not name and shame them, instead letting quotes and actions speak for themselves. It is, however, shocking to revisit the abuse that Gillard received during her time in office. Ardern is quoted in the book as saying, ‘I saw what you went through and that was just brutal. I wonder sometimes if our environment was the same as Australia, would I have stuck it out as long’ (183).

The book’s objective, however, is not to dwell on the past, but rather, to prepare the next generation of female leaders for the systemic sexism they will encounter in the future. The authors note that ‘[t]he key lesson here is that, sadly, sexism, shaming and silencing all exist, so plan your reactions to them now’ (286).

‘Be aware, not beware’, the authors advise aspiring leaders, purporting that women need to arm themselves with strategies in order to thrive in politics and business:

It is an insult to the intelligence of women and girls to try to delude them by ignoring or minimising the challenges. That being said, we do not want anything we write to put off even a single woman or girl from aiming to be a leader. Our message is the exact opposite of beware. Rather, it is GO FOR IT! And yes, we are SHOUTING. That’s how strongly we feel about the need for women, all their diversity and in record numbers, to aim to be leaders in every field (274).

As highlighted earlier, the book’s thesis is not necessarily a new one – after all, women leaders have been campaigning for equality since the Suffragettes – but the relentlessness of the message is in fact the point. Quite simply, the book’s premise is based on the feminist philosophy that every child should be ‘endowed with the same rights and opportunities … None should encounter extra obstacles if they aim to become a leader’ (39).

The authors also ask men to call out sexism when they see it (something else Gillard wishes she had sought while in office), and for journalists, both male and female, to check their unconscious bias in reporting. Excerpts from the book would make good reading for journalism students with practical tips such as replacing a female politician’s name with a generic male one to see if it describes their clothing choice, marital status or number of children. Journalists are also advised to be wary of using such words as ‘shrill’ or ‘unlikeable’, fulfilling the trope ‘she’s a bit of a bitch’ or other stereotypes. (A review of Jane Gilmore’s book Fixed It which addresses this problem, is published in this GMJ edition).

While the authors call on the media to set the standard, they also ask community members to push back when they see gender bias on social media or elsewhere – for everyone has a part to play and there is still much work to be done.

Works Cited

Broadwater, L., & Edmondson, C. (2020, 23 July). A.O.C. Unleashes a Viral Condemnation of Sexism in Congress, The New York Times, Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/23/us/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-sexism-congress.html

Maley, J. (2020, August 7). Hazzard’s attack confirms what many women suspect: contempt is close to the surface The Sydney Morning Herald, Retrieved fromhttps://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/hazzard-s-attack-confirms-what-many-women-suspect-contempt-is-close-to-the-surface-20200807-p55jid.html

Rogers, J. (2020, August 14). The Australian’s racist Kamala Harris cartoon shows why diversity in newsrooms matters, The Conversation, , Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/the-australians-racist-kamala-harris-cartoon-shows-why-diversity-in-newsrooms-matters-144503

Summers, A. (2012). Her rights at work: The political persecution of Australia’s first female prime minister (R-rated version). Retrieved from http://annesummers.com.au/speeches/her-rights-at-work-r-rated/

About the reviewer

Dr Katie Sutherland is a tutor and researcher in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts at Western Sydney University. She has a background in journalism and communications and has had articles published across a variety of Australian newspapers and magazines, academic journals and websites, including in a previous edition of GMJ Au. Her current research interests include illness and wellbeing, disability, foster care, and media and cultural representations of these. Her Doctorate of Creative Arts thesis, completed through the WSU Writing and Society Research Centre, involved researching and writing an exegesis and a creative non-fiction book about autism.