Creative Outsiders: Creative Industries in Greater Western Sydney

Katrina Sandbach

Western Sydney University, Australia

Abstract:

Greater Western Sydney is often portrayed as a cultural wasteland and appears to have been overlooked in official reports about creative industries activity in NSW. Yet a creative boom is occurring across the region shown through a diverse range of initiatives occurring between artists, community, and corporate sectors. Examples can be found in local government initiatives such as Penrith Council’s ‘Magnetic Places’ and the Penrith Progression plan for action, as well as Parramatta’s ‘creative city’ agenda. In addition to this, there are noticeable clusters of creative practitioners, organisations, and business enterprises based in the region. This paper presents a collective case study of emerging creative clusters in Greater Western Sydney suggesting that this should have implications on future policy and strategy development concerned with creative industries statewide.

Introduction

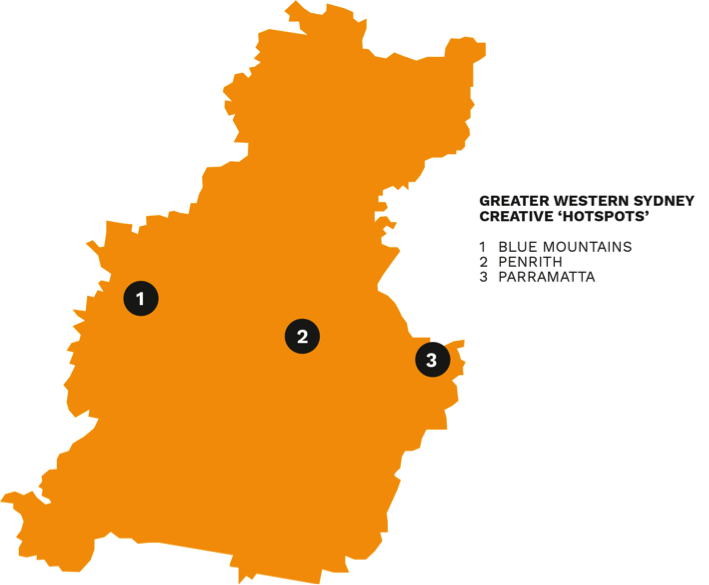

The name ‘Greater Western Sydney’ is used to describe an expansive geographic area (Fig 1) comprising the local government areas of Auburn, Bankstown, Blacktown, Blue Mountains, Camden, Campbelltown, Fairfield, Hawkesbury, Holroyd, Liverpool, Parramatta, Penrith and Wollondilly (Western Sydney University, 2015).

Figure 1: Map of Greater Western Sydney shown in relation to central Sydney.

Image: Katrina Sandbach

Greater Western Sydney has recurrently been portrayed by the media as a cultural wasteland, the ugly ‘other’ Sydney that is:

… the repository for all those social groups and cultures which are outside the prevailing cultural ideal: the poor, the working class, juvenile delinquents, single mothers, welfare recipients, public housing tenants, Aborigines, immigrants from anywhere but particularly Arabs and Asians. (Powell, 1993, p.xviii).

Ho (2012) explains that while negative perceptions of Western Sydney are starting to shift, and situated creative programs have produced a wide range of cultural expressions, this is gaining most traction at a local level, with their impact dissipating with distance. This suggests that the potential of Greater Western Sydney as a new and exciting centre of creativity may not be recognised by people outside the region. Sure enough, the NSW State government’s extensive report ‘NSW Creative Industries Economic Profile’ appears to be focused on central Sydney where ‘the largest and hottest area of creative activity is’ (NSW Trade & Investment 2013, p.18). While the report seems to base its findings on quantitative demographic and economic data, it is unclear whether this investigation of creative industries activity referred to as being in ‘Sydney’ includes or omits Greater Western Sydney. Whatever the case, the report emphasises central Sydney, which is consistent with the geographical focus of creative industries analysis that has typically been on cities – places that are dense, bohemian, urban, culturally diverse – where clusters of creative workers thrive (Florida, 2002). This overlooks the reality that in Australia and many other countries like the United States and Canada, cities are highly suburbanised (Felton, 2012). In the past, suburbs have been represented by an array of negative stereotypes such as poor aesthetics and mediocrity, and in contrast to the hip, creative and culturally rich inner city areas, the outer suburbs are seen as boring, homogenous and uncreative (Flew, 2012; Gibson & Brennan-Horley, 2010). However such views are no longer relevant to the contemporary Australian suburb (Johnson, 2012). In Australia there is a trend that now sees the suburbs as places of ‘demographic plurality and social and economic complexity’ (Gibson & Brennan-Horley, 2006; Gleeson, 2002; Randolph, 2004 in Felton, 2012, p.13) and this is echoed in Sydney’s west which is culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse (Collins & Pointing, 2000; Gwyther, 2008).

The literature shows that investigations using mostly quantitative methods and assumptions about creative cities are questionable for places that are not cities – such as the conglomerate region of Greater Western Sydney which is made up of urban, suburban, and rural locales. This paper will therefore present creative industry clusters in Greater Western Sydney as a collective case study to draw attention to activity taking place outside of central Sydney. In doing so it will suggest that more qualitative research and evaluations on the ground level would make an important contribution to government-led initiatives to develop the creative economy in NSW.

Understanding the creative industries

Promoting the creative economy has become the new mantra of urban policy (Pratt, 2010). Indeed in Australia, the Australian Government developed a formal strategy that recognized:

… that a competitive creative industries sector is vital to Australia’s prosperity – that a creative nation is a productive nation (Ministry for the Arts, 2011, p.2).

There is however slight discord in how the literature describes creative industries, and the definition of Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation (CCI) clarifies that it comprises of six segments: software and digital content; advertising and marketing; architecture, design and visual arts; music and performing arts; film, television and radio; publishing (Higgs et al, 2007, p.7). Official statistics such as Australia’s national Census have been notoriously imprecise in grasping the nature of the creative industries (Cunningham, 2011) and in response to this, CCI developed a ‘creative trident’ methodology to address deficiencies in official statistics covering the creative economy. The methodology was named as such because it pointed to three parts of the creative industries sector comprised of:

- specialist creatives – those employed in creative occupations in creative industries;

- support workers – those employed in creative industries, but in non-creative occupations and;

- embedded creative – those employed in creative occupations, but in industries that do not produce creative products (Centre for International Economics, 2009, p.19).

The creative trident approach continues to be used to sharpen the analysis of creative industries, acknowledging that previous studies have underestimated the impact of some creative sectors by up to 40% (Cunningham, 2011). While a clearer definition of what constitutes creative industries has now been reached by CCI, past inaccuracies in measuring creative industries and the sector’s growth over time suggest that there is value in qualitative research that focuses on what is happening on the ground, to enable deeper insight into the impact and potential of creative industries in NSW.

Creative outsiders: a collective case study

The government describes Greater Western Sydney as a large, dynamic region, characterised by a diverse community, a growing economy and a unique natural environment, with a population of around 2 million people (NSW Government, 2012). Among the key findings of the Centre for International Economics’ creative industries analysis is that Australia’s creative workforce was most highly concentrated in New South Wales (Centre for International Economics, 2009), where the creative industries made up 4.7% of total employment in the state (NSW Trade & Investment 2013). This suggests that Greater Western Sydney has the potential to develop into a considerable creative entity, and in 2012 arts commentator David Williams described a booming creative scene in Western Sydney that was ‘ready to kick off into the major league’ (Williams, 2012).

Indeed, in Greater Western Sydney there are a number of creative institutions, organisations, and practitioners who live and work in the region, and NSW Government Trade and Investment describes the creative and cultural environment as strong and vibrant (2015). Well-established cultural institutions such as Parramatta Riverside Theatre, Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest and Casula Powerhouse have been been key players in the development of cultural life in the region, joined more recently by others such as Blacktown Arts Centre, Joan Sutherland Performing Arts Centre, and Campbelltown Arts Centre. In addition to these highly active institutions, there are smaller creative enterprises present in the region. In accordance with the CCI definition, a database of visual communication design practitioners living and working in Greater Western Sydney has been developed by the author, and while this research is still in progress through an action research doctoral study, preliminary findings indicate that there are creative industries clusters situated around Greater Western Sydney, and the most established and active is located in the outer reaches of the region, up in the Blue Mountains. This is supported by Gibson and Brennan-Horley (2012), whose longitudinal analysis of Sydney’s creative workers using Census data revealed a high increase of creative workers in the Blue Mountains between 1991–2001.

The Blue Mountains have long been recognised as a creative hub (Blue Mountains Economic Enterprise, 2014) and a magnet for ‘creative types’ (Higson, 2012), over time carving a reputation as a creative place, where informal communities of practice (Lave and Wenger, 1991) formed organically, producing an array of networks and events that reflected the well-established bohemian visual and performing arts community. Anecdotal evidence suggests that recent population growth in the Blue Mountains has resulted in an increase in the number of creative professionals with young families migrating from the city, drawn to the established creative ‘vibe’, resulting in an expansion in the range of creative workers living and working in the Blue Mountains. In 2009 a small group of publishing and design practitioners who met at a local economic forum formally established a non-profit organisation ‘Publish! Blue Mountains’ as an umbrella brand to facilitate collaboration, professional development, raise the profile of members, contributing to the growth of the local economy (Publish!, n.d.). The popularity and activity of Publish! was noticed by the Blue Mountains Economic Enterprise (BMEE), who saw its potential and sought seed funding from the Blue Mountains City Council in 2013 to support the group’s growth. This resulted in the Blue Mountains Creative Industries Cluster (BMCIC) initiative, with the main objective to formally develop a creative industries cluster that would ‘increase the productivity and competitiveness of this industry and further diversify the local economic base of the Blue Mountains’ (Blue Mountains Economic Enterprise, 2014). BMCIC hit the ground running in 2013 with a regular series of talks, networking evenings, and one-on-one consultations with the official Creative Cluster Manager, who was appointed to facilitate synergies between practitioners and identify industry strengths, needs, and aspirations. From this initial investigation came the discovery that there was a concentration of screen media professionals in the Blue Mountains, hinting at the potential to hone in on this particular aspect of creative industries and develop it into a regional strength. As a result, the first BMCIC event of 2014 was oriented towards mustering film and animation practitioners, and in attendance were local writers, costumers, animators, directors, producers, 3D modelers, voiceover artists, actors, digital effects specialists, designers, event managers, musicians, composers, and sound designers. From this event, several film projects went into production in the Blue Mountains during 2014.

As a Blue Mountains resident and creative practitioner, the author is involved with BMCIC, with a personal stake in what eventuates, and in a privileged position to observe this scenario unfold on the ground level. Anecdotally, the Blue Mountains creative community is supportive of diversifying the local economy, which is currently largely reliant on tourism and hospitality. However, there is also some scepticism about the initiative being funded and operated from the top-down. In any case, BMEE has strived to facilitate a participatory process – these developments aren’t happening ‘around’ or ‘to’ creative people in the mountains, but instead ‘with’ them. Reflecting this, in 2015 BMEE launched the Blue Mountains Creative Industries Cluster Branding and Positioning Project, inviting creative professionals and firms based in the Blue Mountains to submit proposals, with the goal to position ‘the Blue Mountains as a hub of creative excellence’ that attracts clients and investors (BMEE, 2015), and an official brand ‘MTNS MADE’ to represent Blue Mountains creative industries – devised by local practitioners – was launched in November 2015. Through their establishment of the inaugural Blue Lab Creative Industries Symposium held in May 2015, BMEE signal that they are serious about putting the Blue Mountains creative industries on the map. The BMCIC’s regular monthly gatherings continue to bring together ‘regulars’, indicating that in the Blue Mountains, local government and community are committed to sustaining and growing the local creative economy.

At the base of the Blue Mountains, graphic design entrepreneur Debbie O’Connor held a long-term goal to house local creative industries in one space – emulating the trendy inner-city practice of ‘co-working’ (Neuberg, 2005) in renovated warehouses. The Creative Fringe opened its doors to the community in 2014, with a vision to create something more than a co-working space; to harness and share ‘the collective energy of creatives and encourage communication, collaboration and innovation’ (The Creative Fringe, 2014), and to increase recognition of the ‘many more talented and creative people out in Sydney’s West’ who ‘aren’t showcased enough’ (O’Connor, in Tarbert, 2014). In addition to providing amenities, The Creative Fringe offers a range of professional development workshops called Fringe Benefits, harnessing the expertise of practitioners based locally and beyond who might not have previously had access to such a venue outside of central Sydney.

The idea of a developing a creative hub like Creative Fringe also emerged in Penrith Progression’s recent ‘Ideas and Opportunities’ workshop held in August 2014, which identified the growth of Penrith’s creative and digital media economy as a high priority project centred around the establishment of a major cultural institution over the next 2-5 years. Launched in 2014 as a joint initiative between Penrith Business Alliance and Penrith Council, the key goals of Penrith Progression are to ‘revitalise the Penrith city centre, attract investors and create thousands of local jobs’ (Penrith Progression, 2015), and through a collaborative process that engages stakeholders and local community, it plans to develop frameworks for economic and place-shaping development to be activated over the next 10-15 years. In addition to attracting creative hubs, the creative sector was repeatedly identified by workshop participants as being key actors in the acceleration of a variety of initiatives spanning shopping, education, and also the re-branding of Penrith itself, to counteract cultural snobbery about the west (Penrith Progression, 2014).

Further east in Parramatta, the local council has been implementing a creative city strategy since 2007 centred on a ‘Pop Up’ Parramatta program. This was inspired by the successful Renew Newcastle project that was credited with revitalising Newcastle’s empty commercial centre by facilitating partnerships between landlords and local creatives requiring space to work/exhibit/sell their work (Renew Newcastle, 2015). Jointly funded by Parramatta City Council and the NSW Government, the aim is to:

… profile Parramatta as a leader in the creative industries, renew city spaces, promote the region, build and promote the creative community and to stimulate and support creative enterprise (Parramatta City Council, 2014).

Urban planner, Western Sydney Director of the Sydney Business Chamber, and former Lord Mayor of Parramatta David Borger, explained that the greatest challenge for Parramatta has been ‘to curb the brain drain of our creative young people to the bright lights and urban villages of Sydney, to counter outdated images that Western Sydney is some kind of cultural desert’ (Borger, 2007, June 14). More recently Borger (2015, February 25) argued that despite the best efforts of local councils doing the ‘heavy lifting’, underinvestment in Western Sydney arts at state level is holding back the region creatively.

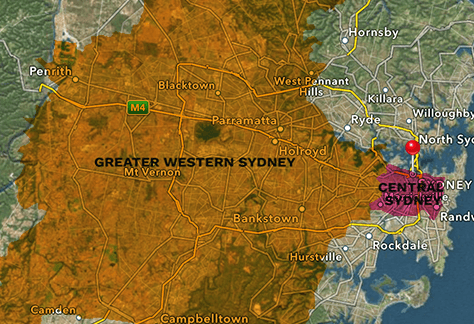

Nonetheless, Parramatta’s creative push, in addition to Penrith’s Creative Fringe and the Penrith Progression initiatives as well as Blue Mountains’ creative cluster (Fig 2), signal that Western Sydney’s creative industries are consolidating in particular locations, and have the support of local government.

Figure 2: Map showing Greater Western Sydney’s creative hotspots in the Blue Mountains, Penrith, Parramatta.

Image: Katrina Sandbach

In addition to this in 2012, Sydney Festival, one of Sydney’s most revered cultural institutions traditionally confined to the inner-city, launched a busy art, film and music program based in the Western Sydney reflecting a growing and culturally hungry population (Schwartzkoff, 2012). The 2015 festival saw the largest ticketed Parramatta program to date, drawing large audiences from across the Sydney region (Sydney Festival, 2015, p.44). Established for far longer in the west is the Sydney Writer’s Festival, the third largest of its kind in the world, with an extensive suburban program reaching as far as the Blue Mountains and also regional NSW (Arts NSW, n.d.). It also isn’t a case of tokenistic programming – Sydney Festival’s Parramatta line-up and Sydney Writer’s Festival’s Blue Mountains bill are both substantial and comprehensive, and high attendance figures suggest that there is a strong creative appetite among the residents of Greater Western Sydney. The proliferation of the outer city satellite programs for both events indicate these creative institutions acknowledge the importance of engaging with audiences beyond the city, and that the people of Greater Western Sydney are enthusiastic about engaging with creative programs. Contrary to Borger’s suggestion that underinvestment in Western Sydney arts at a state level is holding the region back creatively, it is possible to view the increased presence of state cultural institutions and festivals such as Sydney Festival and Sydney Writer’s Festival in the west as a reflection of the NSW Government’s belief in the region’s potential, evidenced by the Western Sydney Arts Strategy that was launched in 1999. As a result of the strategy, local investment in the arts was mobilised and it is now standard for local councils to employ cultural development officers and develop annual cultural plans (Ho, 2012, p.42). Fifteen years on, Ho highlights that while advocates now ‘hail the region as Australia’s newest cultural sensation’ (2012, p.35), and positive images and stories of cultural vibrancy have gained traction within the region, they have done little to shift external perceptions of the West. This is an important issue that continues to affect how people from Western Sydney socially and economically interact with other Sydney-siders (Sandbach, 2013), which may inhibit the region’s growth in the creative sector unless it is pro-actively addressed.

Practices of creative intervention in Greater Western Sydney

While creative industries clusters have only recently been identified in Western Sydney, there is an established practice of creative intervention in the region. Early settlement in Greater Western Sydney during the 1960s and 1970s depended on low-income families drawn from the inner city by the promise of affordable housing in far-flung places (Guppy, 2005). From the onset, stories of neglect, poverty and unrest in the subsidised housing estates of Mount Druitt and Macquarie Fields were the focus of negative media stories (Gwyther, 2008), paving the way for widespread criticism of the area, fixating on the desperate, hostile people ‘living on the edge’, referred to shorthand as ‘Westies’– pictured as a crude, disadvantaged people (Powell, 1993).

To tackle this initial flush of negative imagery, local government recruited various experts to develop cultural projects that would provide residents the opportunity to redefine their suburban landscape. Through these programs, alternate cultural identities for Western Sydney began to emerge and become recognisable, and during the 1990s ‘Western Sydney began a process of redefinition, from the ubiquitous ‘other’, a place not considered ‘cultural’ by inner Sydney, to a region with new and distinctive cultural possibilities’ (Guppy, 2005, p.1). Furthering this kind of work today is Information and Cultural Exchange (ICE), a Parramatta-based organisation specialising in digital media and community cultural development. Through digital storytelling, film, and music, ICE works mainly with young people from migrant and refugee backgrounds, not only providing them with previously inaccessible platforms for creative expression, but also providing training, mentoring, networking opportunities and professional development (Information Cultural Exchange, 2012). ICE projects have built the career foundations of some highly successful Australian artists, and have also been at the forefront of ‘forging a particular Western Sydney model of cultural expression’ (Ho 2012, p.42). ICE programs are participatory, empowering ordinary people to tell their own stories, reframing residents of Western Sydney as cultural producers, and shifting ‘stereotypes of the area as deprived and culture-less, as well as creating new ways of expressing cultural identity that valorise diversity’ (Ho 2012, p.49). This highlights the importance of local perspective in the re-imagining of places through participatory methods, as discussed by Pink et al. (this issue).

Some municipalities in Greater Western Sydney have also embraced participatory place-making approaches (Legge, 2008), such as Penrith Council’s Neighbourhood Renewal Program, which spawned ‘Art Everyday’ and ‘Magnetic Places’, the latter giving financial support to organisations and individuals to devise community-based creative projects spanning public art, film, photography, music and theatre. Such projects ‘transform existing places in neighbourhoods into creative spaces for residents to connect, share stories and contribute to a vibrant City’ (Penrith City Council, 2015).

Discussion

While it is evident that creative interventions have effected positive change within Greater Western Sydney, and that creative hotspots are emerging in the region through the increased presence of industry clusters, the activity of creative industries has a tendency to be (inaccurately) measured by quantitative measures, favouring broad-spectrum economics rather than pragmatically analysing activity on the ground level.

If Australia, and specifically NSW, is serious about supporting the growth of creative industries, it is crucial that sharper and more holistic indicators of creative industries are developed, so that policy and strategy may be situated – and tailored accordingly – rather than using a one size fits all approach that may be doomed to failure ‘as we know that the same policies produce different effects and impacts under various institutional and social, cultural and economic contextual situations’ (Pratt, 2010, p.5). More research into Greater Western Sydney creative industries by the author is forthcoming, but there is a growing body of literature challenging the ‘imagined geographies’ of creative place thinking that assume the inner cities are the centre of creative industries (Collis et al., 2013, p.149). The reality in Australia is that there are active creative industries situated outside the urban core (see Felton et al, 2010a; Felton et al., 2010b; Flew, 2012) – such as those in Greater Western Sydney – that have different challenges, characteristics, needs and aspirations that should be factored into policy and strategy development.

Recommendations

Western Sydney University is ideally positioned to spearhead initiatives that are concerned with creative industries development Greater Western Sydney. What we already know from research undertaken in the United Kingdom is that higher education institutions are key actors in developing sustainable local creative economies through providing infrastructure, as well as educating or attracting and retaining skilled workers (Comunian & Faggian, 2011). This is evident in the growth of creative areas such as New York’s Garment District that is largely attributed to its interaction with Parson’s School of Design, and more recently the Queensland Institute of Technology’s recoding of Brisbane as a Creative Industry Precinct. With Parramatta’s ‘creative city’ policy in action, there are avenues through which Western Sydney University can drive place-oriented creative development in Greater Western Sydney. This is shown by the following ideas that have arisen in this paper:

- Expand the offering of creative education programs to develop ‘home grown’ talent, and Greater Western Sydney creative communities of practice in-situ.

- Provide centralised or satellite creative workspaces, mentoring, and other support frameworks for early career creatives who might otherwise leave the region for education or employment.

- Engage with local creative industries and develop cooperative projects with an emphasis on shifting long-standing negative perceptions of Greater Western Sydney.

- Develop a greater understanding of the intrinsic value of creative programs in Greater Western Sydney and share this with the community, laying foundations for future capacity building.

Conclusion

This paper has shown that in Greater Western Sydney, creative interventions, events and initiatives are gaining traction, and situated industry formations signal an even more vibrant region in the near future, where creative industries input across a range of different sectors of the region’s social, cultural, and economic life. This should no longer be left purely to chance, but instead pro-actively facilitated in order to drive innovation and economic growth in the region; Western Sydney University has a valuable role to play in this process.

References

Arts NSW. (n.d.). Retrieved April 12, 2015 from http://www.arts.nsw.gov.au/index.php/arts-in-nsw/major-festivals/sydney-writers-festival/

Blue Mountains Economic Enterprise. (2014). Creative industries. Retrieved from http://bmee.org.au/industry-development/creative-industries/

Blue Mountains Economic Enterprise. (2015). Creative industries branding project EOI. Retrieved from http://bmee.org.au/about/eoi/

Borger, D. (2007, June 14). A creative city with a need to keep it that way. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/a-creative-city-with-a-need-to-keep-it-that-way/2007/06/13/1181414376704.html

Borger, D. (2015, February 25). Underinvestment in the arts is holding Western Sydney back. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/comment/underinvestment-in-the-arts-is-holding-western-sydney-back-20150225-13ojss.html

Centre for International Economics. (2009). Creative industries economic analysis final report. Prepared for Enterprise Connect and the Creative Industries Innovation Centre. Retrieved from http://apo.org.au/research/creative-industries-economic-analysis-final-report

Collins, J., Poynting, S. (2000), Introduction. The other Sydney: Communities, identities and inequalities in Western Sydney. Haymarket: Common Ground Publishing, 1-18.

Collis, C., Freebody, S., & Flew, T. (2013). Seeing the outer suburbs: Addressing the urban bias in creative place thinking. Regional Studies, 47(2), 148-160.

Comunian, R., Faggian, A. (2011) Higher education and the creative city. Creative cities handbook. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. 187-210.

Creative Fringe. (2014). About. Retrieved from http://thecreativefringe.com.au/about/concept/

Cunningham, S. (2011). Developments in measuring the ‘creative’ workforce. Cultural Trends, 20: 1, 25-40.

Felton, E. (2012). Working in the Australian suburbs: Creative industries workers’ adaptation of traditional work spaces. City, Culture and Society, 4, 12-20.

Felton, E., Collis, C., & Graham, P.(2010a). Making connections: Creative industries networks in outer-suburban locations. Australian Geographer, 41(1), 57-70.

Felton, E., Gibson, M. N., Flew, T., Graham, P., & Daniel, A. (2010b). Resilient creative economies? Creative industries on the urban fringe. Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 24(4), 619-630.

Flew, T. (2012). Creative suburbia: Rethinking urban cultural policy – the Australian case. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 12, 231-246.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class. New York: Basic Books.

Gibson, C, Brennan-Horley, C. (2006) Goodbye pram city: Beyond inner/outer zone binaries in creative city research. Urban Policy and Research 24: 455–471.

Guppy, Marla (2005). Cultural identities in post-suburbia. Conference proceedings, After Sprawl: Post-Suburban Sydney, Sydney. Retrieved from http://www.uws.edu.au/ics/publications/reports.

Gwyther, G. (2008). Once were westies, Griffith Review issue 20: Cities on the Edge. Retrieved from http://griffithreview.com/edition-20-cities-on-the-edge/once-were-westies.

Higson, R. (2012, November 8). Gallery for the landscape, worth a peak. The Australian. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.uws.edu.au/docview/1139682515

Higgs, P., Cunningham, S., Pagan, J. (2007). Australia’s creative economy: Basic evidence on size, growth, income and employment. ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries & Innovation, Brisbane. Retrieved from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/8241/1/8241.pdf

Ho, C. (2012). Western Sydney is hot! Community arts and changing perceptions of the west’, Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 5, no. 1, pp.35-55.

Information Cultural Exchange. (2012). What is ICE?. Retrieved from http://ice.org.au/what-is-ice/.

Johnson, L. (2012). Creative suburbs? How women, design and technology renew Australian suburbs. International Journal of Cultural Studies. 14, 217-229.

Lave, J., Wenger, E.C., (1991). Situated learning, legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Legge, K. (2008). An overview of international place-making practice: Profession or ploy?. Conference proceedings international cities, town centres and communities. Sydney. Retrieved from http://www.ictcsociety.org/PastConferencesSpeakersPapers/2008ICTCConferenceSydney/2008PublishedSpeakersPapers.aspx

Ministry for the Arts (2011). Creative industries, a strategy for 21st Century Australia. Retrieved from http://arts.gov.au/sites/default/files/creative-industries/sdip/strategic-digital-industry-plan.pdf

Neuberg, B. (2005). Coworking – Community for developers who work from home. Retrieved from http://codinginparadise.org/weblog/2005/08/coworking-community-for-developers-who.html

NSW Government (2012). Western Sydney and Blue Mountains: Regional action plan. Retrieved from https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/regions/regional_action_plan-western-sydney-blue-mountains.pdf

NSW Trade & Investment (2013). NSW creative industries: Economic profile. Retrieved from http://www.industry.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/55237/

Parramatta City Council (2014). Pop up Parramatta. Retrieved from http://www.parracity.nsw.gov.au/play/facilities/arts/pop_up_parramatta

Penrith City Council (2015). Culture and creativity. Retrieved from https://www.penrithcity.nsw.gov.au/Community-and-Library/Community/Culture-and-creativity/

NSW Government Trade & Investment (2015). Arts in Western Sydney. Retrieved from http://www.arts.nsw.gov.au/index.php/arts-in-nsw/arts-in-western-sydney-2/

Penrith Progression (2015). Home. Retrieved from http://www.penrithprogression.com.au/

Powell, D. (1993). Out west: Perceptions of Sydney’s western suburbs. St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin.

Pratt, A. (2010). Creative cities: Tensions within and between social, cultural and economic development. A critical reading of the UK experience. City, Culture and Society, 1(1), 13-20.

Publish! (n.d.). A business cluster building on the creative talents of our region. Retreived from http://www.sustainablebluemountains.net.au/imagesDB/resources/Publish-brochure-v5.pdf

Renew Newcastle (2015). About. Retrieved from http://renewnewcastle.org/about/

Sandbach, K. (2013). ‘Westies’ no more: towards a more inclusive and authentic place identity. Cescontexto: Debates, 2 (June), 724-732.

Schwartzkoff, L. (2012). Parramatta won’t have to hang around waiting for the arts any more, Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/about-town/parramatta-wont-have-to-hang-around-waiting-for-the-arts-any-more-20120115-1q1fn.html#ixzz1xH3Ee4xI

Sydney Festival. (2015). Annual review. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/comment/underinvestment-in-the-arts-is-holding-western-sydney-back-20150225-13ojss.html

Tarbert, P. (2014). The creative fringe in Penrith announced as finalist for the Champions of the West grant. Penrith Press. 23 May 2014.

Western Sydney University (2015). Greater Western Sydney Profile. Retrieved from http://www.westernsydney.edu.au/office_of_higher_education_policy_and_projects/home/reports_to_government

Williams, D. (2008). The rise of the west. Real Time Arts, no. 84. Retrieved from http://www.realtimearts.net/article/84/8934.

List of figures

Figure 1 (2015) Map of Greater Western Sydney by Katrina Sandbach

Figure 2 (2015) Map of creative clusters in Greater Western Sydney by Katrina Sandbach

About the Author

Katrina Sandbach is a designer and academic who lectures in the Bachelor of Design (Visual Communication) in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts at Western Sydney University, Australia. With a background in brand communication design, Katrina values innovation in education, with enthusiasm for online teaching tools and the potential of social media to extend the physical learning space. Katrina’s research draws heavily from her own professional design practice, which enriches her ongoing teaching practice. She is particularly interested in how visual communication principles affect learning space design, and cultural identity in Greater Western Sydney.