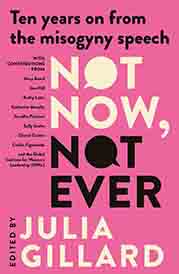

Julia Gillard - Not Now, Not Ever, Vintage Books: 2022 (pp. 238) ISBN978 0 143 77975 9

Reviewed by Jane Scerri - Western Sydney University

It is so heartening to recall Julia Gillard’s battle cry: “I will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny by this man (my emphasis). I will not!” I risk being accused of reverse sexism and perhaps putting readers off their lunch when I admit that the image that comes to mind when I think of “this man” is then prime minister Tony Abbott on the front page of some tabloid sporting his signature smirk and budgie smugglers. One can only imagine the quaking that occurred in his nether regions on that fateful (for him) day in October when Gillard took to the despatch box in the House of Representatives to deliver a response to a parliamentary motion. The response, which became known as “the misogyny speech”, gained national and worldwide traction and wiped the smirk from his face. Since then, many political women, including former Liberal staffers Brittany Higgins and Rachelle Miller, former Liberal MP Julia Banks and Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate, have embraced a broader pushback against members of the political class, in particular another former PM Scott Morrison. The election in 2022 of a new Labor government and loss of many previously blue ribbon Liberal seats to independent female candidates (labelled ‘the Teals’[1]), was partly seen as a reaction to Morrison’s tin-eared ‘woman problem’ (Crabb, 2022).

As I read this fabulous group of essays that Gillard has put together to commemorate the tenth anniversary of her speech, it struck me just how much she had to deal with during her time in office. Not only from “this man” but from misogynists in general – both as a ‘woman’ and as our first female prime minister. The book is a handy history of the last ten years of feminism, its progress, and its backflips, which thankfully, so far in this country hasn’t – as has happened in the US – included restrictions on the availability and legality of abortion – one of the most draconian backward steps for feminism and women in recent history.

Much of the gender-focused abuse directed at Gillard, for example, the poorly conceived ABC sitcom At Home with Julia (2011) – which was met with mixed reviews and was critiqued for focusing almost exclusively on her personal life, and for just not being funny – she took, like a good Aussie, in her stride. Gillard’s new book makes one think about the very notion of being a “good sport” and how this concept, with its own inherent set of sexist connotations, is one that has become almost antiquated in the current more atavistic and less egalitarian Australian cultural climate.

While reading the essays it becomes apparent that during Julia Gillard’s time in office, she was criticised, not only for not being the right kind of woman (aka, a mother), but also for not being the right kind of looking woman (whatever that is?). Kathy Lette reminds us in her essay that in 2007, Liberal Senator Bill Heffernan claimed Julia Gillard was “deliberately barren”, illuminating that, not unlike women in the Middle Ages who, suspected of being witches, were thrown in the water to see if they would drown. As a “childless leader”, Gillard was damned both ways: if she pursued a career and remained childless, no matter how qualified or able she was at her chosen profession, she was deemed potentially unreliable in that she may fall pregnant. And if she didn’t, by remaining “barren”, she was considered not to be a “proper” woman.[2] This was the ultimate misogyny – no man has ever had a high office challenged for not being a father.

Mary Beard’s essay on the history of misogyny contextualises the problem, noting that:

… the world’s museums and art galleries are full of the long history of misogyny, in word and image … Put simply art and literature are full of women being put down, dismembered, blamed, praised for knowing (their subservient) place, silenced and raped (72).

The challenge as Beard sees it is to subvert these culturally inscribed images, which is what Not Now, Not Ever does.

The tone of the tome is immediately rebellious and unapologetic, which makes perfect sense: by the time Gillard made the misogyny speech, she’d had a complete gutful! Also, it is refreshing as rebellion seems to be missing in much of modern discourse, replaced so often now by fumblingly self-conscious “genderless” language that focuses more on being inoffensive than meaningful.

Journalist Katherine Murphy discusses Aaron Patrick’s resistance to the:

… [a]ngry coverage that often strayed into unapologetic activism (coming) forth from a new female media leadership (37).

Murphy notes that Patrick’s concern with “all these angry women” is a kind of acknowledgement, a tonal shift that suggested women in the media had come of age, and were here to stay. Murphy also refers to the progress of feminism, (though she neglects to cite feminist historian Jill Julius Matthews (1984) on this), and relays how progress is generally two steps forward, one step sideways, one step back.[3] What has changed categorically since Gillard’s speech, Murphy claims, is that we have achieved “cultural change”.

Aleida Mendes Borges’ essay on intersectionality is poignant, and a reminder of how class and race cannot be considered in isolation, or as separate from feminism. She cites a sad, but funny, personal anecdote detailing how endemic racism and classism are, and how they intersect. When travelling in Brazil she is asked to go to a man’s hotel room, and though she is shocked, she politely declines and keeps walking. He then asks “Is that not what you Brazilian women want? To sleep with white tourists from Europe.” Borges thinks she should “give him a lecture on everything that is wrong with what he just said”, but instead swiftly remarks that she “is not Brazilian”. The man then “transforms into a completely different person” apologises and admits he should not have asked that. By way of explanation, he adds that: “He thought [she] was Brazilian” (80).

Borges (82-83) then addresses the history of female black bodies and how they have been considered property, for:

… even though white women’s bodies were also objectified and subjugated during the centuries of the slave trade, white women benefited from the structural protection of white supremacy.

This chapter is a stark reminder of how class and race differences intersect with gender and are implicit in understanding feminism, and why black women are often ambivalent to white feminism. It also details how significant poverty, with its implicit lack of access to social and health services, especially safe abortion, is for women trying to escape misogyny and violence.

In chapter six, Michelle K. Ryan and Miriam K. Zehnter consider the tools of patriarchy and denote sexism in four ways: traditional, hostile, modern, and “belief in sexism shift”. Traditional relies on the “good mother” myths, and “functions like a mould, trying to preserve the shape of the gendered status quo as it was” (104) – hostile sexism is more directed at those women considered to have transgressed traditional lines.

Abusive language such as ‘ditch the witch’ and ‘a man’s bitch’ quoted in the misogyny speech is an overt example of hostile sexism (105).

“Modern sexism” – essentially the denial that sexism and misogyny continue to exist – as Ryan and Zehnter explain, is problematic because it “places the blame for continuing gender inequalities on women themselves” (114). The newest kind of sexism outlined in this essay – the “belief in sexism shift” – purports that men are now disproportionately disadvantaged and that women have been given unfair advantages. Extremist groups such as U.S far-right group the Proud Boys and “incels” (short for involuntary celibates – which means they want sex but can’t get it; in case you are unfamiliar with the concerns of this niche men’s group), tend to uphold this “philosophy”. The extent of the whining vitriol on Twitter in response to Dan Andrews’s election pledge to provide free tampons and pads to alleviate period poverty speaks to the fact that this “sexism shift” is indeed very much alive and well in Australia today. [4]

Jess Hill’s essay on violence in the family and coercive control strikes a chilling chord: “With the exception of the police and the military, the family is perhaps the most violent social group, and the home the most violent setting in our society” (130). Hill explains how insidiously and simply, coercive control works and elaborates on how humiliation is a trigger for an even more stringent tightening of control for those who resort to it.[5] She cites the psychoanalyst Eric Fromm’s explanation of the desire for such control as being, “[t]he passion to have absolute and unrestricted power over a human being” and that it manifests as the “transformation of impotence into omnipotence” (137). This chapter discusses how gender stereotyping limits both sexes, and Hill’s concluding paragraph delineates the need to “define … the system that entraps both sexes …” (141).

The book ends on a high note, with Julia interviewing three young feminists. She discusses the changing tide, evoking the Tik Tok video of a sassy young woman mouthing the words to the misogyny speech as she is putting on make-up as she gets ready to go out, with the words to the Doja Cat song “I’m a bitch, I’m a boss” running in the background. After presenting the views of the three young feminists, Chanel Contos, Caitlin Figueiredo and Sally Scales, Gillard concludes that there is a core of agreement between these young activists – “that feminism is about true equality ¾ but such a diversity of context and views about what gets prioritised. Being prepared to educate and having the courage to challenge are common themes.” Gillard then asks herself, “whether that is any different from the past” and finds “herself thinking no, it is not. However, today’s reality is different to any other time in history, with much more understanding of the way, gender, race, and other forms of discrimination intersect” (200).

This summary quote on the state of play of modern feminism speaks to both the content and strength of the collection within Not Now, Not Ever. It teases out what has changed, and what still needs to, and gives up close and personal accounts of how a range of mostly Australian, feminists, including journalists, politicians, activists, writers, and historians have tracked the progress of women and their reception since 2011. In this way, the book is a terrific touchstone on the progress of feminism in general, and more particularly, how recent social and cultural events and new women’s activism have helped to deconstruct misogyny in Australia over the last decade.

Works Cited

Cat, D. (2020). ‘I’m a Bitch I’m a Boss’. Birds of Prey, Atlanta Records.

Champagne, I. (2022, November 16). Men on Twitter are losing their shit over Andrews’ free tampon announcement Crikey. https://www.crikey.com.au/2022/11/16/dan-andrews-free-tampons-men-twitter/.

Crabb, A. (2022, May 22). The lost women. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-23/election-2022-morrison-women-vote/101089978.

Kalowski, R., Lee, D., Quail, G. (2011). At Home with Julia. Quail Television.

Matthews, J.J. (1984). Good and mad women: The historical construction of femininity in twentieth-century Australia. Allen & Unwin.

NSW Government (2022, October 19). Coercive control bill passes the Lower House [Media Release] https://www.nsw.gov.au/media-releases/coercive-control-bill-passes-lower-house.

Summers, A. (2013). The misogyny factor. NewSouth Publishing.

Wahlquist, C. (2022, May 23). Teal independents: Who are they and how did they upend Australia’s election. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/may/23/teal-independents-who-are-they-how-did-they-upend-australia-election.

About the reviewer

Dr Jane Scerri is a writer, literary critic and casual academic in Arts and Communications at Western Sydney University. Her interests are feminism, single motherhood as a site for feminist reimagination, and contemporary Australian literature. She has published poems, short stories, journal articles and literary criticism and is currently working on her second novel.

Email: jane.scerri@westernsydney.edu.au

[1] See: ‘Teal independents: who are they and how did they upend Australia’s election.’ https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/may/23/teal-independents-who-are-they-how-did-they-upend-australia-election

[2] Liberal Senator Bill Heffernan, referring to fecundity in relation to Julia Gillard, said, “anyone who chooses to deliberately remain barren…They’ve got no idea what life is about” (Summers, 2013, p. 121).

[3] “Across the century, the feminine dance is curiously constant: one step forward, one step sideways, one step back” (Matthews, 1984, p. 199).

[4] See Champaign (2022) on the reaction to Victorian premier Andrews’ proposal to make tampons free

[5] The coercive control bill passed the lower house in N.S.W. on Wednesday 16th November 2022.

https://www.nsw.gov.au/media-releases/coercive-control-bill-passes-lower-house