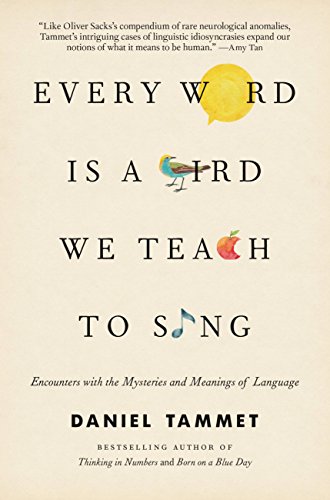

Tammet, Daniel - Every Word Is a Bird We Teach to Sing: Encounters with the Mysteries and Meanings of Language., New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2017. ISBN 978-0-316-35305-2 (pp. 273)

Reviewed by Amanda Tink - Western Sydney University

Ten years ago, I began attending Toastmasters, the worldwide public speaking organisation, imagining that the fortnightly practice would primarily benefit my speech preparation and delivery skills. A year later I won an award – not for speaking but for speech evaluation. The mission of Toastmasters is to develop its members’ communication skills. Being a club, however, its heartbeat is its growing membership. Thus, the other equally important goal of a speech evaluation is to ensure the person being evaluated feels encouraged to turn up for the next meeting. This means that the evaluator, regardless of how dull and disorganised a speech is, must find an accomplishment to acknowledge. Similarly, regardless of how brilliant a speech is, the evaluator must be able to explain why, and suggest an improvement. You might suppose, as I did, that I would be most grateful for this training at the end of yet another conference presentation that promised much more on paper than it delivered in practice but, more often, it is times like these – reviewing a book I love – that I draw most heavily on the many incisive suggestions of my evaluation mentors. Every Word is a Bird we Teach to Sing: Encounters with the Mysteries and Meanings of Language is not an academic book. It is the book I read to escape academia, but which always gently leads me back to it.

Daniel Tammet, an Englishman living in France, is a translator of upwards of ten languages and a writer of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Tammet’s first book was Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant (2006). Written when he was 26, Born on a Blue Day is his memoir of being ‘an autistic’ (sic, Tammet’s term for his experience). It chronicles his life growing up in England, a country with a language that felt foreign to him, and then living in Lithuania for a year, where he discovered his talent for teaching English.

Fast forward to 2017 and compact and differently focused accounts of these two periods of Tammet’s life are the first two chapters of this latest book. These chapters also articulate and encapsulate the three central premises of the book. Firstly, that all literature is translation – ‘a condensing, a sifting, a realignment of the author’s thought-world into words’ (17). Next, poetry, he says, is essential to language – ‘grammar and memory come from playing with words, rubbing them on the fingers and on the tongue, experiencing the various meanings they give off. Thirdly, textbooks are no substitute’ (34), and that, contrary to popular belief, autistic and author are not mutually exclusive – ‘Each [book written] taught me what my limits weren’t’ (17).

The book then develops these ideas through a series of chapters, each devoted to one of a variety of languages: Mexicano, Kikuyu, Icelandic, French. However, demonstrating a writers’ adaptability, and a disabled persons’ breadth of knowledge of people and communication, Tammet then traverses the following much more broadly:

- A history of Georges Perec and his famous novel A Void, written, as is the chapter, without the letter ‘twixt d and f’ (194).

- Language tests which, whether in school or medical settings, disadvantage people who are from a different culture or class than the person who devised the test.

- The Wycliffe Bible Translators who live with the communities for whom they translate, and thereby have their knowledge of both the bible and language transformed.

- The direct and spatial grammar of American Sign Language, some of the previous attempts to suppress it and its accompanying culture, and how it succeeds in situations where English does not.

There are three chapters to which I regularly return. The first is Tammet’s tribute to his mentor, the autistic poet Les Murray. The first half of this chapter contains a brief biography of Murray. As someone who is researching Murray and has therefore read a million of these, to not only know the details of Murray’s history, but to understand how they shaped his life, this is the only biography you need. The second half of this chapter contains the thinking behind some of Tammet’s translations of Murray’s poetry into French. Interweaving the two is the story of Tammet and Murray’s relationship, and this part documents the period during which Murray’s poetry gave Tammet the confidence to write to when they presented their work on stage together.

The second significant chapter explores the many effects that the telephone has had on how humans communicate. It is a history of a grammar through time and space, from the era when people had to be told that answering the phone did not require them to close their eyes, to the patterns of questions and reassuring noises that enliven and sustain our relationships.

The third important chapter explores human/computer communication, asking whether humans can identify who or what they are communicating with, and how that knowledge, or lack of knowledge, affects the interaction. Along the way the chapter presents compelling evidence that, while people from minoritised groups can accurately portray how people from the dominant culture interact, the reverse is not true without significant effort:

Reading papers and books and newspapers alone won’t do. You have to spend time, lots of time, in conversation with people who know from experience what they are talking about. (255)

These are the stories I escape into, not only for their information, but for their delight in language.

Finally, the number of academic purposes fulfilled by this book then gently leads me back to my own research. While many books will tell you which research, writing, and presentation methods you should use, this is a book that simply shows you how. Every chapter is essentially the same story as every other – Tammet wanted to learn about an aspect of language, he contacted an expert on it, and they gladly responded. The book does not read this way, however. It reads as a collection of meditations on language and communication. As such it both presents and enacts the message that there are at least fifteen ways to discover, describe, and discuss any topic.

Keeping my Toastmasters training in mind, it should be noted that this book’s strength is also its weakness. While the book discusses difficult political moments in language, it does not demonstrate any. The communication between Tammet and the many experts he consults is free of confusion, dishonesty, indecision, and disagreement. The presence of these would be informative because, as Tammet points out about computers, their ‘failure to say the right things does indeed seem telling’ (248). Some communication quandaries are solved by the perspective of time, or a fragment of poetry, or the kindness of strangers, as one repeatedly reads in this book. However, others are only solved when breakdowns or impasses in language are negotiated. Most importantly, as I believe Tammet could have demonstrated throughout this book, language enables this negotiation while retaining its versatility and beauty.

About the reviewer

Amanda Tink is a PhD candidate at Western Sydney University, researching the influence of impairment and disability on Henry Lawson, Les Murray, and Alan Marshall. She has been published in Southerly, Seizure, Wordgathering, and ArtsHub. She lives in front of her laptop and braille display with good coffee nearby.

Email: a.tink@westernsydney.edu.au

Twitter: @amandatink