‘Always Watching’: The Interface of Horror and Digital Cinema in Marble Hornets

Adam Daniel

Western Sydney University

Abstract

The YouTube ‘found footage’ horror series Marble Hornets, released intermittently between 2009 and 2014, provides a beneficial site from which to examine the shifting nature of spectatorship in the age of new media. This essay examines the post-cinematic experience of audio-visual horror, interrogating the status and cinematic capacities of the ‘third’ and ‘fourth’ screens of media theory (respectively, the computer and the smartphone or tablet). Much of horror scholarship has approached these types of images in terms of the representational aspects of the ‘monster’ contained therein, a process Marble Hornets frustrates through the inscrutable visual presence of its antagonist. Alternatively, this essay poses that works such as Marble Hornets deploy an aesthetic of distortion, both thematically and directly at the level of the audio-visual image. These destabilised sounds and images have particular sensory-affective and synaesthetic qualities, and thus power a unique bodily engagement with the works of found footage that utilise them. Marble Hornets uses its digital aesthetics and the structure of new media modalities to emphasise the powerful and unruly response of the body to the sensory excess of the image, and as such provides an alternative understanding to the manner in which we experience audio-visual horror narratives.

Introduction

In a darkened office I sit alone at my desk. Lit only by the wan flicker of the computer monitor I am searching for answers in the byzantine labyrinth that is the video library. Some are archival records of what happened, some are messages in response. With no way of identifying the authenticity of each video I am left to piece the puzzle together for myself.

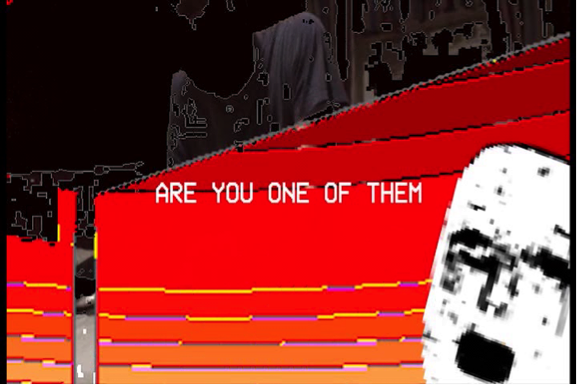

I press play on the next video, titled Conversion.

Unlike the previous entries that document the investigation, this one is a video response. A message. On screen, accompanied by a familiar electronic hum, the flicker of black and white bars reminds me of analogue static. In the noise, as though drifting to the surface, an anthropomorphic shape appears. Suddenly both are gone, replaced on screen with a code – one of many – among coloured geometric shapes. It reads: ENTRY # 000.129519. The numbers mean nothing to me, but tantalisingly hint that this is but one piece in a larger jigsaw puzzle.

The code too is soon replaced by a new image – an array of coloured digital vectors and a crudely animated spectral white face in the corner of the frame. The audio sounds like the whimper of a dying carnival, and a mutter of indistinguishable voices wash in and out like ocean waves. Behind the image appears the face of a familiar man, someone who is key to solving the puzzle, but equally inscrutable in his actions and behaviour. His voice has been muted. On screen, amidst the digital hiss of an image saturated with ruptures and static, a new message appears:

WHO ARE THE LIARS?

Despite knowing this query is directed to someone other than me, the question speaks to my own growing distrust of those behind the images, and the images themselves. On screen other recognisable figures appear, snatches from previous videos that have been compressed, garbled, digitally disfigured.

The video asks: ARE YOU ONE OF THEM? And then threatens: REMEMBER TO LOOK BEHIND YOU.

A spectral body of static recedes into the darkness on screen. The soundtrack becomes a sonorous growl that shifts in pitch as the image continues to break down. The growl recedes, replaced by a deep hum as more indecipherable batches of numbers flash on to the screen. While my mind struggles to solve the puzzle, my body is already offering its own inchoate answer to the question posed by the unnerving sounds and images.

The video finishes. YouTube cues the next link: Entry #75. Sitting in the dark I consider, just for a moment, looking behind me – but I remain still, body taut, nerves jangling, eyes riveted to the screen as the next video begins to play.

§

The experiential description of watching the video ‘Conversion’ described above provides a tantalising glimpse into both the content and effect of the 131 YouTube videos that comprise the web horror series Marble Hornets. Made by a core group of three amateur filmmakers, the Marble Hornets videos were sporadically uploaded to a YouTube account of the same name between 2009 and 2014. The series engages with the now-familiar trope of ‘found footage horror’ in that it claims to be the product of twenty-something Jay’s investigation into his filmmaker friend Alex Kralie’s discarded tapes – an unfinished student film project named ‘Marble Hornets’. When Alex suddenly and inexplicably ceases working on the project, Jay persuades Alex to let him to have the tapes under the proviso that Jay never mentions them to him again. Subsequently, Alex mysteriously transfers schools and loses contact with Jay. The main gambit of the series is that each video uploaded is a discovery from Jay’s exploration of the archive that may shed light on Alex’s disappearance. Gradually it becomes clear that Alex’s filmmaking endeavour is ‘haunted’ by a possibly malevolent entity – an unnaturally tall, thin faceless man in a black suit, who is only ever referred to as ‘The Operator’.

Those familiar with horror figures will identify him as a version of ‘the Slender Man’, a relatively new mythological figure created by artist Eric Knudsen in 2009. The Slender Man mythology found life in internet forums but soon took on a life of its own, spreading to short stories, films, and video games. Within Marble Hornets, this enigmatic and frightening figure, in the form of The Operator, first appears only in glimpses but soon begins to have definite and damaging effects on all of those involved in the film.

Figure 1. The Slender Man. n.d.

Figure 2. The Operator #1. (DeLage & Wagner, 2012).

As the Marble Hornets videos were slowly released to YouTube, the creators added an innovative twist to the storytelling in the form of response videos posted from an enigmatic and unknown second ‘narrator’ called ‘ToTheArk’. These occasional reply videos were less interested in unveiling the mystery than in fostering questions that required compulsive further investigation: ‘Conversion’, described above, is a quintessential example. Composed mainly of elaborate visual codes and puzzles, they are the most viscerally affective and at times, the most terrifying aspect of the series.

It comes as no surprise then that ‘ToTheArk’ becomes entwined with the central narrative as not only a commenter but as someone prompting the central characters. For a follower of the series, the interplay between the two sets of videos, and the resulting immersive engagement for those who sought to solve the puzzle, offer a clear demonstration of how new media structures present exciting narrative potential for filmmakers. However, this is but one component of how Marble Hornets alters the dynamics of spectatorship. By turning to the genre of ‘found footage horror’ more broadly, we can also examine how this genre, and Marble Hornets in particular, offers a valuable location from which to explore the shifting nature of spectatorship in the age of new media. This essay will explore how the digital aesthetic and delivery modality of new media is generative of a unique bodily intensity, one that derives from a distinctive camera/body relation, the particular sensory-affective attributes of destabilised sounds and images, and the synaesthetic and haptic qualities that accompany them.

Found footage horror and new media

As Cosimo Urbano notes in an essay on the merits of psychoanalytic approaches to various forms of horror, ‘found footage’ is a term that refers to:

… the conceit that the movie was filmed not by a traditional, omniscient director, but by a character that exists within the film’s world – and whose footage was discovered sometime after the events of the film’ (2004, p. 25).

The most common trope is that the film was compiled after the events portrayed on screen using recovered tapes and film. It can be composed of footage from diegetic cameras operated by the characters, or from surveillance footage in the diegetic world of the film or, more recently, from recordings of computer screens. A loose definition would also allow for the “mockumentary” components of films such as The Last Broadcast and The Last Exorcism, in which the film is presented as a documentary, complete with interviews, voice-overs and other documentary techniques.

Situated in the intersection between digital cinema aesthetics, new media and horror, Marble Hornets opens up valuable questions regarding the post-cinematic experience of spectatorship, particularly regarding the status and cinematic capacities of the ‘third’ and ‘fourth’ screens of media theory, the computer and the smartphone or tablet (positioned historically after the ‘first’ and ‘second’ screens of the cinema and television). In order to examine these questions most effectively, however, it is crucial to consider them through the frame of the horror genre’s inextricable connection to the body of the viewer. This indissoluble link between bodily affect and horror is contained in the word’s etymological origins: horror is derived from the Latin horrere, which means to shudder or bristle. The affective qualities of the experience of horror in its various forms literally touch the spectator in a corporeal manner: horripilation (also known as goosebumps) bristles our skin, our nerves involuntarily flinch, our heart races, our viscera contracts. And yet much of horror film scholarship has, until recently, been driven by an ocularcentric logic that sees audience immersion principally occurring via perceptual and cognitive engagement with the representational elements that drive narrative-based cinema: these bodily responses are codified as purely psychological reflexes to the semantic content of the image.

The contemporary focus has shifted to an equal consideration of the affective and sensorial power of cinema on the body. In The Horror Sensorium, for example, Angela Ndalianis (2012) considers the full range of both sensory and intellectual encounters with horror, and puts specific emphasis on how horror fiction ‘translates (its) sensorial enactments across our bodies’ (p. 3).

In considering how the various modalities of new media have interfaced with the genre of horror, it is crucial to acknowledge this link between sensorium and corporeality. The specificities of these novel forms generates a particular intensification of bodily affect, one that amplifies that which is produced by the conventional horror film. This understanding is derived from a body of work on embodied spectatorship that has systematically argued for the impossibility of a distinction between body and mind. Vivian Sobchack, a leading theorist in the field, argues instead that:

… we see and comprehend and feel films with our entire bodily being, informed by the full history and carnal knowledge of our acculturated sensorium.” Her work is akin to much of the scholarship in this field in that it responds to the extent to which contemporary film theory has struggled with the comprehension of human bodies being “touched” or “moved”, not only in the figurative sense, but also in the literal sense (2004, p. 63).1

This shift in focus towards examining the sensory-affective properties of digital cinema and new media in relation to horror is vital given much of the early scholarship on horror has focused on the monster and what it represents. These distinct and disparate conceptions include but are not limited, to the application of aspects of psychoanalytic theory to the monster’s role as allegory, its position as a reflection of societal trauma post-9/11, and its role within a holistic social and cultural context. Each field presents its own argument for the spectatorial affect of horror. Theories based on psychoanalytic foundations, for example, extend Freudian or Lacanian theories of how the unconscious structures representation wherein the monster serves a particular role in re-establishing a symbolic order. Allegorical interpretations, on the other hand, attempt to place the monster within a defined social and historical context, wherein the monster becomes representative of a threat to recognised social or cultural mandates.

In The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart, one of Noël Carroll’s fundamental theses is that horror centrally requires the presence of two evaluative components by audiences in their contemplation of its central monster: that the monster is regarded as both threatening and impure. He contends that, if either element is missing, the effect will be incomplete – a monster without impurity generates only fear, whereas a monster without threat produces only disgust (1990, p. 28). Building upon Mary Douglas’ classic study, Purity and Danger, Carroll infers that the impurity present in horror emerges from what Douglas defined as ‘the transgression or violation of schemes of cultural categorisation’ (1990, p. 31). That is to say, in Carroll’s terms, horror as a genre relies on beings, creatures or elements that are categorically contradictory, incomplete or formless. Carroll further argues that the presence of these monsters is the intellectual hook that draws the spectator in. Horror narrative works, he writes, ‘because it has at the center of it something which is given as in principle unknowable’ (italics his) (1990, p. 182). He presents the creation and consumption of horror fiction as the intellectual desire for the process of discovery, revelation and ratiocination of the ‘putatively unknowable’ (1990, p. 184).

What many of these scholarly considerations do not fully account for is the corporeal primacy of horror film. Certainly, if we were to ground an analysis of horror’s capacities in the aforementioned disciplines of thought, we would find many salient observations – the cognitive pleasure in horror film Carroll advocates is not irrelevant. However, when the appeal of horror film is constrained to the potentialities of a sharply defined central monster or a narrative drive to know the unknowable, it neglects to consider that horror cinema engages with us at a level that goes beyond cognitive evaluation of potential threat and impurity. Likewise, considerations that latch on to submerged psychoanalytic compulsions at its origins, or the veiled social currents that shape its allegorical role, are each too limited to be solely that which propels the horror genre’s power and appeal.

Found footage horror as a genre presents a fertile field to examine alternative considerations that advocate a broader conception of horror’s particular capacities beyond the centrality of a cognitive consideration of the monster. The modern trend of found footage horror film was arguably launched by the success of The Blair Witch Project in 1999. In Found Footage Horror Films (2014), Alexandra Heller-Nicholas offers perhaps the most comprehensive study of the sub-genre’s origins and effects. One of the central questions of her analysis focuses on the inherent instability of the construction of verisimilitude in found footage. That is to say, although the content that the cameras are capturing and recording is thought to be impossible (supernatural entities such as ghosts, Bigfoot, aliens, among others), the documentary-style record encourages belief. Heller-Nicholas overcomes this dichotomy with the concept of a spectator engaging in ‘active horror fantasy’ (2014, p. 8).

This conception of the experience of horror film, like many of those listed above, requires the active decision of the viewer to assert a form of cognitive control over their experience. I would contend that this offers only a partial understanding of the experience of horror, and that projects such as Marble Hornets are also able to traverse this fantasy through their sensory-affective excess. That is to say, the process Heller-Nicholas advocates cannot account for the intensification of experience for many of those who disavow the verisimilitude of found footage horror, but the amplification of the spectator’s sensorial engagement offers an alternative explanation.

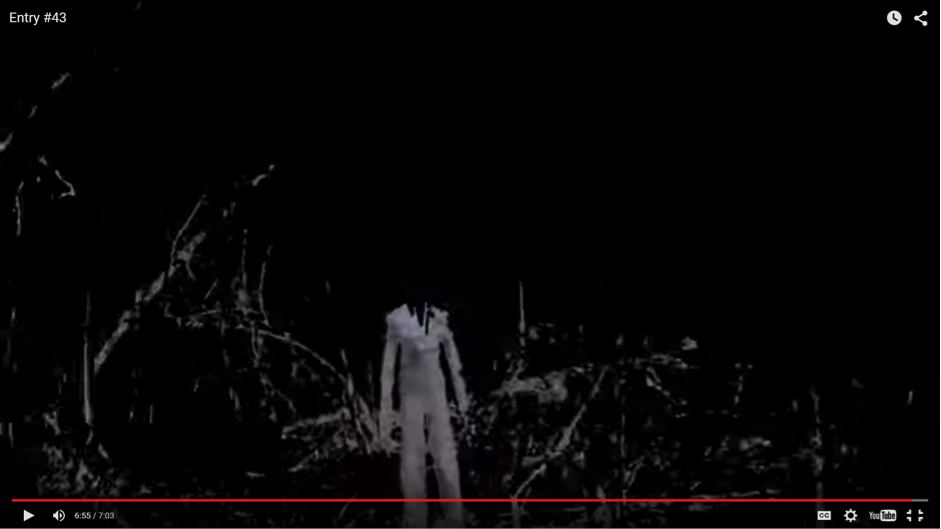

Like many found footage horror subjects, the ‘monster’ of Marble Hornets –the aforementioned The Operator – is captured only in tantalising glimpses. It appears to have no ability to communicate, outside of the interference it causes to video and audio recordings, and its motivations are largely inscrutable. Its appearance and influence does seem to generate a nondescript sickness, and an aggression in those who are exposed to it, but its malevolence is largely contained. When it does appear, it is often out of focus, obscured behind visual layers, or at the edges of frame, such as in the following examples.

Figure 3. The Operator #2. (DeLage & Wagner, 2012).

Figure 4. The Operator #3. (DeLage & Wagner, 2012).

Figure 5. The Operator #4. (DeLage & Wagner, 2014).

While this impenetrability does fit with Carroll’s contention that horror proceeds from our pursuit of the ‘unknowable’, it does not explain the deeply felt bodily intensity of experience in the moments that border The Operator’s appearance, and in response to the ToTheArk videos. This raises the potential that the source of horror in these films resides not primarily in The Operator’s presence, but in the combination of the digital aesthetic and the delivery modality of the computer screen or smart phone. This consideration reframes horror as a sensory-affective experience that actively questions the hierarchy of perception and cognition, in that it is no longer the conventional progression of cinematic narrative that is most important, but the embodied manner in which we first experience the image. Through the process of implicating the body of the spectator in a palpable way, cinematic new media such as Marble Hornets may have effects that overpower this drive to cognitive rationale.

New media artefacts and embodied experience

This is especially true of new media artefacts that are primarily experienced via smartphone or computer screens, which is where most consumers of Marble Hornets engage with the series. While each of these mediums generates its own particular relations of embodied experience, there are similarities between the two. Ingrid Richardson (2010) draws attention to the way these screens produce distinct differences from traditional televisual and cinematic screens in terms of ‘proximity, orientation and mobility’. She contends that these screens draw us into the image, arguing ‘we are no longer “lean-back” spectators or observers but “lean-forward” users.’ Our interaction with these images involves physical engagement, whether it be through the tactile manipulation of the smart phone screen or the instrumental use of the mouse or keyboard of the computer. As such, it produces a unique type of engagement. That is not say that an embodied experience of the cinematic image requires spectatorial movement, but that in their requisite physical engagement new media forms produce an altered body-tool relation which has effects on the corporeal schematic that usually dominates the experience of cinema.

This modified techno-perceptual dynamic is intimately connected to the ubiquitous interaction with screens and cameras that is an inescapable element of contemporary life. One glance at any crowded urban space and it is self-evident with hundreds of people engaged in the act of either viewing or recording. Found footage horror, particularly those films viewed on the smartphone or computer screen, capitalises on and distorts this relationship through its presentation of horrific imagery on machines which we are familiar with as recording devices. This infection of the machine can be explicitly horrific, such as the undead of films like [REC], or, in the case of Marble Hornets, a rupture of the image itself, which potentially surpasses the power of the unambiguous presence of overtly horrifying imagery. It is this creation of a liminal space for a spectator, in which their conceptions of cinematic reality and unreality are unmoored by the complex relations we have with screens and cameras, that aids in the production of an experience that denies the kind of spectatorial disbelief that is more easily summoned in standard horror genre films.2 As Kimberly Jackson (2013) states in Technology, Monstrosity, and Reproduction in Twenty-First Century Horror, by focusing on how inextricably linked we are to our technologies, these kinds of films introduce a hyperawareness of ‘the undecidable relation between reality and image.’ She contends that this irresolution ‘becomes horrific and affective rather than desensitizing and anaesthetic’ (p. 35).

It is unsurprising that the consequences of this large scale shift to the pervasive tethering of humans and cameras/screens has filtered into cultural products like television and cinema, and vice versa. Joel Black (2002) contends that cinema itself holds much of the burden of responsibility for the compulsion people feel to render every element of their daily lives as a visible spectacle. Catherine Zimmer identifies the genre of found footage as the best representation of:

the increasing ubiquity of visual recording technologies in the hands of the “average” person and the drive to record, on such consumer level technologies, virtually everything: to document, represent, share and spectacularize the world as it unfolds before each individual (2015, p. 77).

The history of horror film demonstrates that large-scale technological shifts inevitably warrant investigation within the genre; as Jeffrey Sconce observes in Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television:

Tales of paranormal media are important … not as timeless expressions of some underlying electronic superstition, but as a permeable language in which to express a culture’s changing social relationship to a historical sequence of technologies (2002, p. 53).

As these technologies perform as extensions of human consciousness and perception, they are also imbued with ghostly traces of the information that passes through them. The residue of this information is a haunting of sorts and to see the effects of this haunting one need only examine how quickly the ‘new’ media of their times – photography, radio, the telegraph and the telephone – were soon imbricated with the paranormal. The internet, particularly YouTube, is the most recent technology to retain this spectral stain, and Marble Hornets capitalises on this in a manner that conventional cinematic found footage cannot. It does so in three specific ways – by exploiting the particular kinaesthetic qualities that advances in digital camera technology allow, by manipulating the digital image to increase its sensorial properties, and by employing the hypertextual, non-hierarchical nature of new media to alter the spectator’s experience of duration and proximity.

The spectatorial body and the camera of Marble Hornets

Marble Hornets, like all found footage, exists only through the pervasive presence of cameras within the diegetic world. Excluding the ToTheArk video responses mentioned earlier, everything we see throughout the series is captured by a camera either carried or mounted to the body of one of the protagonists. One of the biggest innovations of digital cinema is the mobility and economy of camera size, and economy of camera price, which allows for an entirely new world of images. Horror is one genre where filmmakers actively experiment with this new flexibility in order to best intensify the spectatorial experience. In Marble Hornets, as paranoia grips the protagonists, they take to recording everything, even going so far as wearing body-mounted cameras. While the use of handheld cameras is not particularly innovative in and of itself given its origins in the Direct Cinema movement of the late 1950s, the manner in which Marble Hornets engages with its particular rhythms and movement has different effects. ‘Found footage’ as a genre has often played with loss of focus, incongruent framing, and camera shake in an effort to conjure verisimilitude with the documentary mode. The particular cadence of movement produced by the bodily-attached camera in Marble Hornets has different effects while promoting this same realism. It heightens the sensory engagement of the viewer – not just of vision but of the kinaesthetic qualities that vision is associated with – to the point where the body and its position in the world feels disrupted. Horror theorist Anna Powell (2006) identifies this increase in sensory participation as the result of pre-cognitive affects on our mechanisms of perception, arguing that horror’s ‘undermining of normative perspective’ intensifies participation at the sensory level (p. 5).

To clarify, this is not a visual identification with the camera as identical to the spectator’s eye, but instead the ability of the sound and image to engage all the senses and stimulate our entire corporeal presence through the particularities of camera movement through environment. In fact, I would argue that the bodily mounted cameras stymie the visual identification with the eye and produce a whole new experience of camera as body. In Entry #83, for example, the character Tim is racked with coughing fits that harken the presence of The Operator. His inability to stand and his struggles to breathe are visually reproduced in an unconventional manner: by a camera with a fish-eye lens that captures the world from the position of the sternum. In this way, the camera synchronises more fully with the body of the performer, a body that we become implicated with as we kinaesthetically synchronise with the movement of the image.

In The Address of the Eye Vivian Sobchack (1992) offers perhaps the most comprehensive theorisation for how this synchronisation occurs, positing a reciprocal relationship between the viewer body and a filmic ‘body’. Sobchack examines how the tools of cinema, camera and projector, are intricately connected to the perception of filmmaker and spectator through an analysis of philosopher Don Ihde’s embodiment relations. Drawing on Merleau-Ponty, Ihde (1990) uses the term ‘embodiment relations’ to label the imbrication of tools into our corporeality, wherein the artefacts of the world become part of our bodily experience. In an embodiment relation, Ihde argues, ‘I take the technologies into my experiencing in a particular way by way of perceiving through such technologies and through the reflexive transformation of my perceptual and body sense’ (1990, p. 72). This leads to a symbiosis between user and artefact through action. The focus of Ihde’s contemplation is primarily the intentional connection between perception and its object in the use of scientific instruments like the microscope or telescope. Sobchack, applying Ihde’s philosophical investigation to cinema, notes a distinct conceptual difference when she writes:

The single technological relations of individual embodied persons to instruments that Ihde describes are necessary but not sufficient to the film experience. They are imbricated in, but cannot, in themselves or in their sum, account for the doubled and inclusive machine-mediation of the film experience, an experience that results in the constitution of a reversibly perceptive and expressive text and in intersubjective communication (1992, p. 191).

Sobchack further extrapolates the dynamics of relations between spectator-world-filmmaker as produced through the tools of camera and projector in a manner that exceeds the scope of this paper. What is of value from this work in relation to Marble Hornets, however, is a consideration of the manner in which our existing embodiment relations with smartphones contribute to a dynamic bodily synchronisation with the image, particularly when the series is viewed on a smartphone screen. I contend that this occurs primarily due to the fact we are using our recording tools as viewing tools, and that a bleed-through in our existing relationships with these technologies to the image occurs. Sobchack touches upon this, although the ‘technology’ she refers to is camera and projector, when she writes:

Insofar as it concerns the technology of the cinema, this embodiment relation between perceiver and machine genuinely extends the intentionality of both filmmaker and spectator into the respective worlds that provide each with objects of perception. It is this extension of the incarnate intentionality of the person that results in a sense of realism in the cinema…. What is experience as the sense of realism in the phenomenon is genuinely lived as the experience of a real or existential act of perception (1992, p. 181).

This sense of realism is no doubt heightened when the tool used to view the image shares many of the same qualities as a recording device as the tool used to capture the image. Sobchack goes on to refer to the camera’s potential for ‘amplification of perceptual experience’, identifying its potential for a perception of the world that is ‘unavailable to human vision’, yet one that we still experience similarly to our direct lived-body engagement with phenomena (1992, p.183). It is this amplification of movement that Marble Hornets employs through its bodily-mounted cameras – although most spectators experience the series in relative quietude, there is a particular quality to the movement that transfers as a kinaesthetic ‘sense’. When this occurs, we move, fall, crouch, hide, run, and struggle to breathe, all without ever leaving our seats. Sobchack refers to this as the spectator’s body ‘kinetically “listening” to the movement of another’, ‘another’ here referring to the filmic body (1992, p. 186).

Jennifer Barker (2009) in The Tactile Eye offers us another way to appreciate the manner in which film images translate to the spectatorial body. Using ‘gesture’ as term to codify expressive bodily movement that is directed towards the world, she argues that films also contain gestures in the form of cinematic devices or techniques (2009, p. 78). Employing Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining as an example, she argues that the:

… repeated, slow moving surreptitious camera movement… demands a reply of some kind from the attentive spectator’s body. It evokes a corresponding but not predetermined gesture from our bodies” (2009, p. 78).

In a similar manner, Marble Hornets has its own set of repeated gestures in relation to camera movement: in the early episodes, the handheld camera and its ability to zoom becomes like a searching eye, seeking clues or details in the image. In the latter episodes the body mounted camera and its particular rhythms becomes a particular type of passage through the world: apprehensive, paranoid, ever vigilant.

However it is not only the particular type of movement exemplified by the cameras of Marble Hornets that produces a specific bodily intensity for the viewer – it is also the qualities of the image itself. The particular sensory-affective attributes of digital cinema present the horror genre with a playground of methods to heighten intensity, especially in regards to digital manipulation of the image. Marble Hornets illustrates this in two ways: firstly, through the digital ruptures caused by the presence of The Operator, and secondly, through the form of the ToTheArk videos, which threaten the viewer through their destabilisation of sound and image.

Deleuzian film theory presents a natural ally with this conception in the manner in which Deleuze contends that certain filmic images destabilise or frustrate the conventional links that hold action and situation together. In Cinema 2, Deleuze contends that a rupture and imagistic shift arose in many of the films post-World War II, a shift that he identifies as emerging from a crisis in the action-image. The unfettered freedom that cinema had seemed to promise in its inception had devolved into the rigidity of cliché and repetition. Ronald Bogue identifies these clichés in the manner in which Hollywood created:

… an integrated system of practices… that ensures a seamless and continuous presentation of action within a single time and space. A commonsense, rational sensori-motor schema informs the Hollywood system (2003, p.109).

Marble Hornets, as an outlier to the Hollywood system in its independent production and release, is more freely able to transgress the limits of this ‘rational’ system in favour of images and sounds that are counter or excessive to a ‘seamless’ presentation. As such it shares qualities with what Deleuze identifies as a mutation that occurred in neo-realist cinema that challenges the chain of situations and actions that continually create the same types of images: a mutation he labeled the ‘time-image’. The cinema of the ‘time-image’ is more productive of ‘opsigns’ and ‘sonsigns’: pure optical and audio images that facilitate the potential collapse of the sensory-motor process, in that they interrupt the coherent flow from situation to action or action to situation (1989, p. 6).

Certainly the form of cinema has continually transformed since Deleuze proposed the ‘time-image’ as a response to neo-realism and the French new wave, and it is not my contention to equate the form of digital cinema with the ‘time-image’ in any wholesale way. However, Deleuze’s description of the new sensory-motor schema presented by the post-war art cinema does have relevance to Marble Hornets in that the characters of Deleuze’s time-image cinema are, like those of Marble Hornets, often trapped in a disjointed or opaque world where their perceptions and actions are no longer in synchronisation. For Deleuze, it is ‘the purely optical and sound situation which takes the place of the faltering sensory-motor situations’ (1989, p. 3) in this kind of cinema a statement that could also be attributed to the irruption of the ToTheArk videos.

Deleuze proposes that in the cinema of the ‘time-image’, traditional notions of identification with a character can be inverted, so that the character themselves becomes a kind of viewer of the diegetic world he inhabits. He describes the situation of this character as such:

He shifts, runs and becomes animated in vain, the situation he is in outstrips his motor capacities on all sides, and makes him see and hear what is no longer subject to the rules of a response or an action. He records rather than reacts. He is prey to a vision, pursued by it or pursuing it, rather than engaged in action (1989, p. 3).

This is an apposite description of the constantly recording protagonists of Marble Hornets, and provides another way for us to understand the unconventional duration of some its images, and the manner in which this duration is all too often disturbed by dissonant sound and image. Anna Powell (2006) in Deleuze and Horror finds in the genre of horror a natural state for these dissonant experiences of image and sound. The affect of horror, for Powell, can originate in the incongruous colours, distorted sounds and hallucinatory images of the genre. Each of these contributes to an experience of spectatorship as a Deleuzian assemblage between viewer and text, an assemblage that is, in Deleuzian terms, molecular and corporeal. What this allows for is an experience that can transcend the normative, static structure of what Deleuze classified the ‘molar plane’ – the register of film that, in Elena Del Rio’s conception (2008), is analogous to traditional narrative, as opposed to the ‘molecular plane’, home to the affective-performative register of cinema.

The ‘molar plane’ of horror films would correspond to the reified structures of conventional narrative that would promote the film’s purpose as a logical progression of cause and effect leading to a satisfactory narrative conclusion. In brief sketch, the presence of the monster would destabilise the environment of the main characters, but this disruption would be stabilised by the struggle against and eventual destruction of the monster. Each scene would perform a vital role in the narrative chain that leads to this conclusion. Marble Hornets subverts these conventions through its repeated presentation of actions and situations that frustrate the sensory-motor schema of conventional narrative, in favour of the disjointed and uncoordinated (in)actions and situations of the time-image.

It also does so by the presence of its visual and audio ruptures, and through the unique form and chronology of the ToTheArk videos. Throughout the series, the vast majority of the videos recorded by Alex Kralie for his student project, and later, the videos of Jay and Tim’s investigations, contain the trace of some form of digital decay, be it static, loss of tracking, desaturation or hyper-saturation of colour, loss of audio or distortion of audio, or digital bleed-through of the image.

The cause of this, within the world of the story, is the presence of The Operator whose manifestation appears to degrade or warp recording devices. As a result, pivotal moments of narrative revelation are often lost or obscured by the degradation of the digital record. Capturing a clear image of The Operator on camera appears impossible and direct confrontations between the characters and The Operator, such as in Entry #43, when Alex approaches it in the woods, are lost in a fog of image decay as the image polarises and fades away.

Figure 6. Entry #43 (DeLage & Wagner, 2011).

Dialogue is also lost in a similar manner, drowned out by bursts of discordant noise or unexplainably muted. In Entry #83 these tears in the image and audio become literal tears in space and time, as The Operator’s presence appears to produce a temporal and spatial warp that envelops the fleeing Tim.

The aesthetics of distortion: synaesthetic qualities of sound and image

What these digital ruptures also produce, outside of the frustration of narrative progression or resolution, is an intensification of our bodily engagement through synaesthetic means. In The Hidden Sense, Crétien van Campen defines synaesthesia as ‘a neurological phenomenon that occurs when a stimulus in one sense modality immediately evokes a sensation in another sense modality’ (2010, p.1). Applying this synaesthetic capacity to cinema, Laura Marks, in The Skin of the Film, claims that vision itself can be tactile, ‘as though one were touching a film with one’s eyes’ – she terms this process ‘haptic visuality’ (2000, p.xi). Marks draws her theoretical frame from art historian Alois Riegl’s interrogation of the hierarchy of perception.

This notion of haptic visuality is central to the claim that images of this kind can exceed the boundaries of Heller-Nicholas’ ‘active horror fantasy’, which includes a conscious or unconscious denial of the verisimilitude of the image. Vision, particularly in the horror film, involves an immersion in the filmic space: its atmosphere, its spatial relations, and its texture. Rather than processing a film purely on the level of sense-making through narrative and character, haptic visuality involves a new sensorial relationship that brings into play a synaesthetic exchange between light, colour, sound, mood and texture. This hapticity is not solely a link between image and body, but also extends to a kind of inhabitation of filmic geography for scholar Giuliana Bruno who labels this inter-subjective form of presence a ‘geopsychic architexture’ (2002, p. 4).

Entry 40 of Marble Hornets serves as a cogent example of this creation of space through images that stimulate our sense of tactility, creating a ‘geopsychic architexture’ of location that is immersive and potent for the viewer. The combination of Jay’s movement through the environment, the aural landscape of the various consistencies under the feet, the hyper-saturated colour and, towards the end of the video, the textural contrast between the organic and the manmade, allow the viewer to inhabit this location in a sensory way. These images are clear examples of Mark’s definition of haptic visuality where our interest is not so much in the textual elements of the image but in the textural. As Marks says, “Haptic looking tends to move over the surface of its object rather than to plunge into illusionistic depth, not to distinguish form so much as to discern texture” (2000, p. 162). She argues that these types of images draw on the viewer’s resources of memory and imagination, two capacities that are especially powerful in the realm of horror. The defining feature of haptic imagery is its reciprocal nature: Marks refers to the act of ‘denuding and dispossession’ that comes from the intimate meeting between viewer and work of art when there is no longer a clear delineation between the two.

Found footage horror films in particular use an aesthetic of distortion for thematic purposes, drawing on the way haptic imagery ‘puts the object into question, calling on the viewer to engage in its imaginative construction’ (Marks, cited in Barker, 2009, p. 62). This is most evident in the ToTheArk videos, where the filmmakers have intentionally ‘corrupted’ the images in order to produce the vividly textural and macabre imagery in the following examples.

Figure 7. Conversion (DeLage & Wagner, 2011).

Figure 8. The Operator #5 (DeLage & Wagner, 2014).

Figure 9. Not Enough (DeLage & Wagner, 2012).

The sensory engagement heightened by the visual ‘tears’ in the image, the auditory ‘tears’ that accompany them, and our synaesthetic responses to the imagery draw us into a new kind of relationship where our perceived control over our experience of the film through mastery of plot and narrative can be disrupted. By dislocating the image from its standard semantic role, we are also left with a disrupted relationship between the film and ourselves. As these videos reject the usual patterns of cause-and-effect motivated by narrative demands, they heighten our entanglement, and thus our tension and fear. This too is a movement away from ocularcentric logic where our understanding of the image is designed to be clear and unambiguous to a sensory logic that deemphasises the visual and accentuates the other senses in order to generate fear. When we replace the semantics of the image as our primary engagement with the series we are left with the idea of the image itself as enigma, puzzle, or code that does not necessarily require solving in order for it to be generative of an affective response for the spectator.

The auditory distortions mentioned above are not the only manner in which Marble Hornets capitalises on the audio-visual capacities of new media artefacts. A consideration of the interrelation of sound and image requires that we question any hierarchical arrangement between the two. Theorist Michel Chion, for example, rightly contends that ‘there is no soundtrack’ in that a film’s images cannot be studied independently of its sound, and vice versa (2009, p. xi). Instead, in relation to Marble Hornets, we can consider how sound is but one element of a heterogeneous unity. Chion goes so far as to insist that, with the embrace of polyphony, that is, multilayered audio tracks, ‘the visual image is just one more layer and not necessarily the primary one’ (2009, p. 119). He chooses the term ‘rendering’ to describe how, in the complex intertwining of all of the senses in the articulation of both film’s auditory and visual texture, sensations are conveyed that are truthful or effective regardless of their fidelity to an actual reproduction of the scene’s reality. For Chion, this explains how the interrelation of sound and image ‘can give us a vast array of luminous, spatial, thermal and tactile sensations that extend far beyond realist reproduction’ (2009. p. 241). This concept expands the synaesthetic foundations of ‘haptic visuality’ to integrate auditory components. Chion labels these as ‘trans-sensory perceptions’ – these are perceptions that ‘belong to no one particular sense but that may travel via one sensory channel or another without their content or their effect being limited to this one sense’ (2009, p. 496).

Distorted sounds, and particularly those that operate at either extremes of high or low frequencies, in combination with the image, are common to horror film, and activate a marked corporeal response. In Music and the Mind, Anthony Storr points out how sound may have even a greater capacity to elicit physical responses, in that it is far more difficult to dispel sound as easily as closed eyes can negate an image (1992, p.100-101). However, while the use of particular sounds or sound frequencies can produce the desired physiological response of shock, such as that of the ‘sting’ scare of conventional horror film, it cannot account for the nuanced multifaceted sensory response that videos such as ‘Decay’ produce – a low rumble underscores an undulating irruption of inorganic or mechanical noise that “renders” sensations of materiality, heaviness and potential danger in its combination with the image. Returning to Chion’s ‘trans-sensory perceptions’, this may be due to what he terms the essential trans-sensory dimension: rhythm, within which he includes audio texture and grain (2009, p. 496).

This is also evident when we look at the videos recorded by the participants: for example, ‘Entry #60’, where Jay investigates a tunnel under an original Marble Hornets filming location. The claustrophobic crawl space is lit only in glimpses by passing torch light, and it is the echo of Jay’s breathing and the clatter of his passage that constitute much of the sequence. This rhythmic combination is interrupted by Marble Hornets’ version of the ‘sting’ scare – the audio-visual distortion that signals the arrival of The Operator. However, prior to this, it is a fitting example of the particular auditory rhythms that are unique to this form of found footage, where diegetic sound is the predominant auditory accompaniment to the image. This auditory texture would, in conventional cinema, most often be added to with either score or effects that would further paint in the ‘soundscape’. Viewed on either a computer or a phone screen, the unadorned verisimilitude of found footage is more fully accepted.

New modalities, new tensions

Any argument that advocates the equivalence of third and fourth screen media to cinema, has in the past been met with resistance and conjecture by many critics. Raymond Bellour, for example, contends that ‘neither television nor computers, not the Internet, mobile phones or a giant personal screen can take the place of cinema’ (2012. p. 211). In the realm of horror scholarship, Julian Hanich (2011) argues that the theatrical experience is crucial in that it dialogically intertwines an individual’s immersion with the collective experience, producing a pleasurable fear in the meeting point of individuality and collectivity. What is important to acknowledge is that these experiences do not replace cinema, but instead utilise the respective technologies of the computer and the smartphone to create a unique experience of spectatorship that shares characteristics with the traditional horror spectatorship, but that has capacities that cannot be taken advantage of by the conventional theatrical experience.

The form of the internet video archive and its potential for user interaction is one particular capacity that has been skilfully utilised by the Marble Hornets creators. Smartphones and computers, while perhaps limited in terms of being experienced as a spatial collective, open up new methods of communal media experience through online social interactivity. The genetic elements of Marble Hornets were formed in the online community of the Something Awful website, and the interactivity and formation of community of that site carried over in the DNA of the initial Marble Hornets video posts, which led to the creation of new networks in order to speculate on both the meaning and the authenticity of the videos.

The videos themselves also promote greater individual immersion through the spectator’s control over duration, proximity, and chronology. With its intentionally fractured chronology, Marble Hornets is an apposite example of this interactive potential for re-mix and the concomitant increase in spectatorial immersion. The Marble Hornets wiki promotes several playlists of the series, including ‘release order’, ‘a tentative chronology’, and ‘suggested order’ (which places the response videos in context). Each variation of the series produces not only new understandings of the narrative content, but in the dynamics of its assemblage, a new affective resonance can form between the videos: for example, the infected imagery of a shadow passing a doorway in the entry Admission carries over into Entry #23, where every doorway in the dilapidated house seems to portend doom.

Duration and proximity are also altered through this modality. Sequences can be rewatched on loop, a compulsion that is inevitable when visual clues are hidden in the dense digital textures, and when the presence of The Operator threatens to infect every frame. The many online communities that were drawn into the mystery, much like the characters, encouraged avid viewers of the series to capture and parse still frames, searching for answers. Watching the videos on smartphone or computer screen offers the spectator the opportunity to literally ‘lean in’ to the image, a compulsion that arises for many viewers in the temporal elongation of scenes of dread (the flipside of this lean-in is the discomfort experienced by those for whom the palpability of dread is too extreme, which results in aversion). The opening prologue of this article is intended as a vivid example of how and why this compulsion to lean in is generated as much by the video’s sensory aspects as its narrative content.

What each of these observations regarding Marble Hornets’ distinctive properties draws attention to is that, in relation to corporeal engagement, form is equally as crucial as content. In his article ‘Delirious Enchantment’, Adrian Martin speaks to the categorical distinction of representational and non-representational elements in film as false and misleading. Instead, he positions our spectatorial engagement with ‘colour, texture, movement, rhythm, melody [and] camera work’ as equally important as setting, story, dialogue and plot. He writes:

There is another register of feeling in our contact with the arts (and especially film). It is the moment when, in the imaginary experience of viewing, hearing and being absorbed in something that is unfolding, we pass out of ourselves, just a precious little bit for a precious little while. We become rivers, pylons, doors, tin cans. And we join, also, with the flux of the non-representational: the colours, shapes and edits, those gestures of the film itself as a living, breathing, pulsating organism (2000, p.125).

This ‘living, breathing, pulsating organism’ can sometimes be horrific. It can destabilise our comfortable distance from the image and bring us closer than we want to be. It can both fascinate and repulse us, and it can affect us in viscerally intense ways: in our muscular response, our breathing, at the level of our skin. Heller-Nicholas (2014) draws attention to the power of Marble Hornets residing in its ‘mistrust of language – paralysed by paranoia, its protagonists are notoriously incapable of discussing even with each other the terrifying supernatural forces that plague them.’

This recourse to something other than language to understand the events of the series is echoed in the experience of the spectator. With only vague and unsettling hints at the origins of The Operator and its true connection to the myriad occurrences of the series, the viewer processes the images of Marble Hornets in a different way – at the level of the body, and its powerful and unruly response to the sensory excess of the series and the immersive properties of the modality through which it is delivered. Marble Hornets demonstrates how the combination of digital cinema aesthetics and new media structures of content can combine to accentuate the existing powers of the sub-genre of found footage horror. As a series, it pushes back against the homogenising forces of Hollywood horror filmmaking and illustrates the potential of cinema narrative that is unshackled from conventional structure. The modalities of the third and fourth screens offer fascinating potentials for genre filmmakers who wish to challenge these existing paradigms.

Footnotes

2 It is arguable, however, that this sub-genre has a limited shelf life, in that as its aesthetics are applied to satire or mockumentary its future impacts are potentially minimised.

References

Barker, J.M. (2009). The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bellour, R. (2012). The cinema spectator: a special memory, in Audiences: Defining and Researching Screen Entertainment Reception, ed. Ian Christie, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Black, J. (2002). The reality effect: film culture and the graphic imperative. New York: Routledge.

Bogue, R. (2003). Deleuze on Cinema. London: Routledge.

Bruno. G. (2002). Atlas of Emotion. London: Verso.

Campen, C. t. v. (2008). The hidden sense : synesthesia in art and science. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Carroll, N. l. (1990). The philosophy of horror, or, Paradoxes of the heart. New York: Routledge.

Chion, M. (2009). Film, a Sound Art. Chichester: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G. (1989). Cinema 2, the Time Image. Time Image. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press.

Elsaesser, T & Hagener, M. (2010). Film Theory: An Introduction through the Senses. New York: Routledge.

Hanich, J. (2010) Cinematic Emotion in Horror Films and Thrillers. New York: Routledge.

Hansen, M. (1993). ‘With Skin and Hair: Kracauer’s Theory of Film, Marseille 1940.’ Critical Inquiry 19, no.3. 437-469.

Heller-Nicholas, A. (2014). Found footage horror films : fear and the appearance of reality. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Heller-Nicholas, A. (2014). ‘Gothic Textures in Found Footage Horror Film.’ 7 December 2014. <http://www.gothic.stir.ac.uk/guestblog/gothic-textures-in-found-footage-horror-film/>

Ihde, D. (2002). Bodies in technology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ihde, D. (1990). Technology and the Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Jackson, K. (2013). Technology, monstrosity, and reproduction in twenty-first century horror. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Marks, L.U. (2000). The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment and the Senses. Durham: Duke University Press.

Martin, A. ‘Delirious Enchantment.’ Senses of Cinema 5 (April 2000). 9 May 2000. <http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/5/>.

Ndalianis, A. (2012). The horror sensorium: media and the senses. Jefferson: McFarland & Co.

Powell, A. (2006). Deleuze and horror film. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Richardson, I. (2010). Faces, interfaces, screens: Relational ontologies of framing, attention and distraction. Transformations, 18. Retrieved from http://www.transformationsjournal.org/journal/issue_18/article_05.shtml

Río, E. (2008). Deleuze and the Cinemas of Performance: Powers of Affection. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Rutherford, A. (2011). What Makes a Film Tick?: Cinematic Affect, Materiality and Mimetic Innervation. Bern: Peter Lang.

Sconce, J. (2000). Haunted media: electronic presence from telegraphy to television. Durham: Duke University Press.

Shaviro, S. (1993). The Cinematic Body. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Sobchack, V.C. (1992). The address of the eye: a phenomenology of film experience. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sobchack, V.C. (2004). "What My Fingers Knew." In Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Storr, A. (1992). Music and the Mind. New York: Maxwell Macmillan International.

Urbano, C. (2004). "What’s the matter with Melanie?": Reflections on the merits of psychoanalytic approaches to modern horror cinema. In S. J. Schneider (Ed.), Horror Film and Psychoanalysis: Freud’s Worst Nightmares. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, L. (1995). Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Zimmer, C. (2015). Surveillance cinema: New York : New York University Press.

Films referenced

Sanchez, E. & Myrick, D. (Directors). The Blair Witch Project [Motion picture]. USA: Haxan Films.

Avalos, S. & Weiler, L. (Directors). The Last Broadcast. [Motion picture]. USA: FFM Productions.

Stamm, D. (Director).The Last Exorcism. [Motion picture]. USA: Strike Entertainment.

Kubrick, S. (Director). The Shining. [Motion picture]. USA: FFM Productions.

Balagueró, J. & Plaza, P. (Directors). [REC]. [Motion picture]. Spain: Castelao Producciones.

Videos referenced

DeLage, A. & Wagner, T. (Directors). Entry #23. [Web video]. Available from: https://www.YouTube.com/watch?v=SzdZyZgCY58

DeLage, A. & Wagner, T. (Directors). Entry #43. [Web video]. Available from: https://www.YouTube.com/watch?v=zqQIVmauiXI

DeLage, A. & Wagner, T. (Directors). Entry #60. [Web video]. Available from: https://www.YouTube.com/watch?v=6a-pO2Pm37A

DeLage, A. & Wagner, T. (Directors). Entry #83. [Web video]. Available from: https://youtu.be/Tb33j_DWu8Y

DeLage, A. & Wagner, T. (Directors). Admission. [Web video]. Available from: https://www.YouTube.com/watch?v=rIe-a6-TNHI

DeLage, A. & Wagner, T. (Directors). Conversion. [Web video]. Available from: https://www.YouTube.com/watch?v=-xX7-eFWmy8

DeLage, A. & Wagner, T. (Directors). Decay. [Web video]. Available from: https://www.YouTube.com/watch?v=XhwO6wm76-U

Images referenced

Figure 1. The Slender Man. n.d. Retrieved from: http://media.vocativ.com/photos/2014/06/Slender-Man-History-032561603661.jpg

Figure 2. The Operator #1. (DeLage & Wagner, 2012). Retrieved from: https://www.YouTube.com/user/MarbleHornets/featured

Figure 3. The Operator #2. (DeLage & Wagner, 2012). Retrieved from: https://www.YouTube.com/user/MarbleHornets/featured

Figure 4. The Operator #3. (DeLage & Wagner, 2012). Retrieved from: https://www.YouTube.com/user/MarbleHornets/featured

Figure 5. The Operator #4. (DeLage & Wagner, 2014). Retrieved from: https://www.YouTube.com/user/MarbleHornets/featured

Figure 6. Entry #43. (DeLage & Wagner, 2011). Retrieved from: https://www.YouTube.com/user/MarbleHornets/featured

Figure 7. Conversion. (DeLage & Wagner, 2011). Retrieved from: https://www.YouTube.com/user/MarbleHornets/featured

Figure 8. The Operator #5. (DeLage & Wagner, 2014). Retrieved from: https://www.YouTube.com/user/MarbleHornets/featured

Figure 9. Not enough. (DeLage & Wagner, 2012). Retrieved from: https://www.YouTube.com/user/MarbleHornets/featured

About the author

Adam Daniel is a third year film studies PhD candidate at Western Sydney University. He is a member of the Writing and Society Research Centre. His thesis investigates the evolution of horror film, with a particular focus on the intersection of embodied spectatorship, neuroscience and Deleuzian philosophy.