A tale of (at least) three reports: Agency and discourse in the Alice Springs town camps

Louise Crabtree

Western Sydney University

Vanessa Davis

Tangentyere Council, Alice Springs

Denise Foster

Tangentyere Council, Alice Springs

Michael Klerck

Tangentyere Council, Alice Springs

Abstract

The Alice Springs Town Camps are ongoing sites of Aboriginal community life, service delivery, and advocacy. As with other Town Camps throughout Australia’s Northern Territory, they are also the target of numerous program and policy reviews, as well as recurrent media attention that focuses on a variety of ills and rarely on community voices or experience. This paper works through three reports, contrasting community-based research by the authors that found the Camps are strongholds of community history, identity, and aspiration with the most recent review of the Northern Territory Camps undertaken for over $2m by a private consultancy that recommended the closure of the Camps. Between these two reports lies a third by the Public Accounts Committee of the Northern Territory Government that found serious errors in the contracting process for housing service delivery on the Camps; errors that had come at the expense of community-based service providers. The paper draws on the Town Camp community research and work by other Aboriginal communities that shows in contrast to a persistent dominant narrative of economic development as requiring the closure or privatisation of Camps, communities are already interested in and pursuing hybrid models that respect their histories and aspirations.

Introduction

The promotion of home ownership is a central objective of federal government policy regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’1 housing and land reform (see Sanders, 2008a; FaHCSIA, n.d.; COAG Reform Council, 2011). Much of that policy deploys variants on de Soto’s (2001) argument that informal settlements fail to thrive economically because residents cannot secure a legal and economic interest in their place of residence. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities already have a range of legal property regimes in place or agreed informal processes alongside property systems that could enable tenure forms meeting community aspirations. However, current policy focuses on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land reform and the promotion of ‘mainstream’ home ownership as economic development vehicles, as part of a broader discourse of ‘normalisation’ and ‘mainstreaming’ (Habibis et al., 2016).

Communities are concerned about control of their lands and the various policy imperatives they face. Consequently, that policy context has triggered discussion about current or potential secure tenure options for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ land and housing that reflect community aspirations without rendering lands vulnerable to inappropriate interests (e.g. Wensing & Taylor, 2011). Such options include models that can enable the realisation of economic assets where desired and appropriate (Wensing & Taylor, 2011; Ross, 2013; Crabtree et al., 2012a). Given that a diverse range of housing options could be developed without land reform and that much of the policy discourse regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander home ownership in the Northern Territory deploys the problematic notion and offensive language of ‘normalisation’ while not actually moving towards ‘normal’ tenure (Dalrymple, 2007), this policy push toward land reform could be read as an attempt to erase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural identity and performance (Sanders, 2008b; 2010), whether conscious or not.

Previous work on home ownership in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities has highlighted that, as with many other households, core objectives amongst those individuals interested in home ownership focus on stability, autonomy, and the ability for housing occupancy to follow cultural protocols including kinship systems. This latter issue is especially acute in instances where ‘mainstream’ models of both renting and owning can be at odds with cultural obligations following a death. Memmott et al.’s (2009) work highlights that for some communities, such concerns outweigh considerations of financial gain. Further, a growing body of work highlights that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander households and communities experience levels of unemployment and remoteness that would suggest that assumptions about wealth creation through private home ownership are misguided (see Crabtree 2014; Crabtree, et al., 2012b; Moran, Mcqueen & Szava, 2010; Sanders 2008a; 2008b). Given these issues, it would seem that alternatives to ‘mainstream’ home ownership could be relevant for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities that are interested, rather than the default deployment of models based on individual freehold title, open markets, and market-based mortgages.

This perspective parallels increasing interest within Australia and internationally in ‘intermediate’ tenure forms in the broader housing system in response to growing concerns about the diminishing affordability of housing, the impacts of predatory lending, and the need for a more nuanced range of tenure choices (see Crabtree et al. 2012b; Bright & Hopkins 2012; Whitehead & Monk 2012; McDonald 2013; Temkin, Theodos & Price, 2013; Theodos et al., 2017). Particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ housing, diverse hybrid options are warranted that recognise and respect community histories and current forms of community occupancy, and which can encapsulate and enable community and household aspirations, including the capacity for wealth creation if and as appropriate (Crabtree et al. 2012a; Crabtree 2014, Crabtree 2016a).

In that context, this paper reports on three consecutive reports on Town Camps (hereafter, ‘Camps’) in the Northern Territory (NT), focusing specifically on Alice Springs. These communities and the policy manoeuvres they are subject to highlight ongoing issues regarding how discourses about Aboriginal people’s lives, communities, and hopes are constructed, by whom, and to what ends. Alongside and amidst ongoing political machinations, ideological pronouncements, and policy churn, determined individuals, communities, and organisations find ways to influence outcomes, although the situation perhaps makes a mockery of claims to policy coherence or a regard for evidence.

Report the first: articulating community aspirations

This report presented findings of research undertaken by a team based at Western Sydney University and the Tangentyere Council Research Hub (TCRH) that jointly developed a survey of 150 households across the Alice Springs Town Camps. The survey was carried out and analysed by Aboriginal TCRH researchers, capturing Town Camp residents’ (hereafter, ‘Campers’) experiences of changes to housing management and governance under recent policy changes, specifically the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 (‘NTER’) and Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Act 2012, as well as changes to local government under the Northern Territory Local Government Act 2006.

Within this context at the time of the research, there had been significant discussion of home ownership on the Camps amongst diverse stakeholders. The survey was a critical opportunity to hear the voices of Campers, to hear what they think about home ownership and proposals for land reform. To frame discussions around future options for Camps, the survey also captured Campers’ understandings of ownership and aspirations for their households and communities.

The Alice Springs Town Camp Context

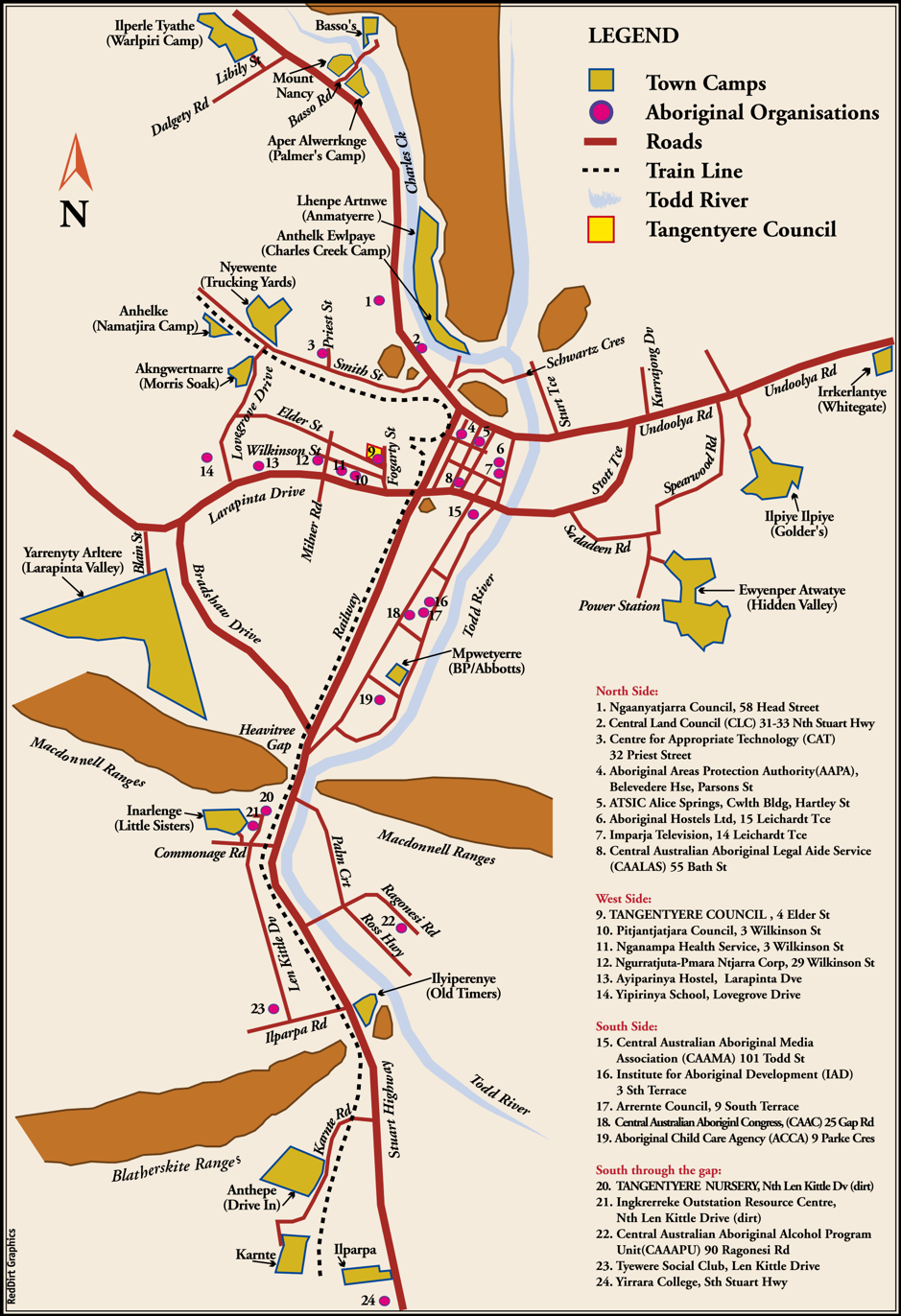

The conservative service population estimate for Town Camps is between 1,950 and 3,300 people; 70 percent are permanent residents and 30 percent are either visitors or homeless (Foster, Mitchell, Ulrik & Williams, 2005; see Figure 1 for a map of the Camps). Tangentyere Council was established to represent and service the Camps during the 1970s and was incorporated from 1979 until August 2015 under the Northern Territory Associations Act. In 2015 Tangentyere Council transferred incorporation to the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 to comply with the Commonwealth Government requirement for Indigenous Organisations to be incorporated under that Act in order to receive Indigenous Advancement Strategy funding. Tangentyere Council has 16 corporate and approximately 650 individual members, is the eighth largest Aboriginal Corporation in Australia, and in 2016 was a finalist in Reconciliation Australia’s Indigenous Governance Awards – a point worth bearing in mind.

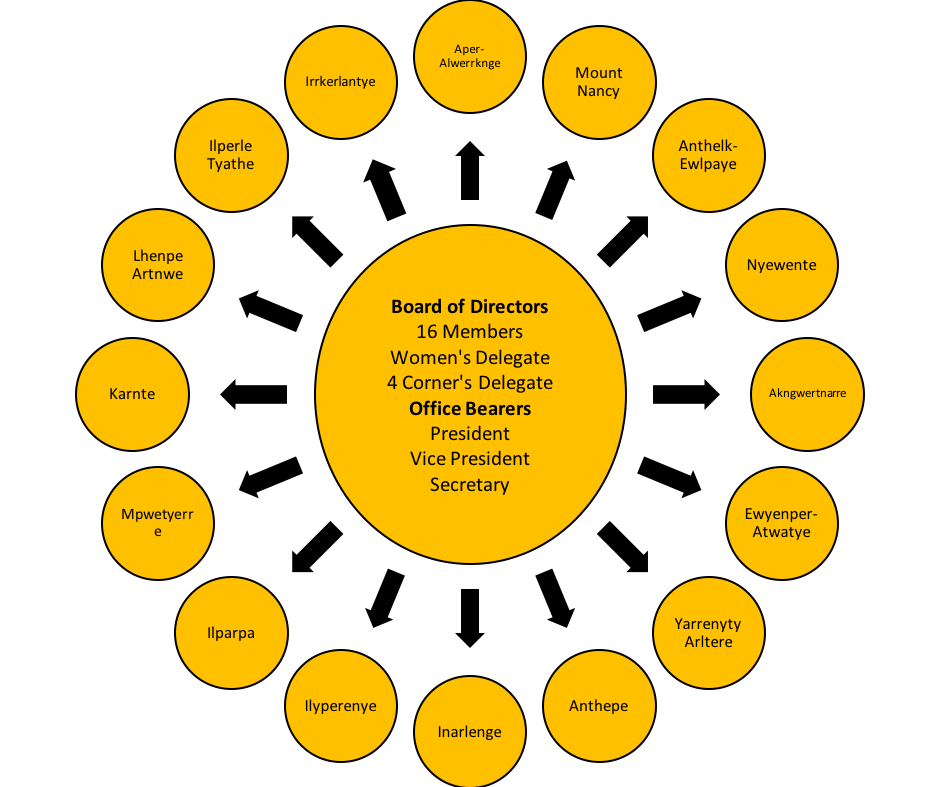

The corporate members of Tangentyere Council are the Alice Springs Town Camp Housing Associations and Aboriginal Corporations. As per Figure 2, Tangentyere Council has a Board comprised of the elected Presidents of each corporate member, a delegate from the Women’s Committee, and a delegate from the Four Corners Committee. Four Corners is comprised of senior Aboriginal law people who advise on the integration of traditional law and matters of governance responsibility. The membership of Tangentyere Council elects a President and Vice President from amongst this leadership group at the Annual General Meeting.

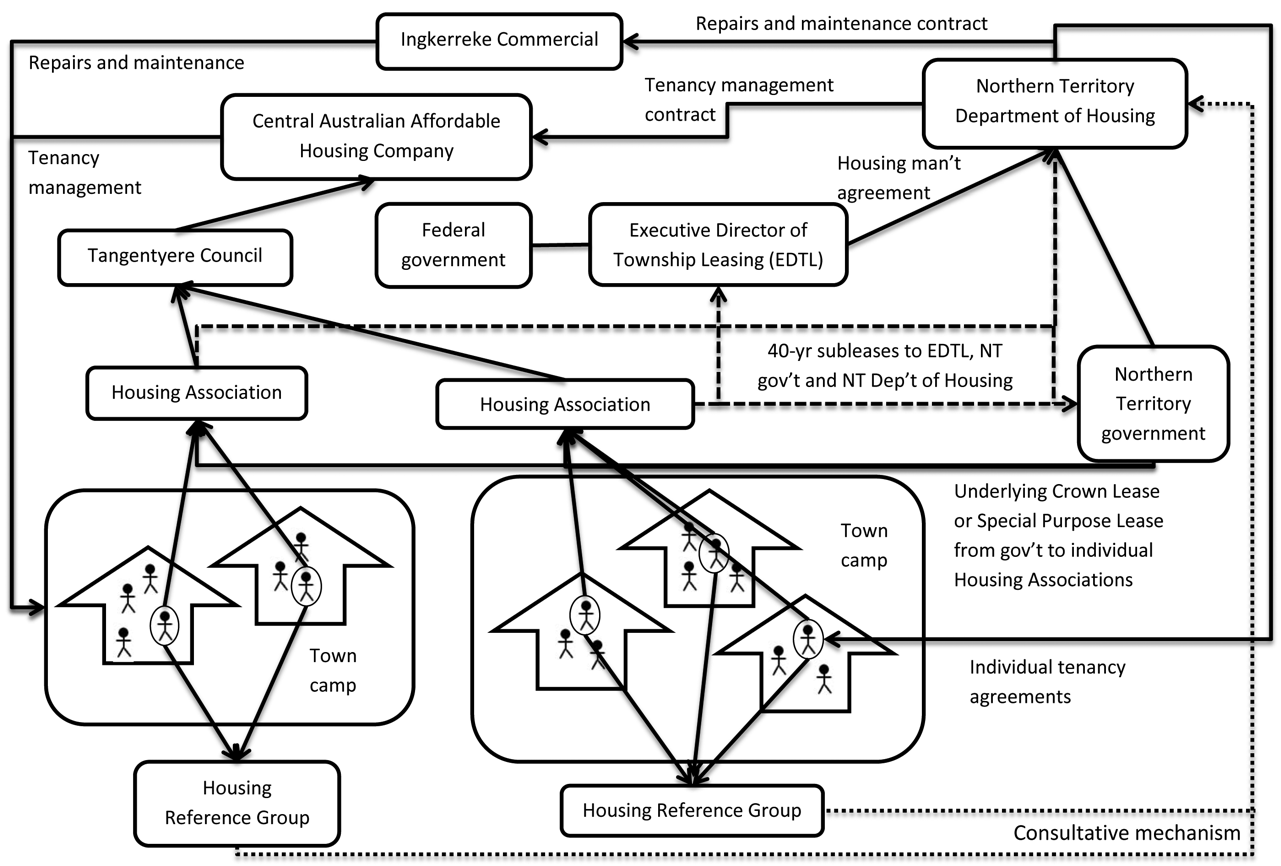

Consequent to the NTER, in 2009, 14 Housing Associations entered into 40-year tripartite Alice Springs Living Area Subleases with the Executive Director of Township Leasing (on behalf of the Commonwealth) and the CEO of Territory Housing (on behalf of the Territory Government). This was done in return for a commitment of $100 million to upgrade housing and essential infrastructure. The Executive Director of Township Leasing then entered a Housing Management Agreement (under lease) with the Northern Territory Government, which is currently the Housing Authority over Town Camp houses.

Figure 1: Map of the Alice Springs Town Camps.

Source: Foster, Mitchell, Ulrik & Williams (2005, p.7)

Figure 2: Governance structure of Tangentyere Council

Tangentyere Council, the Town Camp Housing Associations, and Aboriginal Corporations negotiated with the government over a period of two years to reach this position, after initially being offered $20 million in return for signing unconditional subleases for 99 years. Tangentyere Council remains of the opinion that essential housing and services should not have come at the price of leasehold. Weighing up the extreme level of need of Campers with the Commonwealth Government threat to compulsorily acquire the Camps if they did not sign, the Housing Associations negotiated what they felt to be the best option available at the time and agreed to sign the subleases. Ilpeye-Ilpeye Aboriginal Corporation did not sign a sublease agreement with the Commonwealth Government and as such, the Crown Lease over Lot 6911 was compulsorily acquired. Ilpeye-Ilpeye Aboriginal Corporation resigned from Tangentyere Council after making this decision.

The majority of Camps include Arrernte residents, who are the Traditional Owners of Alice Springs and its immediate surrounds, and residents belonging to other language groups with traditional lands further from Alice Springs who have moved to Alice Springs over a period of time for various reasons. Campers often have strong links with remote communities and there is substantial mobility between bush and town. While Camps are located in Alice Springs, residents are often culturally and linguistically isolated from the services available in town. Provision of services by Tangentyere Council, often in partnership with government and other non-government organisations, means that Campers can access services they would otherwise miss out on.

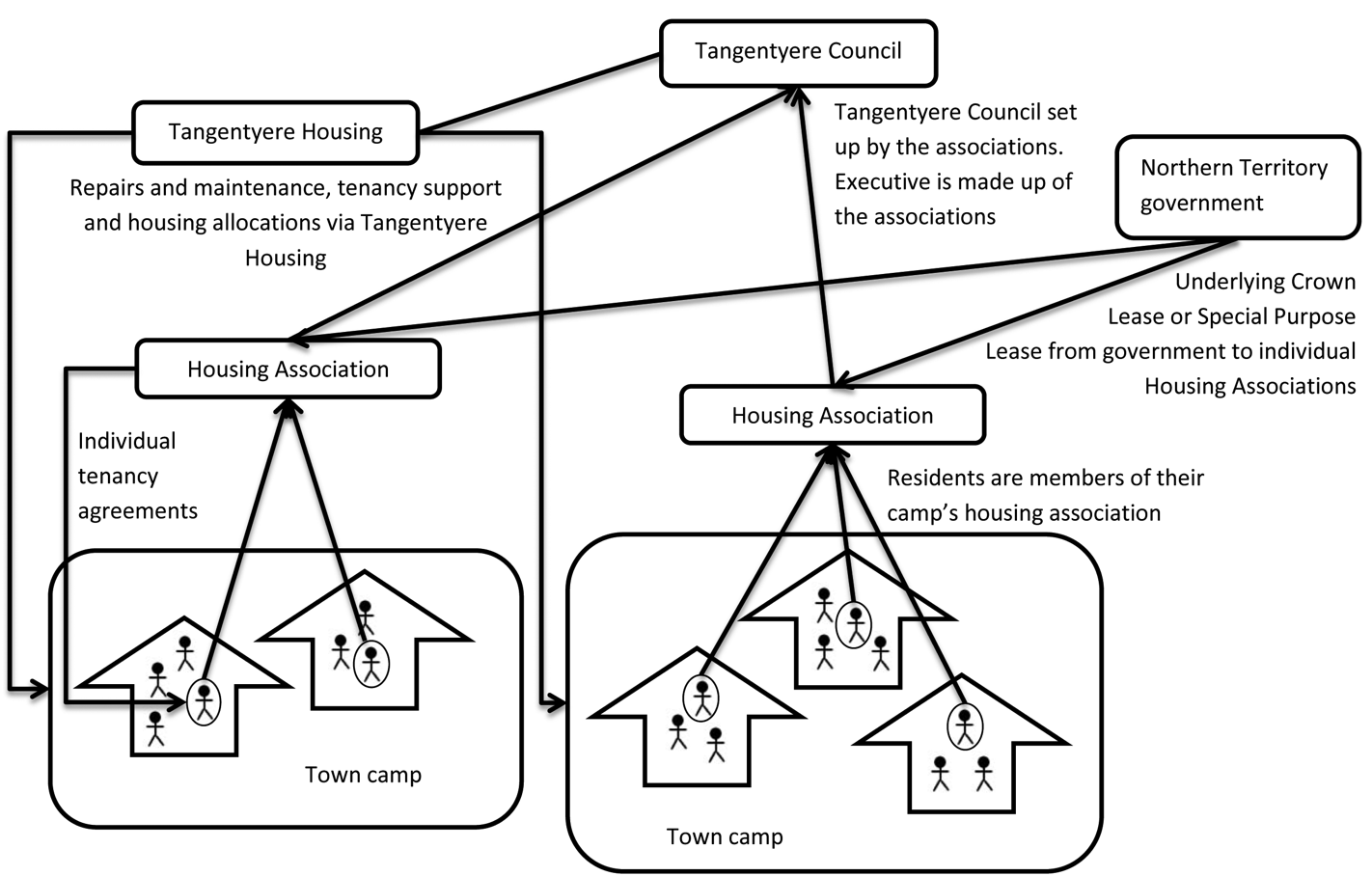

Prior to December 2009, Tangentyere Council managed 199 houses on the Camps as an Indigenous Community Housing Organisation. Since December 2009 the Northern Territory Department of Housing has been the Housing Authority for Camp housing and there has been churn through contractors selected by the Department. Over 2009-12, the Department of Housing subcontracted responsibility for both tenancy management and repairs and maintenance (‘R&M’) to the Central Australian Affordable Housing Company (CAAHC), which was established by Tangentyere Council as a separately incorporated successor to the Tangentyere Council Housing Division. CAAHC is a community controlled Public Benevolent Institution regulated by the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission and the only nationally accredited community-housing provider in the NT. Tangentyere is one of four corporate members of CAAHC together with the Central Land Council, Health Habitat, and MLCS Corporate. Both Commonwealth and Territory Governments were invited to join the governance structure of CAAHC but declined.

In 2012, tenancy management and R&M were split, with tenancy remaining with CAAHC, and R&M awarded to Ingkerreke Commercial at the expense of CAAHC and to the chagrin of the Tangentyere Council membership, many of whom were involved in the establishment of Ingkerreke to support the establishment of family outstations in the country around Alice Springs. None of the public officials interviewed for the research could clarify the logic for this separation, which meant tenancy and R&M issues were no longer addressed in an integrated manner. In February 2016, the R&M contract was awarded to Tangentyere Constructions and the tenancy contract was awarded to Zodiac Business Services, a for-profit book-keeping service believed to have connections to the politician overseeing the allocation of contracts, who took up employment with the company after leaving politics (Walsh, 2017a). In mid-2017, in the wake of the inquiry discussed below, the contract for R&M was awarded to Tangentyere Constructions and the tenancy contract was awarded to CAAHC.

Despite the changes brought by the Living Area Subleases, Campers retain land title through underlying perpetual leases and Tangentyere works with the Associations and Aboriginal Corporations to remain strong. Campers see this land as a common legacy to be handed to their children and grandchildren rather than as a speculative commodity. Through the subleases, Campers find themselves in a unique situation as both landlords and tenants. There are now three classifications of agreement directly relating to this land sitting under the Special Purpose Leases or Crown Leases in Perpetuity. Figures 3 and 4 show the governance arrangements on the Town Camps before and after the Intervention when tenancy and R&M contracts were separated between CAAHC and Ingkerreke, as this was the context within which the research was undertaken.

At the time of the research and in the above context of increasing legal and service delivery complexity, various agencies started talking to Campers about home ownership, often without the knowledge or endorsement of the Housing Associations, Aboriginal Corporations, or the Tangentyere Board. Communities found the discussions confusing and divisive, as the proposed models did not address ongoing relationships between households and Camp organisations. As a result, communities were interested in examining options that respect

Figure 3: Town Camp housing management before the Intervention.

Figure 4: Town Camp housing management between Dec 2012 and Feb 2016.

these relationships and that can enable household stability and autonomy without undermining community cohesion or rendering community land vulnerable.

Notes on method

The Camp survey was part of a larger research project looking at the relevance of housing models based on community land trust principles for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People’s housing. In line with strengths-based research and to ensure the research was undertaken appropriately (Foster, Williams, Campbell, Davis & Pepperill, 2006), the project involved and employed Aboriginal researchers and stakeholders in research governance, design, tasks, analysis, reporting, and review. Core team members co-authored this paper.

Building on prior interest and discussions with Tangentyere, a meeting was held between the University researchers and Tangentyere staff and Directors, to discuss the project and the intention to work with communities to develop appropriate methods. The Directors decided the project was worth consideration by the full Board, who decided that the best way to frame community stewardship and perpetual affordability on the Camps was to capture Campers’ experiences of housing management, governance, and Camp life before and after changes implemented under the NTER, as well as their aspirations and their understanding of ownership. This was based in a strong desire amongst the Board for Campers’ knowledge and experience to be recognised and documented, to inform appropriate tenure options and policies for the Camps, and to develop a coherent position in response to government proposals for land reform oriented towards individualised home ownership. The Board decided that a survey of 150 households across all Camps would generate a representational picture of Campers’ experiences and objectives. At the time there were 199 houses on the Camps, so the survey would cover 75 percent of households.

Tangentyere researchers were employed to co-design the survey so that it would be appropriate for Camp residents, then carry out pilot and full surveys and their analysis. As Arrernte Camp residents and trained researchers, the Tangentyere researchers are known to other Campers and are ideally placed and well versed in undertaking research appropriately amongst the Camps. The survey focused on: household characteristics; Campers’ sense of identity as Campers and sense of the Camps; Campers’ perceptions of responsibility for household and Camp decision making in the past and now, and their aspirations for this in the future; experiences of R&M; and, thoughts about renting and ownership.

Two teams of Tangentyere researchers visited the Camps on weekday mornings to visit when people were home, which was not always possible as many Campers leave home early to get children to school or get to Alice Springs before the days heated up. Researchers interviewed residents in their homes and filled out the printed questionnaire as they talked. After the survey interviews were carried out both Tangentyere and Western Sydney University (WSU) researchers tabulated and graphed the data to create the results discussed in this paper. Anonymised quotes from residents were appended to the relevant questions in the spread sheet and manually analysed for themes. At the time of the survey the federal government was building new houses on the Camps, so there were 285 houses across the Camps at the time of the survey, compared to 199 when the Board endorsed the project. As a result, the survey of 150 households represents final coverage of about 53 percent of households.

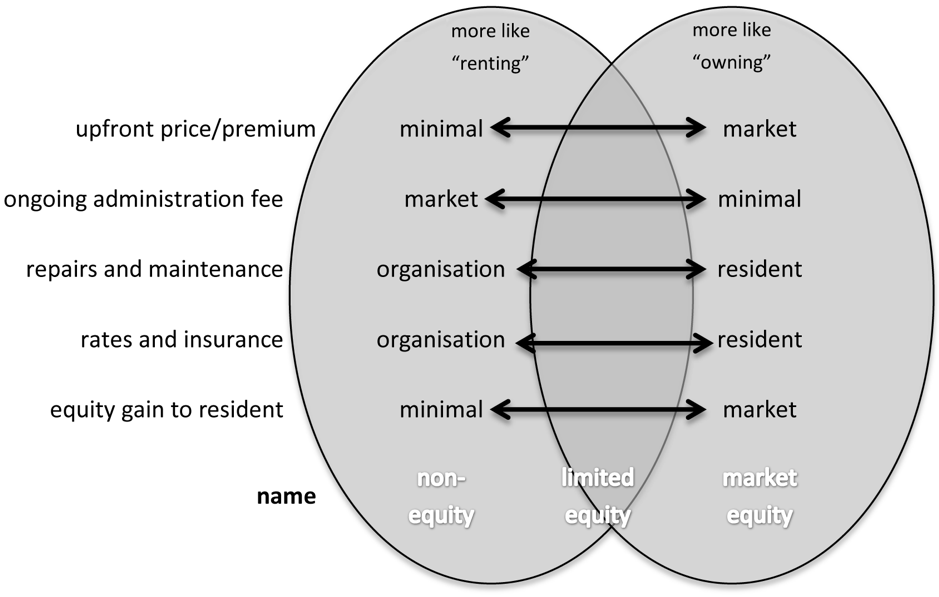

The survey included questions about whether Campers would like to own their homes and whether they knew what home ownership meant. As Camp residents, the Tangentyere researchers knew that many Campers were confused by the Federal Government focus on ownership, as they already felt they had ownership due to the Camps’ underlying perpetual leases and community governance structures. Because of this, Tangentyere researchers felt it would be useful for Campers if the team developed a brochure explaining the difference between renting and owning as understood under Western law and outlining possible forms of community ownership that might be appropriate for the Camps. The brochure was created by the full team and given to Campers at the end of their survey interview (see Figure 5). This was intended as a way to help households and communities talk about the issues raised by the reforms being proposed by the government, develop an informed position in response, and consider options that might be more nuanced than currently dominant forms of owning and renting.

The team also developed the above diagrams of the governance arrangements on the Camps before and after the NTER. Initially these were developed by the University researchers to understand the complexity of the new arrangements. Tangentyere staff clarified the diagrams, which they felt would be of benefit to communities to inform discussions concerning governance, so the diagrams were made available for circulation. They have been utilised extensively by communities and included in submissions to the Northern Territory housing inquiry discussed below; the inquiry’s report used the diagrams in discussing the complexity of arrangements implemented under the NTER. Since the original research, they have been revised each time the contractual arrangements on the Camps have been changed by the NT Government.

Overview of findings

Housing, community, and identity

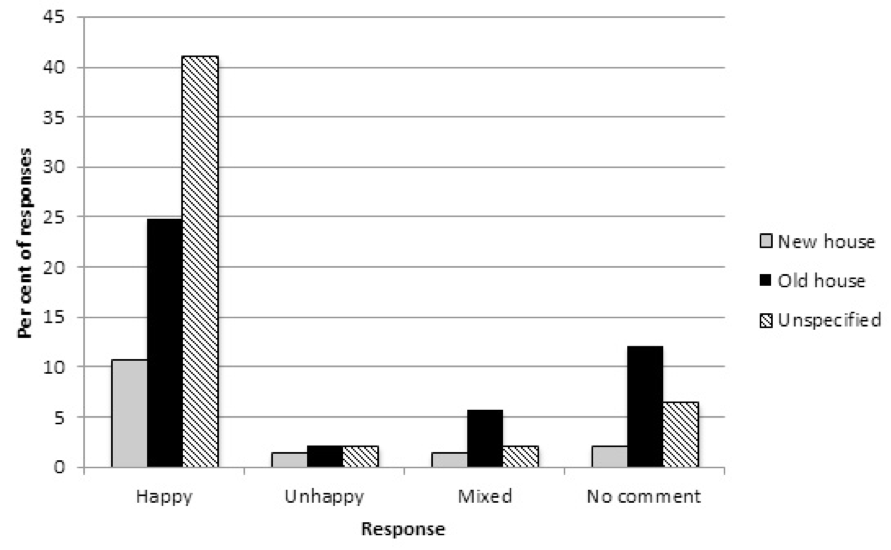

As shown in Figure 6, the majority of Campers were happy with their housing, irrespective of whether it was newly built or old stock. Notably, when Campers explained their satisfaction with their housing, responses focused on qualities of the Camp as a whole or happiness at being near family almost as much as on the physical characteristics of the house.

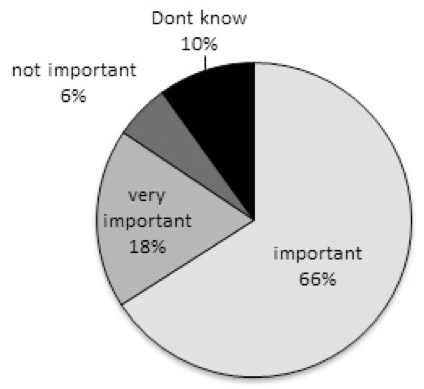

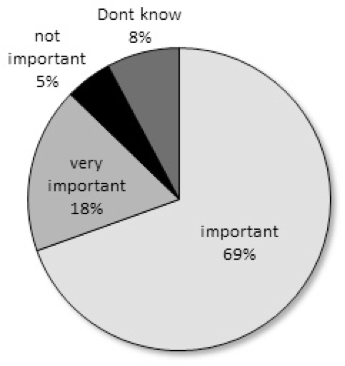

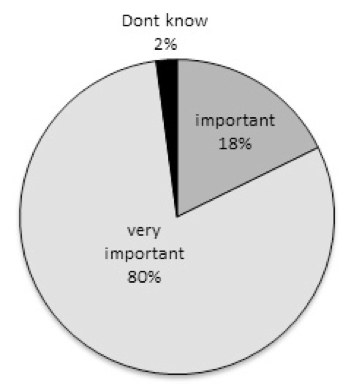

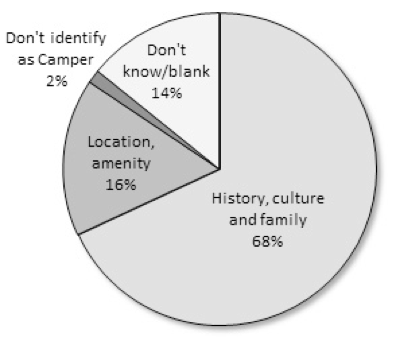

Figure 7 shows the majority of Campers felt their identity as Campers was either important (66 percent) or very important (18 percent). Similarly high numbers stated that their ability to live on a Camp was either important (69 percent) or very important (18 percent) to them (Figure 8). Campers also feel that cultural obligations are either very important (80 percent) or important (18 percent) (Figure 9 ). As seen in Figure 10, when asked about the factors underpinning the importance of being a Town Camper, the majority of respondents attributed this to either issues of family, history, and culture (68 percent), or of location and amenity (16 percent).

Figure 5 : Housing terminology brochure /

Figure 6: Town Campers’ satisfaction with their housing |

Figure 7: Importance of identifying as a Town Camper |

Figure 8: Importance of living on a Town Camp |

Significantly, many of these issues overlapped, so amenity was often talked about in terms of satisfaction at having family nearby and being able to meet cultural obligations. Much significance was placed on having space, privacy, and cultural autonomy while also being close to the support services of Alice Springs – all of these factors were often referred to as creating a comfortable environment. Taken as a whole, the responses to these questions highlight the interwoven nature of family, history, and culture in the identity, practices, and living places of the Campers, which are intricately bound up in community governance structures.

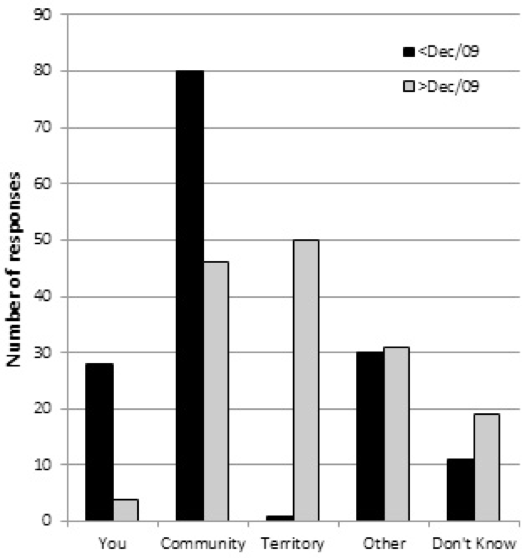

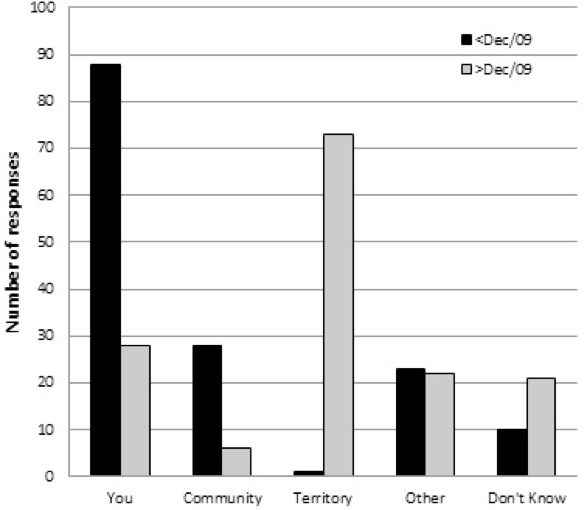

Decision-making and governance

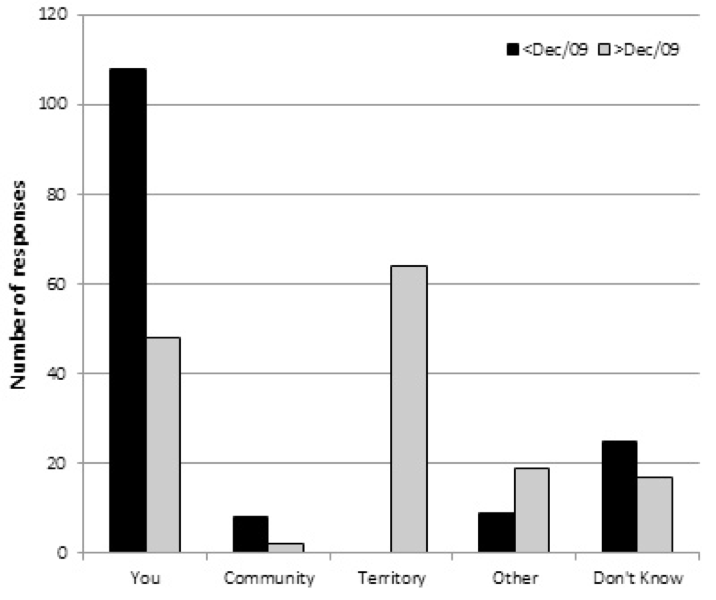

Campers were asked about their sense of decision-making at the household and Camp level before and after the changes implemented under the NTER legislation, as these substantially altered Town Camp governance arrangements (Figures 3 and 4). Figure 11 shows a marked shift from Campers feeling decisions were made at the community or Camp level, to feeling decisions are made by the NT Government. There is also an increase in Campers not knowing who makes decisions. Figure 12 shows a marked shift from Campers feeling they have control and responsibly for their own house, to feeling the NT Government has control; there is also a doubling in the number of Campers who do not know who has control and responsibility. Similarly, Figure 13 shows Campers’ understanding of who makes the household rules, which again shows a perceived shift away from the household to the NT Government.

Figure 9: Importance of cultural obligations |

Figure 10: Source of importance of the Town Camps |

Figure 11: Town Camp decision-making |

Figure 12: Household control and responsibility |

Figure 13: Who makes household rules |

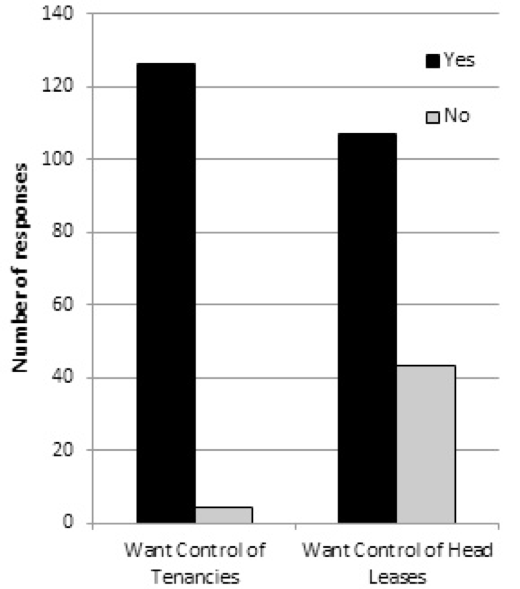

When asked about ongoing control of the Camps, residents overwhelmingly responded that they wish to see this returned to communities (Figure 14). Control over tenancies drew more responses than control over the underlying leases, but both showed the majority of residents in favour of control returning to communities. Quotes from residents on these issues of governance and decision making included:

White man’s rules and laws have made living on Town Camps frightening…we can’t make our own decisions, always white people looking over us.

We don’t have much control of who can move into an empty house. Territory Housing puts anybody in the house, even though we know they are troublemakers.

Territory Housing or Government should not talk on our behalf. We should be the one talking because at the end of the day, we are the one who will be dealing with the issues.

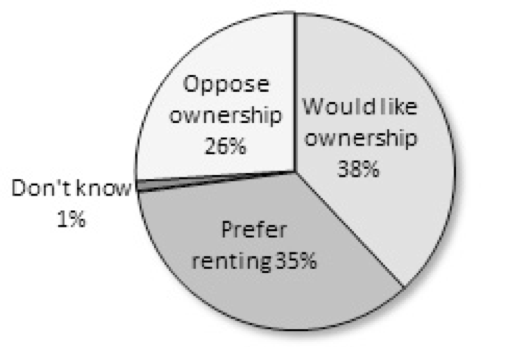

Ownership aspirations

Lastly, Campers were asked about whether they would like to own their homes; Figure 15 shows that 38 percent expressed a desire to own their homes, while 35 percent preferred to rent. Interestingly, 26 percent opposed the idea of owning. Foster et al. (2014, p.23) report that:

Those most opposed to home ownership believe that community land should not be sub-divided nor its purpose changed. This group believes that any move to subdivide land will result in the loss of Town Camp land with the risk that future generations won’t have access to housing or services.

Figure 14: Control of Housing and Town Camps |

Figure 15: Campers’ aspirations for ownership |

In discussing Campers’ responses to questions regarding ownership, Foster et al (2014, p.23) state this is a difficult issue to address, as Campers previously felt they had ownership through the underlying leases and through their housing agreements with each Camp’s Association or Corporation:

Formerly Town Campers had control of their housing through member owned and controlled Housing Associations which ‘owned’ their Special Purpose Leases in Perpetuity (indeed Town Campers understood that the tenancy agreements between their Housing Associations and they themselves as tenants were agreements in perpetuity).’

These subleases were found at law to be periodic tenancies rather than permanent leases, despite not being expressed to be for a fixed period of time and despite the sublease being named ‘Tenancy Agreement Permanent’ as was the case with a Mt Nancy resident and approximately 200 other lease agreements relating to the Alice Springs Town Camps (see Shaw v Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (Shaw) [2009] FCA 1397 at [218], [222], [226]).

However, given Campers have historically felt (and argued) the agreements were perpetual and given that Campers felt forced to sign control over to the government under the Intervention, Campers’ sense of ownership has been challenged. As a result, responses regarding home ownership may be reflecting the above-mentioned desire for control to return to communities as per the underlying leases, rather than a desire for mortgage-backed individual freehold title. This is highlighted in in Foster et al.’s (2014, p.23) observation that:

… respondents saying they would like to own their houses suggested that this was to address their anxiety about being evicted and/or being forced to live under Territory Housing tenancies and laws.

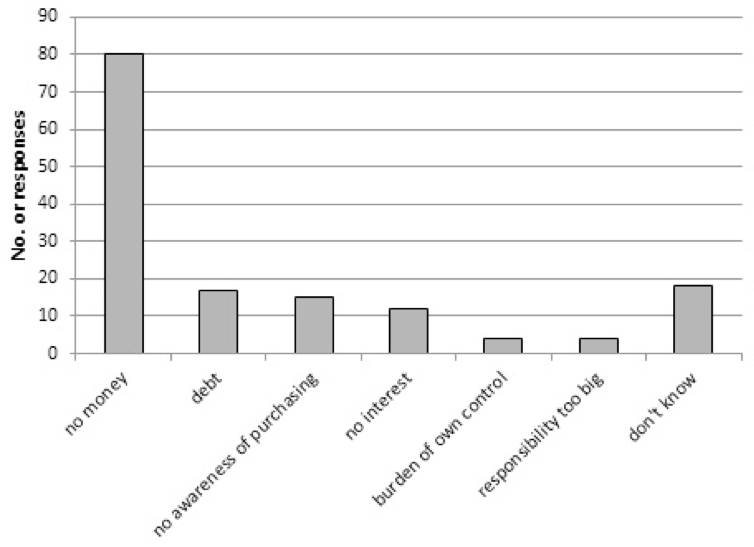

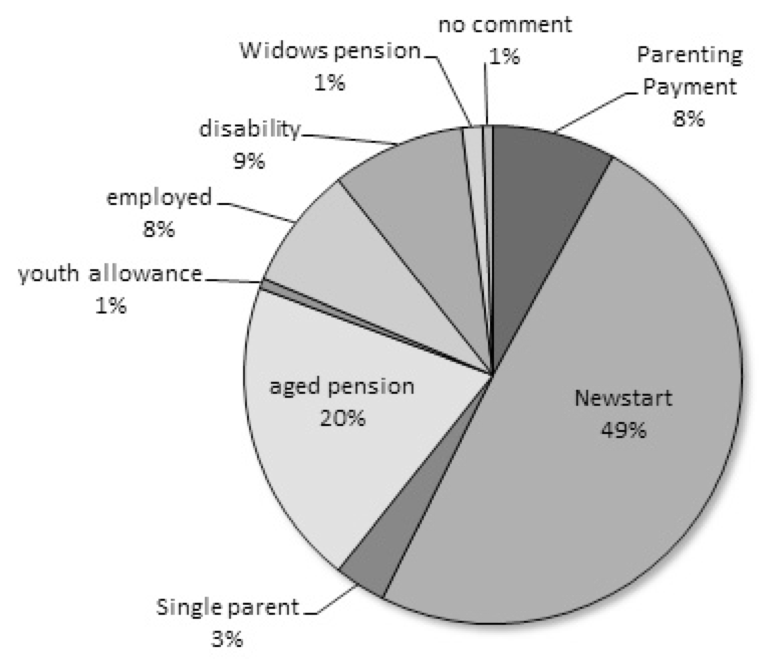

When asked why they had not purchased a house, the majority responded that this was due to their financial situation, whether not having enough money (53 percent) or being in debt (11 percent) (Figure 16). This accords with the majority of households receiving statutory payments as their primary income (Figure 17). Further, when asked about their understanding of owning and renting, the majority of respondents did not understand owning (63 percent), while nearly all (98 percent) understood renting.

Figure 16: Barriers to ownership |

Figure 17: Campers’ main sources of income |

The final report on the joint NT-NSW research identified a framework for appropriate housing models and outlined key attributes of a supportive policy environment; see Figure 18). The research proposed a core set of programmatic features that could be applied to appropriate models of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander housing, reviewed and endorsed by the research partners and the project’s Indigenous Advisory Groups. The features comprised:

- Retention of an interest in the property by a relevant Indigenous organisation. (Here, an Aboriginal Corporation or Town Camp Housing Association).

- Determination and implementation of an appropriate legal agreement according to context and aspirations.

- Inclusion of an upfront price/premium and ongoing administration fee set according to community aspirations, capacity, and objectives.

- Articulation of repairs and maintenance, inheritance, use, etc. in the legal agreement.

- Articulation in the legal agreement of any equity treatment at termination of the agreement.

The report received little fanfare when published, however the authors gave an invited briefing to Federal senior policy advisors at the Territory level. These followed on from repeated briefings at the New South Wales state and Federal government levels at which the team noticed a constant turnover in staff, ongoing lack of sector knowledge, and a persistent assumption that the partner in any equity-based housing models should be government rather than an Aboriginal organisation.

Figure 18: A spectrum of housing options according to key variables

Source: Crabtree et al. (2015, p.6)

Report the second: reviewing service delivery and contractual processes

In 2016 in response to growing concern regarding the timeliness of Camp R&M and the validity Camp tenancy and R&M contracting processes, the Northern Territory Government Legislative Assembly Public Accounts Committee (PAC) called its Inquiry into Housing Repairs and Maintenance on Town Camps. No submissions were positive. According to the Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service’s submission (2016, p.6):

CAALAS has not seen many town camp tenants charged excessively for maintenance, because it appears there is very little maintenance being done … The effectiveness and efficiency of housing services provided to town camps in Alice Springs is confusing and fragmented. By sub-contracting housing services there is a lack of cohesion which not only causes delays and confusion but also inefficiency and a lack of accountability and transparency.

Tangentyere and the lead WSU researcher made submissions to that inquiry, alongside several other Aboriginal community housing providers and service agencies. The inquiry report reproduced the Camp governance diagrams in its assessment of the complexity of arrangements imposed under the NTER, referring to the situation as ‘a service delivery model that was disjointed and unable to provide a seamless service to tenants’ and in contrast to the ad hoc decision to separate tenancy from R&M, stated ‘there may be some benefits to a single provider delivering both property and tenancy management services, particularly in respect to communication and having a thorough understanding of what is happening in both aspects of housing management’ (Public Accounts Committee, 2016, p.34-35).

Later in the year, after a change in Territory government, a review was performed of housing management on all Town Camps across the NT, including the quality of service delivery in the wake of functions being separated and allocated via sub-contracts. Subsequent to the Inquiry and review, the tenancy contract was awarded back to CAAHC and R&M to Tangentyere Constructions, effective July 1. In September 2017, the Northern Territory Auditor-General issued a highly critical assessment of the previous housing contracting system, citing a lack of transparency, unusual pricing, and inadequate assessment of potential conflicts of interest (Walsh, 2017b; 2017c).

Report the third: Enter the consultants

Under Clause 12 of the 40-year subleases, the NT Government is obliged to perform a review of all NT Town Camps every three years. This was raised in the PAC report (Public Accounts Committee, 2016, p.46) and may have been the trigger for a Territory-wide review into all Town Camps that was put out to tender in 2017. The contract was awarded for $2.4m to a private consultant with no track record in working with NT Town Camps. The tender was opened by the incumbent Country Liberal Party and the contract appears to have been awarded while the government was in caretaker mode for the 2016 election, potentially breaching legal requirements. The same minister who had overseen the problematic contractual processes on the Camps that favoured non-community providers, announced the study (Walsh 2017a) through processes that were later found to involve ‘procurement process failures and breaches of policy that no staffer is being held responsible for’ (Walsh 2017c).

The new Labor government released the final report from the work in May 2018. The report runs to over 16,000 pages with no materials in community languages. As per the call for tenders, the report assessed all of the 43 Town Camps in the NT across seven fields: legislation and governance arrangements; leasing and tenure arrangements; housing quality, management and ownership; municipal and essential infrastructure; service delivery arrangements; community aspirations; and, potential economic development opportunities.

The report does not see a future in the existence of Town Camps and refers to supporting the Camps as investing in segregation. Its conclusion is:

We recommend changing the Town Camps model to align with economic realities. To do this we believe in incentivising and enabling Town Camp residents over time to transition to economic centres that are expected to offer a greater diversity and sustainability of employment opportunities (Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, 201, p.10).

In the Alice Springs context at least, this argument is deeply problematic. Campers are already in immediate proximity to an economic centre and many already work in town. Broader systemic issues of unemployment and inequality are unlikely to be resolved by the dissolution of the Camps. Moreover, given the significance Campers attach to their communities and their desire to regain control over the Camps, the potential for such a move to be harmful is substantial. The report concluded that in all, the Camps ranked poor on housing and very poor on legal and legislative, economic opportunity, and governance.

It is worth noting that the assessment of governance in this context is in effect an assessment of the impacts of the complexity of arrangements and entities shown in Figure 3, and the churn of contracts between those entities. However, the report did not discuss that context or the impact of over 10 years of living under the policy, governance, and service delivery framework established and upheld through the NTER, changes to local government, or changes to previous community employment programs (see Jordan, 2016; Altman, 2013). The report’s conclusion was quickly reported and repeated by conservative media outlets (see Aikman, 2018), while the NT Government sought to distance itself from the proposal and reaffirm support for the Camps, attracting criticism from the CLP that had initiated the review and chosen the consultant when formerly in office (Aikman, 2018).

The report outlined problems when undertaking the research but did not expound on how community was engaged or how the purpose of the review was communicated. It must be remembered that many communities are suspicious of government intervention in their lives, and that the consultants were effectively acting as representatives of government:

Our review faced a number of challenges and contradictions, in both the consultation, and the in-community asset assessments… They were happy to have conversations, but once they were told the purpose of the consultation, and what would be done with the information, they withdrew from the process (Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, 2017, p.23).

Regarding the Alice Springs Town Camps, the report assessed the housing as good, economic opportunity and legal and legislative as poor, and in contrast to Tangentyere’s position as a finalist in the Indigenous Governance Awards, the report assessed the Camps’ governance as very poor. Again, it is worth noting that as per Figure 4, the Housing Associations themselves have nothing to govern as responsibility has been removed to the level of the Commonwealth and Territory Government. By not explaining this, the report implies communities are responsible for the governance failure of two levels of government or at best elides that failure, stating that the final step in reform would be to:

… empower Town Camps residents by establishing active representative ownership groups. Once a representative ownership group is formed the group can then work to securing the Town Camp’s space and pursue the development opportunities as decided by the Town Camp’ (Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, 2017, p.160).

That denies the existence of the Associations and Corporations as community organisations already holding title to the Camps, implying analogous entities need to be created (most likely by an external party) to ‘empower’ communities. Regarding extant community power, the report referred to, but did not detail, resistance from Tangentyere regarding elements of the research and stated:

The original methodology was designed to provide an independent, place based, vision for each of the Town Camp communities from information gathered by local Aboriginal people. Tangentyere’s resistance made this more difficult than anticipated, and the modified process has provided a collective vision for Town Camp communities in Alice Springs (Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu 2017, p.148).

Here the importance is placed on the idea of ‘independence’ as requisite and superior (although undefined) with the consultant forced as a result of Tangentyere’s unspecified resistance to present a collective vision that is thus inferred to be inferior, again without explanation. The disjuncture between ‘independent’ and ‘place-based’ and their contrast to ‘a collective vision’ is also jarring; there is no comprehension (or explanation) of Tangentyere as the collective voice of the independent Camps based on their experience and expertise in and of place.

Regarding method, the report refers to the use of Darwin-based community consultants to train individuals in cultural competence and to locals collecting data but does not specify if or how those individuals were recruited, acknowledged, or renumerated for their work. The above quote obliquely refers to, yet glosses over, recent changes to the Camps due to policies oriented towards encouraging the migration of Aboriginal communities into identified ‘growth centres’ at the expense of homelands and outstations, the funding of which remains a political football. Urban Aboriginal communities throughout the NT are experiencing growth as a result of that policy churn, often resulting in community instability as incompatible families come to live in close proximity to each other.

When undertaking research with Tangentyere, the research team behind this paper’s first report found themselves criticised by government for not including such recent arrivals in the survey, despite the fact that such individuals might not have the knowledge or authority to speak to the experience of Camps before the NTER. While the government position was that this was exclusionary, a counter-position is that including newer residents dilutes the community voice and reduces the evidence base for tracking the impact of the NTER and other policy shifts.

That evidence base is built on decades of intimate experience with complex community, service delivery, and policy landscapes and can provide invaluable insight into nuanced and effective policy that reflects community aspirations. A method that can appropriately capture yet distinguish between older and newer community voices has not yet been devised, but given the history of Aboriginal individuals being used (and sometimes paid) by external parties in other jurisdictions to undermine community solidarity (see Treaty Republic, 2011), this is an area that cannot be treated lightly. Further, the NTER itself has been reported as a federal political gambit based on a fictional media portrayal including debunked ‘expert’ non-Aboriginal evidence of child sexual abuse within a community (see Graham, 2017) so transparency and accountability in data gathering and reporting are paramount issues for community.

A rejoinder: ‘Finally We Had Enough’

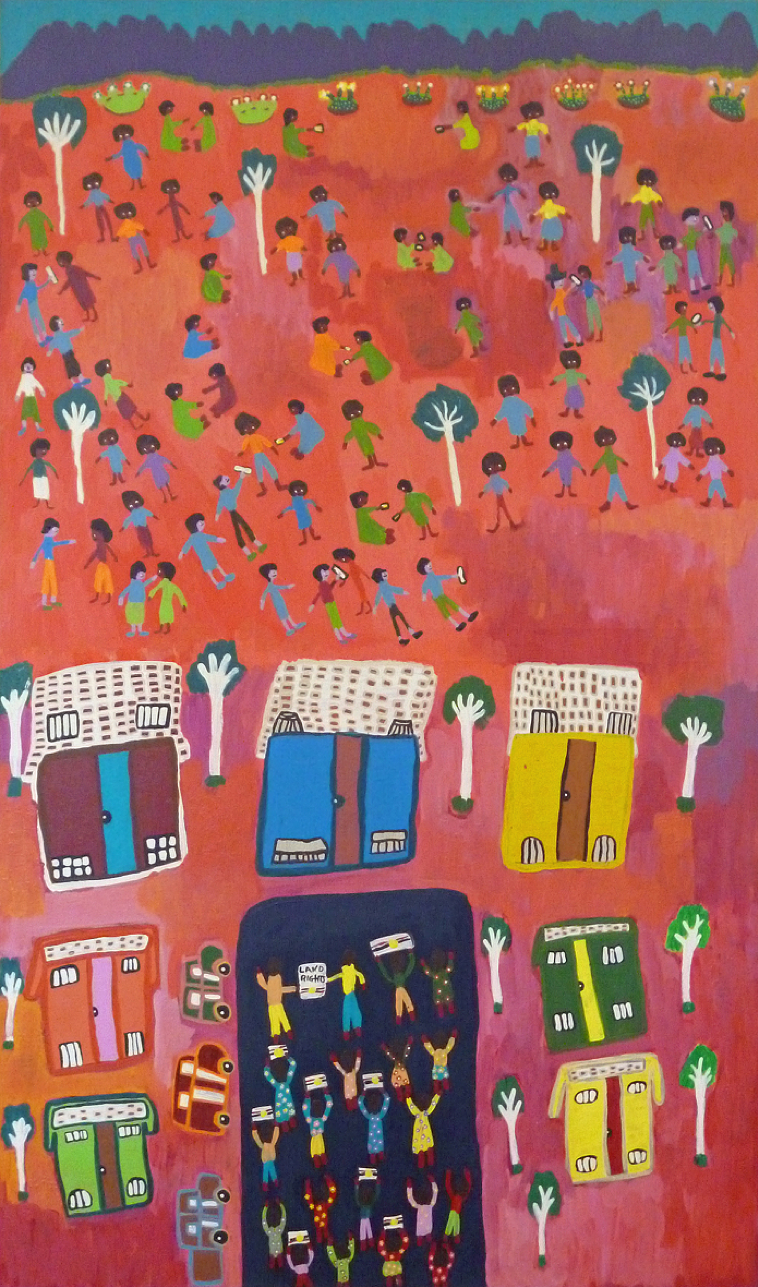

As an example of the evidence base that exists in the knowledge of the Camps, in 2016 a Tangentyere artist (since deceased) documented the local land rights movement and the formation of Tangentyere Council as a fundamental claim to place in the painting ‘Finally We Had Enough’ (Figure 19). The painting’s certificate of authority highlights the Alice Springs Aboriginal community march in 1976 as a core moment in the campaign for land rights and housing on the basis of having lived on the areas that comprise the Town Camps for a long time and with the permission of Traditional Owners.

The painting depicts the protest, with a prominent placard reading ‘Land Rights’. According to the certificate of authority, the right to possess the land had nothing to do with non-Indigenous people and therefore Aboriginal people decided to assert their rights by marching through the streets (McMillan, 2016, p.2). Aboriginal people marched for their land both ‘out bush and in town’ while all ‘the whitefellas locked themselves in their houses’ (McMillan, 2016, p.2).

This stands in stark contrast to the external consultants’ assessment of poor governance and the subsequent recommendation that the Camps warrant closure and dispersal. It also demonstrates that the history of land rights, housing, and community aspirations is a live discussion with its own trajectories and understandings, which ‘mainstream’ policy could do well to pay heed to. In honouring the artist’s passing, their portfolio of over 450 paintings was described as an ‘archive of a visualised oral history of the major social, cultural and economic upheavals in Central Australian desert people’s lives over the past half-century’ (Central Land Council, 2018, p.22).

Figure 19: ‘Finally We Had Enough’ 870 x 1480mm acrylic on linen, 2016

Source: Tangentyere Artists. Copyright: M. Boko and Tangentyere Artists.

Discussion: reports, reports everywhere, and all the evidence did shrink

The Town Camps do not want for reports. Media coverage of the most recent consultant report referred to a sector representative claiming that perhaps 11 reviews of the Town Camps have been undertaken in the previous decade (Aikman, 2017). Research highlights ongoing community frustration at poor housing outcomes and a sense of a persistent lack of traction with policymakers, which is bound up in a sense of a persistent lack of government regard for community input (e.g., Christie & Campbell, 2013; Centre for Appropriate Technology, 2012a; 2012b). Research also highlights a need for nuanced and appropriate responses (e.g., Habibis, 2013; Habibis et al., 2016; Milligan et al., 2011), while government papers and reports maintain a pursuit of home ownership on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lands (e.g., COAG, 2013; FaHCSIA 2010).

While academic research repeatedly highlights diverse community aspirations, policy and public discourse largely focuses on a suite of simplistic, problematic, and universal narratives, namely:

- communities are dysfunctional;

- individuals lack the will or incentive to work; and/or,

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land titling schemes are standing in the way of individual and community progress.

Calls for such reform have largely been made on two premises: firstly, that land reform is crucial as a base for economic and individual development (narratives 2 and 3); and secondly, that land reform is crucial for legal equality and the ‘normalisation’ of tenure and communities (narratives 1 and 2). In 2010, the federal Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2010, p.18) exemplified this discourse, with its first question being:

How can Government achieve the right balance between facilitating home ownership for Indigenous Australians as an economic opportunity and supporting home ownership as a means to help build individual and social responsibility?

However, on the issue of tenure reform and economic development on lands subject to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (the ALRA), Ross (2013) has stated:

… the real impediments to home ownership are not communal title or the Land Councils, but factors that affect most Australians: the cost of houses and the ability of people to pay for them. The key to increasing economic development across Aboriginal lands does not lie in abolishing the customary tenure system; it lies in adapting this system to resolve any specific and genuine problems with the consent of the landowners.

This point is echoed on the Camps, as long-term leases are possible on the underlying leases, subject to the termination of the current subleases back to government. It is possible that appropriate leases for commercial activity could also be developed in this context. The core difference between these options and freehold is the ongoing presence of an underlying Aboriginal entity holding title and the creation of a legal agreement that can enable a backstop mechanism to cure emerging defaults or allow other forms of community intervention to prevent the loss of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander housing and lands. This is an operational matter that could be easily addressed within a sympathetic policy framework focusing on appropriate economic development and community governance.

Moreover, as Ross (2013) asserts, it may be that focusing on tenure reform as an economic development vehicle is back-to-front as, in the absence of appropriate economic development strategies and support, there is no guarantee that the deployment of home ownership models or mortgages within communities will create jobs or businesses. In such absence, the deployment of such models appears problematic and risky. Campers’ lack of access to employment is affected by systemic and structural factors and will not be addressed through land tenure reform. In this context, the conversion of land to freehold and creation of individual lots and personal housing debt presents a real threat of community disintegration, default, foreclosure, and loss of land from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ownership. Earlier work has raised similar concerns; Wensing and Taylor (2011, p.5) state that, based on their review of international studies:

… for Indigenous groups at least, privatisation does not necessarily evolve towards economic efficiency. More commonly, it has led to the dissipation of Indigenous holdings as parcels of land are sold off or lost through foreclosure to non-Indigenous owners.

Further, as both Ross (2013) and this research highlight, there are options that can allow economic development without the abolition of customary tenure. Terrill (2009, p.815-816) asserts that in their push towards land reform on land subject to the ALRA, ‘supporters of township leasing have deliberately misrepresented the arrangements which have previously existed in Aboriginal communities’ and that ‘the real reason that governments prefer township leasing to other leasing models is because of the governance arrangements that it implements.’ He also asserts (2009, p.816, 851) that:

Paradoxically, while proponents of township leasing have drawn support from free market rhetoric, its effect is to introduce a higher level of government control over private decision-making… An alternative is to engage in a more open approach to community leasing negotiations where concerns about governance are acknowledged and a discussion about appropriate governance arrangements forms the basis for developing the most appropriate community leasing model.

These concerns resonate with the Camps and segue to the argument concerning land reform as justified by calls for legal equality. The disconnect between the stated policy position of the necessity of land reform to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economic development, and the actual legal and economic situation of the Camps, resonates with Sanders’ (2010) discussion of the often-competing principles of equality, choice, and guardianship underpinning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs policy. On this, Sanders (2010, p.314) states that:

Legal equality seems simple and fair, but can also be seen as inadequate recognition of the distinctive historical and cultural origins of Indigenous people and of their contemporary disadvantaged socio‑economic circumstances.

In line with Sanders’ assessment, the promotion of legal equality in the Camp context under the rubric of ‘normalisation’ appears to deny the particular history and significance of the underlying Town Camp leases, as well as deny the aspirations and capacity of communities. The most recent consultant report also follows that line and seems ignorant of history and context.

At the first report highlighted, Campers could make misinformed choices when presented with options that individuals and communities have not had time to examine and discuss. Households may express interest in unclarified models of ‘ownership’ if they feel these might reassert prior community governance and/or grant households greater autonomy than the current situation under the subleases to government. This is not surprising, given many felt that the prior arrangements constituted ownership and are frustrated with current arrangements. The promotion of ‘mainstream’ tenure and home ownership currently appears to not recognise the relatively closed nature of Camp housing systems, unless such promotion is operating under the assumption that cultural restrictions on housing allocations will be removed, which may have the appearance (or outcome) of the dismantling of Camp communities.

Similarly, the promotion of socio-economic equality and ‘normalisation’ on the assumption that tenure reform to promote ‘mainstream’ home ownership will drive economic development through the creation of jobs, could also manifest as the erasure of distinctiveness. Such imperatives appear to not be cognisant of structural or social factors that block access to jobs, or of the prior success of locally administered Community Development Employment Programs – the reinvigoration of which might provide more appropriate and successful options.

So, in addition to posing a potential threat to community security, the pursuit of simplistic models of legal equality and ‘normalisation’ in the form of mortgage-backed freehold ownership amongst the Camps has the potential to erase cultural autonomy and distinctiveness. Moreover, the involvement of NT Housing in the Camps as another manifestation of ‘normalisation’ is creating broader perceptions of Camps as public housing, with resultant assumptions as to whether or not residents should be able to stay in their housing if they earn wages.

Historically, the arrangement on the Camps allowed such households to remain in place and pay rents geared to the broader Alice Springs rental sector; this underpinned community stability, created a higher rental income stream, and enabled individual personal and professional development. Reinterpreting or revising Camp housing as ‘normal’ public housing presents a threat to such outcomes, while sub-division into home ownership presents unacceptable risks, and the dissolution of the Camps obliterates communities and their histories. None of these options are desired by community and despite repeated reviews; community aspirations remain deafeningly silent in public and policy discourse.

The existence of such challenges to ‘normalisation’ and simplistic models of equality on the Camps suggests that difference-based policy might be more useful to the identification and establishment of appropriate models and programs. Earlier work has highlighted the relevance of difference-based policy in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander housing space (e.g., Crabtree, 2014; Memmott, 2014) and the results from the community-based survey suggest that the implementation of ‘normalisation’ strategies in the Camp context will act to do ongoing harm to communities by disregarding community aspirations and appropriate governance structures. This presents an opportunity to develop more nuanced policy and programs that can respond to the Camps’ situations and aspirations positively and present models and principles for use elsewhere, including in the broader housing system.

Conclusion

The case of the Alice Springs Town Camps shows that Aboriginal communities remain caught up in an ongoing melee of political opportunism, ideological posturing, dubious contractual dealings, and policy disjuncture, very little of which reflects or respects community experience, knowledge, or aspirations. According to Lea (2012), this is the state operating according to business as usual, creating crises through which it can justify its existence (and perhaps win elections) by responding with prominent flurries of activity. Certainly it is easy to read the situation in this way, with all voices other than those of community being heard (see Watson et al., 2012), unless that voice aligns with prominent political and policy positions of the day or with the intentions of aspirational politicians. Despite the rhetoric of ‘evidence-based policy making’ the reality seems to be much closer to a situation of ‘policy-based evidence making’ in which ideology and discourse create heavy seas for communities, service providers, and others to navigate, often at great individual, community, and public expense.

That said, through submissions to the second report, the community-based research documented in the first part of this paper did manage to influence subsequent contracting processes such that tenancy and R&M returned to community-based service providers. Meanwhile discussions regarding community-based intermediate tenure models on Aboriginal lands are ongoing and growing in multiple jurisdictions (e.g., Yawuru, 2015) and at the time of writing submissions into the consultant report have been called for by the NT Government. Refreshingly, the consultants did not conclude their report by asserting a need for more consultancies, but it does raise the question of how the cycle of political, media, and public churn and outrage might be contained or whether it is more productive to simply circumvent that noise. Some within community are adopting the approach of waiting out the current leases, while the hybrid models under examination and the illustration of incremental outcomes through persistence suggest that opportunistic paths to better outcomes may be the only ones.

Notes

Acknowledgements

The authors give their sincere thanks to AHURI for funding the research underpinning the first report, Isabelle Waters at TCRH for facilitating finalisation of this article, and the staff at Tangentyere Artists for securing permission to use and reproduce ‘Finally We Had Enough,’ copyright for which remains with the late artist. The authors deeply thank the late artist’s family for granting that permission and pay their deepest respects to the family.

References

Aikman, A. (2017, January 6). Study cost more than repairs to housing, The Australian.

Altman, J. (2013). Arguing the Intervention, Journal of Indigenous Policy, 14, 1-151.

Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service (2016) Submission from the Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service Inc. to the Public Accounts Committee, Legislative Assembly of the NT Response to the Inquiry into Housing Repairs and Maintenance on Town Camps, Alice Springs, Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service. https://parliament.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/362490/Submission_No_10_Central_Australian_Aboriginal_Legal_Aid_Service.pdf.

Central Land Council. (2018). Telling stories and painting life, brightly, Land Rights New Central Australia 8(1), 22.

Centre for Appropriate Technology. (2012a). Post Occupancy Evaluation of Alice Springs Town Camp Housing 2008 – 2011. Stage 2.1 Report. Centre for Appropriate Technology, Alice Springs.

Centre for Appropriate Technology. (2012b). Post Occupancy Evaluation of Alice Springs Town Camp Housing 2008-2011 Stage One Report. Centre for Appropriate Technology, Alice Springs.

Christie, M., & Campbell, M. (2013). More Than a Roof Overhead: Consultations for Better Housing Outcomes. Darwin: The Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University.

COAG Select Council on Housing and Homelessness. (2013). Indigenous Home Ownership Issues Paper.

COAG Reform Council (2011) National Affordable Housing Agreement: Performance report for 2009–10, Sydney, COAG Reform Council.

Crabtree, L. (2016a). Exploring hybridity in housing: Lessons for appropriate tenure choices and policy. In W. Sanders (Ed.), Engaging Indigenous Economy: Debating Diverse Approaches (pp. 223–238). Canberra: ANU Press.

Crabtree, L. (2016b) Submission to Public Accounts Committee, Sydney: Western Sydney University. https://parliament.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/362488/Submission_No_8_Western_Sydney_University.pdf.

Crabtree, L. (2014). Community land trusts and Indigenous housing in Australia: Beyond mainstream home ownership, Housing Studies, 29(6), 743–759.

Crabtree, L., Blunden, H., Milligan, V., Phibbs, P. and Sappideen, C. (2012a). Community Land Trusts and Indigenous Housing Options. Final Report no. 185, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Crabtree, L., Moore, N., Phibbs, P., Blunden, H. & Sappideen, C. (2015). Community Land Trusts and Indigenous Communities – from Strategies to Outcomes. Final Report no. 239. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Crabtree, L., Phibbs, P., Milligan, V. and Blunden, H. (2012b). Principles and Practices of an Affordable Housing Community Land Trust Model. Research Report, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Dalrymple, D. (2007). The abnormalisation of land tenure. In J. Altman and M. Hinkson (Eds.) Coercive Reconciliation: Stabilise, Normalise, Exit Aboriginal Australia. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research.

De Soto, H. (2001). The mystery of capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else, New York: Basic Books.

Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (2017). Living on the edge: Northern Territory Town Camps Review, Darwin: Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu.

FaHCSIA (n.d.) Indigenous Home Ownership Issues Paper, Canberra: Australian Government.

Foster, D., Davis, V. and McCormack, A. (2014). Community Land Trusts and Indigenous Communities: from Strategies to Outcomes. Research report, Alice Springs: Tangentyere Council Research Hub.

Foster, D., Mitchell, J., Ulrik, J. and Williams, R. (2005). Population and Mobility in the Town Camps of Alice Springs, Alice Springs: Tangentyere Council Research Hub and Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre.

Foster, D., Williams, R., Campbell, D., Davis, V. and Pepperill, L. (2006). ‘Researching ourselves back to life’: New ways of conducting Aboriginal alcohol research, Drug and Alcohol Review, 25(3), 213–217.

Graham, C. (2017, January 23). Bad Aunty: 10 years on, how ABC Lateline sparked the racist NT Intervention. New Matilda, https://newmatilda.com/2017/06/23/bad-aunty-seven-years-how-abc-lateline-sparked-racist-nt-intervention/.

Habibis, D. (2013). Australian Housing Policy, Misrecognition and Indigenous Population Mobility. Housing Studies, 28(5), 764–781.

Habibis, D., Phillips, R., Spinney, A., Phibbs, P. and Churchill, B. (2016), Identifying effective arrangements for tenancy management service delivery on remote Indigenous communities. Final Report No. 271, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Jordan, K. (2016). Better than Welfare? Work and Livelihoods for Indigenous Australians after CDEP. Research Monograph No. 36. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research.

Lea, T. (2012). When looking for anarchy, look to the state: Fantasies of regulation in forcing disorder within the Australian Indigenous estate. Critique of Anthropology, 32(2), 109–124.

McDonald, S. (2013). New ways to facilitate housing development and ownership III. The shared ownership model. In Cagamas Holdings (Eds.) Housing the Nation: Policies, Issues and Prospects, Kuala Lumpur: Cagamas Holdings Berhad.

McMillan, R. (2016). Indigenous Art Code Certificate: ‘Finally We Had Enough’. Alice Springs: Tangentyere Artists.

Memmott, P. (2014). Inside the remote-area Aboriginal house. In D. Smith, M. Lommerse and P. Metcalfe (Eds.) Perspectives on Social Sustainability and Interior Architecture. Singapore: Springer.

Memmott, P., Moran, M., Birdsall-Jones, C., Fantin, S., Kreutz, A., Godwin, J., Burgess, A., Thomson L. and Sheppard L. (2009). Indigenous Home-Ownership on Communal Title Lands, Final Report 139, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Milligan, V., Phillips, R., Liu, E., Memmott, P., Easthope, H., Liu, E., & Memmott, P. (2011). Urban social housing for Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders: respecting culture and adapting services. Final Report No. 172. Melbourne.

Moran, M., Mcqueen, K. and Szava, A. (2010) Perceptions of home ownership among Indigenous home owners, Urban Policy and Research, 28(3), 311–325.

Ross, D. (2013, February 11). Communal title no obstacle for Aboriginal home ownership. Land Rights News, Alice Springs: Central Land Council.

Sanders, W. (2008a). Is homeownership the answer? Housing tenure and Indigenous Australians in remote (and settled) areas, Housing Studies, 23(3),443–460.

Sanders, W. (2008b). Equality and Difference Arguments in Australian Indigenous Affairs: Examples from Income Support and Housing. CAEPR Working Paper No. 38/2008. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research.

Sanders, W. (2010). Ideology, evidence and competing principles in Australian Indigenous affairs: from Brough to Rudd via Pearson and the NTER, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 45(3), 307–331.

Tangentyere Council (2016). Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory Public Accounts Committee Inquiry into Housing Repairs and Maintenance on Town Camps, Alice Springs: Tangentyere Council. Available from https://parliament.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/362491/Submission_No_11_Tangentyere_Council_Aboriginal_Corporation.PDF.

Terrill, L. (2010). The days of the failed collective: communal ownership, individual ownership and township leasing in Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, University of New South Wales Law Journal, 32(3), 814-851.

Temkin, K.M., Theodos, B. and Price, D. (2013). Sharing equity with future generations: An evaluation of long-term affordable homeownership programs in the USA, Housing Studies, 28(4), 553–578.

Theodos, B., Daniels, R., Pitingolo, R., Braga, B., Latham, S. and Stacy, C. (2017). Affordable Homeownership: An Evaluation of Shared Equity Programs, Washington: Urban Institute.

Treaty Republic (2011). Fortescue Metals Group: Divide, Rule & Bully Tactics https://treatyrepublic.net/content/fortescue-metals-group-divide-rule-bully-tactics.

Walsh, C. (2017a, January 4). Former housing minister Bess Price takes job with company she awarded contacts to, NT News.

Walsh, C. (2017b, September 6). Flawed procurement processes in Housing’, NT News.

Walsh, C. (2017c, May 20). Secret report now released, NT News.

Watson, N., Vivian, A., Longman, C., Priest, T., Santolo, D., Gibson, P., Behrendt, L. and Cox, E. (2012). Listening but not Hearing: A response to the NTER Stronger Futures Consultations June to August 2011. Sydney: Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, University of Technology Sydney.

Wensing, E. and Taylor, J. (2012). Secure tenure for home ownership and economic development on land subject to Native Title. AIATSIS Research Discussion Paper No. 31. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Wensing, E. and Taylor, J. (2011). Home ownership on Indigenous land: whose dream and whose nightmare? AIATSIS Research Seminar paper, Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Whitehead, C. and Monk, S. (2011). Affordable home ownership after the crisis: England as a demonstration project, International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 4(4), 326–340.

Yawuru (2015). Yawuru Home Ownership Shared Equity Scheme. Available from http://property.yawuru.com/yawuru-home-ownership-shared-equity-scheme/

About the authors

Dr Louise Crabtree is Senior Research Fellow and Director of Engagement in the Institute for Culture and Society at Western Sydney University. Her work focuses on community-based, affordable, and sustainable housing options, and appropriate community research practices and protocols. Her work is driving the adaptation and adoption of community land trust principles in Australia.

Email: l.crabtree@westernsydney.edu.au

Vanessa Davis is a researcher at the Tangentyere Council Research Hub. She is an advocate for working in partnership with over 14 years of experience in social research work, evaluation and data input, and analysis. Vanessa has the language, cultural knowledge, and expertise to conduct respectful and in-depth research in Aboriginal communities, and works to sensitise other researchers to the importance of doing things the right way with Aboriginal people.

Email: vanessa.davis@tangentyere.org.au

Denise Foster is a Tangentyere Council researcher who has lived and worked with town camp residents for many years, undertaking many different roles and responsibilities. It was her dream to see her people conduct sound research, giving the people being studied the opportunity to design the research, collect and analyse the data, and return the information to those who gave their time and part of themselves to help make the lives of the town camper better. She succeeded.

Email: denise.foster@tangentyere.org.au

Michael Klerck is Tangentyere Council’s Social Policy and Research Manager and oversees a diverse portfolio of responsibilities. Michael has extensive areas of professional interest, including the impacts on the health and wellbeing of groups experiencing multidimensional disadvantage of: social determinants such as housing, addictions, social and financial exclusion; stress (such as cultural and minority stress); and, poverty.