Australia’s Welfare Discourse and News: Presenting Single Mothers

Emily Wolfinger

University of Western Sydney (Australia)

Abstract

Welfare reform has been high on the nation’s agenda since the 2014-15 federal budget delivered a raft of proposed reforms. This essay critiques the single mother in welfare news and debate from a critical point in welfare history – the 1980s. It draws on key social and political events, as well as feminist perspectives, in framing its arguments. It is primarily based on Australian research of media representations of single mothers during the announcement and implementation of the Gillard government’s cuts to the single parent pension. The analysis is both descriptive and explanatory, as it presents and contextualises findings in relation to current political debate regarding welfare dependency and the culture of this dependency. It also explores how the transition from ‘passive’ to ‘active’ measures in welfare from the 1980s has played out in media depictions of single mothers.

Introduction

The Abbott government has received widespread criticism for its proposed changes to the welfare system in the 2014-15 federal budget and has encountered a number of stumbling blocks to their implementation. Perhaps one of the biggest single recent changes to welfare policy, however, occurred in January of 2013 when the former Gillard Labor government moved recipients of Parenting Payment (Single), whose youngest child had turned eight, onto the lower Newstart payment. This policy signaled a critical shift in Labor welfare policy with Labor imposing its harshest limitations yet to welfare subjects. These reforms form part of a decades-old move toward increasingly paternalistic and punitive welfare measures that seek to increase the obligations of a range of welfare recipients while reducing the responsibilities of government (Hamilton, 2012; Mestan, 2014).

Over the years, the various changes have been underpinned by a discourse relating particularly to single mothers. The essay critiques the portrayal of single mothers in the welfare debate and in welfare news, arguing that, while single mothers continue to be the targets of condemnation, the discourse on single mothers has shifted with major political and social changes. Changing ideas about women’s roles and capabilities, and the appropriateness of mothers’ dependency, have paved the way for welfare reforms that have subjected single mothers to increasingly punitive and paternalistic policy measures. In turn, these ideas have facilitated a new kind of stereotype of single mothers – that of ‘welfare dependent’, a term that carries a range of negative connotations.

These arguments are supported by preliminary Australian findings on media representations of single mothers during the announcement and implementation of the Gillard government’s sole parent pension cuts. With this in mind, the essay documents a thematic and discourse analysis of single mothers identified in Daily Telegraph news articles and episodes of A Current Affair during the welfare policy timeframe. The discussion explores how the transition from passive to active welfare measures has played out in mainstream media depictions of single mothers, arguing that two competing discourses of welfare emerge through the content. It should be noted that the essay focuses on single mothers rather than single parents given that, beyond the fact that most single parent primary carers are women, much of the discourse and stereotyping around single parents is rooted in gender. This is particularly evident in media portrayals of various welfare debates – both at the historical and contemporary levels. The next section of the essay explores this paradigm.

Single mothers and modern welfare reform

The ideological paradigm behind much modern welfare reform is neoliberalism (De Goede, 1996) with its emphasis on economic participation. While individuals are expected to fulfil certain family and community responsibilities under neoliberalism, their primary responsibility is to the economy and the state as ‘market roles have been elevated as the most essential civic roles’ (Schram, Soss, Houser & Fording, 2010, p.740). The neoliberal imperative of individual responsibility is fundamentally incompatible with dependency work, yet this market-centric logic also applies to those who care for children alone (Huda, 2001). It was under the prime ministership of John Howard that the limitations applied to unemployment benefits were extended to those receiving the single parenting and disability payments (Mestan, 2014).

However, neoliberal economic ideology has not been confined to the conservative side of politics in Australia. The Rudd government also tightened the conditions under which parents received welfare benefits, signaling a Labor-Coalition convergence in the ‘extension of obligations and penalties to other recipient groups’ (Hamilton, 2012, p. 464). Further, the Gillard government’s welfare to work reforms, introduced on January 1, 2013, signaled another leap in Labor welfare policy, with Labor imposing its harshest limitations yet on welfare subjects other than Newstart recipients. The policy moved recipients of Parenting Payment (Single) onto the lower Newstart payment once their youngest child turns eight. The Gillard government’s reforms marked one of the biggest single changes to welfare policy affecting single parents, building on the Howard government’s 2005 Welfare-to-Work policy, which required single parents on welfare to be searching for part-time work by the time their youngest child was six (Staley, 2008). More recently, the Abbott government’s proposed welfare changes also extend former Prime Minister Howard’s legacy of welfare reform. These restrictions have broad application and include those receiving unemployment, disability, parenting, and carer benefits. Even so, the Abbott government has encountered a number of obstacles to changing the payment policy, with the first set of welfare measures approved as late as mid-November this year.

Ironically however, one of Tony Abbott’s ‘signature policies’, the proposed paid parental leave scheme (PPL), is also focused on increasing Australia’s productivity, encouraging women to remain in the workforce while also supporting them in the months after the birth of a child. However, the language used to promote the PPL stands in stark contrast to Treasurer Joe Hockey’s 2014-15 budget speech. During the budget announcement, Hockey justified proposed changes in terms of ‘national interest’, warning that ‘the age of entitlement is over’ (Hockey, 2014). By contrast, the Abbott government is pushing to make paid parental leave a ‘workforce entitlement’ that supports ‘women of … calibre’ to have families and careers (Department of Human Services, 2013; Farr, 2013). Indeed, while working mothers, particularly higher earning mothers, stand to gain from the Abbott government’s paid parental leave policy, the situation of poor single mothers would deteriorate under the proposed budget changes. According to a September analysis of the budget, women from low-income households – namely, single mothers – are expected to experience the greatest financial losses if some of the proposals are implemented (Hutchens, 2014). This is despite the government’s assurance that an aim of the budget is to ensure the vulnerable and disadvantaged are assisted into the future (Hockey, 2014).

Similarly, thousands of women have been, and are yet to be, affected by the Gillard government’s welfare-to-work reforms. Single mothers are a sizeable social group – one in five Australian families with dependent children are headed by single parents, four in five of whom are women (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2011; ABS, 2012, December 11). The welfare policy potentially affects 41.3 percent of all households headed by single parents with dependent children, as these households rely on welfare as their main source of income (ABS, 2012, March quarter).

The Gillard government’s wide-reaching policy was highly criticised when it was announced as part of its 2012-13 budget. Significantly, there were warnings that the policy may violate human rights as defined by the UN (AAP, 2013). Another criticism was that women might be less likely to leave abusive relationships if they cannot afford to support themselves or their children. Alternatively, women may return to abusive relationships for this reason. Domestic violence statistics, in combination with employment statistics, show the frightening potential for such stories 1. Alarmingly, the majority of women who have experienced partner violence have children in their care. In the Personal Safety Survey (as cited in Campbell, 2011), 61% of women who had experienced violence by a previous partner said that they had children in their care at some point during the relationship.

Morally irresponsible, economically irresponsible: Shifting discourses on single mothers

According to international academic literature, three representational categories of single mothers have dominated mainstream media since the 1980s – a critical decade in welfare debate across the Anglo-liberal world. Welfare dependency and poverty are common themes in media representations of single mothers, reflecting the concerns of proponents and opponents of modern welfare reform, respectively. The third category of stereotypes emphasises the moral character of single mothers, and can also be attributed to welfare discourse. As most of the media examined in the literature is American, many of these representations reflect the political, social and historical realities of the US where explicit stereotypes of single mothers as immoral persist (Staley, 2008). Staley argues that in modern Australian politics, where reform tends to be based on research, such language is not well tolerated 2.

‘Welfare queen’ is an infamous stereotype of single mothers that arose in the US during the 1980s (Bullock, Williams & Wyche, 2001; Hancock, 2003; Kelly, 2010). While ‘welfare queen’ was used to promote the perception that most (usually black) American single mothers commit fraud or ‘cheat the system’, the label ‘welfare mother’ derives from paternalistic policy in the 1990s, the language of which was used to construct a perception of single mothers as welfare subjects who must be closely monitored due to their incompetence (Kelly, 2010). Drawing on research by Jackson, McLaughlin, Sidel, Wilcox and others, Bullock et al present some common stereotypes of single mothers in mainstream US media during the 1990s: ‘…women receiving public assistance are stereotyped as lazy, disinterested in education and promiscuous’ (2001, p. 230). An alternative image of single mothers as ‘uniformly poor, struggling, oppressed and unhappy’ also gathered momentum around this time (Morris, 1992). Atkinson, Burns and Oerton (1998) found in their analysis of UK media that single mothers were commonly depicted as never-married, young and socially irresponsible or ‘scroungers’ and ‘benefits driven’. More recently, Kelly found that single mothers receiving welfare assistance were explicitly stereotyped as childlike, hyper-fertile, lazy and bad mothers. Such images work to define single mothers as ‘outsiders’ who ‘deviate from middle class values and norms’ (Bullock et al, p. 231).

In Australia, the denigration of single mothers as morally irresponsible harkens back to pre-Federation times. In her book Single Mothers and Their Children: Disposal, Punishment and Survival in Australia, Swain (1995) shows how stigma was reinforced in terms used to describe single mothers: ‘ ‘Harlots’ and ‘strumpets’ became ‘fallen women’, ‘unmarried mothers’ and more recently ‘single parents’’ (p. 2). Swain goes on to say that the term ‘single mother’ was adopted in the 1960s in Australia by self-help groups, as a replacement for ‘unmarried mother’, but that it continued to assume many of the negative connotations it sought to quash. In her classic work, Damned Whores and God’s Police: The Colonisation of Women in Australia, Summers (2002) argues that, over time, ways of defining women have shaped their behaviour – what they can and cannot do. She notes with reference to the title, that from the early days of colonial Australia women were perceived as either ‘damned whores’ or ‘God’s police’. While the latter category of women, usually wives and mothers, were entrusted with moral guardianship, perceived as virtuous and of good character, the former category were women who had gone against the moral order, including unmarried mothers who were ‘[t]he most visible single symbol of the bad girl’ (p. 51). While single mothers ‘conformed to part of the God’s police prescription by being mothers … they [had] transgressed another part of it by rejecting marriage’ and were cast as whores (p. 494). Women could reclaim membership to God’s police if they married before the birth of their child, or concealed their pregnancy in religious homes, which resulted in relinquishment of their child for adoption.

Old perceptions of single mothers as whores and unnatural women contrast sharply with representations of mothers and wives as asexual, compliant, nurturing and sacrificial. Such stereotypes have their root in ideas that motherhood was the ‘most important public service’ that a woman could perform; that working outside the home was acceptable if it was volunteer work; that the role of mothers was to see to the spiritual nurturance of their children, while husbands attended to their physical nurturance; and that, more than housekeepers, women were homemakers (Summers, 2002). The implication of these stereotypes of motherhood was that female sexuality and independence were abnormal and perilous to society, and hence something to be controlled:

The idea of wives as sexually active, and moreover, sexually interested creatures, was abhorrent to the God’s police stereotype…[and] [e]ven more so was the notion of single women ‘losing their virtue’ since virtuous wives were seen to be the foundation of ‘the family’ and of the nation (p. 368).

Stereotypes of virtuous motherhood persist and these are reflected in the expectations and experiences of modern-day mothers who work, keep house and care for children – a workload that frequently inhibits sexuality and demands much personal sacrifice. In modern Australia, single mothers on welfare contravene the new, economic moral order by ‘burdening’ society with their dependency. Their decisions around family and work, rather than their personal moral choices, are the new object of social control.

It was in the 1980s that the focus began to shift from the ‘problem’ of the single mother to the ‘problem’ of welfare dependency whereby single mothers’ reliance on welfare, rather than their marital status, was deemed the social problem. While society has entered an age of liberal sexual attitudes and changing family structures where explicit moral judgments are less tolerated, the denigration of single mothers persists via a construction that sees them as flawed economic citizens. As Bauman (1998) states:

… individuals unable or unwilling to undertake these ‘normalized’ acts of consumption [such as participating in paid work] become conceptualised as flawed consumers … (p. 614).

Thus, welfare dependence is personalised with social pathologies (Shaver, 2002). Despite major advances in social movements, the image of the single mother as morally irresponsible remains in the collective consciousness of society, even as the single mother has become synonymous with welfare recipient.

The emphasis on welfare dependency in single mother discourse emerged with the adoption of active measures of welfare across the advanced industrial world from the 1980s, which were founded on the ‘active society’ concept propagated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (Shaver, 2002). These measures came about in response to the idea that the welfare system had become a source of social problems, rather than part of their solution. Active measures which sought to fulfil longer term objectives, contrasted sharply with earlier passive measures of welfare which were introduced in the post-war era of full employment in order to maintain a basic level of economic well-being. Under these changes, welfare has been ‘transformed from a limited social right to support provided on condition’ where, increasingly, market and family are considered the favoured institutions for social support (Shaver, 2002, p. 332). The language that has accompanied this transformation places ‘a much stronger emphasis on the active, responsible citizen or ‘entrepreneurial self’ and has been accompanied by a discourse of blame for social misfortune’ (Hamilton, 2012, pp. 453-54). According to Huber and Stephens (2001), welfare state retrenchment can be attributed to unemployment. They argue that globalisation, or the opening up of economies to foreign trade, has had a significant impact in Australia and New Zealand where, historically, economies had been highly protected.

Stereotypes of single mothers as economically irresponsible and a burden can also be linked to women’s increased presence in the workforce. While feminists like Alice Rossi (as cited in Pascoe, 2006) theorise that it is the devaluation of mothering that reduces perception of the mother’s contribution to society, it can also be argued that women’s increased participation in paid work has resulted in new and emerging views of women’s roles and capabilities. Indeed, as more mothers entered the workforce, the ‘breadwinner model’ of welfare that viewed mothers as appropriately dependent, and hence appropriately powerless, was gradually replaced by a model that promoted employment for all (Misra, Moller & Karides, 2001; Shaver, 2002) 3. Therefore, mothering has not been so much devalued as demoted to just one activity in which women participate. Chesney-Lind (as cited in Schram et al, 2010) argues that ‘the replacement of gender difference with sameness [has] led to the more punitive treatment of women’ (p. 743) by governments. Single mothers are particularly at risk of punitive policy given they are more likely than coupled mothers and childless women to rely on welfare as their main source of income.

The role of media in the welfare debate

As western society’s dominant institution, the media plays a powerful role in people’s lives by informing, raising awareness and shaping public attitudes. Bullock et al (2001) point out that the power of the media to influence audiences may be particularly strong when highly politicised issues such as welfare policy are concerned. In reporting on government and policy, it is argued the media’s power lies in the selection of reported issues (Ross & Nightingale, 2008). The relationship between cause and effect however, is not simple. The notion of media influence (powerful effects theory) in which the media message is the cause, and public opinion the effect, has largely been rejected by communication scholars including McLuhan, Barthes and Hall (as cited in Griffin, 2000).

Bullock et al (2001), however, make the point that highly politicised issues are likely to reflect the ideas of dominant (powerful) groups in society, leaving other (less powerful) groups at risk of stereotyping and devaluing by the media. Perkins (as cited in Lacey, 2009) categorises six groups that are prone to stereotyping, including isolated and pariah groups. As members of groups who have been marginalised in society, single mothers are commonly under-represented and, therefore, stereotyped within the media. The social identity theory of Tajfel and Turner (as cited in Schwartz, Luyckx & Vignoles, 2011) also offers insight into why particular groups are stereotyped. According to this theory, people tend to exaggerate the differences and similarities between and within groups, which can lead to prejudice and the formation of ‘in’ groups (dominant groups like the mainstream middle class) and ‘out’ groups (marginalised minority groups like single mothers).

Stromback (as cited in Finnemann, 2011) offers further insight into why particular groups are stereotyped within the media. He is more specific than Bullock et al when he argues that the selection and presentation processes of news are geared toward serving market interests, or the interests of dominant groups within the constraints of media format. By this logic, welfare policy, for example, may be presented in terms of how it affects the dominant group (that is, cost to the taxpayer) rather than the minority group it directly impacts. Stomback breaks down these processes of newsmaking, providing a useful tool through which to understand media representation: these are known as storytelling techniques. Among these techniques he includes ‘simplification, polarization, intensification, personalization, visualization and stereotypization, and the framing of politics as a strategic game’ (p. 71). He says the media use these techniques:

… to take advantage of their own medium and formats [for example, simplification], and to be competitive in the ongoing struggle to capture people’s imagination [for example, intensification] (Stomback as cited in Finnemann, 2011, p. 71).

An aspect of the news cycle that works to the advantage of groups like single mothers, is that it is perpetually seeking new material for stories, particularly in this age of the 24-hour news cycle (Misra et al, 2003).The ideologies of powerful institutions like government inform dominant discourse. Lacey (2009) argues that ‘the audience is free to choose whether or not to use the offered discourse’ (p. 119). That is, the meaning we derive from a text depends on the ideas or discourses we bring to it, and how we decode it. By this logic, the communication of dominant discourses within the media can work to reinforce the ideas of the majority of the audience while the inclusion of alternative discourses may be ineffective in communicating meaning. In this context discourse is defined as the communication of ‘systematic frameworks for understanding that are socially formed’ (Macdonald, as cited in Lacey, p. 114). Thus, discourses limit and regulate what can be communicated about a given topic (Foucault, as cited in Kelly, 2010). While the audience may bring their own perspective to a given text, discourse occupies an important role in modern society as it serves to ‘shape’ ways of understanding. According to Fairclough (as cited in de Goede, 1996), ‘the exercise of power in modern society is increasingly achieved through ideology, and more particularly through the ideological workings of language’ (p. 320).

Following on from this, the language used in mainstream media, therefore, acts to reflect sexist constructs of family and work (Huda, 2001), reinforcing patriarchal and neoliberal ideologies. Media representations of single mothers as vulnerable, struggling, unhappy, economically irresponsible, a burden and morally irresponsible promote the traditional patriarchal family unit as ideal (Rothman, 2002). Social commentator and journalist Bettina Arndt has been an outspoken critic of single parent families, often leveling criticism at women for the phenomenon. In May 2014 she spoke at Sydney’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas about how ‘some families [two-parent families] are better than others [single-parent families]’. In the past she has argued that children do best with two parents and worst with one parent, decried women’s choices to have children outside of a relationship, and said that a bad marriage may be better for children than a ‘good’ divorce (Arndt, 1998; Stefanovic & Wilkinson, 2014). However, while a happy marriage clearly benefits children, the reality is that marriage often hides women’s poverty, and the structures that perpetuate it. Rothman says that in a patriarchal society, ‘[m]otherhood … is what mothers and babies signify to men’ (p. 124). In other words, the value of this role is determined by men. In the patriarchal neoliberal construct, the value of economic participation is privileged over the caring work of mothers. In failing to critique the neoliberal paradigm, or the failure of the market to facilitate single mothers’ economic self-sufficiency, mainstream media reinforces men’s economic and social hegemony at the expense of poor single mothers and their children.

While the language used by popular forms of old media commonly promotes dominant discourses, the rise of new media has amplified alternative voices, allowing people from all social levels to express themselves in ways never before possible. As such, the influence of the media in storytelling is diminishing, according to Finnemann (2011):

The very notion of the media as a uniform general agenda setting agency which defines the framing of the storytelling in society is giving way to a more complex system of media that allows the citizens to compose their own individual media menus and tell a wider spectre of stories in a richer set of genres…Old media still have a say [b]ut they have to accommodate as much as they define (p. 86)

For example, news and current affairs programs are increasingly promoting their stories through social media – facilitating the communication of a diverse range of opinions – while news sites frequently invite readers to comment on stories. Indeed, many garner ideas and participants for stories via social media. These examples of audience participation through new media raise questions about the influence of new media in shaping public discourse, especially with regards to marginalised groups. McLuhan (cited in Griffin, 2000) – the Canadian theorist who famously coined the aphorism ‘the medium is the message’ (Gordon, 2010, p. vii) – suggested that the channel of communication, not the media message, ‘changes the way we perceive the world [because] the dominant medium of any age dominates people’ (p. 317). This argument is particularly true of new media, which has the capacity to occupy every space and waking moment, providing a platform for instant communication to any number and range of readers.

Despite the decentralised culture of the internet, most Australians are still accessing mainstream media content, whether online or via older forms of media, while media ownership is more concentrated than ever before. According to the Australian Communications and Media Authority (2013), recent rapid growth in data usage can be attributed to the rapid take-up of online content services, with nearly 8 million people accessing professional content services like catch-up TV, video on demand and IPTV in the six months to May 2013, an increase of 52 per cent compared to May 2012. In considering these realities, it is unsurprising that some scholars are highly sceptical of the power of new media, despite its pervasiveness. Ampuja (2011) says that Manuel Castell’s argument that the power of political elites and corporations to influence public opinion is negated by ‘the power of flows’ or the ‘out-of-control’ information networks of the internet, is flawed, arguing that:

[i]t is … rather bold to state that information networks are ‘truly out of control’, given that corporations and states still have enormous resources in their hands – much more than, say, individual bloggers – to influence public perspectives on important social issues through different types of public relations activities (p. 290).

Ampuja further argues that theorists such as Castells fail to take into account the capitalist dynamics in their analysis of new media, instead analysing globalisation as a new phenomenon ‘that is driven by the speed of new media and communication technologies’, rendering globalisation theory ‘subservient to the still ongoing global neoliberal hegemony’ (p. 298).

Single mothers in Australian welfare news

There is currently no study that exclusively examines Australian media representations of single mothers, making this the first study of its kind. One explanation for this is that Australian welfare policy has been more generous and less punitive than its American counterpart, and its accompanying discourse has reflected this (Shaver, 2002). The American studies cited earlier mention the passing of a crucial piece of US legislation – the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) – that promised to ‘end welfare as we know it’ (Bullock et al, 2001; Hancock, 2003; Misra et al, 2003; Kelly, 2010). Indeed, the bill ended welfare as an entitlement program, requiring welfare recipients, including single mothers, to begin working after two years of receiving welfare benefits. Such radical reforms have been accompanied by a discourse on single mothers as morally bad (Staley, 2008).

In order to study media representations of single mothers from the announcement and implementation of the Gillard government’s cuts to the single parent pension, I conducted a thematic analysis of the messages conveyed in 17 Daily Telegraph online and print news articles and eight episodes of Channel Nine’s A Current Affair, published/aired between 4th May 2012 and 20th January 2013. The thematic analysis was based on the approach advocated by Marks and Yardley (2004), employing inductive, deductive and prior-research driven codes to interpret the data. Codes also flowed from the questions that this research sought to answer. Thematic analysis was selected over other methods of qualitative analysis because it is a flexible, interdisciplinary method that offers a first step in data analysis (Harvard University, 2008). As a process of encoding qualitative data, thematic analysis is suited to revealing representations of single mothers, as representations are mostly made in qualitative terms.

In order to uncover the linguistic and contextual meanings of the data, some discourse analysis of the content was also conducted. Thus, the discourse analysis provided can be more accurately described as critical discourse analysis as its focus is not on the linguistic aspects of texts, although this forms part of the analysis (Hamilton, 2012). In addition to looking at the context or broader meanings of data, some practices discourse is provided, extending on this essay’s examination of news making processes. Discourse practices analysis involves examining the ways in which texts are produced by media workers, and the institutions in which they operate (Fairclough, 1995).

The study coded news articles for representations of single mothers (‘burden’, ‘irresponsible’, ‘dishonest’, ‘struggling’, ‘oppressed’ and ‘vulnerable’); speaker perspective (‘single mother’, ‘politician/bureaucrat’, ‘advocate/activist’, ‘expert/professional’ and ‘other’); and how the stories framed single mothers (sympathetic, unsympathetic and neutral). Representation codes were primarily drawn from recent welfare policy research through a process of translating common themes in discussion of active and passive welfare (such as ‘dependency’, ‘social pathologisation’ and ‘entitlement’) into words that may be associated with single mothers (for example, ‘burden’, ‘irresponsible’ and ‘oppressed’). The process was guided by an initial reading of news articles from The Daily Telegraph and transcribed episodes of ACA. During the analysis, pre-analysis themes were confirmed and coding descriptions were developed. For example, the code ‘irresponsible’ resulted from a process known as splicing, which ‘involves the researcher thinking through what codes can be grouped together into more powerful codes’ (Marks & Yardley, 2004, p. 10). It was impossible to incorporate all codes into a final analysis. Similarly, themes were also linked or clustered into groups to demonstrate the sequential relatedness of sets of codes – for example, ‘frame-single mothers-sympathetic’.

Talking about single mothers: Victims or delinquents?

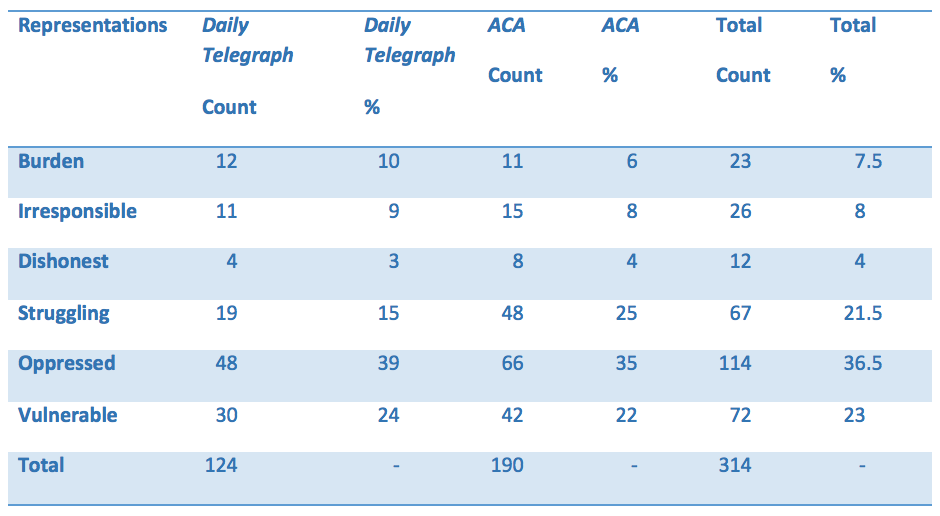

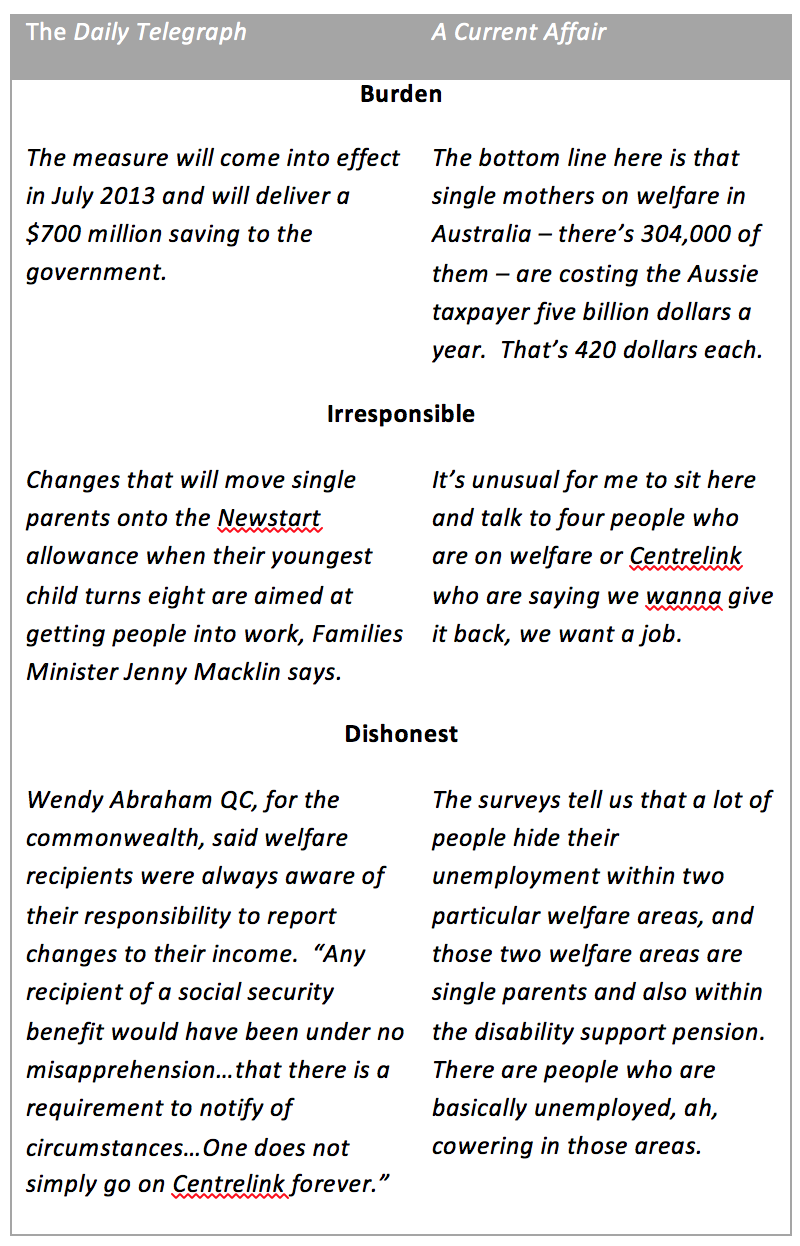

My study found that single mothers are constructed as economically flawed citizens in one of two ways. The image of single mothers as described by Morris (1992) – ‘uniformly poor, struggling, oppressed and unhappy’ – was the dominant image of single mothers across The Daily Telegraph articles and ACA episodes (see Table 1). Themes of the active welfare era, which include activity, participation, dependency, fraud and social pathologisation (Shaver, 2002), were reflected in an alternative image of single mothers as irresponsible, a burden and, to a lesser extent, dishonest because they do not participate in paid labour or they engage in unlawful and fraudulent behaviour. The representations underpin two key arguments around the welfare cuts: that single mothers are entitled to and require welfare support, and that welfare is a temporary albeit undesirable form of income support.

Table 1: Representations of single mothers by media source

Welfare, poverty and single mothers: Three key perspectives

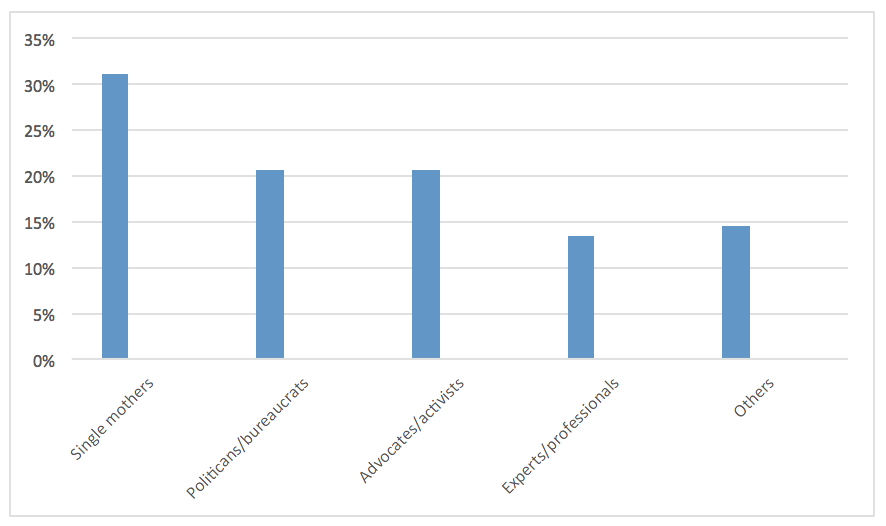

Three critical perspectives emerge through the representations of single mothers: those of single mothers, politicians/bureaucrats and advocates/activists (see Figure 1). The first is that the issue of welfare was framed in terms of responsibility for poverty by politicians/bureaucrats and advocates/activists. Second, single mothers talked about the effects and causes of poverty according to their lived experiences and third, the absence of comments from experts/professionals meant the content lacked a ‘voice of authority’ to weigh in on the welfare debate.

Figure 1: Perspectives across media sources

While advocates/activists placed the onus of responsibility for poverty onto governments, Labor politicians/bureaucrats and other proponents of the cuts, indicated that single mothers were responsible for their own welfare and the welfare of their families. Thus, both advocates/activists and politicians/bureaucrats defined poverty in terms of responsibility. According to Hall (as cited in de Goede, 1996), the definition of a social problem like poverty limits or regulates all subsequent discussions of the problem. De Goede notes that social problems are similarly defined today by both progressives and conservatives. She explains that in order to have a voice in the political debate, US progressives – who have lost their ‘theoretical [premise] and popular [appeal]’ (p. 317) – now often accept the conservative view of social problems, even though they may propose different policy solutions. This is also true of Australian politics where the problem of welfare dependence is defined in terms of economic participation, (rather than disadvantage, for example), by the both the Coalition and Labor. However, Australian policy solutions to welfare dependency (for example, punitive measures) are merging across the major political parties.

Poverty as the responsibility of government

Advocates/activists were most likely to present single mothers as vulnerable and were vocal in their criticism of the cuts, arguing that it is the responsibility of the government to support single parent families. As such, they did not mention the structural and circumstantial difficulties faced by single mothers in attaining financial independence. The comments of advocates reflected a discourse of welfare that views government benefits as a social right whereby the wellbeing of subjects is promoted. This discourse of welfare closely resembles the ideas of passive welfare, to be explored later in this essay. In the following excerpt from ACA, Therese Edwards from the Council of Single Mothers and Their Children talks about the negative impact of the cuts on single mothers and their children, portraying single mothers as helpless and governments as responsible for the welfare of their families:

These cuts will result in women losing their homes, having difficulty in maintaining the school for their children. Certainly, food becomes an issue; healthy, nutritious food becomes a luxury rather than a daily affair’ (Grimshaw, 2012, December 19).

While advocates commonly stressed the financial implications of the cuts, comments like this talked about the broader implications of the cuts, such as effects on housing security, education of children, and health.

Poverty as the responsibility of individuals

The finding that politicians are most likely to depict single mothers as irresponsible is significant, yet unsurprising, given the increasing emphasis on individual responsibility in welfare reform. In the opening line of the following excerpt from the article, ‘Single mum tough love to save $700m EXCLUSIVE ’, Labor leader Bill Shorten (as cited in Benson, 2012) implied that single mothers avoid paid work. Despite his use of the word ‘supported’, which suggests that single mothers require assistance in transitioning into work, he failed to adequately acknowledge the challenges of these women around employment:

We believe that, once children are at school, parents should be encouraged and supported back into the workforce. A job is essential to a family’s wellbeing and helping them make ends meet. Public income support ideally should be a temporary measure and should not be a disincentive for people finding paid work.

Mestan (2014) argues that since at least the 1990s, Australian welfare policies have been highly paternalistic, involving compulsion based on benevolence. Bill Shorten’s statement, contextualised by the policy, also suggests that single mothers require paternalistic direction in order to transition from welfare to work. That is, despite his careful use of the words ‘encouraged’ and ‘supported’, the policy involves compulsion as single parents are automatically moved onto Newstart allowance once their youngest child is eight. Furthermore, in talking about employment and wellbeing, he provided the justification for compulsion: the policy advances the interests of single mothers.

In another article, titled ‘Changes will encourage work: Macklin’ (Fogarty, 2013), Labor MP Jenny Macklin inferred that single mothers are irresponsible for not setting a good example to their children with regards to a work ethic. She also indicated that poverty has an individual cause and is cyclical. She suggests that paid employment is the solution to poverty despite the challenges of raising a family on a low to average single income. Again, she used the word ‘support’, even though the policy is paternalistic and punitive:

Unfortunately, we have far too many children growing up in families where nobody is working. We want to do everything we possibly can to support families to go out to work and hold down a job (Fogarty, 2013).

Like Shorten, Macklin failed to acknowledge the difficulties many single mothers face in both attaining and holding a paid job, such as the cost and availability of childcare. While availability of childcare is also an issue for couple mothers, a study by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) (2002) found that the circumstances of single mothers put them at a greater disadvantage in securing employment, but that the presence of children has a similar impact on the employment of single and couple mothers (couple mothers are frequently the primary caregivers to their children). The lower employment rate of single mothers is partly attributed to differences in the characteristics of the two groups, such as level of educational attainment (34.4 percent of couple mothers surveyed in the study had a post-secondary qualification, compared to 25.4 percent of single mothers). Most significantly, two thirds of the employment gap can be explained by the finding that variables such as low level of educational attainment, speaking English as a second language and having poor spoken English, have a greater negative impact on single mothers than couple mothers.

Personal accounts of poverty

The stories of single mothers portrayed them as struggling, either financially or physically, and oppressed by personal circumstances, government and society. Single mothers were the only group, besides experts/professionals, to talk about structural and circumstantial conditions of poverty other than unemployment and the welfare policy. Discussion of the causes of poverty were both implied and explicated, and included issues such as: the challenges of single motherhood and finding suitable employment; the cost of living; employment and housing discrimination; and the devaluing of motherhood.

In the article, ‘Single mums slam Macklin comments’, single mother Cate Flaherty expresses her frustration over the impending welfare policy, highlighting the effects it will have on working single mothers and how it devalues their social contribution (Yosufzai & Jones, 2013). By implication, she portrays single mothers as oppressed, suggesting that the government is victimising working single mothers in particular:

As a single mother who has always worked part-time and raised polite, considerate children, I feel that I am now being treated as somebody who adds no more value in society than some junkie who sits on the couch all day.

Media analysis of the issues raised by single mothers, and single mother poverty generally, was missing from the content, with some exceptions. In the ACA episode titled ‘We want work’, a group of single mothers struggling to find work was interviewed. Throughout the episode, discriminatory employers and a flawed welfare system were blamed for locking women out of the workplace and into a life of welfare dependency (Grimshaw, 2012, May 23). While these points were mostly communicated through the voices of single mothers, they were recurring themes. Even so, the reporter undermined the women’s stories through the use of the word ‘claim’ in the following excerpt:

These single mothers claim [my italics] the system has locked them into a life of dependency on benefits, and discriminatory employers have locked them out of jobs.

However, interviewee and social analyst Mark McCrindle acknowledged the struggles of single mothers in finding work and proposed a solution to the problem:

The government can step in with more of these incentives to encourage those employers to take on people in these situations.

Other stories focused on recent concerns such as rising electricity prices and the rising cost of living in illuminating single mothers’ experiences of poverty, however, longstanding problems such as gender inequality and child care costs and shortages, for example, were not acknowledged by journalists. In providing a limited analysis of single mother poverty, the media examined here reinforces stereotypes of single mothers.

While single mothers themselves provided some analysis of the sources of their poverty, most of their comments focused on the effects of the welfare cuts and their experiences of struggle. Discussion of the causes of poverty was usually brief. These mostly simplistic accounts ignored the reality that the lives of single mothers, and the issues facing them, are complex and varied, suggesting that representations were largely constructed by journalists. The experiences of these women were mostly reduced to a single tale – one of hardship and oppression by government – yet the causes of poverty are more complex than those suggested in these stories, and cannot be adequately explored in one or even a series of personal accounts (Lens, 2002). These mostly narrow representations can be attributed to limited space and other news production constraints, as well as the news gathering practices of journalists ‘where the sensational wins over the mundane and the real’ (p. 12).

Single mothers who appeared in the episode ‘We want work’, also told another story of poverty – one in which they disparaged other welfare recipients, thereby engaging in the political rhetoric of their adversaries (Grimshaw, 2012, May 23). In the following comment, one single mother gives credence to stereotypes of welfare recipients as lazy, irresponsible and undeserving, thus separating herself from other welfare recipients:

There are so many people out there who don’t deserve to be on welfare, for starters. They don’t wish to look for a job. Then you’ve got people like us who are wanting a job, and nobody will hire us.

Lens (2002) says that 30 years of research has demonstrated that recipients are not untouched by stereotypes, often internalising them or ignoring their own experiences in denigrating other recipients. She argues that this is because they lack ‘social supports and alternative frameworks for interpreting their experiences and realities’ (p. 14). Alternative frameworks may include critiques of capitalism.

Story framing and language

If news media presentations of an issue are any indication of societal attitudes, Australians are relatively tolerant toward single mothers. The statistic that most Australian single mothers are separated and divorced (ABS, 2007) 4, combined with the social proclivity toward divorce, may explain the finding that most stories were sympathetic toward single mothers (17 of 25 stories). Indeed, stories that were framed sympathetically were both explicit and implicit in their criticism of the welfare cuts. Nevertheless, single mothers were problematised across both media sources, presented as either a drain on society or as powerless.

Moreover, negative representations from the ACA episodes were often explicit (see Table 2), while many ACA excerpts coded as ‘struggling’, ‘oppressed’ or ‘vulnerable’ in fact patronised single mothers, subtly reinforcing negative stereotypes of them. Indeed, on a surface level the stories appear to be sympathetic toward single mothers, but layers of meaning are embedded in the comments of reporters as well as interviewees. For example, the following quote depicts the single mother in question as struggling, but the connotative use of the phrase ‘government handouts’ negatively reinforces her status as ‘dependent’:

Rebecca Farrugia is raising five kids on her own. Not an easy challenge in itself but even harder when you’re living on government handouts (Grimshaw, 2012, August 16).

In addition to being sensationalist, commercial current affairs programs like ACA also have a reputation for promoting negative stereotypes of groups such as single mothers. This example also demonstrates the subjectivity of the news making process whereby the views and beliefs of the journalist enter the story, albeit often unconsciously. As Gans (as cited in Lens, 2002) points out, this occurs though ‘the use of connotative, often pejorative, words and phrases’ (p. 10). Indeed, emotive language was used across both media sources, although for the most part it was sympathetic toward single mothers and disparaging of the welfare cuts, as evidenced by the following examples: ‘force [back into work]’, ‘payments axed’, ‘worse off [under new policy]’, ‘slashing their income’, ‘backlash [from policy]’, ‘lose [money]’, ‘pushed [off the payment]’, ‘stripped [of the payment]’, ‘salt in the wound’, ‘make ends meet’, ‘poverty line’, and ‘[cutbacks will] hit savagely home’.

Table 2: Coded comments by media source and negative representation

Discourses of welfare: Active and passive welfare themes

The modern Australian welfare system places value on the ‘moral ideas about the responsibility of citizens to be self-sustaining’ (Shaver, 2002, p. 331). Inferentially, the responsibilities of parents and carers are secondary to economic participation. Indeed, the themes of active welfare were promoted by politicians/bureaucrats as well as radio hosts and social commentators (experts/professionals) through representations of single mothers as irresponsible, a burden and dishonest. By contrast, the themes of passive welfare such as entitlement and social equality (Shaver) emerged from the statements of single mothers and advocates/activists. In one article – ‘Welfare cuts worry Labor backbenchers’ – the Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS) depicted single mothers as oppressed by government, suggesting that welfare was a social right of single mothers because it facilitates social equality:

The bill, if passed, will provide an institutional obstacle to the full enjoyment of human rights for people living in extreme poverty and increase discrimination against sole parents’ (Martin, 2012).

According to Shaver (2002), passive welfare promoted a view of social citizenship that most closely resembled T.H. Marshall’s ‘idealised vision’ (p. 332). For Marshall (as cited in Shaver, 2002), social citizenship referred to:

… the whole range from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society’.

As Schram et al (2010) point out, under neoliberalism some human rights become privileges as access to full citizenship and the rewards that they entail require participation in the marketplace (as opposed to membership under passive welfare). Those who do not fulfill their obligation to engage in paid work are negatively viewed:

[The] obligation to work and function as ‘self-sufficient’ actor in the marketplace is recast as the primary responsibility of the citizen and, indeed, as a necessary precondition for ‘moral standing’ as a member of society who merits equal respect [and] possesses full rights (Schram et al, 2010, p. 743).

Conclusion

While single mothers continue to be pathologised and problematised, this research would indicate that depictions have changed. In the past, it was the moral character of the single mother that was denigrated. More recent depictions reflect a new political concern – that of welfare dependency. This essay argues that this shift coincided with the introduction of active measures of welfare, which promote employment for all. These events can also be linked with women’s increased participation in the workforce, which resulted in new and emerging views of the capabilities and roles of women, including single mothers.

Proponents of the Gillard government’s welfare cuts justified the changes to the single parent pension by placing the onus for poverty onto single parents, pathologising them as irresponsible and a burden. Their comments ignored the challenges of sole parenthood and the obstacles to employment that these challenges entail. Rather than acknowledging these realities, many comments promoted the ‘values’ of the ‘active society’ and highlighted the ills of welfare dependency. These comments form part of a new political rhetoric around welfare which includes slogans like ‘age of entitlement’, ‘earn or learn’, ‘hand up, not hand out’ and ‘lifters, not leaners’ – all of which emphasise individual responsibility and stereotype welfare recipients.

While single mothers continue to be demonised via Australian welfare news, negative representations are not usually explicit. Moreover, the perspectives of single mothers were favoured across the content examined, and most reports were sympathetic toward this group. Even so, analysis of poverty was largely missing across the media content examined. The solutions to poverty prescribed by politicians and advocates were work or welfare, respectively. Stories across both The Daily Telegraph and ACA failed to critique the neoliberal paradigm, or the failure of the economic market to facilitate single mothers’ economic self-sufficiency, while alternative solutions to poverty were not discussed. These issues need to be communicated by the media in order to challenge messages that reinforce negative perceptions of single mothers, de-emphasise the caring roles of these women and, most critically, promote the structures that perpetuate poverty.

Notes

1 According to the International Violence Against Women Survey (as cited in Campbell, 2011), 34 percent of Australian women who had a current or former partner said they had experienced physical and/or sexual partner violence. Up to 40 percent of women said they had experienced at least one form of controlling behaviour, such as verbal abuse. Domestic violence is the leading cause of death and injury in women under 45 and current and former partners are often the perpetrators. In Australia, at least one woman is murdered a week by a former or current partner (Doughty, 2014).

2 In February of 2014, Conservative backbencher Cory Bernardi received wide criticism for decrying a link between ‘non-traditional families’ and higher levels of ‘criminality among boys and promiscuity among girls’ (Porter, 2014), demonstrating that old attitudes toward single mothers are not well tolerated in Australia.

3 Welfare benefits for single mothers, which were introduced in 1973 under the Whitlam government, were originally predicated on this model of welfare.

4 Fifty five percent of single parents of children under 15 years are divorced or separated from a registered marriage, while a large proportion of never-married parents were previously in a de facto relationship (Ibid.).

References

AAP (2013, March 3). Gillard snubs UN on single parent welfare. The Australian. Retrieved from http://www.theaustralian.com.au

Ampuja, M. (2011). Globalization theory, media-centrism and neoliberalism: A critique of recent intellectual trends. Critical Sociology, 38(2), 281–301. doi: 10.1177/0896920510398018.

Arndt, B. (1998, February 14). And baby makes two. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.bettinaarndt.com.au/resources/articles/and-baby-makes-two/

Atkinson, K., Burns, D. & Oerton, S. (1998). ‘Happy families?’: Single mothers, the press an d politicians. Capital and Class, 22 (1), 1-11. doi: 10.1177/030981689806400101.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2007). Australian social trends (no. 4102.0). Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/F4B15709EC89CB1ECA25732C002079B2?opendocument

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012, March quarter). Life on ‘Struggle St’: Australians in low economic resource households. In Australian Social Trends (No. 4102.0). Retrieved from http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/LookupAttach/4102.0Publication04.04.121/$File/41020_ASTMar2012.pdf

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012, December 11). Family and community [data set]. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/BE6B2842A6549A7FCA257ACC000E2A23?opendocument

Australian Institute of Family Studies (2002, May). Determinants of Australian mothers’ employment (Research Paper No. 26). Melbourne: Gray, M., Qu, L., de Vaus, D. & Millward, C.

Australian Consumer and Media Authority (2013). Australia’s mobile digital economy – ACMA confirms usage, choice, mobility and intensity on the rise. Retrieved from http://www.acma.gov.au/theACMA/Library/Corporate-library/Corporate-publications/australia-mobile-digital-economy

Australian Institute of Family Studies (2011). Families then and now: 1980-2010. Retrieved from http://www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/factssheets/fs2010conf/fs2010conf.html

Bauman, Z. (1998). Work, consumerism and the new poor. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Benson, S. (2012, May 4). Single mum tough love to save $700m EXCLUSIVE. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved from the ProQuest Australia & New Zealand Newsstand.

Bullock, H. E., Williams, W. R. & Wyche, K. F. (2001). Media images of the poor. Journal of Social Issues, 57 (2), 229-246. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00210.

Campbell, R. (2011, February). General intimate partner violence statistics. Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse. Retrieved from http://www.adfvc.unsw.edu.au/PDF%20files/Fast_Facts_1.pdf

De Goede, M. (1996). Ideology in the US welfare debate: Neo-Liberal representations of poverty. Discourse & Society, 7 (3), 317-357. doi: 10.1177/0957926596007003003.

Department of Human Services (2013). The Coalition’s policy for paid parental leave. Retrieved from http://lpaweb-static.s3.amazonaws.com/The%20Coalition%E2%80%99s%20Policy%20for%20Paid%20Parental%20Leave.pdf

Doughty, N. (2014, January, 16). The forgotten violence victims. Alt Media. Retrieved from www.altmedia.com.au

Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. London: Edward Arnold.

Finnemann, N. O. (2011). Mediatization theory and digital media. Communications, 36, 67-89. doi: 10.1515/COMM.2011.004.

Fogarty, D. (2013, January 1). Changes will encourage work: Macklin. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved from the ProQuest Australia & New Zealand Newsstand.

Fraser. N. & Bourdieu, P. (2007). (Mis)recognition, social inequality and social justice. London: Routledge.

Gordon, W. T. (2010). McLuhan: A guide for the perplexed. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Griffin, E. (2000). A first look at communication theory (4th ed.). Boston: McGraw Hill.

Grimshaw, T. (Presenter). (2012, May 23). A Current Affair [Television broadcast]. Sydney, Australia: Nine Network.

Grimshaw, T. (Presenter). (2012, August 16). A Current Affair [Television broadcast]. Sydney, Australia: Nine Network.

Grimshaw, T. (Presenter). (2012, December 19). A Current Affair [Television broadcast]. Sydney, Australia: Nine Network.

Hamilton, M. (2012). The ‘new social contract’ and the individualisation of risk in policy. Journal of Risk Research, 17 (4), 453-467. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2012.726250.

Harr, M. (2013, May 7). Abbott: ‘Paid parental scheme for women of calibre’. News.com.au. Retrieved from http://www.news.com.au/finance/work/big-business-slams-abbotts-paid-parental-leave-scheme/story-e6frfm9r-1226636500339

Harvard University (2008). Thematic analysis. Retrieved from http://isites.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=qualitative&pageid=icb.page340897

Hockey, J. (2014, May 13). Budget speech 2014-2015. Retrieved from http://www.joehockey.com/media/speeches/details.aspx?s=129

Huber, E. & Stephens, J. D. (2001). Development and crisis of the welfare state: Parties and policies in global markets. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Huda, P. R. (2001). Singled out: a critique of the representation of single motherhood in welfare discourse. William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law, 7 (2), 341-381.

Hutchens, G. (2014, September 10). Abbott budget to leave poorer women worse off. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/abbott-budget-to-leave-poorer-women-worse-off-20140910-10f4dw.html

Kelly, M. (2010). Regulating the reproduction and mothering of poor women: the controlling image of the welfare mother in television news coverage of welfare reform. Journal of Poverty, 14, 76-96.

Lacey, N. (2009). Image and representation: Key concepts in media studies (2nd ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lens, V. (2002). Welfare reform, personal narratives and the media: how welfare recipients and journalists frame the welfare debate. Journal of Poverty, 6 (2), 1-20.

Marks, D. F. & Yardley, L. (2004). Thematic and content analysis. In D. F. Marks & L. Yardley (Eds.), Research methods for health and clinical psychology (pp. 56-69). London: Sage Publications.

Martin, L. (2012, October 8). Welfare cuts worry Labor backbenchers. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/un-urged-to-help-single-parents/story-e6freuz0-1226490499436.

Mestan, K. (2014). Paternalism in Australian welfare policy. Australian Journal of Social Sciences, 49 (1), 3-22.

Misra, J. & Moller, S. & Karides, M. (2003). Envisioning dependency: Changing media depictions of welfare in the 20th century. Social Problems, 50 (4), 482-504.

Morris, J. (Ed.) (1992). Alone together: Voices of single mothers. London: The Women’s Press Limited.

Pascoe, C. M. (2006). Chapter 2 literature review: Theories of motherhood and mothering in film. Retrieved from http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/385/7/adt-NU1999.0010chapter2.pdf

Porter, A. (2014, January 7). The real danger in Cory Bernardi’s comments. The Drum. Retrieved from www.abc.net.au

Ross, K. & Nightingale, V. (2008). Media and audiences (2nd ed.). Berkshire, England: Open University Press.

Rothman, B. K. (2000). Recreating motherhood (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Schram, S. F., Soss, J., Houser, L. & Fording, R. C. (2010). The third level of US welfare reform governmentality under neoliberal paternalism. Citizenship Studies, 14 (6), 739-754.

Schwartz, S. J., Luyckx, K. & Vignoles, V. L. (Eds.) (2011). Handbook of identity theory and research. New York: Springer.

Shaver, S. (2002). Australian welfare reform: From citizenship to supervision. Social Policy & Administration, 36 (4), 331-345.

Staley, L. (2008, January). Awkward problems in social policy. Institute of Public Affairs Review. Retrieved https://ipa.org.au/library/59-4_STALEY.pdf

Stevanovic, K. & Wilkinson, L. (Presenters). (2014, July 7). Today [Television broadcast]. Sydney, Australia: Nine Network.

Summers, A. (2002). Damned whores and God’s police. (2nd revised ed.) Camberwell: Penguin Books Australia.

Swain, S. (1995). Single mothers and their children: Disposal, punishment and survival in Australia. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Yosufzai, R. & Jones, L. (2013, January 2). Single mums bristle at Macklin gaffe. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/national/single-mums-bristle-at-macklin-gaffe/story-fncvk70o-1226546732751.

About the author

Emily Wolfinger recently submitted an Honours thesis to the University of Western Sydney, and this essay is based on her research. Emily is the co-author of several books including the generational tome, The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations.