Scripting with the sports body

Sebastian Byrne

Western Sydney University

Abstract

The article explores the ways in which the body of the actor in the sports film can be more fully accentuated through a rethinking of the relationship between their sports performance and the other cinematic elements. This focus on the actor’s body will be achieved at the pre-production stage, through a short rehearsal video which represents an alternative form of scripting, known as ‘scripting with the body’ (Maras, 2009). This serves as an accompaniment to my unproduced screenplay, entitled Game, Set and Murder, in the genre of the sports film. The video carefully choreographs the movements of the actor as tennis player, training them to move in accordance with the camera. As a result of this previsualisation method, the actor’s bodily technique is foregrounded, culminating in the cinematic construction of the heightened sports performance and the delineation of the corporeal, tactile and sensory nature of the character. On another level, scripting with the body provides the screenwriter with a more dynamic role in the filmmaking process, facilitating a more corporeal collaboration between screenwriter, actor, cinematographer, and director that could ultimately translate into an embodied, multisensory viewing experience. To this end, such an alternative scripting methodology could also have significance and practical applicability for the wider screenwriting and filmmaking practices in their attempts to make the character readily translatable from the written page onto the screen, thus suggesting new directions for exploring the relationship between words and images.

Introduction

Through its dramatisation of action and events, the sports film can elicit visceral and emotional appeal for spectators. However, a criticism often attributed to the sports film is the actor’s lack of credibility in their bodily presentation of sports performance, wherein proper sporting technique is subordinated to an emphasis upon principles of psychological character and dramatic narrative (Sarris, 1980; Byrne, 2017; Godard, 2002, p. 74). Consequently, the use of cinematic techniques often works to enhance dramatic effect and thus serves to disguise the actor’s sports performance (Pomerance, 2006, p. 317), resulting in a lack of verisimilitude in their filmic portrayal (Sarris, 1980, p. 52). In this article, I look to address this limitation by exploring the ways in which the body of the actor in the sports film can be more fully accentuated through a rethinking of the relationship between their sports performance and the other cinematic elements. I believe that a more seamless and dynamic integration of the actor’s body within film production could lead to a closer delineation of their bodily technique, execution of sporting movement and engagement with the other actors, resulting in a ‘movement-narrative’ that achieves increased verisimilitude, and a more multidimensional, cinematic realisation of the character and corporeality in the sports spectacle (Anderson, 2006, sec. 2). By ‘movement-narrative’ I am referring to how narrative information can be presented through choreographed sports performance (Anderson, 2006). Such a focus in this practice-based research will be achieved at the previsualisation stage through a close analysis of the tennis sequences in my unproduced screenplay, entitled Game, Set and Murder, which is in the sports genre, and the accompanying short rehearsal video that presents an alternative mode of scripting, through what screenwriting theorist Steven Maras (2009) has called ‘scripting with the body’ (p. 125).

Rethinking the role of the screenwriter (and scriptwriting) in the filmmaking process through ‘scripting with the body’

Maras (2009, p. 125) describes ‘scripting with the body’ as a way of establishing a relationship between the actor, the screenwriter, the director and the camera, that can ‘best be described in terms of choreography’. The aim of this choreography, for Maras, is to direct the concept of scripting towards the ‘lived body’ to understand scripting beyond the manuscript or blueprint of the screenplay (p. 125).

An implication of working beyond the text-based screenplay to a focus on the actor’s body is that it challenges the separation of screenplay and concept on the one hand, and film and execution on the other. Maras (2009, p. 21) emphasises that the dominant logic of the Hollywood studio system is ‘organised around the separation of the work of conception and execution’ in which acting and film production are seen as functions on the ‘execution’ side of the separation, as opposed to the conception side. He adds that such a separation is institutionalised by dividing production into stages of preproduction, shooting and postproduction. Consequently, it becomes difficult to see scripting as a stage of execution (p. 22), as alternative modes of scripting, such as scripting with colour, sound, the camera and the body are excluded (p. 3).

Maras (2009, p. 1) elaborates upon this separation when he distinguishes between ‘screenwriting’ and ‘screen writing’. He defines screenwriting as ‘the practice of writing a screenplay, a manuscript understood through notions such as story spine, turning points, character arc and three act structure’ (p. 1). For instance, the focus on character psychology in screenwriting manuals could be located under the umbrella of screenwriting. Conversely, screen writing refers to:

… writing not for the screen, but with or on the screen. You can refer to a kind of “filmic” or “cinematic” or audiovisual writing – and it is worth remembering here that both cinematography and photography are etymologically speaking forms of writing (p. 2). 1

According to Maras, screen writing is synonymous with alternative modes of scripting, such as the ones mentioned above. While some studies in performance theory have concentrated on the relationship between language and movement (MacBean, 2001), the ‘cinematic’ writing made possible through Maras’s concept of screen writing has strong connections with the digital age and media convergence. As Kathryn Millard (2014) asserts, ‘the boundaries between the once discrete stages of writing, pre-production, production and post-production are ever more blurred’ (p. 7). Millard (2010) explains how many screenwriters and filmmakers have favoured audio and visual expressivity over plot and narrative drive, resulting in a variety of alternative scripting methodologies, including still photographs, visual art, sense memories, location pictures, video footage or popular songs (p. 13). Referring to Millard’s (2014) work on ‘screenwriting in a digital era’, Kath Dooley (2017) explores how digital filmmaking tools can inform script development. Establishing a method of scripting with the body, which she refers to as ‘digital underwriting’, Dooley (2017) directed actors in a series of short solo improvisations and ‘test scenes’ that interrogated ‘bodily movements and reactions in a number of proposed situations’ (p. 299). The footage from the workshops – which was documented through video cameras or mobile phones – then enabled Dooley (2017) to develop a first draft of her feature-length screenplay, Fireflies, with the intention of capturing the important role embodied experience plays in the narrative, including the ‘tactile and atmospheric elements in their [the actors’] surroundings’ (p. 302). Dooley’s method, in which audio-visual writing helped to inform the drafting of her screenplay, supports Maras’s (2009) argument that the aim of these other forms of scripting is not to enforce ‘a ban on three act structure in favour of “non-narrative” film styles’ – rather, it is ‘about connecting mainstream scriptwriting to a broader field of possibilities’ (p. 3).

The new possibilities and syntheses that emerge through alternative modes of scripting could provide a potential avenue for screenwriting research in the academy that is focused upon creative practice research, ‘whose aim is not to theorise practice per se, but rather to interrogate and intellectualise it in order to generate knowledge about new ways that we can practice’ (Batty 2016, p. 60). Acknowledging and examining different forms of screen writing could enable:

… practice-led or arts-based research as well as analytical insights of screenwriters into their practice [to] offer additional pathways for future writers and researchers’ (Sternberg 2014, p. 204).

This includes bringing to light pathways and practices that may have previously been marginalised due to a focus on commercial consumption in the industry (Batty, 2016). As a result of legitimising new screen writing methods of practice:

… interesting and productive bridges can be built between screenwriting research, screenwriting practice and mainstream practice-based discourse such as the screenwriting manual’ (Batty, 2016, p. 61).

A fundamental incentive that ‘drives’ my attempt to expand upon mainstream scriptwriting through alternative modes of scripting, namely scripting with the body, is to demonstrate how the accentuation of the actor’s physical skill set, and competitive bodily exchanges with the other players, could serve to open up dramatic storytelling principles. The character in the sports spectacle is often cinematically constructed through action that foregrounds their body in more demanding ways than in traditional narrative scenes. Consider, for example, the intricate camera movements and placements that were carefully mapped out in pre-production to capture professional rock climber, Alex Honnold, as he practiced climbing El Capitan’s ‘pitches’ in the sports documentary Free Solo (2018). Evidently, as the example from Free Solo would attest, a certain degree of sporting expertise or agility on the part of the screenwriter would be desirable in order for this scripting methodology to be most effective. With this consideration in mind, an advantage of utilising scripting with the body is that it can provide an intermediary position between the text-based screenplay and film production, by concretising sports performance through the choreographing of the actor’s bodily movements in relation to the camera, resulting in the capture and construction of a movement-narrative and a heightened sports performance at the stage of previsualisation. This performance and movement-narrative can then be further enhanced in production and postproduction, with the added use of lighting, digital composite and visual effects.

Through my attempt to create such a performance, I look to establish first a form of scripting that is able to understand writing on levels that both complement and go beyond conventional notions of plot and character, opening up the possibility to write with bodies and camera movement. In so doing, through the video I strive to provide a more pluralistic approach to screenwriting, while also adding more substance to the screenplay’s narrative and character development, by bringing more marginalised elements, such as cinematic form and the body, into the foreground.

Such a multilayered screenwriting methodology serves to create a bridge between the storytelling practices of the screenplay and the more immediate formal and bodily considerations involved in constructing sports performance and creating a film. As such, I am challenging the conventional division of labour between the screenwriter and the director. This division often establishes a hierarchy wherein the screenwriter is responsible for writing the script, which is then translated by the director into a workable shooting script to:

… serve as a guide for the director of photography, the assistant director, and the production manager, as well as the film editor in postproduction’ (Proferes, 2008, p. 116).

Thus, while the screenwriter is responsible for the film’s concept, they generally do not have creative authorial control over the screenplay and the scriptwriting process. Rather, it is the producer and the director who have the final say in creative decision-making, meaning that they can influence script development. For instance, Jill Nelmes (2010) argues that ‘the screenwriter often has to concede many changes in the screenplay because of the ease in which a writer can be so easily “hired and fired” by the producer(s)’ (p. 260). The screenwriter’s limited creative control over the final draft is particularly evident when they write a speculative or ‘spec’ script, which is a non-commissioned, unsolicited screenplay, in the hope that their screenplay might be optioned and purchased by a producer, production company or studio. Here, the ‘spec’ script screenwriter is often ‘obliged to leave plenty of room for an as yet unknown director to occupy’ (Davies, 2010, p. 154). Consequently, the role of the screenwriter and the screenplay can be seen as secondary within the filmmaking process, as priority is given to the execution of the audio-visual demands of production and editing.

Conversely, a key advantage of drawing upon scripting with the body to create a heightened sports performance is that the screenwriter and the other creative personnel can develop a more ‘organic’ relationship with the film as a whole. By developing a keen interest in the film’s aesthetics, and the bodies of the performers, the screenwriter can become a dynamic player in the collaborative process. Rather than solely being a writer who then hands over the screenplay to the actors and the technical crew, the screenwriter could instead be responsible for building the project from the ground up. By this I mean that the screenwriter could begin with the concept, followed by developing the interiorities of the characters, and the plot, before orally narrating the tennis sequences to the actors, and then incorporating the specifics of the body and the aesthetics of the camera to help transform the story from the page to the screen. Such a collaborative approach could in turn reconceptualise the role of the screenwriter by ‘challenging screenwriting research that focuses on the practitioner working in isolation from a field of social experts and a cultural domain of knowledge, one that divorces the screenwriting practitioner from a creative environment’ (Kerrigan & Batty, 2016, p. 139). Indeed, the benefit of the pluralistic approach to screenwriting that I present in this article is that it may promote a more seamless collaborative continuity between cast and crew throughout each of the stages of filmmaking, thus reinforcing a ‘screenwriting turn’ that challenges a ‘director-centric appraisal of screen works’ (Batty, 2016, p. 59). As such, the careful delineation of the bodily and internal dimensions of sports character within the screenplay and the rehearsal video could support, and be supported by, the technical expertise of visual effects supervisors, cinematographers, and editors, all working together from preproduction, thus providing a balanced acrobatics and aesthetics of filmmaking. In the following section I explicate the motivation behind adopting this method of previsualisation, describing the importance of oral narration, which represents the first stage of the video.2

Establishing an embodied connection between screenwriter and actor: Oral narration

During my doctoral candidature, I attended a short screenwriting course conducted by script editor and poet, Billy Marshall Stoneking (personal communications). One of the course exercises involved telling a short story to the class about one of our favourite objects. In my story, I talked about a pen that I had won earlier that summer in a speed serving competition in tennis. The story was about the ways in which I had practised my serve as a youth. What was interesting was that, as I told the story, I proceeded to do demonstrations of the serving techniques of past tennis professionals, such as Boris Becker, Goran Ivanisevic, Pete Sampras and Andy Roddick. In other words, the imitation of the service delivery of each of these tennis professionals and the execution of various bodily techniques played an instrumental role in the telling of my story to the class. Reflecting upon my story after having completed the course, what became apparent to me was the importance of the body in stories that are about sport. Incorporating bodily movement and technique with narration helped me to inject greater corporeal presence, immediacy and energy in my description of the narrative sequence of events, therefore enabling the other students to develop comprehension in my story through watching me perform.

In contrast to the freedom I experienced in telling the class a short story, it proved to be difficult translating this sense of bodily intensity and precision of choreography into the description of the tennis sequences within the screenplay, Game, Set and Murder. Although I was able to provide a brief description of the character’s bodily technique and movement, I felt that there was not enough room in the screenplay to capture the corporeal and visceral nature of sports performance, and that there was a limitation in using language to describe movement. Other screenwriting theorists, screenwriters and filmmakers address this problem of the somewhat restricted nature of the screenplay. Steven Price (2011, p. 203) argues that the physical details of the character, such as facial features, build and hairstyle, could help establish the realism in the story. However, according to Price (2011):

… the screenwriter is unable to present such detailed physical description, partly because of the need to defer in such matters to directors, designers and actors, and partly due to the sometimes-disputed convention that a page of script is equivalent to a minute of screen time. The writer simply does not have the words at his or her disposal to engage in leisurely description of people or places. In short, the screenplay is a structuring document that demands concentration on the shape of the story and the succession of events rather than on redundant physical detail (p. 204).

The restricted shape of the screenplay has led filmmaker Ingmar Bergman to envisage alternative modes of scripting. Bergman (1972) has said that ‘I have often wished for a kind of notation which would enable me to put on paper all the shades and tones of my vision, to recall distinctly the inner structure of a film’ (p. 8).

In a similar vein, filmmaker Wong Kar-wai notes that:

… you can’t write all your images on paper, and there are so many things – the sounds, the music, the ambience, and also the actors – when you’re writing all these details in the script, the script has no tempo, it’s not readable. It’s very boring. So, I just thought, it’s not a good idea [to write out a complete script beforehand], and I just wrote down the scenes, some essential details, and the dialogue (as cited in Brunette, 2005, p. 126).

My natural inclination to want to go beyond the limited scope of the screenplay by performing the movement of the players, as I had done in Stoneking’s course, led me to explore alternative modes of scripting, through the creation of a previsualisation rehearsal video in which I employed oral narration as a way of interacting with the actor in rehearsal. This method enabled me to complement and extend the screenplay with a more flexible, embodied and in-depth approach.

In adopting this method, I imitated the movements of the characters within the tennis sequences of the screenplay, demonstrating my own skill set and ability to imitate champion players, while making comments relating to the dynamics at play in the competitive interaction between the characters. The actor proceeded to imitate my movements, at the same time injecting their own physicality into the role, effectively resulting in the establishment of a chain of embodiment between me as the screenwriter, and the actor.

The ensuing embodied dialogue I established with the actor suggests how oral narration or live storytelling can perhaps engender a more intimate and visceral connection between storyteller and audience than in the relationship between screenplay and reader. Adam Ganz (2010, p. 225) argues that screenplays and films could learn from the oral narrative tradition of ballads, whose song and music are ‘rooted in action’ and therefore show ‘concision, energy and clarity in unfolding a narrative in real time’ and ‘are told rhythmically […] in front of an audience’ (p. 227). Rather than initiating a bodily dialogue between storyteller and audience, however, Ganz argues that the temporal and rhythmic qualities of the ballad help the viewer to visualise and piece together the story through vision and memory. Although it is an oral medium, Ganz (2010, p. 235) likens the ballad to a screenplay, illustrating how the ability to evoke the viewer’s memory of visual detail is achieved through the ways in which it utilises montage, such as through the juxtaposition of the narrative sequence of events, intercutting of multiple story strands and flashbacks. In his words:

[T]he meaning of the story comes not just from the events of the story but also from the juxtaposition between particular events and points of view, and the imagined connections and consequences, which the events and their juxtapositions evoke in the audience (p. 235).

Ganz (2010, p. 235) concludes that this focus on montage induces ‘speculation by an active audience’ in the production of meaning. In contrast to Ganz, the relationship I envisage between the storyteller and the audience (the actor in the rehearsal situation) suggests a more direct and embodied interaction, where comprehension is developed through the actor’s bodily imitation of the storyteller, rather than on a cognitive level built on visualisation. Laura Marks (2000) draws from Erich Auerbach to touch upon the potential for the storyteller to influence the actor on a material and sensory register when she discusses how ‘each time a story is retold it is sensuously remade in the body of the listener’ (p. 138).

The sensory connection between storyteller and listener has been understood through the voice of the storyteller. Rosamund Davies (2010) highlights how the director of the film Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), Alain Resnais:

… requested audio recordings of [the screenwriter, Marguerite] Duras reading the dialogue, so that he could reproduce, in the visual sequences and with the actors, the same rhythms produced by Duras’s voice (p. 169).

While my voice also played a role in narrating to the actor my movements and techniques, it was more through the performance of my body that I was able to influence them to reproduce the rhythms inherent in my demonstration. Hence, I would argue that the use of my voice and body in the rehearsal video, and the interaction that I established with the actor, are reminiscent of how I communicate as a tennis coach to my pupils. In tennis coaching, rather than simply telling the students how to move and utilise their bodies, I often combine instruction with a demonstration of the stroke. Furthermore, I encourage the students to execute combinations of strokes or patterns of play, known as ‘drills’. For example, a particular drill might emphasise movement from the baseline, in which the student commences in the centre of the court and then runs out wide to hit a forehand, before returning to the centre and then moving in the other direction to hit a backhand, before repeating the pattern several times. However, before the student performs the drill, I would often first demonstrate each of the stages, allowing the student to watch me execute the footwork and techniques. To this end, tennis coaching could be seen as a form of live storytelling or oral narrative, involving a bodily interplay between coach and pupil, and I borrowed from this coaching methodology to instruct the actor on court positioning, movement and technique.

Rehearsing a movement-narrative and a heightened sports performance through scripting with the body

Following the screenwriter’s oral narration, scripting with the body will focus on the rehearsal of the specific orchestration of movements undertaken by the characters within the tennis scenes contained in my screenplay, with the tennis ball to be added in postproduction. The purpose is to allow the screenplay’s main protagonist, world champion tennis player Jamie Janiero, and each of his opponents to play out the rallies that will demonstrate tactical play and court positioning. The opponent’s aim is to establish a style of play and then Jamie needs to find a way to overcome him. The filming at this initial stage can be executed in wide shot. The advantage of training the actors in this manner is that they can repeat the sequence of movement contained in each rally for numerous takes. Such a feat would be nearly impossible were the actors required to play tennis (Pomerance, 2006, p. 314).

This ability of the actors to coordinate their movements consistently, take after take, will greatly facilitate the execution of the next stage of scripting with the body, which looks to create a dynamic interrelationship between the bodies of the actors and the camera through the blocking of the action. The camera operators will be able to capture the action from a different perspective for each take. For instance, one take could follow one actor’s movement from behind at a low angle, while the next take could film them front-on in a tighter shot. The objective of creating a variety of perspectives, from a directorial point of view, is to enhance the performance of the actors through the accentuation of their various bodily techniques and the tactical patterns involved in their play, highlighting the contrasting styles of Jamie and his opponents. In so doing, it becomes possible to map out the court positioning and tactics of the players for maximum dramatic effect, as they look to defeat one another through the execution of their strokes. Ultimately, the accumulation of footage will allow the final movement-narrative to be constructed in the editing.

Filming in sequence shots could be of benefit to the camera operator, enabling them to get a feel for how to integrate the camera within film production. This method would be particularly beneficial when the camera operator moves in sync with the actor’s movements, establishing a sense of immediacy and intimacy in the relationship between the camera and the actor’s body, resulting in the projection of a visceral and corporeal intensity within the movement-narrative.

The training of the actor, and the close collaboration between the screenwriter, actor, camera operator and director in the previsualisation tennis rehearsal video, serves to rethink the actor’s preparation in films that rely upon the spectacle of the body, such as the sports, martial arts and action genres, in which bodily performance is often subordinated to a focus on digital technology. Siu Leung Li (2005) argues that in the film The Tuxedo (2002) almost no physical training by the actors is needed, and so the film ‘comes close to a total destruction of the mythic kung fu body and an affirmation of technology’ (pp. 60-61). She adds that while there would have been some training of kung fu needed in the film The Matrix (1999), ‘this [training] happens almost instantaneously through the computer implant and virtual reality’ (Siu, 2005, p. 56).

The subordination of the actor’s physical training to a focus on visual effects suggests how the traditional martial arts body is reappropriated into a digital body that performs a hybrid of fighting styles. Vivian. P. Y. Lee (2009, p. 121) comments on how there has been a transition from ‘an emphasis on the representation of ‘real kung fu’ to the so-called ‘wire fu’ and special effects-enhanced action and choreography’. She argues that the shift towards digitalisation means that various ‘authentic’ fighting styles, such as kung fu and wuxia (sword fighting), become subsumed into a homogeneous, ‘hyperreal’ representation of the body that has appeal to a global audience (Lee, 2009, p. 122).

Siu and Lee’s comments allude to a direct correlation between the lack of attention given to the training of the actor’s body in preproduction and the way in which digital technology, visual effects and special effects have superseded the actor’s bodily performance. However, while I acknowledge that digital technology influences the construction of the character in sports and martial arts spectacle sequences, I would argue that the actor’s body need not be divorced from the on-screen aesthetics, but rather, that their body could work in a productive relationship with the digital interface. But to achieve this dynamic interplay and integration between the actor and the cinematic techniques and digitalisation, the actor would need to perform a lot of specific and intense training. Hence, the changes in CGI and visual effects pave the way for modulations in preparation for the actor to foreground more actively bodily performance than in classical realist representations, while simultaneously preserving the specificity and verisimilitude inherent in their bodily technique.

Alternative modes of scripting: Extending beyond the text-based screenplay

In the following section I attempt to locate this method of scripting with the body in my project within the wider filmmaking context, commencing with a discussion of alternative modes of scripting, which are often in response to the limitations of the screenplay, and are usually designed to challenge and subvert mainstream cinema. J. J. Murphy (2010, p. 193) highlights how, because they often work outside of the mainstream and industrial conventions, independent filmmakers are not specifically tied to mainstream storytelling structures and conventions. As a result, they often utilise improvisation, where scripting is about ‘doing’ rather than ‘pre-planning’ (Murphy, 2010, p. 178). This focus on improvisation privileges an ‘open-ended’ approach (p. 183), meaning that the story can be found in the process of filming (p. 184).

Conversely, my use of oral narration and scripting with the body does not imply a breakaway from industry conventions and the written page but is a way of expanding more productively the screenplay in mainstream narrative cinema, thus emphasising a focus on preplanning, and a way of extending the blueprint of a well-developed screenplay, as opposed to open-ended improvisation. Therefore, perhaps my utilisation of scripting with the body comes closer to some of the alternative scripting methods that feature in animation. Paul Wells (2011, p. 89) argues that the nature and definition of ‘script’ is problematic when considering animation in the films of Disney Pixar and suggests that scripting needs to be viewed in a broader light, in order to accommodate animation practices that build the narrative through the incorporation of motion, visual and sonic elements that are not found in the screenplay. Wells (2011, p. 95) comments upon how animation relies heavily on expert and detailed planning in relation to its execution in the preproduction phase, more so than live action which can be corrected in postproduction.3 To this end, storyboarding in Disney Pixar films have ‘enabled the narrative to develop with a visual immediacy that facilitated collaborative interventions, and a collective understanding of the evolving narrative’ (p. 92).

In a similar vein, the corporeal presence, bodily movement and technical prowess of the actor as sportsperson could strengthen the sports film, but these physical attributes tend to be elided in the screenplay. Therefore, I would argue that the sports spectacle would benefit from the ways in which scripting with the body could provide a more dynamic and intimate way of capturing and constructing sports character and narrative, effectively showing the story through the interplay of bodies and the camera in motion. Such a method provides an audio-visual blueprint that exceeds the screenplay manuscript, ultimately encouraging an increased collaborative and corporeal correlation between the actor, the screenwriter, the director and the other creative personnel during film production and editing.

Principal players

Jamie Janiero is a classical all-court player, who is equally adept at playing from the baseline as he is from the net.

Anthony Janiero Junior is a big, natural athlete who resembles tennis professionals Andy Roddick and Juan Martin del Potro, due to his enormous power and physical prowess.

Greg Bertram is a hyper-masculine, powerful left-hander who plays in a similar way to the former world number one, Rafael Nadal. He generates enormous topspin.

Karel Mueller is a dour, grinding competitor, who moves like the Road Runner. He is like a human ball machine: fast, extremely fit and very consistent. Mueller is a veritable ‘golden retriever’, à la the Australian champion, Lleyton Hewitt.

John Paul Bergman is an unorthodox player who likes to use a lot of different spins.

The creation of a diverse group of opponents for Jamie in the screenplay serves to establish physical and internal contrasts, as well as to help make concrete the various tactical patterns of play.

Stage one: The screenwriter’s demonstration of the characters’ movements

I intend to perform the tennis movements of each of the characters individually myself, while the actor watches. During each demonstration I imitate the character’s court positioning and stroke production, as if I am presenting a tennis drill to my student. Furthermore, I make comments that are more specific to the narrative, such as ‘Jamie is on the back foot here because of Bertram’s heavy topspin’. While this form of oral narration is informed by the plot description within the screenplay, it is not a memorised word-for-word account. Rather, I rely upon conveying the story primarily through the use of my body, and only some instruction is given. I feel that this approach allows greater flexibility for self-expression through bodily movement, rather than being hampered by screenplay description which tends to be more literal (I don’t need to say I hit a backhand when the actor can see me doing so) and unable to capture the seamless choreography, and underlying corporeal and tactile sensation that I encounter when travelling along the surface of the tennis court. Ultimately, it is this multisensory awareness and experience of inhabiting the character’s physicality that I hope to impress upon the actor.

While I believe that this form of oral narration can encourage a bodily response in the actor, leading them to imitate more effectively my movements, the aim is then to translate this bodily interaction between the screenwriter and actor into the next stage, in which the actors play out the rallies with one another. It’s important to perform the rallies with the opponent, as opposed to working in isolation, because each of Jamie’s movements is informed by their tactical play. Jamie and his opponent feed off one another, pushing each other in the rally. Together, they work towards a movement-narrative that helps build action in the plot, establishing a chain of cause-and-effect through a dialogue between their bodies (to be further accentuated through cinematic techniques).

A useful metaphor to describe the dynamics of the bodily dialogue that emerges in the rallies can be found in Sanford Meisner’s (1987) book on acting when he talks about the ‘pinch’ and the ‘ouch’. According to Meisner (1987, p. 35), if the actor’s line in the script is ‘ouch’, they should not worry about how they say the line. Rather, they should respond truthfully to the pinch that they receive from the other actor. From there, if the actor needs to change their delivery of the ‘ouch’, they should ask their acting partner to pinch them harder. As a result, the actor will be responding to the pinch they receive, similar to a cause-and-effect interaction, rather than simply manipulating their reading of the line.

In a similar vein, it is the quality of the opponent’s stroke that determines Jamie’s reaction. For instance, a quality aggressive shot in the corner would force Jamie to stretch for the ball. By the same token, it is worth adding that the stroke making of both players lends itself to variations on Meisner’s analogy. There are instances where not only does Jamie react to his opponent’s stroke (the ‘ouch’), but he responds accordingly with his own stroke (the ‘pinch’). For example, Jamie’s third round opponent, Karel Mueller, angles Jamie out of court (the ‘pinch’) but Jamie responds with an even better stroke that goes around the net post for a winner (an unreturnable ‘pinch’), effectively turning defence into attack.

Stage two: Integrating the actors’ bodies with the camera

Each of the matches will firstly be filmed in wide shot, with the camera placed on a tripod, to establish the geography of the court, making the court positioning of each player clear to the viewer. Capturing the entire depth and width of the court in wide shot can show where the ball is landing, thus providing clarity as to who is doing what to whom within the dynamics of competition. This wide shot will then be repeated from the opposite end of the court. In addition, if and when I proceed to make the film in the future, film production could benefit from a higher angle crane shot in order to provide a variation on this wide shot, and, depending on the budget, could be extended to show an overhead shot of the entire Melbourne Park tennis complex.4

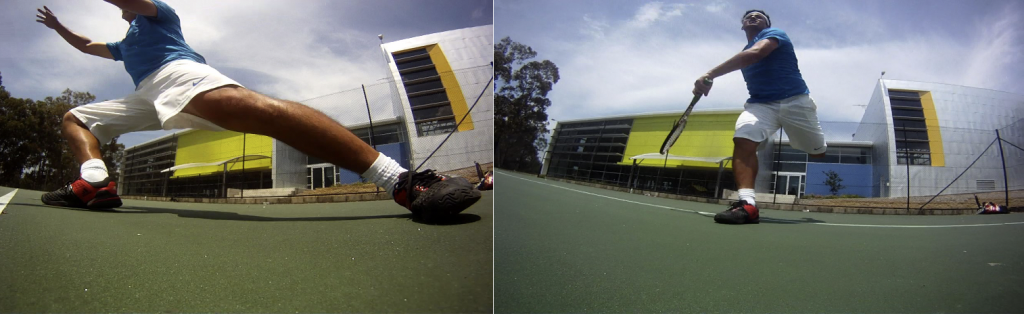

Once the geography has been established, however, I would like the camera to create a more intimate relationship with the bodies of the players, as if positioning the viewer within the very ‘heat of the battle’. To achieve this intimacy, I intend to have the camera placed as close to the action as possible, and at a low angle, which captures the actors closer to gravity. This technique thus creates a heightened sense of their movement, for instance by spotlighting their footwork, while at the same time exploring the texture of the court surface and the bounce of the ball (when it is added in postproduction) by positioning the camera directly on the ground or attaching it to the player’s ankle.5

By moving the camera in close, I look to break down the action by focusing on either player individually, as I want the camera to work in parallel with the movement of the player. For example, in one sequence shot, the camera can follow the player as he moves from side-to-side. This form of movement would be particularly effective when capturing the bodily technique of Bergman from front-on, to emphasise the repetitive and monotonous nature of his stroke production. On another take, the camera can move into the player just as he moves into the ball, thus creating the illusion that the two will collide when the player makes contact.6 This use of camera movement, in combination with the use of a zoom for variation, would be ideal for accentuating the brutal power exploding off Anthony’s racquet on the serve, the racquet head speed produced by Bertram’s forehand, or even the deft touch contained in Bergman’s slice backhand. By creating camera movement in sync with the player’s bodily technique, it becomes possible to create a more ‘organic’ relationship between the two, and an intimate and visceral experience for the viewer, in contrast to television’s tendency to telecast live tennis from a high, static camera angle. Indeed, this close correlation between camera movement and the actor’s physicality could heighten the tactile nature of viewing sports sequences by allowing the viewer to develop a ‘feel’ for the players’ variations in stroke production. For instance, the viewer could glide with the camera as it follows a delicate slice backhand, before experiencing an unexpected jolt through Anthony’s explosive impact with the ball. Hence, the movement of the camera could encourage the viewer to share the cinematic space with the actors, thus creating a mutual sensory and tactile perception and experience between the bodies on the screen and the viewer.7

Another way of immersing the viewer within the action is to use a subjective camera. Instead of filming Jamie from behind, Jamie could assume the perspective of the camera, perhaps by attaching a light HD camera to his body, such as the wearable Hero Go Pro camera which was specifically designed for capturing action in extreme sports, so that the viewer literally experiences the competition from Jamie’s movement and point of view. By positioning the viewer at closer proximity to Jamie, the speed of the opponent’s stroke play could register more fully for the viewer than when the camera is further back, therefore allowing them to participate in Jamie’s quest for victory. Thus, rather than providing a detached gaze, the camera would achieve a more material presence, almost morphing into the physicality of the actor, while reinforcing the blurring of boundaries between the screen and the viewer.8

This use of the wearable subjective camera (the Hero Go Pro) could examine the player’s stroke production and bodily range of motion in closer detail than might be possible with a more conventional digital camera. For example, attaching the Go Pro camera to a chest strap worn by the character, Bertram, could allow the actor to accentuate his chest, torso and hip flexor rotation on his forehand, while attaching it to his wrist strap could heighten his wrist snap, pronation, and the velocity of the contact point and follow-through on his serve. In so doing, his strokes could appear to be more lethal weapons.9

Such a mirroring of the camera with the actor’s body could also be achieved by panning the camera from the stroke of one player to the other. But rather than simply performing several swish pans at the same speed and camera height as in the film Wimbledon (2004), the camera could commence at the height of the player’s contact point and then tilt up or down as it pans, depending on the trajectory of the imaginary ball coming off the racquet. For instance, Bertram is renowned for imparting heavy topspin on his forehand, resulting in the ball looping over the net. In one take, the camera could commence low on Bertram as he whips a forehand near ground level. The camera could proceed to tilt up as it follows the rising arc of the imaginary ball. Conversely, the flight of Bergman’s slice backhand travels much lower across the net. Therefore, the camera could commence directly level with Bergman’s shoulder as he makes contact with the ball above the waist. It could proceed to slowly pan and tilt down with the floating ball, before returning to Bergman and performing a swish pan with one of his flat forehands, this time remaining at a constant waist level throughout.

The various uses of a following pan and tilting in the above examples emphasise how the underspin of a sliced stroke takes longer to travel to the other side of the court than a flat or topspin drive, while also demonstrating their different heights over the net. Hence, operating the camera in this manner draws attention to some of the ways in which it becomes possible to create a more intimate connection with the actors’ bodies by creating a parallel with the players’ different strokes in terms of variations in height and speed of motion. In so doing, the camera effectively becomes an additional player in the tennis match, as its dynamic ‘toing’ and ‘froing’ helps relay a mobile chain of kinetic energy, therefore illuminating the sports film’s potential to develop an increased technological corporeality.

The above-mentioned approach to rehearsal highlights how the screenplay can be extended into an embodied mode of address in which the screenwriter’s body serves as a storytelling tool, through their oral narration, to instruct the actors to present the story through their bodies within the movement-narrative, while the technical personnel interpret the actors’ movements, thus culminating in an embodied circuit of collaborative interplay during the preproduction process.

While it is common for actors to be instructed by professional sports players and coaches, such as former Wimbledon champion Pat Cash in Wimbledon (2004), the screenwriter can provide a more detailed and specific oral narrative because they know all the movements in the screenplay, hence they can combine the execution of sports techniques and instruction with narrative description, resulting in the articulation and presentation to the actor of a corporeal and tactile movement-narrative. In so doing, I would argue that the screenwriter can greatly influence the actor’s imitation skills, thereby facilitating the actor’s credibility in the role of sportsperson, not to mention the mimetic experience they can produce for the viewer.

On another level, I believe that this approach to rehearsal provides an effective basis at the previsualisation stage for a movement-narrative, where additional elements can subsequently be added during film production and editing. My vision for the film’s aesthetics would be that the tennis sequences look to draw on computer-generated imagery to design different tennis balls that can each represent different spins and speeds of tennis strokes. The aim of the CGI tennis balls would be to showcase the contrasting bodily make-ups of the players, established originally in rehearsal. This heightening would be achieved by foregrounding the physicalities and movements of the players and drawing close attention to differences in terms of their strokes (spins, speed, trajectories), temperaments and techniques, rather than neutralising the game, as it is presented on live television. By emphasising differences in stroke production between Jamie and his opponents, through the creation of various CGI balls, it would then be possible to establish further patterns of play, and to illustrate at greater magnitude the pronounced contrasts between the players – as opposed to the homogenisation in techniques, styles of play and physicalities in Players (1979), Wimbledon (2004) and Battle of the Sexes (2017).

For example, Jamie would be of average height, and all of his opponents are either bigger or smaller, counter punchers (as in players who are quick and play defensively), attacking players, unorthodox players or big servers. Jamie would have to tailor his all-court game in order to break down the relentless patterns of his foes. Camera movement, editing, sound (each shot has a different sound, from the booming noises ricocheting off Anthony’s racquet, to the softer sounds of Jamie’s crisp hitting) and CGI would all be used to enhance the representational characteristics of the players’ stroke production, and their physicalities, rather than to disguise their techniques. Consequently, this method would culminate in the creation and cinematic construction of a heightened sports performance and audio-visual movement-narrative.

Conclusion

By drawing upon the practice of scripting with the body I present a pluralist approach to screenwriting for the purpose of amalgamating the principal storytelling practices of the screenplay with the cinematic construction of sports character. In so doing, I look to rethink the role of the screenwriter within the broader filmmaking process. Rather than relegating the screenwriter solely to the role of writing the text-based screenplay, I believe that their engagement in the creation of a form of bodily scripting can provide them with a pathway into the more immediate cinematic facets of the film, namely through their oral narration and the blocking of action at the previsualisation stage. By expanding upon the screenwriter’s role, the potential exists to allow the screenwriter to establish a fruitful relationship with the other creative film crew personnel, namely the actor and the director, perhaps resulting in a more ‘organic’ development of the sports film in which the various stages of filmmaking can be taken into consideration during preproduction. Such an engagement could result in a more seamless integration of character in the text-based screenplay, with the building of the actor’s sports performance.

The intermediary position that scripting with the body in my project provides between the screenplay and film production can serve to project more effectively the actor’s body on the screen. In so doing, scripting with the body can foreground the actor’s bodily technique in ways that extend beyond their depiction in conventional sports films, moving instead towards a heightened sports performance and movement-narrative, brought to fruition through the capture and construction of a detailed bodily interplay between the actors, simultaneously working in tandem with the camera and the editing. This harmonious and interactive relationship between bodies, the mise en scène and cinematic form establishes a working interface that can then be digitally enhanced in postproduction (as in through the integration of CGI tennis balls), culminating in the presentation of a unified technological corporeality, which in turn could illuminate the tactile and sensory nature of embodied spectatorship.

Moreover, the ability to establish an embodied, collaborative relationship between cast and crew during preproduction is largely made possible through advances in digital technology, which are cost-effective, and therefore can allow smaller crews and longer takes, resulting in greater flexibility and intimacy during filming (Murphy, 2010). Filmmaker David Lynch (as cited in Murphy, 2010) captures this experience of working through digital means when he comments, ‘now you’re right in there, and you’re feeling it and seeing it and you can do things, subtle, little things, that come out of what you’re witnessing’ (p. 187). Although Lynch is referring here to a type of low-budget independent filmmaking where the story is discovered during film production, rather than initially through a written screenplay, his comment about being ‘right in there’ and ‘feeling it’ lends force to an intimate, immediate and visceral filmmaking experience that best describes the corporeal, tactile and multisensory collaboration that took place in the creation of sports performance in the rehearsal video.

Ultimately, the resultant sense of proximity that was achieved between the cast and crew in my project – made possible through digital technology – suggests an effective previsualisation filmmaking methodology. A stepping-stone can be established that informs actors, screenwriters and filmmakers in mainstream films in their search for a collective engagement and awareness in the portrayal, capture and construction of bodily performance in spectacle sequences through this methodology – a methodology that would be directly applicable, for instance, to the orchestration of elaborate long takes in the battle sequences of 1917 (2019). In so doing, it would become possible to move in the direction of Lesley Stern and George Kouvaros’s (1999) objective of conjuring the presence of cinematic performance through a delineation of physicality, gesture, movement and the senses (p. 11).

In addition to instigating a close collaboration between cast and crew, the cost-effective method of scripting with the body that I adopt in this research could have important implications for low-budget and experimental filmmakers. The dynamic and innovative ways in which the rehearsal video looks to capture the physicality and movement of the actor through the camera and the editing helps establish a spectacle that is more easily accessed through less expensive previsualisation and film production practices. Hence, rather than being limited to working exclusively with narrative scenes focusing on dialogue, filmed in a minimum number of settings (Newton & Gaspard, 2007), low-budget filmmakers could have the luxury of exercising this mode of bodily scripting to give the impression of an increased production value to their projects through the frequent use of the mobile camera and fast cutting (Rodriguez, 1992). At the same time, experimental filmmakers would have the opportunity to examine how the body moves through time and space, perhaps discovering more intricate ways of filming movement. Hence, an advantage of this practice-based research’s detailed analysis of how the actor’s body operates within the plot of the sports spectacle is that it could inform and educate filmmakers and theorists across various filmmaking contexts and genres. Thus, it could enable a fruitful dialogue to emerge between popular cinema and those films that exist on the periphery of mainstream filmmaking (Mills, 2009).

By the same token, the opportunity exists in the future for a closer examination of how to film action in sports sequences beyond the method I present in the rehearsal video. For instance, advances in camera technology could increase the corporeal intimacy in the camera-actor relation. While the Hero Go Pro camera is light and comes in protective casing, the next stage could be an increasingly weightless camera with a casing that would allow it to be thrown around, or even fired from a gun or a slingshot, therefore coming even closer to replicate the speed, spin and trajectory of a tennis ball. This would allow increased fluidity, and a more realistic representation of the time it takes for the ball to travel from the player’s contact point to the opponent’s racquet. The ultimate goal would be to create a camera that is so minuscule and malleable that it could be positioned on the tennis ball, and the players could hit it back and forth as in a normal rally.10 Consequently, the camera might be able to absorb, like a sponge, all the nuances of the players’ various blows and kinetic energies, for instance by showing if the player centred the ball on the strings, or whether the stroke may have been mistimed. Furthermore, additional cameras could be attached to the player to delineate more closely their movement.

This potential to highlight the stroke production of the actor as sportsperson in closer detail, brought about through future technological advances in the cinematic apparatus, could result in the camera more accurately conveying the ways in which sports performance can be affected by the actor’s psychological and emotional states. For instance, the actor’s ability to perform their character’s nervousness and self-doubt on a critical point could lead to an impediment in their swing pattern which in turn could impact upon the smoothness and direction of motion of the wearable camera. As a result, the camera might be better able to evoke more fully in the viewer the feeling of dramatic tension that permeates the actor’s body, ultimately elevating the bodily affect that relays in a reciprocal exchange between actor and viewer onto new multisensory registers of mimetic engagement and experience.

Notes

1Maras’ notion of writing on the screen has parallels with theorist Alexander Astruc’s (1968, p. 161) metaphor of the ‘camera-stylo’, or ‘camera-pen’, in which the filmmaker ‘writes with his camera as a writer writes with his pen’ for the purpose of opening up cinema’s potential to find its own language in the expression of thought, and to move beyond the simplistic psychological and storytelling models of early post-war American and European cinema. Consequently, the screenwriter/director distinction is abolished, as direction becomes ‘a true act of writing’ (161). Astruc’s ‘camera-stylo’ metaphor has been extended in the films of the ‘French New Wave’ directors of the late 1950s, such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, through their use of lighter, more mobile cameras, natural lighting and location shooting (Monaco, 1976).

2 While I am focusing almost exclusively on the movements and sports techniques of the actors in the tennis sequences, I acknowledge that their roles also encompass other performative demands. Therefore, the actors will require other forms of rehearsal, such as read-throughs, in which they read aloud the screenplay to one another in order to become acquainted with the dialogue, the beats and their character’s throughline or super objective (Irving 2010: 36). In addition, the actors can incorporate improvisation during rehearsals to help them discover the emotional ‘truth’ of the scene (37).

3 Live action refers to content that is captured with a real-world camera (Allen & Connor, 2007, p. 3).

4 Alternatively, a jib-arm could be used to establish the height needed to create a shot looking down on the court.

5 Another way of achieving this low angle in film production would be to place the camera in a hole below the court surface, and have it tilting up. A similar method was employed by actor and director Orson Welles and cinematographer Greg Tolland during the filming of Citizen Kane (1941). They were able to film the interior of a room from a low angle by placing the camera in a sandpit that existed below the level of the floor (Welles, 1941).

6 It would even be possible to have a player’s first serve hit the camera in production, as if it had hit a television camera at the back of the court, or it could hit a hidden camera nested in the net!

7 Film production could also benefit from the use of tracks and a dolly to provide smoother movement of the camera that could contrast with the camera wobble in the handheld compositions, thus providing a variation on how to film the actor’s mobility.

8 A limitation of the Hero Go Pro camera, however, is its very narrow depth of field. Therefore, in order to maximise the effectiveness of this camera in film production, I believe that it would be beneficial to play on a slightly miniaturised tennis court, which would bring the opposing player into focus. Such a shrinking of the playing arena could also create a greater physical immediacy in the interchange between the players.

9 The chest and wrist straps are accompanying accessories to the Hero Go Pro camera

10 A similar method is employed in the film The Big Lebowski (1998) where a camera is firmly attached to a bowling ball as it rolls down the aisle towards the pins.

References

Allen, D. & Connor, B. (2007). Encyclopaedia of Visual Effects: The Ultimate Guide to Creating Effects in Shake, Motion, and Adobe After Effects. Peachpit Press.

Anderson, A. (2006). Kinaesthesia in martial arts films: Action in motion. Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 48. http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC42folder/anderson2/text.html.

Batty, C. (2016). Screenwriting studies, screenwriting practice and the screenwriting manual. New Writing, 13(1), 59-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790726.2015.1134579.

Bergman, I. (1972). What is ‘film making’? In H. M. Geduld (Ed.). Film Makers on Film Making: Statements on their Art by 30 Directors, (pp. 182-194). Penguin.

Brunette, P. (2005). Wong Kar-wai. University of Illinois Press.

Byrne, S. (2017). Actors who can’t play in the sports film: Exploring the cinematic construction of sports performance. Sport in Society 20(11), 1565-1579. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1284806.

Cohen, J. & Cohen. E. (Directors). (1998). The Big Lebowski. [Film]. Working Title Films.

Davies, R. (2010). Screenwriting strategies in Marguerite Duras’s script for ‘Hiroshima Mon Amour’ (1960). Journal of Screenwriting, 1(2), 149-173.

Donovan, K. (Director). (2002). The Tuxedo. [Film]. DreamWorks Pictures.

Dooley, K. (2017). Digital ‘underwriting’: A script development technique in the age of media convergence. Journal of Screenwriting, 8(3), 287-302.

Faris, V. & Dayton, J. (Directors). (2017). Battle of the Sexes. [Film]. TSG Entertainment.

Ganz, A. (2010). Time, space and movement: Screenplay as oral narrative. Journal of Screenwriting, 1(2), 225-236.

Godard, J. (2002). Jean-Luc Godard: The future(s) of film: Three interviews, 2000-01 (J. O. Toole, Trans.). Gachnang & Springer.

Harvey, A. (Director). (1979). Players. [Film]. Paramount Pictures.

Irving, D. K. (2010). Fundamentals of Film Directing. McFarland & Co.

Kerrigan, S. & Batty, C. (2016). Re-conceptualising screenwriting for the academy: The social, cultural and creative practice of developing a screenplay. New Writing, 13(1), 130-144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790726.2015.1134580.

Lee, V. P. Y. (2009). The Kung Fu Hero in the Digital Age in Hong Kong Cinema since 1997: The Post-nostalgic Imagination. Palgrave Macmillan.

Loncraine, R. (Director). (2004). Wimbledon. [Film]. Studio Canal.

MacBean, A. (2001). Scripting the body: The simultaneous study of writing and movement. Journal of Dance Education, 1(2), 48-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2001.10387177.

Maras, S. (2009). Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. Wallflower.

Marks, L. (2000). The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Duke University Press.

Meisner, S. (1987). Sanford Meisner on Acting. Vintage Books.

Millard, K. (2010). After the typewriter: The screenplay in a digital era. Journal of Screenwriting, 1(1), 11-25.

Millard, K. (2014). Screenwriting in a Digital Era. Palgrave Macmillan.

Mills, J. (2009). Loving and Hating Hollywood: Reframing Global and Local Cinemas. Allen & Unwin.

Monaco, J. (1976). The New Wave: Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, Rohmer, Rivette. Oxford University Press.

Murphy J. J. (2010). No room for the fun stuff: The question of the screenplay in American indie cinema. Journal of Screenwriting, 1(1), 175-196.

Nelmes, J. (2010). Collaboration and control in the development of Janet Green’s screenplay Victim. Journal of Screenwriting, 1(2), 255-271.

Newton, D. & Gaspard, J. (2007). Digital Filmmaking 101: An Essential Guide to Producing Low-budget Movies (2e.). Michael Wiese Productions.

Pomerance, M. (2006). The dramaturgy of action and involvement in sports film. Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 23(4), 311-329.

Price, S. (2011). Character in the screenplay text. In J. Nelmes (Ed.). Analysing the Screenplay, (pp. 201-216). Routledge.

Proferes, N. (2008). Film Directing Fundamentals: See your Film before Shooting. Focal Press.

Raimi, S. (Director). (2019). 1917. [Film]. DreamWorks Pictures.

Resnais, A. (Director). (1959). Hiroshima Mon Amour. [Film]. Argos Films.

Rodriguez, R. (Director). (1992). El Mariachi. [Film]. Colombia Pictures.

Sarris, A. (1980). Why sports movies don’t work. Film Comment, 16(6), 49-54.

Siu, L. L. (2005). The myth continues: Cinematic kung fu in modernity. In M. Morris, S. L. Li & S. C. Ching-kiu (Eds.). Hong Kong Connections: Transnational Imagination in Action Cinema, (pp. 49-61). Duke University Press.

Stern, L. & Kouvaros, G. (1999). Descriptive acts. in L. Stern & G. Kouvaros (Eds.). Falling for You: Essays on Cinema and Performance, (pp. 1-35). Power Institute.

Sternberg, C. (2014). Written to be read: A personal reflection on screenwriting research, then and now. Journal of Screenwriting, 5(2), 199-208.

Vasarhelyi, E. C. & Chin, J. (Directors). (2018). Free Solo. [Film]. National Geographic Documentary Films.

Wachowski, L. & Wachowski, L. (Directors). (1999). The Matrix. [Film]. Warner Bros.

Welles, O. (Director). (1941). Citizen Kane. [Film]. Mercury Productions.

Wells, P. (2011). Boards, beats, binaries and bricolage: Approaches to the animation script. In J. Nelmes (Ed.). Analysing the Screenplay, (pp. 89-105). Routledge.

About the author

Dr Sebastian Byrne has been teaching at Western Sydney University for twelve years, tutoring in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts, and Social Sciences specialising in Cinema Studies. He completed his Doctorate of Creative Arts (DCA) in 2012 which comprised an exegesis, and a feature-length screenplay, entitled Game, Set and Murder, written in the genre of the sports film. The exegesis explored ways in which the character is constructed in goal-driven narrative cinema, with a case study on the performance of the actor in the sports film. Since completing his doctorate, he has written two screenplays, collaborating with script editor and animator, Jack Feldstein, and is currently seeking funding, while also preparing a journal article based on performative dimensions in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There will be Blood.