Illuminating distinctive cultural-linguistic practices in Palembangnese humour and directives in Indonesia

Susi Herti Afriani

Western Sydney University

Abstract

This paper explores distinctive cultural-linguistic practices in Palembangnese humour and directives. It reports on one aspect of a larger study that explores Palembangnese humour, culture, community, and institution in Indonesia. Palembangnese is a language spoken in Palembang city, South Sumatera, Indonesia that often includes ‘berkelakar’ (make a joke) in daily life. Kelakar is a noun in Palembangnese, interpreted as a joke and defined as words that are funny to make people laugh or happy. This paper argues that Palembangnese directives and humour are commonly misunderstood because non-Palembangnese people do not understand the cultural background and the context of the utterances. Palembangnese humour and the role of directives are founded in the combination of indigenous and Islamic cultures. This mixed-method study uses discourse analysis of electronic and print media in the city of Palembang, specifically Kelakar Bethook Palembangnese humour (KB data sets), Ceramah Islamic speeches (IS data sets) and Cerito Mang Juhai Uncle Juhai stories (JS data sets) to explore Palembangnese humour and directives. In doing so, it promotes wider awareness of how Palembangnese humour builds community and extends the limited research on the Palembang speech community.

Introduction

This research on Palembangnese directives was conceived when the writer was working as a linguistics lecturer in the State Islamic University, (UIN) Raden Fatah Palembang, Indonesia. As a native speaker of Palembangnese, the topic is close to my heart. To me, directives characterise Palembang-speaking people (Afriani, 2014; 2015b; 2019). Because directives ask someone to do something (Searle, 1969; 1976), they tend to be regarded as face-threatening speech acts (FTA) (Brown & Levinson, 1978). The speech acts of Palembang people may thus be perceived as rude to people who do not understand the culture. However, directive speech acts in Palembangnese culture have a role as humour, as shown in this paper. In addition, they also contribute to making Palembangnese humour distinctive. In Palembangnese, humour and directives are dominant features of typical conversations in daily life. Linguistically, one of the greatest challenges is understanding distinctive cultural-linguistic practices. In this research, my position as a cultural insider enabled a deeper methodological dimension to the research findings. This paper examines exemplars from each data genre in the data analysis.

To date, Palembangnese humour and directives have received limited attention in the research literature. Previous studies of Palembangnese linguistics have examined Palembangnese from different perspectives and analysis (for instances, Aliana, 1987; Amalia & Ramlan, 2002; Arif, Harifin, Usman, Ayub, & Ratnawati, 1981; Arifin, 1983a; 1983b; Dungcik, 2017; Muhidin, 2018; Oktovianny, 2004; Purnama, 2008; Susilowati, 2006; Tiani, 2018; Trisman, Amalia, & Susilawati, 2007). An area not yet researched is cultural-linguistic practices in humour and directives in Palembangnese. This paper responds to that gap to promote wider awareness of Palembangnese culture and humour and expand the literature on humour and directives.

In the city of Palembang, kelakar (jokes) is a longstanding tradition. Despite this, no research/er has discussed popular texts in Palembang that contain jokes, such as Kelakar Bethook Palembangnese humour (KB data sets), ceramah Islamic speech (IS data sets), and cerito Mang Juhai Uncle Juhai stories (JS data sets). These data are very popular and relevant to the Palembangnese speech community. A speech community may be understood in terms of linguistic anthropology and as a ‘community of practice’ (Wenger, 1998). In this paper, a speech community is defined as one that shares ‘values and attitudes about language use, varieties, and practice’ (Morgan, 2014, p. 1). The popular appeal of this data is evident through the large group of enthusiasts/followers, that continues to increase every year, and the wide audience and reader base from various work backgrounds, religions and ages (Wibowo, 2018). The relevance of this data is further supported by the popularity of the actors and speakers in the Palembangnese speech community. All the actors in the Kelakar Bethook, Palembangnese humour and the preachers in the Islamic speeches are considered celebrities in and beyond Palembang city. Here, celebrity means a media figure who has a prominent public role in expressing and legitimating the interests of the industry/public to entertain the audience (Turner, 2014).

Humour, because it is related to culture, can penetrate every area of life from daily interactions to politics, business, education and personal relationships (Lockyer & Pickering, 2005; Tsakona, 2017). Many anthropologists state the attitudes expressed in humour are culturally specific (Guidi, 2017). That is, what is considered funny by a speech community is dependent on the values, experiences, and habits they profess. Humour that is recognised by the speech community can thereby work to connect every individual in society by way of affirming what is considered funny and what values are strongly held. This paper provides a start in documenting previously under-researched cultural linguistic practices in Palembangnese humour and directives. The bigger study also suggests Palembangnese functions to maintain social relations among members of Palembang society. In doing so it helps to strengthen and maintain the tradition of joking in all circles in the Palembangnese speech community, and by documenting this tradition, it shows the distinctive cultural linguistic practices in Palembangnese humour and directives to young people in the city of Palembang.

Documenting Palembangnese is also important because, as one of many local languages in Indonesia, Palembangnese functions to distinguish Palembangnese identity. Studying how native speakers use this language in everyday life, and identifying distinctive cultural-linguistic practices in Palembangnese, helps provide references and resources for regional language teachers and Palembang cultural teachers as a source of learning material in schools or universities across generations. This will help strengthen understandings of Palembangnese and guard it against other foreign language attacks and extinction.

Palembang Malay Language

A brief introduction to Palembangnese

Palembang, on the island of Sumatra, is the oldest city in Indonesia (Hanafiah, 1989; Sustianingsih, Yati, & Iskandar, 2019). The language in Palembang is Baso Palembang [Palembangnese] which has two levels, namely Baso Palembang Alus [high register] and Baso Palembang Sari-Sari [daily language]. Baso Palembang Alus is used by elders at cultural, religious, and other rituals. Few people speak Baso Palembang Alus, and almost all people in Palembang use Baso Palembang Sari-Sari [daily language]. As a local language in Indonesia, Palembang Malay language has its own dialect and pronunciation. Palembang city has a strong sense of Malayan culture (Irsan, 2017) and values that inform everyday social and cultural aspects of life which is lived in accordance with the values of Islam. The map below shows Palembang Malay’s position in Indonesia (No 7). This research focuses on Baso Palembang Sari Sari, known as Palembangnese.

Map 1. The position of Palembang Malay in Indonesia (Adelaar, 2004, p. 2).

In general, the Palembang people consist of two groups of different social strata 1 . Although there are social strata differences, the actors in the three texts analysed in this paper do not switch strata according to the contexts. In other words, humour in the context of this research applies to all social strata in Palembang and can be understood by all groups.

Previous studies of Palembangnese

Several studies have reported on Palembangnese morphology, phonology, syntaxis, semantics and pragmatics (Afriani, 2015a; Amalia & Ramlan, 2002; Dungcik, 2017; Trisman et al., 2007). Baso Palembang Alus (BPA), as examined by Amalia and Ramlan (2002), emphasised the sound (phonology) and meaning of words (semantics). Somewhat different from Amalia and Ramlan (2002), Dungcik (2017), examined the Palembang language dictionary in terms of the structure and meaning of words (syntaxis and semantics). Trisman et al. (2007) examined spelling and made guidelines to better understand how Palembangnese was written. Afriani (2015b) investigated English directives of Palembangnese native speakers using pragmatic analysis.

To date, no research in Palembang represents both spoken and written Palembangnese, nor has any research investigated Palembangnese humour and directives at the level of discourse analysis. This paper contributes to this gap by analysing humour and directives involving the following three texts: (1) Kelakar Bethook that represents conversations among close-friends, or a husband and a wife, or family members in informal settings; (2) ceramah [Islamic speeches] among religious teachers and audiences in formal / informal settings; and (3) cerito Mang Juhai [Uncle Juhai stories] that represent conversations among close friends, a husband and a wife, and/or community and leaders in informal settings.

Research Design

This mixed-methods research analysed verbal and written texts using discourse analysis (DA) and interpreted them using Partington (2006) affective-face theory. Partington (2006) draws on Brown and Levinson’s (1978) theory of politeness to explain why disturbances in authentic discourse cause laughter. The concept of politeness and face arises from the laughter that occurs, for example, after a small violation in a conversation or situation involving the listener (audience). The concept of face is related to politeness because face is a concept of self-esteem (Brown & Levinson, 1978) and laughter can signal a participant being part of the group (Partington, 2006). The face is defined as the public self-image that everyone has (Brown & Levinson, 1978), which is considered to have sociological significance.

Affective-face theory is used to explain the concept of face between Palembangnese speakers and listeners (audience) or the speech community as it occurs in the three data sets. Through these data sets, this paper examines if Palembang people have more competence faces (formality) or affective faces (informality). A competence face is a face that is able to ensure the speaker is capable and authoritative, while an affective face is a pleasant face, not threatening, and acceptable by people. Anthropologically, the desire to appear without threats is an attempt to enter the group (Partington, 2006).

Methodology

Data Collection

Data for this study were collected through media, both electronic (Kelakar Bethook Palembangnese humour and Islamic speech data) and print media (Uncle Juhai stories). The data from Kelakar Bethook and Islamic speeches were sourced online. In total, the data consisted of 30 popular texts in Palembangnese: 10 Kelakar Bethook Palembangnese humour produced by PALTv (Palembangnese television) and downloaded from YouTube; 10 ceramah Islamic speeches, and 10 cerito Mang Juhai Uncle Juhai stories Palembangpos newspaper. All were transcribed, translated into English and analysed. The table below details each data set.

|

Title (30 popular data of Palembangnese): Kelakar Bethook Palembangnese Humour, Ceramah Islamic speech and cerito Mang Juhai (Uncle Juhai stories) |

Number of words in Palembangnese transcriptions |

Number of words after data notations and cultural explanations |

|

|

||

|

Transcripts of Kelakar Bethook Palembangnese humour (KB data sets) |

||

|

Video 1: Humorous of Palembangnese people, guessing |

653 words |

3701 words |

|

Video 2: It is because the stupid groom, so Yai Najib stops to be Ketib (Ketib is a term use for wedding officiant who arranges and declares the marriage) |

459 words |

2873 words |

|

Video 3: Yai Najib and Cek Eka act deaf. |

892 words |

4184 words |

|

Video 4: Chinese lucky cat of Cece Maria’s customer and Yai Najib |

680 words |

3386 words |

|

Video 5: Cek Daus breaks the police’s rules. |

484 words |

2468 words |

|

Video 6: Let God do his job for Cek Mawar and Cek Popi |

512 words |

2340 words |

|

Video 7: Cek Maria tastes fried food |

654 words |

3587 words |

|

Video 8: Yai Najib is failed to be romantic |

941 words |

4133 words |

|

Video 9: Miko is looking for wife (i.e. Mawar) |

768 words |

3851 words |

|

Video 10: Dentist at Studio 42, Ayu, Maria, Yai, Izal, and Ari

|

998 words |

4802 words |

|

Transcripts of Ceramah Islamic speech (IS data sets) |

||

|

Islamic Speech 1: Allah, the All seeing |

2370 words |

7280 words |

|

Islamic Speech 2: Welcoming Ramadhan, the Holy month |

3780 words |

9342 words |

|

Islamic Speech 3: Demons in Ramadhan |

610 words |

2034 words |

|

Islamic Speech 4: Five important things in Ramadhan |

469 words |

1634 words |

|

Islamic Speech 5: Human’s life purposes |

918 words |

2874 words |

|

Islamic Speech 6: Types of Jinn |

1353 words |

3792 words |

|

Islamic Speech 7: Severe punishment for those who commit disobedience |

559 words

|

2338 words |

|

Islamic Speech 8: Being the people of Muhammad by doing his sunnah |

1712 words |

5610 words |

|

Islamic Speech 9: The wisdom of Muharram |

2894 words |

8601 words |

|

Islamic Speech 10: Preparation of the hereafter

|

3558 words |

10140 words |

|

Transcripts of Cerito Mang Juhai Uncle Juhai stories (JS data sets) |

|

|

|

Uncle Juhai story 1: The Night Patrol |

291 words |

1418 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 2: Wonder Drug |

274 words |

843 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 3: Being Patient |

472 words |

2118 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 4: Lots of Wishes |

449 words |

1992 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 5: The Phone Credit Debt |

304 words |

1327 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 6: The sick son |

441 words |

1653 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 7: Incomplete Answer |

349 words |

1367 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 8: Girly Healer |

319 words |

1517 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 9: Four time extra |

506 words |

2309 words |

|

Uncle Juhai story 10: Pempek Dos (Palembang style fish cake without fish) |

467 words |

1896 words |

Table 1. Data in number of words

Analysis

A mixed-method approach using DA was used to analyse the data. Discourse analysis seeks to explain the content of a manuscript and identify themes/issues in the manuscript (Hamad, 2007). Because understanding humour is a complex process, discourse analysis is considered an appropriate approach to understanding the ambiguity and complexity of the text. As Schnurr and Plester (2017, p. 310) observed, ‘the complexity and ambiguity … make humour such an interesting topic for discourse analysis enquiry’.

Discourse analysis enabled the researcher to: (1) identify the distinctiveness of Palembangnese humour and directives in relation to politeness (Partington, 2006); (2) include narrative description and interpretations; (3) recognise the researcher’s position within the study (Creswell, 2018, p. 44), as a resident of Palembang for more than 30 years.

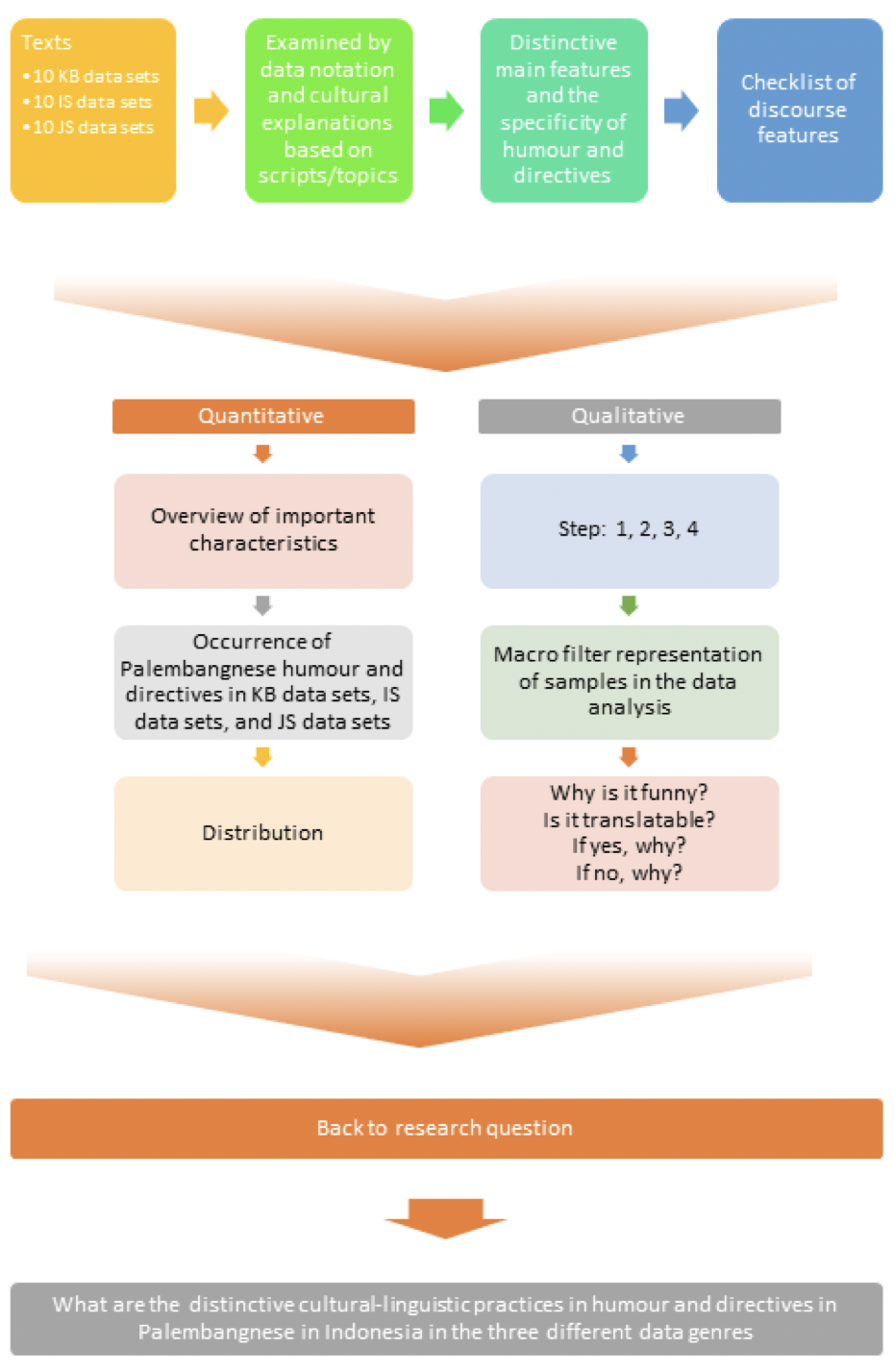

The data analysis was inductive, continuous, and sustained and looked for patterns of DA features in Palembangnese. In addition, an interpretative frame (macro analysis) was applied to each text as an analytical tool, as depicted in Figure 1. This tool helped identify instances of humour and directives.

Figure 1. Steps of analysis for the present study

Figure 1 shows the analysis process of the 30 data sets. After each script was examined, the distinctive features and specificity of humour and directives were summarised. ‘Script is taken as a neutral term among the various proposals (e.g., frame, schema, daemon, etc.) and thus does not have exactly the common meaning of the term A1. A script is defined as a complex of information associated with a lexical item’ (Attardo, 2001, p. 53).

Prior to analysis, each text was also reviewed for characteristics of its discourse features: conversation, politeness, topic, power, variables, face needs, aspects of styles, context, and aspects. The quantitative data analysis indicated the number of occurrences of important characteristics of each genre data, the number of appearances of humour and directives with the same theme and the distribution of humour and directives. The qualitative analysis explained the nuances of Palembang humour and directives; if the example was easily translated into English; and if the humour and the directive was funny for the Palembang audience.

Findings

Overall, the findings show the type of humour and directives in Palembangnese in the three genres of data. Table 2 makes explicit the forms of humour and directives evident in the data.

| Datasets |

Media |

Types of Palembangnese humour and directives |

|

KB1-KB10 |

KB data was produced by PALTV (Palembang television) and distributed to YouTube |

Humour: A comic moment, ‘lie’ humour, ‘misunderstanding’ humour, a contextual humour, a non-performative utterance (a comedy of error-humour), excessive praise humour, fantasy humour, FTA and self-elevating humour, irony and humour, kelakar (jokes), joke and self-elevating humour, Palembangnese culture exaggeration, pretend to be stupid, pun (play of words), riddle and jokes, satire, self-disparaging humour, self-elevating humour, solidarity laughter, and teasing. Directives: Commands, requests, advice. |

|

IS1-IS10 |

IS data was produced by Palembang television and radio and distributed to YouTube |

Humour: Jokes (kelakar), jokes (satire), jokes (teasing), jokes (pranks), jokes (sexual), jokes (woman’s characters), jokes (pregnancy), jokes (women’s body), jokes (angel’s characteristics), jokes (irony), jokes (death), jokes (social problem), jokes (human’s character), jokes (understanding Islam), jokes (pun), Pun and abbreviation. Directives: Advice, commands, requests. |

|

JS1-JS10 |

JS data was produced by Palembangpos newspaper and distributed locally (Palembang city) and online |

Humour: Jokes (kelakar) and teasing Directives: Requests, suggestions, advice, commands. |

Table 2. Palembangnese media and the overall types of Palembangnese humour and directives

Table 2 above illustrates that kelakar [jokes] and rich and varied directives are present in each genre. This suggests humour is an effective way to ask someone to do something in the city of Palembang. Specifically, humour and directives are able to change the community according to the agenda in each text. Even though the media is different, and the genre is different, the three data sets are performing humour combined with directives, which are consistent with all social norms. This is an objective and measurable reality. Therefore, these three text data sets not only function as samples of humorous texts and as cultural artefact-texts. In addition to showing the emergence in detail of the types of humour and directives in Palembangnese, Table 2 also shows that although the three genres data come from different sources, they actually have a common goal of building relationships, enhancing interactions and building community in the city of Palembang through humour.

Discussion

This section illustrates the nuances of Palembangnese humour and directives. It consists of three main sections: the descriptive analysis of one sample of texts from KB data sets; a discussion of an Islamic speech text, and a discussion of one of the Uncle Juhai stories text. Each data set shows individual characteristics, as discussed below.

Kelakar Bethook Palembangnese Humour

The Kelakar Bethook Palembangnese humour data sets show that humour and directive are funny and complex, as they can translate/transfer and not translate/transfer into English. To understand humour and directives that cannot be captured through text translation, each text needs a reference and/or context and cultural explanation. Other typical features include the complexity of the text and the FTA that functions as humour, the concept of face/teasing and solidarity. This solidarity is demonstrated through laughter. The representative example of KB analysis is taken from Video 2, entitled ‘It is because of the stupid groom, so Yai Najib stops to be Ketib [headmen]’ (hereafter referred as KB2). Ketib is a term used for the wedding officiant who arranges and declares the marriage, which was published on 9 December 2016 in the conversation between a headman and a bridegroom and his family.

In Palembangnese culture, the speech situation in Example 1 below (1a-1h), consists of the following parameters: Ketib [headman] has power that is respected in Malay culture and in marriage situations. This is because the Ketib task is considered important in the success of the marriage contract process. Hence, Ketib has a high social power, the social distance of Ketib, and the bride and groom’s family are not too familiar, and the weight of the conversation is quite high. As with other wedding ceremonies, the marriage led by the Ketib in Palembangnese cultureis full of conditions of happiness and related to Islamic religion. This is very well organised and in accordance with Islamic law, so there are many strict words from all speech acts.

| (1)a |

KB2- Script 9 |

: |

Ketib: ‘Naa…bukan itu maksud aku tu’ (Naa…that is not what I mean)

|

|

(b) |

KB2- Script 10 |

: |

Groom: ‘Naa…bukan itu maksud aku tu’ (Naa…that is not what I mean)

|

|

(c) |

KB2- Script 11 |

: |

Ketib: ‘Ai…dem’ (expression-while scratching his head)

|

|

(d) |

KB2- Script 12 |

: |

Groom: ‘Ai…dem’ (expression-while scratching his head)

|

|

(e) |

KB2- Script 13 |

: |

Ketib: ‘Kau tu!’ (You!)

|

|

(f) |

KB2- Script 14 |

: |

Groom: ‘Kau tu!’ (You)

|

|

(g) |

KB2- Script 15 |

: |

Ketib: ‘Pelok’i omongan aku’ (Follow my speech)

|

|

(h) |

KB2- Script 16 |

: |

Groom: ‘Pelok’i omongan aku’ (Follow my speech) |

Example 1: A conversation between Ketib and Groom in a marriage situation.

In this paper, I analyse examples (1a) to (1h) using the speech act theory (Searle, 1969) and affective face (Partington, 2006). The basic text of KB2 is that there are performative speech acts in a marriage situation, with conditions of religious celebrant happiness (socially organised and with very strict words from all speech acts). All participants know the rules and are active in the performance, with true support and speech. Script collisions (a type of error comedy) are among a series of mandated speech. There are some formal and ritual ceremonial utterances and ways in which all ceremonies are tampered with (and considered null and void by law) by repeating every utterance that ketib [headmen] makes, including non-verbally, by the groom, as shown in examples (1b), (1d), (1f) and (1h).

The utterance is a complete FTA and anger, which understandably, sees its own status and ceremonial role, and is made into a comic moment or a comedy error. The comedy of error is defined as ‘a comedy in which the plot develops through, and humour derives from, a series of misunderstandings, mistaken identities, etc’ (Oxford English Dictionary, 2019, p. para. 1). In addition, the central humorous element in the KB2 text is that the groom repeats all the non-performative utterances, including the ‘ahem’. This sets up a collision between the very serious, formal, ritualised language and non-performative utterances which precede and lie outside the actual ceremony. In short, the examples (1) of the repetition above are translatable, even if they are nonsense or sound symbolic, but the difficulty of translating makes them distinctive.

Ceramah [Islamic Speech]

In the ceramah [Islamic speech] data sets, the humour tends to be more persuasive and contains advice and directives that are accepted, appreciated, and enjoyed by a wider audience. The following example is a narrative description and interpretation of IS1 data. This IS1 is a text entitled Allah maha melihat [Allah the all-seeing]. This lecture was delivered at the grand assembly of remembrance that was attended by all strata of society, including the Governor of South Sumatra, the religious scholars and the community (which I further refer to as ‘audiences’). In accordance with the committee of the event, the main theme in this lecture was about remembrance. Recitation in Islam can be defined as one of the methods used by Sufi scholars to revive the heart from its death. This is caused by a heart that does not remember the majesty of Allah SWT and will be considered dead by the Sufis. Dzikr activity is then considered to be able to awaken a person (Muslim) to the existence of his true God. After opening the mirror with greetings, and typical greetings from Palembang, Kyai H. Taufik Hasnuri (the speaker) tries to open lectures with serious topics (key-content of speech) to strategic moves (humour).

The main discourse feature found in this IS1 is that the topic is formal, the speaker has control over the audience and the negotiated interactions and listeners show they are ‘communicating agreement’ (Partington, 2006). ‘Face’ also occurs in this ceramah situation and both participants express their solidarity. Although the message was delivered in Palembangnese, the content and supporting evidence still refer to the Al Qur’an and sunnah in Islamic religion.

| 2 |

IS1-Topic 5 |

: |

‘Bulan puasa alhamdulillah yang memberi kurma, yang memberi gula, yang memberi sirup banyak, yang itu tidak saya pikirkan yang ini tidak pernah saya pikirkan, yang saya pikirkan tidak dikasih… haaa…haaa…haa (jamaah tertawa)’ [When Ramadan, thanks to Allah. Many people gave date palms, sugar, and a lot of bottles of syrup. I don’t mind with all of them. What matters to me is people did not give any of them to me (audience laughing). That thing becomes a matter, indeed. Where are others now? Lives in Indonesia are very hard every day. The functionaries such as a governor and a president should pay attention to their people, easing suffering as they have now].

|

Example 2: A piece of Kyai H. Ahmad Taufik Hasnuri’s (Ustadz Taufik) lecture titled ‘Allah, the all-seeing’

Example 2 above is about the blessed month of Ramadan. Through this topic, the speaker tries to make a joke that Ramadan is a glorious month. This was said because this lecture was delivered in the month of Ramadan. Basically, the lecturer conveys the concept of sharing that is very appropriate to be carried out in the month of Ramadan. Interestingly, he gave this advice in a very funny way. He said that he himself ‘must’ also get the distribution (prize). This is a kelakar (joke) and this is distinctive because this is a community-minded context and not individual. However, this joke was carried out to convey a serious matter, namely lecturers entering the area criticizing government policies (fair leaders), which resulted in rampant corruption and resulted in many poor people in Indonesia. Ustadz Taufik tried to connect humour in this manner with the character of a leader who did not remember God. The leader who commits corruption for him is a leader who is not afraid of death. Another example of the jokes is shown in Example 3 below.

|

3 (a)

(b) |

IS1-Topic 7 |

: |

‘Kaya menunggu nasib, kaya menunggu takdir, miskin sudah keturunan haa…haa… (jamaah tertawa)’ […those who are less-lucky mostly come to the mosque (audience laughing). Well, time has been already five minutes, time is up (audience laughing)]’.

|

Example 3: The continuation of Ustadz Taufik’s lecture in the title ‘Allah, the all-seeing’

On the seventh topic (example 3b), the speaker uses directive speech acts. Lecturers remind audiences of the concept of death. Every human that lives will surely die. In essence, the speaker reminds that death does not recognise social status, wealth and position. However, what is interesting is that although this is a form of advice, lecturers still insert humour. This can be seen in the phrase (example 3a) ‘the poor come here diligently’ haaa … haa .. (pilgrims/audience laugh) that a lot of money rarely comes ‘for what? … who?’ haaa …. haaaa (pilgrims/audience laugh). This phrase means that only the poor come to the mosque and/or majelis taklim [Muslim prayer group] diligently, whereas the rich do not like to come. This is an example of a Palembangnese joke. In other words, the speech (3a) was funny because the speaker ‘insinuated’ that only the poor were diligent in coming, while the rich (who owned the property) did not want to come to the mosque because they did not have any interest in doing so. This joke is funny, and more widely translatable or applicable, because it alludes to the unique behaviour or character of every human being. Here, the lecturer only wants to remind that the status of rich-poor is the same thing in the eyes of Allah SWT (God), and the rich and poor have the same obligation to remember Allah SWT. In this example, what the lecturer wants to say is that both the rich and the poor have an obligation to attend the Tabligh akbar program, as an attempt to show their efforts to know the knowledge of Allah (the relationship to Allah SWT), and also to fulfill the duty of Muslim friendship.

In summary, Examples 2 and 3 (a) above demonstrate kelakar [jokes], known as typical Palembang. Kelakar is a form of joke and berkelakar [to make joke] is a habit of the speech community in the city of Palembang. Besides being an easy way for the speaker to ask the listener to do something, a joke also appears in tandem with the directive so as to form a distinctive pattern.

This paper through ceramah [Islamic speech] (IS1 data) is the first research on Islamic lecture data from humour analysis and shows one side of Malay civilisation in Palembang. Specifically, this paper is the first study examining humour in Palembang Malay Islamic lectures. Palembang Malay research through humour and directive examination shows how the form of speech is able to adapt to the diversity of the audience (today). Therefore, this paper is able to show that the speaker has the ability of an intelligent communication strategy to the public. The concept of Islam is considered very serious but is packaged in an attractive and moderate manner, so that it is easily accepted by all social statuses.

Cerito Mang Juhai [Uncle Juhai stories]

In Cerito Mang Juhai [Uncle Juhai stories], there is an implicit assent to humorous events. As JS data sets are written texts and textual humour, the humour is implicit, even though explicit laughing signals are found in the post-comment. The terms of textual humour and humorous text are interchangeable. Attardo (2001, p. 33) argues that technically, the definition should be even more complex:

A humorous text is a text whose perlocutionary goal is the recognition on the part of its intended audience, which may or may not be the actual audience of the utterance (s) of which the text is composed of the intention of the speaker or of the hearer of the text to have said text be perceived as funny. Note that the humorous ‘intention’ may be in the eyes of the beholder, so to speak, this is necessary to account for ‘involuntary’ humour. The actual nature of the hearer’s ‘intention’ is problematic and requires further work.

Although the audience is not present in the textual humour, the nuances of humour and the role of directives occur in Cerito Mang Juhai [Uncle Juhai stories] data sets. Based on the type and its characteristics, JS data sets humour is also distinctive in its topicality, referentiality and collocational-cultural norms. The following example is taken as one of the Uncle Juhai story representation of data sets from JS1. This story illustrates the situation of Mang [uncle] Juhai (a main character) who has a conversation with his friend, called Mang Oding. In this situational context, both of them are using casual and informal language and functions of solidarity. The topic is delivered through negotiated interaction. The way the actors speak reflects and perpetuates Palembangnese cultural expectations and power positions. Face threatening acts (FTAs) occur through directive action. However, there is no indication of losing face, since the conversation is held in a private setting and the characters are very familiar with each other.

Example 4 below provides a script of Palembangnese jokes. In Palembangnese culture, Mang Juhai’s speech to his friend Mang Oding and/or Ding is called ‘besak kelakar’. This script is called besak kelakar [a big joke] because Mang Juhai’s utterance is a long, shallow and meaningless utterance that has no strong proportional content. In other words, ‘besak kelakar’ can thus be interpreted as a speech that has a hyperbolic style, delivered in the form of hoax, or nonsensical frame. While Mang Juhai’s speech takes the form of a serious speech, it has no informational content, so the speech becomes funny. Hence, the topicality is seen in the contents of the text where the reader can understand the humour delivered. This is because the reader already has a reference to the concept of besak kelakar in Palembang culture.

| (4) |

JS1-Script 5 |

Mang Juhai: ‘Nah mak itulah Ding. Dengan kito aktif ronda malam, paling idak, kagek ado apo-apo di kampong, kito pacak tau. Kemudian, daripado katek gawe di rumah, dan mato nerawang kemano-mano kareno tidok dak galak, mendingan kito ngamanke kampung’ [Uncle Juhai: Nah, that way Ding. By us being active in the night patrol, at least, later when something comes out in our village, we should know. So rather than doing nothing and wandering around with your insomnia at home, it is better for us to guard our village].

|

Example 4: One form of the main character’s utterances in the title ronda malam ‘the night patrol’.

Example 4 above is the opening script of Mang Juhai’s utterance. The script is funny because both of Mang Juhai and Mang Oding continue to talk about the intention to protect the kampung [village], without moving to make a concrete start. This can be defined as fiasco. Partington (2006, p. 67) argues that difference between a joke and a lie is that telling a joke is an act of cooperation, while telling a lie is a deception. However, both these kelakar [joke-telling and lies] in the context of Palembangnese have ‘fiction and deception involved in both, but only in one is the deception meant to discovered’ (Partington, 2006, p. 67). Even though the audience is not present in Example 4, the nuances of cuteness can be captured. This is reasonable as we know there is assent/affiliation, since the text is popular. If we know that the text is popular then we know that people approve (are laughing) at the humour. Therefore, this text is considered textual humour.

McMillan (2000, p. 5) argues that:

textual humour can arise when authors or illustrators play with readers’ expectations. Because a representation becomes comic when it defines the way in which readers usually think, comic when it extends commonly held logic, comic humour can be useful resource in challenging habits of thought.

Similar to KB and IS data sets, JS speech contains face threatening acts. However, the FTA carried out by Mang Juhai to Mang Oding was only a fake face threat and was accepted and even enjoyed by the reader of the story. Although speech (4) is in the form of an FTA, it is accepted by the reader and enjoyed as humour.

Partington’s (2006) theory of affective faces and affiliation alignment, when applied to the data, provides insights here. The analysis indicates Palembangnese people accept and respond to the humour and directive evident in these three popular humour genres in Palembang city. Palembang’s culture-language practice may or may not be different from other languages and cultures. This shows the diversity of languages in a multicultural speaker society. The results of this study indicate that each language and culture have its own peculiarities. Humour and directives in Palembang, as a characteristic, show their role in the diversity of languages and cultures in multicultural Indonesian society. Language diversity, through research into Palembangnese humour and directives in Indonesia, can play a role in providing an understanding of the acceptance of differences in other cultures.

Conclusion: Illuminating distinctive cultural-linguistic practices in Palembangnese humour and directives in Indonesia

The distinctive features of Palembangnese humour and directives show a form of communication and community interaction in the city of Palembang. Alwi (2018) argues that the purpose of kelakar in Palembang society is one of the ways Palembang people use humour to alleviate the hard things to be easily understood. This paper, as a part of the bigger study of Palembangnese humour research, is the first to document the humour tradition in Palembangnese. Berkelakar [make a joke] as a tradition in the city of Palembang, is a communication tool to maintain social relations, close distances and explain and maintain this tradition for young people in Palembang. Therefore, these findings can be used as a basis for an understanding of how Palembang language works in the community.

The paper thereby helps the Palembang people with their own ‘artefacts’ and also promotes Palembangnese culture and humour to those outside the Palembang community. This paper makes explicit the implicit background assumptions and cultural explanations required to understand the data, since each script/topic can only be understood with additional explanations, as written in the data notes. The researcher, as a native speaker, uses her experience to interpret the data.

Gray (2003) states that experience can be defined as part of the process by which we express a sense of identity. This is also expressed through language. As an individual, the researcher is the mediator of the position we occupy in the social and cultural world find ourselves. As one of the local languages in Indonesia, Palembang reflects its own local wisdom. Wisdom in culture captures all the efforts and results of human and community efforts that are carried out and shown to provide human meaning. This research shows the wisdom of local Palembangnese culture through the analysis of the speech acts (in the form of scripts and/or topics) delivered in three different genres (Kelakar Bethook [Palembangnese humour], ceramah [Islamic speeches], and cerito Mang Juhai [Uncle Juhai stories]).

Moreover, in examining the constituent features of the language in practice (use) through the data sets, the paper evidenced and established patterns of directives and humour and FTAs working together to produce a cultural system. A cultural system is a system or unit that represents complexities as created and implemented by humans in society, in fulfilling and developing their lives and environment. It includes material and non-material things, which are carried out by humans through inheritance, education, teaching, and continuing habituation. In short, the cultural system is the highest controlling system in social action (Kistanto, 2008). Culture is the values and norms held by certain groups, so culture refers to the way of life of a society (Giddens, 2017). To understand culture, the ideological basis and tradition of thought and respect needs to be recognised (Jenks, 2005). The larger study from which this paper is drawn has illuminated the cultural system in Palembang by investigating in depth the main features of Palembangnese in the Kelakar Bethook, ceramah and cerito Mang Juhai. However, although there are differences in the important characteristics of each data set, this study found that they have more in common. The main similarities lie in the role of humour and the form of directives with FTA, which crosses social distance in the Palembang speech community as explained in the results and findings. This is evidenced by the acceptance of humour, directives, and FTA through laughter. Thus, the three data sets also operate as social artefacts and expressions of social customs in Palembang culture.

In conclusion, this research shows the distinctiveness of specific cultural-linguistic practices in Palembangnese humour and directives, as found in three genres of popular texts. The study shows the appropriateness of using Partington’s (2006) theory to analyse Palembangnese and culture and show the distinctiveness for each characteristic. Humour and directives in Palembangnese look like a sequence and pattern and have a distinctive relationship, as evident in the topicality, referentiality and collocational culture. People of different statuses can laugh, and nobody is losing face – in this way the humour creates solidarity, with laughter being the expression of agreement. It would be fruitful to pursue further research about the Palembangnese humour and the Palembangnese identity in order to understand the roots and identities of Palembang people, why do they live with kelakar [humour] in their daily lives and why they can be enjoyed and carried out for generations.

Acknowledgements

This paper presented at 11th Annual Postgraduate Research Conference at School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Australia. 27-28 June 2019, Paramatta city Campus. This paper is as part of the PhD thesis, entitled Distinctive cultural-linguistic practices in Palembangnese Humour and Directives in Indonesia: A Discourse Analysis. This PhD thesis is supervised by Associate Professor Robert Mailhammer, Dr Adrian Hale, and Associate Professor Anna Cristina Pertierra. I would like to thank my supervisory panel for all their support and advice and Dr. Susan Mowbray (Academic literacy advisor, Graduate Research School, Western Sydney University) for reading earlier drafts of this paper. This research is supported by Ministry of Religious Affairs scholarship (MoRA) Republic of Indonesia.

Notes

1 The first is the group Wong Jero, which is a descendant of nobles or reporters whose status is lower than those of the royal palace of Palembang. The second is the Wong Jabo group or ordinary people (Rochmiatun, 2017). In the beginning, there were many opinions that said that the Palembang tribe was a result of the fusion of several tribes such as Arabic, Chinese, and Malay. These tribes have migrated to Palembang for centuries and lived side by side with local residents for so long. In fact, during this time, mixed marriages occurred between the indigenous tribes and the immigrant tribes. Recently, from the three ethnic groups (Arabic, Chinese and Malay), this was born an ethnic named tribe of Palembang who had its own culture and customs. However, some Palembang people disagreed with this. They said that long before the arrival of Arabs, Chinese and Malays, the Palembang tribe had grown in Palembang and was the first occupant of the region. So, the Palembang tribe is a native tribe from Palembang and a separate indigenous community, not a mixture of several ethnic groups. As for the existence of an Islamic community in the city of Palembang, it can be proven by the existence of a figure named Raden Fatah. As is known that Palembang has an important position as the birthplace of a prominent figure of Raden Fatah, the first Islamic King in Demak (Rochmiatun, 2017). Thus, Palembang as a place that played a role in raising Raden Fatah, of course in the Palembang area at that time there had been Islamic scholars and community groups who had helped form or give Islamic teachings to Raden Fatah.

References

Adelaar, K. A. (2004). Where does Malay come from? Twenty years of discussions about homeland, migrations and classifications. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde, 160(1), 1-30.

Afriani, S. H. (2014). Realisasi Strategi Kesantunan Direktif di dalam Bahasa Palembang (Baso Pelembang) di Kalangan Anggota Kelompok Etnis Palembang di Kota Palembang: Sebuah Studi Sosial Budaya (Realization of the Directives Politeness Strategy in Palembang language (Baso Pelembang) among Members of the Palembang Ethnic Group in Palembang City: A Socio-Cultural Study. Paper presented at the Bahasa Ibu Pelestarian dan Pesona Bahasanya, Bandung, West Java.

Afriani, S. H. (2015a). An Introduction to Linguistics: A Practical Guide (Second ed.) Ombak Publisher.

Afriani, S. H. (2015b). The realization of politeness strategies in English directives among members of Palembangnese ethnic groups in Palembang, South Sumatra, Indonesia: Teaching Journey. Istinbath, 15(1).

Afriani, S. H. (2019). Linguistic politeness in Palembangnese directives in Indonesia and its implications for university teaching and lsearning. Paper presented at the Eleventh Conference on Applied Linguistics (CONAPLIN 2018).

Aliana, Z. A. (1987). Morfologi dan sintaksis bahasa Melayu Palembang (Morphology and Syntax of Palembang Malay Language): Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembang Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

Alwi, A. (2018). Karakter Masyarakat Islam Melayu Palembang (Characters of Islamic Palembang Malay society). Psikoislamedia: Jurnal Psikologi, 3(1).

Amalia, D., & Ramlan, M. (2002). Bentuk dan pemakaian ‘Baso Palembang Alus’ di kota Palembang (Form and The Use of ‘Baso Palembang Alus’ in Palembang city). [Yogyakarta]: Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Arif, R., Harifin, S., Usman, M. Y., Ayub, D. M., & Ratnawati, L. (1981). Kedudukan dan Fungsi Bahasa Palembang (A Position and Function of Palembang Malay Language). Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa.

Arifin, S. S. (1983a). Sistem Perulangan Kata Kerja dalam Bahasa Palembang. Laporan Penelitian. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa dengan Bantuan Proyek Pendidikan dan Pembinaan Tenaga Teknis Kebudayaan, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

Arifin, S. S. (1983b). Sistem Perulangan Kata Kerja dalam Bahasa Palembang (Verbal Repetition System in Palembang). Laporan Peneitian. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa dengan Bantuan Proyek Pendidikan dan Pembinaan Tenaga Teknis Kebudayaan, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

Attardo, S. (2001). Humorous texts: A semantic and pragmatic analysis. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1978). Universals in language usage: Politeness phenomena. In Questions and politeness: Strategies in social interaction (pp. 56-311): Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (Fourth edition. ed.): Los Angeles: Sage.

Dungcik, M. (2017). Kewujudan Bahasa Melayu Palembang Ditinjau Berdasarkan Segitiga Semiotik Ogden dan Richards (Kajian Semantik Terhadap Kosa Kata dalam Kamus Baso Palembang) (The Existence of Palembang Malay Language reviewed based on Semiotic Triangles of Ogden and Richards (A Semantic Study of Vocabulary in Baso Palembang Dictionary). (Doctoral PhD). University Brunei Darussalam, Brunei Darussalam.

Giddens, A. a. (2017). Sociology (8th edition. ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gray, A. (2003). Two articulating experiences. In A. Gray (Ed.), Research Practice for cultural studies. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Guidi, A. (2017). Humour Universals. In S. Attardo (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and humor. New York: Routledge.

Hamad, I. (2007). Lebih dekat dengan analisis wacana (More Close to Discourse Analysis). MediaTor (Jurnal Komunikasi), 8(2), 325-344.

Hanafiah, D. (1989). Kuto Besak: Upaya Kesultanan Palembang Menegakkan Kemerdekaan (Kuto Besak: Endeavour of the Palembang Sultanate to Establish Independence). Jakarta: Haji Mas Agung.

Irsan, M. (2017). Variasi Isolek Melayu di Sumatera Selatan. Madah: Jurnal Bahasa dan Sastra, 6(2), 137-150.

Jenks, C. (2005). Culture (2nd ed. ed.). New York: Routledge.

Kistanto, N. H. (2008). Sistem Sosial-Budaya di Indonesia (Socio-cultural system in Indonesia). Sabda: Jurnal Kajian Kebudayaan, 3(2).

Lockyer, S., & Pickering, M. (2005). Introduction: The ethics and aesthetics of humor and comedy. In S. Lockyer & M. Pickering (Eds.), Beyond a joke: The limits of humour. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

McMillan, C. (2000). Metafiction and humour in the great escape from city zoo. Papers: Explorations into Children’s Literature, 10(2), 5.

Morgan, M. (2014). Speech communities. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Muhidin, R. (2018). Leksikon Kekerabatan Etnik Melayu Palembang (Kinship Lexicons of Palembang Malay Ethnics Group). Ranah: Jurnal Kajian Bahasa, 6(1), 84-99.

Oktovianny, L. (Ed.) (2004) Naskah Kamus Palembang. Palembang: Balai Bahasa Palembang.

Oxford English Dictionary. (2019). Comedy of errors. Retrieved from https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/34857225?redirectedFrom=comedy+of+errors+

Partington, A. (2006). The linguistics of laughter: A corpus-assisted study of laughter-talk London: Routledge.

Purnama, H. L. (2008). Makian dalam Bahasa Melayu Palembang: studi tentang bentuk, referen, dan konteks sosiokulturalnya (Cursing in Palembang Malay: a study of form, referent, and its sociocultural context). Sanata Dharma University.

Rochmiatun, E. (2017). Bukti-bukti Proses Islamisasi di Kesultanan Palembang (Evidence of the Islamization Process in the Palembang Sultanate). TAMADDUN: Jurnal Kebudayaan dan Sastra Islam, 17(1), 1-17.

Schnurr, S., & Plester, B. (2017). Functionalist Discourse Analysis of Humour. In S. e. Attardo (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and humor. New York: Routledge.

Searle, J. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. London: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. (1976). A classification of illocutionary acts. Language in Society, 5(01), 1-23.

Susilowati, D. (2006). Analisis Semantik Verba ‘Menyakiti’ dalam Bahasa Melayu Palembang (A semantics analysis of Verb ‘ menyakiti’ in Palembangnese). Bidar: Majalah Ilmiah Kebahasaan dan Kesustraan (Language and Literature Scientific Magazine), 2 Number 1.

Sustianingsih, I. M., Yati, R. M., & Iskandar, Y. (2019). Peran Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin I dalam Pembangunan Infrastruktur di Kota Palembang (1724-1758) (The role of Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin I in Infrastructure Development in the City of Palembang 1724-1758). TAMADDUN: Jurnal Kebudayaan dan Sastra Islam, 19(1), 49-62.

Tiani, R. (2018). Korespondensi Fonemis Bahasa Palembang dan Bahasa Riau (Phonemic Correspondence of Palembang language and Riau language). Nusa: Jurnal Ilmu Bahasa dan Sastra, 13(3), 397-404.

Trisman, B., Amalia, D., & Susilawati, D. (2007). Pedoman Ejaan Bahasa Palembang (Palembang Language Spelling Guidelines): Balai Bahasa Palembang (Provinsi Sumatera Selatan).

Tsakona, V. (2017). Genres of humor. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

Turner, G. a. (2014). Understanding celebrity (Second edition. ed.) Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning as a social system. Systems Thinker, 9(5), 2-3.

Wibowo, G. H. (2018). Pengaruh Daya Tarik Maskot Mang Juhai terhadap Minat Pembaca di harian Umum Palembang Pos (Studi Kasus Masyarakat RT 06 RW 02 Kelurahan Sekip Jaya Kecamatan Kemuning Kota Palembang) (Effect of Mang Juhai Mascot’s Attractiveness on Readers’ Interests in the daily Palembang Pos (Case Study of Palembang Community RT 06 RW 02 Sekip Jaya Village, Kemuning District Palembang City)). (Bachelor). UIN Raden Fatah Palembang, Palembang.

About the author

Susi Herti Afriani is a PhD candidate in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts at Western Sydney University, Australia. Susi holds a master’s degree in linguistics from the University of Indonesia and is a linguistic lecturer at the State Islamic University (UIN) Raden Fatah Palembang under the Ministry of Religious Affairs, Republic of Indonesia. Susi has several publications including Kelakar Bethook in Palembang Malay Language: A Linguistic Analysis in the Journal of Malay Studies (2019). Her PhD is titled ‘Distinctive-cultural linguistics practices in humour and directives in Palembang Malay in Indonesia’. Her research interest are pragmatics, discourse analysis, semiotics and Islamic studies. This research was supported by MORA scholarship ref. 1377/Dj.I/Dt.I.IV/4/Hm.01/08/2016.