‘Time’, a modern folksong in the age of COVID

Diana Blom

Western Sydney University

Kevin Hanrahan

University of Nebraska

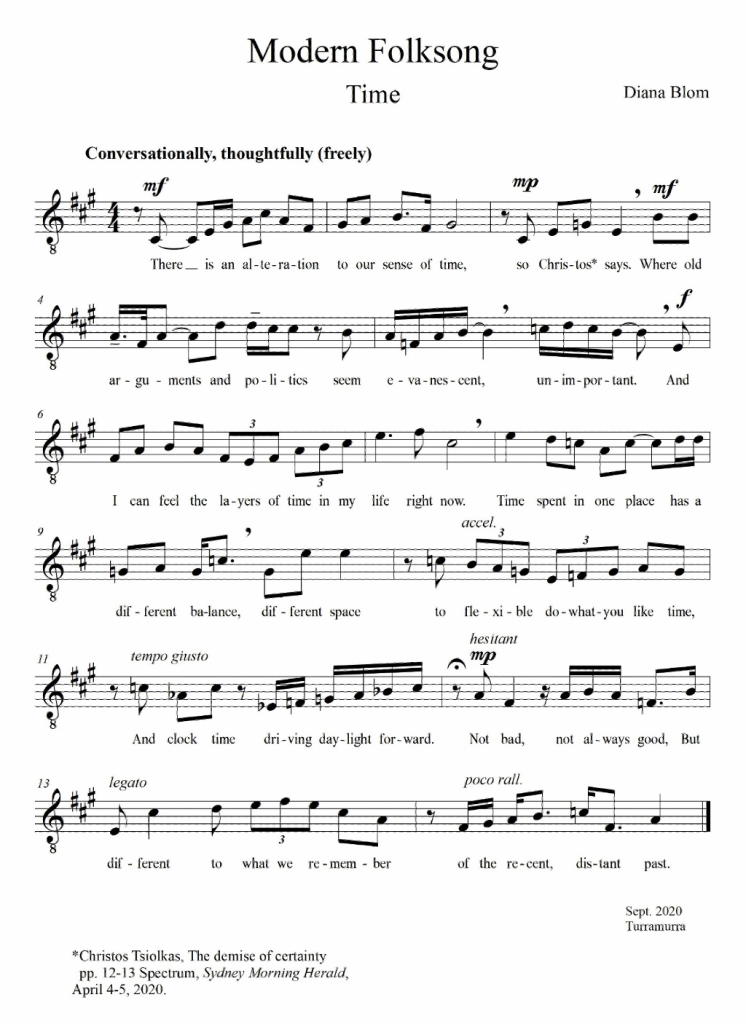

Musical responses to the COVID-19 pandemic year of 2020 range from parodies of existing popular tunes with revised words (Mandell, 2020) covering the early months of lockdown with its home schooling, social distancing, hygiene advice, quarantine and restrictions to movement. Artists responded to these restrictions in a variety of ways: online videoed performances; classical dancers at home dancing to classical music (Asprou, 2020); scientists translating the virus into melody (Reuters Staff, 2020); new popular songs (Fekadu, 2020); and new classical music (ABC, 2020). ‘Time’, one song from a set of four Modern Folksong for unaccompanied solo voice, composed in September 2020 during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, fits into the last response category. No live performance has taken place, and the songs are to be posted online, joining these other musical responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Modern Folksong set reflects the experience of living through the lockdown of the COVID pandemic in Sydney, Australia, where the composer, Diana Blom, lives. Lockdown was a time of unhappiness, isolation, loneliness, sorrow, illness and death for many. For performing artists, it was a time when live performance could not take place, with the performing arts possibly the industry most hard hit by the pandemic lockdowns. Hanrahan, the tenor, spent much of 2020 teaching singing at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, outside his institution in a courtyard, not a voice studio. But for other creative artists not engaged in live performing, 2020 was a period of reflection, a time to get work done, to write, to engage in big thinking and new ideas.

The four song texts of Modern Folksong were chosen from 2020 writings to capture this period of reflection and a range of moods from different writers. Bani McSpedden’s The COVIDIC Verses ‘The Good News’, a verse set, published in a Sydney newspaper, uses humour to tell of the realisation of missing friends, finding some have been neglected, reviewing one’s own soul and its neglect in favour of material things yet with now a chance to “wipe the slate clean” (2020). Juan Salazar’s text on Antarctica engages in big thinking, imaging how the five cities closely connected to Antarctica might come to embody values associated with Antarctica – ‘global co-operation, scientific research, ecological conservation’ – and in turn become ‘global custodians’ of the South Polar region. Robyn Boyce’s poem ‘Forgotten Fire’ (2020) reflects on how the horrors of, and recovery from, recent Australian bushfires have been swept aside in the news by the blanket of COVID-19 – ‘time warps and action ceases. The tapestry falls inwards as we spoilers lock down’.

The song, ‘Time’, draws on ideas in Christos Tsiolkas’ essay published in a Sydney newspaper, ‘The demise of certainty’ (Tsiolkas, 2020), and talks of how our sense of time has been altered with old arguments seeming ‘ephemeral and unimportant’ in the age of COVID. The music of ‘Time’ is reflective, thoughtful and conversational in style, which suits solo voice. Not a rollicking repeated stanza folk text but drawing the freer, reflective folksong tradition for solo voice into classical music as a meditation on our sense of now, during lockdown. There is a marriage between text, music and rhythmic figures and shapes. The triadic motives wander up and down as thought bubbles, with major to minor modal shifts catching different reflections like a mirror – ‘evanescent, unimportant – not bad, not always good’ – and chromatic harmonic colouring seeking to capture different experiences of time. The rhythm moves faster as thoughts tumble out, slowing down when considering what’s been said. The rhythm relaxes when time is flexible and pushes forward when clock time is ‘driving daylight forward’. Music and text join together to flicker back and forth as the writer ruminates on changing perspectives of time in the restricted environment of a lockdown.

The title Modern Folksong was chosen because solo voice is what folk singing is about but also because the texts tell stories of our time. So, is ‘Time’ a modern folksong? For Graeme Smith (2015) the Australian folk music movement:

“…promotes a wide variety of popular and vernacular musics, [yet] it still holds to an idea of a central core of a founding, fundamental folk music in Australia. This core is a body of songs understood as created by rural workers and white settlers in the nineteenth century, reflecting and documenting the lives of convicts, gold miners, shearers and the like” (p. 218-219)

Yet in his article on folksong definitions, Amann (1955) supports Smith’s broader view of what folk music is, that is:

… any song in any age was the product of an individual author with some poetic gift and sense for form … The social class from which an author came is unimportant (p. 102).

He finds anonymity of authorship is not required for a folksong. In terms of longevity of the song:

any song which caught the fancy of the people (people in the broadest sense of the word), and which was sung by many over a reasonably long period of time, should be called a folksong (p. 104).

While ‘Time’ and the Modern Folksong set are too recent to fit this last criteria, they do reflect the first. And in his ‘attempt to establish the conditions and reasons for pop’s political role’ (p. 50), Street’s (2006) essay comments on ‘how particular times and experiences become incorporated into the music’ (p. 53) – not folk music as such, but very much music reflecting, in this case, the politics of its time.

This is relevant for Modern Folksong text topics, their year of publication, and also the recording conditions of ‘Time’. Rehearsals took place via Zoom, possible with one voice, the recording made in Nebraska by Cameron Shoemaker and edited in Sydney by Noel Burgess. Singers for the other three songs of Modern Folksong will be recorded in different parts of the world – that’s the beauty and flexibility of the solo voice. The song texts don’t offer comfort as such to those living through the pandemic but illustrate one way the performing arts can survive and inspire our creativity to create music for these times. They also leave behind a set of musical stories of the 2020 COVID-19 experience of four people – modern folksongs.

References

ABC (2020, April 3). COVID-19 inspires some creative compositional responses ABC Classic. https://www.abc.net.au/classic/read-and-watch/news/compositions-during-covid-19/12119576

Amann, W.F. (1955) Folksong Definitions: A Critical Analysis Midwest Folklore, 5(2) Summer, pp. 101-105

Asprou, H. (2020, April 30). Paris Opera’s ballet dancers perform from bedrooms, bathrooms and kitchens in tribute to key workers, Classic FM Digital Radio. https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/periods-genres/ballet/dancers-film-enchanting-romeo-juliet-sequence/

Fekadu, M. (2020, May 4). 40 songs about the coronavirus pandemic. The Boston Globe. https://apnews.com/article/2a49e686206f00c6f74d5d132225bc4a

Johnson, S. (2020, March 24). A quarantine playlist to help you get through COVID-19 social distancing, Daily Herald. https://www.heraldextra.com/entertainment/music/a-quarantine-playlist-to-help-you-get-through-covid-19-social-distancing/collection_911b5f5a-2faf-552f-a20e-5b0330a2a2cd.html#1

Mandell, J. (2020, April 15). Top 10 Coronavirus song parody videos, New York Theater https://newyorktheater.me/2020/04/15/top-10-coronavirus-song-parody-videos/

McSpedden, B. (2020, August 1). The COVIDIC Verses ‘The Good News’, The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/life-and-relationships/the-covidic-verses-poetry-inspired-by-a-pandemic-20200719-p55dh7.html

Reuters Staff (2020, April 23). Coronavirus the musical: U.S. Scientists turn virus into melody to aid research, Science & Space. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-music-idUSKBN2222O7

Smith, G. (2015) Australian Folk Song: Sources, Singers and Styles, Musicology Australia, 37(2), 218-233, DOI: 10.1080/08145857.2015.1065549

Street, J. (2006). The pop star as politician: from Belafonte to Bono: From creativity to conscience. In I. Peddie (Ed.), The Resisting Music and Social Protest, (pp. 49-61). Ashgate.

Tsolkas, C. (2020, April 4-5). The demise of certainty, Spectrum, The Sydney Morning Herald, pp. 12-13.

About the authors

Diana Blom is a composer, pianist and academic whose research focuses on live performing/recording studio performing, Australian popular songs of the Vietnam War, online music in the time of COVID and tertiary performance. Published scores and CDs are released through Wirripang Pty. Ltd., Orpheus Music and Wai-te-Ata Press. Diana is co-author of Music Composition Toolbox (Science Press) a composition text. She is Associate Professor in Music at Western Sydney University.

Email: d.blom@westernsydney.edu.au

Kevin Hanrahan

Associate Professor of Voice & Voice Pedagogy

University of Nebraska

https://arts.unl.edu/music/faculty/kevin-hanrahan

Email: khanrahan2@unl.edu