The motifs of the arabesque in Pale Fire

Fatima Tefaili

Western Sydney University

Abstract

This paper examines the decorative motifs of the arabesque, an Islamic art form, in Vladimir Nabokov’s (1899-1977) postmodern novel Pale Fire (1962). The arabesque integrates different shapes and patterns to produce a single ornament containing symmetric, repetitive and kaleidoscopic motifs. It also produces a single continuous line that interweaves the various elements into an unbounded unified whole. The first half of the paper outlines the development of the arabesque, the geometric logic of which has been derived by Islamic scholars from Euclid’s Elements of Geometry. It discusses how the geometric concepts of the arabesque contribute to Pale Fire’s symmetric structure as well as the significance of Islamic calligraphy in Arabic aesthetics, namely in the 1001 Arabian Nights tales. As the evolution of the arabesque into literary style was adopted by Nabokov as a postmodern aesthetic, the second half of this article notes the elements of the arabesque in Pale Fire which include symmetry, reflections, mirroring forms, kaleidoscopic effects, repetition, continuity, circulation and an unending structure. The incorporation of the decorative motifs of the arabesque therefore allows us to read and analyse Pale Fire as a literary arabesque.

Introduction

This paper reads Vladimir Nabokov’s postmodern novel Pale Fire (1962) as a literary arabesque. Some of the motifs of an arabesque include symmetry, reflections, refractions, kaleidoscopic imagery, repetition, fragmented wholeness, circulation and continuity. Phraseology is also another technique used by authors of literary arabesques. Nabokov incorporated these motifs in his postmodern novel. The significance of incorporating characteristics of the arabesque into the structure of a novel is that it allows the novel to imitate the real arabesque ornament and produce an imagined arabesque in text form. This paper explores this writing style by using examples from Nabokov’s literary arabesque, Pale Fire.

Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) is a Russian writer who migrated from Russia in 1919 to western Europe, England, then later to Germany and France, before fleeing to America in 1940 (Boyd, 1991, p11). His father was assassinated in 1922 while ‘defending his chief ideological opponent within his own liberal Constitutional Democratic party’ (Boyd, 1993, p.6, 8). The memory of his father’s death is echoed in Nabokov’s novels, particularly the accidental murder of the poet, John Shade, instead of the intended target, Charles Kinbote, in Pale Fire (pp. 6-8). In America, Nabokov was forced to abandon his native Russian to write and translate in English (Boyd, 1991, pp. 5, 42; Boyd, 1993, p.6). However, born into ‘an old noble family’ and having ‘associations with England in Early childhood’, Nabokov wrote in English from an early age, therefore mixing up languages including Russian, French and English in his polyglot fictions (Boyd, 1993, pp.3, 420). In addition to Pale Fire, he is also famous for The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1941), Lolita (1955), and Ada, or Ardor: A Family Chronicle (1969).

Pale Fire is not limited to being read and analysed as a literary arabesque. The novel is very complex and provides an unlimited number of themes with an abundance of lenses for analysis. However, Pale Fire is constantly analysed via patterns that correlate with its themes. In his essay ‘Pale Fire: Poem and pattern’ (2010), Brian Boyd, states that ‘poetry … must always operate with patterns and indeed patterns of patterns. Even metaphor offers a new link between one more or less familiar pattern and others’ (2011, p.342). Boyd continues the discussion by comparing the poem to Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30 and the ‘alignment of its structural, logical and syntactical patterns’ (2011, p.343) and reiterates my argument by describing the pattern as a metaphorical function. He further identifies the pattern as a spiral which emerges from Nabokov’s quote about the ‘thetic arc’ (1999, p. 10, 233). Nonetheless, the arabesque pattern remains generally overlooked in critiques of the novel. To broaden this discussion, this paper explains the significant role of the arabesque motif as it is manifested throughout the novel and argues that the arabesque also contributes to further discoveries of the themes experienced by Nabokov’s characters by identifying the elements of the arabesque and illustrating how the arabesque has been transferred from a visual art to textual form. I will firstly outline a brief history of the development of the arabesque art form and how it became a writing style during the 19th century and then show how Pale Fire performs the literary arabesque.

The arabesque

The arabesque is an Islamic art form and an artistic representation of foliage that is derived from the idea of the vine scroll. The arabesque integrates different geometric shapes including circles and triangles to produce a single line that continuously circulates back onto itself. The arabesque is used by Muslims for decorative purposes on walls of Mosques as an aesthetic rendering of ‘geometric and vegetal forms, and even decoratively executed inscriptions and figural motifs’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.4). Its decorative motifs include regular repetitions, knots, interlacing, spirals, mirroring forms, continuity, unification of disparate elements, fragmentation and symmetry. The arabesque has also been examined through various perspectives including aesthetic, theological, philosophical and literary.

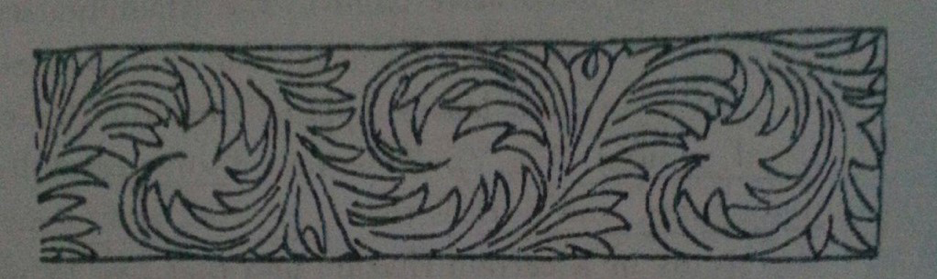

The Arabesque: Meaning and Transformation of an Ornament (1949) is the first book to document the history and development of the arabesque ‘from Late Antique times until the 16th century, when European art made its inroad on the Islamic world’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.1) and is written by the German historian and Islamic art researcher, Ernst Kühnel (1882-1964). Kühnel also traces the transformation of the arabesque into a literary style during the 19th century. Figure 1 shows a ‘cornice decorated with acanthus leaves … [in which] the foliage emanates and turns back regularly on itself’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.14). This aesthetic was used for decoration during the 5th century and the geometric structure of the arabesque is not yet developed at this stage. The artistic style of the acanthus continued to evolve over time and was used for decoration in architecture between the 7th and 9th centuries. During the 9th century, images of symmetrical patterns that followed a repetitive geometric structure began to emerge.

Figure 1. ‘Late Antique Cornice, 5th Century’ (Kühnel, 1976, 14).

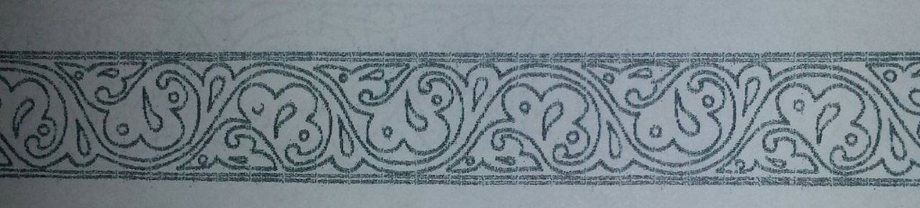

The earliest ornament which resembles an arabesque documented by Kühnel was during the Abbasid era, mid-9th century. Figure 2 shows how the design in Figure 1 transformed ‘from the freely flowing scroll … [to a pattern where] the whole regenerates itself imperceptibly in a symmetrical rhythm’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.16). The design is no longer free-flowing but is structured symmetrically and regulated by a specific path. This is also more visible in Figure 3 which shows the evolution and transformation of the design into a symmetrical composition.

Figure 2. ‘Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, end of 9th Century’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.16).

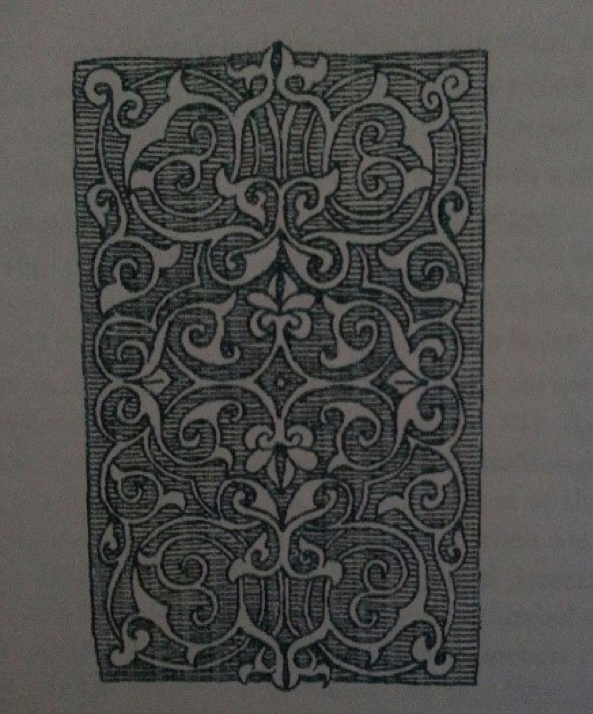

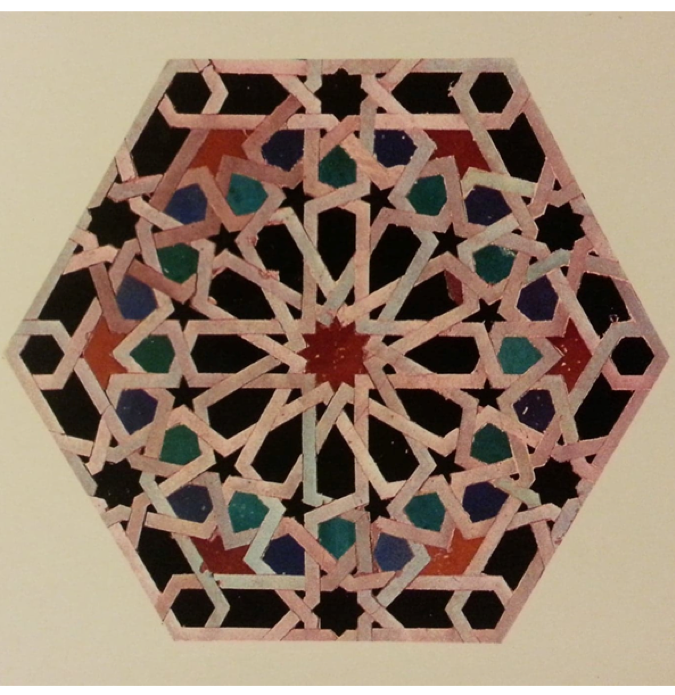

Figure 3 illustrates the manner in which an arabesque display is achieved: ‘starting from the centre, scrolls and bifurcated leaves spread out in various forms and in complete symmetry over the whole rectangle’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.24). This image shows a thoroughly developed arabesque decoration from the 11th century which illustrates a congruently repetitive embellishment.

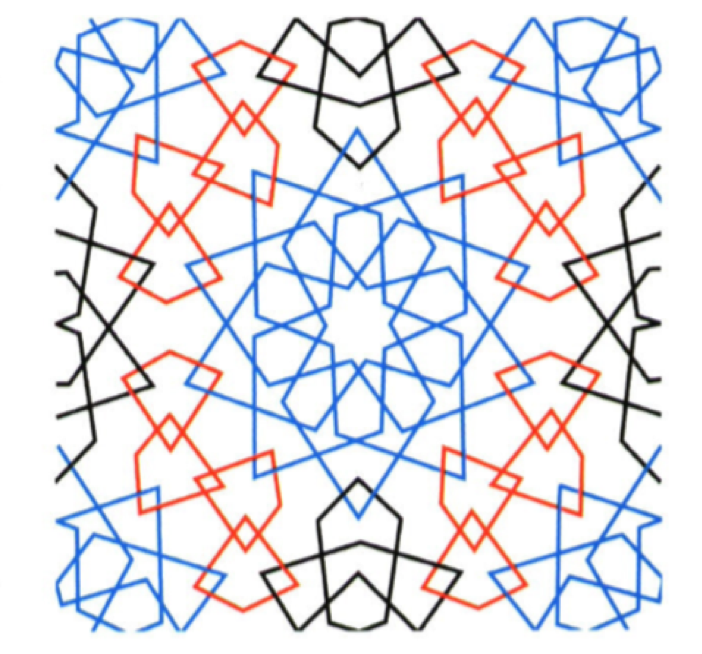

The arabesque can also adopt forms of kaleidoscopic and crystalline appearance via accumulated tessellation of shapes. The arabesque’s kaleidoscopic characterises therefore sends us further back into history, to the time of Euclid, since Islamic scholars derived the mathematical logic of the arabesque’s geometry from Euclid’s Elements of Geometry. They also studied Plato’s, Aristotle’s and Plotinus’s philosophies. However, this article focuses on Euclid as a major influence on Islamic art and the contribution of his geometric concepts to the arabesque because these geometric motifs are utilised in literary arabesques. Furthermore, geometric tessellation leads to kaleidoscopic effects and is also manifested in Nabokov’s Pale Fire which this paper also later illustrates.

Figure 3. ‘Wood Carving, Egypt, about 1000’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.24).

Geometry

Since the arabesque relies on perfect symmetry, equidistant lines and equilateral shapes are important. A circle is therefore the first shape drawn to start an arabesque, followed by inscribing other shapes such as squares, triangles and stars within, and emanating out from, the circle. This is because the circle allows for perfect symmetry as Plato argues in Timaeus,‘…and by leading [a worldly body] around [God] made it move in a circle, spinning uniformly around its own axis on the same spot… with every point on its surface equidistant from the centre, a body whole and complete’. (Plato, Lee, and Johansen, 2008, p.23). This argument appealed to Islamic scholars and Islamic artists. Seeing that the circle maintains an equal distance from the radius to the circumference the whole way around, it therefore allows for perfect symmetrical tessellation of equilateral shapes and equidistant lengths are important for symmetrical patterns. Hence, the circle had to be drawn first to begin the famously congruous arabesque that was to become the Islamic art form.

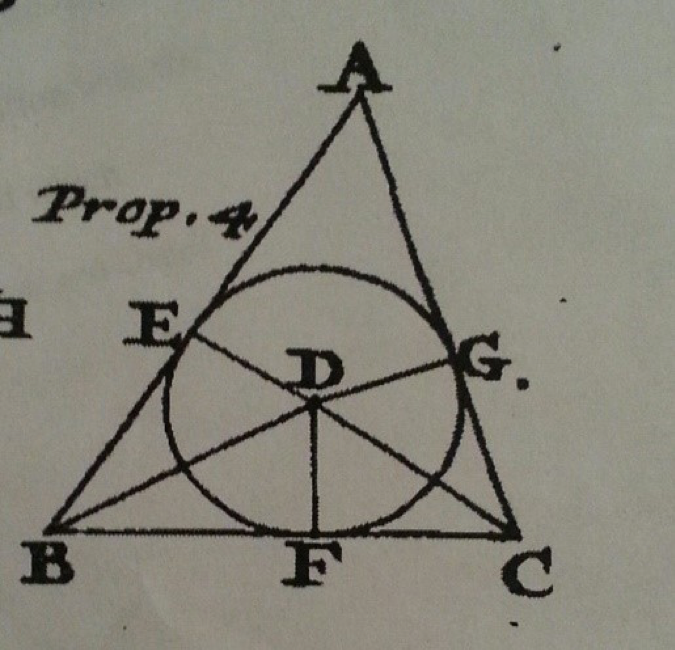

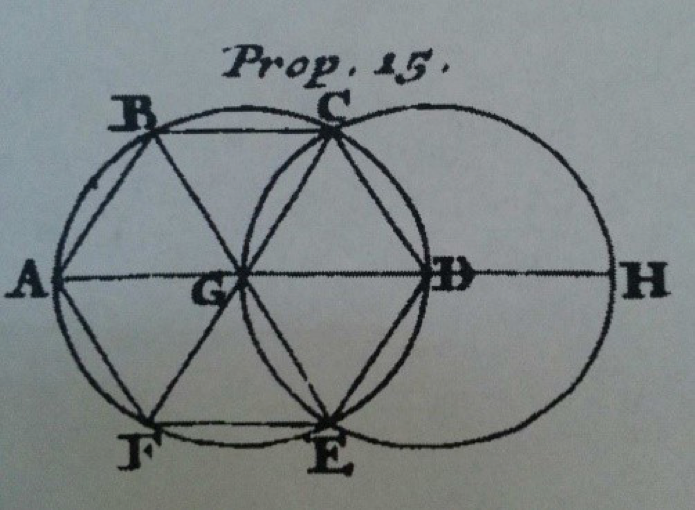

In contrast, if a circle was to be inscribed inside a triangle such as in Figure 4, not all lines will be of equal length such as lines DB and DF. Therefore, this method is not sufficient for an arabesque. Additionally, Islamic art prefers the use of a hexagon over the pentagon, for example, because ‘the side of the Hexagon is equal to the Semi-diameter of the Circle’ (Euclid, 1723, p.116). Notice how the precise symmetry in Euclid’s diagram (Figure 5) allows for a second circle, as well as a third circle, a fourth, and so on, to be drawn in order to keep the infinitely repetitive tessellating process. This is also important for an artwork that incorporates the motif of ‘no endings’ and continuity such as an arabesque.

The arabesque is therefore created by integrating different types of motifs to produce one complete unified ornament. The ornament is eventually brought together by the resulting interweaving line. If you follow the arabesque’s contour in Figure 6, you will notice that it is one single connected line which interweaves the design, returns to its starting point and continues to circulate endlessly. The beginning of the pattern therefore becomes the end and as a consequence, does not have a definite beginning, middle nor end.

Figure 4. Euclid’s ‘Proposition 4: To inscribe a Circle in a given Triangle’ (Euclid, 1723, p.116-117). Diagram accessible between pages 116-117 upon printing, but not electronic version.

Figure 5. Euclid’s ‘Proposition 15: To inscribe an equilateral and equiangular Hexagon in a given Circle’ (Euclid, 1723, 116-117).

Figure 6. An arabesque. This picture is on the cover on Keith Critchlov’s Islamic patterns: An analytical and cosmological approach (1976).

Some texts have been written in a specific style as to either mimic or evoke the arabesque, particularly its continuous and unending characteristic. In The Arabesque, Kühnel describes the way Goethe’s poem from ‘Unbounded’ in his West-East Divan (1814-1819) echoes ‘a single, continuous and apparently unending melody … bubbling up and then fading away in harmonies just as does [sic] the continuously branching of scrollwork’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.10). Goethe’s poem also reflects the way an arabesque ornament is capable of beginning where it ends, continuing where it starts, or beginning in the middle. Goethe’s poem provides the perfect description of an arabesque ornament because its beginning and ending are the same and the middle is at the start as well as at the end:

That you can make no ending makes you great;

That you have no beginning is your fate.

Your song turns round, a star-vault heaven frame;

Beginning, ending, evermore the same;

And the clear import of the middle part

Is present at the end, as at the start

(Goethe, Arnim & Bidney, 2020, p.23).

The poem describes a phenomenon that has no beginning, middle nor end. Nonetheless, its beginning, middle and end are also present and are all treated as one and the same (see Figure 6).

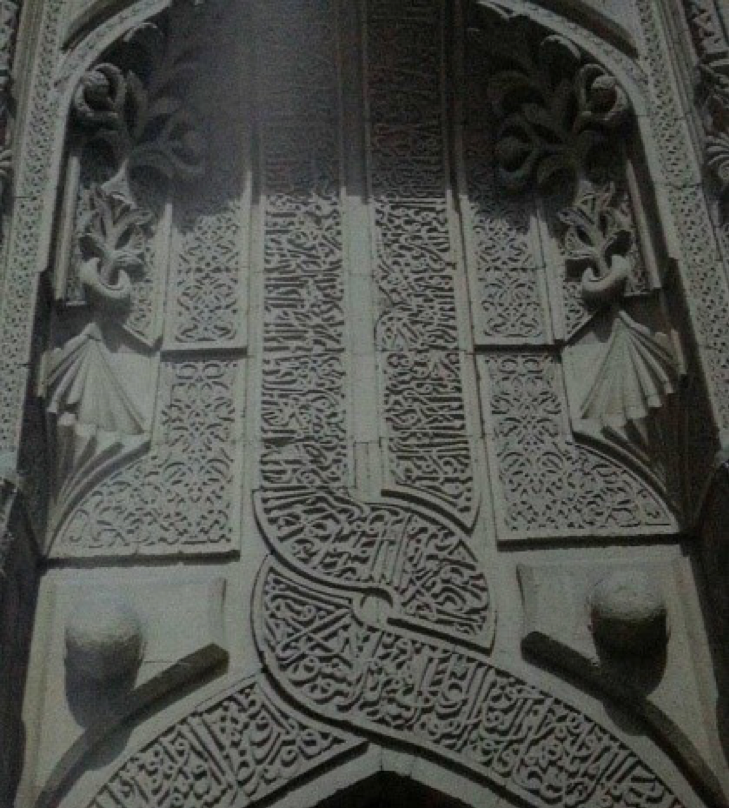

The continuous flow of arabesque floral designs is also reflected in the cursive and continuously flowing style of Arabic script, particularly calligraphy. From the mid-9th century onwards, literary art and calligraphy arose as a popular craft in the Arab world. Persian and Arabic words also began to appear as arabesques for aesthetic purposes. Artists also associated Arabic calligraphy with ‘difficult geometry’ due to its balance, measure and spacing as well as:

… music, for the scribe behaved like a musician, sometimes mixing the heavy movement with the light one … or by adding a beat or subtracting a beat’, which evokes the style of poetry (Irwin, 1997, p.180).

Calligraphic designs were placed on pottery, bowls, plates and walls of buildings (Figure 7). Mirror script, or Makus, was another fashionable and symmetrical style where ‘the left reflects the right’ and was used to decorate buildings (Irwin, 1997, p.179). Although Figure 7 shows how Arabic script is presented as an arabesque decoration, Kühnel states that the actual characters themselves were also presented in arabesque style: artists ‘treated the upper ends of tall straight letters or the curves of others as if they were ornaments and even gave them the appearance of arabesques’ (Kühnel, 1976, p.30). Hence, from a mere ornament to a decorative writing style, the arabesque’s elements of continuity, symmetry and ‘mirror images and upside-down repetitions’ eventually figuratively transferred into Arabic texts (Kühnel, 1976, p.7).

Figure 7. ‘Detail of entrance façade of the Ince Minare Madrasa at Konya, Turkey’, 13th Century

(Irwin, 1997, p.171).

The Arabian Nights is an example of a text that echoes the decorative Arabic script styles. Malcolm Lyons’ version of the 13th night of Arabian Nights tells the story of a king who is looking for a vizier in order to replace his previous vizier. The King makes acquaintance with an ape who is actually a wise man who had a spell cast on him, and also happens to be a skilled calligrapher. The ape decides to show the King his calligraphic skills and writes on a scroll in various scripted styles:

Open the inkwell of grandeur and of blessings;

Make generosity and liberality your ink.

When you are able, write down what is good;

This will be taken as your lineage and that of your pen

(Lyons, 2010, p.83).

The art of writing, which denotes a sense of ‘liberation’, is commemorated in Arabian Nights through meta-textual forms. Furthermore, images of calligraphic art on surfaces continue to be evoked such as when the narrative mentions ‘a lead tablet inscribed with names and talismans’ which evokes the image in Figure 7 (Lyons, 2010, p.91).

Stories of the Arabian Nights began to circulate among storytellers in Baghdad, Iraq, during the 9th and 10th centuries. These stories were never completed, and each story was left open-ended for the next story-teller to continue the narration on behalf of the heroine character, Queen Scheherazade. Not only did each story not end, but each short story began with ‘She CONTINUED …’ (Lyons, 2010). The arabesque’s motif of repetition is therefore apparent at the beginning of each anecdote.

During the 17th century, the French Orientalist, Antoinne Galland (1646-1716) travelled through the Middle East, studied Islamic culture and familiarised himself with the Arabic language. Galland translated the tales of the Arabian Nights into French in 1704 after a Syrian man, Hanna Diab, provided him with an oral version (Haddawy & Mahdi, 2008, p.xvi). These tales were later translated into English and European languages, including German and Russian (Irwin, 2010, p.x). As a child, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) had these stories read to him by his mother which influenced some of his writing and Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister is also an example of the literary arabesque (Mommsen, 2014, p.1-2).

Friedrich Schlegel (1772-1829) is considered as the father of the literary arabesque because he developed it into a higher and more complex form. Schlegel (1809) devoted an entire chapter to Goethe describing Goethe’s poetry as a high form of art. Schlegel also metaphorically referred to the romantic novel as ‘an arabesque’ which he also describes as a high form of art. Dialogue on poetry and literary aphorisms is comprised of five short sections that do not end with definite finales. For example, ‘Epochs of Literature’ ends with Schlegel’s character, Ludovico, saying, ‘What I have to offer and consider timely for a discussion is a’, and the section ends there, without Schlegel completing what Ludovico has to discuss, nor providing a full stop at the end, and continuing straight on to the next section (Schlegel, Behler, & Struc, 1968, p.80). The method by which Schlegel does not provide complete endings at the conclusion of his sections also mimics the indefinite end of an arabesque.

Influenced by Schlegel, Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852) wrote Arabesques (1835) and approximately 100 years later, Vladimir Nabokov wrote a fictional biography on the life of Nikolai Gogol called Nikolai Gogol (1944). Here, Nabokov places Gogol’s death at the beginning and ends the book with Gogol’s birth. Nabokov also places the last paragraph of Gogol’s Arabesques at the beginning of Nikolai Gogol as the preface. This reinforces the pattern of the arabesque which treats both beginning and ending as one and the same.

Pale Fire

Nabokov offers Pale Fire as a scholarly edition of the 999-line poem ‘Pale Fire’ written by Nabokov’s character, John Shade. It consists of four sections including the poem, Foreword, Commentary and Index. While ‘Pale Fire’ is written by Shade, the remaining three sections are written by Charles Kinbote who claims to be the rightful editor of the poem. However, the reader cannot really trust Kinbote’s translation of Shade’s poem (this becomes particularly evident in the section on Fragmented Wholeness later in this paper). This is because Kinbote believes himself to be an exiled king from an imaginary place called Zembla. Kinbote believes that his stories about Zembla, which he constantly narrates to Shade, are the source of inspiration to Shade’s poem. However, Shade’s poem mainly tells of his family life, particularly the death of his teenage daughter, Hazel, and his struggle with the topic of death and the failed attempt to discover answers about the afterlife.

The Commentary, which makes up most of the book, also consists of diverse stories told by Kinbote. These stories include Kinbote’s friendship with Shade, the escape of the Zemblan King Charles ‘The Beloved’ into exile, who the reader assumes to be Kinbote, and Gradus who is an assassin sent by the new Zemblan rulers to kill Kinbote. The way these diverse stories are interwoven to produce a single novel mimics the way different shapes and styles are integrated to construct a single arabesque decoration.

Phraseology

Additional conventions of a literary arabesque include phraseology, symmetry, reflections and mirroring forms, kaleidoscopic imagery, repetition, fragmented wholeness, continuity, circulation, and an unending structure and these are also evident in Pale Fire. The words and phrases that Nabokov uses in Pale Fire evoke the arabesque decoration. For example, Kühnel’s description of an arabesque is that it was ‘born from the idea of the leafy stem, but just as branches turn into unreal waves or spirals, so do leaves bifurcate and split’ (1976, p.5). Furthermore, observers of an arabesque need to find a point on the contour before they can begin tracing the pattern. Likewise, after constantly watching Shade from his window while Shade writes his poem in his yard, Kinbote eventually learns ‘exactly when and where to find the best points from which to follow the contours’ in order to get a glimpse of Shade while attempting to avoid ‘interference by framework or leaves’ (p.75). Additionally, Nabokov’s description of the roads also mimics the arabesque’s bifurcating stem:

After winding for about four miles in a general eastern direction through a beautifully sprayed and irrigated residential section with variously graded lawns sloping down on both sides, the highway bifurcates: one branch goes left to New Wye and its expectant airfield; the other continues to the campus (p.78).

These are only a few examples from Pale Fire where the description of events evoke some images and characteristics of the arabesque patterns.

Continuity

The arabesque’s continuity motif is also repeated in ‘Pale Fire’ through Shade’s endless journey of discovery in pursuit of the essence of the afterlife. Shade begins Canto Three by speaking of an ‘Institute of Preparation for the Hereafter’, the ‘I.P.H’, which invited him to give a lecture on death (p.44). The poem continues with Shade discussing various possibilities of the aftermath of death, including reincarnation, noting that he’s ‘ready to become a floweret / Or a fat fly, but never, to forget’ (p.44). This canto describes Shade’s longing to forget the death of his daughter, Hazel, as he writes to his wife, Sybil, ‘Later came minutes, hours, whole days at last, / When she’d be absent from our thoughts, so fast / Did life, the woolly caterpillar run’ (p.49). However, Shade is unable to forget since he dwells on the issue of death throughout the poem, questioning the possibilities of reincarnation one minute, and being ‘tossed/Into a boundless void’ the next, only to become nothing but a ghost and possibly have ‘a person circulate through’ him (p.45).

Recurring images of the hereafter continue to spiral from one possibility to another in the first half of Canto Three. In the second half of Canto Three, Shade talks about his journey which results in a void discovery and eternal hopelessness. His narration evokes the arabesque’s repetitive circulation. The following example also reflects the arrangements of diverse elements that make up the arabesque pattern and are interlinked by the arabesque’s single interweaving contour:

And blood-black nothingness began to spin

A system of cells interlinked within

Cells interlinked within cells interlinked

Within one stem. And dreadfully distinct

Against the dark, a tall white fountain played (p.50).

The interlinking system of cells to one stem is a dominant feature of the arabesque. It is an endless process of bifurcating stems and emanating contours that are all connected to one single interlinking stem.

Another example of an eternally continuing path is the ‘white fountain’ mentioned in the poem. This pattern parallels with the recursive path of the fountain’s flowing water. Following Hazel’s death, Shade also has a near-death experience which causes him to envision a fountain before he regains consciousness. He later believes to have found the answer to what exists in the afterlife when he reads in a magazine that Mrs Z. also ‘glimpsed a tall white fountain’ before she is brought back to life by a surgeon (p.52). Shade therefore sets off to find her and discover more. However, he is told there was a misprint in the magazine that is meant to read ‘Mountain, not fountain’ (p.53). Shade’s journey to find the connection he believed to have existed between his and Mrs Z.’s experiences ends in vain and he returns home with what he claims to be ‘Faint hope’ (p.54).

The arabesque’s continuity motif in Pale Fire is not limited to the notion of ‘infinity’ – the element of the ‘infinitely finite’ is also present. The fountain itself also presents a continuous pattern since the water travels endlessly along its own path, just as does the arabesque’s single contour. The course of the flowing water does not end – it continues where it starts and ends where it continues. This therefore reinforces the style of ‘Pale Fire’ as a literary arabesque, because continuity motifs with no definite beginnings or ends are included within the poem. Furthermore, no definite beginnings, middles and endings also conjure up themes of ‘uncertainty’. This is particularly portrayed by Shade’s denial of inevitable death that reflects his desire to be liberated from the eternal limits of death. As a pattern that infinitely travels freely around its own aesthetic realm, the arabesque remains interwoven and confined to the limits of its own finite path, hence, the element of the ‘infinitely finite’.

The ‘infinitely finite’ in literary arabesques is also associated with the concept of ‘ordered chaos’. Shade’s chaotic experience is harmonised by the fountain as a serene feature. Boglárka Kiss argues that:

… in its original form as an ornament the arabesque is based upon rhythmic repetitions and symmetries, where the corresponding parts mirror each other – and this harmonious design was supposed to calm the viewer’ (Kiss, Labudova, & Séllei, 2013, p.234).

The arabesque’s patterns, therefore, where symmetry and repetition are brought together in harmony, is intended to produce a serene effect. Nonetheless, in literary arabesques, the arabesque emphasises harmonised chaos and is utilised as a metaphorical literary device to represent the chaotic structure of events and life in general. Melissa Frazier refers to the motif of the literary arabesque, kunstchaos (ordered chaos),as the chaotic structure of order, or the ordering of chaos, and ‘a symmetrically and orderly constructed confusion’ (Frazier, 2000, p.26). Furthermore, in ‘the arabesque, confusion and chaos are arranged into an aesthetically organized and symmetrical totality’ (Jenness, 1995, p.62). Pale Fire simulates this notion of ‘ordered chaos’ when Shade returns home after searching for a white fountain and after discovering the he has been deceived by a misprint in a magazine (Fountain, rather than Mountain). He tells Sybil he is ‘convinced that I can grope / My way to some … Faint hope’ (p.54). Shade is disappointed that his journey to find the ‘white fountain’ ends with no result, yet he is determined that he can find a very small scintilla of hope. This scene is both chaotic and harmonising: it integrates the turmoil of Shade’s confusion as well as the calming movements of the fountain’s flowing water that produces a recursive pattern, mimicking the arabesque’s unified complexity and tranquillity.

Symmetry

The arabesque’s symmetry motif is reflected in Pale Fire’s symmetrical structure. ‘Pale Fire’ is comprised of four cantos and consists of 1000 lines. Hazel’s death occurs halfway through the poem at the end of canto two at line 500, therefore leaving Shade to oscillate from the midpoint to beginning and end, contemplating the death of his daughter and the topic of death in general.

The short (166 lines) Canto One, with all those amusing birds and parhelia, occupies thirteen cards. Canto Two, your favourite, and that shocking tour de force, Canto Three, are identical in length (334 lines) and cover twenty-seven cards each. Canto Four reverts to One in length and occupies again thirteen cards (Nabokov, 2011, p.11).

The time taken for Shade to write the poem is also symmetrical: three days to complete cantos one and four, and seven days to complete cantos two and three:

Canto One was begun in the small hours of July 2 and completed on July 4. He started the next canto on his birthday and finished it on July 11. Another week was devoted to canto Three. Canto Four was begun on July 19, and as already noted, the last third of its text (lines 949-999) is supplied by a corrected draft (Nabokov, 2011, p.12).

According to Kinbote, the first and last cantos have 166 lines, while the second and third consist of 334 lines, hence replicating the arabesque’s motif of symmetry.

Circulation

The infinite circulatory of the arabesque is mirrored in ‘Pale Fire’s’ repetition. Repetition is achieved by the poem’s similar beginning and end, akin to the arabesque. Although the poem contains 1000 lines, when we read it, the last canto only contains 165 lines, thereby leaving only 999 lines. In the last entry of the commentary to line 1000, Kinbote tells us that Line 1000 = Line 1 which mimics the arabesque’s motifs of circulation and continuity. The first and last four lines of the poem read as:

Line 1: I was the shadow of the waxwing slain

Line 2: By the false azure in the windowpane;

Line 3: I was the smudge of ashen fluff- and I

Line 4: Lived on, flew on, in the reflected sky.

[…]

Line 996: And through the flowing shade and ebbing light

Line 997: A man, unheedful of the butterfly-

Line 998: Some neighbour’s gardener, I guess- goes by

Line 999: Trundling an empty barrow up the lane (p.27, 60).

In other words, the poem does not contain 1000 lines. Rather, it contains 999 lines and canto four does not equal canto one which has 166 lines because the last canto has 165 lines. However, in his last commentary to ‘Line 1000’, Kinbote tells us that ‘Line 1000 = Line 1: I was the shadow of the waxwing slain’. In this case, the poem is read as follows:

Line 996: And through the flowing shade and ebbing light

Line 997: A man, unheedful of the butterfly-

Line 998: Some neighbour’s gardener, I guess- goes by

Line 999: Trundling an empty barrow up the lane.

Line 1000 = Line 1: I was the shadow of the waxwing slain.

Line 2: By the false azure in the windowpane;

Line 3: I was the smudge of ashen fluff- and I

Line4: Lived on, flew on, in the reflected sky.

[…] (p.27, 60).

The poem structurally returns to its beginning and continues on forever just as an arabesque continually repeats its course from beginning to end. Not only are these patterns identifiable in the poem, but they are also manifested throughout the whole novel. The arabesque’s infinite circulation and repetition is likewise identified in the Index section. Some references in the Index send the reader on a never-ending reading cycle. For example, the reference to ‘Crown Jewels’ creates the following pattern for the reader:

p.238: Crown Jewels, 130, 681; see Hiding Place.

p.239: Hiding place, potaynik (q.v.).

p.243: Potaynik, taynik (q.v.).

p.245: Taynik, Russ., secret place; see Crown Jewels (p.238, 239, 243, 245).

‘Crown Jewels’ leads to ‘Hiding place’ which leads to ‘potaynik’ and ‘Potaynik’ makes readers look up ‘taynik’ which says ‘Russ., secret place; see Crown Jewels’, requiring the reader to return to the first reference and then to circulate around the same group of words.

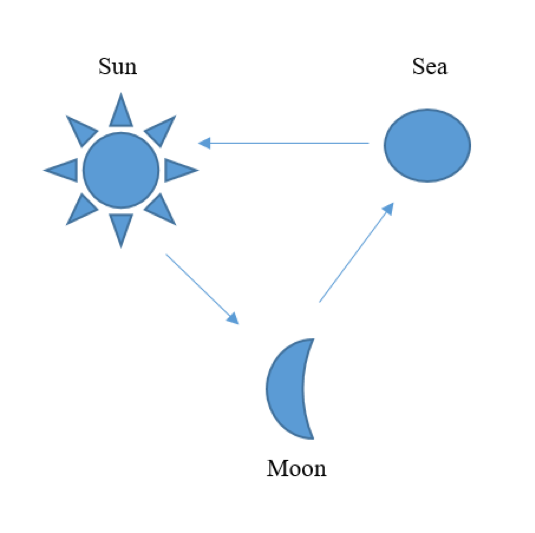

Another example of this pattern occurs in the Commentary when Kinbote recalls the passage from Timon of Athens where Timon provides examples of thievery that displays a boundless cycle. The passage from which Kinbote claims that Shade has borrowed from Shakespeare’s Timon is as follows:

The sun’s a thief, and with his great attraction

Robs the vast sea: the moon’s an arrant thief,

And her pale fire she snatches from the sun:

The sea’s a thief, whose liquid surge resolves

The moon into salt tears; the earth’s a thief,

That feeds and breeds by a composure stolen

From general excrement: each thing’s a thief: (Shakespeare, 2000, p.83).

Kinbote’s version of this passage, however, reads as:

The sun is a thief: she lures the sea

And robs it. The moon is a thief:

He steals his silvery light from the sun.

The sea is a thief: it dissolves the moon (p.68).

Figure 8. Endless circulation portrayed in both Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens and Nabokov’s Pale Fire.

Both citations portray boundless thievery and boundless circulation. This also points to the way Nabokov ‘stole’ the title ‘Pale Fire’ from Shakespeare, as writers ‘borrow’ (or give) ideas from (to) each other. In addition, the sun gives its light to the moon, the moon’s reflection lies in the sea, and the sea is gravitationally attracted to the sun. The pattern is an ever-continuing circulation without an ending.

Multiple reflections: Kaleidoscopic effects and multidirectional translation

Multiple reflections are also apparent in Pale Fire which illustrate the more complex motifs of the arabesque. Additionally, this style reinforces the importance of Euclid’s geometry because it is the arabesque’s symmetry which allows reflections to occur and subsequently result in refractions, followed by kaleidoscopic imagery. This effect is also achieved through tessellation (Figure 5). In other words, tessellation is a prominent motif of the arabesque; the repetition of reflection gives the arabesque its kaleidoscopic nature. These patterns are seen in Euclid’s illustration of symmetry and tessellation in Figure 5. The arabesque’s kaleidoscopic motifs can be seen in Pale Fire via the multiple reflections between characters, particularly Shade, Kinbote and Hazel. This can be seen in Figure 9 which illustrates how various repeated shapes linked by a central conjoining shape create this effect.

Figure 9. Complex geometric design by mirroring stone panels (Broug, 2007, p.96).

Eric Broug is an expert in Islamic geometric art as well as author and educator of arabesque designs and patterns. He analyses the image in Figure 9 as follows:

The design that has been created by mirroring one stone panel can itself again be mirrored, and that new design can then be mirrored again. This process can be repeated infinitely, and it is the essential attribute of Islamic geometric design (Broug, 2007, p.96-97).

Thus, the mirroring process can continue infinitely, creating multiple reflections.

In contrast to the postmodernist mise-en-abyme effect that creates ‘an endless succession of internal duplications’ between characters in novels, and which is infinitely projected in a single linear direction with the same image being reflected every second replica, my reading of multiple mirroring levels in Pale Fire causes both the image and the direction to change (Baldick, 2015, p.228). In his article, ‘The Viewer and the View’, David Walker argues that:

The dominant image of [Pale Fire] is the mirror, trapped in a prison of reflections, the characters are doomed to see, or think they see, everything as reflected image. Twins, doubles dualities, imitations abound. But these are no ordinary mirrors: all images are in some way altered or distorted (1967, p.205).

Walker gives an example of distorted mirrors from the first stanza of ‘Pale Fire’ when Shade provides reflections of opposing realities. Shade initially describes himself to be outside a window who ‘flew on in the reflected sky’, followed by duplicating himself ‘from the inside, too’ (p. 27). Shade continues to portray opposites when he writes the lines, ‘A dull dark white against the day’s pale white’ and ‘As the night unites the viewer and the view’ (p.27). Walker argues that this:

… suggests that the shadow (the illusory, half-real double) can penetrate the looking-glass, can transcend the boundaries of time and space, into the shadow world of illusion and art. The rest of the stanza demonstrates that on the other side of the glass there is also a reality reflected, a projected shadow world (Walker, 1967, p.205).

However, Walker’s argument suggests a linear succession of projecting images which reflects one set of opposites. In contrast, I argue that Pale Fire consists of multiple sets of opposites and that the reflections are penetrated by additional mirrors, thereby distorting the linear structure. This subsequently leads the reflections into different directions therefore distorting the initially distorted reflection. This argument is consistent with Meyer and Hoffman’s observations that ‘Pale Fire is structured on the idea that reality has an infinite succession of false bottoms’ (Meyer & Hoffman, 1997, p.197). Additionally, Pale Fire consists of ‘mirror image left-right reversal’ which adds additional directions to the reflections between characters, rather than an infinitely linear series of replicated images (Meyer & Hoffman, 1997, p.198). In Pale Fire, multidirectional reflection is shown through various levels of reflections between characters.

The literary arabesque uses the symmetrical form of the decoration, including its doubling motifs, to portray refractive relationships between fictional characters. Boglárka Kiss argues that the literary patterns of Sarah Waters’ Fingersmith (2002) can be analysed through ‘the concept of the arabesque – both in its original form as an ornament and in its reinterpretation as a literary device’ (Kiss, 2013, p.234). Kiss also argues that ‘postmodern imitation and reshaping of Victorian genres correspond to the various uses and aspects of the arabesque’ by portraying doubling characters in Fingersmith via the arabesque motifs of mirrors, repetitions and distortions. She says:

Doubling of characters reflects the primary function of the arabesque as an ornament, where the two parts of the pattern mirror each other, on the other hand the distortions between these pairings, the manipulation of the adopted genres, as well as the collision of fictional and real experiences are congruous with the Romantic re-appropriation of the arabesque (Kiss, 2013, p.234).

This analysis can be applied to the characters of Kinbote and Hazel who both feel different from the rest of society and who also incorporate mirror words in their speech.

Like the repetitions of mirrored patterns in Figure 9, Pale Fire also incorporates these motifs between Hazel and Kinbote. In the poem, Shade recalls Hazel’s use of ‘twisted words: pot, top / Spider, redips. And ‘powder’ was ‘red wop’’ (p.38). Kinbote uses similar mirror words when he attempts to persuade Sybil to reread ‘Proust’s rough masterpiece’, asking her to, ‘Please, dip, or redip, spider, into this book’ (p.131, 132). Pot and top are spelt backwards, making them mirror words. Adding an ‘s’ at the end of ‘redip’ makes ‘redips’ and ‘spider’ mirroring words with the conjoining ‘s’. Both Hazel and Kinbote reverse the order of spelling. Hence, the conjoining ‘s’ that links the words corresponds with the conjoining shape that links the mirrored patterns of the arabesque.

Furthermore, the conjoining shape also corresponds with Kinbote. Kinbote is the character who binds all other characters, just like the conjoining shapes of the mirroring forms of the arabesque, as well as the interweaving contour that unites the diverse motifs. Additionally, the reflection of a reflection also creates a new image akin to the effects in Figure 9, and to Kinbote’s imagination in Pale Fire. Kinbote observes that similarities exist between himself and Hazel when ‘discussing ‘mirror words’’ with Shade one day: ‘it is also true that Hazel Shade resembled me in some aspects’ (p.154). Kinbote is not only comparing Hazel to himself, but to all Zemblans since mirror words is the language of the Zemblans: ‘the tongue of the mirror’ (p.191). For example, the mirror-name for Shade’s killer, Jakob Gradus is Sudarg Bokaj. Assuming that the ‘j’ is silent and pronounced ‘y’, then the index reference, ‘Sudarg of Bokay’ implies Gradus, who is ‘a mirror maker of genius, the patron saint of Bokay in the mountains of Zembla’ (p.245). It is therefore traditional for Zemblans to appropriate mirror-words. Since Hazel also uses mirror-words, reflection between her and Kinbote projects onto all Zemblans. Therefore, multidirectional reflections occur when Hazel is reflected into a mirror and the image of Kinbote is shown one minute, Zemblans and Gradus the next. The image changes direction from one character to another, creating a multidirectional reflection; Kinbote and Hazel are mirroring characters and this reflection is repeated by exposing similarities between Hazel and other Zemblans through Kinbote as the conjoining character, just as the conjoining star in Figure 9 projects out to create new and different shapes in the pattern.

Multidirectional reflections within the novel/poem continue linearly, but also, somewhere along the way, the sequence shifts direction and an additional mirror is added from an alternative direction. As if to liberate the direction of reflection from its own convention, another dimension is added, thus fragmenting its linear order. Fragmentation can be seen in Pale Fire when Kinbote not only sees a reflection of himself in Hazel, but also sees Hazel as a reflection of all Zemblans (first mirror). Kinbote himself is Zemblan, and hence also reflects Zemblans (second mirror). Therefore, Hazel’s reflection projects from Kinbote onto all Zemblans (third mirror). Further distorted reflections occur when Kinbote also sees his Zembla in Shade’s poem (fourth mirror), only to discover that his Zembla is not there – his translation of the poem changes (Kinbote looks for an image for the fifth mirror), causing multidirectional reflection and multidirectional translation. Finally, this style of writing also reflects the transition from modernism to postmodernism which portrays ‘an abandonment of its determined quest for artistic coherence in a fragmented world’ (Baldick, 2015, p.288). Kinbote searches for an alternative reality through his own fictional Zemblan characters and Nabokov presents his postmodern novel through the arabesque writing style as an ideal method for constructing the notion of double characters, opposites and fragments.

Fragmented wholeness

Fragmented wholeness is another characteristic of the arabesque that is present in Pale Fire since various diverse objects and motifs unite to form one complete single ornament. Similarly, the poem ‘Pale Fire’ is constructed by uniting fragmented pieces of Shade’s original version of the poem after it has been distorted. In the Forward, Kinbote tells us that Shade’s poem consists of 80 index cards: ‘The manuscript, mostly a Fair Copy, from which the present text has been faithfully printed, consists of eighty medium sized index cards …’ (Nabokov, 2011, p.11). At the end of the novel, in the very last commentary entry to line 1000, Kinbote tells us that Shade’s poem consists of 92 index cards:

Some of my readers may laugh when they learn I fussily removed [Shade’s poem] from my black valise to an empty steel box in my landlord’s study and a few hours later took the manuscript out again, and for several days wore it, as it were, having distributed the ninety-two index cards about my person, twenty in the right hand pocket of my coat, as many in the left one, a batch of forty against my right nipple and the twelve precious ones with variants in my innermost left-breast pocket. I blessed my royal stars for having taught myself wife work, for I now sewed up all four pockets. Thus with cautious steps, among deceived enemies, I circulated, plated with poetry … (p.235).

This is the very reason why Kinbote can therefore not be trusted. Not only has Kinbote dismantled Shade’s poem by dividing up the batch of cards while hiding them in his pockets, but he has also recklessly compromised the exact number of cards that Shade used. Kinbote has either added, or subtracted, an extra twelve cards to, or from, Shade’s original copy. This emulates the process of unthreading an arabesque pattern. It is as if the arabesque is pulled apart and reconstructed back to a fragmented form of diverse shapes and elements. Kinbote’s additional twelve cards also suggests an extension to the poem in order to re-create or re-shape it, thus starting the pattern anew.

Conclusion: No endings

Like the arabesque that does not end, the poem ‘Pale Fire’, and the tales of the 1001 Arabian Nights that also never end, the novel Pale Fire also has no sense of ‘ending’ since the narrative on the last few pages does not ‘conclude’ the novel. Rather, it opens up possibilities for a ‘continued’ story by circulating between Kinbote’s past, present and imagined future, just as the arabesque circulates between beginning, middle and end.

In addition to the poem circulating back to its starting point, the story of Kinbote also circulates back to Kinbote’s past. In the final commentary, Kinbote imagines someone asking him, ‘what will you be doing with yourself, poor King, poor Kinbote? A gentle voice may enquire’ (p.235). Kinbote then reimagines his past by contemplating ‘sailing back’ to his ‘recovered kingdom’:

I may pander to the simple tastes of theatrical critics and cook up a stage play, an old fashioned Melodrama with three principals: a lunatic who intends to kill an imaginary king, another lunatic who imagines himself to be that king, and a distinguished old poet who stumbles by chance into the line of fire, and perishes in the clash between the two figments. Oh, I may do many things! History permitting, I may sail back to my recovered kingdom, and with a great sob greet the gray coastline and the gleam of a roof in the rain. I may huddle and groan in a madhouse. But whatever happens, wherever the scene is laid, somebody, somewhere, will quietly set out – somebody has already set out, somebody still rather far away is buying a ticket, is boarding a bus, a ship, a plane, has landed, is walking toward a million photographers, and presently he will ring at my door – a bigger, more respectable, more competent Gradus (p.235-236).

This passage, placed at the end of the novel in the last commentary note, alludes to Kinbote’s thinking as interweaving the past, present and future possibilities, all in the same single moment and place. This evokes the way the arabesque’s contour interweaves itself as it travels around the decoration, linking beginning, middle and end as one and the same. Kinbote then dismisses the past and returns to an imaginary ‘distant’ future where there might be a ‘more competent Gradus’ who will attempt to assassinate him. This might seem like Kinbote is moving on towards the future, but he is also returning to his past memories, since a ‘Gradus-like’ figure originates from his past Zemblan life. Kinbote’s imagination reverting to his distant past evokes the way the recursive arabesque circulates between beginning, middle and end. Kinbote’s imagination oscillates between history, present, future and back to distant pasts, just as the arabesque’s contour oscillates between beginning, middle and end. This reflects the perpetual arabesque which also seems to be suspended between time and space.

From a visual aesthetic to a textual style, the arabesque has travelled across various cultures and languages; Greek, Persian, Arabic, German, Russian and American, the latter three being mainly textual representation. Being a single decoration, it holds almost an unlimited number of patterning styles, making the arabesque a favourable aesthetic for writers and artists. This is particularly so for writer such as Nabokov who spent his life in migration and travels (Boyd, 1991, p.4). The arabesque’s contour that travels endlessly correlates with writer’s encounter which is illumined through their character’s experiences. While any reading of Pale Fire is not limited to a literary arabesque, nonetheless, treating it as a literary arabesque (that is, reading the novel with the arabesque motifs in mind) offers an alternative lens through which to engage with the novel. New themes and discussions emerge by examining the text as a literary arabesque and linking the various characteristics of the arabesque with their correlating threads. By identifying the arabesque’s motifs of symmetry, circulation, multiple reflection, continuity and no specific beginning, middle or endings, the literary arabesque is a very useful device through which to read Nabokov’s unique novel.

References:

Baldick, C., & Oxford Reference Online. (2015). The Oxford Dictionary of literary terms. (4th Ed.). Oxford quick reference.

Boyd, B. (1999). Nabokov’s Pale Fire: The magic of artistic discovery. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Boyd, B. (2011). Stalking Nabokov: Selected essays. New York: Columbia University Press.

Boyd, B. (1991). Vladimir Nabokov: The American years. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Boyd. B. (1993). Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian years. London: Vintage.

Broug, E. (2007). Contemplating Islamic Geometric Design. Islamica, (20), 94-98.

Critchlow, K. (1976). Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach. London: Thames and Hudson.

Euclid. (1723). Euclid’s Elements of Geometry. London.

Frazier, M. (2000). Frames of the imagination. New York: Peter Lang.

Goethe, J., Arnim, P., & Bidney, M. (2010). West-East divan. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Haddawy, H. & Mahdi, M. (2008). The Arabian Nights. London: WW Norton & Co Ltd.

Irwin, R. (1997). Islamic art. London: Laurence King Publishing.

Irwin, R. (2010). Introduction. In Lyons, M. (Trans.). The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights. Vol 2. (pp. ix-xviii). London: Penguin Books, 2010.

Jenness, R. (1995). Gogol’s aesthetics compared to major elements of German romanticism. New York: Peter Lang.

Kiss, B. (2013). The arabesques of presence and absence: Subversive narratives in Sarah Waters’s Fingersmith. In K. Labudova, & N. Séllei, (Eds.) (2013). Presences and absences: Transdisciplinary essays. Newcastle upon Tyne:Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Kühnel, E. (1976). The arabesque: Meaning and transformation of an ornament. Graz, Austria: Verlag Für Sammler.

Lyons, M. (2010). The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 nights Vol. 1. London: Penguin Books.

Meyer, P., and Hoffman, J. (1997). Infinite reflections in Nabokov’s Pale Fire: The Danish Connection (Hans Anderson and Isak Dinesen). Russian Literature,41(2), 197-221.

Mommsen, K. (2014). Goethe and The Poets of Arabia. Camden House, Boydell & Brewer. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt6wpb13.6

Nabokov, V. (1971). Nikolai Gogol. New York: New Directions Publishing.

Nabokov, V. (2011). Pale Fire. London: Penguin Books.

Plato, Lee, H., & Johansen, T. (2008). Timaeus and Critias. London: Penguin.

Schlegel, F., Behler, E., & Struc, R. (Eds.). (1968). Dialogue on poetry and literary aphorisms. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Shakespeare, W. (2000). Timon of Athens. New York: Penguin.

Walker, D. (1976). ‘The viewer and the view’: Chance and choice in Pale Fire. Studies in American Fiction, 4(2), 203-221.

About the author

Fatima Tefaili is a PhD student with the Writing and Society Research Centre, School of Humanities and Communication Arts at Western Sydney University. Her current project focuses on the literary arabesque and world literature. She completed a Master of Research degree in 2018, submitting a thesis titled ‘Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire: A Literary Arabesque’.