New media electioneering in the 2013 Australian federal election

Peter John Chen

University of Sydney (Australia)

Abstract 1

This article provides an overview of the use of new media by Australian political parties and individual candidates in the 2013 federal election. It updates research undertaken over the past decade on institutional responses to new technological affordances in electoral campaigning. Using content analysis, interview and third-party data, the paper demonstrates that the major political parties in Australia have increased their use of new media in their overall communications mix, with a heightened focus on advertising in social media, the integration of various online channels, and through creative fundraising strategies. It is argued that the major parties considerably professionalised their management of new media for the 2013 campaign, and the lessons from this election will endure into future electoral contests. The data from the content analysis suggests that the online visibility of minor parties and individual candidates appears to be declining, outside of gaffs, and the novelty reporting of ‘quirky’ candidates. The exception to this remains the Australian Greens, because of their natural affinity with voters most likely to be heavy users of new media. The increasing sophistication of data-driven, targeted advertising further reinforces the capacity of the two major Australian parties to dominate the new media environment due to their disproportionate access to electoral resources. This appears to provide further, but not unambiguous, evidence of the ‘normalisation hypothesis’ of institutional new media adoption in Australia.

Introduction

The impact and use of new media technologies on political campaigns in Australia has been the subject of attention for well over a decade. Initial research in this area undertaken by Gibson (2002; 2003) focused on questions of ‘democratisation’ or ‘normalisation’ in the adoption of information and communication technology by parties and candidates. The research has focused on the extent to which different electoral contexts drive the adoption of new forms of communication for competitive purposes, and the implications this has on the visibility of different candidates and policies in the political-media environment. Simply put, this research tended to ask if newly adopted technologies increase the visibility and competitiveness of independents and minor parties in Australian elections (democratisation), or whether major parties are able to better leverage their structural and economic resources to recreate their political advantage (normalisation).

While this is essentially a question of the democratic character of elections in this country, 2 it also reflects a longer history of domestic research on the way party organisations have responded to technological change to increase competitiveness (Young, 2003, pp. 109-10), and the impact of different technologies on the internal distribution of political power within party organisations (van Onselen & van Onselen, 2008). Further work in this area has looked at patterns of adoption and use of new media over time by party organisations and individual political elites (Chen, 2005; Chen & Walsh, 2010; Gibson & Cantijoch, 2011; Macnamara & Kenning, 2011; Chen, 2012; Chen 2013), cross-national comparisons (Gibson, et al., 2003; Chen, 2010), and the relationship between online electioneering and electoral success (Gibson & McAllister, 2011). This body of research reflects a specific and focused interest on the institutional responses by political parties and political elites to the array of emerging technologies, their adoption and application within the specific political sub-discipline of elections and electoral campaigns. 3

From this work undertaken in Australia to date, we can see that the use of new media has moved from a novelty employed by parties and candidates (Gibson & McAllister, 2008, pp. 35-7) to becoming an important – if still secondary – aspect of parties’ political communication toolset in the electoral process. This seriousness is seen in the professionalisation of the management of new media channels and messaging by parties, higher levels of expenditure on new media campaigns, increased use of inter-jurisdictional knowledge transfer and learning, and heightened risk management by political organisations. The study of these changes over time is a good case example of the normalisation and domestication of wholly new communication technologies in the Australian polity (Gibson & McAllister, 2011).

Following this tradition of research, this article describes the way new media have been employed as a tactical tool for electioneering by political parties and candidates. It notes changes between the 2013 election and previous contests, and the relative significance of new media in the 2013 campaign. It is argued that, while the comparatively pre-determined nature of the election made the role of new media appear considerably less important than in previous electoral cycles, higher investment of resources were employed and a greater sophistication of application can be identified. Overall, following the question asked by Gibson and Cantijoch (2011), the article concludes that new media finally ‘arrived’ in the 2013 campaign as a core element of electoral campaigning. The deployment of new media in the 2013 election demonstrates considerable sophistication by parties and some candidates, with tangible impacts on the reach of parties’ and candidates’ messages and capacity to generate and deploy resources. Innovations in political organisations facilitate increased lesson drawing over previous electoral cycles, which will see tactical and strategic lessons carry through into future, more competitive electoral races.

Methods

Two primary research methods were employed for this analysis: personal interviews with key party personnel and a content analysis of online content produced by individual lower-house candidates. In addition, a considerable amount of secondary data from web metrics providers was aggregated to provide insight into the use and impact of party media strategies. This follows a research strategy established for the 2004 election, and reproduced in 2007, and 2010. This method has also been used for provincial and national elections in Canada and New Zealand (Chen, 2010).

Interviews were undertaken with key digital campaign management staff in the Australian Labor Party (ALP) (Skye Laris, Director of Digital Communications, Organising & Campaigns, ALP, July 23, 2013) and the Australian Greens (Rosanne Bersten, National Digital Communications Coordinator, Australian Greens, August 2, 2013). A requested interview with the Liberal Party of Australia could not be obtained. Interviews were undertaken in person and by telephone, and digitally recorded for transcription and analysis.

The content analysis method employed focused on identifying and comparing the use of new media by individual candidates in the election. This recognises the need to pay greater attention to the wide range of online tools and social media, not simply candidate website content and functionality. This includes their characteristics as communications channels, their inbuilt biases, and audiences and the relationships between different channels of communication. The aim of this approach was to (a) identify the number of different channels or means of self-representation online (‘points of presence’) candidates’ maintained across a range of channels and sub-media; 4 and (b) determine the extent to which each ‘point of presence’ had been utilised by candidates.

Following random sampling of the population of candidates, their online presence was quantified to determine their use of various digital media. Search tools employed to identify candidates’ points of presence included Google (market leader) search engine, search functions of the social networking/content hosting services studied (Facebook, YouTube, Linkedin, and Twitter); and party website search engines to identify and classify candidate’s entries within the website (‘mini-sites’).

Data interpretation was undertaken using two constructs:

- Plotting depth-width measures: The creation of the depth and width measures was a deliberate attempt to delineate between the increasing ability to have a large number of points of presence and the investment of time and effort to ‘populate’ each (e.g. to fill a website or content sharing service with content and/or functionality, or to collect nodes and/or subscriptions in social networking and content syndication services); and

- Intensity: A single compound number was generated to measure the absolute ‘intensity’ of the candidate’s online presence. This measure was useful in determining correlations.

The sample size of the candidate content analysis was 13.4% of an N of 1,188 individuals, or 13.3% of an N of 150 electorates. This is the only regular known Australia study of candidates (as opposed to studies of incumbents).

New media on the campaign trail

The use of new media by major parties organisations, and candidates as individual campaigners, has intensified over previous Australian election cycles. While this may be expected, previous research has demonstrated that technology adoption by candidates and parties is not strictly linear, nor progressive over time. This is due to a range of factors including leadership choices, situational capacity and resources. Different actors have different capacity to acquire technology, personnel and expertise. In addition, the political utility (reach, affordances offered, and social meaning) of various channels (internet sub-media) shifts over time, either due to changing levels of popularity (such as the eclipse of MySpace as the primary social networking service (SNS) used by Australians) or because of socio-technical changes to users’ consumption habits (such as the decline of feed aggregators in favour of social filtering and referral through social media networks). Thus, in addition to considering the way the logic of political competition shaped media choices, when considering the use of new media – with its rich plasticity – it is important to link behaviour with the underlying competitive logic of the current media environment (Krotz, 2008). These factors shape the strategic choices made by key actors when considering how new media is deployed by electoral actors and media organisations.

The parties: Get big or get out

The Australian electoral environment is dominated by two tendencies driven by cultural norms and structural incentives: an increasingly presidential, party-centric model of electoral competition (Costar, 2012), and an emphasis on the two-party system as a primary definer (Barker, 2003) of electoral attention by voters, citizen journalists and commentators, and news organisations. Thus, this section focuses largely on the two major party groupings, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the Liberal-National Coalition (‘the Coalition’) with commentary on minor parties where relevant and instructive.

Planning a new media election campaign

In preparation for the 2013 campaign, the established political parties undertook considerable strategic and tactical planning in the way they intended to deploy new media channels. This is demonstrated both in the behaviours of these parties – through careful co-ordination of messages across different channels (online and off) and attention to the active nature of online audiences as co-creators of content and referents for their social networks. In addition, we witnessed the escalation of new media managers within their campaign teams from peripheral to more central actors (S. Laris, personal communication, July 23, 2013; R. Bersten, personal communication, August 2, 2013). Because of this, the resources, organisational authority and capacity for co-ordination of these positions appears to have been greater than ever before. This produced higher levels of the application of new media, as well as a greater capacity of interactive elements to be worked into campaign tactics ‘at the ground floor’.

The impact of this professionalisation is also demonstrated in the more pragmatic selection of campaign methods and techniques (S. Laris, personal communication, July 23, 2013). This was evident in the way established online campaigning methods, such as the extensive use of online video-sharing website YouTube, were employed and proven to be effective, in previous election cycles (Chen, 2008) alongside imported methods that were selected on the basis of evidence, over novelty (such as ‘big data’ data mining methods for the customised targeting of emails for fund-raising). Audience response, measured in social media metrics (e.g. Facebook ‘likes’, sharing of content) and financial donations, dominated the thinking of party management about how to measure success in the new media space. ‘Trendy’ concepts that did not meet a strict cost-benefit analysis were excluded from the major campaign’s array of communications tools. Thus, even though smartphone adoption and use has exploded in Australia in recent years (57 percent penetration according to Sadauskas, 2013; Roy Morgan Research, 2013, 13), the only national political party to field a smartphone app in the 2013 campaign was the minor party Rise Up Australia. 5 This reflects the major parties’ desire for, and capacity to purchase, evidence prior to expenditure on new campaigning channels and techniques.

Fundraising online

The outcome of this more strategic adoption of new media for the major parties, is reflected in their capacity to raise funds from a wider supporter base (R. Bersten, personal communication, August 2, 2013). Looking at the use of highly customised, targeted direct email, Snow (2013) reports that the ALP was able to raise $800,000 in small-unit donations during the campaign using these methods. This not only shows how attentive the parties have been to innovations in the United States, but also a willingness to draw from commercial marketing methods. The success of the ALP’s targeted fundraising in the 2013 campaign was achieved through the use of its existing supporter data, as well as through engagement methods that focus on moving recipients’ through a ‘commitment curve’ to build participation in the campaign (R. Bersten, personal communication, August 2, 2013).

This approach focuses on moving recipients up an increasingly steep participation curve which builds their level of commitment to the issue, candidate or organisation over time through disaggregating participation into a set of small steps and tasks (micro-activism) that have low initial participation costs (liking a post or signing a petition). Over time, this pattern of participations builds with increasing ‘asks’ (initial donation, larger or regular donations, more active participation, extensive volunteering, etc.; Heimans, 2013). The strength of this model is that it facilitates political action, without necessarily asking for commitment until after the respondent has a fair amount of emotional ‘sunk costs’ in the issue or organisation (Shearman & Yoo, 2007). This employs respondents’ psychological desire to maintain consistency as a motivator to remain engaged in campaign activities. In addition, strong use of reinforcement messages and the visibility of a community of like-minded participants (‘social proof’) in follow-up communication serves to promote ongoing participation and increased levels of giving.

This type of reinforcement occurred on three levels. First, it way employed by tying donations to specific campaign behaviours, (such as specific advertising purchases). These ads were pushed back to donors to show the direct and immediate impact of their donation. A typical example is illustrative. In the lead up to the electronic media blackout, the Liberal National Party of Queensland asked donors for specific funds to fund an advertising truck (Bruce McIver, ‘Let’s keep our rig on the road!’, bulk email correspondence, 3/9/13) which was then followed by a thanks for support with a photograph of the truck on the streets (5/9/13). The short time lag between ask and reinforcement is important here. Second, request messages could include positive, negative, and factual messaging to reinforce the salience of the initial request and, therefore its respective request (S. Laris, personal communication, July 23, 2013). A good example of this was seen at the outset of the campaign. The ALP made a donation request that focused on a tobacco industry donation to the Liberal Party and asked for a small donation of ‘about the price of a packet of cigarettes’ to counter this influence (Tanya Plibersek, ‘Let’s clear the air ‘, bulk email correspondence, August 1, 2013). This has the advantage of tying the request to a popular hate figure (big tobacco), linking the Liberal party to this malign group, and highlighting the ALP’s internationally groundbreaking tobacco packaging reforms. Similarly, the Liberal Party used reporting of an extremely large union negative campaign to request donations (Brian Loughnane, ‘The Union Bosses’ $12 Million Negative Campaign’, bulk email correspondence, August 16, 2013).Finally, small-unit donations became part of the ‘campaign story’ of the ALP. Labor promoted donations through direct calls from leadership figures to donors, followed by write-ups that explain the motivation behind donation. A good example was ‘Kevin calls Michelle to say thanks for her $5 Donation’ (bulk email correspondence, August 8, 2013) which talks about ‘Michelle from Bundaberg’s journey from swinging voter to donor out of concern about the implications of an Abbott-lead government.’

This type of ‘storytelling’ model of mobilisation reflects lesson drawing from the practices of Online Social Movement Organisations, such as GetUp!, and demonstrates a move to associate support and membership of parties with personal attributes and concerns (Vromen & Coleman, 2013). The shift from behavioural (voting) to attitudinal (concerns) characterisation saw, for example, the ALP providing a set of Facebook profile icons they could use to highlight their support for issues like animal rights, the National Broadband Network and DisabilityCare. This approach picks up on contemporary political practice on social networking sites, demonstrating increased new media cultural literacy from the parties. This shift in strategy also demonstrates the role of lesson transfer from staff moving from activist organisations to parties. For the 2013 campaign, for example, Labor recruited Skye Laris, the former Communications and Campaigns Director of GetUp! to head up their new media strategies.

While the full impact of these strategies on targeted voters is unclear in terms of encouraging attitudinal change, micro-fundraising significantly leveled the playing field in terms of the capacity of the ALP to match Coalition advertising expenditure. The return of Kevin Rudd to the leadership helped to improve pre-election fundraising, but the ability to raise over 10 percent of their total advertising budget using this method, is likely to be of interest to all parties. Overall, the two major political parties spent very similar amounts of money on advertising in the 2013 campaign, as illustrated in Table 1. This needs to be read, however, in conjunction with non-party electoral advertising expenditure that tended to support particular parties (such as the $3.9m spent by the Australian Council of Trade Unions which tended to support the ALP (which would make this fundraising around nine percent of the effective advertising expenditure), and GetUp’s half-million dollars of expenditure that supported the Greens 6).

Table 1: Australian Party Advertising Expenditure, June 2-August 31, 2013 (Source: Nielsen Australia) 7

| PARTY | EXPENDITURE |

|---|---|

|

Australian Labor Party |

$6,526,000 |

|

Liberal Party of Australia |

$6,610,000 |

|

The Nationals |

$339,000 |

|

Australian Greens |

$2,375,000 |

|

Palmer United Party |

$2,375,000 |

Online advertising and negative messaging

While new media has advantages in its highly targeted deployment (e.g. through selecting specialised online publications, through Google AdWords targeted advertising, geo-location, or via SNS profile matching), immediate performance measurement capacity (unique viewers, click-through, repost/re-tweet and ‘like’ rates) and interactivity, the value of online advertising is also determined by structural electoral factors. These include access to the electoral role by parties and candidates (increasingly useful as data matching across multiple databases becomes simpler and more effective) and campaign laws. The electronic media (broadcast) blackout increases the importance of online advertising in the last days of the campaign, with the Liberal party purchasing expensive large ‘floating ads’ to push into the consciousness of viewers lost to them on TV and radio.

These types of highly intrusive advertisements demonstrate the contemporary phenomena of ‘attention scarcity’ in a heavily mediatised society. This is the inverse problem of information scarcity pre-digital media, where the cost of communication capacity was high due to a scarcity of capacity (Hartley, et al., 2013). This heightens known problems in reaching disengaged voters (Mills, 1986). While the focus on social media by political parties and candidates is often attributed to an erroneous assumption that these are good spaces to access younger voters with lower partisan commitment (see Chen, 2013 for an extended discussion of this fallacy), the move into advertising in SNSs tends to be driven by the tendency for these audiences to be ‘active’ – ‘produsers’ engaged in content creation and curation (Bruns, 2008). As these audiences are attentive to the content they are handling, they have a higher likelihood of cognitive engagement with, and elaboration of, messages communicated to them (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). This makes advertising and interaction with voters in SNSs more ‘sticky’ and lowers the need (and cost) to constantly re-engage voters with messages to sustain commitment to voting day (a problem of low-attention, ‘peripheral route’ media consumption). While not seen in the 2013 campaign, parties are likely to combine this type of primary route communication method with pre-poll voting (a more general trend, still largely promoted via direct mail in 2013; AEC, 2013) to ‘lock in’ and enumerate voter conversions in future years.

Negative campaigning by the two major parties online was seen in the use of the well-established method of using negative websites that were cross-promoted from parties’ other properties. The Liberals provided stark comparison between the two potential future outcomes with its ‘Election Choice 2013. Choose Wisely’ Facebook video that let you see the future under a Coalition or Labor administration (with the Labor future presented as economically break and unstable). In addition, they used an online ‘Cost of Labor’ calculator tool via Facebook to highlight their arguments for lower cost of living under a proposed Coalition government (Jericho, 2013). This is an enhancement of activities undertaken in previous elections (such as the National’s ‘Tax cut calculator’ used in the 2005 New Zealand election; Hager, 2006), but one that focused on the perceived poor economic management of the Labor government. The Coalition was also cleverly able to turn Labor’s incumbency advantages against them. Picking up on hostile reactions to Government-funded advertising promoting Rudd’s change of policy on asylum seekers (somewhat weakly defended by the ALP as aimed at informing people smugglers to the change in policy; Ireland, 2013a), the Liberal party used an online petition to highlight Rudd’s personal hypocrisy, while further building its electoral database.

Speech regulation and new arenas of conflict

In addition to knowledge transfer, the international character of the election was also apparent in the way elections are increasingly multi-level games. The Liberal Party employed YouTube’s Terms of Service (user shrink-wrap licence) to have an ALP video taken down by the US-based content host (Ireland, 2013b). In this case, the established practice of re-using video content to parody an opponent’s advertisement was challenged under strict intellectual property rules, demonstrating the seriousness with which online video is seen among the parties following its high level of use in the previous two federal electoral cycles (Chen, 2008). A similar intervention was aimed at the Liberals. Tony Abbott’s Twitter account was subject to an artificial inflation of followers and accusations that the Party had purchased fake followers to increase his perceived popularity (Chan, 2013), leading to the service culling fake accounts during the campaign (Ralston, 2013).

Social media in the campaign

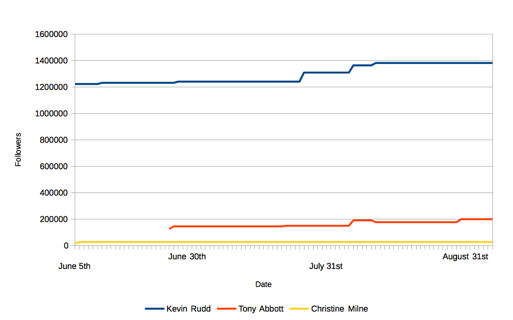

The role of social media in the 2013 election demonstrated the new maturity of this channel in electioneering in Australia in the way online video became established in the 2007 campaign (Chen, 208). Kevin Rudd, a long established user of Twitter, took his significant number of followers into the 2013 campaign. He has previously been seen to be an effective user of this channel to sustain his personal ‘brand’. Tony Abbott, on the other hand, is a comparative latecomer to the medium, and tended to employ it more sparingly in the lead up to the campaign. The outcome variance is reflected in the very different way the two major parties envisaged social media: With Labor focusing on more casual and personal messaging and images of the leader (typified by Rudd’s use of ‘selfies’ with supporters and informal photos like his shaving cuts), 8 the Liberal Party focused more on the provision of specific campaign information and key messages (Loughnane quoted in Taylor, 2013). This reflects the desire by the ALP to highlight the leader, and not the party, and the opposite intention of the Liberal party. The impact these choices are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Leaders’ Twitter followers, June-September 2013 (source: compiled from Twitaholic)

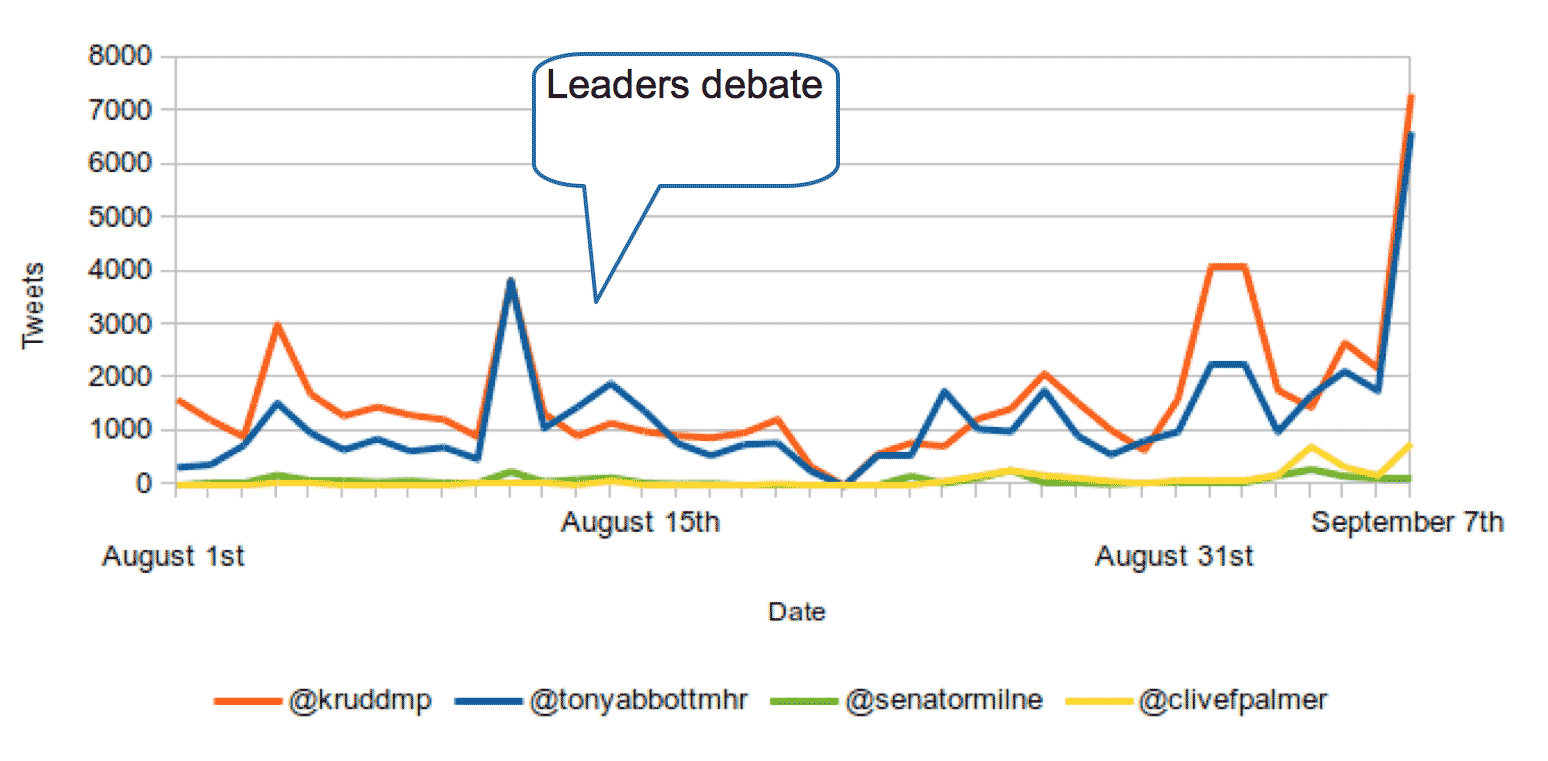

While follower numbers are one measure of the effectiveness of a leader’s campaign, the capacity to generate third-party discussion can also be employed as a good indicator of a campaign’s capacity to break through into the public debate. If we look at Figure 2 below, we can see that the two major leaders attracted similar levels of tweets directed at their accounts throughout the campaign. This demonstrates that, while follower numbers can be worked on over time, situational factors – such as the virtual inevitability of Abbott’s victory – can quickly increase your visibility in the discursive environment of Twitter. This figure also shows the impact of media events on campaign discussion: with a spike during the first leaders’ debate (broadcast free-to-air) and a smaller spike during the final debate (broadcast on pay-TV with a smaller audience). 9

Figure 2: @[leader] Tweets during the 2013 election campaign (Source: compiled from Topsy)

For party leaders like Christine Milne (Australian Greens) and Clive Palmer (Palmer United Party), their comparatively low level of discussion on Twitter reflects the power of the two-party system to focus attention away from smaller – if potentially very significant – parties. However, what is interesting in this figure, is how Palmer’s level of discussion grew throughout the campaign, reaching a higher daily average by the end of the first week of the campaign. This reflects the manner in which Palmer’s personality and novelty was able to break through into the public consciousness, albeit in a comparatively low level relative to the major parties. If we look at Table 2, we can see that this general tendency was also matched in blog references to the leaders and their parties.

Table 2: Daily average blog mentions, August-September 2013 (Source: Icerocket)

| Leader/party name | Daily average blog mentions (per post) |

|---|---|

| Kevin Rudd | 72.00 |

| Tony Abbott | 103.00 |

| Christine Milne | 2.90 |

| Clive Palmer | 9.00 |

| Labor Party | 221.13 |

| Liberal Party | 176.28 |

| Australian Greens (The Greens) 10 |

21.82 (646.73) |

| Palmer United (Palmer Party) |

17.98 (27.83) |

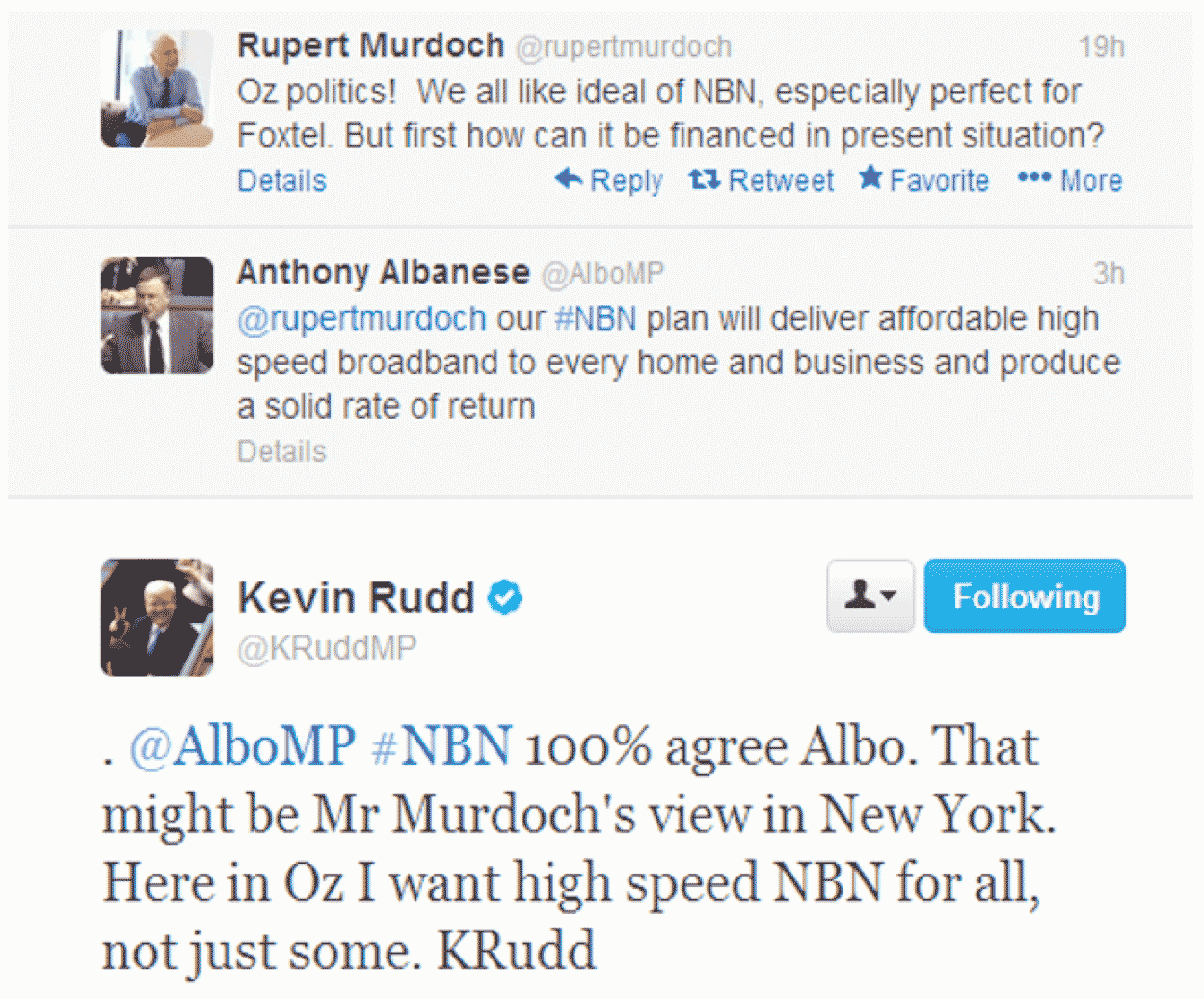

One of the interesting features of the election campaign was the role of News Limited’s Rupert Murdoch. Murdoch and his media holdings were clearly in favour of a change of government, but Murdoch’s personal tweets endorsing Tony Abbott as a ‘conviction politician’ and comments on policy allowed the ALP space to use the channel to engage with the media baron over his commercial interest in the outcome of the campaign (see Illustration 1). In doing this the ALP were further able to link the new media channel with their bolder telecommunications agenda for complete fibre-to-the-premises (Illustration 1), a policy with strong support among this constituency of heavy internet users (Battersby, 2013).

Illustration 1: Elite cross-talk on Twitter, National Broadband Debate, 5-6 August 2013

While not every major party had a foil like Murdoch against whom to tilt, this type of message extension strategy was employed by both parties through social media. Generally, this focused on messaging aimed at journalists and key opinion leaders to enhance daily campaign themes and refute opponents’ claims (S. Laris, July 23, 2013 personal communication). Particular events, like the leadership debates, also saw the use of inoculation tools distributed via social media. ‘Inoculation’ is a type of message framing aimed to promote resistance to influence (Pfau, 1997). Inoculation strategies employed included Labor distributed a weblink to their ‘Reality check: top four Abbott deceptions to watch out for in the debate’ which provided pre-determined rebuttals to claims likely to be made by the Opposition leader. On a similar level, the Liberal party provided an online ‘Ruddy-made Excuses’ generator that allowed you to play audio clips of Kevin Rudd making excuses for his government’s performance.

Assessing performance: Cost and benefit

Overall, while the Liberal Party’s new media campaign has been negatively assessed by marketing experts because of its comparatively staid character (Sprokkreeff, 2013)11 and lack of personal engagement between the Opposition leader and supporters during the campaign (McGregor in Taylor, 2013), the Liberals were able to outperform Labor in driving traffic to their website through both search engines and via social media channels. This is illustrated in Table 3 and demonstrates that, in addition to significantly higher destination traffic to their main party website during the campaign (30 percent higher), the Liberals were able to do this at lower cost in search engine advertising, and more than three times the rate of referrals via social media sources than the ALP. The Liberals used online video more effectively and were far more visible on Facebook. While Kevin Rudd was able to dominate visibility on Twitter, the comparatively smaller size of this medium (with 2.5 million Australian users compared with Facebook’s 11.5 million; Frank Media, 2013) reveals its weakness, even if it has greater inter-media agenda setting potential. What is notable, however, is how constituency factors can be significant in shaping new media performance. As has been identified by others in previous campaigns (Grant, et al., 2010) the Australian Greens maintain a remarkably high online visibility, even as general media coverage of their campaign was extremely low.

Table 3: Comparative party website performance, August 2013 (compiled from SimilarWeb)

| alp.org.au | liberal.org.au | nationals.org.au | greens.org.au | palmerunited.com | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian site rank (popularity) | 2,323rd | 1,844th | 29,543rd | 2,726th | 6,172nd |

| August visitors | 170,000 | 220,000 | n/a | 120,000 | 50,000 |

| % referral from search engine | 48.2% | 39.81% | ‘ | 35.9% | 52.26% |

| % of search result paid | 23.70% | 13.95% | ‘ | 0.52% | 0% |

| % referral from social media | 4.83% | 16.21% | ‘ | 13.10% | 12.67% |

| Source: Facebook | 72.76% | 49.69% | ‘ | 88.66% | 98.23% |

| 20.66% | 6.58% | ‘ | 6.09% | 1.77% | |

| 6.16% | 0.10% | ‘ | 4.67% | 0% | |

| ‘ YouTube | 0.43% | 43.80% | ‘ | 0.26% | 0% |

The candidates: Social media and silence

While the party-centric nature of Australia’s electoral culture highlights leaders and encourages centralised message control, individual candidates are not completely invisible in the electoral process. In the 2013 election, a number of electorate races detached from national campaign themes and were driven by local issues or personalities. One of the most prominent of these was the race in Indi (regional Victoria) where the same campaigning platforms employed by the national campaign teams (such as the campaign management tool Nation Builder) were used for a sophisticated online and grassroots campaign with strong levels of online fund-raising ($113,000; Whinnett, 2013). In this case, the use of new media, as a strategic resource for other campaigning, provided the edge that allowed a strong independent candidate to overturn a front-bench member and touted cabinet minister. This conforms to the historical evidence that points to individual candidates’ use of new media as a marginal benefit that can, in close contests only, be a decisive tool for ‘outsider’ candidates (Gibson & McAllister, 2011: 238-40).

New media use

Based on content analysis undertaken during the campaign period, Tables 4 (the so-called ‘web 1.0’ technologies) and 5 (‘web 2.0’ services), illustrate the deployment of new media channels by candidates in the 2013 election campaign. The breakdown by party and other candidate attributes shows a considerable divergence between parties that are likely to form government and those that are not, with only minor gender variation. In contrast to the national campaign, there is a considerably higher level of channel use, and intensity of use by the ALP over their rivals in the coalition. This makes the 2013 election quite different to previous campaigns.

Table 4: Web 1.0 Campaigning tools, use and features

| All | Labor | Coalition | Greens | Minor (ex-Greens) |

Incumbents | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n |

160 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 99 | 19 | 51 |

| Email address % | 80.0 | 90.0 | 76.2 | 70.0 | 70.7 | 94.7 | 94.1 |

| Website % | 26.9 | 75.0 | 38.1 | 15.0 | 12.1 | 89.5 | 19.6 |

| Candidate blog | 8.8 | 25.0 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 26.3 | 5.9 |

| Donation/merch | 7.5 | 15.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 5.3 | 5.9 |

| Embed. Video | 7.5 | 20.0 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 4.0 | 31.6 | 3.9 |

| Contact form | 21.9 | 65.0 | 38.1 | 10.0 | 8.1 | 68.4 | 15.7 |

| Podcast | 1.9 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 10.5 | 0.0 |

| Push-to-talk | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| RSS feed | 2.5 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 |

| Survey / poll | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 15.8 | 0.0 |

| Search | 8.1 | 40.0 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 42.1 | 2.0 |

| Sitemap | 1.3 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 |

| Social media link | 18.8 | 50.0 | 23.8 | 10.0 | 12.1 | 52.6 | 13.7 |

| Subscription | 10.0 | 40.0 | 14.3 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 42.1 | 3.9 |

| Volunteering | 7.5 | 10.0 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 5.3 | 3.9 |

| Mini-site % 12 | 69.4 | 100.0 | 76.2 | 60.0 | 51.5 | 94.7 | 74.5 |

| Candidate blog | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 |

| Embed. videos | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 3.9 |

| Contact form | 5.0 | 10.0 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 15.8 | 9.8 |

| Podcast | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Push-to-talk | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Subscription | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 |

| Social media link | 61.9 | 95.0 | 71.4 | 60.0 | 41.4 | 89.5 | 68.6 |

These two tables are notable in their linkages. While fundraising has been very significant at the level of parties, there remains a very low uptake in fund-raising gateways on candidates’ websites (the majority of those that include these options direct towards party payment systems, rather than local-level ones). Overall, these sites remain remarkably feature-poor given the availability of no-/low-cost, highly sophisticated content management systems. Where campaign websites have developed over the last three years is in the inclusion of social media tools: the ability to simply post content from candidates’ sites onto social media platforms, as well as the ability to ‘like’ candidates through embedded buttons. Many sites also provided social feeds from Facebook and Twitter into the site. Thus, while the use of websites by candidates has been increasingly (on average) slowly over the past decade, the adoption of SNSs and social media channels by candidates has been extremely rapid. While this is associated with the low cost of adoption of these services, 13 their perceived value to candidates has also been driven by the disproportionate attention given to some channels over others (Twitter, for example).

Table 5: Social media campaigning tools, use and ‘followers’ (* inflated due to a single large outlier)

| All | Labor | Coalition | Greens | Minor (ex-Greens) |

Incumbents | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facebook profile % | 66.9 | 95.0 | 61.9 | 70.0 | 51.5 | 84.2 | 86.3 |

| Friends mean | 524.7 | 14,65.5 | 752.2 | 469.6 | 134.1 | 17,11.5 | 433.9 |

| ‘ median | 182.0 | 12,13.0 | 121.0 | 245.0 | 92.0 | 13,52.0 | 183.0 |

| ‘ St dev | 888.1 | 15,56.1 | 17,94.0 | 495.4 | 167.3 | 16,01.6 | 675.4 |

| YouTube channel % | 20.0 | 45.0 | 14.3 | 35.0 | 12.1 | 63.2 | 19.6 |

| Subscribers mean | 43.8 | 9.6 | 15.3 | 15.1 | 98.0 | 8.5 | 14.1 |

| ‘ median | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 3.0 |

| ‘ St dev | 164.4 | 11.9 | 17.0 | 26.5 | 265.1 | 10.4 | 23.5 |

| Linkedin profile % | 25.6 | 15.0 | 19.0 | 20.0 | 21.2 | 21.1 | 25.5 |

| Connections mean | 190.7 | 89.0 | 51.0 | 259.5 | 147.3 | 296.3 | 153.5 |

| ‘ median | 109.0 | 50.0 | 47.0 | 267.0 | 52.0 | 335.5 | 109.0 |

| ‘ St dev | 199.9 | 100.4 | 45.2 | 278.0 | 188.8 | 239.0 | 166.9 |

| Twitter profile % | 33.8 | 70.0 | 28.6 | 50.0 | 21.2 | 57.9 | 41.2 |

| Followers mean | 3,770.9 | 4,545.6 | 1502.8 | 939.0 | 5,296.9* | 5,920.5 | 2,490.2 |

| ‘ median | 191.0 | 2272.0 | 136.5 | 103.5 | 32.0 | 29,36.0 | 111.0 |

| ‘ St dev | 15,175.7 | 9,701.0 | 22,12.8 | 1,551.2 | 22,832.3 | 106,44.9 | 8,175.2 |

Central control and candidate invisibility

One of the long-standing interests of new media researchers has been the impact of these technologies on the distribution of power. In the 2013 election, greater visibility online is strongly correlated with electoral performance (as measured in terms of the number of first-preference votes received): 0.62. To interpret this as seeing new media as a path to electoral success, reverses causality, however. As in previous election cycles, a higher level of online visibility is positively correlated with both incumbency (0.39) and representing an established party of government (0.60). This reflects both the cultural dominance of the two-party system, as well as a recognised tendency towards the ‘normalisation’ of new media use by established political actors in Australia (Gibson % Ward, 1998): the higher level of utilisation of entrenched political organisations of new media given their structural and economic advantages due to visibility and cartel action (Pedersen, 2004:88). In the ‘real’ competition between the two major parties, the average visibility of Labor candidates was higher than that of Coalition candidates: both in terms of the number of online channels they employed during the election, as well as the popularity of these channels. These candidates are likely, therefore, to have received modest benefits from their investment in new media, but this remains considerably secondary to their party campaigns.

The under-performance of Liberal candidates was a strategic decision made by their party. On the question of candidates’ availability for the public during the election, there has been considerable discussion of the tendency of the Liberal party to resist access to the media by their low-profile candidates during the 2013 campaign (Milman, 2013). While there is has been speculation that this was due to particularly poor performance of the candidate for Greenway at the opening of the campaign (whose inability to recall the core policy elements of the Liberal’s boarder regulation policies became subject to considerable media attention in the first week of the campaign; McKenny, 2013) 14 , restrictions on the use of social media were in place before the campaign. In late 2012 preselected candidates were strongly discouraged from using Twitter by the party’s central office (Wright, 2012), a suggestion that was largely followed by candidates. As Table 6 shows, Coalition candidates were the only group to consistently use fewer new media channels in the 2013 than in previous years.

Table 6: Changes in use of new media channels, 2004-13

| Party | Year | Email % | Campaign Website % | Mini-site % | SNS % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALP | 2004 | 97 | 30 | n/a | n/a |

| 2007 | 100 | 48 | ‘ | ‘ | |

| 2010 | 96 | 48 | 96 | 62 | |

| 2013 | 90 | 75 | 100 | 95 | |

| Coalition | 2004 | 98 | 44 | n/a | n/a |

| 2007 | 97 | 55 | ‘ | ‘ | |

| 2010 | 94 | 50 | 92 | 76 | |

| 2013 | 76 | 38 | 76 | 62 | |

| Australian Greens | 2004 | 100 | 8.1 | n/a | n/a |

| 2007 | 94 | 9 | ‘ | ‘ | |

| 2010 | 93 | 4 | 100 | 92 | |

| 2013 | 70 | 15 | 60 | 70 |

Conclusion and implications

In examining the use of new media by candidates and parties in the 2013 Australian federal election, this article has painted a picture of the way a variety of online communications channels have been employed, and the relationship between channel adoption, organisational capacity and media logics. In answer to Gibson and Cantijoch’s (2011 question), it appears evident that new media has finally ‘arrived’ in Australia. The two major political parties have demonstrated a more sophisticated application of new media than in previous campaigns, with clear alignment to strategic objectives (capacity building) and tactical considerations (mobilisation and messaging). The particular success of the ALP in online fundraising will be the most visible lesson of the campaign, but the Liberal Party’s effective integration of websites with social networking advertising is a important development that has far-reaching implications because it speaks to the capacity of the major parties to integrate data-driven and targeted campaigns with their financial resource advantages to effectively begin to drive traffic towards their ‘static’ online properties.

At a wider level this would appear to reinforce the long-standing view of political normalisation of new media established by Gibson in the early noughties: powerful social actors are able to leverage their resources to co-opt and dominate new communications channels. Certainly, the considerable constraint on Liberal candidates’ use of new media does not appear to have limited the party’s overall campaign effectiveness. This points to even further centralisation and top-down control of electoral campaigns in the future, with implications for the treatment of local issues and regional variations within Australia. While this might be seen as evidence of ‘presidentialism’, the tendency of the Liberal Party to focus attention on their ‘party brand’ over the leadership figure demonstrates that centralisation does not automatically lead to personalisation. Variations from this general tendency can be seen in races like Indi where local organising can work through leveraging prêt-à-porter toolsets for effective fundraising, the comparative autonomy of senior party figures to have more extensive online visibility, and greater online visibility of parties like the Greens with their ‘natural’s online constituency. These tendencies, however, represent only minor variations in the wider political cultural norm in Australia that narrows the focus towards the two major party groupings.

Notes

1 With thanks to Associate Professor Ariadne Vromen who provided initial comments on this article and the two referees for this article who provided some very helpful feedback on the initial submission.

2 Where the visibility of minor parties serves as a proxy for an increased democratic electoral process.

3 For a discussion of the broader media context of elections in Australia, see Young (2011). For a discussion of the construction of new types of social media public sphere’s in the Australian political context, see the Mapping Online Publics project at http://mappingonlinepublics.net/

4 A sub-media, in this context, is a communications technology defined by a specific technical standard. Thus, within the arena of internet communication electronic mail and world wide web content are sub-media, whereas blogs, webpages, and social networking services are not. These latter examines represent different genre conventions, channels, and/or online communities. However, it is recognised that this classification is increasingly ambiguous as different sub-media become integrated into the web environment and the distinctions between types of online interaction are more usefully defined in terms of their social meaning. The article, therefore, uses ‘channel ‘ as a meta-descriptor.

5 The Western Australian ALP and Victorian Liberal Party also maintain their own smartphone apps. The Victorian Party pushed out an update with federal polling information for the 2013 national campaign.

6 Other third-party campaigns, such as the Salary Packing Industry Association’s $10 million ‘Who’s Next?’ campaign attacking changes to the tax treatment of fringe benefits by the ALP are likely to have supported Coalition vote decisions (Chung, 2013). The level of expenditure on all of these significant campaigns (including outdoor, online, print and television elements) is not known at the time of writing.

7 These totals, unfortunately exclude online advertising, but include regional and metropolitan television, regional and metropolitan press, magazines, metropolitan radio, outdoor advertising, and direct mail.

8 Kevin Rudd has also pioneered the use of specific social media channels aimed at ethnic and linguistic groups, having over 500,000 followers on the popular Chinese-language version of Twitter, Weibo.

9 Unfortunately, as noted in this figure, there is a missing data problem at the 21st August. This is the date of the second leaders’ debate.

10 Given the tendency to refer to the party as ‘the Greens ‘, a search term with captures a far wider set of references (bracketed), both figures in this table are unlikely to be representative. A similar problem exists for the Nationals (254.03 references per day).

11 This compares to some pre-campaign material, such as the Liberal’s ‘Headless Chooks ‘ online video that was quite humorous and appeared to signal a return to the use of light-hearted animations by the party, such as the ‘Kevin-o-lemon ‘ series of advertisements.

12 Small websites hosted within the party domain that are provided by the party (normally through a standard template).

13 That this is not the sole determinant of adoption is evidenced by the differential rates of take up, but also the comparatively low levels of other free service adoption in previous elections, such as third-party blog hosts.

14 The party also lost a candidate early in the campaign, following media reports of off-colour and offensive jokes on a non-campaign website run by the candidate for Charlton, Kevin Baker (Davidson and Chan, 2013).

References

AEC (2013, September 5). Early voting tracking to record levels as polling day preparations ramp up. Media Release. Canberra: Australian Electoral Commission.

Barker, C. (2003). Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice, Second Edition. London: Sage.

Battersby, L. (2013, September 13). Malcolm Turnbull gives thumbs down to fibre NBN petition. The Age. Retrieved from: http:.//www.theage.com.au/it-pro/government-it/malcolm-turnbull-gives-thumbs-down-to-fibre-nbn-petition-20130913-hv1po.html

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Chan, G. (2013, August 11). Tony Abbott’s office denies purchasing Twitter followers after numbers spike. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/aug/11/tony-abbott-twitter-followers-spike

Chen, P.J. (2013). Australian Politics in a Digital Age. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Chen, P.J. (2012). The new media and the campaign. In M. Simms, & Warhurst, J. (Eds.) Julia 2010: The Caretaker Election (pp. 65-84). Canberra, Australia: ANU E Press.

Chen, P.J. (2010). Adoption and use of digital media in election campaigns: Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Public Communication Review, 1, 3-26.

Chen, P.J. (2008). Australian political parties’ use of Youtube 2007. Southern Review: Communication, Politics and Culture, 41(1), 114-41.

Chen, P.J. (2005). The new media: E-lection 2004?. In M. Simms, & Warhurst, J. (Eds.) Mortgage Nation: the 2004 Australian Election (pp. 117-130). Perth, Western Australia: API Network.

Chen, P.J. & Walsh, L. (2010). E-lection 2007? Political competition online. Australian Cultural History, 28(1), 47-54.

Chung, F. (2013, August, 13). $10 million FBT blitz kicks off. AdNews. Retrieved from http://www.adnews.com.au/adnews/10-million-fbt-blitz-kicks-off

Costar, B. (2012) Seventeen days to power: Making a minority government. In Simms, M & Warhurst, Julia 2010: The Caretaker Election (pp. 357-370). Canberra: ANU E Press.

Davidson, H. & Chan, G. (2013, August 20). Liberal Kevin Baker resigns over website with offensive material. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/aug/20/liberal-candidate-offensive-jokes-website

Frank Media. (2013). Social Media Statistics Australia – April 2013. Retrieved from http://frankmedia.com.au/2013/05/01/social-media-statistics-australia-april-2013/

Gibson, R.K. (2003). Letting the daylight in? Australian state parties and the WWW. In Gibson, R.K. Nixon, P., & Ward, S.J. Net Gain? Political Parties and the Internet (pp. 139-161). London: Routledge.

Gibson, R.K. (2002). Virtual campaigning: Australian parties and the impact of the internet. Australian Journal of Political Science, 37(1) 99-130.

Gibson, R.K. Ward, S.J., Chen, P.J., & Lusoli, W. (2007) Australian government and online communication. In Young, S. (Ed.). Government Communication in Australia (pp. 473-491). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gibson, R. & Cantijoch, M. (2011). Comparing online elections in Australia and the UK: Did 2010 finally produce ‘the’ internet election?. Communication, Politics & Culture, 44(2) 4-17.

Gibson, R. & McAllister, I. (2009) Australia: Potential Unfulfilled? The 2004 election online. In Ward, S., Owen, D., Davis, R., & Taras, D. Making a Difference: A Comparative View of the Role of the Internet in Election Politics (pp. 35-56). Lanham: Lexington Books.

Gibson, R. & McAllister, I. (2011) Do online election campaigns win votes? The 2007 Australian ‘YouTube’ election. Political Communication, 28(2): 227-244.

Gibson, R. & Ward, S. (1998). UK political parties and the Internet – ‘politics as usual’ in the new media?. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 3: 14-38.

Goot, M. 2009). Is the news on the internet different? Leaders, frontbenchers and other candidates in the 2007 Australian election. Australian Journal of Political Science, 43(1): 99-110.

Grant, W., Moon B., & Grant, J. (2010). Digital dialogue? Australian politicians’ use of the social network tool twitter. Australian Journal of Political Science, 45(4): 579-604.

Hager, N. (2006). The Hollow Men: A Study of the Politics of Deception. Nelson: Craig Potton.

Hartley, J., Potts, J, Cunningham, S., Flew, T., Keane, M., & Banks, J. (2013). Key Concepts in Creative Industries. Sage: London.

Heimans, J. (2013) The Commitment Curve: Why Spin Isn’t a Match For Memes. Gsummit: San Fransicso.

Ireland, J. (2013a, August 9). Row erupts over asylum ad campaign. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/federal-election-2013/row-erupts-over-asylum-ad-campaign-20130809-2rmwl.html

Ireland, J. (2013b, August 7). Liberal complaints see Labor parody ad removed from YouTube. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/federal-election-2013/liberal-complaints-see-labor-parody-ad-removed-from-youtube-20130807-2rgih.html

Knott, M. (2013, April 29) Fact off: ABC and Fray’s PolitiFact dig into pollies’ spin. Crikey. Retrieved from http://www.crikey.com.au/2013/04/29/fact-off-abc-and-frays-politifact-dig-into-pollies-spin

Krotz, F. (2008). Media connectivity: concepts, conditions, and consequences. In Hepp, A., Krotz, F. & Moores, S. (Eds.). Network, Connectivity and Flow: Key Concepts for Media and Cultural Studies. New York: Hampton Press.

Macnamara, J.R. & Kenning, G. (2011). E-electioneering 2010: Trends in social media use in Australian political communication. Media International Australia, 139, 7-22.

Maley, J. (2012, October 11). Gillard’s fiery retort: Did the mainstream media get it wrong? The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/gillards-fiery-retort-did-the-mainstream-media-get-it-wrong-20121011-27eqg.html#ixzz2gSbgMYv4

McKenny, L. (2013, August 6). Diaz and confused: Candidate misses the points ‘, Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/federal-election-2013/diaz-and-confused-candidate-misses-the-points-20130806-2rb1v.html

Mills, S. (1986). The New Machine Men: Polls and Persuasion in Australian Politics. Ringwood: Penguin.

Milman, O. (2013, September 11). Liberal Andrew Nguyen says party lacks ‘ethnic brain’. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/11/liberal-andrew-nguyen-western-sydney

O’Donnell, P., McKnight D., & Este, J. (2012) Journalism at the Speed of Bytes: Australian Newspapers in the 21st Century. Sydney: Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance.

Pedersen, K. (2004) From aggregation to cartel? The Danish case. In Lawson, K. & Poguntke, T. (Eds.). How Political Parties Respond: Interest Aggregation Revisited (pp. 86-94 ). Abingdon: Routledge.

Petty, R. & Cacioppo, J. (1986) Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Pfau, M. (1997). Inoculation model of resistance to influence. In Barnett, G & Boster F. (Eds.). Progress in Communication Sciences: Advances in Persuasion 13 (pp. 133-171). New York: Ablex Publishing.

Ralston, N. (2013, August 11). Tony Abbott’s Twitter followers drops after fake buyers culled. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/federal-election-2013/tony-abbotts-twitter-followers-drops-after-fake-buyers-culled-20130811-2rpt2.html

Roy Morgan Research. (2013). State of the Nation Australia: Spotlight on Federal Election 2013, 20 – 21 August. Sydney: Roy Morgan Research.

Sadauskas, A. (2013, May 17). 57% of Australians have smartphones, adoption rates outpace the US and Europe. Smart Company. Retrieved from http://www.smartcompany.com.au/information-technology/049727-57-of-australians-have-smartphones-adoption-rates-outpace-the-us-and-europe.html

Shearman, S. & Yoo, J. (2007). ‘Even a Penny Will Help!’: Legitimization of paltry donation and social proof in soliciting donation to a charitable organization. Communication Research Reports, 24(4): 271-282.

Snow, D. (2013, September 9). How Kevin Rudd’s 2013 election campaign imploded ,The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/federal-election-2013/how-kevin-rudds-2013-election-campaign-imploded-20130908-2teb1.html

Sprokkreeff, P. (2013, August 6). Abbott falls short in the social media election. The Drum. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-08-06/sprokkreeff-social-media-election/4866960

Taylor, L. (2013, September 11). Coalition digital campaign ‘slick’ but Rudd selfies more engaging ‘, The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/11/digital-campaigns-coalition-and-labor

Van Onselen, A. & van Onselen, P. (2008). On message or out of touch? Secure web sites and political campaigning in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science, 43(1): 43-58.

Vromen, A. & Coleman, W. (2013). Online campaigning organizations and storytelling strategies: GetUp! in Australia. Policy & Internet, 5: 76-100.

Whinnett, E. (2013, September 22). Hipsters help Cathy McGowan beat Sophie Mirabella in rural seat of Indi. Herald Sun. Retrieved from http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/hipsters-help-cathy-mcgowan-beat-sophie-mirabella-in-rural-seat-of-indi/story-fni0fit3-1226724477760

Wright, J. (2012, December 9). Liberal gag twits. The Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/technology/technology-news/liberals-gag-twits-20121208-2b284.html

Young, S. (2011). How Australia Decides: Election reporting and the media. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Young, S. (2003). A century of political communication in Australia, 1901-2001. Journal of Australian Studies, 78: 97-110.

About the author

Dr Peter John Chen is a lecturer in politics and media at the University of Sydney. He is the author of Australian Politics in a Digital Age (ANU E Press, 2013). His research interests focus on Australian politics, new media and political practice, and animal welfare politics.

Contact: peter.chen@sydney.edu.au; Department of Government and International Relations; University of Sydney; Sydney 2006; 0432845766

Profile: http://sydney.edu.au/arts/government_international_relations/staff/profiles/peter.chen.php