Emotional strategies in Nazi propaganda films: Two case studies

Stefani Deligiannis

Western Sydney University

Abstract

This article aims to enrich our understanding of National Socialist (Nazi) propaganda by taking a history of the emotions approach to a case study of two iconic Nazi films: Triumph des Willens and Olympia. Although few periods in European history have received as much attention as Nazi Germany, there remain meaningful gaps in knowledge of how one of the most brutal totalitarian systems came to be so compelling and persuasive to large numbers of Germans. Historians such as Karl Dietrich Bracher (1970) have argued that Nazi success can only be explained by the role of Third Reich propaganda. While it has been argued that propaganda played a pivotal role in the entire apparatus, the ability of Third Reich propaganda to exploit emotional vulnerability has attracted significantly less attention. The ‘brainwash’ theory of propaganda has long been discarded as it fails to consider the individual’s ability to resist the ideas presented to them. This article is concerned with the role of emotions as central to the propaganda success of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP).

Introduction

While propaganda was not invented by the National Socialist (Nazi) Party or the Reich Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, its use in Nazi indoctrination practices is responsible for its perennial association with Nazism. The notion of propaganda, however, began to acquire negative connotations much earlier, occasioned by its widespread use during World War I, and later becoming synonymous with communist and fascist techniques of state and population control. As a result, the word ‘propaganda’ now often evokes images of deceit and manipulation (Culbert & Welch, 2003). Goebbels himself stated:

I cannot convince a single person of the necessity of something unless I get to know the soul of that person, unless I understand how to pluck the string in the harp of his soul that must be made to sound (Culbert & Welch, 2003, p. 17).

Although anti-Semitic ideas and other aspects of Nazi ideology were critical to Nazism’s popular success, the deft deployment of propaganda in the Third Reich to harness emotions and motivate behaviours warrants further investigation. This article focuses on two emotions targeted by Nazi propaganda: German humiliation through Dolchstoßlegende (stab in the back myth), and nationalism as an emotion, as conveyed in two infamous propaganda films of the early Nazi period: Triumph des Willens and Olympia.

The frameworks and conceptual vocabularies developed in the emerging interdisciplinary field of the history of emotions have given us new tools for understanding how emotional appeals and Nazi propaganda worked, with particular focus on the collective experience of shared emotions. These theoretical tools provide insights into the way Nazi propaganda worked, with particular focus on the collective experience of shared emotions. Focusing on radio and print media, philosopher and media theorist Marshall McLuhan (1967) highlighted how propagandists understood the value of seizing attention and attracting groups of people by targeting values and emotions. McLuhan draws attention to the primordial influence of the disembodied voice as instrumental in establishing and maintaining the appeal of fascist regimes.

Similarly, film re-embodies this primordial influence by linking the power of the spoken word to the visual. It is important to appreciate the considerable and often demanding task of sound and visual editing during this time. In 1936, directors did not have the tools to simplify the task of editing (Hilton, 2000). Leni Riefenstahl, one of the most prominent Nazi propaganda filmmakers, used an array of techniques to sustain gripping moments throughout every scene of her films. State-of-the-art, avant-garde film technology was a pivotal component of Nazi film propaganda, which served many purposes, not least of which was to position Nazi Germany as a dominant European power. This modern technology was also very effective in invoking inspiration and admiration for Nazism as mass support and mobilisation demanded a foundation of enthusiasm and positive emotion. Nazi propaganda targeted patriotic groups, anti-communists, disenchanted liberals, defeated veterans of the Great War, and the socially, and economically vulnerable, all of whom responded to the narrative of national humiliation and betrayal.

Hitler emphasised the power of continuous suggestion and simple messages, claiming that the purpose of propaganda was to direct people’s attention to essential matters by consistently placing them within their view (Hitler, 1926). He maintained that propaganda needed to be simple, focusing on a few points that were continuously repeated, with specific emphasis on positive and negative emotions (Shirer, 1941). A well-known example is Hitler’s rallying slogan ‘Germany, awake!’, a cry for salvation that aimed to galvanise a nation in turmoil with its identity shaken after a lost war (Falk, 2006, p. 39). This slogan was to be chanted to create a sense of ‘us’ against the Jews and the ‘enemies of Germany’.

Historians of Propaganda and the Third Reich

While there is extensive literature on Third Reich propaganda, insufficient work has been done on its emotional appeal. British historian of propaganda Aristotle Kallis (2005) notes that propaganda has often been associated with deception, manipulation and misinformation. Early in the 20th century, propaganda was:

… deployed generically to indicate a systematic process of information management geared to promoting a particular goal and to guaranteeing a popular response desired by the propagandist (Kallis, 2005, p. 11).

As such, Kallis argues that propaganda is a means of public communication and persuasion, developed in the context of modernity to serve the insatiable demand for information and opinion-forming. One of the leading theorists of propaganda and communication, Jacques Ellul (1971) writes that propaganda arose out of a need to prioritise, organise, correlate and then transmit information to the interested public, involving both providing and withholding information. Similarly, David Welch’s (2004) notable contribution to the historiography of 20th-century propaganda highlights the role of historical narratives in driving National Socialist (Nazi) propaganda. Welch scrutinised the Nazi vision of a Volksgemeinschaft (national community) that defined racial ideals to effectively separate those who were deemed to belong to this community, from those who were excluded from it (Welch, 2004, p. 214). Narratives of racial purity bred the ‘Aryan’ myth of the German ‘race’ that underpinned historical tales about degeneration and the need for a German nationalist revival (Welch, 2004). However, Welch demonstrated that the Nazis also understood that propaganda was of little value in isolation.

Historians have recently shifted their focus from the ‘brainwashing’ aspect of propaganda to emphasise the role of pre-existing beliefs in determining its effectiveness. Similarly, Aristotle Kallis challenges the notion that any form of effective propaganda results in ‘brainwashing’. In his book Nazi Propaganda and the Second World War, Kallis writes that propaganda cannot assume values can be changed within its target audience, as this would risk losing support and encountering far stronger resistance. He claims that it was through undermining the validity of well-established attitudes over a long period and complying with other values that society already shares that successful propaganda can achieve ‘long-term, gradual attitudinal change through sustained exposure to an alternative’ (Kallis, 2005, p. 35). In short, the most effective propaganda maintains a dialogue between traditional social principles and its alternative prescriptions by using some of the vocabulary, terminology and imagery of the existing value system (Keshaw, 2002, p. 169).

The Nazi party’s exploitation and amplification of existing and entrenched anti-Semitism in Germany has been explored by many historians. Emphasising feelings of shame across Germany following the outcomes of World War I and apportioning blame to the Jewish population, was a central feature of the Nazi propaganda narrative (Deutch & Yanay, 2018, p. 24). This example resonates with Kallis’ understanding that propaganda messaging complies with existing sentiments and beliefs or at least does not violate them. The motif of the morally corrupting and diseased influence of Jews played an important role. It was important to define ‘non-Aryans’ who represented the racial threat to the state.

Anti-Semitism has been described as more than an idea, but rather, a passion (Sarte, 1944). While there is a vast corpus of works on the motif of the morally corrupting influence of Jews, few historians have explored the connection between the history of emotions and anti-Semitism. Historian Daniel Goldhagen (1997) claims that Germans were able to be persuaded to commit genocide because of their visceral hatred of Jews. While controversial, it is important to acknowledge that Nazi propaganda exploited existing anti-Semitism. Historians of emotions have often focused on specific adverse feelings, such as hatred, resentment or disgust, in isolation from positive emotions, while historians of anti-Semitism often focus exclusively on the prejudices against Jews. In this regard, anti-Semitism in the Third Reich would benefit considerably from an integrated approach to this history of emotions. Nazi anti-Semitic discourse mobilised emotions such as hatred, anger, fear, disgust, resentment, nostalgia and pride and frequently condemned Jewish behaviour as immoral toward the goal of collective sensitisation followed by desensitisation. First, it sought to arouse disgust for the Jewish presence, which soon paved the path toward aggression and mistreatment of European Jewry as a precondition for racial purification of the nation.

Tracking the emotional trajectory of Nazi propaganda can shed insights into the question of the complicity and responsibility of ordinary Germans in the Nazi era. Daniel Goldhagen’s (1997) work, Hitler’s Willing Executioners, contends that everyday Germans were not only complicit but also active participants of genocide outside of concentration camps. Historians such as Hannah Arendt (2007) have also proposed that a new kind of historical subject may have become possible with national socialism, one in which a crime against humanity could become in some sense ‘banal’ because it was committed in a daily way, systematically, without being adequately named and opposed (Arendt, 2007, p. 117). Hence, the ‘banality of evil’ was how the crime had become for the criminals accepted, routinised, and implemented without moral revulsion and political indignation and resistance.

Since the early 2000s, historians have joined in the conversation with other scholars regarding the emotive force of propaganda, suggesting fruitful lines of inquiry by discussing the history of propaganda in the context of the history of emotion. This shift in understanding challenges the misconceptions associated with propaganda which have emphasised its role in transforming attitudes and beliefs. While the rational level of persuasion may be one objective, it is not the only dimension of effective propaganda. For propaganda to be effective, a message must not only be constructed and transmitted but it also must be received and accepted. Audiences actively select messages that conform to their predetermined values and beliefs that will perceivably improve their circumstances (Kallis, 2005, p. 13). In their 2003 book Propaganda and Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present, historians Nicholas J. Cull, David Culbert and David Welch (2004) identified how effectively communicating ideas to others requires a combination of both reason and emotion:

… if propaganda is too rational, it could become boring; if it is too emotional or strident, it might become transparent and ludicrous (p. 21).

It is the propagandists’ task to analyse their audience and context by using the methods they deem most effective to convey their message. Such scholars imply that if we broaden the scope of reference and purge propaganda of its disparaging connotations, it may be recognised as a crucial part of the political process and as having a vital role in stimulating active participation in the democratic process (Taylor, 1995, p. 129). These ideas have introduced a new avenue of inquiry for historians and highlight the need to apply the history of emotions to a case study of National Socialism.

The history of the ‘emotions’ approach

Whilst leading French historical thinkers Lucien Febvre (1878-1956) and Marc Bloch (1886–1944) stressed the importance of emotions as an historical force as early as the 1920s, the field only came into its own in the 1980s and 1990s. The ‘emotional turn’, as it has been termed within the academy, refers to a shift in history during the late 20th century to an increasing focus on the role of emotions in shaping historical events, cultures and social dynamics. The ‘emotional turn’ has influenced not only history but an array of humanities and social science disciplines as it seeks to emphasise emotion both as culturally distinctive and as agentic in shaping social conditions and relationships (Barclay, 2021). The latter is especially significant in moving understandings of emotion as a biological ‘response’ to an external stimulus, an active component of the experience that can be explained and which in turn helps us explain events. Historians of emotion emphasise that emotions are products of their cultural environments. They build upon a philosophical tradition that highlights the relationship between language and human experience, where the words we use give form and shape to our worlds. This is not to deny that humans are also material: we have bodies, and those bodies act as constraints in some important ways on our experience (Barclay, 2021, p. 456).

The history of emotions gained further traction and acquired a new sophistication by the early 21st century, when studying the history of emotions became a recognised area of inquiry, with numerous conferences, journals, and publications dedicated to the subject. Scholars like Barbara H. Rosenwein (2015) made noteworthy contributions to the field with her work on ‘emotional communities’. The field also made significant progress with the awarding of a record-breaking and widely publicised grant of $24AUD million for an ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions in 2011. Rosenwein developed the concept of ‘emotional communities’ as a way of thinking about the social formation of emotion. She argued that social groups possess systems of feeling by which they define and assess certain feelings as valuable or harmful and are therefore something to be endorsed or avoided.

Firth-Godbehere, one of the leading experts on disgust and emotions, argues that both culture and biology matter (2021, p. 41). Emotions are not just personal experiences, nor universal and fixed. What people feel and how they express their emotions is deeply influenced by cultural, historical, and social contexts. Historians have observed that even the names of emotions have evolved, leading to shifts in their meanings. How individuals experienced emotions such as disgust, fear, anger and desire in the past has shifted over time. For example, the English word ‘disgust’ once referred specifically to unpleasant tastes, but now encompasses aversion to anything distasteful.

William M. Reddy is a prominent scholar in the field of the history of emotions and is best known for his concept of ‘emotional regimes’, one that highlights how cultural ideas about emotion become implicated in political systems, where people who conform to the norm are rewarded, and those who do not are punished. The idea has been similarly useful at providing mechanisms to explain the social and political functions of emotion (Reddy, 2001, p. 128) and is especially useful for tracking how an emotion may become an ‘active’ historical agent. Like Firth-Godbehere, Reddy considered emotions to be formed culturally and historically without denying their universal corporeal core. He emphasised the ‘emotive’, where the act of naming or vocalising a feeling in the body was part of what produced it. In this way, the embodied experience and culture reinforce each other, and the ‘emotive’ is the emotion term whose use enabled that experience to happen. Reddy also coined the term ‘emotional refuge’ — whereas an emotional regime is a dominant form of emotional expression, a ‘refuge’ would be the style that develops in resistance to it. that is when people vent their suppressed true emotions.

This idea is supported by Alie Hochschild (2015) in her concept of ‘emotional labour’ which refers to the effort to induce or suppress feelings to express countenance towards others — the effort put in to adhere to the ‘emotional regime’ (Rosenwein, 2015, p. 142). Finally, Monique Scheer draws upon Pierre Bourdieu’s (2017) concept of habitus, to suggest that emotions are a form of practice: things that were learned from infancy and experienced as naturalised responses (Scheer, 2012). Like Reddy, Scheer also suggests that the process of naming and identifying emotion directs our embodied experience. One of the results of these ideas is that the history of emotions particularly attends to how emotions are defined, described, and applied by individuals and groups (Barclay, 2021). As a result, the history of emotions has emerged as a sub-discipline or approach which offers new tools and conceptual vocabularies to help enhance historical understanding of the impact of propaganda.

Nazi propaganda and popular mobilisation on film

Nazi Germany was one of the first European powers to exploit emergent film technology to extend its reach into popular culture. Film was an important means of disseminating political objectives to the public because of its unassuming nature (Hoffman, 1996). German writer and renowned film theorist Siegfried Kracauer closely examined German society during Hitler’s rise to prominence. His work Film Theory provides a connection between the escapist and apolitical orientation of the Weimar Republic cinema and later German totalitarianism (Kracauer, 1947). He wrote: ‘to be sure, all Nazi films were more or less propaganda films — even the mere entertainment pictures which seem to be remote from politics’ (p. 275). Following Hitler’s rise to the Chancellorship in 1933, Goebbels moved swiftly to control the film industry. In 1936, Goebbels prohibited foreign films and outlawed film criticism, replacing it with ‘film observation’, which only permitted journalists to describe films, not critique them (von Tunzelmann, 2012).

German filmmaker, Fritz Hippler directed the film department in the Propaganda Ministry of Nazi Germany under Joseph Goebbels. Joining the party at the age of seventeen, Hippler became a member of Sturmabteilung (SA) and was an active member in the 1933 burning of ‘un-German’ books. He directed several prominent Nazi propaganda films such as Der ewige Jude [The Eternal Jew], Feldzug in Polen [Campaign in Poland] and Die Frontschau [The Front Review] (Winkel, 2003, p. 94). In his diary, he makes clear that Riefenstahl’s use of film techniques was a deliberate strategy to captivate people and garner support for Nazism. Hippler (1937) wrote:

In comparison with the other arts, film has a particularly forceful and lasting psychological and propagandistic impact because of its effect not on the intellect, but principally on the emotions and the visual sense. [Film] does not aim to influence the views of an elite coterie of art experts. Rather, it seeks to seize the attention of the broader public. As a result, film can exercise an influence on society that is more enduring than that achieved by church, school or literature, or for that matter, literature, the press or radio. Hence, for reasons that lie outside the realm of art, it would be negligent and reckless (and not in the interest of the arts themselves) for a responsible government to relinquish its leadership role in this important area.

Hippler’s statement is an explicit reference to the psychological and emotional impact of film propaganda as he understood it, and the reasons National Socialism adopted film as a fundamental propaganda tool. Film was not an opportunity to win over artists and film experts, but to capture the hearts and minds of a vulnerable and impressionable German population. What distinguished the National Socialists’ propaganda from liberal democratic propaganda was the vision, forcefulness and mesmerising emotionalism (Hoffman, 1996, p. 74). Chief architect of Nazi Germany, Albert Speer, stated in the Nuremberg Trials that:

… what distinguished the Third Reich from all previous dictatorships was its use of all the means of communication to sustain itself and to deprive its objects of the power of independent thought (Ellul, 1965, p.11).

Film has the power to activate what neurologists refer to as emotional triggers, which the brain uses to conserve the energy required for analytical thinking (Finger, Boller & Tyler, 2009, p. 390). Tapping into these functions enables swift and intense decision-making. Insights drawn from a body of literature on crowd psychology, which emerged in the late 19th century, are rooted in Charles Mackay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841) and were further popularised by Gustave Le Bon’s work from the 1890s onwards. While historians have long been aware that Nazi propaganda aimed to have an emotional appeal, the nature of this transaction is not well understood. The following sections discuss two prominent examples of Nazi propaganda films and how they adopted the persuasive features of the nascent film medium to their propaganda ends.

Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will)

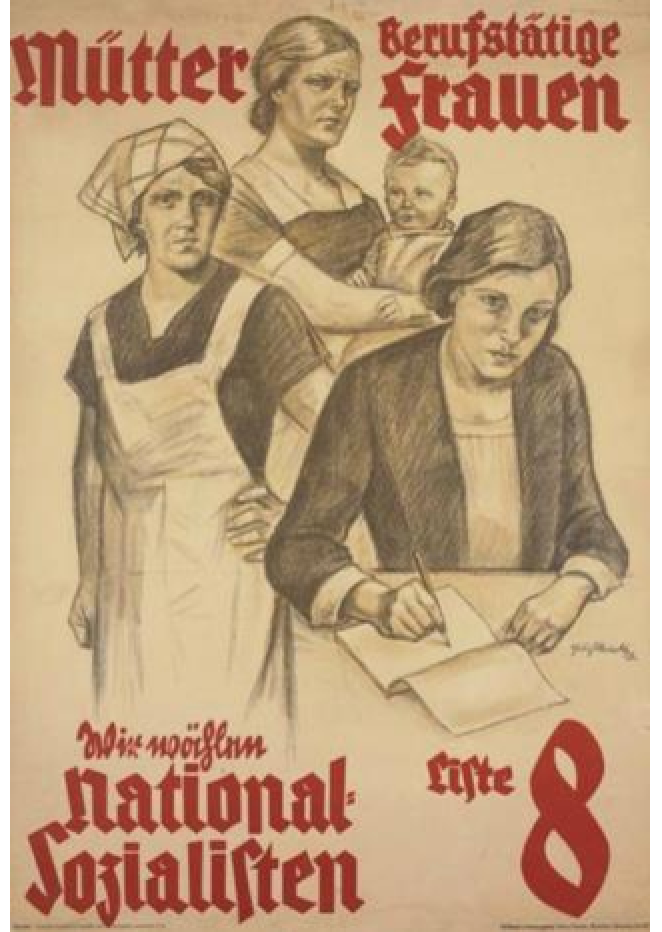

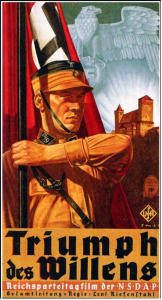

Figure 1: Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will): Courtesy of the National Film Archive

Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will), created by prominent German film producer Leni Riefenstahl, is considered to be Nazism’s propaganda masterpiece (Figure 1). The picture opens with a large caption on a black screen which reads:

On 5 September 1934, 20 years after the outbreak of the World War, 16 years after the beginning of German suffering, 19 months after the beginning of the German rebirth, Adolf Hitler flew once again to Nuremberg to review the columns of faithful followers’ (Riefenstahl, 1935, 00:16:00).

In the aftermath of World War I, a demoralised German population lived in a state of uncertainty, enduring radical social change, surging unemployment and economic and political instability (Dismandle, Horsewood & Van Riel, 2006). By introducing the film in this way, German audiences were reminded of their suffering and presented with a solution in the messianic figure of Hitler. In short, the film begins with a focused psychological manipulation of humiliation, pride, and hope. By insisting that the German army was not defeated but rather betrayed by Jews, republican politicians and revolutionary socialists, Hitler embedded the Dolchstoßlegende (stab-in-the-back) legend, which emphasised betrayal and humiliation, thus defining a clear enemy. Moreover, Hitler distinguished himself as a leader who shared in the pain and grief of the German people, During a speech in Munich in 1929, Hitler ardently declared that:

… we will be concerned day and night with the question of how to produce the armed forces, which are forbidden us by the peace treaty [Treaty of Versailles] … We confess further that we will dash anyone to pieces who should dare hinder us in this undertaking … Our rights will be protected only when the German Reich [country] is again supported by the point of the German dagger (Hitler, 1929).

Hitler’s oratory prowess is worthy of mention. His use of first-person pronouns ‘we’ and ‘us’ bridged the gap between the leader and the public. The pain and suffering of the German people was framed as his own.

Triumph of the Will launches into an array of long shots capturing eager crowds cheering and smiling as Hitler drives by, waving at his enthusiastic followers (Riefenstahl, 1935, 00:07:45). When speaking to the ideologically committed to motivate behaviour, there needs to be an appeal to enthusiasm and positive emotion, as these elements are crucial in fostering a strong sense of national identity and solidarity which can energise individuals to actively participate in the promotion of nationalist ideals and goals. There is a complex interplay between patriotism as an ideology and nationalism as an emotion. Nationalistic sentiments are an emotional attachment to one’s (imagined) national community and are particularly susceptible to emotional appeals. Ideology, in this sense, provides a vocabulary of outward expression for internal responses (Welch, 2004, p. 213). Political scientist and historian Benedict Anderson conceptualised nationalism as a form of personal identity that creates bonds of loyalty and love to an imagined community (Anderson, 1991). Nationalism is emotionally embedded in human desire for belonging and identity, a nation is as much an ‘emotional community’ as an ‘imagined’ one. Nazi propaganda sought to mobilise emotion over reason; people were encouraged to feel rather than think.

In Triumph of the Will, extreme high and low-angle shots of Hitler delivering his speeches position him as the commander of an empire of flawlessly synchronised subjects. Swastikas fill almost every scene (Riefenstahl, 1935, 00:20:00). Riefenstahl declared that:

… in 1934 people were crazy and there was great enthusiasm for Hitler. We had to try and find that with our camera (Sontag, 1966, p. 34).

The assemblage of cinematic techniques was made to convey the thrill of becoming part of the Nazi movement. The American journalist William L. Shirer (1941), newly arrived in Germany, witnessed the Nuremberg rally in Triumph of the Will first-hand. He described his experience:

About ten o’clock tonight I got caught in a mob of ten thousand hysterics who jammed the moat in front of Hitler’s hotel, shouting: ‘We want our Führer.’ I was a little shocked at the faces, especially those of the women, when Hitler finally appeared on the balcony for a moment … They looked up at him as if he were a Messiah, their faces transformed into something positively inhuman (p. 17).

While Shirer’s sensationalist writing was worded and selected to excite readers, it does highlight more significant ideas about the impact of Nazi masculinism in the film. Shirer’s sentiments suggest that he was surprised that the Fuhrer’s masculinism appealed so strongly, and perhaps especially to women. Hitler’s ability to unite crowds of men, women and children opened doors for new associations and contributions from all people. In regime rhetoric, women and youth were regarded and celebrated as vital and valued political supporters and participants in the Third Reich.

The Nuremberg rally described by Shirer and as captured by Riefenstahl played on desires for belonging and revival. Now, for the first time, since the disillusionment of the Great War, people were encouraged to feel proud of Germany and its leadership. Writing in Mein Kampf, Hitler noted:

… the individual leaves their small workplace or the big factory, where they regard themselves a little person, and enters for the first time a mass meeting and is surrounded by thousands and thousands of people of the same conviction, and they as a searcher gets caught in the mighty effect of the suggestive Rausch and enthusiasm of three- to four thousand others, […] in this moment they fall under the sway of what we call mass suggestion (Hitler, 1925).

The term ‘Rausch’ cannot be defined in simple terms because its meaning changes according to different lexical fields and discourses. Nonetheless, it has been used to describe both individual and collective experiences of intoxication or ecstasy in relation to Nazism (Bayai, 2003, p. 16). Rausch describes the emotional processes associated with being entirely part of a movement — it is the power and exaltation associated with the fusion of a collective body (Kilmo, 2004). The idea of a subdued German worker whose honesty and hard work had not previously been recognised was pivotal to nationalist discourse following the First World War. Hitler targets the everyday individual who feels dejected and unimportant until they are suddenly captured by the collective experience of heightened emotion and being part of something greater. The Nuremberg rally scene reinforced the perception that Hitler was reviving Germany after the failures of the ill-fated Weimar Republic. The purpose of the documentary-style film was to give visual form to a rejuvenated nation where previously there had been only despair and instability (Chornyi, 2019, p. 10). Every German citizen played a distinct role in shaping Germany’s heroic future. Schutzstaffel (SS) and Sturmabteilung (SA) soldiers are seen to be establishing law, order and discipline, in stark contrast to the chaos of the Weimar years (Riefenstahl, 1935, 00:32:30). Peasant families with shovels in their hands are depicted bringing the product of their labour to the Party Rally; young boys are presented as the future leaders of the nation who will ensure a bright future (Riefenstahl, 1935, 00:19:00). The use of idealised white bodies as a counterpoint to the deformed, hook-nosed Jew in Nazi imagery was also important. The film showed inclusivity in filming women and children as part of the Volk but also showed an exclusively Aryan ideal of Nordic whiteness with a preference for depicting the male Aryan ideal — the ‘tall statured, lean built man’, chiselled face, dressed in either traditional Germanic clothing, military uniforms or nude.

Riefenstahl’s film offers the audience a privileged and intimate view of the ritual and ceremony of National Socialism. For the duration of the film, ordinary people could feel like the protagonists of Nazism, in control of Germany’s bright future (Chornyi, 2019). The sequence which begins with Hitler ‘performing the nation’ shifts to the grandeur of the indoor party hall creating a mesmerising political atmosphere. Every gesture, expression and intonation are meticulously directed. In one moment, Hitler is amiable, joking and laughing with his followers. In the next, he is distracted, so lost in the urgent responsibilities of governance that he is seemingly unaware of the enraptured chanting as he glances over his notes (Riefenstahl, 1935, 00:01:35).

Hitler is always captured from a low angle, towering above the crowd in the stands (Riefenstahl, 1935, 00:01:09). This cinematic technique has multiple layers of meaning and emotional impact, both within the context of Nazi ideology and in terms of filmmaking techniques that continue to be used in films today. The low-angle shots place the camera below Hitler to magnify his presence and create a sense of dominance. This reinforces the idea that Hitler is not just a political leader but a supreme authority figure, positioning him as someone who is both infallible and transcendent.

While viewers are called to feel part of National Socialism, they are also reminded of the strong leader who guides and protects them. Psychotherapist Yvonne Karow describes this as a ‘cult of self-extinction’ (kultische Selbstauslöschung), a feeling of belonging exclusively to the movement bred enthusiasm for Nazism and fervent devotion to their Führer (Karow, 1999, p. 78).

The ‘cult of self-extinction’ highlights a critical aspect of the film’s propaganda: the way in which it fosters a sense of self-effacement among viewers, encouraging them to merge their identities with the movement and Führer. Individuals are not simply invited to admire or follow Hitler — they are encouraged to lose themselves in the collective experience of National Socialism. The idea of self-extinction suggests that, in fully embracing Nazism, the individual becomes subsumed within a larger, more powerful collective identity. For example, Hitler (1933) stated in one of his speeches:

When someone says, ‘You’re a dreamer’, I can only answer ‘You idiot…. If I weren’t a dreamer, where would we be today? I’ve always believed in Germany. You said I was a dreamer. I’ve always believed in the rise of the Reich. You said I was a fool. I’ve always believed in our return to power. You said I was mad. I’ve always believed in an end to poverty! You said that was utopian! Who was right? You or me?! I was right!

This quote reflects several key aspects of his political rhetoric where he positions himself as a visionary and invites the crowd to respond accordingly. Each time he stopped to catch his breath, the applause would intensify and heighten. Hitler himself believed in the power of speech to move and motivate groups of people (Hitler, 1925). In this way:

… all great movements are popular movements, volcanic eruptions of human passions and emotional sentiments, stirred either by the cruel Goddess of Distress or by the firebrand of the word hurled among the masses (Hitler, 1925, p. 107).

Hitler’s passionate proclamations from stages and balconies noticeably stirred the same passion within many citizens (Musolff, 2010).

The Nazis created an atmosphere of thrill and eruption to captivate the audience and provide an overwhelming sense of belonging. Third Reich propaganda targeted the personal and internal experience of the individual and the group. Goebbels himself believed propaganda’s task was to mobilise people in service of the Nazi worldview (Paxton, 2004). For Goebbels, propagandists needed to use words and images to reflect what audiences felt in their hearts (Paxton, 2004). The audience was instructed to become engulfed in a realm of unity, excitement, and anticipation in a series of close-ups and long shorts of adoring crowds. This would be achieved by targeting the spirit and the mind of nationalist groups to evoke feelings of rapture, enthrallment and even ‘transcendence’ — the feeling of being more than just oneself. The visionary transcendence aspect of Nazism was part of its appeal, inspiring people who felt ordinary and whose upbringing was largely religious. The ‘Rausch’ initiated by the mass rallies and Hitler’s speeches served to achieve an ‘instinctive’ connection to the regime. According to Hitler, the Volk members or Volksgenossen required a specific rapture to believe in the promise of a prosperous German future (Kilmo, 2004).

Building on the notion of transcendent unity, the opening scene of Triumph of the Will further elevates Hitler’s status, positioning him not only as a leader but as a near-mythical figure, whose presence looms over the German nation (Riefenstahl, 1935, 00:03:03). The film plays on heroic motifs, where Hitler takes on the charisma of a Messiah figure, he appears to the audience as an untouchable representation of ancient Germanic myths (Shirer, 1941). The presentation of National Socialism as a political religion was a predominant theme that would be explored in all forms of propaganda. Cultural historian Piers Brendon deemed propaganda the ‘gospel’ of National Socialism (O’Shaughnessy, 2009). This projection of Hitler’s power and charisma is raised to a form of ‘Rausch’ as the film begins the audience views Hitler descending from the clouds of heaven, down to the terrestrial bounds of Nuremberg. Hitler emerges as a figure both grounded and otherworldly, embodying a transitional leader at the heart of the political religion that is National Socialism (Chornyi, 2019). The effect is a collective experience of fanaticism, enthusiasm, reverence, and in some cases, violence that is associated with mass gatherings or rallies.

Conservative and Nationalist Groups, SS and SA members and members of Volksgemeinschaft shared in the religious image Hitler cultivated of himself as the saviour of the earth (Fest & Herrendoerfer, 1977). The messianic, pseudo-religious aspects of Nazism have been the focus of historical enquiry in recent years (Evans, 2006). With their distinctive uniforms and rituals, the infamous salute paying homage to Hitler, National Socialism perhaps embodied a new denomination of worship as much as a new political ideology (Hastings, 2008). National Socialism offered elatedness, vivacity and extraordinary forces of emotion and belonging. As with any religion, while Hitler offered protection and reassurance, this relationship expected devotion and loyalty in return.

The portrayal of Hitler as a paternal protector and benevolent leader is deeply linked to the emotional exploitation central to Nazi propaganda. Hitler’s role as a protector is portrayed in a close-up shot of him holding a young girl’s hand, her mother standing proudly beside them to convey his paternalistic leadership (Hastings, 2008). The audience is encouraged to feel comforted, to know their own needs and the needs of the ‘Fatherland’ would be taken care of by their benevolent Führer. Projecting Hitler’s nurturing side positioned him as trustworthy and dependable. The fatherly imagery worked to soothe, pacify and reassure viewers as Hitler cared for them as he would care for his own children, although he had no children and was not married. Hitler was often photographed embracing young children, while appreciative mothers gazed in admiration (Shapira, 2018, p. 182).

It appears that the Nazis also tried to portray Hitler as an object of sexual desire for women. While he was not a ‘family man’ in reality, this status was presented as a form of sacrifice for the nation. By framing his personal life as a conscious choice to forgo familial ties, the regime crafted an image of Hitler as wholly dedicated to the German people, positioning him as a selfless leader devoted to the greater good of the nation rather than to personal comforts or ambitions. This portrayal allowed the Nazis to evoke a sense of longing and admiration among women, who were encouraged to see him not just as a political figure but as a protector of the nation — a man who had chosen to devote his life to their safety and well-being. While Hitler’s success in the 1933 election has been attributed to his sexual appeal among women, women did not comprise the majority of Nazi voters (Reich, 1936. Hamilton, 1982). Many Germans were called to feel like protagonists of Nazism — each involved in their own set of duties.

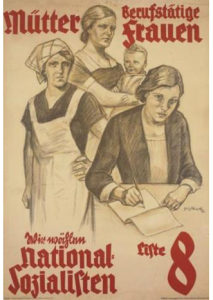

The image of womanly ideals promoted by Nazism was defined by the expression ‘Kinder, Küche, Kirche’ (children, kitchen, church) (Bock, 1984) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Felix Albrecht, Mütter, berufstätige Frauen – wir wählen National-Sozialisten Liste 8, 1932. Poster. Source: Library of Congress, digital image. LC-DIG-ppmsca-21994.

German women were recognised by Nazism but only as mothers and wives (Gupta, 2002). The cult of motherhood that would ensure the support of women was in part through an emotional connection to Hitler’s attractive and protective pretence. Hitler as a paternal figure also offered relief to parents by reassuring the safety of German children. The authoritarian style of parenting that was common in early 20th century Germany — while fostering warmth and love — also demanded devotion and obedience (Gay, 1993). By showing Hitler in close, nurturing interactions, such as holding a child’s hand or being surrounded by admiring mothers, propaganda aimed to evoke feelings of comfort, safety and trust among viewers. The Nazi regime not only elicited admiration and trust but also a sense of duty among all Germans — adults and children alike. The emotional triggers present in these portrayals of Hitler tied personal identities and aspirations to the larger nationalist vision, placing Hitler at the emotional and ideological epicentre of Nazi Germany.

Olympia

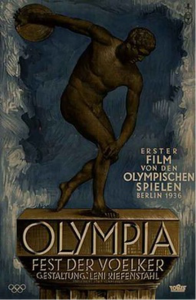

Figure 3: Olympia: Courtesy of the Deutsches Bundesarchiv.

Triumph of the Will and Olympia serve as powerful visual manifestations of Nazi ideology, both using innovative cinematic techniques to glorify national identity and showcase the spectacle of public gatherings. By manipulating visual and emotional cues, such as the grandiose portrayal of Hitler and the ecstatic responses of the crowds, these films aimed to evoke deep emotional connections with the audience, aligning them with the regime’s vision of national renewal and collective destiny. Also directed by Leni Riefenstahl (1938), Olympia posed as a documentary of the 1936 Summer Olympics and was released in two parts. Firstly, Olympia 1: Teil—Fest der Völker (Festival of Nations) portrays a historical account of the Olympic games, depicting ancient game traditions in Olympia. Olympia 2: Teil—Fest der Schönheit (Festival of Beauty) features track and field events of the 1936 Berlin Games. The documentary narrative structure was designed to give the impression of being informative and unbiased. On the surface, it appears to chronicle the achievements of athletes all over the world. However, scrutinising Riefenstahl’s cinematic techniques reveals sources of emotional exploitation in the promotion of the Nazi worldview.

Olympia was the first film documentary of the Olympics to be produced, and Germans were proud of the national technological prowess that the film projected (Graham, 1986). The film incorporated two pivotal components: sound and editing which were still uncommon in documentaries of the time. The novelty of sound significantly enhanced the emotional intensity of the film, turning it into a sensory experience of thrill and exhilaration. In the film’s depiction of the opening ceremonies, Riefenstahl’s narration provides a rich context, describing the grandeur and significance of the event. This commentary not only sets the stage for the spectacle but also evokes a sense of awe and anticipation among viewers. The narration emphasises themes of unity and strength, reinforcing the emotional impact of the scenes being shown.

Like Triumph of the Will, Part One opens with the transcendence through smoke-filled ruins and statues of ancient Greece. The statues soon transfigure into naked dancers and professional athletes, and the audience is taken through time before arriving at the torch relay of the Olympic cauldron in Berlin (Riefenstahl, 1938, 00:03:12). The film paces through an array of events in and out of the stadium, accompanied by enthusiastic commentary and electrifying music (Riefenstahl, 1938, 00:55:20). The momentum in these scenes is never stagnant, and the audience becomes situated in an atmosphere of grandeur and extravagance to stir emotions of awe and astonishment. Olympia was used to promote National Socialism as truly ground-breaking. This worked to assert Germany as the world leader with its advanced production and state-of-the-art technology.

It is important to appreciate the considerable and often demanding task of sound and film editing during this time. In 1936, directors did not have soundproofed cameras, zoom lenses or computer polishing to simplify the task of editing (Hilton, 2000). During the sequences featuring athletic competitions, the music intensifies to match the physical exertion and drama of the events. For example, during the track and field events, the score features powerful, musical motifs that build excitement as athletes push their limits. This musical accompaniment creates a thrilling atmosphere, engaging the audience and heightening their emotional investment in the athletes’ performances. The use of advanced motion picture techniques such as extreme close-ups, smash cuts and tracking shots in the movie was well beyond its time and truly engaging. From ensuring fluent transitions between scenes to creating artificial sunlight, Riefenstahl’s cinematography distinguished the film from typical documentaries of this time (Berg-Pan, 1980). Viewers today can become immersed in an atmosphere so compelling that one feels as though they are a living part of the 1936 games.

Nevertheless, the film is hardly concerned with the competitiveness of the Olympics and refrains from building anticipation for the winner of each event (Hilton, 1982). The primary focus was to render each event uniquely cinematic (Barber, 2016). This aesthetic approach turned an ordinary record of diving into an abstract and mesmerising aerial ballet through slow motion and crosscuts. One segment is reversed so that the diver emerges out of the water and into the air (Riefenstahl, 1938). The film did not merely chronicle Olympic events, it evoked and idealised the glory Germany strived for and presented the aesthetic vision of Nazi Germany in its most polished form.

Riefenstahl distinctly captured each event to ensure that all movements remained equally compelling. Olympia has been described as ‘a film within a film’ that became the archetypal emblem of achievement and endurance (Downing, 1988). The imaginative use of distorted bodily shadows, intertwined with shots of leg muscles pulsing and feet beating against the track, invited viewers to notice their own bodily sensations, feeling the strength flowing within themselves. The comparison with the lack of previous films of the Olympics is worthy of mention — the Olympics of 1928 and 1932 took place in the era of silent films, so much less was possible. It is important to stress the significance of such editing when soundtracks are very new. As the athletes began to feel the exhaustion draining from their bodies, each frame provided a surplus of energy and an admirable, perpetual drive (Riefenstahl, 1938, 01:46:00). Thereby, Olympia epitomises what Graham (1986) called ‘sociological’ propaganda.

Olympia navigated the celebration of Aryan ideals while also showcasing athletes from diverse backgrounds, notably Jesse Owens, through a complex portrayal of athletic excellence that transcended racial boundaries. The film did not blatantly indoctrinate viewers with the principles of National Socialism, but rather, promoted an embodied, innate and racialised image of ethnic Germans. The audience was called on to engage in a captivating documentary film featuring admirable feats performed by athletes across the globe. By including black American athlete Jesse Owens, Olympia presented a contradictory narrative: while the overarching theme promoted Aryanism, the film simultaneously acknowledged that greatness in athletics could emerge from anywhere, even outside the Aryan ideal. This duality reflects a key tension — where ideology clashed with the undeniable reality of exceptional talent, regardless of race. Ultimately, Olympia celebrated athleticism as a shared human endeavour, albeit within a framework that still sought to reinforce the Nazi ideology of racial hierarchy. Viewers of other nations could be delighted to see their favoured athletes being promoted. Such positive feelings about the film would expectantly extend to the creators of the film — and to National Socialism. Olympia gave Nazism widespread exposure and recognition across other nations. This would pave the way for Nazi Germany to emerge as the leading ‘Great Power’.

Olympic imagery was used to promote Nazi ideology disguised in the form of entertainment. Riefenstahl captured the competition between German competitor, Lutz Long, and the American, Jesse Owens. Owens’ triumphs, having won four gold medals, were portrayed in a manner that highlighted his extraordinary talent and determination (Riefenstahl, 1938). Riefenstahl captured Owen’s races with dynamic cinematography, showcasing the excitement and intensity of his performances. This portrayal not only celebrated his achievements but also positioned him as a symbol of universal athletic excellence. The elements of drama and tension are effectively heightened through acute, slow-motion camera work and rapid medium-shots of audience reactions (Riefenstahl, 1938). Significantly, Hitler is excluded, as he seldom appeared to applaud non-German athletes, and certainly not people of colour.

The camera was not concerned with record-breaking feats as much as the athletes themselves. This film promotes a striking vision of the superiority of the ‘Aryan’ race, a mythical invention of the Nazis that epitomised the ideal German. According to the hierarchy of National Socialism, the Aryans were the superior ‘master’ race, destined for world domination, later manifested through the ambition to annihilate those deemed their racial enemies. Slow motion was applied to German athletes, depicting their bodies as superhuman, despite the outcome of the race. The quintessential Aryan attributes align closely with the Olympic games: physical sublimity, a heroic, ancient past and the division of the world into separate, competing countries. Despite this, German athlete Lutz Long lost the long jump event to Jesse Owens, who delivered a historic victory that highlighted the racial tensions of the time (Riefenstahl, 1938).

Riefenstahl’s choice of shots, music, and editing in Olympia aimed for a wide range of emotional responses, intertwining aesthetic beauty with deeply political messages (Berg-Pan, 1980). Part Two opens with an extreme close-up of a bird’s wing, as well as a trembling drop of water on a web, and of white, muscular, male figures (Riefenstahl, 1938, 00:01:20). The combination of sensual and visual techniques promoted Nazi ideology as seductive and beautiful. Such avant-garde sequences served to publicise Nazism as technologically advanced, the white, sculptured bodies epitomising the inherent characteristics of the German ‘master race.’ The emotional power of these images was amplified by the accompanying music, which built a rhythmic, almost hypnotic tension, aligning the audience’s emotional state with the visual glorification of the human body. This aesthetic experience was designed to stir a sense of awe and transcendence, elevating the athletes’ performances into symbols of something greater: the ideal of a racially superior, harmonious, and technologically advanced nation. In this way, the aesthetic was not merely a backdrop to the events but a tool to emotionally engage the audience and align them with the ideological goals of the regime. The white, sculptured bodies of the athletes were carefully framed as the epitome of the German ‘master race,’ and through these visual and emotional cues, Riefenstahl sought to convey Nazism as not just a political force, but a cultural and emotional experience — something deeply beautiful, alluring, and worthy of reverence (Riefenstahl, 1938, 00:16:00).

Building on the emotional and aesthetic power that permeated the film, the final sequence intensifies this effect. Olympia ends with a crescendo; the diving sequence includes an elevation device mounted by the pool to warrant effortless movements. In slow motion, the divers appear from the sky above, defying the notion of gravity as they twist and twirl in the air (Riefenstahl, 1938, 01:20:00). Riefenstahl omitted commentary in this scene to ensure a mesmerising impact on its audience. Such carefully crafted filmic techniques were deployed to create an unprecedented experience of viewing documentaries. While some might have interpreted the film as a celebration of athleticism and unity, others could discern the underlying propaganda that aimed to promote Nazi ideology. The film was released in various cinemas outside Germany, including in countries like the United States and France, where it sparked both admiration for its artistic achievements and criticism for its political implications (Beyl, 2001).

The film celebrated athletic excellence as a reflection of national strength and superiority, showcasing German athletes prominently and emphasising their achievements in the context of national pride. However, the emotional impact of Olympia is not limited to its technical or aesthetic achievements; it is deeply intertwined with the reactions of both the athletes and Hitler himself. When the audience becomes mesmerised by the spectacle, the frame shifts to reveal Hitler cheering passionately from the stands when the Germans succeed or anxiously tapping his fingers on his uniformed knee when they falter (Riefenstahl, 1938). These candid intervals humanise Hitler, offering a rare glimpse of vulnerability that contrasts with his usual authoritative image. By placing these emotional moments in the context of the athletic competition, the film draws on a collective emotional experience, where Hitler’s anxiety and triumphs become an expression of their own. The emotional tension between athletic success and failure, as experienced by both the athletes and Hitler, underscores the stakes of the event: the affirmation of Nazi ideals through the display of physical and national strength. This interplay of emotion and aesthetic grandeur contributes to Olympia‘s power as a propaganda tool, emphasising not just athleticism but the emotional resonance of victory and the unity it was meant to symbolise for the Nazi regime.

Conclusion

There can be no doubt about the role of propaganda as a major contributor to the rise and success of Nazism in the 20th century. Third Reich propaganda targeted emotions linked with the desire for redemption and revenge, for belonging, dignity, and meaning, which have been identified in the scholarship as being more susceptible to manipulation. The Nazis exploited the existing fears and desperation surrounding Germany’s uncertain future to garner enthusiastic support, asserting that they deeply understood and shared in these struggles. Third Reich propaganda targeted nationalist groups, those disillusioned by Germany’s instability, German youth, anti-Semites and the politically naïve audiences of their propaganda messages.

Through the lens of the history of emotions, this article has analysed the emotional mechanisms at work in Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938), demonstrating how these films were not mere political tools but powerful emotional experiences. Riefenstahl’s use of aesthetic techniques — such as music, camera angles, and the idealised portrayal of athletes and leaders — served to evoke deep emotional responses that aligned viewers’ personal feelings with the Nazis’ ideological goals. By focusing on emotional dynamics, it becomes evident that propaganda became a catalyst for shaping national identity, fostering unity, and reinforcing the sense of strength and transcendence that Nazism promised. These emotional experiences were integral in creating a collective bond, ensuring that Nazi ideology became deeply embedded in the hearts and minds of many Germans.

This approach provides a new framework for understanding the psychological power of propaganda and its role in sustaining totalitarian regimes. The analysis underscores that propaganda was not just a political strategy but a cultural force that emotionally bonded individuals to the regime. This article focuses on two emotions targeted by Nazi propaganda: German humiliation through Dolchstoßlegende (‘stab in the back’ myth), and nationalism as an emotion, as conveyed in Triumph of the Will and Olympia. It highlights how the manipulation of pre-existing emotions — such as fear, hope, and pride — turned ordinary individuals into fervent supporters of a radical ideology. This article underscores how both films functioned not as just pieces of propaganda but as emotional experiences designed to solidify the loyalty of German citizens. Moreover, this emotional framework opens valuable avenues for future research, encouraging scholars to examine the emotional strategies employed in other political regimes and to explore how propaganda continues to shape public sentiment and collective consciousness, especially during times of political upheaval or social unrest. Understanding the emotional underpinnings of Nazi propaganda helps us recognise how potent emotions can be in shaping and manipulating public support for political movements, often with long-lasting and dangerous consequences.

Ultimately, the intimate relationship between propaganda and emotional manipulation was key to the success of the Nazi regime. By evoking powerful emotions tied to national pride, racial superiority, and collective unity, Nazi propaganda worked to generate a fanatical loyalty that extended beyond mere ideological persuasion — it became a force that infiltrated every aspect of life, shaping the political and social fabric of Germany in the 1930s and beyond. The interdisciplinary study of the history of emotions within political propaganda thus offers profound insights into the power of emotions as motivators for both support and complicity and how, in the case of Nazi Germany, this emotional manipulation contributed to the radicalisation of individuals and the horrific actions that followed.

References

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

Arendt, H. (2007). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil. Penguin.

Barber, N. (2016). How Leni Riefenstahl shaped the way we see the Olympics. BBC Culture. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160810-how-leni-riefenstahl-shaped-the-way-we-see-the-olympics

Barclay, K. (2020). The History of Emotions: A Student Guide to Methods and Sources. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Bavaj, R. (2014). Die Ambivalenz der Moderne im Nationalsozialismus: Eine Bilanz der Forschung. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Berg-Pan, R. (1980). Leni Riefenstahl. Twayne Publishers.

Beyl, W. (2001). Olympia: Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda triumph. The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 21(2), 153–171.

Bracher, K. D. (1970). The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism. Praeger Publishers.

Bock, G. (1984). When Biology became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany. Monthly Review Press.

Booth, A., et al., (2013.). Hormones and behaviour.

Bourdieu, P. (2017). Habitus. In Habitus: A sense of place (pp. 59-66). Routledge.

Chornyi, D. (2019). Leni Riefenstahl on her way to the Triumph of the Will.

Cull, N. J., Culbert, D., & Welch, D. (2003). Propaganda and mass persuasion: A historical encyclopedia, 1500 to the present (pp. 10–39). Bloomsbury 3PL.

Deutch, D., & Yanay, N. (2018). The politics of intimacy: Nazi and Hutu propaganda as case studies. Journal of Genocide Research, 18(1), 21–39.

Dimsdale, N. H., Horsewood, N., & Van Riel, A. (2006). Unemployment in Interwar Germany: An analysis of the labor market, 1927–1936. The Journal of Economic History, 66(3), 778-808.

Downing, T. (2017). Olympia. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Ellul, J. (1971). Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. Knopf.

Evans, R. J. (2006). Nazism, Christianity and political religion: A debate. Journal of Contemporary History, 42(1), 5–7.

Falk, A. (2006). Collective psychological processes in anti-Semitism. Jewish Political Studies Review, 37-55.

Fest, J., & Herrendoerfer, C. (1977). Hitler: A Career. Little, Brown.

Firth-Godbehere, R. (2021). A Human History of Emotion: How the Way We Feel Built the World We Know. Little, Brown Spark.

Finger, S., Boller, F., & Tyler, K. L. (Eds.). (2009). History of Neurology. Elsevier.

Gay, P. (1993). The Cultivation of Hatred: The Bourgeois Experience, Victoria to Freud. W.W. Norton & Company.

Goldhagen, D. J. (1997). Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. Vintage.

Graham, C. C. (2002). Leni Riefenstahl and Olympia (Filmmakers Series). The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Gupta, C. (2002). Politics of gender: Women in Nazi Germany. Economic and Political Weekly, 37(1), 38–44.

Hamilton, R. F. (1982). Who voted for Hitler? Princeton University Press.

Hastings, D. (2008). Nation, race, and religious identity in the early Nazi movement. Journal of Modern History, 80(2), 289–325.

Hinton, D. B. (2000). The Films of Leni Riefenstahl (No. 74). Scarecrow Press.

Hitler, A. (1999). Mein Kampf. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Hitler, A. (1929, March 15). Speech at Munich https://www.hitler-archive.com/speeches.php.

Hoffmann, H. (1996). The Triumph of Propaganda: Film and National Socialism, 1933–1945. Berghahn Books.

Hochschild, A. R. (2015). The Managed Heart. In Working in America (pp. 29-36). Routledge.

Kallis, A. (2005). Nazi propaganda and the Second World War. Palgrave Macmillan.

Karow, R. (1999). Deutsches Opfer: Die Zwangsarbeiter im Dritten Reich. Dietz Verlag.

Kershaw, I. (2002). Popular opinion and political dissent in the Third Reich: Bavaria 1933–1945. Clarendon Press.

Kilmo, J. (2004). Nazi discourses on ‘Rausch’ before and after 1945: Codes and emotions. Journal of Contemporary History, 39(4), 475–491.

Kracauer, S. (1947). From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German

Film. Princeton University Press.

Mazur, A. (1973). A cross-species comparison of status in small established groups. American Sociological Review, 513-530.

McLuhan, M. (1967). The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. City of Westminster/Penguin Books.

Musolff, A. (2010). Metaphor, Nation, and the Holocaust: The Concept of the Body Politic. Routledge.

O’Shaughnessy, N. (2009). Selling Hitler: Propaganda and the Nazi brand. Journal of Public Affairs, 9(1), 55–76.

Oliveira, T., Gouveia, M. J., & Oliveira, R. F. (2009). Testosterone responsiveness to winning and losing experiences in female soccer players. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(7), 1056-1064.

Paxton, R. O. (2004). The Anatomy of Fascism. Alfred A. Knopf.

Reddy, W. M. (2001). The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Redlich, F. (2002). Hitler: Diagnosis of a destructive prophet. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(6), 1066–1066-b. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1066-b.

Reich, W. (1936). The Sexual Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Riefenstahl, L. (1938). [film] Olympia: Part one: Festival of Nations [Olympia: Teil I – Fest der Völker].

Riefenstahl, L. (1938). [film] Olympia: Part two: Festival of Beauty [Teil II – Fest der Schönheit].

Riefenstahl, L. (1935). [film] Triumph of the Will [Triumph des Willens].

Rosenwein, B. H. (2015). Generations of Feeling: A History of Emotions, 600–1700. Cambridge University Press.

Sartre, J. (1944.). Anti-Semite and Jew [Réflexions sur la question juive, ‘Reflections on the Jewish Question].

Shapira, A. (2018, November 13). ‘The Führer’s child’: How Hitler came to embrace a girl with Jewish roots. The Washington Post.

Scheer, M. (2012). Are emotions a kind of practice (and is that what makes them have a history)? A Bourdieuian approach to understanding emotion. History and Theory, 51(2), 193–220. https://doi.org/.

Shirer, W. L. (2002). Berlin Diary: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent, 1934-1941. Taylor & Francis.

Sontag, S. (2001). Against Interpretation and Other Essays. Farrar Straus and Giroux.

Souverän. (1938.). One People, One Nation, One Leader [Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer] (2:35).

Steiner, E. T. (2007). The effect of competition on testosterone responses (UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations, No. 2190). University of Nevada, Las Vegas. https://doi.org/10.25669/qoft-0us7.

Taylor, P. M. (1995). Munitions of the Mind: A History of Propaganda from the Ancient World to the Present Era. Manchester University Press.

von Tunzelmann, A. (2012, June 14). The Shameful Legacy of the Olympic Games. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2012/jun/14/shameful-legacy-olympics-1936-berlin

Welch, D. (2004). Nazi propaganda and the Volksgemeinschaft: Constructing a people’s community. Journal of Contemporary History, 39(2), 213–218.

Winkel, R. V. (2003). Nazi Germany’s Fritz Hippler, 1909-2002. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 23(2), 91-99.

About the author

Stefani Deligiannis is a PhD candidate in the field of History from the School of Humanities and Communications Arts at Western Sydney University and a member of the Golden Key International Honour Society. Her research explores the comparative role of emotion in Nazi and Italian fascist propaganda. The project explores two related regimes that deployed propaganda as a central tool for building a mass following, with a particular focus on their treatment of emotion as a bio-cultural phenomenon.