The capacity to aspire and the Ngukurr News: Exploring the economic potential of a community newspaper

Julie Hall

University of Wollongong

Kate Senior

University of Wollongong

Daphne Daniels

Ngukurr community, Australia

Abstract

This paper explores the role and aspirations of a community newspaper, The Ngukurr News, a publication that has assumed an important role in enlarging the possibilities open to the Ngukurr community in a remote community in Arnhem Land and supporting steps towards economic development and independence. The Ngukurr News stands out as a different kind of enterprise, one that demonstrates how a small community newspaper can act as a mechanism to practice new capabilities and explore new possibilities, building momentum and confidence in a remote Aboriginal community to activate change. As such the experience of The Ngukurr News provides a frame for considering the role of an Indigenous print media enterprise in developing local aspirations and extending the opportunities available to people in remote communities in terms of their economic engagement.

Introduction

Community newspapers can be important tools for empowerment and community development and giving voice to people who might otherwise be ignored, but does their small-scale nature effectively limit their potential to create opportunities for economic development? This paper will explore the role and aspirations of a community newspaper, The Ngukurr News, in a remote community in Arnhem Land. We will argue that the community newspaper, which aims to describe and celebrate local achievement and question the impacts of various decisions regarding the community can play an important role in mobilising community interest, and that this can form the key to enlarging community aspirations. In a communitywhich is almost entirely dependent on government payments, the newspaper demonstrates a step towards independence.

Sharing information in Ngukurr

The Ngukurr community is located in south east Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, 750 kilometres from Darwin. It is home to a population of 900 Indigenous people and a small and fluctuating group of non-Indigenous service providers. Ngukurr’s remoteness is amplified by the dirt road access and the river crossings which are often flooded in the wet season.

The community began as a Christian Missionary Society Mission in 1908, bringing together people from the various tribal groups in the areas, who were seen to be at risk from an encroaching pastoral industry (Cole, 1985). The Mission aimed to convert people to Christianity and bring them together as a community living a settled life, but this was achieved at the cost of the missionaries regulating almost every aspect of everyday life, from the state of houses to the cleanliness of children (Senior, 2003, p.23). By the 1970s, as the Mission withdrew from the community, Ngukurr residents were supported to be more actively involved in community decision making and the sharing of information, and during this period the whole of community meeting became a regular event (Bern, 1977, p.103). As the minutes from a Ngukurr Town meeting of 20 July 1977 report, the aim of these meetings was to discuss ‘council bisiness (sic) with everyone out in the open, blakbalawei and not in small council meetings which people don’t know about’ (quoted in the The Ngukurr News, November 12, 2000).

A report about Ngukurr published in the Black News Service announced the introduction of a new newspaper, the Ngukurr Nyus, which was to be printed in Ngukurr every three weeks. (The Ngukurr News November 12, 2000). It is unclear however, if this enterprise ever eventuated. By the late 1990s the community meetings had become less frequent, although extraordinary meetings were sometimes held to discuss urgent issues, such as the sense of crisis around the numbers of youth involved in sniffing petrol in 1999 (Senior & Chenhall, 2007).

In 2008, governance of the community was centralised to the Roper Gulf Shire, administered from Katherine. This meant that much of the service delivery and welfare-based work in the community was now administered from Katherine and non-Aboriginal workers have positions of authority within various programs. Sanders (2013) describes how centralised ‘super shire’ governance constrains the capacity of local-elected community members to directly influence decision making for their own communities, undermining self-determination and localism in remote Aboriginal communities. The impact has been described by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Mick Good as generating ‘a stronger feeling of disempowerment than the Federal intervention’ (Horn, 2012).

From the Mission times to the present regional shire, the Ngukurr community has experienced a range of different governance structures. What is characteristic of their experience however is a continuing dependence on an outside authority to provide funding for most of the programs and services.

The Ngukurr economy

Ngukurr is characteristic of other Indigenous communities in that it is remote from mainstream work opportunities and employment in the mainstream workforce is low. In 2000, the Ngukurr economy was described in the following way:

Like many, if not all, remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Ngukurr was established primarily as a means of administering Aboriginal welfare policies. It required no modern economic base, nor has it subsequently acquired on, at least not in a manner that is sustainable beyond the provisions of the welfare state (Taylor, Bern & Senior, 2000, p.32).

At this time, the major employer in the community was the federally-funded Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP). Under the CDEP scheme money, equivalent to participant’s unemployment benefits was provided to communities as a block grant (Altman, 2007). As a result, people received an income from participation in a range of activities, including community maintenance and cultural activities, but the scheme also supported a range of small business enterprises including a fish farm, a laundromat and tyre bay (Taylor, Bern & Senior 2000, p.43). Although the economy was limited, the CDEP program gave people an opportunity to think about developing enterprises in the community.

In 2007, the CDEP program was abolished in the Northern Territory as part of the Federal Government’s Emergency Intervention, to be replaced with ‘real jobs, training and mainstream employment opportunities’ (Australian Government, 2007). This move was described by John Altman from the Centre for Aboriginal economic policy research in the following way:

This ranks in my mind as the single most destructive decision in Indigenous affairs policy that I have witnessed in 30 years of research (Altman, 2007, p.1)

The combination of the retraction of the CDEP scheme and the new models of governance have served to further restrict the economic base in the community, at the same time as bringing a model of service delivery, whereby programs are administered externally. There are few opportunities for Indigenous entrepreneurs and very few examples of successful independent businesses.

The role of community newspapers

Much academic writing has focused on the role of community newspapers in marginalised communities such as Novek’s description of the development of newspapers with African American high school students (1995) and inmates of a woman’s prison (2006). A key principal underpinning this approach is an attempt to re-frame the way people in such groups are portrayed by the media:

Communication is also a vehicle by which individuals or groups can change the conceptual frame in which they see themselves, it helps people to form affinities and self-concepts that enable them to take more active roles in their own lives (Novek, 1995, p.72).

Community newspapers can also be a powerful tool in the development of educational skills, by ensuring that they are used for practical purposes. The newspaper, as Hefner (1988) has argued, provides opportunities for the development and fostering of a very wide number of skills:

Many characteristics that most good youth programs share are essential to producing a newspaper: a newspaper is a tangible product that garners public recognition, producing it requires a wide range of talents (everything from licking stamps to investigative reporting) which means that it attracts a diverse group of youngsters; and its periodicity encourages reflection and self-criticism so that one can improve from month to month.

Similarly, Novek writes that newspapers can be a powerful self-determination skill. In her analysis of the outcomes of a newspaper run by African American students, she was able to measure change in four key areas of student attainment:

- The growth of group and individual relationships;

- The crossing of perceived social boundaries

- Experiences and perceptions of enhanced self-efficacy; and

- The development of communicative skills (Novek 1995, p. 76).

All of the above skills, which include affirming a positive view of one’s self and one’s community, as well as the concrete work experience skills provide very positive steps towards the development of the skills to be involved in local entrepreneurship or business development. As such they may be seen as steps towards increasing the range of options individuals have in terms of jobs or businesses they are interested in being engaged with and feel they have the skills to aspire to.

Indigenous Print Media: Redundant resource or under-utilised opportunity?

There is a long history of Indigenous print media in Australia. In 1979, Langton and Kirkpatrick put the spotlight on Aboriginal newspapers, journals and newsletters listing seventy-nine that had been published by Aboriginal and Islander groups, with the first regular publication, The Aboriginal or Flinders Island Chronicle, emerging in 1836 (Langton & Kirkpatrick, 1979). A more recent update by Burrows (2010) notes that more than 20 Indigenous newspapers were published between 1965 and 1989 in Australia. As Meadows (2001) notes, Indigenous groups have long resorted to developing their own media production to challenge and subvert the pervasively negative representation of Aboriginal people in the Australian mainstream media, and as a critical space to express views on social and political issues of importance.

The relevance of newspaper formats as a media vehicle for Indigenous peoples has however, been subject to some critique. As tools of written expression, newspapers have been considered to represent limited value for Indigenous peoples living in areas that continue to experience low levels of literacy (Langton & Kirkpatrick 1979; Avison & Meadows 2015). The format has also been challenged as yet another non-Indigenous construct to be imposed on Indigenous settings, one that typically maintains ‘hierarchical work practices and European forms’ (Molnar,1995, p. 171). In addition, amidst an increasingly diverse and fragmented media landscape, print newspapers now compete with broadcast and digital forms of media production that are viewed as natural allies of Indigenous tradition of oral expression (Molnar, 1995; Avison & Meadows, 2015). The vigorous uptake of media forms such as radio, video, and increasingly internet based media by Indigenous groups in the Australian context suggests the cultural resonance of these media forms (Rice et al., 2016). The relative low cost and direct accessibility of digital media formats, has undoubtedly strengthened the appeal of these emergent tools of expression and resistance, particularly for Indigenous youth (Kral, 2010).

However, rather than arriving at a conclusion that print newspapers are a redundant resource for remote Aboriginal peoples, we propose, from the experience of one remote community in South Eastern Arnhem Land, that they can be viewed alternatively, as an under-utilised opportunity. The experience of The Ngukurr News provides a frame for considering the role of an Indigenous print media enterprise in stimulating capabilities, connections and aspirations required for development in remote communities.

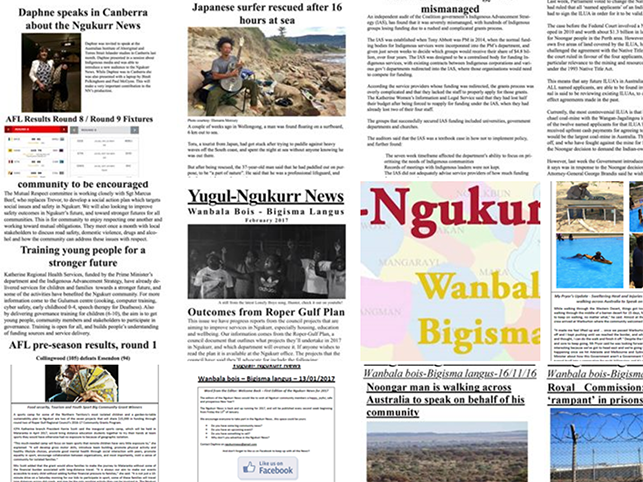

The Ngukurr News

The Ngukurr News was established in 2000 and continued until 2004 (Senior et al., 2017). It was developed as part of an extremely well-funded social impact study of the community (Taylor, Bern & Senior, 2000), which included resources for a full-time project manager resident in the community, salaries for up to six local staff members, a fully equipped office and a vehicle. In 2001, journalist Paul Toohey compiled a feature on The Ngukurr News for The Australian newspaper and commented:

Still in its infancy, probably unaware of its full potential, it may become one of the most significant community based Aboriginal media ventures ever undertaken (15th November 2001).

Despite this promise, The Ngukurr News could not survive a series of structural changes to the community governance, the loss of the building from which it operated and the re-direction of staff to other projects. The value of the newspaper, which was evident to outsiders, was not seen by the local non-Indigenous administrators of the community, who decided to replace it with a council newsletter (Senior et al., 2017).

Following repeated requests by community members, The Ngukurr News, now TheYugul Ngukurr News, was re-established in 2016, with assistance from staff and students at the University of Wollongong (UOW). This collaborative relationship has involved a small number of UOW journalism students undertaking internships to work on The Ngukurr News. In this way, students and Ngukurr community members work together to share knowledge and expertise to produce newspaper content, resembling South African community media models that are sustained by formal partnerships with universities (see Bosch 2003 & Hatcher, 2013). Given the extreme distance between Ngukurr and UOW, most of the co-operative activity in creating news stories actually occurs from afar, with The Ngukurr News community journalists working (remotely) with UOW students to research, edit and finalise news content. This new initiative does not enjoy the same level of financial support as the previous incarnation of the newspaper and the lack of a building from which to operate in Ngukurr, and a vehicle to facilitate news gathering is acutely felt by local staff.

Currently, The Ngukurr News is able to employ three Ngukurr community members on a part-time basis – an editor and two youth journalism trainees – who are assisted by Ngukurr community volunteers. While UOW provides pragmatic support, staff salaries are paid by a combination of short term grants from not-for-profit agencies, meaning stability of paid employment remains a constant challenge.

With a population of 900 people, of which more than half are school-aged children, the newspaper cannot hope to have a particularly wide local readership. However, the creation of a supporting social media page, has, enabled the The Ngukurr News to reach people from neighbouring communities and from across the Northern Territory and Australia.

The Ngukurr community requested that their newspaper be re-established in English language, replicating the previous format. This request, in itself, reflects some desire for development in the community, and the perceived role of the newspaper in facilitating this. For many community members, a newspaper in English is valuable as a literacy tool, promoting English language understanding which can support the management and negotiation of their everyday lives, as well as enhancing broader opportunities. For those without skills to access written English, particularly older community members, The Ngukurr News stories are typically read out aloud by family members, while photographs are discussed amongst the group and cut out for display in homes. It is important to note a recent change, with the inclusion of some news content in Kriol, the local, common language in Ngukurr. This development, however, reflects some broader issues of external influence and decision making in the Ngukurr community, and preferred language content of the newspaper is currently being debated broadly within the community.

The use of The Ngukurr News as a resource which can be passed around and discussed at leisure, perhaps at repeated sittings, appears to fit well with the local way of disseminating information in Ngukurr, through ‘talkin’ story’ (Kariippanon & Senior, 2018). In this way, an issue can be dissected at length and a range of different opinions can be heard. It also reflects some of the pervasive value of community newspapers in the current media melange that stems from their tangible presence (Kitch, 2012), For Kitch, the way that community newspapers disperse physical documentation of local events and issues, can be seen as an act of encircling it’s audience; where they ‘literally circulate, casting a net around a group of people united by personal experience and residence’ (2012 p. 238), The simple process of cutting out stories and images, for display also serves to build permanent documentation of community celebrations and pride (Hatcher, 2012).

Creating opportunities and capacity to aspire

The very important function of Indigenous media in providing paid employment, workplace experience and vocational pathways lacks recognition (Molnar 1995). In remote areas, employment prospects remain scarce, the range of possible jobs is extremely limited and opportunities to gain practical work experience that can extend skills and aspirations are rare. The Ngukurr News journalists, both paid and unpaid, are presented with opportunities to develop skills in identifying, researching, and writing stories, as well as more practical technical skills relating to newspaper layout and production. In the pursuit of news stories, young community journalists navigate a social world that extends way beyond their immediate milieu, interacting with external organisations, and political and bureaucratic figureheads. Improved interpersonal skills, social networking capacity and self-confidence are coaxed from ‘citizen journalists’ in this process (Novek, 1995; Romano, 2010; Senior, Chenhall & Daniels, 2017). The fostering of intersecting networks between young Aboriginal people and figures of power that occurs within this professional sphere, can work to reorient views about young people in remote communities, and assist to build ‘linking’ social capital (Woolcock & Narayan, 2000). For young Aboriginal people from remote areas, value associated with ‘linking’ social capital can be realised through simple acts such as the transfer of information about work or training opportunities from networks of power that would not typically transpire within their own bounded social networks. Amidst the broader socio-cultural context where opportunities for Aboriginal people to build vertical social networks with people and places of power remain limited (Walter, 2015), the practices of young Ngukurr journalists represent a pathway to explore, and expand the spaces of possibility.

For Appadurai (2004), the act of navigating expanded social spaces supports cultivation of ‘the capacity to aspire’; a practice of imagining the future that ‘thrives and survives on practice, repetition, exploration, conjecture and refutation’ (p. 69). For young Ngukurr journalists, the exploration and trialing of new spaces of possibility, allows for ‘alternative futures’ (Appardurai, 2004, p. 69) to be practiced and imagined, and for them to expand the range of things to which they are able to aspire.

Voicing and expanding aspirations

Appadurai’s (2004) attention to the critical relationship between ‘the capacity to aspire’ and the development of a ‘voice’ can also be drawn upon within the frame of a community newspaper. The reciprocal, interwoven, relationship between finding a voice through tools of self-articulation and extending aspirations is well illustrated in the burgeoning local conversation in The Ngukurr News about the development potential of outstations in Ngukurr. Twelve outstations surround the town of Ngukurr, and despite depletion of government funding and support, outstations remain places where small moments of change and resistance are part of people’s imagining of a better future. It is however, increasingly difficult for Elders to imagine a future for their cultural homelands as some properties become uninhabitable due to lack of maintenance. Available funding for outstation maintenance is fragmented, and often difficult to access due to eligibility criteria, and decision-making processes around funding allocation are unclear. As a result, outstation families are caught between their hope for the future of their homelands and the reality of practicalities of everyday life in the community, including the need to access education and the health clinic.

Motivated by increasing community concern about the future of outstations, The Ngukurr News team was prompted to examine the issue of outstation funding and local government decision making around outstation expenditure. As part of this, a Shire Council authority was interviewed to clarify outstation expenditure processes. One specific outstation property near Ngukurr was brought to the spotlight during this interview. This particular property had recently become uninhabitable due to sewerage overflow menacing local houses and creating a public health concern. Sewerage overflow also threatened the vision of traditional owners to develop a camping and cultural tourism site on the property. While publicly available documents indicated a significant amount of Shire Council funding had been allocated to maintenance of this land, it was difficult to identify any beneficial outcomes on the property. The result of the Shire Council interview was a frank admission that public documents had incorrectly portrayed expenditure for this outstation. The interview also garnered a commitment from Council to improve clarity of information and consultation processes with outstation families in the future. The following day, the sewerage problem at the outstation of focus was resolved, as were other key maintenance issues, some of which had been ignored for six years.

The Ngukurr News outstation story that was subsequently published, debated the funding challenges experienced by local outstations, and highlighted the commitment from the Shire Council to improve consultation and clarity around outstation expenditure. Importantly, it also showcased the story of the outstation that had contested and questioned the funding status quo, embedding in the account an alternative vision of outstation development through cultural tourism. An ongoing series of outstations stories are planned for The Ngukurr News, designed to open local conversations about different experiences and hopes, and bolster imaginings of what is possible in the future of outstations, reflecting a process described by Appadurai where ‘local horizons of hope and desire enter a dialogue with other designs for the future’ (2004: 75). For the Ngukurr community, it has been a critical mobilization of ideas and alternative plans for the management and development of outstations at a time when hopes for their future was rapidly dismantling.

Sustainability

The Ngukurr News runs on a miniscule budget and is dependent on one-off philanthropic grants, volunteers and university support. As such it is vulnerable, but it is also resourceful and project participants are continually forced to consider issues of sustainability.

Hatcher (2013) draws attention to issues of sustainability of community newspapers for marginalised groups. In the South African context, he observes core issues that undermine community media ventures, including: weakness of local economies that inhibit advertising revenue, limited business and journalism capacity of residents, and lack of support from local government agencies. Many parallels can be drawn with the context of remote Indigenous communities. In Ngukurr, the fledgling newspaper is not funded or actively supported by government departments and there is no local economic base to generate commercial advertising. In 2017, applications for philanthropic grant funding for Ngukurr staff salaries have been largely unsuccessful, primarily on the basis that remote Indigenous media projects are not an important funding priority, or that the project is too geographically remote or ‘distant’ from funding body sightlines.

In this environment, The Ngukurr News’ editor and staff have become resourceful in exploring options to counter the vulnerability of their newspaper. For a start, an advertising base has been established through appealing to politicians and agencies that serve the Ngukurr community to purchase regular advertising space in The Ngukurr News. In this way, local members of parliament, and health and government service agencies, many of whom are located four hours away in the town of Katherine, are provided with a valuable mechanism to disseminate ‘hyperlocal’ information and messages.

Resourcefulness has also been directed at the collaborative relationship with the University of Wollongong; with realisation by The Ngukurr News’ staff of some broader development potential circling the newspaper activities. In particular, the successful placement of two UOW journalism students in Ngukurr in 2016 and 2017 has opened up some latent community development aspirations. Placed in Ngukurr for a short period, UOW students were primarily tasked with helping with production of The Ngukurr News. However during their visit, Ngukurr Elders engaged the students in an active program of cultural immersion and understanding. Elders were cognizant of the need for non-Indigenous students to develop understanding of Aboriginal lives and culture, particularly journalism students, who in the future will likely contribute to the public representation of their lives. Elders also held a fledgling vision of the possibility of cultural tourism as an economic enterprise in Ngukurr and surrounds, and the visit of the UOW students provided a pathway for exploring and practising this vision.

As a result of the recognised depth and value of these student experiences in Ngukurr, a process to formally embed The Ngukurr News student internships as an accredited UOW ’Reciprocal Learning’ subject has been initiated. It is anticipated that the situated learning experience of living and working in a remote Aboriginal community will be opened up to many more UOW journalism and social science students, generating a modest income stream for the community, some of which can be reinvested in The Ngukurr News and the development of outstations.

Concluding discussion

Hatcher (2013) proposes that ‘hybrid’ media models are commonly adopted by under-resourced communities to secure sustainability and stability of community media outlets. The Ngukurr News’ trajectory depicts a ‘hybrid’ model at work in a remote Aboriginal community with constrained resources to draw upon. The newspaper has employed strategies such as recruiting and training Ngukurr community members to be journalists and has engaged university and community resources to provide this training. A diverse funding base has been sought, including a span of advertising, NGO grants, philanthropic donations, and most notably a supportive collaboration with the University of Wollongong has been developed to underpin and expand the venture, mimicking many of the successful strategies for media sustainability observed by Hatcher in marginalised communities.

The Ngukurr News model draws institutions and Ngukurr community members together which has assisted to sustain the community newspaper, but has also fulfilled another critical role; It has coaxed not only ‘capabilities’ from project participants, but also ‘possibilities’ that are beginning to be observed as realities in some fledgling economic development projects in this remote Aboriginal community. Economic development activities in remote Aboriginal communities have become even more limited with the decline of the art market post the global financial crisis. The Ngukurr News stands out as a different kind of enterprise; one that demonstrates how a small community newspaper can act as a mechanism to practice new capabilities and explore new possibilities, building momentum and confidence in a remote Aboriginal community to activate change. The Ngukurr News is highly regarded by the local community as it brings with it additional benefits such as literacy and leadership, but the value of the News is not necessarily regarded in the same way by outside funding organisations which have formed their own conceptualisations of what interventions carry most benefit to remote Aboriginal communities. The Ngukurr News is a fragile enterprise, but through the activities involved with ‘news making’ and collaboration it holds the potential to develop local aspirations and extend the opportunities available to people in terms of their economic engagement.

References

Altman, J.C. (2007). Neo-paternalism and the destruction of CDEP, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Topical Issue No. 14/2007.

Altman, J. & Gray, M. (2005). The economic and social impacts of the CDEP scheme in remote Australia, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 40(3): 399-410/

Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition In V. Rao, and M. Walton (Eds.) Culture and Public Action. Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press pp.59-84.

Australian Government (2007). CDEP in the Northern Territory Emergency Response Retrieved from https://formerministers.dss.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/cdep_qa_230707.pdf.

Avison, S. and Meadows, M. (2015). Speaking and hearing: Aboriginal newspapers and the public sphere in Canada and Australia Canadian Journal of Communication, 25(3), pp. 1-10.

Bosch, T. (2003) Radio, community and identity in South Africa: A rhizomatic study of Bush Radio in Cape Town. Faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio. Available at: http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=ohiou1079300111 (Accessed: 9 October 2017).

Burrows, E. (2010). Tools of resistance: the roles of two Indigenous newspapers in building an Indigenous public sphere. Australian Journalism Review, 32(2), 33-46.

Hatcher, J.A. (2012). A view from outside: What other social science disciplines can teach us about community journalism, in B. Reader and J. Hatcher (Eds) Foundations of Community Journalism. USA: Sage Publications Inc.

Hatcher, J.A. (2013). Journalism in a complicated place: The role of community journalism in South Africa’, Community Journalism, 2(21), 49-67.

Hefner, K. (1988). The youth involvement model: The evolution of youth empowerment. Social Policy 19:21-24

Horn, A. (2012, 31 January). Super shires condemned as worse than Intervention, ABC News. Available at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-01-31/20120131-mick-gooda-on-super-shires/3802586.

Kariippanon, K. & Senior, K. (2018). Re-thinking knowledge landscapes in the context of grounded Aboriginal theory and online health communication, Croatian Medical Journal 59(1), 33. doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2018.59.

Kitch, C. (2012). Making the Mundane Matter, In J. Hatcher, J. and B. Reader (Eds). Foundations of Community Journalism. USA: SAGE, pp. 237-239.

Kral, I. B. (2010). Plugged in: Remote Australian Indigenous Youth and Digital Culture, Caepr Working Paper, (69), pp. 1-17. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2244615.

Langton, M. & Kirkpatrick, B. (1979). A Listing of Aboriginal Periodicals, Aboriginal History, Vol. 3(19), pp. 120-127.

Meadows, M. (2001). Voices in the Wilderness Images of Australian People in the Australian Media. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Molnar, H. (1995). Indigenous media development in Australia : A product of struggle and opposition’, Cultural Studies, 9:1(October), 169-190.

Novek, E. M. (1995). Buried treasure: The community newspaper as an empowerment strategy for African American high school students’, Howard Journal of Communications, 6(1-2), 69-88. doi:10.1080/10646179509361685.

Novek, E.M. (2006). Heaven, Hell and here: Understanding the impact of incarceration through a prison newspaper, Critical Studies in Media Communications, 22(4): 281-301.

Rice, E. S. et al. (2016). Social media and digital technology use among Indigenous young people in Australia: a literature review, International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 81. doi:10.1186/s12939-016-0366-0.

Romano, A. (2010). Deliberative Journalism. In A.Romano, (Ed.) International Journalism and Democracy: Civic Engagement Models from around the World. Taylor & Francis, pp. 1–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.17730/0888-4552.39.1.44.

Sanders, W. (2013). Losing localism, constraining councillors: Why the Northern Territory supershires are struggling, Policy Studies. 34(4), pp. 474-490. doi:10.1080/01442872.2013.822704.

Senior, K., Chenhall, R. D. & Daniels, D. (2017). ‘No More Secrets – Ngukurr News’: Looking back at the contribution of a community newspaper in a remote Aboriginal setting, Practicing Anthropology, 39(1), 44-48. doi: https://doi.org/10.17730/0888-4552.39.1.44.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Senior, K. (2003). AGudbalaLaif? Health and well-being in a remote Aboriginal community – What are the problems and where lies responsibility? PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

Senior, K. & Chenhall, R. (2008). Walkin’ around at Night: The background to teenage pregnancy in a remote Aboriginal community’ Journal of Youth Studies, 11(3), 269-281.

Senior, K. & Chenhall, R. (2012) Boyfriends, babies and basketball: Present lives and future aspirations of young women in a remote Australian Aboriginal community, Journal of Youth Studies, 15(3), 369-388.

Senior, K., Chenhall, R., & Daniels, D. (2017). ‘No more secrets Ngukurr News’: Looking back to the contribution of a community newspaper in Arnhem Land, Practicing Anthropology (39)1, 44-48.

Taylor, J., Bern J., & Senior K. (2000). Ngukurr at the Millennium: a baseline profile for social impact planning in south east Arnhem Land, CAEPR Research Monograph No 18, Australian National University.

Walter, M. (2015) The vexed link between social capital and social mobility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 50(1), 69-88.

Woolcock, M. & Narayan, D. (2000). Social capital : Implications for development theory , research and policy, The World Bank Research Observer, 15(2), 225-249.

About the authors

Julie Hall works as a project manager at Research for Social Change at the University of Wollongong. She is a PhD candidate studying the development role of collaborations between universities and remote communities in Australia with a focus on The Ngukurr News as an illustrative case study.

Email: juliehal@uow.edu.au

Associate Professor Kate Senior is a medical anthropologist with 20 years of experience working in remote Indigenous communities in Australia to explore people’s understandings of health and well-being and their relationships with their health services. Senior has a particular interest in the health and well-being of Indigenous Adolescents and was awarded an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship in 2012 to explore how young people live and understand the social determinants of health. Previous to this, Kate led a multi-state ARC Linkage project to explore young people’s sexual health and their understanding of risk, vulnerability, and relationships. As part of this project, Senior developed a range of innovative and youth friendly research methods to effectively engage young people in sexual health research.

Email: ksenior@uow.edu.au

Daphne Daniels is a Ngukurr community member. She worked as a researcher on the South East Arnhem Land Collaborative Research project (1999-2004) and became the editor of the Ngukurr News. Daniels has been an advocate for change in her community and has been a member of the Community Government Council as well as the Sunrise Health Community Advisory Council.