Andrew Bolt and the discourse of ‘scepticism’ in the Australian climate change debate: A ‘distant reading’ approach using Leximancer

Myra Gurney

Western Sydney University

Abstract

In Australia since 2007, attempts to deal with anthropogenic climate change have become highly politicised, politically poisonous and discursively fractious. Central to the toxic politics has been a vocal media campaign from so-called ‘sceptics’ and ‘denialists’ who have largely framed their opposition to carbon reduction policies in terms of the scientific basis of climate change in general, and the economic implications, in particular. Using the text analytics program Leximancer, this paper applies a mixed methods approach of ‘distant’ and more traditional ‘close’ reading to examine a large sample corpus of the columns of prolific Australian conservative commentator and climate sceptic Andrew Bolt for the manner in which he discursively constructs his views on climate change. It then discusses the extent to which Bolt’s self-labeled ‘scepticism’ is consistent with both the traditional application of scientific scepticism and the broader strategies of climate change denialism and its role in legitimizing doubts about the both the veracity of climate science and scientific consensus. The Leximancer analysis works on a large scale corpus that demonstrates the manner in which Bolt’s arguments are inconsistent with genuine scientific scepticism, but are examples of denialism that is largely ideologically driven.

Introduction

Despite increasingly strident warnings from the scientific community about the impending impacts of anthropogenic climate change and almost universal acceptance of the role of human activities in these changes (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2014; Oreskes, 2004a), development of substantive policy to significantly reduce carbon emissions in Australia remains gridlocked. While the September 2015 ascendency of climate advocate Malcolm Turnbull to the prime ministership offered hope for a change in political attitudes and policy direction, to date, powerful voices of denialism continue to hold sway within the Australian government.

In this context, the dynamics of the debate and the role of media in shaping and influencing public and subsequent political attitudes on climate change are significant (Boykoff, 2011; Cox, 2010; Hansen, 2010; Lester & Hutchins, 2013; Painter, 2013). Boykoff (2011) for example, pointed to the weight given to media coverage by political actors that makes the study of media representations important. The pro-active role of conservative think-tanks in ‘organising denial’ (Oreskes & Conway, 2010; McKewon, 2012), the over-representation of climate contrarian views within powerful sections of the conservative media (Elsasser & Dunlap, 2013; Jacques, Dunlap, & Freeman, 2008; Manne, 2011; McKnight, 2010) and the ‘echo chamber’ effect of this confluence of views on public opinion, all impact the extent to which various forms of media set the agenda for debate and provide the impetus for policy formation on matters previously considered the realm of experts. Sociologists have labeled this the ‘denial countermovement’ (Dunlap & McCright 2015), a movement that has arisen spontaneously among groups within a society whose hegemonic power (economic, political, cultural and professional) is threatened.

A pervading rhetorical trope of media-based climate change denialism is that of the ‘climate sceptic’. While the over-representation of these views in Australian media has been previously identified and mapped (Bacon, 2013; McKnight, 2010), the specific manner in which ‘climate scepticism’ is working discursively within these media texts remains unclear. In particular, are the approaches and practices of these self-labeled ‘sceptics’ consistent with scepticism that is a traditional canon of empirical science? Further, to what extent has the authoritative guise of scepticism been appropriated as a convenient cloak to hide both the ideological wellspring of climate denialism while giving it rhetorical and popular legitimacy? In the unregulated court of public opinion where powerful opinion leaders and political and economic interests can use their influence to shape public opinion and impact political agendas in ways that serve their own interests, the ‘sceptic’ label acquires new meanings, new methods and new importance in this debate.

In order to explore this phenomenon more closely, this paper examines the writings of high profile conservative commentator Andrew Bolt as a case study in the construction of so-called ‘climate scepticism’ for the extent to which it is consistent with the traditional use of the term. The research uses a mixed methods approach that uses the insights afforded by the unique Leximancer text analytics software to explore a large dataset of Bolt’s writings for patterns and connections that extend analysis beyond the level of the more traditional ‘close reading’ approach to critical discourse analysis (CDA).

Andrew Bolt: A wolf in ‘sceptic’s’ clothing?

As a case study in media-generated climate scepticism, Andrew Bolt is worthy of study for a number of reasons. He is touted as having ‘Australia’s most read political blog’ and his regular newspaper column is syndicated in numerous Australian capital and regional newspapers. He hosts his own weekly television talk show, The Bolt Report, and has a weekly segment on radio 2GB. He is unapologetically partisan in his views and both his columns and his blog regularly lambast and deride the actions of ‘the Left’ while sparing any similar level of critique for the conservative side of politics. He makes little effort to adhere to the norms of journalist balance and his polemical style, it could be argued, is a characteristic that endears him to his audience.

In terms of the overall volume of populist ‘debate’ in Australia, Bolt plays a significant role as an agent of climate change denialism. Bacon’s (2011) study of Australian media coverage of climate change for example, estimated that Bolt accounted for almost half of the number of words in articles written on climate change, climate science and climate policy in the Murdoch-owned Herald Sun newspaper, 96% of which was negatively framed. In terms of his reach and impact, Crikey.com’s 2011 Power Index named Bolt as its number 1 ‘megaphone’, stating that:

No other commentator has been as successful at undermining public trust in the science of man-made climate change and whipping up opposition to a carbon tax (Knott, 2011).

Fig 1: Screen shot from Andrew Bolt’s blog http://blogs.news.com.au/heraldsun/andrewbolt/

The vociferousness of Bolt’s campaign against the global warming ‘orthodoxy’ and his crusade against the ‘hypocrisy’, ‘folly’ and ‘false prophesies’ of those he derides as ‘alarmists’, ‘warmists’ or ‘eco-fundamentalists’, is evidenced by the sheer number of daily blog posts and weekly columns dedicated to the topic. His fixation on climate change has been described by one commentator as a form of ‘religious fanaticism’ (Mayne, 2015). Andrew Bolt does not hold any university degree, let along one in science, yet he constructs the illusion of informed and rational engagement with the data by providing detailed explanations, references and graphs and by appropriating the language, jargon and authority of science to argue his views.

Bolt’s writings on climate change are illustrative of the tenor, tactics, rhetorical strategies and ideological worldviews of other self-labeled media ‘climate sceptics’ (e.g. Farmer & Cook, 2013; Leiserowitz, Maibach, Roser-Renouf, & Smith, 2010) and while it is difficult to assess his level of influence more broadly, Bacon (2011, p. 93) notes that given his ubiquitous media presence, Bolt likely ‘plays a significant and strategic role in the production of climate scepticism in Australia’. To this extent, the media have an important role as agents, as well as conveyors, of ideology.

But to what extent are Bolt and fellow anti-climate science commentators, ‘sceptics’ in the traditional sense of the term? The Leximancer analysis explores the language with which Bolt’s scepticism is constructed and the extent to which it is more politically than scientifically framed. It illustrates that Bolt’s rhetorical focus leans more strongly on the ideological leanings and political motives of climate change advocates and it does so as a vehicle through which to attack the legitimacy of the scientific evidence and arguments for urgent carbon abatement policies. His contra-‘evidence’ is sourced mostly from other contrarian blog sites as opposed to peer reviewed scientific journals and is usually cherry-picked, often misinterpreted and taken out of context. As a consequence, he has repeatedly been called out for his misuse of examples and quotes cited to support his assertions (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2006, 2011, 2013). For example, in December 2012, the Australian Press Council upheld a complaint about the manner in which Bolt, in a piece titled ‘Time that climate alarmists fessed up’ (February 1, 2012), had recycled a story about the UK Met Office without bothering to report the Met Office’s response that the data cited in the original article was misleading (Australian Press Council, 2012).

When is a ‘sceptic’ not a ‘sceptic’?

The Skeptics Society (2014) points out that ‘skepticism is a method, not a position’. Before describing the specifics of the research, it is useful therefore to overview the traditional role and function of ‘scepticism’, described by Bourdieu (1999) as one of science’s most sacred ‘methodological canons’ (p. 264).

In the classical discourse of science, scepticism is a tacit and desirable state of critical engagement. Science is advanced and evolved by the questioning of, and challenge to, its epistemology, forms of measurements, interpretations of data and the value ascribed to these measurements and interpretations (Herrick & Jamieson, 2001). Unlike mathematics, Naomi Oreskes argues (2004b, p. 369), ‘science does not provide logically indisputable proofs about the natural world’ but acts like:

… an ongoing courtroom drama, with a continual stream of evidence being presented to the jury. But there is no single suspect and new suspects regularly wheeled in. In the light of the growing evidence, the jury is constantly updating its view of who is responsible for the data (Lewis, 2014).

In other words, research continually evolves, its sources and methods questioned and its interpretations contested. Stephen Schneider further notes that:

In science … [t]here are rarely just two polar-opposite sides, but rather a spectrum of potential outcomes, which are often accompanied by a history of scientific assessment of the relative credibility of reach possibility (2009, p. 203).

The traditional ‘ideal’ view of science, and one through which much of its power and idealised authority historically has been generated, is of an activity or endeavour, separate from politics, in which knowledge is sought in a systematic and objective manner, ultimately for the public good. Science observes, measures and predicts, has systematic methods of selecting and testing hypotheses and uses multiple streams of enquiry, analysis and interpretation. It evaluates ‘evidence’ based on what is testable, measurable, observable and reproducible, and develops explanations based on, and often developed from, previous theories or explanations. Its method of enquiry has been described as a blend of logic and imagination (Rutherford & Ahlgren, 1991). According to one definition:

Science, in its purest sense, is not a worldview but a method for systematically investigating and organising aspects of reality that we access through our senses (McFarlane, 2002).

Like all intellectual endeavours, however, its foci and approaches are multi-faceted. As Merton (1973) and other more recent sociologists of science have argued (e.g. Kuhn, 2012; Latour, 2009; Woolgar, 1988), science is both a social institution and a cultural phenomenon. It is not conducted in a vacuum, and like all producers of knowledge, scientists are equally influenced and constrained by the historical context, institutional structures, power hierarchies, ideological and cultural norms in which they operate. Historically, the practices, debates and controversies of science have occurred largely on the periphery of mainstream public attention and have been characterised by a shared discourse and a common understanding of the nuances of methods, assumptions and interpretations of scientific research.

In recent decades, however, the emergence of complex new social and scientific phenomena (such as anthropogenic climate change) characterised by ‘high levels of uncertainty’ and higher levels of risk (Jacques, Dunlap, & Freeman, 2008) have challenged traditional knowledge paradigms and the reputation, efficacy and traditional authority of scientific method, its internal mechanisms and raison d’être. These pressures have impacted the public understanding of the formalisms of science. What Funtowicz and Ravetz (1993) have labeled ‘the post-normal age’ of science, has increasingly demanded a more ‘democratic’ and ‘transparent’ dialogue and critique of the social impacts, directions and ‘value’ of scientific endeavour and research priorities. There has also been a call for ‘stakeholders’ and other knowledge holders to participate in this discussion and for scientists to play a greater role ‘in the management of these crucial uncertainties’ (p. 742). In the case of major public health controversies such as smoking and vaccination, the effect has been to shift much scientific conversation into the broader public sphere and to shape the expectations of the populace more broadly in terms of their engagement in this conversation.

The challenges posed by an environmental issue such as climate change and the implications for the political and economic status quo of dealing with these, have further shifted these norms, leading to a much more overtly politicised public debate. The popularly espoused distinction between ‘sound science’ and ‘junk science’ (Baba, Cook, McGarity, & Bero, 2005), a dualism that portrays scientific method as both singular and universally identifiable, is an example of this shift. This dichotomy is not only empirically impossible to support given the sheer diversity of modern scientific activity, but one that seriously misrepresents the complexity and nuance of the scientific process (Edmond & Mercer, 1998; Herrick & Jamieson, 2001). It also disguises the extent to which internal differences and disagreements over methods and interpretations are the norm within the scientific community and the extent to which debate already exists.

In the public and political ‘debate’ over climate science and climate change policy, the traditional understanding of the term ‘sceptic’ also appears to have shifted. In our highly mediatized and participatory culture, enabled by new more technically sophisticated and democratic media platforms and unencumbered by traditional journalistic norms of fact checking and balance, the voices of experts and non-experts alike are considered of equal value (Keen, 2007). Anyone with strong views or a political or ideological ‘barrow’ to push is able to publish and the veracity or basis in evidence of these positions is rarely contested in what has been described an era of ‘post-truth’ politics and media (Ellerton, 2016; Viner, 2016). In the case of climate science, opposition to the publication of contrarian views is often seen as an attack by so-called ‘elites’ (Bolt, 2014; Delingpole, 2014) on the common sense views of ordinary people and an attempt to curtail their freedom of speech.

The specific interest of this paper is how climate scepticism is discursively constructed by those who, like Bolt, wear the label of ‘scepticism’ as a marker of their political and popular identity. It argues that the label has been deliberately appropriated to legitimise the views of those who contest the validity of empirical scientific evidence and its implications for proposed carbon abatement policies while ignoring the underlying principles of its praxis and scepticism’s traditional function within the epistemology of science. Research needs to track these changes as they are occurring via a range of voices across a broader number and dispersed set of texts and media platforms. This poses methodological challenges that require extending the scope and methods of close analysis that has traditionally been used for this purpose.

Methodology/Approach

From this perspective, this research has used a mixed methods approach to analyse a large sample of Andrew Bolt’s popular and widely read Herald Sun columns that specifically focus on climate change. These columns give both prominence and authority to Bolt as an anointed conservative political and social commentator. The research has used a combination both traditional qualitative ‘close reading’ and what literary critic Franco Moretti (2013) has labeled ‘distant reading’. Close reading as used in literary studies and in CDA more generally, is performed when individual texts are closely analysed for their linguistic style, organizational structure, use of rhetorical devices and semantic relationships to reflect and draw inferences from the significance of their discursive patterns. Conversation analysis or comparison of the discursive markers in specific political speeches for their approach to a similar topic is an example (e.g. Gurney, 2013).

One of the criticisms of qualitative methods generally, and CDA specifically however, is that the selection by the researcher of what appear to be interesting or pertinent examples through which to discern discursive patterns or frames may overstate their incidence and prominence – for example, during the 2013 federal election, while Kevin Rudd’s (2007) description of climate change as ‘the great moral challenge of a generation’ was frequently cited, it was used mainly as a pejorative in the context of the argued negative economic impacts of the Rudd/Gillard government policies rather than in relation to the moral or ethical perspective of climate change as a pressing policy issue (Gurney, 2014). For this reason, Moretti has argued the case for ‘distant reading’, a quantitative approach that uses some form of computer-aided analysis to search, identify, plot and discern patterns in big data sets that can then be more closely analysed for insight they may offer into the discursive structure of a particular genre or in this case, a particular author on a singular topic. In this project for example, distant reading highlighted both the extent to which scepticism in the Bolt corpus was politically rather than scientifically framed and the structural manner in which this was working across the corpus. While Bolt’s ideological bias is unsurprising, the specific way that his scepticism is constructed and the identification of underlying assumptions at its core, become much clearer, easier to identify and to analyse.

Given the extensive nature of Bolt’s writings on climate change, this study used the Australian-designed text analytics program Leximancer 4.0 that is gaining increased recognition for its application in both marketing and in academic research (for examples, see Cretchley, Gallois, Chenery, & Smith, 2010; Hodge & Matthews, 2011; Young, Wilkinson, & Smith, 2015). The Australian designers of the system describe it in this way:

The Leximancer system performs a form of automatic content analysis. The system goes beyond keyword searching by discovering and extracting thesaurus-based concepts from the text data, with no requirement for a prior dictionary (Smith & Humphreys, 2006, p. 262).

In other words, the relationality between themes and concepts is generated by the extent of their presence, co-occurrence and relative recurring proximity in the text corpus. While the software design is based on content analysis methodology, it does more than merely count the frequency of words. The underlying theoretical premise is that key concepts and themes are identifiable from the way that words travel together both directly and indirectly (Smith & Humphreys, 2006). For example, this analysis highlighted the extent to which concepts such as ‘warming’ and ‘scare’ as well as others such as ‘facts’ and ‘wrong’ are closely correlated in the corpus.

Further, because authors make both conscious and unconscious linguistic choices in terms of words chosen, the order in which words are used as well the rhetorical and metaphorical devices deployed, the ability to map these relationships across a large dataset provides the opportunity for both a broader overall perspective as well as more accurate and insightful interpretation that may not be possible with selective choice of isolated individual sample texts. In support of this, the developers argue that:

The process is deterministic and results in an explicit and reproducible coding that reflects the semantics and interrelationships present in the text. Use of Leximancer thus overcomes some of the problems qualitative researchers face, such as justifying their coding, intercoder reliability, and their interpretations (Young et al., 2015, p. 113).

A unique characteristic of Leximancer compared to other computer-aided software such as NVivo, is that the output allows a researcher to literally ‘see’ the conceptual connections from the perspective of both broad themes, the concepts with which these are composed and their relative proximity and conceptual structure. Interpretations can be verified by the functionality that allows you to interrogate the output at the level of the generating texts for the context, tone and semantic characteristics. For example, interrogating text samples generating concepts such as ‘science’, ‘facts’ and ‘evidence’ illustrated the extent to which Bolt uses these terms differently depending on the rhetorical objective and focus of the specific column. The legitimacy of ‘facts’ and ‘evidence’ is dependent on the source and the interpretation and the extent to which these support his views. While analysis the output is necessarily qualitative, the usefulness of Leximancer’s functionality is that it enables and:

… highlight[s] a visual approach to analysis which changes the way text is used as evidence and forms the basis for decision-making. [Computer-aided qualitative discourse analysis software applications] are an invaluable tool for semi-automating, flexibly organising and presenting the results of open, axial and selective coding of grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Moghaddam, 2006) and allied qualitative social research methods (Angus, Rintel, & Wiles, 2013, p. 262).

The combination of both close and distant reading methods using Leximancer therefore enables qualitative analysis to be generated from a quantitative base, taking advantage of the strengths of both approaches.

Leximancer mapping of the Herald Sun columns: Initial reading

A corpus of Bolt’s columns between the years 2001 and February 2015 was downloaded from the ProQuest ANZ Newsstand database using the search terms ‘climate’, ‘global warming’ and ‘scien*’ (kw), ‘Andrew Bolt’ (au) and Herald Sun (pub) and returned 617 results. The search specified the Herald Sun publication as these columns are syndicated in several other Australian major newspapers owned by News Limited but are often republished with different headlines. The ‘hits’ were edited to remove the identifying metadata and then uploaded into Leximancer 4.0 to map the conceptual relationships (Leximancer.com., 2014).

In Leximancer, the relative strength of the themes is determined by both the frequency of co-occurrences, their hierarchical order of appearance within the text segments and their relative proximity (Smith & Humphreys, 2006). The output is visually coded as a heat map, the ‘hottest’ or most prominent theme being in red, the ‘coolest’ or least strong, being in purple. The theme size can be adjusted from the default of 33% using a slider between 0-100%, the effect being to relocate the ‘concepts’ (which remain static) within either smaller, more specific themes, or larger, more general ones. This may result in some themes disappearing while new ones emerge. The theme and concept names are automatically generated and reflect the most frequent and semantically connected concepts within the corpus.

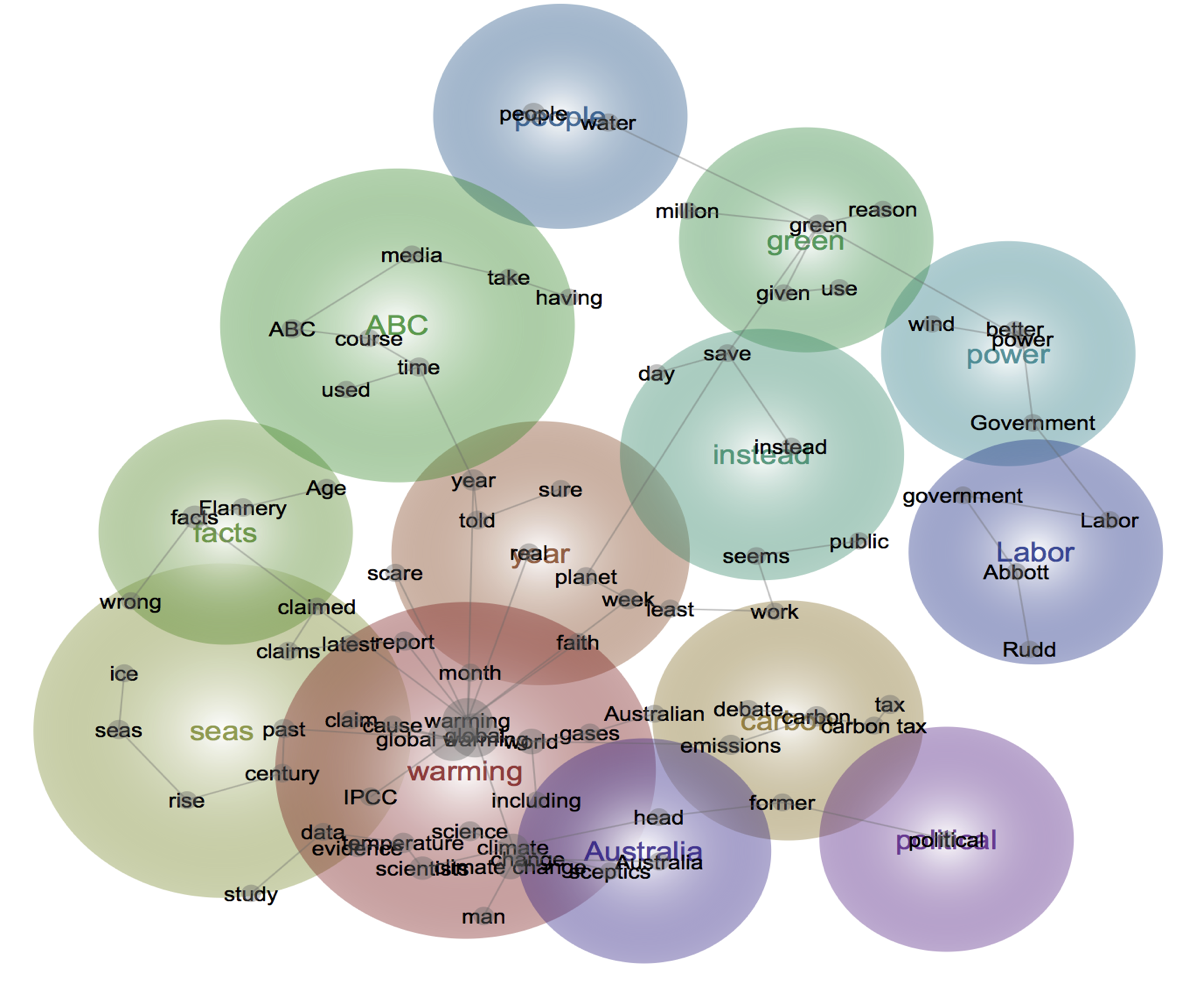

In the Bolt corpus, the most prominent theme was warming. It is important to note that Bolt uses the terms ‘global warming’, ‘warming’ and ‘warmists’ differently, the latter two expressed as derogatory rather than neutral labels. For this reason, the text-generated theme name warming rather than global warming is significant as it points to the dominant focus of this theme. Other themes in order of strength were year, carbon, seas, facts, ABC, green, instead, power, people, Labor, Australia and political. Figures 2 and 3 show screenshots of the initial output of the data at the default level of 33% as both a ‘concept map’ and ‘concept cloud’.

Within each theme, the most significant concepts can be identified by the size of the individual concept nodes. Related concepts appear as nodal clusters and these clusters and their relative proximity are important. Additionally, the strongest connections between the various concepts are represented by visible links similar to the way in which molecules in a chemical compound chain are represented.

Figure 2: Initial Leximancer concept map of Bolt column corpus set at theme size 33%

The composition of the clusters themselves and their relative spatial positioning indicate the substance of Bolt’s arguments and manner in which they are constructed. For example, the ‘warming’/‘global warming’/‘world’/‘cause’ cluster is illustrative of his repeated claim that temperature statistics showing the incremental trajectory of global temperatures are being misread and that there has been no warming since 1997 (e.g. ‘How much global warming is just fiddled data?’ 24 June, 2014). He regularly takes issue with the interpretation of the so-called ‘hockey stick graph’ (Mann, Bradley, & Hughes, 1998) which shows that the trajectory of warming has been higher than in any period since the 1400s, this is despite the fact that the robustness of this model has been variously verified (e.g. Wahl & Ammann, 2007).

The second major cluster incorporating the concepts of ‘data’/‘evidence’/‘climate’/‘temperature’ and so on, is spatially separate and is linked to the first cluster via ‘climate’ rather than ‘science’. In other words, this indicates that while the ‘cause’ of global warming is a regular theme, it is rarely discussed in the same frame as the ‘science’. In a similar way, the concept of ‘man’ is both on the periphery of the warming theme but is disconnected from both ‘science’ and ‘temperature’. This is indicative of the extent to which man’s responsibility for global warming is only remotely discussed in connection with either the science or the environmental impact.

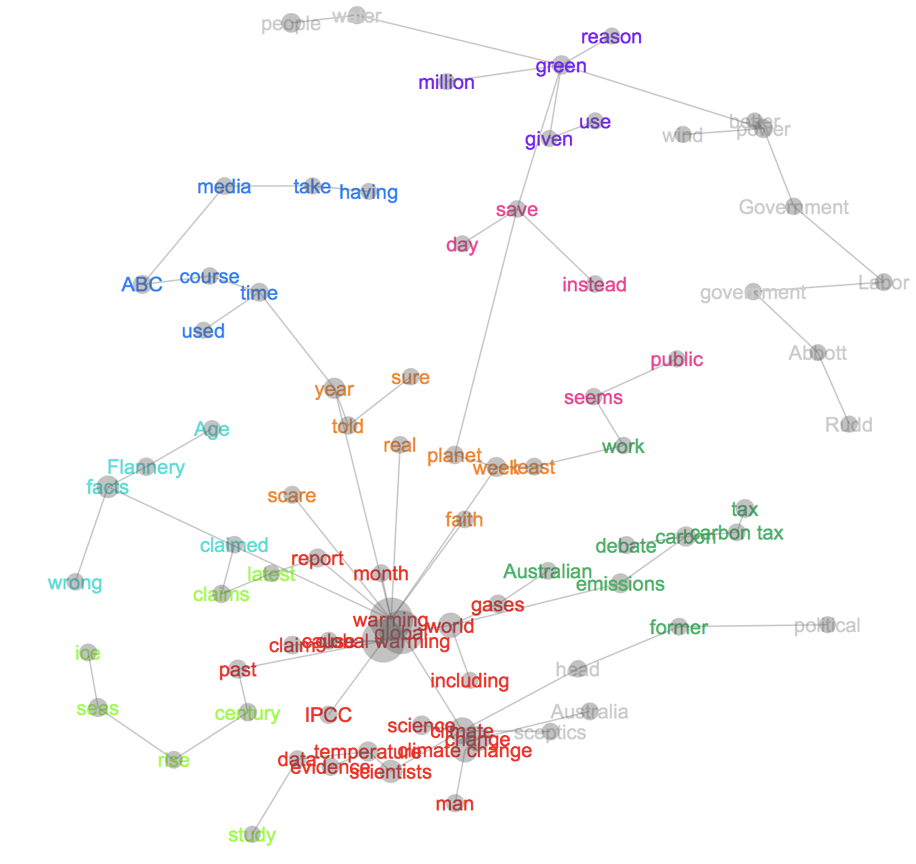

The alternate ‘concept cloud’ view (Fig 3) allows the relative spatial positioning of the concepts and the direct links emanating from the dominant themes to be seen more clearly. This is important because in Leximancer, while concepts may be spatially close, their strength (or disconnection) in the corpus also needs to be considered. From the perspective of the focus of this paper, what is most striking is the manner in which the concepts of ‘scare’, ‘tell’, ‘real’ and ‘faith’ in particular, radiate in a direct line from the various concepts closely clustered around ‘warming’. Further, the ‘IPCC’ (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) concept while directly linked to concepts around ‘global warming’, is spatially separate within the theme bubble. It has its strongest connection to the ‘warming’ concept cluster rather than to the ‘data’/‘evidence’ cluster. As noted earlier, Bolt uses the term ‘warming’ as a derogatory label. Text samples generating this concept indicate that the IPCC is repeatedly constructed as a political instrument rather than as a scientific body responsible for collating evidence in order to communicate about climate change. Bolt repeatedly accuses the IPCC of being involved in a conspiracy evidenced by ‘Climategate’ to fake scientific evidence for political purposes (e.g. ‘Climategate’s most damning emails’ 25 November, 2009). While this is not unexpected, it is illustrative of a consistent theme of the columns over the period of the data and the manner in which his ‘crusade’ against the ‘warmists’ is regularly rhetorically constructed.

Figure 3: Initial Leximancer ‘concept cloud’ of Bolt column corpus set at theme size 33%

Another of the initially dominant themes is carbon incorporating the concepts of ‘carbon’, ‘emissions’, ‘carbon tax’, ‘tax’ and ‘debate’. Again, while this is unsurprising given that climate change is being driven by excessive carbon emissions, when you inspect the sample text, the ‘debate’ in question relates to whether the science is ‘settled’ and the focus is predominantly on both Kevin Rudd’s proposed emissions trading scheme (ETS) in 2009 and Gillard government’s so-called ‘carbon tax’ introduced in 2011. Importantly, the Liberal Party’s alternative Direct Action policy is not present within the map, its absence evidence of the Bolt’s one-sided focus. A manual search of the corpus for discussion of Direct Action found only one mention of the Abbott government policy over the period of the columns with Bolt describing it as merely as ‘pointless as Labor’s’ (‘Abbott’s climate plan as bad as Labor’s’, 24 Oct, 2013), arguing that it too would merely impose economic costs but make no material impact on the world’s emissions. In each case, the ‘debate’ is framed in a simplistic, highly political and binary manner: ‘warmists’ versus ‘sceptics’, left versus right, elites versus the average man in the street, free speech versus ‘orthodoxy’. This is evidenced in the concept map by the proximity of the carbon theme to the political theme, which if you shift the theme size marginally to 40%, disappears and is subsumed into an enlarged carbon theme. Again, Bolt’s so-called ‘sceptical’ stance is more strongly politically than scientifically framed.

When is a ‘fact’ a fact?

The theme of ‘facts’ as it relates to Bolt’s ‘scepticism’ is highly pertinent although somewhat weaker within the initial concept map. The ‘concept cloud’ view shows that while there is a direct link between the concepts of ‘facts’ and ‘warming’, ‘facts’ is closer thematically to ‘Flannery’ (former Climate Commissioner Tim Flannery), ‘Age’ (the rival Fairfax newspaper), ‘claimed’ and ‘wrong’. What constitutes a ‘fact’ in climate science is important in Bolt’s discursive construction of ‘scepticism’, and the ‘facts’ around carbon emissions and their impacts are those that he most hotly contests. A fact is both positively and negatively framed, its legitimacy relative to the political or ideological leaning of the agent espousing the claim. In the related text, Bolt, for example, demands of Tim Flannery:

I mean, shouldn’t a scientist be in the facts business? (‘Tim’s Science Fiction’ 14 October, 2005). 1

The implication is that ‘facts’ or ‘evidence’ speaks for itself and that as a scientist, opinion or interpretation is inconsistent with scientific method. Similarly, in one of his numerous critiques of Al Gore and of ‘Climategate’ and the IPCC, Bolt argues in an ironic tone:

Yes, you trust Gore, this Nobel Prize laureate and Oscar winner when he tells you that the leaked emails from the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit don’t in fact show that the world’s most influential climate scientists used ‘tricks’ to ‘hide the decline’ in temperatures. You trust him when he also denies that they show this powerful clique of scientists destroying inconvenient data, committing fraud, censoring sceptical scientists and privately admitting to doubts about the warming theory they publically scream is settled (‘In Gore’s opinion, Climategate was only an inconvenient hiccup, 11 December, 2009).

The ‘facts’, as advanced by the ‘warmists’, are usually posited as either deliberate lies cooked up to scare the general public for a range of nefarious political, ideological or unethical scientific purposes, or are either misinterpretations or gross exaggerations that are easily countered by either the common-sense view (it’s snowing so where’s the warming?) or by Bolt’s countervailing ‘facts’. His ‘scepticism’ is most often predicated on the political motives of scientists as opposed to any particular, scientifically argued critique of methods or interpretations of evidence. His alternate ‘evidence’ most often revolves around the oft-repeated examples of ‘dud predictions’, an argument that simplistically ignores both the difference between climate and weather as well as the complexity of the Earth’s climate system. While casting derision on Gore’s, Flannery’s and the IPCC’s ‘facts’, Bolt is happy to uncritically promote the interpretations provided by those scientists, politicians or commentators with whom he agrees regardless of their expertise.

As discussed, moving the ‘visible concepts’ slider from zero to 100% provides a slightly different perspective from the original output map. Initially, the strongest concepts already noted appear in order of their strength within the corpus overall. However, at 14% the ‘facts’ concept (located within the facts theme) appears and at 16%, ‘carbon’ and ‘emissions’ (located within the carbon theme) appear before any of the remaining concepts in the stronger warming theme. This indicates that while these latter concepts are more strongly bonded to the localised concepts in their themes (rather like a magnetic field via their semantic relationships), they are stronger in terms of their presence in the corpus overall than some others in the stronger themes. In other words, ‘facts’ as a concept is more significant than it initially appears. Interestingly, it is located a long way from ‘evidence’ and from ‘sceptics’ indicating that Bolt constructs these separately.

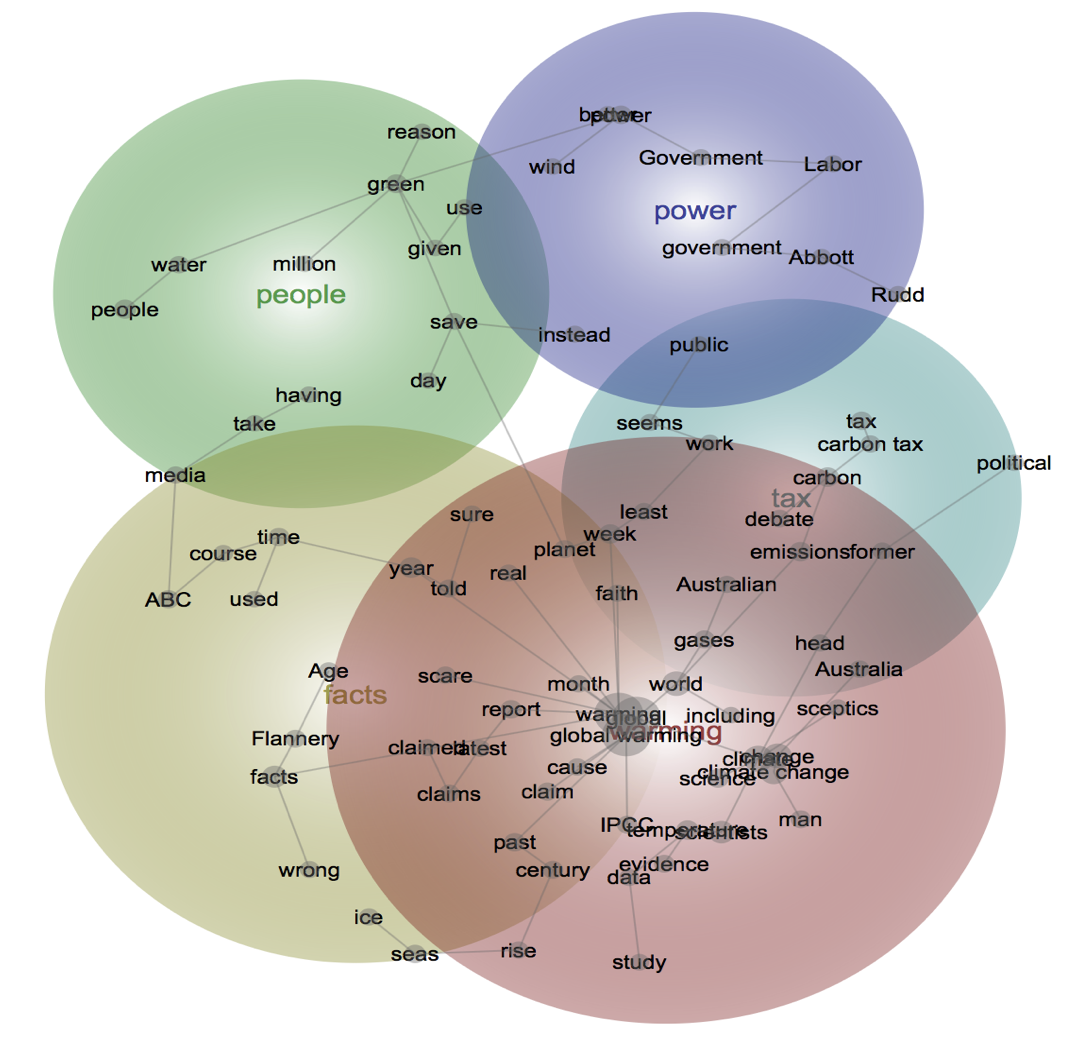

As you enlarge or reduce the theme size from the default 33%, the initial view of the relationship between the concepts and themes will alter, with some disappearing and new ones emerging. The concepts remain static but may be subsumed into the new larger or smaller themes. This is also a useful perspective. For example, when the theme size is enlarged to 60% (see Fig 4), the themes of warming and facts have a more significant overlap by encompassing concepts such as ‘scare’, ‘latest’, ‘real’, ‘told’ and ‘claims’. Additionally, the seas theme disappears and concepts including ‘ice’ and ‘seas’ and ‘ABC’ (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) become part of the facts theme. Bolt regularly contests the evidence of the melting of polar ice and of sea level rise and these are constructed as contestable ‘facts’, ‘scares’ and ‘claims’. The ABC is regularly derided by Bolt for its ‘leftist bias’ and in particular its failure to give equal time to ‘sceptics’ in its reporting, a claim not supported by regular audits of ABC content (Bodey, 2014). Bolt’s position here is also illustrative of Boykoff and Boykoff’s (2004, p. 125) contention that the norm of ‘journalistic balance’ in media reporting has meant equal weight is being given to unequal actors in the climate change debate leading to ‘a significant divergence of popular discourse from scientific discourse’.

Fig 4: Bolt concept map at 60% theme size

Finally, being able to map such a sizable sample of texts in ‘distant reading’, allows you to note what is absent as much as what is present. In this corpus, a notable absence is a concept of ‘environment’. A manual search indicated minimal use of the word although its derivatives such as ‘environmentalists’ and ‘environmental’ were occasionally present, usually negatively framed (e.g. ‘Green mania to cripple us’ 15 October, 2010). While ‘planet’ and ‘save’ are present, they are closely situated to other concepts connoting doubt such as ‘least’, ‘week’, ‘sure’ and ‘told’. This speaks to the strength of Bolt’s political and ideological framing as well as to the absence of a broader, more nuanced argument for ‘saving the planet’. His focus is on the supposed ‘inconsistencies’ in scientific evidence, economic ‘vandalism’ and ‘unnecessary’ inconveniences of carbon abatement policies. A notable long running rejoinder of the blog posts, for example, is ‘Save the planet: …’, a headline always accompanied by an ironic subtitle:

Save the planet! Exterminate the camels (11 June, 2011).

Save the planet! Check termite farts (26 May, 2009).

Save the planet! Pass on your vibrator to a stranger (12 February, 2010).

The tone, much like the labels of ‘warmists’ and ‘eco-fundamentalists’, acts like a form of ironic in-joke to knowing readers laughing at the absurd preoccupations of these out of touch and self serving ‘elites’.

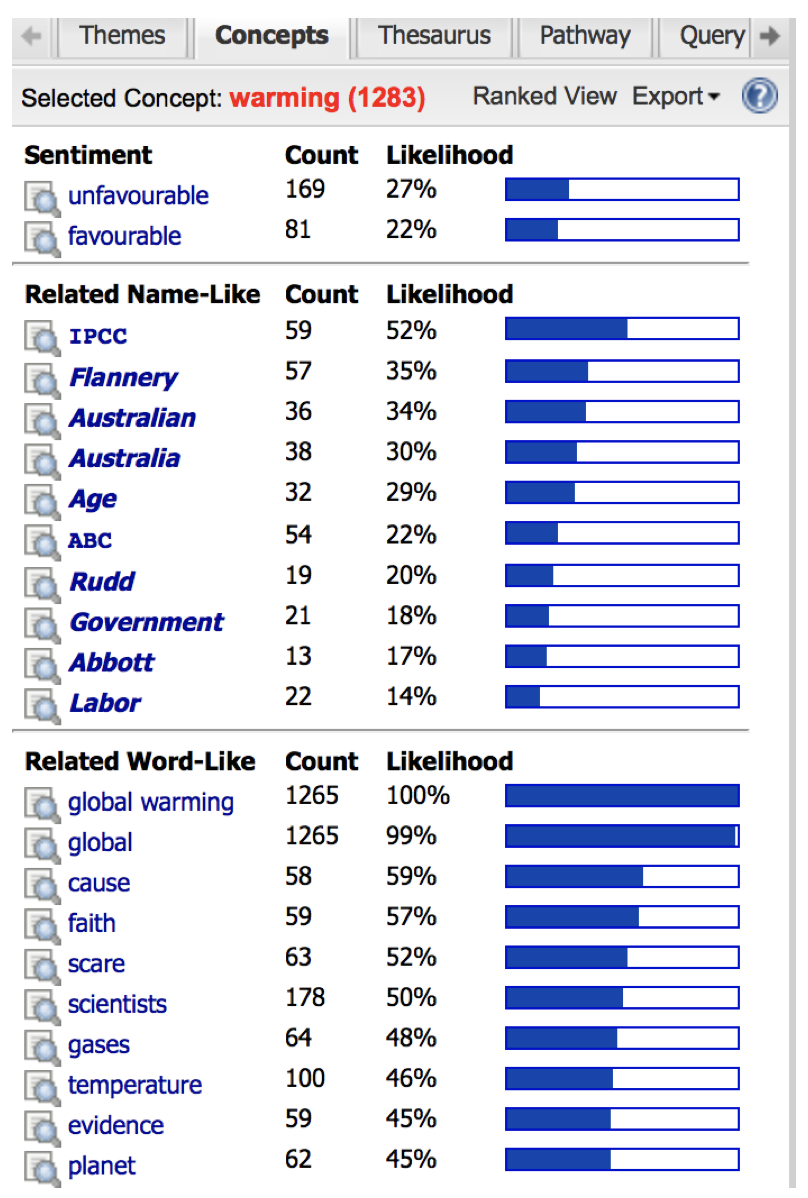

Examining the Bolt columns through the ‘sentiment lens’

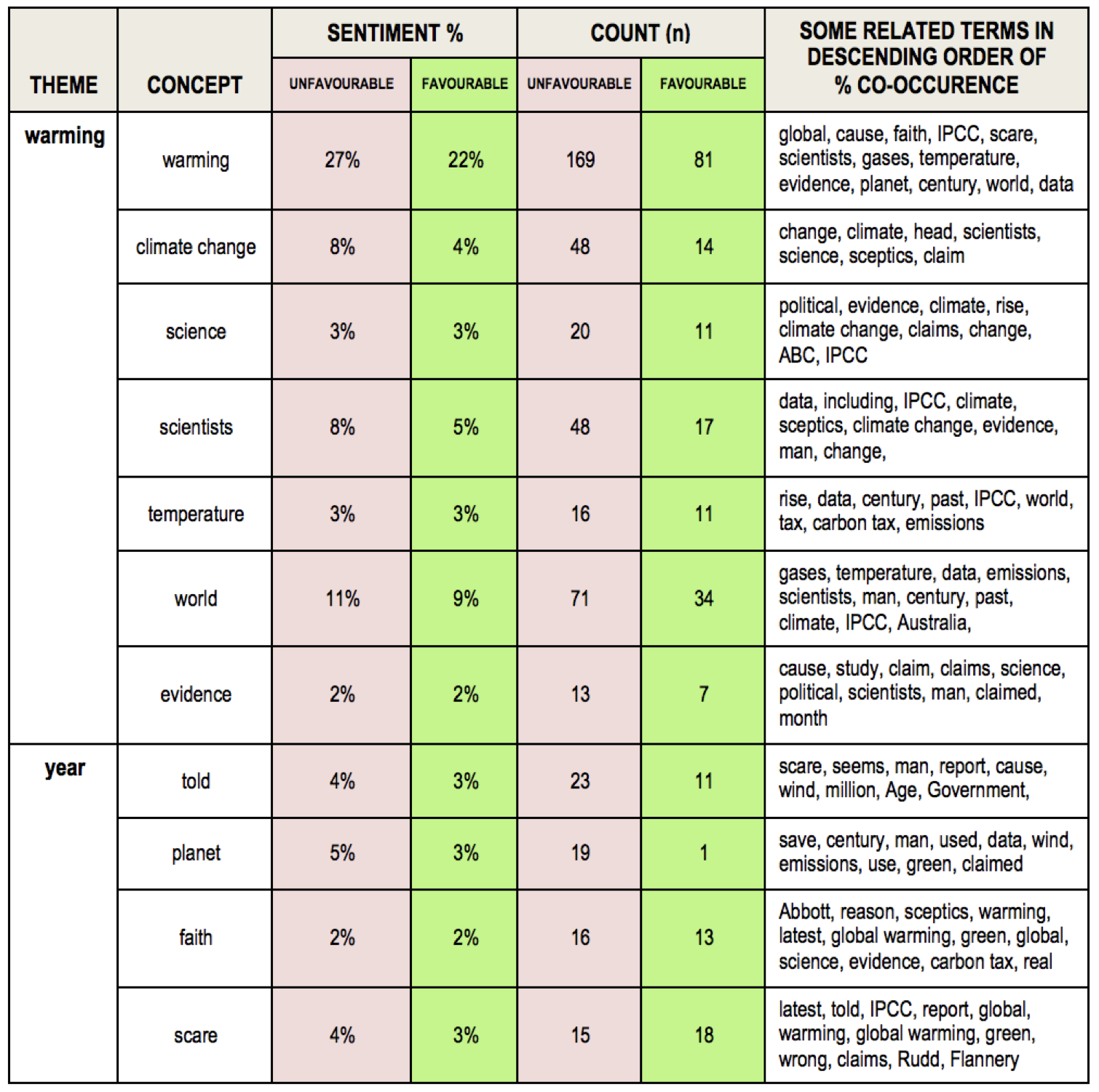

The ‘sentiment lens’ function of Leximancer measures the relative strength of positive (favorable) and negative (unfavorable) sentiment related to concepts and words within a data set as measured by a z-score. Table 1 gives a snapshot of the comparative sentiment of some important concepts in question with samples of the keywords with which they are most frequently related. The count is the raw number of times that concepts and words co-occur in the corpus. The related terms indicate the extent of their co-occurrence in order of strength with other concepts. It is also possible to drill down into the corpus to examine the text generating the output in order to interrogate and verify the context of these relationships. While the results of this function should be read as more representational than exact, they offer a useful perspective as they illustrate the comparative relative sentiment leaning of concepts within their semantic context and confirm what may otherwise be intuitions, particularly in a large data set. In the case of the Bolt corpus, the sentiment leanings of a number of key concepts, shifts according to the manner in which they are rhetorically deployed.

As shown in Table 1, while there is a significant difference in the measured sentiment leanings of some concepts that speaks for itself (e.g. ‘climate change’, ‘warming’, ‘scientists’), others are less obvious. In the thematic table snapshot (Fig 5) that more specifically lists the relative level of the sentiment for various concepts, ‘warming’ for example, is shown to occur 100% of the time with ‘global warming’, meaning that these two concepts always travel together. As noted earlier, Bolt uses the terms differently, ‘warming’ as an ironic rhetorical label to convey shared derision with his knowing readers. Additionally, ‘warming’ occurs 57% of the time with ‘faith’ and 52% of the time with ‘scare’. ‘Science’ is more strongly negatively related to ‘political’, ‘evidence’, ‘climate’ and ‘rise’ and so on.

Fig 5: Screenshot of Sentiment lens thematic table

In the context of how scepticism and science are framed, one of the dominant pejoratives cast at the ‘warmists’, is that they are espousing a ‘faith’. This is a recurring motif and one that I will discuss further as it relates to the discursive construction of ‘facts’ and ‘science’. In the link between ‘Abbott’ and ‘faith’ for example, Bolt uses the term ‘faith’ favourably when discussing the personal virtue inherent in Tony Abbott’s beliefs, or to chastise opponents who have derided him for his overt Christianity (his nickname being ‘the mad monk’).

This laugh-at-the-Jesus-freak party then raged on over at the websites of The Age and SMH, where covens of warming bigots howled at Abbott’s claim, convinced by their deepest prejudices that he must be wrong. … And why did hundreds of Age and SMH readers, on hearing the truth from Abbott, scream that he was blinded by his mad faith? Bigotry is on the hoof, I’m afraid, whipped on by a new faith more hostile to truth than is Abbott or any other good Christian (‘Warmists toast Abbott on the fires of their bigotry’, 12 May, 2010).

Table 1: Output of sentiment leanings of key concepts and related words

In contrast, ‘faith’ is used pejoratively in the context of what Bolt argues is the ‘orthodoxy’ of those who accept the science of global warming, the need to implement carbon reduction measures, or any need to ‘save the planet’. Abbott’s religious faith is cited as evidence of his ‘grounded’ conservative perspectives, in comparison with those of the ‘covens of warming bigots’ espousing the ‘warmist faith’ framed in one sense as just another fashionable hobbyhorse, and in another as a dangerous ideology with totalitarian aspirations. In a blog post that generated a record 311 comments, Bolt cites former Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Cardinal George Pell, on the science of global warming. In this context, religious faith is a virtue, but ‘faith’ in the authority of climate science is a sin, unless it supports the sceptical position.

Cardinal George Pell can recognise a religious movement when he sees one, and being a rationalist can also see where the global warming faith is weak: ‘The complacent appeal to scientific consensus is simply one more appeal to authority, quite inappropriate in science or philosophy.’ (‘Cardinal spots the green sins against reason’, 27 Oct 2011).

In the Bolt narrative, ‘sceptics’ are often framed as persecuted dissidents, as martyrs to science and reason and akin to Galileo for daring to question the prevailing orthodoxy – a curious analogy since Galileo’s views ultimately triumphed because they were supported by observation rather than blind belief. Those who question ‘sceptics’ are variously described as part of a ‘cargo cult’ and with a ‘green totalitarian itch’, guilty of ‘groupthink’ and seeking to unilaterally impose their ‘eco-fundamentalist’, ‘anti-humanist’ views to restrict personal freedoms – whether these be to drive cars, to eat meat, to exploit resources or to pursue individual economic advancement. The repeated use of religious metaphors is an interesting inversion of the framing of science and religion: science is accused of imposing penances for traducing its orthodoxies. Those who argue that the science of global warming is settled are ‘bigots’. Environmentalism is anti-humanist as it threatens to restrict personal freedoms.

This argument is further extended to conflate attempts to dismiss the alternate view in the light of overwhelming scientific evidence as an attempt to limit of freedom of speech, thought and action. Again, this is framed as an ideological position in Bolt’s writing.

YET I think we have here an insight into a key failing of so many grand schemes of the Left to improve resistant humans or build for them someone else’s idea of the perfect society. … What a buzz for the closet totalitarian then, to bully other people “for their own good” in this case, to “save the planet” [author’s highlights] (‘Norfolk Island green ration is ludicrous’, 3 Nov, 2010).

Like ‘faith’, ‘science’ is treated both favorably and unfavorably depending on the agent arguing for its authority to be respected. When citing examples of contrary ‘evidence’, usually conveniently cherry-picked and often sourced from other sceptical websites as opposed to peer-reviewed journals, science is framed as reliable and evidence-based. However, when climate scientists, politicians or journalists promote the cited 97% consensus view, science is accused of having been corrupted, its traditional raison d’être ‘slimed’.

But in science, how can anyone be neutral about truth? If Peacock concludes GM crops are safe, those who disagree shouldn’t say he’s biased, but prove him wrong. Except he’s not, is he? How many scientific debates are corrupted like this? Well, the one on man-made global warming for a start [author’s highlights]. Science must be saved from brawls in which dissenters are damned, not disproved. We must say no to the green slime (‘No rhyme to this kind of slime’, 17 Mar, 2006).

‘Proof’, ‘facts’, ‘evidence’ and ‘faith’ are malleable concepts depending on your ideological worldview, science is a matter of right or wrong and uncertainty or disagreement among scientists is proof of their fallibility and justification for inaction. All views, from experts and non-experts alike, are of equal value and deserve the same level of respect without regard to the authority of the sources or the validity of the scientific evidence upon which the opinions are based. His favoured ‘experts’ are either not scientifically qualified (Christopher Monckton is a journalist and conservative politician), do not have specific expertise in climate science (Ian Plimer is a geologist), or are aligned with conservative think tanks because of a professional and ideological agenda (see discussion of Bolt favourite Richard Lindzen by Lahsen, 2013). In terms of Bolt’s arguments for the ‘authority’ of the views he espouses, expertise in climate science should be challenged because:

Climate science … is the science where one plus one can equal three one day and six the next – yet never may the layman question the expert … This must change, and I believe finally is. The tyranny of the experts is now crumbling. The common sense view of the layman is at last being restored (Bolt, 2014, p. 274).

Conclusion

The Leximancer analysis of Bolt’s columns illustrates how he uses science and the label of ‘sceptic’ as a rhetorical vehicle through which to give authority to his views but in ways that are inconsistent with the genuine notion of scientific scepticism. As the sentiment lens illustrates, science and scientists are lauded and defiled according to their position on climate change as opposed to the strength and rigor of the evidence upon which their claims are based. Bolt argues that he is not a ‘denier’ (a label he finds offensive as it connotes ‘holocaust deniers’), but when he does reflect on his scepticism, the conflation of arguments is indicative of the ideological wellspring of his position – one to which he appears deliberately blind, although he happily highlights the impact of others’ ideological leanings.

Few sceptics doubt the planet has warmed over the past century, a century in which we’ve actually grown richer and healthier. The argument is whether man’s emissions are mostly to blame, whether the warming is dangerous and whether the pain of “stopping” it is worth the gain (‘If this is the best argument for the tax, we’re in strife’, 9 November, 2011).

Like Tony Abbott who stated that his government would not put the ‘environment ahead of the economy’ (AAP, 2015), these are positioned as separate and competing arenas, an argument inconsistent with the views of a large number of high profile economists including the former head of the Australian Treasury, Dr. Martin Parkinson, former head of the Reserve Bank, Bernie Fraser, and most notably the UK’s Lord Nicholas Stern and Australia’s Professor Ross Garnaut.

Science has a responsibility to be neutral, objective and non-political and judged with reference to the authority of those agents making the claims and the established rules of evaluation such as peer review. Yet according to Bolt and other media sceptics, all claims, all evidence regardless of its source, methods by which these views are obtained or expertise of the agents, should be considered of equal or zero value – one of the Leximancer analyses most important features is the ability to generate data that exposes the relationality and hence values of politically-based rhetorical calls for neutrality and balance. Science is called upon to be rational, neutral and evidence-based, but no such responsibility is required of those media personalities who opinions must also be heeded.

With regard to his position on climate change Bolt has said:

I know that there is a debate about [humans causing the warming of the planet] – that’s all I am prepared to say. I’m not a scientist but when someone tells me that all the scientists agree, I say no they don’t. They all agree that there’s a tendency for human emissions to heat the planet, but whether that’s responsible for all the heating is an open question (Hutcheon, 2014).

While he positions himself as ‘an Australian who respects reason and evidence’ (‘Join our global conspiracy, 13 November, 2009), his scepticism is constructed using two competing and contradictory discourses – democratic rights to freedom of speech versus the authority of expert scientists and the impunity of scientific method and rules of evidence. In addition, the labeling of the consensus of climate science as a religious ‘faith’ is used rhetorically to diminish its authority as illustrated by the sentiment lens analysis, an ironic position from someone for whom the convictions of Christian faith are purportedly important. Religious faith and ‘faith’ in peer-reviewed scientific evidence are not being judged by the same rules or logic.

While beyond the scope of this discussion, various studies have investigated the role of psychology and ideology in climate change denialism (e.g. Bliuc et al., 2015; Leiserowitz et al., 2010; Rossen, Dunlop, & Lawrence, 2015). In the case of climate science for example, Jacques (2006, p. 78) describes environmental scepticism as ‘a project that is skeptical of mainstream environmental claims and values but very faithful (i.e. not skeptical) to contemporary conservative values and issues’, including unquestioned faith in the efficacy of free markets and the inviolability of unfettered economic growth. Environmental protection and human progress are framed as antithetical goals. The role of ideology in shaping these views is not acknowledged. The various tactics summarised by Farmer and Cook (2013) serve to both muddy the waters of media-led debate but to create doubt about the level of consensus that exists, a factor identified as pivotal in broad public acceptance of the science and the policy implications (Ding, Maibach, Zhao, Roser-Renouf, & Leiserowitz, 2011; van der Linden, Leiserowitz, Feinberg, & Maibach, 2015).

Finally, many media-based ‘sceptics’ assert that opinion and evidence in the case of climate science are of equal value, and opposition to publication of contrary views contravenes free speech. According to Stokes (2012), this argument confuses the right to hold and express personal opinions with the claim that all alternative views are equally valid, regardless of the evidence. ‘Sceptics’ like Bolt ignore the fact that expert debate does occur within science and that the oft-cited consensus position on anthropogenic climate change has been repeatedly verified (Cook et al., 2013; Oreskes, 2007). The implications of climate science are unpalatable, it has been argued (Hamilton, 2010; Manne, 2012; Rossen et al., 2015), because they challenge fundamental premises upon which neo-liberal capitalism is based: an unrestrained free market and the right to mastery over nature for the sole benefit and advantage of humans. Much of the attack on the credibility of climate scientists, their public and political supporters and of policies which seek to address one of the most significant challenges of the human era, is an objection to the economic and political implications rather a systematic evaluation of the methods or critical analysis of the interpretation of the scientific studies in question.

Notes

1 Text samples from the Bolt columns and blog cite the title and publication date. All can be found at http://blogs.news.com.au/heraldsun/andrewbolt/

References

AAP. (2015). Tony Abbott: government will not ‘put the environment ahead of the economy’ The Guardian Australia, (11 August). http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/video/2015/aug/11/emissions-reduction-environment-economy-tony-abbott-video

Angus, D., Rintel, S., & Wiles, J. (2013). Making sense of big text: a visual-first approach for analysing text data using Leximancer and Discursis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(3), 261-267.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2006). Bolt’s minority view. Media Watch, (30 October). http://www.abc.net.au/mediawatch/transcripts/s1777013.htm

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2011). It’s elementary, my dear Bolt. Media Watch, (4 April). http://www.abc.net.au/mediawatch/transcripts/s3181944.htm

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2013). Hot air stoking the climate change ‘debate’. Media Watch, (24 June). http://www.abc.net.au/mediawatch/transcripts/s3788649.htm

Australian Press Council. (2012). Adjudication No. 1558: Ellett and others/Herald Sun (December 2012). http://www.presscouncil.org.au/document-search/adj-1558/?LocatorGroupID=662&LocatorFormID=677&FromSearch=1

Baba, A., Cook, D. M., McGarity, T. O., & Bero, L. (2005). Legislating ‘sound science’: the role of the tobacco industry. American Journal of Public Health, 95(S1), S20-S27.

Bacon, W. (2011). Sceptical Climate Part 1: Media coverage of climate change in Australia 2011. http://imlweb04.itd.uts.edu.au/acij-ds/investigations/detail.cfm?ItemId=29219

Bacon, W. (2013). Sceptical Climate Part 2: Climate science in Australian newspapers. http://investigate.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Sceptical-Climate-Part-2-Climate-Science-in-Australian-Newspapers.pdf

Bliuc, A-M., McGarty, C., Thomas, E. F., Lala, G., Berndsen, M., & Misajon, R. (2015). Public division about climate change rooted in conflicting socio-political identities. Nature Climate Change, 5(3), 226–229. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2507

Bodey, M. (2014). Audits exonerate ABC over bias claims, The Australian. Retrieved from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/media/audits-exonerate-abc-over-bias-claims/story-e6frg996-1226852398864

Bolt, A. (2014). False prophets unveiled. In A. Moran (Ed.), Climate change: The facts 2014 (pp. 274-285). Melbourne, Vic: Institute of Public Affairs.

Bourdieu, P. (1999). The Specificity of the Scientific Field. In M. Biagioli (Ed.), The Science Studies Reader (pp. 31-50). New York: Routledge.

Boykoff, M.T. (2011). Who speaks for the climate? Making sense of media reporting on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boykoff, M.T. (2013). Public enemy no. 1? Understanding media representations of outlier views on climate change. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(6), 796-817.

Boykoff, M.T., & Boykoff, J.M. (2004). Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press. Global Environmental Change, 14(2), 125-136.

Cook, J., Nuccitelli, D., Green, S., Richardson, M., Winkler, B., Painting, R., Way, R., Jacobs, P, & Skuce, A. (2013). Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters, 8(2), 1-8.

Cox, R. (2010). Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Cretchley, J., Gallois, C., Chenery, H., & Smith, A. E. (2010). Conversations between carers and people with schizophrenia: a qualitative analysis using Leximancer. Qualitative Health Research, 20(12), 1611-1628. doi: 10.1177/1049732310378297.

Delingpole, J. (2014). Experts as ideologues. In A. Moran (Ed.), Climate change: The facts 2014 (pp. 134-145). Melbourne, Vic.: Institute of Public Affairs.

Ding, D., Maibach, E., Zhao, X., Roser-Renouf, C., & Leiserowitz, A. (2011). Support for climate policy and societal action are linked to perceptions about scientific agreement. Nature Climate Change, 1 (December 2011), 462-466. doi: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1295

Dunlap, R.E., & McCright , A.M. (2015). Challenging climate change: The Denial Countermovement. In R. E. Dulap & R. J. Brulle (Eds.), Climate change and society: Sociological perspectives (pp. 300-332). New York: Oxford University Press.

Edmond, G., & Mercer, D. (1998). Trashing ‘Junk Science’. Stanford Technology Law Review, 1998(3).

Ellerton, P. (2016). Post-truth politics and the US election: Why the narrative trumps the facts. The Conversation. Available from https://theconversation.com/post-truth-politics-and-the-us-election-why-the-narrative-trumps-the-facts-66480

Elsasser, S., & Dunlap, R. E. (2013). Leading voices in the denier choir: Conservative columnists’ dismissal of global warming and denigration of climate science. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 754-776.

Farmer, G., & Cook, J. (2013). Understanding climate change denial Climate Change Science: A Modern Synthesis (Vol. 1 – The Physical Climate, pp. 445-466). New York: Springer.

Funtowicz, S.O., & Ravetz, J.R. (1993). Science for a post-normal age. Futures, 25(September), 739-755.

Gurney, M. (2013). Whither ‘the moral imperative’? The focus and framing of political rhetoric in the climate change debate in Australia. In L. Lester & B. Hutchins (Eds.), Environmental Conflict and the Media (pp. 187-200). New York: Peter Lang.

Gurney, M. (2014). Missing in action? The ‘non’-climate change debate of the 2013 Australian federal election. Global Media Journal-Australian Edition, 8(2). http://www.hca.uws.edu.au/gmjau/?p=1194

Hamilton, C. (2010). Requiem for a Species: Why we resist the truth about climate change. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Hansen, A. (2010). Environment, media and communication. New York: Routledge.

Herrick, C. N., & Jamieson, D. (2001). Junk science and environmental policy: obscuring public debate with misleading discourse. Philosophy and Public Policy Quarterly, 21(2/3), 11-16.

Hodge, B., & Matthews, I. (2011). New media for old bottles: Linear thinking and the 2010 Australian election. Communication, Politics & Culture, 44(2), 95-111.

Hutcheon, J. (2014). One plus one: Andrew Bolt. (21 February). http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-02-21/one-plus-one-andrew-bolt/5282174

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2014). Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/syr/SYR_AR5_SPM.pdf

Jacques, P.J. (2006). The rearguard of modernity: Environmental skepticism as a struggle of citizenship. Global Environmental Politics, 6(1), 76-101.

Jacques, P.J., Dunlap, R.E., & Freeman, M. (2008). The organisation of denial: Conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism. Environmental Politics, 17(3), 349-385.

Keen, A. (2007). The cult of the amateur: How blogs, MySpace, YouTube, and the rest of today’s user-generated media are destroying our economy, our culture, and our values. New York: Doubleday

Knott, M. (2011). Megaphones no 1: Andrew Bolt. Crikey.com, (20 July). http://www.thepowerindex.com.au/megaphones/andrew-bolt

Kuhn, T.S. (2012). The structure of scientific revolutions (4th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Lahsen, M. (2013). Anatomy of Dissent: A Cultural Analysis of Climate Skepticism. American Behavioral Scientist,, 57(6), 732-753.

Latour, B. (2009). Politics of nature: How to bring the sciences into democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., & Smith, N. (2010). Global Warming’s Six Americas. Yale Project on Climate Change. http://www.climatechangecommunication.org/images/files/intro_to_6_ams.pdf

Lester, L., & Hutchins, B. (Eds.). (2013). Environmental Conflict and the Media. New York: Peter Lang.

Lewis, G. (2014). Where’s the proof in science? There is none. The Conversation, (24 September). http://theconversation.com/wheres-the-proof-in-science-there-is-none-30570

Leximancer.com. (2014). Retrieved 2 August, 2014, from http://info.leximancer.com

Mann, M., Bradley, R., & Hughes, M. (1998). Global-scale temperature patterns and climate forcing over the past six centuries. Nature, 392(6678), 779-787.

Manne, R. (2012). A dark victory: How vested interests defeated climate science. The Monthly, (August 2012), 22-29. http://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2012/august/1344299325/robert-manne/dark-victory

Manne, R. (2011). Bad News: Murdoch’s Australian and the shaping of the nation. Quarterly Essay, 43, 1-119.

Mayne, S. (2015). Herald Sun climate travel hypocrisy exposed. Crikey.com, (20 Feb). http://www.crikey.com.au/2015/02/20/mayne-herald-sun-climate-travel-hypocrisy-exposed/

McFarlane, T. (2002). Questioning the scientific worldview. http://www.integralscience.org/questioning.html

McKewon, E. (2012). Talking points ammo: The use of neo-liberal think tank fantasy themes to delegitimise scientific knowledge of climate change in Australian newspapers. Journalism Studies, 13(2), 277-297

McKnight, D. (2010). A change in the climate? The journalism of opinion at News Corporation. Journalism, 11(6), 693-706.

Merton, R.K. (1973). The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and empirical investigations. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

Moretti, F. (2013). Distant reading. London: Verso Books.

Oreskes, N. (2004a). Beyond the ivory tower: The scientific consensus on climate change. Science, 306(5702), 1686.

Oreskes, N. (2004b). Science and public policy: What’s proof got to do with it? Environmental Science & Policy, 7(5), 369-383.

Oreskes, N. (2007). The scientific consensus on climate change: How do we know we’re not wrong? In J. DiMento & P. Doughman (Eds.), Climate change: What it means for us, your children, and our grandchildren (pp. 65-100). Cambridge, Massachusetts MIT Press.

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E.M. (2010). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. London: Bloomsbury.

Painter, J. (2013). Climate Change in the Media: Reporting risk and uncertainty. London: IB Tauris.

Rossen, I., Dunlop, P., & Lawrence, C. (2015). The desire to maintain the social order and the right to economic freedom: Two distinct moral pathways to climate change scepticism. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42, 42-47.

Rudd, K. (2007). Climate Change: Forging a new consensus. Paper presented at the National Climate Change Summit Parliament House Canberra. http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au:80/parlInfo/download/media/pressrel/H4OM6/upload_binary/h4om62.pdf

Rutherford, F. J., & Ahlgren, A. (1991). The Nature of Science Science for All Americans Online. USA: Oxford University Press.

Schneider, S. H. (2009). Science as a contact sport: Inside the battle to save Earth’s climate. Washington DC: National Geographic Books.

Smith, A. E., & Humphreys, M. S. (2006). Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behavior Research Methods, 38(2), 262-279.

Stokes, P. . (2012). No, you’re not entitled to your opinion. The Conversation, (5 October). https://theconversation.com/no-youre-not-entitled-to-your-opinion-9978

Talberg, A., Hui, S., & Loynes, K. (2013). Australian climate change policy: a chronology. Department of Parliamentary Services: Retrieved from http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/2875065/upload_binary/2875065.pdf.

The Skeptics Society. (2014). A Brief Introduction. Retrieved 9 December 2014, from http://www.skeptic.com/about_us/

van der Linden, S.L., Leiserowitz, A., Feinberg, G., & Maibach, E. (2015). The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change as a Gateway Belief: Experimental Evidence. PLoS ONE, 10(2), 1-8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118489

Viner, K. (2016). How technology disrupted the truth. The Guardian, (12 July 2016). https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/jul/12/how-technology-disrupted-the-truth

Wahl, E., & Ammann, C. (2007). Robustness of the Mann, Bradley, Hughes reconstruction of Northern Hemisphere surface temperatures: Examination of criticisms based on the nature and processing of proxy climate evidence. Climatic Change, 85(1-2), 33-69.

Woolgar, S. (1988). Science, the very idea. London: Routledge.

Young, L., Wilkinson, I., & Smith, A. E. (2015). A scientometric analysis of publications in the Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 1993–2014. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 22(1-2), 111-123.

About the author

Myra Gurney is a Lecturer in communication and professional writing in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts at Western Sydney University. She has recently submitted her Ph.D. (by thesis publication) titled ‘The great moral challenge of our generation: The language, discourse and politics of the climate change debate in Australia 2007-2017’. This paper represents one of the publication chapters.