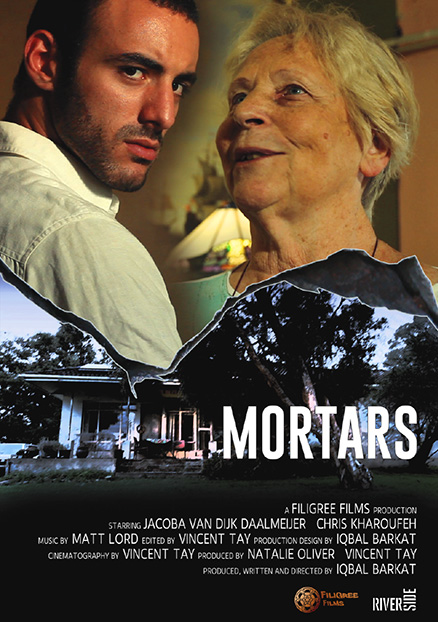

Of war, bricks and ‘Mortars’ (2013): Written and directed by Iqbal Barkat (73 mins)

Asha Chand

University of Western Sydney, Australia

We mortals perish and wither

But the stars on high do not

The monuments and hills remain when we are gone …

Arabian poet Labid (Abu Aqil Labid ibn Rabiah) c.560 –c.661.

Mortars is a 73 minutes-long feature film, narrated using silence resonating with poetic verses in an Arabic voice, all intertwined with the art of living in spaces man owns and invades. While it pushes the viewer beyond the fixtures of place and space into the realm of the unknown with numerous twists and turns that take place in one Sydney location, it brings out the realities of the human condition across the globe, crossing all physical and psychological boundaries, wrenching the heart and leaving the viewer to search the soul for the meaning and purpose of life.

The powerful narrative of Mortars is built around the physical structures of a home falling apart as a result of years of detonations in the adjacent bushland; a home on which cracks appeared as soon as the foundation was laid, one which is shaken in its frame with the bomb-like sounds of aircraft flying overhead.

The film is based on the poetry of Labid, who wrote at a time when Islam was spreading through Arabia. The relevance of his writings have echoed through time and space to present a challenging reality in a new world order for human beings as they grapple with the ‘fear’ of Islam, terrorism, asylum seekers, new migrants and the unknown, unfamiliar faces that turn up as refugees in modern day western societies.

Political in its undertones, the film by Sydney-based academic and filmmaker Iqbal Barkat packages the politics of time and space, as well as the social order, which pinch human consciousness like the pricks from a barbed-wire fence as one manoeuvres to cut through the trapped space. This space, while suffocating, is a psychological reality for each human soul at some stage of their journey through life.

Anticipation builds in the first scene of this budget film with news from the world echoing through shots of barbed-wire fences, a man running as maps of the world come and go in a flash. Then there is serenity, a kind of peace and beauty as the camera tracks into the front of a house, capturing it from a vantage point where the sun casts its radiance and brings out a beautiful picturesque home.

The next scene captures the homeowner in her space, attending to the usual errands of making a ‘cuppa’, the spinning spider’s web in the backyard projects the web of life in which man is trapped. The movie captures the various stages of this spinning web by presenting the two characters whose lives collide in a chance meeting.

The main character, Jackie, comes alive as a dear old soul who would give a hungry man bread, hot soup and a place to sleep. She is, however, fierce in her own right, a lone woman fighting a long, unresolved battle with the armed forces over the cracks in her home which had been appearing in the walls since 1956 when she first took up residence.

Set in 2014 in Orchard Hills in Sydney’s western suburbs, the film takes the viewer into Jackie’s space and home, decked in lush greenery and hiding some old and derelict equipment, some perhaps relics of buildings long demolished. Jackie’s heart bleeds over a long inflicted wound, the scar of which speaks through the walls of her home.

A car drives up the dusty road … it is Jackie. Soon after a police car arrives, the policeman is on a search mission. In the foreground a young man’s hands creep through the grass, finding a grip. A barren tree with on which is perched a lone bird, tells another yarn of the human condition. Not far away, kangaroos stand tall and alert.

There is lull before the storm.

The young man has black plastic from a garbage bag and cardboard for shelter in the shrub, a stone’s throwaway from Jackie’s haven.

Jackie is painting: creating her own beauty on canvass when her solitude is disturbed.

‘What do you want?’

‘I need to stay.’

‘Oh.’

The close up of the man speaks volumes as the bird flutters away with the Arabic voice resonating:

‘I am not sad as it is fate that parted us

And it is fate that every young man will one day fall.’

The expanded pupils of her eyes give away Jackie’s fear, but she bravely raises a curious eyebrow and asks ‘Where you from?’ The tone of her voice reiterates her authority as the owner of the space. The young man with a beard points to an unidentifiable space in the bushes – his hideout – ‘Over there.’

Jackie: ‘How long?’

Man: ‘Many days.’

Jackie: ‘On my land?’

Tension builds, the drama unfolding with a young man arriving uninvited into an elderly woman’s space. Will he rape her? In an earlier scene the man had managed to hide from a police officer obviously looking for him in the thick bushes and in a nearby derelict caravan.

Jackie welcomes this man into her space without asking any further questions and continues with the chores of filling up the cracks in her home. Yet her efforts seem to be in vain as more cracks appear, and there are no signs of these being erased any time soon.

The man looks on with a cold expression: it is as if he is fighting many internal wars, one of which whether to attack Jackie.

Jackie carries on, oblivious to her new situation. The man attempts to help her and uses his finger to apply the putty. Jackie tells him, in a shrill voice, not to do this with the hands. Then she begins demonstrating how it should be done. The man looks on and soon takes over the chore from her. The detail is in the close screen shots … how many of the cracks can we fill before new ones appear?

Thus, the lives and tensions of a man on the run, and a woman confined to her haven, her space, collide in a house that in itself is a character in the film. Each character has been shaken by the seismic events in their lives, and the narrative of the film begins here with overarching poetic verses from Labid’s 7th century poems, providing the viewer with some direction and understanding of the plot.

Water is a significant metaphor in the film, representing a means of cleansing what may look bad, such as the remains of the white putty on the man’s hand. He washes himself in the birdbath, raising empathy in the viewer while presenting a stark reality of those making use of what is available to them. The use of water is again present as the man and woman share the chore of watering plants on the veranda, forming a common bond and engendering trust as Jackie allows him to water her plants.

In a few scenes Jackie and the man lunch on bread and a cup of tea, without saying a word. Here silence speaks volumes as the man carries the weight of the world in his eyes, searching and looking, while Jackie is free-spirited with a single mission – to fill up the cracks in her house. She potters around the house and is shown enjoying a ‘cuppa’ with the man.

Soon they become comfortable with each other and Jackie offers him her son’s clothes, which she says are in good condition as she never throws anything out. He carefully looks at the three items and tries on the third, a jacket that he pulls over his chest, as if demonstrating that he has finally found some warmth and comfort.

The critical scenes are where Jackie asks the man his name. He is silent and gives her a searching, cold look. Suspense builds when Jackie asks him if he eats pork, presenting him with a plate of food. At this particular juncture the audience can begin to guess the man’s identity as Muslim. He hesitates, as if giving this a second thought, accepts the plate of food and digs into it, perhaps to disguise his identity.

In the scenes following, Jackie’s landline phone rings and she answers it with much trepidation while the man looks on, his face wrapped in fear. She speaks in Dutch.

Soon after the conversation is over the man declares: ‘If you tell, I kill.’ She then explains that the call was from her son who wanted to visit her on Sunday for her birthday and that she had asked him not to. The scene cuts across to where Jackie is driving away in the car and puts the car window down to tell the man, who runs over to her from the bushes, that she’s going to the shops to get cake for her birthday. She says that she has locked up the house and that he should wait for her outside.

When she returns, she finds the man gutting a rabbit that he has killed. Death brings a cold shiver through the spine and tension builds up bringing to mind all sorts of possibilities.

However, there is celebration … Jackie cuts the birthday cake alone and looks up several times with a fleeting hope and despair on her face, as if hoping for the man to reappear. She ends up eating the cake alone but the scene cuts across to her eating the rabbit stew with the man.

Silence in the scene is a killer … until Jackie quips, ‘This rabbit stew is nice’. The man smiles and nods, puts away his plate and asks her for a dance. She stands up but is looking lost … for the first time not knowing what do or say. He serenades her, looking happy and confident for the first time. To the viewer, there is an obvious change of power and a reversal of the roles. Jackie quips that she does not know how to dance this way, yet she tries. The man, becoming game, dances around her and soon the scene cuts to her bedroom where death becomes the ultimate end.

The overarching theme of this hybrid thriller, a feature film presented poetically as fiction and drama, is the crack in human lives, how we muster through the fault lines, judging and refusing others entry into our spaces and boundaries. Or if allowing them to invade these spaces, making their entry conditional with ourselves perennially on guard.

The man, who hardly speaks a word during the film, represents the repressed and suppressed self. In contrast the woman, who is presented as a strong character, is indeed weak for the outward battle she seems to be fighting against the walls she attempts to make strong. Despite her efforts, they keep collapsing before her eyes. She nurtures her giving spirit and allows the man to enter her scared space – her home and her bedroom (where he sleeps on the floor while she is in the bed). She declares that she has no fear as the spirits in the house protect her. These are the very spirits the man fears for he always finds himself in a dream … running and escaping. The woman’s contentment with the space she owns is presented like nectar in a sieve, a kind of happiness that is passing, evasive and elusive.

The dream sequence of the film is strong, creating a level of fear in the man who subconsciously sees himself as being arrested, awakening from dreams of bomber planes hovering in the skies. All these allude to the man’s reality, perhaps as an asylum-seeker, a refugee or a war victim, in search of a space or place.

At a deeper level, this search is an ongoing habit of man, always wanting more than what he can have, or manage, not finding complete satisfaction or contentment with his own situation. Although this search may be a global phenomenon through migration and movement, it is an internal battle every human being is fighting or dealing with.

Human battles end with death, which is always imminent.

Truly, the arrows of death never miss their mark – Labid.

About the reviewer

Dr. Asha Chand is a lecturer in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts at the University of Western Sydney where she teaches many units in the journalism program. . In 2006, Asha was the recipient of a national Australian Carrick Award for Excellence in Teaching. She is an academic and a journalist with a combined industry experience of more than 29 years. She migrated to Australia in 1998 and joined the UWS journalism program in 1999. Her research focuses on global comparisons of how traditional and modern media intersect, and the role new media plays in facilitating migration and marriage to maintain cultural identities in modern and traditional societies