Not Unprecedented: Australia’s COVID-19 Archives

James Gourley

Western Sydney University

Abstract

This article makes the case for the liminality of Australia’s COVID-19 epidemic. It acknowledges the distressing loss of life and periods of significant societal disruption and contrasts this with the relative success Australia has had in being free from unrestrained contagion. The liminality of Australia’s COVID-19 experience is particularly discernible in the diversity of affective consequences the pandemic has had. In documenting elements of this liminality, the article reads various ‘citizen writing’ repositories, which it frames as Australia’s emergent COVID-19 archives. These archives – read as texts – exemplify the diverse affective experience Australians have had of COVID-19. It shows how Australians have experienced much grief, anxiety and fear during COVID-19; but at the same time, Australia’s COVID-19 archives reveals other emotions just as consistently: such as solidarity, humour, and care.

Writing from within a pandemic

As at June 28 2021, the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard recorded a total of more than 180 million infections and 3.9 million deaths around the globe. These numbers are immense and distressing, and yet do very little to communicate the ongoing, yet unequal, impact this pandemic has had on people around the world. In Australia, the question of how severely the pandemic has impacted the nation and its citizens is complicated. More than 900 Australians have died from COVID-19, and almost 30,000 Australians have suffered from the disease (Department of Health: Australian Government, 2021). By many economic measures, the impact of the pandemic has been severe (See, for instance, O’Sullivan, Rahamathulla & Pawar, 2020). And while the nation experienced particular pressures in March and April 2020, and during its ‘second wave’ (focused in Victoria from late June to mid-September 2020), Australia has been largely removed from the terrible impacts of widespread infections seen in other nations. As such, Australia’s experience of the COVID-19 pandemic has been liminal: in some places and for some groups the impact has been severe; for others, the impact has been relatively limited. Further, while Australia and Australians have been relatively less impacted by the COVID-19 disease thus far, the nation remains firmly within the regime of pandemic. This pandemic governance has affective consequences even in spite of the relatively limited spread of the disease itself. In documenting elements of this liminality, this article turns to forms of ‘citizen writing’ produced in 2020 which are particularly inclined to describe the diverse affective experiences of the pandemic Australians have had.

As humanities scholars have consistently observed, pandemics produce vast archives, and the literature which is part of this archives provides the means to understand public perceptions of the pandemic, its emotional impacts, and the changing view a society holds of a pandemic as time passes. 1 While this article rejects the characterisation of the COVID-19 pandemic as ‘unprecedented’ (and more on this below), its focus on series of ‘born-digital’ textual reflections on the pandemic does require acknowledgement that this pandemic is not exactly like those pandemics before it. This is the first global pandemic in which digital and social media proliferation has meant that the majority of citizens are able to write and publish their feelings about these events. So, while in previous pandemics an archive of private writing documenting the affective experience was produced and remained dispersed, during COVID-19 social and digital medial platforms have facilitated the collecting and publication of these private reflections. This constitutes a significant transformation, and this article reads Australian COVID-19 writing so as to understand the diverse and liminal experience of COVID-19 Australians have had. The texts and archives discussed below are selected for their contemporary prominence, and for their born-digital, shareable nature. Doubtless, there are other archives – both digital and otherwise – that other scholars will address. My interest in these particular archives and texts is because of the personal, and yet diverse, reflections they make on the question of Australia’s liminal experience of COVID-19; both in and out of the global pandemic simultaneously.

One of the considerable challenges scholars writing on COVID-19 acknowledge is posed by writing about a pandemic during a pandemic is the inevitability of one’s perspective being located and produced from ‘within’ the pandemic and the limitations this may cause. The Australian writing this article examines has this constrained perspective redoubled: not only are these texts produced from within the temporal timespan of the COVID-19 pandemic, but they are touched by the liminality of Australia’s COVID-19 experience. That this writing is produced from this particular perspective has its ironies, not the least of which is the historical and real role of borders as biosecurity infrastructure, and recent Australian history in which the ‘border’ has become a coercive political imaginary (Alison Bashford’s thinking is of particular use here. See Bashford, 2016; Bashford & Hooker, 2002; see also Brett Neilson’s essay published in this edition) .

Historical comparison provides the means to look beyond the present: For instance, the Spanish Flu (1918-1920) killed between 21 million and 50 million people. Closer to the present, the two largest respiratory epidemics of the 20th century, the ‘Asian Flu’ of the late 50s and the Hong Kong flu of the late 60s, both killed around one million people. The HIV/AIDs epidemic has killed between 25 and 35 million people in the last 40 years.

Which is all to say that the pervasive idea that the COVID-19 pandemic is ‘unprecedented’ is not correct. 2 This viewpoint – promulgated by many across a variety of domains – can instantiate and replicate an imperialist and anti-historical worldview which perceives any impact upon western privilege, health and security as without precedent. 3 In fact, biology researchers, for instance, have provided consistent warning of the likelihood of a pandemic event as a consequence of zoonosis for quite some time. Andreas Malm, an historian of economics, is particularly insistent on this point:

By 2019, the scientific literature referred habitually to the fact that ‘infectious diseases are emerging globally at an unprecedented rate’, the share made up of zoonoses estimated at between two thirds and three fourths, increasing to nearly 100 per cent for pandemics (Malm, 2020).

Clearly then, just as the COVID-19 pandemic is not unprecedented, it is also reasonable to say that there were significant and consistent warnings of a pandemic prior to COVID-19’s proliferation in 2020. And while an event’s occurrence after warnings does not, of itself, confirm that the event is without precedent, warnings speak to a broader historical purview which understands pandemics as a terrible, but regularly encountered experience humans have faced for thousands of years.

Despite the relatively limited consequences for various parts of Australia, this article insists upon the impact of COVID-19 and seeks to quantify its affective impact upon the nation. It does so by illustrating how individual documentation of the emotional impact of epidemics has evolved in Australia in 2020. The rise of personal digital media platforms means that COVID-19 is the first global pandemic in which the majority of the population is able to record their experiences for posterity. This article surveys prominent Australian digital archives that were established early in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so it shows how Australians have experienced much grief, anxiety and fear during COVID-19; but at the same time, Australia’s COVID-19 archives reveals other emotions just as consistently such as solidarity, humour, and care (cf. Hobbins, 2020).

Because of the challenge of writing on the COVID-19 pandemic from in its midst, the intentions of this article are discreet. I acknowledge here Sari Altschuler’s and Priscilla Wald’s (2020) evocation of ‘narrative and epistemological humility’ as a scholarly necessity in the current circumstances. This narrative and epistemological humility is performed in the multiple and diverse Australian ‘publics’ and their texts that this article surveys. While the texts discussed by the article are by no means the extent of public social responses to COVID-19, they do provide the means for a narrative impression to be made of COVID-19 and its impact in Australia. This impression is contingent, and specifically linked to the time in which the texts are written. As vaccine distribution impends in Australia, we anticipate the COVID-19 pandemic being past. The narratives discussed below reiterate that this past-ness is illusory, and that the COVID-19 pandemic and its archive will be important for many presents to come.

State Library of New South Wales’ Social Media Archive

The State Library of New South Wales’ (SLNSW) Social Media Archive is a sophisticated set of tools that allows a reader to look at the narratives and emotions of New South Wales’ social media users. The SLNSW Archive scrapes and assembles social and other media posts relating to, or produced within, New South Wales. The archived texts are categorised by ‘activity’ (understood as ‘representing different aspects of life in New South Wales’) and ‘mediatype’ (a broad categorisation of media). After categorisation, the SLNSW Archive then provides a layer of interpretation: the Archive is assessed for its emotional content. Posts are classified as displaying an emotion (using Parrott’s hierarchy of emotions) if they include one or more ‘emotion terms’; essentially a list of words pertaining to each emotion (State Library of New South Wales, 2021a). This section reads the SLNSW chronologically from the beginning of 2020 over the early period in which COVID-19 emerged, comparing social media text and the emotional content it reveals. The intention here is to trace Australia’s movement into pandemic time, and the emotions Australia’s entrance into the pandemic prompted.

As 2020 commences, Australia was in the grip of the Black Summer bushfires, and its emotions (as interpreted by the Archive’s ‘Emotion Detection system’) are inclined to sadness. 4 The incipient COVID-19 pandemic does not register in the Social Media Archive, and only a very small number of news stories (eight) pertaining to the developing pandemic are published. Despite this absence, events leading to the COVID-19 pandemic are underway and other parts of the world are already significantly affected by the pandemic. A cluster of ‘pneumonia-type’ infections is expanding in Wuhan, China. World Health Organisation (WHO) procedures are underway, with a first ‘Disease Outbreak News report’ issued on January 5, 2021 by the WHO. The first time there is sufficient volume of social media posts for the Social Media Archive to register the existence of COVID-19-related activity is in the week ending January 26, 2020. Volume is very small, however, and the emotions the news elicits is not clear.

Tellingly, the Social Media Archive registers a significant increase in activity in the week ending February 2, 2020. This is the first time in 2020 that the ‘health’ activity is in the top 10 most-referred-to activities. 5 This volume increase coincides with the WHO’s January 30, 2020, declaration that the novel coronavirus situation constituted a ‘public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC)’ (WHO, 2021). (This declaration is a precursor to the declaration of a pandemic.) At this point, the WHO reports 98 cases outside of China, with four countries exhibiting human-to-human transmission. After this, the coronavirus recedes into the Social Media Archive’s background; a regular feature, but never dominant, its emotional impact on New South Wales social media users not yet significant enough to really register on the ‘Emotion Detection system’.

In March 2020, this begins to change. The Australian government began treating COVID-19 as a pandemic from the end of February, and on March 13 very significant quarantine measures were put in place, with implementation commencing on March 16. 6 From the point of view of government, Australia is now ‘in’ the pandemic, and it is beginning to catch New South Wales’ attention. In the week ending March 8, ‘panic’ is the seventh most used keyword on social media, with 2,578 recorded uses. The emergent emotional response to impending COVID-19 impact in New South Wales is toilet paper, with reporting on ‘panic buying’ of toilet paper and resultant shortages a feature of this week’s news. By the week ending March 22, 2020, COVID-19 dominates social media; ‘health’ is now the second-most addressed ‘activity’, surpassed only by politics (which is the consistent and unchallengeable number one). 7 Australia’s distress and uncertainty is manifest; in these health-focused social media posts, there is really only one topic: a proliferation of COVID-19 news, including plaintive hashtags like #Lockdownaustralia, #FlattenTheCurve, #ShutTheSchools and #newstart.

#Lockdownaustralia and variants (#lockusdown being a particularly interesting variation), indicate a number of divergent emotional responses. For instance, it seems clear that the prevalence of these hashtags indicates a fear of impending catastrophe as COVID-19 moved through communities. #lockusdown is particularly clear here, as it pleads for authorities to act to secure the health of the nation. It is also possible, in contrast, to read the prevalence of these hashtags as evidence of civic spirit and responsibility; by acknowledging the necessity of short-term impingements upon human rights of movement and association, Australian social media users are indicating their principled acquiescence in the face of these changes to their rights, and a thoughtful understanding of the immensity of the COVID-19 challenge. At the same time, however, the call to #lockusdown can be seen as a desperate – and privileged – call to be sequestered away from the pandemic, for it to remain outside Australia, and outside the self. In a sense, then, these early responses anticipate and instantiate the emphasis on borders and policing that are dominant and have endured throughout the world as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. They also provide a foundation for Australia’s liminal experience of COVID-19.

Where hashtags focused on quarantine measures are able to be interpreted as indicative of fear of the virus as well as civic goodwill in assessing governmental and public health responses, #newstart and other social-welfare-focused posting is less overtly positive. Or to be more accurate, the emotional implications are less clear. The proliferation of social media posts pertaining to welfare and governmental support is a consequence of the immense job losses the Australian economy sustained from the second half of March 2020 onwards. The federal government announces its ‘JobKeeker’ package on the March 30, itself registering a significant set of responses under #jobseeker. The prevalence of this material indicates three things: the very real need for welfare support experienced by many Australians during this period; broad endorsement (and thankfulness) for the government’s policy; and civic solidarity with those suddenly impacted by job losses.

What is clear is that by the middle-to-end of March 2020, Australia is ‘inside’ the COVID-19 pandemic, despite how strenuously many of us might have wished we were not. At this point in time, the SLNSW Archive becomes less useful because its large volume provides less opportunity for meaningful differentiation week-on-week and month-on-month during pandemic time. Thus, this article now turns to one particular hashtag as a means to secure particular insight into Australia’s experience ‘in’ the pandemic from late March 2020 onwards.

#covidstreetarchive

The historian of medicine and professional historian, Peter Hobbins, has been at the forefront of Australian scholarly efforts to ensure a citizen-led digital archive of the COVID-19 experience is established and recorded for posterity. Hobbins has been particularly intentional in the archives he has established, curated and drawn others’ attention to, and his emphasis on citizen-led rather than scholarly archives facilitate further access into the emotional consequences of COVID-19 for Australians. Reflecting upon his instigation and development of the hashtag #covidstreetarchive, he notes that COVID-19 collections-in-progress remain predominantly hard-copy focused:

What unites [these] initiatives – whether at national, state or local level – is their surprisingly nineteenth-century approach to collecting Covid-19’ (Hobbins, 2020).

#covidstreetarchive is one attempt to modify the traditional approaches which have proliferated in Australia’s COVID-19 Archive so far. In contrast, Hobbins offers #covidstreetarchive, which, while ‘neither systematic nor endorsed by the collecting institutions [he] wilfully tagged’, seeks to draw Australia’s COVID-19 archive into the 21st century, by establishing an online, image- and impression-focused personal account of the emotional reality of life in Australia during the period of COVID-19 restrictions. And while a hashtag doesn’t meet all of Hobbins’ own archival desires which, he suggests necessitates:

… capturing metadata [and facilitating] interpretive longevity’ so as to avoid ‘electronic ephemerality’), #covidstreetarchive does facilitate the accretive development of digital archives for others to read, reflect upon and interpret during the pandemic and after (Hobbins, 2020).

Tellingly, perhaps, before Hobbins activates #covidstreetarchive, his historical training means he already rejects the idea that COVID-19 is unprecedented. On March 20, 2020 he tweets: ‘indeed, for the first time in my historical career I feel like the world I live in is uncannily like a period that I’ve studied …’. Four days later, Hobbins establishes the hashtag, writing: ‘Inspired by Bruce Baskerville at #UWA I’m starting to document the #covidstreetarchive – hopefully with enough metadata to allow my feed (and bad photos) to be scraped.’ The main image attached reflects the uncertainty of the time.

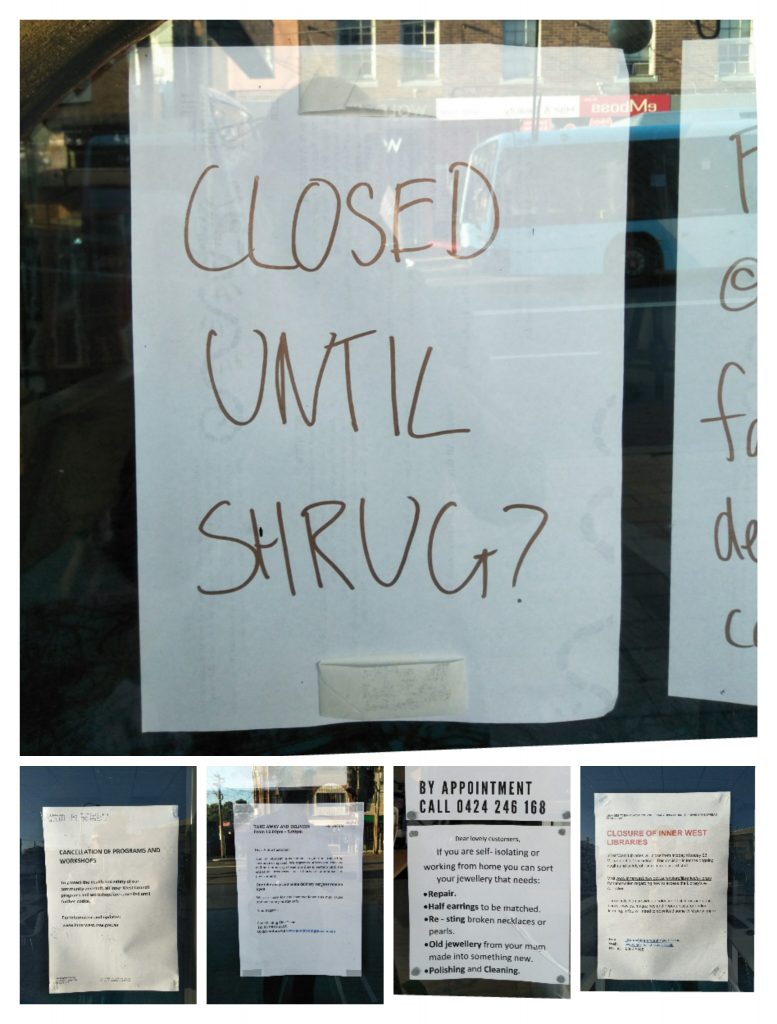

At its commencement, #covidstreetarchive is Hobbins’ alone, and documents his walks through the streets of the Inner West suburbs of Sydney, archiving what he terms ‘pandemic ephemera’. Hobbins is anxiously earnest, suggesting the pressure of those early days as lockdowns were put in place and uncertainty dominated: ‘I will go out tonight with a decent camera, but who knows how longer we can walk the streets? This is Marrickville Road, Dulwich Hill #covidstreetarchive’. This anxiety can also be understood as an emotional manifestation of the liminality of those March days: was Australia in the pandemic or out of it? How catastrophic would the impact of COVID-19 be? He tweets regularly, with a few other users contributing and/or discussing the digital methodologies available to secure the hashtag over time. Hobbins is sensitive to the emotional impacts of the NSW quarantine, posting tweets such as the following:

Krisi’s and Rachid’s story exemplies, I think, the early Sydney experience of COVID-19 quarantine; considerable uncertainty, sobering stories of dislocation and separation, alongside the emergence of a hitherto submerged solidarity among communities across the city.

Within a week #covidstreetarchive has contributions from South Australia, Queensland, regional New South Wales and New Zealand, while remaining primarily located in Sydney’s inner west. One regular contributor, ‘D S B’ (@david_browne), makes a series of insightful posts, including a set that document the emergence of a conspiracy theory (still enduring today), which suggests that COVID-19 is caused by the 5G network rollout.

Thinking charitably, the belief that COVID-19 is caused by 5G needs to be understood as a symptom of the anxiety the pandemic produced. This is not, however, to disregard the fact that this conspiracy theory did not commence with COVID-19, and also to acknowledge that assessing conspiracy thinking is never as simple as explaining the narrative away as ignorant (see Jane & Fleming, 2014). Despite this, D S B’s tweets illustrate the considerable pressure of this period in New South Wales, and the diverse affective responses it produced. While #covidstreetarchive presents itself as a sort of academic history in action, at its moments of most diverse participation, the hashtag is able to gesture toward the emotional complexity of COVID-19 in Sydney in 2020.

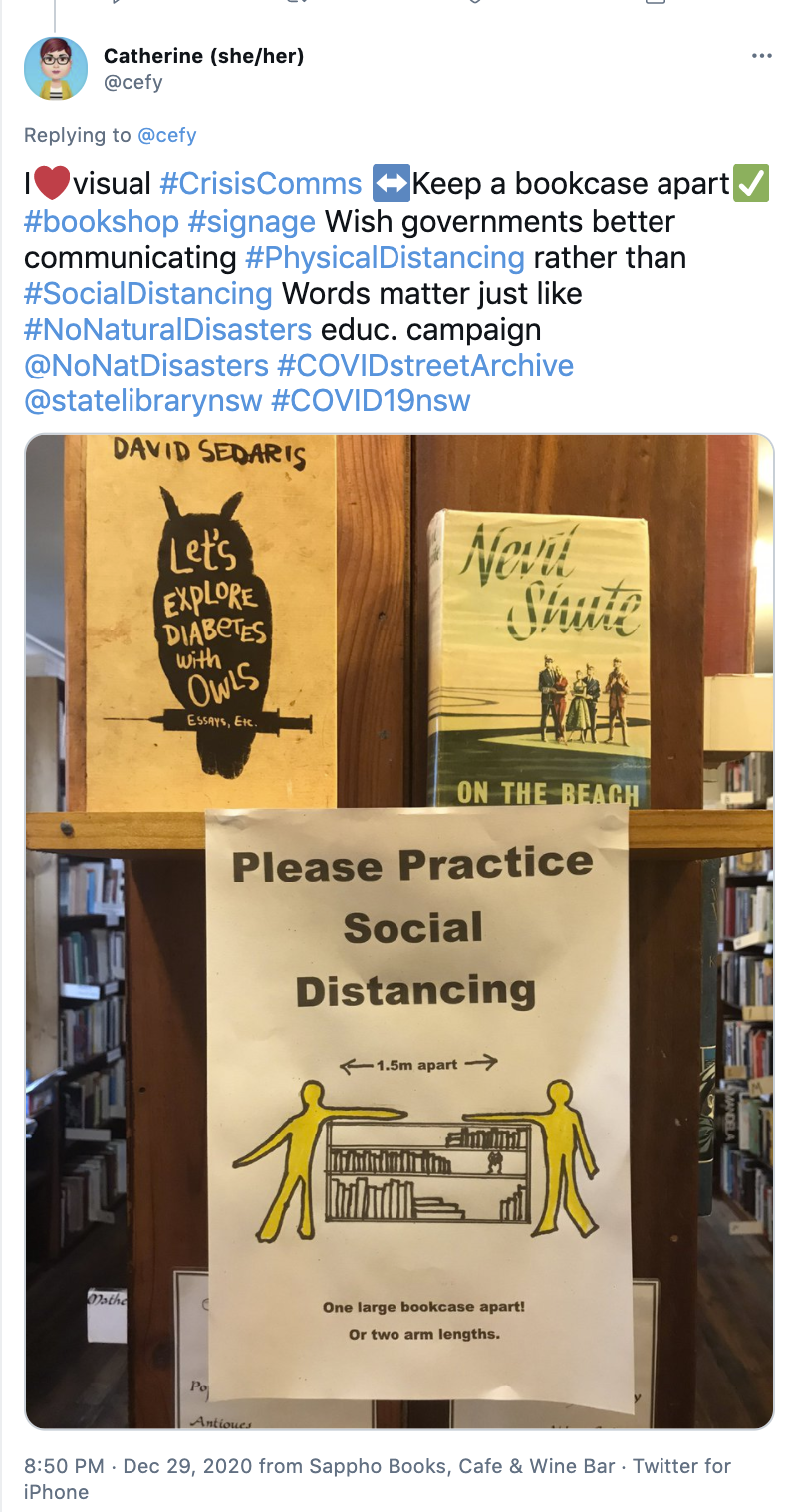

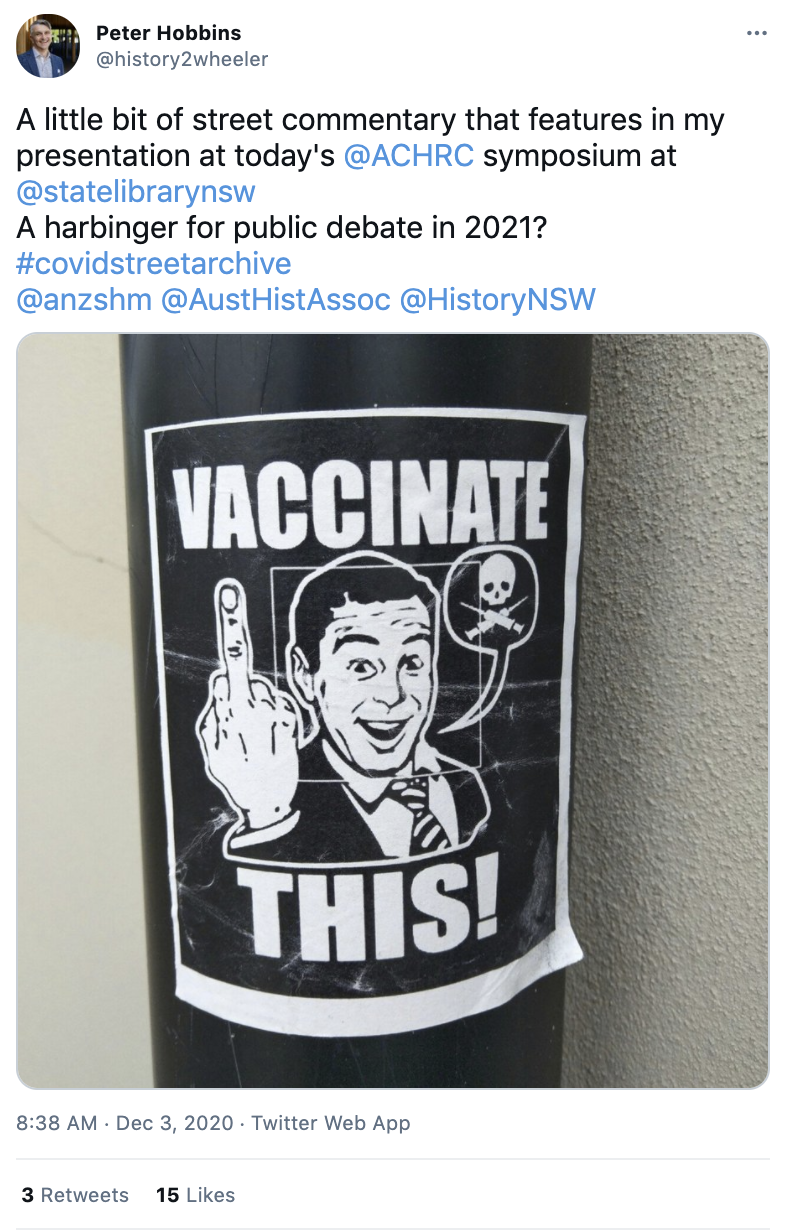

In its latest manifestation, #covidstreetarchive has also begun to function as a proxy-hashtag for academic work pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic and its archive. Hobbins’ own scholarly discussion of #covidstreetarchive is now accessible via the hashtag itself. And use of the hashtag has diminished from the flurry of activity in the first half of 2020, Hobbins and others have turned their focus more resolutely to the political, with the images below being the last two tweets from #covidstreetarchive.

The Diary Files

The Diary Files, a public writing project run in partnership between ABC Radio Sydney and the State Library of New South Wales, offers a diary-like forum for Australians to reflect upon the ‘extraordinary times’ of 2020, and is framed as ‘a time capsule that captures this moment in time’ (ABC Radio Sydney, 2021). Contributors write and post c. 300-word submissions, which are intended to reflect the everyday and the personal. The Diary Files makes explicit that COVID-19 has emotional as well as physical consequences, and that Australian’s diverse emotional experiences are of particular interest:

Everyone has a story to tell. No one looks out over the bridge of your nose, but you. What you see is yours alone…

The Diary Files collects vignettes from the everyday lives of the people of NSW and beyond. Tell us what you see, what you feel. Write about your morning coffee. Write about what you wish you said to her but never did.

You don’t need to be a writer to write here. We’re not after Sophocles or Virginia Woolf. You can write 20 words or write 300, submit anonymously or use your name. What did you have for breakfast, and what keeps you up at night? If you can read, you can write. Please write to us. Your words will become part of The Diary Files. Over to you (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b).

The Diary Files documents #NSWatHome, ‘This Moment in Time, [the ABC’s] project to capture our experiences and thoughts during the Covid 19 period’ (ABC Radio Sydney, 2021). The major principle of The Diary Files is that 2020 is a fraught and emotional time and that ‘citizen writing’ produced within that moment by diverse citizens provides insight into the public’s experience and an opportunity for support, reflection and growth for those who read the submissions. The Diary Files is apparently intended to record the emotions of the time, and also to provide an emotional release for those who do the writing.

As with other digital social writing projects pertaining to COVID-19, a series of tools is provided to understand the overall scope of the submissions. The Diary Files ‘dashboard’ provides three categories of information: location of submissions (by state, where NSW is the dominant contributor; and by postcode, where Greater Sydney is the greatest contributor); age of contributor (with 10-15 year olds making the majority of submissions); and regularly-used words. As at 5 February 2021, of 1110 submissions, 934 used the word ‘time’, 850 ‘school’, 794 ‘home’, 722 ‘people’, and 721 ‘COVID’. The pandemic and its impacts are clearly the focus of the majority of submissions.

In considering The Diary Files, this article turns to two different groups of contributions. The first, written by regular and repeat contributors, reflect upon their personal experience of the COVID-19 pandemic in an extended fashion. These contributions are notable for their sophistication, and for their hermetic literary stylings. They largely replicate the experiences and viewpoints expressed in the SLNSW Social Media Archive and #covidstreetarchive. The second group of submissions is potentially at odds with thinking on the impact of COVID-19 in Australia: eight submissions from a high school English class in Mudgee posted on August 7, 2020. This small group of submissions (seven from students and one from their teacher) is disparate, and yet provides significant insight into the emotional consequences the pandemic has produced for regional Australians: a group who in 2020 often experienced a particularly liminal COVID-19 pandemic, existing on the border between being inside the pandemic and outside it. (Speaking broadly, regional Australia has experienced a largely limited health impact, but with more significant impacts in terms of freedom of movement, economic consequences and so on).

In reading The Diary Files, it is clear that the most regular type of submission was written by a school-age child, reflecting on the impact of COVID-19. Apart from those submissions written by school-age children (one presumes often as part of creative writing training at school), a significant feature of The Diary Files is the commitment of some contributors to the project. Of particular note are the twelve submissions made by ‘Anastasia’ and the ten made by ‘Vanessa W’. Both these contributors provide a sustained commentary on their personal emotional experience of COVID-19.

For piano teacher, ‘Vanessa W’, the major theme of her submissions is disruption, both personal and societal (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). COVID-19 enters into New South Wales in time where disruption is already occurring; the 2019/20 bushfires caused significant devastation. ‘Having begun the year with bushfires, smoke and heat, we are probably soon to be locked down. What a year.’ And as the virus proliferates, in Australia and around the world, ‘Vanessa W’ communicates a considerable shock at this second crisis. Change is the major feature: inability to travel to a garden home in Bowral, yoga lessons hastily moved online, doctors’ appointments via telephone, anticipated events cancelled (‘Patti Smith and her band at the Enmore …’). Then greater disruption: work suspended, a birthday celebration deferred, listlessness in the face of no work. The natural world provides ‘Vanessa W’ with solace. A lemon tree in Bowral which survived the summer heat without water (‘we bucket it each day we are here’) provides reassurance, and gardening contributes simple joys: ‘our backyard continues to delight and surprise in our first year here.’ This solace is not a distraction, however, with the disruptions of COVID-19 always near to mind: ‘The sun is glistening all across the ocean. Kookaburras chorus. It could be summer. I enjoy the salmon sunset and for a moment forget about COVID making domestic violence escalate all across New South Wales.’

For ‘Anastasia’, a ‘60-year-old (soon to be 61) retired teacher living on her own’ emotional solace is not so readily available. Whereas ‘Vanessa W’ begins writing her contributions to The Diary Files as the pandemic commences, ‘Anastasia’ starts writing at the end of May, and her contributions directly seek to respond to an emotional change the pandemic has prompted: ‘I felt buoyant till Thursday May 14. On that day my mood changed and I don’t know why. I don’t know what triggered it. I had a wonderful year planned.’ ‘Anastasia’ describes the many community links she has – neighbours, family, two French conversation partners. And while this community is important, the major theme of Anastasia’s contributions is how community is fragmented. This is not all related to COVID-19, with real estate developers’ plans to subdivide and develop properties in the neighbourhood a particular manifestation of this fragmentation. But COVID-19 has created additional distance, and it has an emotional impact on ‘Anastasia’: ‘The thing I miss the most is the touch of another human being. Touching elbows is no substitute for a kiss on the cheek.’

The individual reflections of ‘Vanessa W’ and ‘Anastasia’ provide insight but are marked by a particular solemnity. This solemnity disposes their reflection to the ‘serious’, and the emotional content reflects this. In contrast, the group of Mudgee high school students (‘Connor Van Reason’, age 15, ‘unique’ (17), ‘kobie close’ (16), ‘Hilary’ (15), ‘Ethan’ (16), ‘Lachlan’ (16), ‘Mia’ (16)) and their teacher, ‘Kezsah’, present a diversity of reflections upon COVID-19 that are less controlled by the constraints of the citizen-writing epistolary form. Instead, many writers in the class produce submissions that push against the accepted boundaries of the form, extending the possibilities of The Diary Files.

As Kezsah recounts in explaining the exercise the students have been tasked with: ‘Well here I am… Period 8 Friday afternoon, in the computer lab, trying to encourage a group of elite Year 10 students to take on the ‘The Diary Files’ and demonstrate their prowess with a keyboard’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). ‘Kezsah’s’ submission – couched ironically – makes a judgment on her student’s responses which, while understandable, I don’t believe is entirely warranted. In reflecting upon the equilibrium of the everyday in spite of the disruptions COVID-19 has affected (‘Everyone talks about how COVID19 has changed the world…Same [sic] things will always stay the same regardless of war, plague or natural disaster.’ [State Library of New South Wales, 2021b].), Kezsah writes:

Some things never change. Young adults, teetering on the edge of a new world, are all things. They are children. They are adults. They are hopeful and they are hopeless. They hold the future in their hands but feel no responsibility. They mock and condemn their predecessors, making ‘Karen’ into an insult, with no comprehension of the extraordinary power they possess to control the world with their words.

…and here they are, playing computer games instead of recording it all for the future generations. Such a shame. (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b).

While I sympathise with Kezsah’s frustration (‘Period 8 Friday afternoon’ can’t be the most propitious time for creative writing!), her students’ submissions deliver on a range of fronts and in doing so indicate that, in fact, her students are able to comprehend and employ ‘the extraordinary power they possess to control the world with their words.’ This is a testament to Kezsah’s lesson that she does not perceive. Kezsah also points to a particular attribute of adolescence that makes her year 10 English class particularly well placed to reflect upon the liminal reality of COVID-19. That is, these students’ lives are regularly lived on a variety of borders – in Kezsah’s terms this is between childhood and adulthood, hope and hopelessness, power and powerlessness. We might add some additional borders these young adults are asked to straddle – between freedom and control, between self-determination and submission, between suburban life and rural life, sometimes in pandemic time and sometimes out of it.

Of the seven student submissions, three are speculative (‘Connor Van Reason’, ‘kobie close’, ‘Mia’) harnessing various storytelling forms to tell stories of uncertainty and change. Each of these submissions includes a moment of revelation. In Connor Van Reason’s Frankenstein-inspired story, neural engineering facilitates the pursuit of revenge against unnamed enemies. kobie close’s story intertwines two tales of redemption: the narrating voice, who owes thanks to a ‘mysterious stranger who helped me out of my smashed car, just before it exploded’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). In an aborted interaction, the ‘mysterious stranger’ provides their own gratitude for a moment of redemption: ‘I am deeply indebted to you. The night of your car accident, I was on my way to rob a jewellery store. Saving your life brought things back in perspective. I now live an honest life, thanks to you. God bless you!’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). Mia’s submissions recounts friends ‘messing around with a Ouija board one night’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). The spirit of ‘a 10-year-old boy who had died on the property in the 1800s and was buried there’ returns, frightening the group out of apathy (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). While it is not necessary to push the point too far, it is possible to see these three speculative submissions as pertaining more closely to COVID-19 than Kezsah presumes.

The four remaining submissions cleave more closely to the task, providing personal accounts of the everyday in a time when the concept of normality is under much pressure. For Hilary, this amounts to a recount of her day and its simple pleasures: ‘It is currently 3:02 pm, and our school finishes at 3:25 pm so I get to go home soon. I have to catch the bus home, so I will get home at 4:16. But then I can have a hot shower, which is good because it is cold outside’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). In a similar mode, Lachlan takes a longer view to the task, specifically addressing the impact COVID-19 has had on him in the past and the present:

My life has been pretty great so far and even the bush fires and the pandemic haven;t [sic] affected my life drastically. […] Lock down did end ages ago but I feel like for some people the long-term affects [sic] will stay with them for a long time. I’ve seen this firsthand and do feel sympathy for them because I for some reason am not in their situation.

[…]

Back to now though. Recently I’ve had trouble with certain social aspects of schooling and I’ve had to re-access [sic] where I stand. I feel like ever since the lock down people’s moods and personalities have altered. Although I just have to accept that there’s nothing in the world I can do. On top of this lately I’ve had my mind on one person in particular. Yeah you know what I mean😁’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b).

As with the submissions discussed above, Lachlan is able to communicate the inescapable everyday-ness of his experience of a pandemic. What Lachlan’s submission also communicates clearly is the commitment to solidarity which has been a consistent feature of COVID-19 in Australia.

The final two submissions are especially notable for their efforts to destabilise the assigned task, and thus destabilising a coherent or total understanding of what the COVID-19 experience might be for anyone. For ‘unique’, the only writer to adopt an overt pen name in completing the task, the challenge comes precisely in the assumption that their experience might be unique: ‘[e]veryone has something to write in their diary while here i am still thinking what to write’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). unique detaches themselves from the specifics of the task, instead asking how reasonable the task is. The question is put implicitly: is my experience unique? ‘I mean, this day is not really bad and not really good’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). In unique’s equivocation, they point to the liminal and constantly changing reality of life in COVID-19. While unique may demur from the idea that their experience is unique, it does not discount the insight their reflections develop. unique reflects upon the simple pleasures that are the very fabric of the everyday: ‘Me and my friends just played Uno in the library at lunch and that’s the enjoyable thing i did today. […] i really love walking and i’m thinking to just walk from school to home’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). And toward the end of the submission, unique reveals much that conditions their reflection:

Well, maybe if it stops raining then i can just walk while listening to music is the best thing that i’m doing everyday. I love music so much. I listen to music for like 2 hours before i sleep because that can make my anxiety down and feel so good everyday. I also pray before i sleep of course. Nope, Actually when i just remember to pray that’s just when i prayed. (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b).

There is much to unique’s submission; intimations of joy and satisfaction intermingle with specific references to anxiety and consternation. I don’t think the submission provides any evidence to link any of these experiences or affects directly to COVID-19: but what began as a submission directly undermining the validity of the exercise ends up endorsing it because of its commitment to the task and its engagement with the serious task of thinking about and describing affective experience.

In contrast, ‘Ethan’ is clearly ambivalent about COVID-19’s consequence: ‘Life in my town has been relatively unchanged since the end of the unprecedented isolation schooling, everything has almost gone back to normal’ (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b). Continuity and change jostle, with the experiential reality of school shining through:

Finally, I could get to learning! No more unprecedented challenges, no more unprecedented hurdles, no more unprecedented times. However, we all know that in unprecedented times, unprecedented issues will always follow and spring up in an unprecedented fashion. I am writing this and am only just seeing how the word count has sprung up in unprecedented time. An unprecedented thank you for reading. (State Library of New South Wales, 2021b)

‘Ethan’ subverts the pedagogical task at hand. And yet in doing so, his ironic distance from the task of reflecting upon the pandemic illustrate the diversity of responses possible. The response Ethan crafts undermines any possible certainty once might claim about uniformity of experience and destabilises the assumption that a global catastrophe necessarily produces negative responses. In fact, Ethan’s response indicates a determined humour and stoicism in the face of a particularly challenging experience which is shared with many of his classmates. The Mudgee reflections document the diversity of emotional experiences of one English class in one regional town of New South Wales, while playfully undermining the seriousness of the task and the gravity of COVID-19. These citizen writing texts are sophisticated and provide deep insight into the liminality of COVID-19 in Australia.

Conclusion

Many of the citizen writing texts surveyed in this article make much of the apparently unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. And yet, as ‘Ethan’ and other writers discussed above point out, adherence to an understanding of COVID-19 as unprecedented is the major ground for a particularly conventional and inward focused response to the pandemic. The COVID-19 Archive evaluated in this article is voluminous; a product of the rise of citizen writing and social media both. 8 As pandemic time recedes or mutates in 2021 and beyond, the Archive produced during COVID-19 will be able to read from other viewpoints. And just as there is a multitude of forms within the COVID-19 Archive it will also be necessary to compare the COVID-19 Archive to those written in previous pandemics. The COVID-19 Archive must be read not only in isolation, but in its relation to other literatures: of previous pandemics, of crisis more generally, and as a manifestation of many to explain exactly what these events feel like to them.

Notes

1 Elizabeth Outka has recently made this point with particular force in her Viral Modernism. Jane Elizabeth Fisher approaches these questions from the perspective of women’s writing in particular in her Envisioning Disease, Gender, and War: Women’s Narratives of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. Much of the Australian scholarship is also focused on the 1918-20 Spanish Flu: see Bev Blackwell, Western Isolation: The Perth Experience of the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic and Matthew Wengert, City in Masks. I have recently sought to engage a broader group pandemics and their archives from a specifically literary studies perspective: see James Gourley, ‘Australia’s Plague Archive.’ Literary fiction itself has engaged with the pandemic experience, albeit from a significant temporal remove. Debra Adelaide’s Serpent Dust (2011) considers the impact of smallpox on Indigenous communities in the 18th century; Rowena Ivers’ Spotted Skin (1998) reads leprosy’s impact on Northern Australian communities in the 19th century; and Chris Womersley’s Bereft (2011) focuses on the Spanish’s Flu in western New South Wales in the 20th century.

2 [For eds – do you want this footnote?] That the COVID-19 pandemic is ‘unprecedented’ has been a default assumption of many. While not scientific, I offer here the following articles as indicative of this scholarly trend: Nkengasong, J. N. (2021). COVID-19: Unprecedented but Expected. Nature Medicine 27, 364; Yan, Z. (2020). Unprecedented Pandemic, Unprecedented Shift, Unprecedented Opportunity. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2(2), 110-12.

3 For instance, this discourse is very much like that which surrounds another recent event of world-historical significance: the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States. While popular and political opinion conceived of that event as coming ‘out of the blue’, scholars like Jacques Derrida and Annie McClanahan have shown how those attacks were continuous with United States’ neo-colonialism; it is, therefore, not reasonable to say the attacks were unprecedented. See Borradori, 2003; McClanahan, 2009.

4 NB that throughout 2020, the emotions communicated in the SLNSW’s Social Media Archive are always dominated by ‘joy’. In this case, sadness is the second-most prevalent ‘emotion’, which is not a regular occurrence in the 2020 data.

5 In April 2020, ‘Health’ will be superseded by a new category: ‘COVID-19’.

6 A useful timeline of early federal and state governmental actions is Wahlquist, 2020.

7 This is not to distinguish health and politics in their application to the COVID-19 situation, but rather to work within the framework provided by the SLNSW Social Media Archive.

8 On citizen writing see, for instance, Miriam J. Johnson, ‘The Rise of the Citizen Author: Writing Within Social Media,’ Publishing Research Quarterly 33 (2017): 131-46.

REFERENCES

ABC Radio Sydney (2021). This Moment in Time. https://www.abc.net.au/radio/sydney/a-moment-in-time/12216026.

Altschuler, S., & Wald, P. (2020). COVID-19: Pandemic Reading. American Literature 92(4), 681-8.

Bashford, A. (Ed). (2016). Quarantine: Local and Global Histories. London: Palgrave.

Bashford, A., & Hooker, C. (Eds). (2002). Contagion: Epidemics, History and Culture from Smallpox to Anthrax. Annandale: Pluto.

Blackwell, B. (2007). Western Isolation: The Perth Experience of the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic. Curtin: Australian Homeland Security Research Centre.

Borradori, G. (2003). Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Department of Health: Australian Government (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) current situation and case numbers. https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers.

Fisher, J. E. (2012). Envisioning Disease, Gender, and War: Women’s Narratives of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Gourley, J. (2020). Australia’s Plague Archive. Sydney Review of Books. https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/essay/australias-plague-archive.

Hobbins, P. (2020). Collecting the Crisis or the Collecting Crisis? A Survey of Covid-19 Archives. History Australia 17(3), 565-7.

Jane, E. A. & Fleming, C. (2014). Modern Conspiracy: The Importance of Being Paranoid. New York: Bloomsbury.

Johnson, M. J. (2017). The Rise of the Citizen Author: Writing Within Social Media. Publishing Research Quarterly 33, 131-46.

Malm, A. (2020). Corona, Climate, Chronic Emergency: War Communism in the Twenty-First Century. London: Verso.

McClanahan, A. (2009). Future’s Shock: Plausibility, Preemption, and the Fiction of 9/11. symplokē 17(1-2), 41-62.

O’Sullivan, D., Rahamathulla, M., & Pawar, M. (2020). The impact and implications of COVID-19: An Australian perspective. The International Journal of Community and Social Development 2(2), 134-51.

Outka, E. (2020). Viral Modernism. New York: Columbia UP.

State Library of New South Wales (2021a). Social Media Archive. https://socialmediaarchive.sl.nsw.gov.au/prototype/live.html.

State Library of New South Wales (2021b). The Diary Files. https://dxlab.sl.nsw.gov.au/diary-files/.

Wahlquist, C. (2020, May 2). Australia’s coronavirus lockdown – The first 50 days. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/02/australias-coronavirus-lockdown-the-first-50-days.

Wengert, M. (2018). City in Masks.Queensland: AndAlso Books.

World Health Organisation (2021). Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 Response. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline#!/.

About the author

James Gourley is a senior lecturer in literary studies in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University. He is a member of WSU’s Writing and Society Research Centre. His research addresses 20th and 21st century literature. His recent work has been published in ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, Sydney Review of Books, English Studies, College Literature and Thomas Pynchon in Context (Cambridge UP).

Email: j.gourley@westernsydney.edu.au