Disability income reform and service innovation: Countering racial and regional discrimination

Michelle Fitts

Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University

Karen Soldatic

Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University

Abstract

Since the early 2000s, the Australian Government has initiated a number of reforms across the disability sector which have largely involved procedural changes to the assessment of medical evidence and the eligibility criteria for the Disability Support Pension (DSP). While there are increasing anecdotal reports of these reforms influencing the overall number of claimants being granted the DSP, there is limited understanding of how service providers that support clients applying for the DSP have been affected by these reforms. This research pays particular attention to services working predominantly with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients in a regional North Queensland city, Townsville. The participants were professionals from employment agencies, health, disability and mental health services, community legal services and non-government agencies. Medical and other professionals found the new format and processes for completing medical reports time consuming and requested greater communication from the government regarding changes to DSP legislation. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients experienced several barriers to fulfilling the assessment criteria, including financial costs to access all reasonable medical care and reports. This article illustrates the gap in support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients on Newstart Allowance (general unemployment benefit) awaiting the outcome of their DSP application, even though it is clear from their medical evidence that they are living with high levels of impairment, chronic conditions and disability.

Introduction

The combined effects of the neoliberalisation of regional economic policies and Indigenous social policies of localised economic development are most acutely felt by those who are reliant on mainstream social security payments (Soldatic et al., 2017). This is particularly the case for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who self-identify as living with disability but who do not meet the eligibility threshold for the Disability Support Pension (DSP) due to the ongoing restrictions on the payment (Soldatic, 2019). In Australia, the primary social support payment for working-aged individuals (16-65 years) living with a disability is the DSP. In Australia, approximately 4.2 million Australians are considered to be living with an impairment and/or chronic illness and condition (ABS, 2012a), and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians aged 35 to 54 years are around 2.7 times more likely to have a disability than non-Indigenous persons (ABS, 2012b). ABS estimates suggest that 44 percent of the Australian regional population identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ABS, 2017). Regional centres are becoming increasingly urbanised as smaller towns and communities retract with neo-liberal disinvestment in rural economies and concentration in larger regional centres (Beer, 2012).

Following global trends with the onset of neo-liberal economic restructuring in the late 1980s/early 1990s, the number of people with disability in receipt of the DSP began to outstrip the number of people on the unemployment benefit – Newstart Allowance. The reasons for this are threefold. First, since the early 1990s governments have made persistent efforts to reduce the range of social security payments for administrative ease. Categories such as widow pensions were discontinued and those recipients, largely women, were transferred onto the DSP (Soldatic, 2019). Second, the DSP was unique in that disability was conceptualised broadly to take account of economic restructuring which led to a large group of workers being unable to find appropriate and suitable jobs, and hence were ‘labour market’ disabled (Morris et al., 2015). Finally, reforms to the DSP in the late 1980s occurred within a context of growing neoliberal discourses of labour market activation and were driven by a social security policy that encouraged the participation of people with disabilities in the labour market while recognising the need for flexibility in response to individual impairments (Grover & Soldatic, 2013). Writers such as Morris and colleagues (2015) identified that the DSP often operated both as disability social security payment and, at times, as a way to hide real structural unemployment for those individuals excluded permanently from the labour market with neo-liberal restructuring. Overall, the increase in DSP recipients in the period 1972 to 2004 was approximately 400 percent (Dalton & Ong, 2007), reflecting the ongoing neoliberal restructuring of the Australian economy and the combined effects of labour market and social security law, policy and social programming.

In response, successive Australian governments have introduced a sequence of new policies to restrict eligibility for the DSP, involving: lowering the work capacity threshold to less than 15 hours a week instead of 30 hours as had previously been the case; implementing new assessment procedure which, among other things, effectively institutes a two-year waiting period before becoming eligible for the DSP during which time people living with disability are required to remain on Newstart Allowance and undertake a range of service-directed employment activation strategies such as training and skills development; restricting the impairment tables used in the process of determining an applicant’s eligibility for DSP and removing a number of medical conditions; and using government-contracted doctors to review ‘raw’ medical information as opposed to applicants’ treating doctors supplying medical reports; reassessing existing DSP recipients for eligibility under the proviso that their permanent and ongoing disability may have improved since initial eligibility was granted; and the introduction of a core criterion that requires the individual’s condition to be stable and fully treated for at least two years. Therefore, even severe conditions such as final-stage dialysis or cancer, do not necessarily qualify for DSP eligibility as these medical conditions and illnesses are considered treatable and unstable, even though the instability of the condition is associated with significant decline or even death (see Neale, 2016; Soldatic, 2018b).

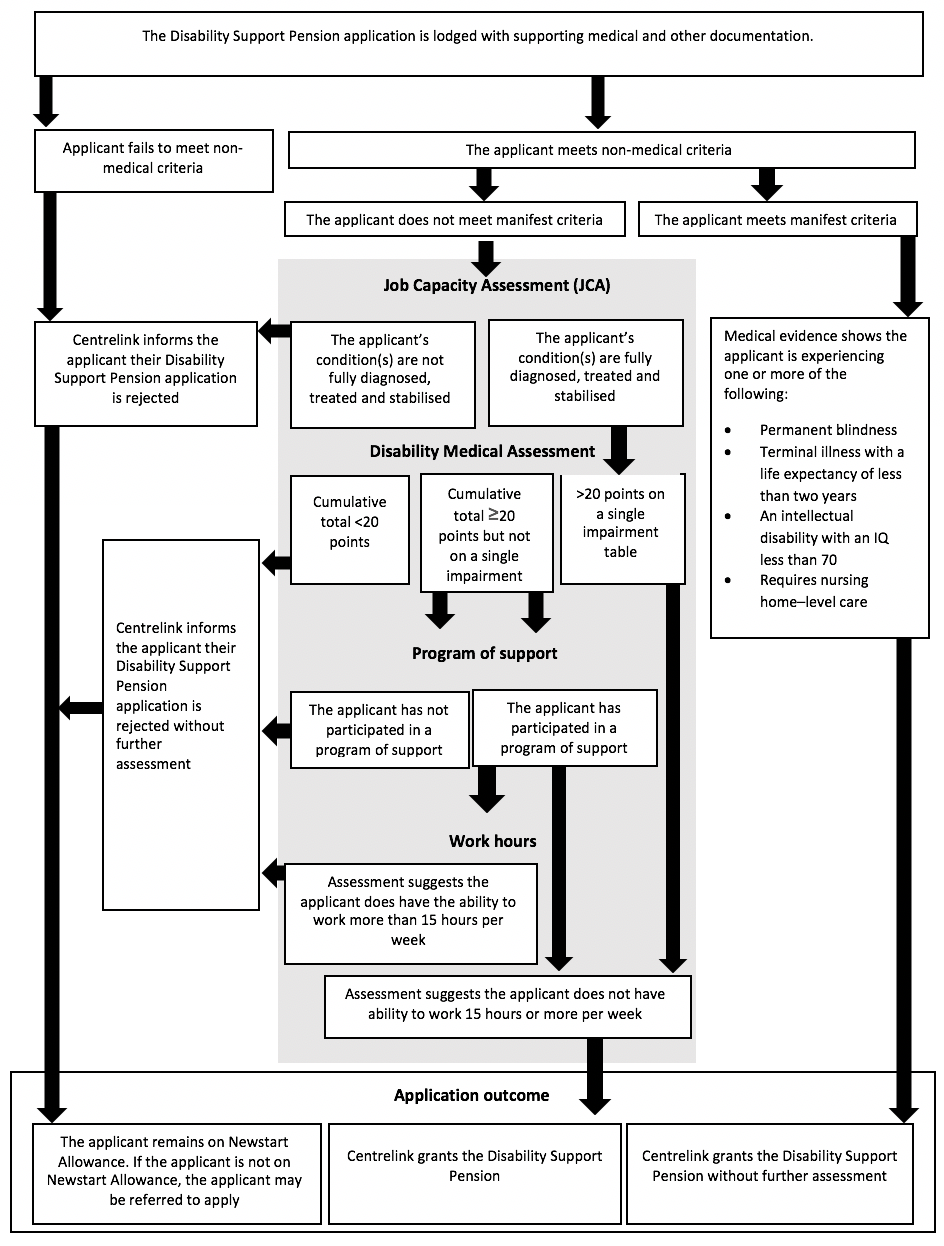

Reforms implemented in 2015 were the latest in this landscape of continuing eligibility retraction and restriction. From 1 July 2015, medical reports from treating doctors were no longer required for any DSP claims (Australian Government, 2018b). Instead, new applicants are now given a checklist of types of primary medical evidence that they wish to supply to support their application. The review process of this evidence has also changed. As illustrated in Figure 1, new applicants are now required to fulfil a two-stage DSP application assessment process. Applicants are required to undertake a Job Capacity Assessment conducted by an allied health professional such as an occupational therapist, psychologist or social worker. The aim is to identify a person’s level of permanent functional impairment resulting from permanent medical condition(s) and to assess a person’s ability to work based on the medical condition (Australian National Audit Office, 2016). If a job capacity assessor deems the condition to be fully diagnosed, treated and stabilised, the impairment is rated using the points system in the impairment tables. Assessors are required to take into account all potential work opportunities in the open labour market in Australia and not just those at the location of the applicant (Australian Government, 2018a). If the job capacity assessor concludes the applicant meets the DSP criteria, they move into what is known as the Disability Medical Assessment. During this process, a government-contracted doctor reviews the medical evidence provided by the individual in support of their DSP application to verify whether the evidence demonstrates: 1) the medical condition(s) are permanent for the purpose of the DSP qualification, and 2) the level of functional impairment resulting from any permanent medical conditions. As shown in Figure 1, individuals with an impairment that equates to 20 points or more but not on a single impairment table are required to participate in a program of support. The program of support is intended to help people with disability prepare for and secure a job (Department of Human Services, 2018b).

Figure 1. Disability Support Pension claim assessment process

The effects of these combined changes are particularly racialised and spatialised (Soldatic, 2018a,b, 2019). It is often Aboriginal Australians living outside Australia’s large urban cities, such as Sydney or Perth, who are most adversely affected by these reforms. Soldatic’s work (2018a,b, 2019) confirms the findings of the public reports of the Australian Government’s Ombudsman Office (Neave, 2016) which show that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians living with disability are acutely disadvantaged within the DSP assessment process, and that this disadvantaged is further shaped by living in a regional area where there are few intensive, affordable and accessible procedures and/or interventions that would ensure the substantive body of medical evidence required for determination assessment.

The denial of the DSP and the granting of Newstart Allowance suggests that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons living with disability are therefore likely to be caught in the mainstream welfare to work programs, such as the revamped Community Development Program in rural areas. The Newstart Allowance and Community Development Program (CDP) have stringent levels of welfare conditionality – requirements that participants must meet in exchange for welfare payments – together with punitive policing of recipients’ continual attendance (Soldatic, 2019). As a result of all these authoritarian restrictive measures, it well documented within the research that the CDP now has the highest level of ‘breaching’ of all Australian income support programs (Jordan, 2018). Individuals can be breached for a multiplicity of reasons. In the third instance, the individual will lose part of their fortnightly social security payment or can lose their payments for up to eight weeks. Jordan’s (2018) research indicates the significant consequences much more broadly on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons and their communities that are subject to these activation welfare-to-work strategies. Australian Governments’ bi-partisan support for the neoliberalisation of Indigenous and disability welfare and labour market restructuring stands in contradistinction to its ‘close the gap campaign’ on Indigenous health, disability and socio-economic inequality. As identified in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the ILO C169, the Indigenous and Tribal Persons Convention (articles 24 and 25 – Social Protection and Health), non-discriminatory access to appropriate and adequately resourced social security systems is the critical platform for realising Indigenous wellbeing, participation and material equality.

Yet, despite the growing body of evidence that clearly indicates the failings of the neoliberalisation of social security and labour market policy, Australian Governments persist in expanding the policy normalisation of these very forms of governance. Moreover, there is little substantive knowledge about the services on the ground in regional Australia working to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in their claims for entry to the DSP. As noted, with the onset of neoliberalisation, governments have not only withdrawn from direct delivery of social services but, in fact have also increased their disciplinary regimes through extensive, complex contractual systems of governance with not-for-profit and for-profit providers (Marston et al 2016). Service providers in this area are required to work within the confines of their contractual parameters while simultaneously advocating on behalf of their clients. Some of the worst excesses of neo-liberal restructuring to the not-for-profit sector and the privatisation of government welfare delivery in Australia have seen contractual arrangements thwarting such services’ advocacy for policy reform and for their clients (see Marston et al 2016). It is this element of disability social security reform and the severe constraints under which regional not-for-profit and community legal services operate that we seek to explore, particularly their responses to their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients living with disability who do not qualify for the DSP.

Indigeneity, Regionality and Disability Income Reform

The research interviews drawn on in this paper with professional service providers and community legal centres are part of a large, national three-year study that aims to examine the ways in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians living with disabilities, their families and communities experience, and respond to, the challenges imposed by national disability income reform and rapid regional economic restructuring occurring in large Australian regional towns and centres (ARC DE160100478). Previous research by Pini and colleagues (ARC DP 110102719) identified that rural restructuring has significant implications for the social, cultural and material wellbeing of people with disabilities living in rural landscapes (see Soldatic et al., 2017; Soldatic, 2018a, b). Yet there has been a dearth of research on regional urban economic development for people living with disability, and no work could be identified for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians living with disability in regional centres. This was curious given it is well established that with neo-liberal disinvestment in rural areas, there has been a general trend towards the centralisation of rural services into regional centres across all Australian states (Beer, 2012). Longstanding work on regionality and economic development such as that of Beer (2012) has identified the criticality of Australia’s social security system to regional economic development and social sustainability, and often to mitigate the worst excesses of neoliberal economic restructuring of regional economies. Researcher’s such as Jordan (2018) have argued that there is a need for new institutional arrangements to recognize and realise the rights of Indigenous Australians with the significant changes that have emerged across these landscapes.

These combined elements suggest that regional urban centres are particularly important for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disability. Rapid ongoing regional urbanisation involves greater concentration of specialist services, hospitals and, often, labour market opportunities. Social security activation strategies increasingly place pressure on highly marginalised welfare recipients to move to areas where it is assumed, within neo-liberal labour market strategy, that employment is more likely to be achieved. Further analysis supported these initial reflections. In reviewing disability service usage across Australia, it appeared that regional centres were significant for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disability for a number of additional reasons. Access to services and to health and disability professionals was significant. In addition, regional centres offer a mid-way point that enables ongoing connection to family, kin and country while maintaining timely and responsive service usage and support. The concentration of disability and health services in regional centres alleviates the need for expensive long-distance travel to state capitals, such as Perth, Brisbane or Sydney, where there are often no family or cultural supports of significance. Remaining near family and country facilitates healing, wellbeing and cultural connection through enabling visits with core members of one’s cultural group. All these factors combined suggested that living with a disability in a regional centre has particular implications for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their broader familial and kinship networks.

While the national study investigates the experiences of DSP restructuring on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disability, their families, kin and support networks, the aim of this article is to identify, document and articulate: 1) the experiences of and impact on service providers following the 2015 legislative reforms to the DSP eligibility threshold; and 2) how service providers who are involved in facilitating access for Indigenous people living with disability to the necessary evidence, reports and information for DSP eligibility assessment have responded to these changes.

Setting: Townsville and beyond

Townsville is a provincial city located in tropical North Queensland which has undergone extensive, and often rapid, change in the last 20 years. It is situated on Ross River and was established as the major port for the cattle industry for the region. Since the 1990s it has also been the primary city for fly-in/fly-out (FIFO) workers for the mining industry and has experienced significant demographic changes linked to this sector. In the 2016 census, Townsville had a population of 229,031 (50.1% men) yet it is estimated that, with the closure of the surrounding mines and mining disinvestment, the population has dropped significantly as FIFO mine workers return to their permanent places of residence. Approximately 18,008 (7.9%) of people identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander background (ABS, 2018). This is likely to be an underestimate. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in Townsville is almost twice the percentage of the state’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population (4.0%) (ABS, 2018). Over the last 100 years, there has been a movement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to Townsville and surrounding areas, much of this due to forced resettlement (particularly to Palm Island) enforced by successive Queensland state governments (Kidd, 1997). Palm Island is located 65 kilometres northeast of Townsville (Palm Island Centenary, 2018) and is home to approximately 4,000 people.

Townsville Hospital and Health Service captures Townsville (including Palm Island), stretching northwest to Mount Isa and north to Cooktown, Weipa, Bamaga and the Torres Strait Islands. Service providers in the region support and engage individuals from remote communities within the region. Although the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) is not a focus of this article, it is worth noting that the NDIS was launched in the Townsville region in July 2016 and that many of the disability professionals invited to participate in this research were representatives of services and organisations undergoing changes due to the NDIS national rollout. The service personnel interviewed for this research worked at the interface of disability support services and disability welfare-to-work services administered under the broader rubric of labour market activation policies and programming. Therefore, they had a strong understanding of the particular disadvantages and marginality of people with disability who no longer qualified for disability supports and payments with the ongoing eligibility restrictions. Often, because of their longstanding engagement in the area as regional residents, they were able to articulate clearly the impact of the legislative changes on their capacity to respond to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients living with disability, and the liminal class living ‘in between’ disability and non-disability social security qualification.

Participants and data collection

Disability professionals approached to participate in the interviews worked in the Townsville region, including Palm Island. The research team identified and approached a variety of different stakeholder groups that were regarded as highly knowledgeable of the disability income support payment system. Disability professionals were employed through disability-specific non-government organisations, generic human service NGOs, government and health departments, education and local government. Their core business was often varied and could involve advocacy, individual counselling, education and the production of written material, including reports. To this point, the term ‘service providers’ has been used to capture the diverse medical and non-medical organisations that support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients applying for the DSP. Non-medical professionals include disability employment services, general and Indigenous-specific support organisations, and community legal services. Medical professionals consist of doctors, health specialists and GPs.

Interviews and focus groups were conducted between March and May 2018 by the authors, with 21 participants for the Townsville and Palm Island regions. The majority of participants completed an interview or focus group, with a small number of participants completing both an interview and focus group. Interviews ranged from 16 to 90 minutes in duration. The focus groups ranged between 40 and 129 minutes in duration. A ‘snowball’ approach to recruiting participants was used whereby participants were able to recommend other relevant agencies in the region for the research team to approach.

A semi-structured interview guide consisted of broad questions such as: What services do you provide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disabilities who receive the DSP?; How have these changes impacted upon you as a service provider and your service more broadly?; What is your understanding of LGA (local government association) service provision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disabilities who are rejected from the DSP? The interviews and focus groups covered the following themes: service providers’ experiences supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals with a disability; how they have assisted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members to apply for the DSP; impacts to the delivery of their service following the series of changes to the DSP eligibility criteria and assessment process; how they communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their families about their disability and how this may impact the way Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disability engage with the DSP assessment process; and recommendations to improve the DSP application process.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis of the interview and focus group transcripts was conducted by the first author (MF) using an interpretive framework. All the transcripts were firstly read in full. The broad patterns of experience that appeared across the interviews and focus groups, both in relation to the specific research interests as well as other, unanticipated or emergent issues, were identified and labelled as themes. Material in the form of sentences and/or paragraphs was then coded manually into the themes, with multiple codes being used if the text fitted into more than one theme. This was in order to ensure that data and meaning were not lost. Thematic analysis was then used to break down, examine and compare material within the themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). To ensure validity, independent analysis of the material was carried out by author KS, with the content of the themes verified. Continuous discussion between the authors clarified minor points, including the meaning of quotes, and allowed for agreement on the development of the themes. To maintain the confidentiality of participants, details such as gender and the type of service where the participant was employed have not been provided with quotes.

Ethics approval

Approval was provided by the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) under H11920, Disability Income Reform in Regional Australia: The Lived Experience for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with Disabilities.

Regional service workers: contested navigations

In this research, a number of themes emerged from the participants’ responses related to the DSP. It is beyond the scope of this article to describe all themes in detail. This article focuses on how service providers supported Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disabilities during the new application process. The material categorised under this theme offers insight into how service providers have been affected by the federal government’s legislative changes to the rules and requirements determining eligibility to the DSP. Support provided to clients applying for the DSP fell into three sub-themes which are described and discussed below, supported with quotes from the service provider transcripts.

Adapting to new medical reporting requirements and work intensification

This sub-theme relates to medical professionals providing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients with medical evidence to support their application for the DSP. Before January 1, 2015, a medical report from an applicant’s treating doctor was the primary source of medical evidence for a DSP application (Australian Government, 2018b). Service providers described this earlier process, where a standard government-approved form was used for each client applying for the DSP, as streamlined. The new process requires medical professionals to complete a letter outlining each condition(s), prognosis and treatment (Department of Social Services, 2011). Medical professionals found this new process to be prolonged, as demonstrated by the following quote:

But now this new process where you physically have to do the letter yourself, each medical condition, when it was diagnosed, what the treatments have been, the prognosis, blah blah blah. It just takes forever.

Regular changes to the impairment tables without notification from the Department of Human Services created instability for service providers. Medical professionals stated it was common practice for colleagues to informally circulate information about these changes to the impairment tables when they became aware of them. This form of collegial professional circulation of information played a vital role in ensuring that professionals supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients with disability and/or chronic conditions worked with clients to obtain the necessary information to complete assessment forms and details.

Even with these informal efforts among professionals and practitioners to ensure their knowledge of the system was up to date, they found it challenging to formulate a letter or report to accompany a client’s DSP application under such conditions. Professionals had limited knowledge of the DSP assessor process and calculation of the points system, and therefore were not able to ascertain the types of information required in completing such reports (Department of Social Services, 2011).

It’s really hard to write letters that meet that criteria. Plus, we don’t know what the criteria is. […] We just write letters. We don’t know what the point system is, how many points they need to meet the – we just don’t have a clue.

This level of uncertainty created by the lack of information provided by the relevant government authorities to frontline practitioners significantly increased their workload due to the additional time required to, first, try to locate and understand the changing requirements, and second, to work with their clients to extract the relevant information necessary to complete the requirement documentation. Many of the medical professionals interviewed and part of the focus groups were not based at community clinics or health services full time. To ensure contact hours remained a priority, medical professionals were compelled to complete the necessary paperwork to accompany a client’s DSP application outside of contact/clinical hours, often within their own personal time.

In attempts to address the criteria, the professional participants of this study ensured key terms attached to the DSP criteria were used in medical reports to convey the level of impact the condition or illness had on a client’s functional ability to participate in work (Department of Social Services, 2011).

With the doctors, yeah. When I sit at [health service], and I can sit at [health service] and for a whole day do nothing but fill out DSP applications online […] Um, you know that the condition must be stabilised, and that the condition is not going to improve over the next 24 months …

Moreover, medical professionals also found the requirements of the letter or report problematic as the medical evidence was now required in a medico-legal format, rather than the standard medical report process in which they had been trained, as the following participant discusses:

[T]hey have to prove the functional impact of that medical condition and the medical data doesn’t prove that well. Um … so um, what we find is happening is that clients are being rejected. […] The other issue that has arisen is that we are then having to go back to doctors and ask them to provide reports that address the criteria, which we interpret or the medical community. What we’re asking them for is the medico-legal report. Doctors are not good at writing the medico-legal reports, they don’t have the time to write medical legal reports.

Almost all service providers described post-2015 reform access to the DSP as difficult. This experience is reflective of a broader trend in new recipient numbers since the start of the wider series of reforms to tighten eligibility criteria. According to Commonwealth Government figures, the proportion of DSP claims granted since the first round of changes to the impairment tables in 2012 had declined, with approximately 53 percent of DSP claims granted in July 2011 compared to 39 percent three years later in June 2014 (Australian National Audit Office, 2016). One participant recalled only one of her clients being granted the DSP since the 2015 reforms. The ideology underpinning these reforms is that individuals with typically non-permanent conditions have better prospects for employment participation with appropriate supports and should not be the long-term users of the DSP. Medical professionals found that clients with conditions considered treatable, for example cancer and mental illness, faced significant challenges in accessing the DSP. In the following quote, one participant described the rejection of an applicant with terminal cancer. In response, the service provider made direct contact with the local Centrelink office to discuss the rejection.

And then there was another one, he’s got [oral] cancer […] and he’s on oncology and radiotherapy; I mean it’s spread here, he’s got a peg [percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube], so in other words he can’t even feed properly, and he’s as thin as a rake because he’s living in nutrition, they turned him down as well. With him, I was so furious, I walked across to Centrelink and said, ‘what sort of animals do you think you are?’ And I really let rip. And he eventually got his, but I was so angry, that this guy has terminal cancer, and they still turned him down.

Rejection outcome letters from Centrelink were considered by participants as ambiguous, notifying applicants they had not obtained the 20 points required to be eligible for the DSP based on the information provided in the application regarding their condition(s). Medical and non-medical professionals described this as making it difficult for them to then offer clients informed guidance about the most appropriate option or options for their circumstances. The need for greater clarity and detailed explanations by the Department of Human Services in rejection letters generally was recognised in a 2014 investigation by the Commonwealth Ombudsman into service delivery complaints pertaining to the department (Australian National Audit Office, 2016).

Some medical professionals had taken steps to request greater communication between Centrelink regional office staff and medical and non-medical service providers, with other professionals recommending this. As the following quote illustrates, the purpose of the contact would be to supply service providers with information so they can adapt to the changing processes related to the DSP application and produce medical reports that accurately reflect the impact of a client’s disability.

No, no. We’ve asked that, in fact, I did, I actually phoned one of the Centrelink people up and said, ‘why is it we’ve been declined all the time. Why doesn’t somebody from Centrelink come and give us clear instructions about what we’re doing wrong that we cannot fill these letters?’ You know, why they fail. […] I’ve asked them to, but they didn’t. […] And they don’t want us to succeed, I believe. And I think that’s probably part of it. It’s so … I have asked several times, please, get somebody to come across and tell us how do we do this thing.

Some service providers saw this procedural change as discrediting the knowledge and integrity of medical professionals to be impartial when determining the level of disability of their client, as highlighted by the following quote:

Well maybe we need to actually go back to respecting the person’s GP and what they’ve said on a regular basis. And not presuming that they’re going to be biased to their patient. You know, respect that actually what they give is a reasonable assessment, because that’s what happened in the past. You were given GP reports, and it was resolved. […] So it’s an absolute insult to the medical profession, what’s going on. Because it’s saying you can’t be trusted, so we need these additional safeguards because we don’t trust what you’re saying. Well actually, the person’s GP is actually the best person to say this.

There was acknowledgement among both medical and non-medical professionals that the previous criteria for the DSP had to be adjusted to respond to the possibility that some individuals might falsify the level of their impairment. Yet the new DSP criteria were described by medical professionals as extreme, denying disability-specific support to many clients living with severe injury and illness.

Obtaining medical reports and information

Non-medical professionals supported Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients to obtain the relevant medical information and evidence to strengthen their DSP claims. Although outside core business activities, non-medical professionals commonly attended appointments with clients to advocate on their behalf. As illustrated by the following quotes, non-medical professionals recognised some clients required assistance to communicate with medical professionals about the documentation they required for the DSP application:

… definitely the lack of capturing of medical evidence and really not knowing the right questions to ask, or how to capture the information, there needs to be more support in that area.

And we’re just trying to help our Indigenous clients who need to get onto the DSP like comprehension, um, there’s lots of things that are really difficult. We try where possible to attend doctor’s appointments if we can …

Transport was identified as another barrier impinging on clients attending medical appointments to collect documentation for their DSP applications. Regional transport facilities were described as inadequate for people living with disability by non-medical professionals. Multiple non-medical professionals provided examples of clients who were required to catch two or three connecting buses to attend to submit paperwork to a Centrelink office or DSP assessment-related appointments. A financial cost was also linked to transport limitations. Clients were usually recipients of Newstart and unable to afford additional transport costs from their budget. The maximum fortnightly payment on Newstart for a single person with no children was $550.20 and $595.10 for a single person with a dependent child or children (Department of Human Services, 2018a). Accessing medical specialists for reports, as for recommended treatment options, was a significant financial burden for clients on Newstart as they received much lower benefits and subsidies on this general unemployment benefit than they potentially would on the DSP. Other transport limitations were related to not having a valid driver’s licence and access to a registered vehicle.

As part of the definition of ‘fully treated’, applicants have to demonstrate they have accessed treatment which is reasonably located and accessible to them and available at a reasonable cost (Department of Social Services, 2011). Demonstration of what was reasonable was considered by medical and non-medical professionals as a further barrier for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients. The following quotes illustrate how the cost of treatment and medical evidence can have an impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients fulfilling the DSP application requirements.

And also, the Medicare number that they used to be able to do reports under has been removed. So. if they’re being referred … Just making it harder and harder. So if clients are being referred for a medico-legal report, there is no Medicare number to put that under. So, clients are being asked to pay for those reports. And that’s a huge barrier for all people seeking Disability, but absolutely for Indigenous people seeking Disability. A much bigger barrier.

Absolutely, totally someone who needed a DSP, but for whatever reason just couldn’t get enough information, and the doc – the Centrelink weren’t accepting her medical certificates, even though her condition was permanent and stabilised, it was absolutely not, but because there was an opportunity to maybe see an orthopaedic surgeon to have an operation she couldn’t afford, and wait potentially five years for, and what does she do during that time? And yeah, they would not, it was just yeah, really frustrating.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients’ ability to access specialists in a timely manner to obtain relevant medical evidence was also identified as an issue. As illustrated by the following quote, people living in a regional or remote locality have poorer access to and use of health services than people living in metropolitan locations. For example, the number of GP services provided per person in very remote areas is about half that for metropolitan areas (Duckett et al., 2013). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in remote areas also have to travel long distances or relocate from their community or traditional lands to attend other health services not available in their community or receive specialist care. As illustrated by the following quote, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people interested in applying for the DSP in non-metropolitan areas are disadvantaged in completing the application requirements. Due to access limitations, they have not received a diagnosis or built a record of medical and specialist appointments related to their condition to demonstrate the condition being fully treated and stabilised:

And that’s a really big problem, because of course the medical system isn’t adapted for medico-legal needs, timetable to get into doctors, into specialists. Even accessing doctors and specialists in certain communities is a problem. Because to even get an assessment on the mental health table, you must have diagnosis by a clinical psychologist or a psychiatrist. Aboriginal people living in remote communities will not have easy access to either of those …

The new eligibility criteria were seen as indirectly victimising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who commonly did not engage well with the health system. As some non-medical professionals reported, providing pathways for clients to access new medical care usually resulted in clients being directed to other treatments and therefore restarting the two-year waiting period:

Another really practical issue that arises, is they come to me, and I go, right, we need the diagnosis by an appropriate doctor. So say you come in and you’ve got some sort of [inaudible], so well would it … the GP is unfortunately is [inaudible], so we need to get you to a specialist to have a look at your leg. As soon as you see a specialist, they don’t say, ‘oh well, let’s try this treatment’. You’re not fully diagnosed, got the diagnosis, not fully treated … well this person could try these additional treatments. So, any new doctor you see, if they’re a good doctor, is probably going to say, well how about we try some treatments.

Reporting and work activities exemptions

During the processes of collating medical evidence for their application, awaiting their application outcome, or submitting an application to appeal the outcome, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients were required to comply with their Newstart Allowance work and reporting requirements. It was common for clients of participants to wait between six and 12 months for the outcome of their application.

To respond to these circumstances, medical and non-medical professionals supported clients to manage Newstart Allowance expectations and ensure they were not ‘breached’ while waiting for the DSP application to be processed. Medical professionals provided participants medical certificates which temporarily exempted them from their Newstart activities and reporting:

… if they’re one of our chronics or whatever and they come in because they’ve got a sore knee or something else wrong, I will put them off for two or three weeks, because I know they should be off anyway. That’s how we get around it. […] There’s just – you know, I’ll do a Centrelink form [medical certificate], and put them off for a week or three weeks or whatever it is. And that’s how we get around the system.

A client’s medical condition usually affected their ability to meet their Newstart work and reporting requirements. Therefore, it was common for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients living with disability to seek more time to meet the requirements. This usually meant more than one medical certificate for the same condition being submitted to Centrelink for exemption consideration. Medical and non-medical professionals reported that they found Centrelink did not accept subsequent medical certificates with the same medical condition after one had previously been approved:

So that’s very hard for the job seekers. Like, they are unable to find employment. They are very sick. But if they will get – they have been exempted or suspended from the previous month, but then they’re still weak to the normal task, they are very ill. If they will get another three months exemption for all our medical certificate from their doctor and take it to Centrelink and again, what with [colleague] said, same terminology, Centrelink will then decline that.

I think they allow for up to three [months] normally. Then after that they’re like, doesn’t matter what the circumstance is. Kinda like, everyone gets the impression that Centrelink knows better, and they’re not medically trained either. […] So a lot of people at one stage were not even worrying about going and getting a medical certificate, because they knew Centrelink wasn’t going to accept it.

As illustrated by the quote above, on the basis of this Centrelink practice some clients did not report to a medical professional to document their inability to meet Newstart Allowance requirements due to their medical condition.

According to one participant, Centrelink denied further medical exceptions ‘because Newstart is not supposed to … to be on Newstart if you’ve a chronic condition, that’s what DSP is for.’Rejection of medical certificates resulted in the continuation of employment service and job search obligations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients deemed by medical professionals as unfit to work. According to non-medical professionals, not easing reporting and work activities contributed to client stress and ongoing poor health. Enforcement of clients to continue work-related activities was not beneficial for employers either, ‘because they’re [clients] deemed as unreliable’when failing to attend shifts or not completing work shifts in full.

Concluding discussion: social security, service innovation and Indigenous Australia

Changes to the DSP since 2015 have meant stricter eligibility rules and new assessment processes. According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, there has been a substantial drop in the number of individuals being granted the DSP (Parliamentary Budget Office, 2018). With this lower fiscal spending on disability social security payments, the federal government stands to save $4.8 billion over the next 10 years. These reports overshadow the serious implications placed on the day-to-day operations of medical and non-medical professionals who engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians living with disability. Substantial costs and responsibilities have been shifted to individuals applying for the DSP and the professionals that support them. This research is the first known to the authors to illustrate the unique impacts faced by such service providers working in regional centres and towns.

As many of the professionals articulated, the majority of individuals applying for the DSP are recipients of Newstart Allowance, a significantly lower payment with fewer benefits and subsidies. This is in addition to the extensive social security conditionality that forces this group to participate in a range of welfare-to-work activation programs to maintain access to this general unemployment benefit (Hinton, 2018). The Newstart Allowance is not an adequate financial base to support the DSP application process for many recipients. At the time of writing, there are extensive campaigns to ‘raise the payment rate’ of Newstart so it covers the daily cost of living. This does not include the additional costs associated with extensive medical and testing requirements to build the necessary body of evidence for DSP assessment. To obtain the required medical evidence and documentation for the application, individuals are compelled to spend their Newstart payments on attending multiple medical appointments. This study identified that it is common for individuals to not have the financial means to fulfil this application process.

The reforms have also been enacted without sensitivity to how individuals can satisfy the requirements in regional and remote areas. Our results show Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people face several barriers that prevent them from obtaining the appropriate medical evidence to satisfy the DSP eligibility criteria. Despite Indigenous Australians comprising 2.3 percent of the national population, only 1.6 percent of Australian general practitioner consultations were with Indigenous people (Britt et al., 2012). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are often prevented from accessing health care due to many factors, including the high cost of health care, experiences of discrimination and racism, disempowerment and poor communication with healthcare professionals (Aspin et al., 2012; Burnett & Kickett, 2009; Durey & Thompson, 2012). These experiences can prevent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians seeking medical advice and treatment, a process that is central to building a body of evidence for a DSP application. In addition, access to general practitioners and specialists worsens with increasing remoteness. In 2015, there was a decline in full-time equivalent medical practitioners as remoteness increased, from 442 per 100,000 population in major cities to 263 in remote / very remote areas (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016). In response, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians can be required to travel long distances to access specialised health care. With low rates of driver licence ownership and limited public transport (Clapham et al., 2008), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in regional and remote localities can experience challenges to adequately demonstrate their conditions are fully stabilised and fully treated.

In response to DSP reforms, medical and non-medical professionals have developed a variety of innovative service-level and client contact-level processes, including dissemination of DSP-related updates among colleagues and assisting clients to assemble their DSP applications and obtain appropriate medical evidence. Service providers also assist clients with obtaining medical exemptions from their Newstart Allowance activities to manage system conditions, including lengthy processing times for DSP applications. The impact to non-medical professionals in North Queensland is comparable to the staffing impacts in non-government organisations in other Australian states (Hinton, 2018). The creative strategies the participants in our study utilised are outside the mandate of their professional roles and are therefore unaccounted for in staffing and resource budgets, with the cost of supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients applying for the DSP absorbed by service providers. Medical and non-medical professionals state that their responses to the reforms can be substantially improved through greater outreach, engagement and dissemination of information from the Department of Human Services of the changing disability support landscape. The experiences of medical and non-medical professionals also illustrate the necessity in a large-scale reform process of seeking and incorporating feedback from service providers who engage and interact with clients.

Since 2007, Australian governments have publicly articulated an intent to ‘close the gap’ on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ill health and chronic illness alongside broader indicators of social and economic inequality, when compared to non-Indigenous Australians. Yet, in examining reforms to Australia’s social security system over this time, particularly the DSP, it remains clear that the embedding of the activation logic of neo-liberal welfare-to-work conditionality alongside the requirement for more stringent assessment processes is critically failing the realisation of the ‘close the gap’ goals and targets. The ongoing retraction and restrictions by Australian Government’s to the right to social security, as articulated within ILO C.169, is directly undermining the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders living with disability. As this article documents, professional frontline workers are trying to ameliorate the worst excesses of a more restrictive social security system, enduring longer working hours and work intensification to ensure that services remain accessible and inclusive of their Indigenous clients living with disability.

References

Aspin, C., Brown, N., Jowsey, T., Yen, L., & Leeder, S. (2012). Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic illness: a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research 12, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-143.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012a). 4430.0 Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012b). 4433.0.55.005 – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a Disability. Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Census 2016. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/census.

Australian Government. (2018a). Guides to Social Policy Law: Social Security Guide. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved 17/9/2018 from http://guides.dss.gov.au/guide-social-security-law/1/1/j/10

Australian Government. (2018b). 3.6.2.10 Medical & Other Evidence for DSP, in Guides to Social Policy Law: Social Security Guide. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved 17/9/2018 from http://guides.dss.gov.au/guide-social-security-law/1/1/j/10.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2016). Medical practitioners workforce 2015. Canberra: Australian Government.

Australian National Audit Office. (2016). Qualifying for the Disability Support Pension. Canberra: Department of Social Services. Retrieved 21/9/2018 from https://www.anao.gov.au/sites/g/files/net5496/f/ANAO_Report_2015-2016_18.pdf.

Beer, A. (2012) ‘The economic geography of Australia and its analysis: from industrial to post-industrial regions’, Geographical Research, 50 (3), 269–81.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77–101.

Britt, H., Miller, G.C., Henderson, J., Bayram, C., Harrison, C., Valenti, L., Wong, C., Gordon, J., Pollack, A.J., Pan, Y., & Charles, J. (2012). General practice activity in Australia 2011-12, in BEACH Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Burnett, L., & Kickett, M. (2009). ‘You are just a puppet’: Australian Aboriginal people’s experience of disempowerment when undergoing treatment for end-stage renal disease. Renal Society of Australasia Journal 5(3): 113.

Clapham, K., Senserrick, T., Ivers, R., Lyford, M., & Stevenson, M. (2008). Understanding the extent and impact of Indigenous road trauma. Injury 39(Supplement 5): S19–23.

Dalton, T., & Ong, R. (2007). Welfare to work in Australia: Disability income support, housing affordability and employment incentives. European Journal of Housing Policy 7(3): 275–97.

Department of Human Services. (2018a). Newstart Allowance: How much you can get. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved 21/9/2018 from https://www.humanservices.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/newstart-allowance/how-much-you-can-get.

Department of Human Services. (2018b). Program of Support for Disability Support Pension. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved 20/9/2018 from https://www.humanservices.gov.au/individuals/enablers/program-support-disability-support-pension/29776.

Department of Social Services. (2011). Social Security (Tables for the Assessment of Work-related Impairment for Disability Support Pension) Determination 2011. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved 21/9/2018 from https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/disability-and-carers/benefits-payments/disability-support-pension-dsp-better-and-fairer-assessments/review-of-the-tables-for-the-assessment-of-work-related-impairment-for-disability-support-pension/social-security-tables-for-the.

Duckett S, Breadon, P., & Ginnivan L. (2013). Access all areas: New solutions for GP shortages in rural Australia. Melbourne: Grattan Institute.

Durey, A., & Thompson, S.C. (2012). Reducing the health disparities of Indigenous Australians: time to change focus. BMC Health Services Research 12(1), 151. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-151.

Grover, C., & Soldatic, K. (2013). Neo-liberal restructuring, disabled people and social (in)security in Australia and Britain. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 15(3), 216-232.

Hinton, T. (2018). Paying the price of welfare reform: the experiences of Anglicare staff and clients in interacting with Centrelink. Hobart, Tasmania: Anglicare. Retrieved 21/9/2018 from http://www.anglicare.asn.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/report-brief.pdf?sfvrsn=0

International Labour Organization. (1989). C169 – Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169).

Jordan, K. (2018). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment policy and Welfare to work: the Community Development Programme and the need for new narratives, new alliances and new institutions. Australian Journal of Social Issues. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.42

Kandasamy, N. & Soldatic, K. (2017). ‘Implications for practice: exploring the impacts of government contracts on refugee settlement services in rural and urban Australia’, Australian Social Work, 71(1), 111-119.

Kidd, R. (1997). The way we civilise. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Morris, A., Wilson, S., & Soldatic, K.M. (2015). Doing the ‘hard yakka’: implications of Australia’s workfare policies for disabled people, in C. Grover & L. Piggott (Eds.), Disabled people, work and welfare: is employment really the answer? Bristol: Policy Press, 43-68.

Neave, C. (2016). Department of Human Services: accessibility of Disability Support Pension for remote Indigenous Australians, Canberra: Commonwealth Ombudsman. Retrieved 21/9/2018 from http://www.ombudsman.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/42558/Accessibility-of-DSP-for-remote-Indigenous-Australians_Final-report.pdf.

Parliamentary Budget Office. (2018). Disability Support Pension. Historical and project trents (report no 01/2018). Canberra: Parliament of Australia. Retrived 24/9/2018 from http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/

Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Budget_Office/Publications/

Research_reports/Disability_support_pension_Historical_and_projected_trends

Palm Island Centenary. (2018). Our history: About Palm Island. Retrieved 21/9/2018 from https://palmislandcentenary2018.com.au/our-history/.

Soldatic, K., Somers, K., Spurway, K. & van Toorn, G. (2017) ‘Emplacing Indigeneity and rurality in neo-liberal disability welfare reform: the lived experience of Aboriginal people with disabilities in the West Kimberley, Australia’, Environment and Planning A, doi: 10.1177/0308518X17718374.

Soldatic, K. (2018a). Neo-liberalising disability income reform: what does this mean for Indigenous Australians living in regional areas? in D. Howard-Wagner, M. Bargh & I. Altamirano-Jiménez (eds), The neo-liberal state, recognition and Indigenous rights. Canberra: ANU Press, 131–146.

Soldatic, K. (2018b). Policy mobilities of exclusion: implications of Australian disability pension retraction for Indigenous Australians. Social Policy and Society 17(1), 151–167.

Soldatic, K. (2019). Disability and Neo-liberal State Formations. London: Routledge.

United Nations. (2007). Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.A/RES/61/295.

Acknowledgements:

This research has been funded by an ARC DECRA Fellowship (DE160100478), Disability Income Reform and Regional Australia: The Indigenous Experience.

About the authors

Dr Michelle Fitts has a diverse research background within public health, psychology and disability. Her multiple areas of research interest – traumatic brain injury, road safety, alcohol management and disability in Indigenous Australian communities are drawn together through the theme of injury prevention. Over the last ten years her work has contributed to a range of policy and practice changes and the development of educational resources and programs including a community-based drink driving program for regional and remote Indigenous communities. Her work has been recognised with a number of awards including the prestigious Peter Vulcan Award.

Email: michelle.fitts1@jcu.edu.au

Dr Karen Soldatic is an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow (2016-2019) at the Institute for Culture and Society at Western Sydney University. She was awarded a Fogarty Foundation Excellence in Education Fellowship for 2006–2009, a British Academy International Fellowship in 2012 and a fellowship at The Centre for Human Rights Education at Curtin University (2011-2012) where she remains an Adjunct Fellow. Her research on global welfare regimes builds on her 20 years of experience as an international, national and state-based senior policy analyst, researcher and practitioner. She obtained her PhD (Distinction) in 2010 from the University of Western Australia.