Ready or not: A survey of Australian journalists covering mis- and disinformation during the coronavirus pandemic

Anne Kruger

University of Technology (UTS), Sydney

Lucinda Beaman

University of Technology (UTS), Sydney

Monica Attard

University of Technology (UTS), Sydney

Abstract

In mid-February 2020, the Director General of the World Health Organisation (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, announced: ‘We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic’ (Ghebreyesus, 2020). A survey conducted by First Draft’s Sydney bureau during the coronavirus restrictions showed only 14.1 percent of Australian journalists said that they have had adequate training and support to deal with mis- and disinformation. Yet journalists were faced with reporting on a proliferation of online narratives including dangerous health messages, misrepresentations of ethnic and Indigenous communities and attempts to fuel anti-Asian racial divides.

Based on a survey, this paper provides a background to the attitudes, experiences and urgent needs for the future as Australian journalists report on mis- and disinformation. Against a backdrop of COVID-19 related business model challenges and in an environment where consumers are engaging with information digitally at historically high levels, the ability of journalists to recognise and counter mis- and disinformation and be supported in their pursuit of non-contaminated information is at its peak requirement.

Introduction and aims

In mid-February 2020, the Director General of the World Health Organisation (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, told global leaders: ‘We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic’ (Adhanom Ghebreyesus, 2020). Throughout the resulting coronavirus pandemic, journalists worldwide have been faced with reporting on a proliferation of online narratives including dangerous health messages and conspiracy theories, to heightened political and racial divides spilling from online to the offline world, with often dangerous and sometimes deadly consequences. Professional journalists and newsroom leaders have an important role in democratic society (Bennet & Livingston, 2018) to not only make sense of the influx of online information but also to ameliorate the harmful impacts of mis- and disinformation. Based on its findings, this research argues preparation and support for journalists to navigate within this digital ecosystem of ‘information pollution’ (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017, p. 4) has been ad-hoc, arguably exacerbated by an industry in transition from a drawn-out destabilisation of its business models.

Even before the ‘infodemic’, the rise and proliferation of mis- and disinformation within a digital participatory culture (Kruger, 2019; Hine, 2015) posed an urgent challenge to journalists as they attempted to report on issues of public interest. In 2017, scholars argued:

… contemporary social technology means that we are witnessing something new: information pollution at a global scale; a complex web of motivations for creating, disseminating and consuming these ‘polluted’ messages; a myriad of content types and techniques for amplifying content; innumerable platforms hosting and reproducing this content; and breakneck speeds of communication between trusted peers (Wardle & Hossein Derakhshan, 2017).

However, despite the role of quality journalism to inform the public, training and support for journalists to carry out their role within the complex digital information ecosystem has not kept pace with this aspect of the technology. Research in 2019 by the US-based think tank, Institute for the Future (Carter Persen, et al., 2019a), documented concern at the low numbers of journalists who felt they are prepared in a world of mis- and disinformation: ‘only 14.9 percent of journalists surveyed said they had been trained on how to best report on misinformation’ and ‘more than 80 percent of journalists admitted to falling for false information online’ as reported by the Poynter Institute (Funke, 2019).

In late 2019, First Draft’s Sydney bureau sought permission from IFTF investigators to replicate the US study in the Australia-APAC region. Permission was granted by the IFTF and research ethics by the University of Technology Sydney to conduct separate studies using localised questions and context where necessary for Australia, New Zealand and a general Pacific nations study. As noted in the methodology section below, follow up interviews allow for a more conversational tone for the participants to elaborate on points in the survey.

The aim of the study is to better understand journalists’ attitudes, experiences and ability to work within the mis- and disinformation ecosystem and their level of relevant training. It enquires as to whether journalists have come across mis- and disinformation online in the course of their daily duties, how they dealt with this, and how prepared they felt to do this. The research will allow the investigators to discover how vulnerable and prepared journalists are in this time of ‘infodemic’, particularly as media business models are in rapid transition. This would allow the researchers to consider, if necessary, areas where potential solutions and support may be provided in future, for example to inform better design of verification training and resources with a longitudinal approach.

This paper reports on results from the first stage, focused on Australia. Whilst planning had been underway since the start of 2020, the Australian iteration of the survey was conducted in the midst of the pandemic between May 27-July 13. Findings reflect a similar, if not worse concern in Australia to the US study: only 14.1 percent of Australian journalists felt they had adequate training and support for reporting on mis- and disinformation. While the IFTF survey found 80 percent of journalists admitted to falling for false information online; the Australian survey specifically asked whether journalists had included mis-or disinformation in their reporting – to that, 44.3 percent of the respondents answered ‘yes’. When asked why, the answers included a lack of knowledge in how to produce reports about mis- and disinformation, as well as a lack of skill to make an assessment, time constraints, and that someone in a more senior position made the incorrect decision.

The following begins with definitions and a short literature review placing initial findings from the first iteration of surveys within an Australia context and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The literature review is followed by a background and methodology, results and findings and future recommendations.

Definitions and literature review

From 2016 the term ‘fake news’ was brought into the modern lexicon after the US elections; however, this term has since been used as a weapon against professional journalists. The term ‘information disorder’ has been adopted in scholarly and regulatory studies to cover the types, phases, and elements of mis- and disinformation in the digital ecosystem:

While the historical impact of rumours and fabricated content have been well documented, we argue that contemporary social technology means that we are witnessing something new:

information pollution at a global scale; a complex web of motivations for creating, disseminating and consuming these ‘polluted’ messages; a myriad of content types and techniques for amplifying content; innumerable platforms hosting and reproducing this content; and breakneck speeds of communication between trusted peers. (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017)

To help bring order to this environment, First Draft distinguishes between ‘disinformation’, ‘misinformation’ and ‘malinformation’ (Wardle, 2018):

- Disinformation is false information that is deliberately created or disseminated with the express purpose to cause harm. Producers of disinformation typically have political, financial, psychological, or social motivations.

- Misinformation is information that is false, but not intended to cause harm. For example, individuals who don’t know a piece of information is false may spread it on social media in an attempt to be helpful.

- Malinformation is genuine information that is shared to cause harm. This includes private or revealing information that is spread to harm a person or reputation.

The internet spurred a ‘continuous flow of information and misinformation on digital participatory platforms’ (Kruger, 2019, p. ii). Journalists must sift through and sort the influx of information to find reliable content and debunk that which is not, all the while being vulnerable to unwittingly spreading incorrect information, as well as being targets of misinformation campaigns. Scholarly research into user-generated content (UGC) and resulting production implications for journalism have been well documented. However, despite the urgency, there has been little scholarly research into the related training needs of journalists in online verification and their systematic monitoring of social media for mis- and disinformation (Kruger, 2019). A study by Data & Society (Marwick & Lewis, 2017, p. 3) noted ‘the media’s dependence on social media, analytics and metrics, sensationalism, novelty over newsworthiness, and clickbait makes them vulnerable to such media manipulation.’

Online misinformation campaigns have a number of tools to utilise the spread of unreliable, yet attractive content – from bots to trolls, memes and now artificial intelligence such as deep fakes. In addressing an era of digital information manipulation, journalism scholars have noted that educators must not only train journalism students in how to report accurately, but also commit ‘to a process of verification that shows the rigour behind the best kind of journalism’ (Richardson, 2017, p. 1) Yet there has been even less scholarly research into the best training techniques for practicing journalists to monitor, discover and verify social media messages, against growing constraints such as fast paced deadlines and decreased staff numbers.

Some countries such as Australia have traditionally been viewed as not prone to ‘fake news’ (Kaur et al., 2018), particularly in comparison to the US in 2016, and violent offline ramifications from online messages in areas of Asia such as the Philippines and Myanmar. However, the spread of mis- and disinformation has recently been documented in Australia where hate speech and misinformation were linked during the 2019 federal election. Racial prejudice, immigration fear campaigns as well as so-called zombie rumours proliferated in what was dubbed as ‘Australia’s first social media election’ (Warren, 2019). Furthermore, the overlap of disinformation with hate speech was documented earlier in 2019 in the tragic Mosque shooting in Christchurch, where the now convicted Australian shooter used online social media to amplify his extremist views, exposing vulnerabilities and taking mainstream media by surprise.

At the time of the survey in Australia, news consumption had increased in the wake of the bushfires and the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. The Public Interest Journalism Initiative (PIJI) has been documenting changes to the Australian media landscape using visualisation tools in its Australian Newsroom Mapping Project (PIJI, 2020). At the time of the survey, PIJI (2020) noted that since January 2019, Australia had experienced some 157 newsroom temporary or permanent closures. For some, the reason for the closures or contractions predated COVID-19, but other changes did reflect the COVID-19 induced contracted advertising environment.

This contracted environment came at a time of significantly increased audience numbers and news consumption due to the December 2019-March 2020 bushfire season and COVID-19 lockdowns. The top 10 news sites in Australia increased audience viewership by 57 percent in March 2020 alone according to the Nielsen Digital Content Ratings (Helliker, 2020). A University of Canberra study (Park, et al., 2020), found 70 percent of respondents had increased the number of times they accessed news on a daily basis. In a febrile environment of reduced newsroom staff numbers, audiences requiring and accessing more news-based information on a daily basis has been on the rise.

Background and methodology

First Draft works to ‘empower people with knowledge and tools to build resilience against harmful, false and misleading information’ (First Draft, 2020). It formed as a ‘non-profit coalition with nine founding partners in June 2015, to provide practical and ethical guidance in how to find, verify and publish content sourced from the social web’ (First Draft 2020). First Draft’s headquarters are administered in London; its US subsidiary is a non-profit, with offices at Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York. In 2019, First Draft opened a Sydney bureau with the view to further expand in the APAC region.

The Sydney bureau is supported via First Draft’s not-for-profit headquarters in the UK which receives funding via donors as listed on its website’s ‘about’ page (First Draft, 2020). The Sydney bureau is affiliated with the University of Technology Sydney’s Centre for Media Transition. First Draft conducts training and provides a free library of online courses, tool kits and resources to help both journalists and the public understand and manage the mis- and disinformation ecosystem. The Sydney bureau’s goals include to better understand and support journalists in Australia, New Zealand, and Asia-Pacific. Therefore, it should be noted, any survey findings may help to inform future design, and in particular respond to the training needs of professional journalists.

The First Draft US bureau facilitated initial requests to the Institute for The Future (IFTF) in order for the Sydney bureau to seek permission to replicate, in part, the IFTF study as noted in the introduction. The IFTF study drew from an original survey of 1,018 journalists, 22 semi-structured interviews (from the US and UK July-November, 2018), and secondary sources. According to the IFTF executive summary, in the wake of the 2016 US elections, ‘the field of journalism has been upended by revelations that the spread of false information is not only abundant but has also potentially undermined democratic outcomes’ (Carter Person, 2019). The report noted however that little ‘is known about how the proliferation of false information has affected the field of journalism’ (Carter Persen, 2019). Findings were presented in three research briefs: ‘False information in the Current News Environment’; ‘The Effects of False Information on Journalism’; and ‘Mitigating the Negative Impact of False Information’.

The IFTF granted written permission and provided non-identifiable methodology and survey questions to the First Draft Sydney bureau in February 2020. This paper focuses on findings from the first phase of the research, focused on Australian journalists. This will form part of a larger body of work being undertaken by the Sydney Bureau of First Draft, with a New Zealand version of the survey in progress at the time of writing. The bureau also intends to roll out a survey relevant to Pacific nations in 2020/2021.

This paper focuses on initial results from the first phase of the research focused on Australia: A total of 170 journalists participated (n=170). A total of 12 journalists were interviewed in the smaller scale interview. The survey was conducted in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic between May 27-July 13 2020, by First Draft’s Sydney bureau, based at the Centre for Media Transition, UTS. Follow up one-to-one interviews were held with a smaller round of journalists in September. These were initially planned to be conducted either in person or via video conference. Due to the subsequent coronavirus protocols, all interviews were held via video conference. The First Draft Sydney bureau engaged research consultancy CoreData to conduct primary research via a quantitative online survey. The large-scale survey consisted of approximately 40 questions including multiple choice, Likert scales and open-ended answers for ‘other’ information if required. The research by the First Draft Sydney bureau replicates a contextualised version of the methodology and survey design as used by the Institute for the Future in the US. The First Draft bureau editor and a First Draft senior researcher reworded and adapted the survey questions to suit its non-US participants. The survey was for professional journalists only – whether full time, part time, casual or freelance, rather than those who work in related fields but do not identify their main role as a journalist. As the survey coincided with numerous pandemic-related and business-related newsroom closures and layoffs, the researchers allowed journalists who had recently lost their jobs in these circumstances to still apply.

Questions in the IFTF and First Draft Australia surveys both focused on the following:

- Demographics and their journalism role (such as editor, full time or freelance, what platform – online/newspaper, broadcast etc.).

- Concern about mis- and disinformation on issues such as politics, climate, health and vaccine related topics, immigration – with language adjusted for the Australian setting. The Australian survey further added a contextualised question asking, ‘how concerned are you about the spread of false information for the following groups of people in Australia?’ This focused on concern for minority groups and ethnicities.

- To what extent they were concerned about the spread of mis- and disinformation on specific social media/platforms.

- If in their work, participants have reported on stories that involve mis- or disinformation; if they have included mis- or disinformation; and if they ever felt it was counterproductive to report on false information.

- Training: how prepared they feel from training; what relevant training they have had; follow up from training; whether they feel they have adequate training or support from their employer.

- What further support they would like with regards to online verification training and monitoring.

The Australian survey questions focused on relevant examples – for example, while the US survey pointed to the 2016 presidential elections, the First Draft Sydney bureau wanted to discover in the Australian survey when its respondents first thought mis- and disinformation was a threat from an Australian perspective; and what first made them realise the online spread of mis- and disinformation was a significant problem for Australia. Examples to choose from included the recent bushfires, coronavirus pandemic, elections, political leadership spills, the 2017 same sex marriage survey, viral hoaxes and health scams dating back to 2013, and ‘other’ with a text box to expand, as well as an option for ‘nothing – I don’t think it’s a significant problem in Australia’. The First Draft survey also asked more specific questions about how they discern the tipping on when to report on misinformation (weighing the risks versus the benefits); and their willingness to collaborate with other newsrooms and journalists in an effort to help make sense of disinformation.

Survey findings

As noted above, the aim of the survey is to better understand Australian journalists’ attitudes, experiences and ability to work within the mis- and disinformation ecosystem. This section highlights the results and findings of the Australian survey, being the first in the series conducted by First Draft’s Sydney bureau. General comparisons with the US study are also given against the main survey question topics highlighted in the methodology, but greater detail into the Australian experience is provided in line with the aims of this paper.

The top five key insights from the survey found:

- Concern is pervasive among journalists: Practically all journalists hold professional concerns about mis- and disinformation. Verbatim responses reinforced this and highlighted a belief among some that misinformation and attacks on the media itself are undermining public trust and assisting in the spread of mis- and disinformation and its acceptance by the public.

- Journalists feel ill-equipped: Few journalists report that their education covered monitoring and verification of information using online tools. While their more recent training typically did, it was not often covered in detail. As a result, most journalists do not feel they have adequate training and support to report on mis- and disinformation campaigns.

- Journalists want to upskill: There is a widespread lack of confidence among journalists, in their ability to uncover links to sources underpinning mis- and disinformation, as well as tracking back to original sources. Confidence is highest among those who have made some attempt to upskill recently, but support for applying new knowledge is rare. As such, training is the thing most say would benefit them.

- Newsroom support appears lacking: Almost half the journalists surveyed had included mis- and disinformation in a report. This was due to either a lack of time or the placement of a piece of information (a quote from a politician for example), that they knew, or suspect to be misleading/incorrect, but without the full correct information or context. While practically all respondents report taking precautions, less than two in five said their newsroom leaders would be very supportive of them taking more time to fact-check and verify. The same proportion believe they would have support to undertake training on company time, or at company expense.

- There is a lack of clear guidance: Two in three respondents wanted guidelines for responsible reporting on mis- and disinformation. The same number believe mis- and disinformation ‘expert’ journalists should be in every newsroom. Despite this, just 7.1 percent said their newsroom had a formal ‘tipping point’ policy to guide reporting decisions regarding mis- and disinformation (CoreData, 2020).

As noted in the introduction, the US survey found 80 percent of journalists admitted to falling for false information online; however, the Australian survey specifically asked whether journalists had included mis-or disinformation in their reporting, to which a total of 44.3 percent of the respondents said yes. Nearly half of those who answered yes, responded it was due to the format of the story – they were reporting on what was said. For example:

… traditional journalistic practice places value on giving ‘both sides’ to the story. Conflicting perspectives are routine … The skill of political, corporate figures, activist groups of all kinds is to tell and insist on a marginal half-truth. Untangling it can be complex, time consuming and confusing’. (59-year-old, male, NSW).

While another respondent noted:

… it’s a quote from an authority figure or politician that is demonstrably false and while I do my best to debunk it, nobody cares, except for the quote. (26-year-old, male, Victoria).

Meanwhile 36 percent of those who said yes to including mis- or disinformation responded they did not feel equipped or had too little time to make an assessment. Twenty two percent noted it was the decision of a colleague who was more senior. This was followed by 18 percent who noted they believed it to be correct at the time and nearly 17 percent who said they were unable to find a source that provided correct information or context at the time.

The Australian survey also found that formal upskilling in monitoring and verification is rare, and those who do, typically spend three days or less a year with workplace follow-up support. But there was positive news, with 75 percent or more clearly open to more collaboration to help fellow journalists navigate the influx of mis- and disinformation. The IFTF survey also conducted a collaborative training exercise where the intervention found participants were more likely to improve in their accuracy in identifying mis- and disinformation (Joseff, 2020, p. 7).

Demographics

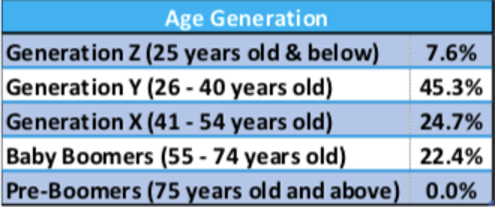

A total of 54.1 percent of respondents identified as female, 43.5 percent male, 1.2 percent non-binary, and 1.2 percent preferred not to say. The majority of respondents were 30-39 years old (28.2 percent), followed by 29 years old and below (23.5%), 50-59 years old (18.8%), 40-49 years old (17.1%) and 60 years old and above (12.4%). As Figure 1 below shows, the age generation of the majority of respondents was Generation Y, followed by Generation X.

Source: CoreData

A total of 1.2 percent identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander; 7.1 percent as culturally and linguistically diverse; 8.8 percent as LGBTQIA+; 5.9 percent from an ethnic minority and 3.5 percent from a religious minority.

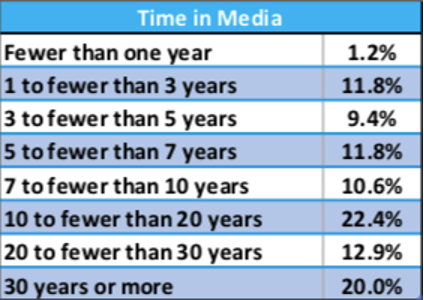

As Figure 2 below shows, the majority of respondents had worked ten or more years in media, with 13 percent three years or fewer.

Source: CoreData

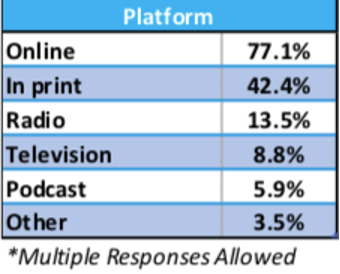

The majority of respondents (77.1%) work in online media, followed by print (42.4%), then radio (13.5%), television (8.8%). Note multiple answers for overlaps in medium were allowed, as seen in Figure 3 below.

Source: CoreData

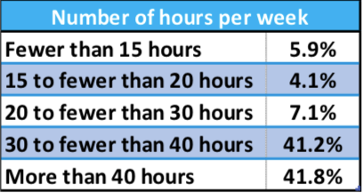

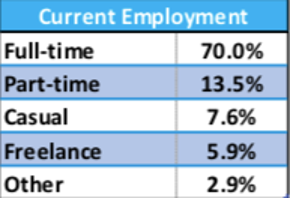

As Figures 4 and 5 show below, the majority of respondents worked full time and worked more than 40 hours per week:

Source: CoreData

Journalists’ awareness of mis- and disinformation in Australia

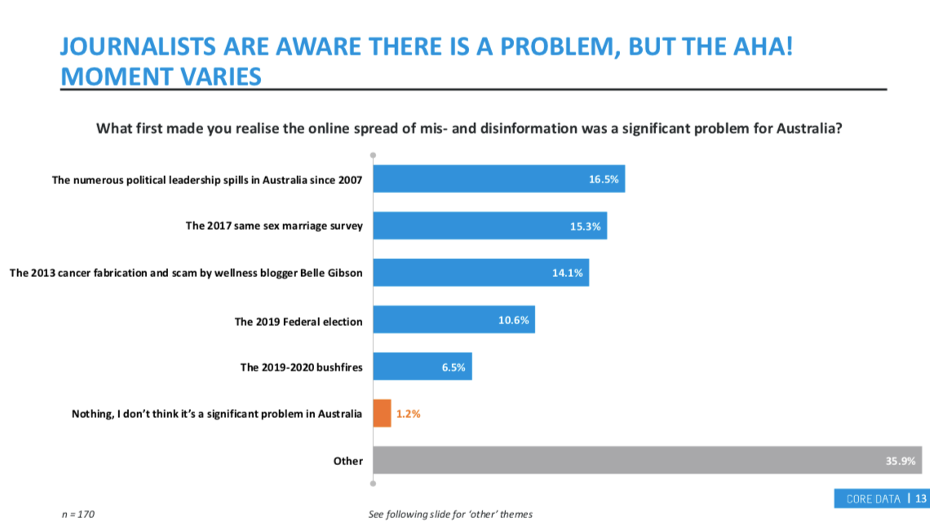

Professional concern about the spread of mis- and disinformation is almost universal. Responses noted journalists are aware there is a problem, the moment varies regarding when they first realised the online spread of mis- and disinformation was a significant threat. Examples to choose from in the survey question included the recent bushfires, coronavirus pandemic, elections, political leadership spills, the 2017 same sex marriage survey, viral hoaxes and health/wellness scams dating back to 2013, and ‘other’ with a text box to expand, as well as ‘nothing – I don’t think it’s a significant problem in Australia’. As Figure 6 below illustrates, the largest group (35%) chose ‘other’. This was followed by 16.5 percent who chose the numerous political leadership spills in Australia since 2007; followed by 15.35 percent who noted the 2017 same sex marriage survey, and 14.1 percent chose wellness scams. Interestingly only 10.6 percent and 6.5 percent respectively chose the more recent 2019 federal election and bushfires, which indicates an earlier awareness of the problem of misinformation in Australia before the recent events and crises.

Source: CoreData

Verbatim responses from the largest group ‘other’ raised concerns about political and social media misuse and undermining of experts. Many found it hard however to pinpoint an exact moment or event when they first realised mis- and disinformation was a problem for Australia:

All of the above. I have been observing the growing spread of mis- and disinformation over two decades as a journalist. (45-year-old male, Victoria).

It wasn’t one big event. It’s everywhere, and I’m not sure when it first concerned me. Feels like forever. (28-year-old female, NSW).

No particular moment, it has been clear for some time (27-year-old male NSW).

Has been a problem for as long as I can remember. (29-year-old male NSW).

Just news in general – since social media there has been a grab for sensationalism, untruths etc. (56-year-old female, South Australia).

Seeing incorrect information spread by ‘friends’ on social media platforms from mid-2010s. (35-year-old female NSW).

Talking to people and realising they truly believe the misinformation/disinformation. (28-year-old female, Queensland).

The broader adoption of social media in the late 2000s and the ease with which content could be encouraged to spread. (60-year-old male, NSW).

While still unable to pinpoint an exact moment, others pointed to issues of climate change and immigration (still in the ‘other’ category):

Emergence of climate deniers in the mainstream political discussion. (36-year-old male, Queensland).

The huge platform that was given to climate denial for decades across all media. (31-year-old female, NSW).

Community sentiment and government policy relating to climate change, and to refugees/immigration. (34-year-old female, NSW).

Topics and issues of concern

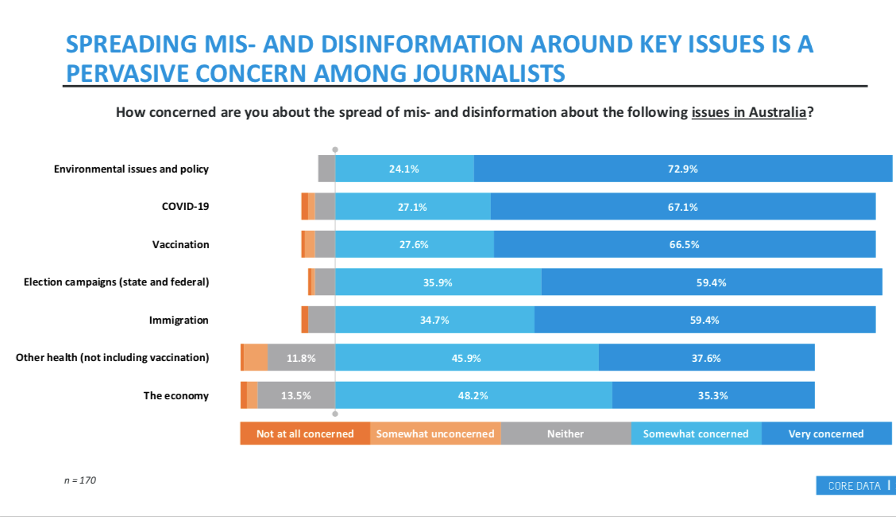

A separate question then asked how concerned Australians were about the spread of mis- and disinformation about issues from a specific list including environmental issues and policy, the coronavirus pandemic, vaccination, election campaigns, immigration, other health (not including vaccination) and the economy. As Figure 7 shows, the top concern ‘very concerned’ was environmental issues and policy (72.9%), followed by COVID-19 and vaccination. As Figure 7 illustrates, these came ahead of elections, immigrations, other health and the economy.

Source: CoreData

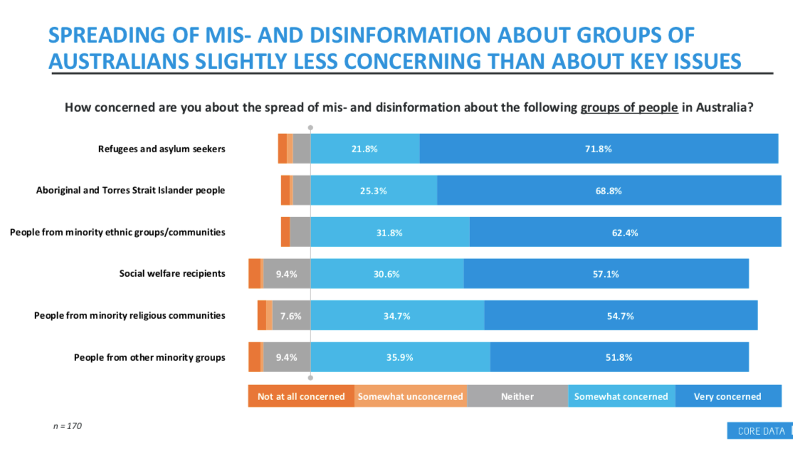

This was followed by a question to discover how concerned respondents were about the spread of mis- and disinformation about specific groups of people in Australia such as minorities. As Figure 8 shows, the top concern (71.8%) related to refugees and asylum seekers:

Source: CoreData

Respondents were given the opportunity to add any other areas in which the spread of mis- and disinformation concerned them. The undermining of experts, the use of platforms to push political agendas and the speed at which misinformation spreads on social media were key points. For example, typical comments regarding the undermining of experts included:

The reporting of scientific and medical studies is a specialised skill. I’m worried we are losing the expertise in newsrooms to report on medicine well, and that some newsroom leaders don’t appreciate the time it takes to report on a new study well … Context is critical. (34-year-old female, Victoria).

General undermining of experts in any field is a serious problem. For example, renewable energy and infrastructure projects. (28-year-old male, Victoria).

Scientists, academics and other experts. Mis/disinformation aims to undermine the very notion of expertise. (57-year-old male, Victoria).

Comments regarding political manipulation concerns ranged from political operatives hiding behind anonymous social media accounts, to political agendas being pushed online via mis- and disinformation:

I am concerned about political operatives hiding behind the cover of anonymous/fake social media accounts to spread mis/disinformation about political rivals. I am concerned this has been corrupting the political process. (45-year-old male, Victoria).

The use of misinformation to further the agenda of specific interest groups, particularly the disinformation being spread [by] politicians, political parties and government agencies. (57-year-old, male NSW).

Yes, I strongly believe many Australian politicians – of all parties – spread mis- and disinformation about many, many topics deliberately. (65-year-old female, Queensland).

And regarding social media, comments typically focused on concerns over the ease with which misinformation can spread:

On social media, the speed and spread of misinformation is terrible. (55-year-old male, Queensland).

Social media news feeds empower disinformation and misinformation. (48-year-old male, NSW).

Concerns about platforms

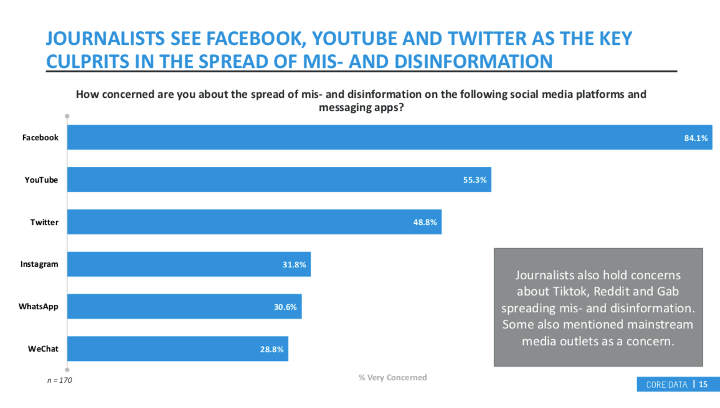

The survey asked respondents to rate how concerned they were about the spread of mis- and disinformation on social media platforms and apps on a rating from 1 to 7, where 1 was not at all concerned and 7 was extremely concerned:

As Figure 9 shows, results revealed journalists see Facebook, YouTube and Twitter as key platforms of concern in the spread of mis- and disinformation. Journalists could also elaborate on ‘other’ where Tiktok, Reddit and Gab were added as areas of concern for the spread of mis- and disinformation. Some also noted mainstream media outlets as a concern.

Source: CoreData

Support and solutions

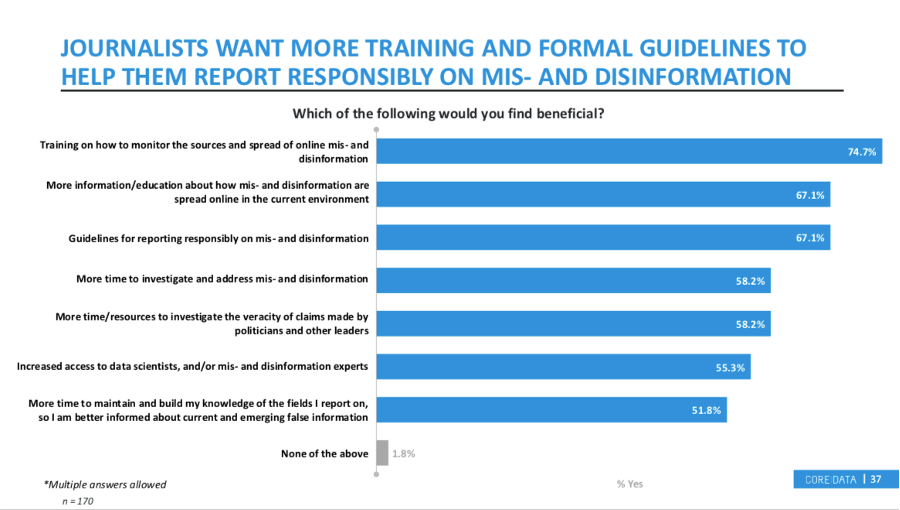

An overwhelming 98 percent of respondents want more training and formal guidelines to help them report responsibly on mis- and disinformation. As Figure 10 illustrates, this includes understanding how mis- and disinformation spreads online in the current environment; guidelines on how to report responsibly; as well as more time to investigate claims (including by politicians); increased access to data scientists of experts as well as more time to maintain and build their knowledge of the field the journalists report on, so they are better informed about current and emerging false information.

Source: CoreData

Journalists expanded on their answers which showed an overwhelming desire for support in the workplace:

I don’t feel I have workplace support to pursue this kind of work despite increasing demand. There is a massive perception gap with higher ups who seem to believe online verification can be done with a few clicks on a mouse. Too often I’m sent on errands to verify stuff that’s had no impact. I feel my workplace has failed to listen to warnings about building long term verification teams/systems, relying instead on a few younger journalists/producers to do the work for them. (32-year-old male, NSW).

It’s a topic every journalist cares about but the support, time and resources aren’t always there to allow for any significant progress to be made. (30-year-old female, NSW).

Training at work is only about updated software systems – it would be amazing to have broader professional training or support – perhaps a point system like medicos have. Also, would be good if journalists supported each other more. Our work culture is silent and focused on deadlines only – no feedback, no discussion no ambition just get the job done and go home. (58-year-old female, Queensland).

Misinformation is becoming an issue in even the most innocuous of stories. I would love to have more skills to address this for my audience. (38-year-old female, NSW).

I used to work at a mainstream metro newspaper, and speed and clicks were valued over accuracy and meaningful stories designed to help people understand an issue or event. We need to change the culture of publications – major newsrooms especially – to priorities giving people meaningful and true information. (28-year-old female, NSW).

To help mitigate some of these issues, two in three of respondents agreed newsrooms should have journalists specifically training in identifying, tracking and responding to mis- and disinformation; and at least 75 percent of respondents willing to collaborate with other journalists to help identify major themes and events related to mis- and disinformation, with 20 percent stating they ‘maybe’ willing to collaborate.

Follow up interview findings

As noted above, the IFTF study drew from an original survey of 1,018 journalists, 22 semi-structured interviews from the US and UK July-November 2018 (Carter Persen et al., 2019a). The Australian survey also drew on semi-structured interviews. All of those who indicated via the original survey they would be open to the one-to-one follow up interview were emailed and asked to participate via video within a specified time frame.

The follow up questions from the Australian journalists used the same general themes as the US study beginning with defining the topic at hand; followed by the impact of mis- and disinformation on journalists’ work/ producing news; and ideas about interventions to mitigate the impacts of mis- and disinformation.

Defining the topic at hand

In the first area of defining the topic and hand, the IFTF interview report noted:

the majority of interviewed journalists correctly categorised misinformation as false information accidentally spread by the unsuspecting public, and disinformation as false information intentionally spread to achieve political, social, or financial goals’ (Carter Persen et al., 2019b, p. 4).

The term ‘fake news’ had various meanings, but typically ‘ranged from fabricated news that could include disinformation or misinformation to a partisan slur used to attack the media or a maligned label for anything a given politician or member of the public does not like’ (Carter Persen et al., 2019a, p. 4). While most respondents referred to ‘fake news’ as a separate phenomenon, they also felt that knowledge of misinformation online and disinformation campaigns, particularly knowledge of them getting covered by journalists, was feeding the fire for those accusing the media of ‘fake news’ (Carter Persen et al., 2019b, p. 4).

The Australian iteration had similar responses to that of the IFTF study with regards to defining the topic at hand. The researchers note a female Australian newsroom leader working under lockdown conditions at the time of the video interview in Melbourne reflects a summary of the majority of the respondents’ findings:

Misinformation broadly speaking is an umbrella term, information that isn’t that correct, spread inadvertently sometimes. Disinformation is deliberately manipulated information and put out there for whatever purpose it might be – to make money, get clicks, run a political agenda, activism. I know there’s this new mal-information my understanding it’s private information put out there for nefarious reasons.

This, along with the majority of answers was in line with the First Draft definitions. Regarding the term ‘fake news’, she added:

We all started off being very cautious of the term ‘fake news’ simply because people have used it to mean different things – some mean not accurate information, others mean information they don’t like. It’s a problematic term, now connected with the era of Trump.

And while cautious not to include ‘fake news’ in her own vocabulary, she reflected on realities in the news production process:

Generally speaking, I prefer not to use that term because it can be vague, I tend to use ‘false’ more, but of course ‘fake’ is now widely used and we as fact checkers can’t ignore that. You have to be able to engage with that term.

The role of politics and politicians as spreading mis- or disinformation was a concern for most respondents. It was also something most journalists found difficult to quantify or prove. A young female reporter based in Canberra noted:

Sometimes we forget about dog whistling, sometimes people will put something out that is factually correct but the way they’re putting it out and why they’re putting it out it is to push forward disinformation.

However, a senior writer with a background in economic journalism noted she was acutely aware of the origins of the many sayings and political manoeuvres at press conferences and is able to call politicians out for misuse of terms and identify real policy implications.

The impact of mis- and disinformation on journalists’ work/producing news

In the areas of the impact of mis-disinformation on journalists’ work/ producing news, the IFTF survey and interviews were conducted at a time when viewership and subscription numbers had increased in the wake of the increased prevalence of the term ‘fake news’: ‘respondents mentioned that while trust had declined among some subsets of the population, demand and respect for quality journalism has increased in other subsets of the population as a direct result of the focus on false information”(Carter Persen et al., 2019c, p. 2). This also led to a large Washington DC newsroom increasing ‘staff by over 65 percent in recent years’ (Carter Persen et al., 2019c, p. 2).

As noted in this paper’s literature review, at the time of the survey in Australia, readership numbers increased – in the wake of the bushfires and the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. However, newsroom staff numbers experienced a severe cut, with significant redundancies of largely senior journalists announced and closures of traditional newspapers. Across both the IFTF and the Australian follow up interviews, journalists responded that the current environment made them increasingly careful about their sourcing techniques. In the Australian survey, one interview respondent from a fact checking unit noted an increase during coronavirus from their ‘bread and butter’ reporting with political fact checks, to include a focus on verification. The respondent was aware of the need to discover where the information originates from and the extra level of work this requires.

The majority of interviewees also noted the care they had to apply to sources and tip offs from Facebook groups and comments. Newsrooms with Facebook pages that allow comments took up a large focus of the production work, ‘you moderate it quite heavily, you decide if it should stay there or just someone sharing propaganda,’ noted a female respondent from regional Australia. A male respondent from a small country town where an anti-lockdown video went viral during coronavirus noted his news organisation was particularly cautious to avoid repeating comments and posts from ‘fringe pages’. He had seen other media being used to spread unfounded conspiracy theory messages in reports using the terminology from the fringe pages. ‘Two years ago, this didn’t happen much, but these days people are seeing things in Facebook groups and they’ll come to us to say, ‘have you heard about this?’ We need to clarify this and do explainer articles on what the news [facts] is.’ He noted this had to draw heavily on information from official government and health sources. Respondents also noted that the general public need more digital literacy education as they often comment inappropriately on court stories, and don’t realise the consequences of their actions online.

A respondent who until recently worked at a commercial online news site noted the pressure of ‘eyeballs and clicks’. ‘A controversy that divided opinion was enough to be a story – when everyone’s divided as an audience, it becomes a big driver as traffic.’ He noted the focus was less about important news and more about ‘trivial matters because that’s what people were reading’ and that ‘user generated content and comments’ did not support truthful ‘narratives’.

There was also a strong focus from the majority of respondents noting that politicians share their ‘propaganda’ which half of the respondents also noted was at times ‘misinformation’. Respondents also noted that time constraints left little time to investigate political sources and media releases which became relied upon. Another respondent in Sydney noted verification had slowed down the work he does – ‘even the things that look convincing’ must be checked ‘given my understanding of the information ecosystems’.

Interventions and mitigation

The final area of the interviews focused on ideas about interventions to mitigate the impacts of mis- and disinformation. Results from the IFTF study found only 15 percent of surveyed journalists have taken part in any sort of training on how to combat the effects of false information (Carter Persen et al., 2019d). Journalists raised the challenges of finding the original source of links online, and the desire to have a specialist data journalist in each newsroom. The surveyed journalists noted they relied on ‘instinct’ as well as more traditional methods of fact-checking information, searching for multiple sources of confirmation on a particular claim, and talking to sources in person as standard practices that can help prevent the dissemination of false information. Surveyed journalists sought more resources to help them spot mis- and disinformation – including specific tools and training that could help them identify bots for example. They also requested guidelines for reporting on false information in order to prevent their reports from being counterproductive or doing harm; advice on operational and legal security; mental health resources accountability mechanisms; and improved media literacy throughout the education system.

The Australian survey asked journalists whether they felt they had adequate support and training to deal with mis- and disinformation. 14.1 percent of survey respondents said they have had adequate training and support, with the majority of the remaining respondents noting they prefer or really need more training and support. Similarly, to the IFTF study, the majority of the Australian respondents lacked the confidence to trace mis- and disinformation back to original sources and uncovering links to those sources. Education pathways such as University courses had equipped the respondents with ‘traditional’ fact checking methods as also noted in the IFTF results. However, rarely did the institutions equip journalists to monitor and verify information using online tools.

For on-the-job training, formal upskilling in monitoring and verification is rare, with only 11.8 percent of respondents having formal training provided by their employer, and of these, typically only three days or less per year was provided. Additionally, those who had reported they had experienced training, online monitoring and verification was rarely in detail. The one to one follow up interviews noted that training would be most beneficial if the tools could be built upon immediately in newsrooms, with support as required. Typical comments for those that had more detailed training responded that they felt overwhelmed and didn’t know where to begin once they went back to the newsroom. While results from the IFTF study noted respondents wanted more guidance on how to report and approach reporting on mis- and disinformation. Similarly, the Australia survey directly asked whether there were formal guidelines in newsrooms that covered issues such as the ‘tipping point’ (when to report on problematic content without doing more harm) and that only seven (7) percent of respondents had adequate guidance. Australian journalists called for an expert in advanced areas of tracking and reporting on mis- and disinformation campaigns – similar to the IFTF survey where respondents called for an expert such as a data journalist in each newsroom.

Summary and Recommendations

Only 14.1 percent of respondents noted they had received adequate training to deal with mis- and disinformation. An overwhelming majority of survey respondents, 75 percent, noted they ‘really need’, or would ‘prefer’ more training and support, with the remainder noting it was not relevant to their current role. Further applied action research is recommended so that journalists are immediately able to put training to use in real time, in real world scenarios. As noted in the interventions and mitigations section, the few journalists who had received training felt overwhelmed when they returned to their newsrooms. This is understandable as it is easy to lose confidence and proficiency in new skills as different scenarios and problematic content arise at different times, requiring tools or techniques journalists may not have practiced or implemented what they learned for a long period of time. The majority of respondents had either none, or very little detailed training in how to monitor the spread of mis- and disinformation and verify using online tools.

Respondents from both the Australian and IFTF survey noted the need for at least one expert in a newsroom to help write reports based on research. While this would take the form of an advanced expert in tracking mis- and disinformation campaigns and draw on data journalism skills, more journalists could be trained in the daily use of common monitoring tools which also allow for deeper insights and visual representation of the data. However, the expert or data journalists would need to be on hand to ensure the correct parameters and caveats are included.

Both surveys acknowledged the importance of collaboration. Respondents from the Australian survey show a positive interest in collaboration, which has arguably been rare among journalists who traditionally compete against each other in different newsrooms and even within the same organisations. The IFTF study included a collaboration intervention which showed a strong improvement in accuracy from journalists in recognising mis- and disinformation. Further research into such interventions in an Australian and Asia Pacific context is recommended.

The Australia survey and follow up interviews were the first iteration of the larger study in the region, with the next iteration is to focus on New Zealand, followed by the Pacific nations. A final summary and comparison for the region is recommended in order to implement solutions at scale and serve as a template for further research across APAC.

References

Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Tedros. (2020, February 15). Director General, World Health Organisation [Speech]. Munich Security Conference. Munich. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/munich-security-conference

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

Carter Persen, K.A., Joseff, K., Guilbeault D., Becker, JA., Woolley, SC. (2019a). Digital propaganda and the news: Exploring the effects of false information upon journalism. Executive summary. Institute for The Future, Digital Intelligence Lab.

Carter Persen, K.A., Joseff, K., Guilbeault D., Becker, J.A., Woolley, S.C. (2019b). Digital propaganda and the news: Exploring the effects of false information upon journalism. Brief One: False information in the current news environment. Institute for The Future, Digital Intelligence Lab.

Carter Persen, K.A., Joseff, K., Guilbeault D., Becker, JA., Woolley, SC. (2019c). Digital propaganda and the news: Exploring the effects of false information upon journalism. Brief Two: The effects of false information on journalism. Institute for The Future, Digital Intelligence Lab.

Carter Persen, KA., Joseff, K., Guilbeault D., Becker, J.A., Woolley, S.C. (2019d). Digital propaganda and the news: exploring the effects of false information upon journalism. Brief Three: Mitigating the negative impact of false information. Institute for The Future, Digital Intelligence Lab.

CoreData (2020): Report: UTS CMT Media Disinformation 2020. CoreData. Commissioned by First Draft Australia bureau, based at the Centre for Media Transition, University of Technology, Sydney

First Draft (2020) Our Mission. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/about/

Funke, D., (2019, April 25). Study: Journalists need help covering misinformation. Poynter Institute. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2019/study-journalists-need-help-covering-misinformation/

Helliker, Jackie (2020). Nielsen Digital Content Ratings. The Nielsen Company, LLC, US. https://www.nielsen.com/au/en/press-releases/2020/abc-news-websites-ranks-no-1/

Hine, C. (2015). The internet in ethnographies of the everyday. In Ethnography for the internet: Embedded, embodied and everyday (pp. 157–180). London: Bloomsbury Academic. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218900.ch-006

Kruger, A. L. (2019). Ahead of the e-curve: Leading global social media verification education from Asia in a 21st century mediascape. HKU Theses Online (HKUTO).

Marwick, A., Lewis, R. (2017, May 15). Media manipulation and disinformation online. Data & Society https://datasociety.net/library/media-manipulation-and-disinfo-online

Park, S., Fisher, C., Lee J.Y., McGuinness, K. (2020, July 7). COVID-19: Australian news and misinformation. News and Media Research Centre, University of Canberra. DOI 10.25916/5f04158db291a https://www.canberra.edu.au/research/faculty-research-centres/nmrc/research/COVID-19-australian-news-and-misinformation

The Public Interest Journalism Initiative, PIJI (2020). The Australian Newsroom Mapping Project by Public Interest Journalism Initiative. https://anmp.piji.com.au/

Richardson, N. (2017). Fake news and journalism education. Asia Pacific Media Educator. 27(1):1-9. doi:10.1177/1326365X17702268

Wardle, C. (2019, October 21). Information disorder: The techniques we saw in 2016 have evolved. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/information-disorder-the-techniques-we-saw-in-2016-have-evolved/

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017, September 29). Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-researc/168076277c

Wardle, C., Greason, G., Kerwin, J, Dias, N. (July 2018). Information disorder: The essential glossary. Harvard Kennedy School Shorenstein Centre on Media Politics and Policy. https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/infoDisorder_glossary.pdf?x46415

Warren, C. (2019, April 27) Australia just had its first social media election. Crikey. https://www.crikey.com.au/2019/05/27/social-media-2019-election/

About the authors

Anne Kruger was previously an anchor and journalist at CNN International, Bloomberg TV, and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Anne founded ongoing online news verification projects in Asia and consulted for UNESCO while an Assistant Professor of Practice and Head of Broadcast at the University of Hong Kong. She is currently Associate Professor and First Draft APAC Director. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Centre for Media Transition, University of Technology Sydney.

Email: Anne.kruger@uts.edu.au

Contact: +61 2 95143078

Lucinda Beaman is a senior researcher at First Draft Australia, previously a fact check editor at RMIT, University, Melbourne ABC Fact Check and The Conversation. She teaches in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Centre for Media Transition, University of Technology Sydney.

Email: beaman@uts.edu.au

Contact: +61 2 95143078

Monica Attard holds a Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Law and is an author and writer. She was awarded an Order of Australia for services to journalism and is winner of five Walkley Awards for excellence in journalism, including a gold Walkley. She is Head of Journalism, Acting Co-Director Centre for Media Transition. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney.

Email: Monica.attard@uts.edu.au

Contact: +61418274917