Cut and Paste: Australia’s Original Culture Jammers, BUGA UP

Milissa Deitz

University of Western Sydney, Australia

Abstract

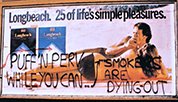

The late 1970s saw the rise of an unusual form of civil disobedience in Australia in support of public health. ‘Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions’ (BUGA UP) addressed what they perceived to be the adverse effects of tobacco and alcohol advertising by devising graffiti campaigns throughout Australia, predominantly in Sydney. Billboards were modified, usually through the erasure or addition of letters, to create negative messages about the products they were promoting. The group attracted a diverse range of activists – many of them drawn from professional life – and the ‘subvertisers’ remained highly active throughout the 1980s.

What has come to define a host of activities under the broader term of media activism, arguably began life in Australia as billboard alteration. In historicising early forms of such activism in the context of current media scholarship, I wish to challenge the assumption of some media activism literature in defining certain phenomena as part of a contemporary movement that emerged with digital media. There are precursors with older forms of activism deserving of attention. Little scholarly material concerning BUGA UP exists and the organisation while often mentioned in media activism literature, is rarely analysed.

The article argues that BUGA UP has a place in the pre-history of ‘culture jamming’ in Australia and should be recognised as a forerunner to such activism in which the basic intent has remain unchanged, even if the form and medium has evolved. Political and cultural attitudes to media consumption aside, BUGA UP was a pioneering movement that represented a watershed moment in media-based forms of activism in Australia, and should be recognised as such.

Introduction

The 1970s were coming to an end. Audiences were drawn to the creature comforts of the very first Muppet movie while Norm, a middle-aged man with a beer belly drawn to represent an average Aussie bloke, told us in government-funded advertisements promoting the prevention of chronic disease: “Life. Be in it today, live more of your life”. Children were not driven to and from school as a matter of course, and no one had air conditioning in their cars, let alone their houses. But while the Bee Gees were topping the charts and Paul Hogan was breaking hearts, a small group of professionals was gathering to break the law in the name of public health. The 1970s was also the decade when punk was peaking, uranium mining and protests against it had resumed, and Australia was in the immediate wake of arguably the country’s first act of terrorism, the Hilton bombing. Yet for people to mobilise and conduct themselves in an illegal and creative way in the service of good health, (and by extension, against corporate greed), was a striking phenomenon at the time.

In this historical context, ‘Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions’ (‘BUGA UP’) was a group of Australians who decided to counter what they believed to be the adverse effects of tobacco advertising on the wider public by devising graffiti campaigns. These campaigns occurred predominately in Sydney, but also throughout other Australian cities, in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s. In interviews with a number of the original members of BUGA UP, I found their aims to have much in common with contemporary ‘culture jamming’ – an organised activist strategy that challenges routine thinking via the appropriation of advertising or a brand-name although BUGA UP’s tactics were necessarily less refined in the absence of the sophisticated and domesticated technologies available to today’s activists. And while Christine Harold has argued that contemporary culture jamming addresses the patterns of power (2004, 211), BUGA UP focused more on the contents of the advertising itself.

1 BUGA UP is, arguably, the first Australian instance of what the internationally recognised, Canadian-based group Adbusters, now call ‘subvertising’. It seems to me important that the early practitioners of what we may call culture jamming are recognised for their contribution to its Antipodean form. So, while the focus of this article is not contemporary culture jammers, I would like to consider this predecessor of such activism in order to examine and historicise the cultural and political practices of this group of Australians. In their original incarnation, MOP UP, they were responsible for two notable achievements before forming BUGA UP, a body responsible for, in the words of one of the founding members, Professor Simon Chapman, “arguably the most common anti-smoking message presented to the average Australian” (p184).

Culture jamming

What has come to define a host of activities under the broader term of media activism, arguably began life in Australia as billboard alteration. Media activism 2 is directed at sites of authority – the mainstream media, corporate business and mainstream politics – and is undertaken by individuals as well as groups. ‘Culture jamming’ and ‘hacktivism’ have been described as genres of media activism (Lievrouw, 2011). As an example of the pre-history of culture jamming in Australia, I will discuss the anti-tobacco group’s plan to “form a public interest group that would provide an uncompromised alternative media voice to the staid and cautious equivocations of government officials” (Chapman, 1996: 179). I argue that not only does culture jamming have distinct precursors in the form of older forms of activism but that BUGA UP is an important part of that history despite its “one medium bias” (Treré, 2011: 1). In order to fully understand the contemporary movement’s “interaction with a complex information ecology” where “different technologies co-exist and co-evolve” (ibid), I believe it is important to historicise BUGA UP’s early version of activism in the context of current media scholarship.

The term ‘culture jamming’ began to enter the mainstream lexicon in 2000 when Naomi Klein’s best-selling book No Logo was first published. The book appeared at a time when large public protests were occurring around the world at major international forums. As Australian media studies academics John Pace and Jason Wilson noted in the introduction to the M/C journal Logo:

In what was dubbed a ‘year of global protest’ from the Providence Phoenix to the Socialist Review, Klein’s book seemed to offer a story that lent coherence to what was otherwise seen as a bewilderingly heterogenous movement (2003, para 1).

The term itself is generally thought to have been coined by the US band Negativland in 1984 and came into wider use when US theorist Mark Dery used it in an essay published as a 1993 Open Series pamphlet titled Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing and Sniping in the Empire of Signs. Dery explains culture jamming as a practice that mixes art, media, parody and the outsider stance to subvert mainstream media and politics.

The field of culture jamming studies is recent and comparatively small within the wider discipline of media studies. Naomi Klein (2000), who describes herself first and foremost as a journalist, and Kalle Lasn (1999), co-founder of The Media Foundation in Vancouver, Canada, the self-proclaimed world headquarters of culture jamming established by a loose network of activists who publish the monthly magazine Adbusters, were arguably the most prominent self-styled ‘experts’ when it came to describing the phenomenon when it first emerged in popular debate. In scholarly debate, media and cultural theorists including Dery (1993), Downing (2001), Atton (2002), Scalmer (2002) and Meikle (2002) focused specifically on culture jamming in their academic texts of the same period.

In his book Radical Media: Rebellious Communication and Social Movements, the US media studies scholar John Downing (2001) situates culture jamming alongside street theatre, describing it mainly as pranking or politically active art. US media studies academic Chris Atton (2002) briefly discusses culture jamming in Alternative Media, describing it mainly as guerrilla semiotics which “seeks to unmask hypocrisy and the corporate ideology behind advertisements” (p. 44). More recently, in Alternative and Activist New Media, Leah A. Lievrouw (2011) discusses how the convergence of networked media and information technologies “have helped generate a renaissance of new genres and modes of communication and have redefined people’s engagement with media” (p. 1). She describes culture jamming as one of five genres of contemporary alternative and activist new media, the other four being alternative computing, participatory journalism, mediated mobilisation, and commons knowledge. In her article “Pranking Rhetoric: ‘culture jamming’ as media activism”, Christine Harold (2004) argues that culture jammers use pranking as a strategy of rhetorical protest. Jennifer A. Sandlin and Jennifer L. Milam (2008) focus on the anti-consumer actions of two culture jamming groups, Adbusters and Reverend Billy and the Church of Shop Stopping in ‘“Mixing Pop (Culture) and Politics”: Cultural Resistance, Culture Jamming, and Anti-Consumption Activism as Critical Public Pedagogy’. They propose:

… that when viewed as critical public pedagogy, culture jamming holds potential to connect learners with one another and to connect individual lives to social issues – both in and beyond the classroom (2008: 23)

Finally, Asa Wettergren (2009) looks at the meaning of fun in protest in the context of culture jamming as part of contemporary social movement protest in general.

Advances in computer technology have of course shaped the way today’s activists communicate with each other and the manner in which they protest: consider the way the introduction of offset printing in the 1960s led to activists taking advantage of their ability to create publications cheaply and quickly. Today, thanks to the internet, representatives from different groups and individuals from all over Australia were able to form a particularly diverse group to make up the s11 alliance in time for the three day WEF forum in Melbourne in 2000. Members of the Zapatistas, a network of grassroots social activist groups from around the world who use the internet to promote the struggle of the indigenous people of the Chiapas in Mexico, are located all over the world and generally only meet in cyberspace. One of the most recent examples of such a global network is the Occupy Movement, the leaderless protest made up of grassroots organisations and individuals that began in 2011 as Occupy Wall St in New York in the US, protesting against the operation of the global financial system. The movement quickly mobilised across the US before protests against social and economic inequality began occurring internationally. 3

Spray it

BUGA UP held its first public meeting in Sydney in October 1979. Despite the fact that it was poorly advertised, over 50 people attended. Those who were already members showed slides and discussed their work. After the meeting, having doubled the numbers of the group, BUGA UP launched their first organised ‘offensive’ − the BUGA UP Summer Offensive. The plan was to place graffiti on all tobacco and alcohol billboards on government property in Sydney − several hundred billboards. On the official BUGA UP website, original member, (and co-inventor of the Fairlight synthesiser), Peter Vogel says that the group, made up of health professionals, parents and others happy to be known as activists, felt the hypocrisy of the NSW State Government of the time [in 1980] to have been particularly intolerable. He noted:

… [i]ts own Health Commission recognises that up to 40 people per day in Australia die from tobacco and alcohol related diseases. Each year, the Health Minister outlays millions of dollars (taxpayers’ money) on caring for those suffering these diseases. Yet over 50 per cent of tobacco and alcohol billboards and posters are on government property – railway stations and on the sides of buses (http://www.bugaup.org/).

Vogel was responsible for setting up the official website and, at the time of writing, is still responsible for its maintenance.

The official website notes how during the course of the Summer Offensive, graffiti such as “Health and Transport Ministers − the Real Drug Pushers”, “P.T.C.* Promotes Terminal Cancer”, and “Government Kill-boards”, highlighted the contradictions of tobacco-related disease and the State Government’s apparent willingness to support cigarette advertising. They also sought to embarrass the government which claimed to be, as then-premier Neville Wran told ABC radio, “actively discouraging the use of any drug”.

The public support that emerged from the Summer Offensive prompted BUGA UP to establish an official postal address in February 1981, as well as what they called a ‘fighting fund’. Through an appeal in a national weekly newspaper, and by using several blank billboards, they called for financial help. Cheques ranging from $1 to $100 were sent. The money was used to buy equipment, publish material such as pamphlets, and to pay half the fines of any graffitist unable or unwilling to go to gaol. The website makes a point of stating that money sent to the Fighting Fund is not used to pay for legal representation. The members of BUGA UP were among the first real Australian “jammers”, engaging in a consumer versus corporation dialogue before many of today’s activists could press buttons.

On the 23rd August 2003, a number of the original members of BUGA UP gathered for a reunion, 20 years after they had defaced or “improved” cigarette ads on billboards. BUGA UP spanned the years 1978 to 1994, before tobacco billboards were banned. Simon Chapman, an anti-smoking activist and now Professor of Community Medicine at Sydney University, hosted the reunion. He was joined by Peter Vogel, Arthur Chesterfield-Evans, now a surgeon and a member of the Australian Democrats, Ric Bolzan, now a graphic artist at the NSW Heritage Council, and a few others.

Dr. Arthur Chesterfield-Evans joined BUGA UP in the early 80s after seeing deaths related to smoking in his line of work as a doctor. Peter Vogel had a personal motivation – his father had suffered two heart attacks due to smoking. Vogel told me that the campaign was to use humour to get the message across, and he believes that is this is why it was so successful. Vogel states on the website that billboard advertisements are “one way communication” yet individuals, without corporate resources, have no effective right of reply if they object to the way products are promoted or the products themselves.

Instead, the companies are free to regulate themselves and do so in their own interest. For example, it took almost two years legal lobbying of the industry’s self-regulatory council before it deigned to remove Paul Hogan (an acknowledged children’s idol) from Winfield ads. However, true to form, it took this same council only ten days to remove the State Government’s Healthy Lifestyle promotions following a complaint from a tobacco company’s advertiser. It’s enough to make you want to paint on a billboard and BUGA UP their system.

Vogel explained that, in BUGA UP’s opinion, billboard graffiti begins a process of two-way communication, “creating a dialogue where before there was only an instruction or threat that if we didn’t live their lifestyle of booze, fags and mass consumption we were somehow inadequate” (Deitz, personal communication 24th Sept, 2003).

The BUGA UP catalogue/website explains how members critiqued some of the tobacco and alcohol advertisements from early 1980s:

Sterling invites us to join the elite world of the ‘idol’ rich − the cigarette for the person who has (or is that wants?) everything. You know, those little everyday comforts, like the Ferrari with the 250kph capacity for those beastly peak-hour traffic jams on the Harbour Bridge; the ocean-going yacht for your Sunday perve at Lady Jane Beach; and of course, the glider for doing the weekend shopping (http://www.bugaup.org/publications/BUGAUP_Catalogue_1981.pdf)

And:

The introduction of LA (Low Alcohol) beer was heralded by the breweries as a gesture of their responsibility to the community. We were promised there would be fewer drink-drive accidents and less (or smaller?) beer-guts. Instead Tooths turned social responsibility on its head in the quest for bigger profits. “You Can Stay With Tooths LA” we were told – “Pay More, Piss More, Spew the Same” as the refaced billboard soon read. Prove your ocker manhood by being a stayer. No need to feel any more guilt about “one more for the road” − Tooths has said it’s OK (http://www.bugaup.org/publications/BUGAUP_Catalogue_1981_Text.pdf).

BUGA UP was not content simply to gain publicity and therefore potentially more members, they wanted to affect policy. To put the work of BUGA UP into some sort of perspective, it is worth noting that in Australia in the 1960s, nearly 60 per cent of men and 30 per cent of women in Australia smoked, while by 2002 daily smoking by adults had fallen to under 20 per cent for the first time and “shows no sign of having bottomed out” (Chapman, 2002, 661).

In an article for the Medical Journal of Australia, University of Sydney’s Professor Simon Chapman (2002) stated that national death rates from coronary heart disease fell by 59 percent in men and 55 percent in women between 1980 and 2000, in large part because of changes in risk factors like smoking. In the late 1970s, Chapman worked as a community health educator employed by the NSW Health Commission. In 1978, along with a few colleagues, he formed MOP UP – Movement Opposed to the Promotion of Unhealthy Products. They released a press release and were described by The Sydney Morning Herald as the “latest pebble in the shoe of sin industries” (Chapman, 2007, x). Chapman says:

When I first started in tobacco control, people would avoid me at parties as a probable teetotal moral crusader. Mop UP and then especially BUGA UP changed that perception. Understanding that the tobacco industry is a pariah of the corporate world rapidly became a litmus test for a whole set of values about the abhorrence of putting profit above all else (2007, x).

Peter Vogel explained that the members of BUGA UP weren’t influenced by any one set of ideas, and says they were brought together by the fact they all had reasons for being outraged that something like smoking, which causes so much public health damage, was so heavily publicly promoted. “If we had anything else in common, it was that we were all quite environmentally conscious – I took part in the Franklin blockade, for instance – and we shared the feeling that billboards were visual pollution” (Deitz, personal communication, 24th Sept, 2003).

Graffiti, he says, “was one of the few tools we had available to us, and it was affordable. The humour drew attention to the message, and the general public were more sympathetic to us as we were obviously well-intentioned, and entertaining” (Deitz, personal communication, 24th Sept, 2003). Vogel remembers little general creative cooperation or planning, apart from on a social level, when two or three members sometimes went on a graffiti run to keep each other company. He recalls about 100 people involved that he knew of, mainly in Sydney and Melbourne.

When I interviewed Dr. Arthur Chesterfield-Evans, he recalled that when starting out as a doctor, one of his patients (with smoking-related illness) telling him that if smoking really was that bad “the politicians would have done something about it”. As a young doctor, Chesterfield-Evans says he saw many awful deaths due to smoking-related illnesses and it was these deaths, as well as the people left behind, that motivated him to slowly take it upon himself to warn families about the dangers of smoking. He started attending meetings of the lobbying group known as the Non Smokers’ Movement of Australia, which is where he met some members of BUGA UP, and decided to join.

There was no doubt that what BUGA UP was doing was illegal, but I’d been thinking about how ridiculous it seemed that medicine was putting so much work into intensive care when they could target the source – advertising and promoting of smoking. The contrast between the BUGA UP guys who said “we might get arrested but it’s worth it if we make a difference” and those doctors who were happy making money from surgery was marked. It became not a question of whether I should, but whether I was courageous enough (Deitz, personal communication, 21st Sept, 2003).

Chesterfield-Evans was arrested a few times but says he recognised how he could become a public face for BUGA UP, having seen the effects of smoking on people first hand.

Member Ric Bolzan was once arrested at the Art Gallery of NSW after chaining himself to a Marlboro-sponsored racing car parked in the foyer of the gallery. His supporters showered the car with cigarette butts. It took a while for gallery staff to realise, he says, that he was not part of the show but was protesting against the Philip Morris sponsorship of an exhibition. He was “bundled into a paddy wagon and charged with malicious injury and causing serious alarm and affront.” Bolzan defended himself in court and won, telling the magistrate that people went to art galleries to be alarmed and affronted (Lawson, 2002).

When the Phillip Morris tobacco conglomerate ran a competition to find a real life Marlboro man, BUGA UP entered a poster of an older man who breathed through a hole in his throat, and changed the caption “Marlboro Man” to “Marble Row”. The BUGA UP website notes that while members are fighting companies whose operations span continents, and whose annual turnover rivals the gross national product of many countries, the power of the consumer should not be overlooked. “For example, it has been calculated by the NSW Health Commission that if every smoker gave up one cigarette per day, it would cost the tobacco companies $40 million per year”. Between and including the years 1981 and 1983 (“and many thousands of billboards”) 21 BUGA UP members were arrested. Only 13 of these were convicted of “Willful Deface” or “Malicious Injury” (to a billboard) (BUGA UP, 1981).

What about the Malicious Injury to community health and the Willful Deface of our visual environment caused by billboard promotions? Neither the government nor the law courts will answer this question. While they continue to protect corporations by their silence, ordinary people like us will be forced to speak up – on the billboards … (BUGA UP, 1981).

Vogel notes that some anonymous advertisers in Sydney and Melbourne committed $75,000 worth of advertising space and skills to the Lions Club “Speak Up Against Vandalism” campaign. The manager of a major outdoor advertising company, Australian Posters, stated that their contribution to the “Speak Up” campaign was a response to the “unwarranted publicity our friends from BUGA UP have been getting”. Those “Speak Up” posters, explains Vogel, were then placed predominantly on sites leased by tobacco and alcohol companies.

The BUGA UP website points out that painting only one billboard per week costs the corporation responsible for the advertisement between $500 and $5000 per year, depending on your thoroughness. It’s a sad fact, but we’ve learnt through long experience that money is the only language billboard advertising companies understand. Nothing will get those ads down faster than if their profits are reduced by escalating maintenance costs.

But even more important than this financial factor is the effect that the refaced ad will have on those who read it. At the very least you’ll be Speaking Up for Community Health – something none of our governments seem to care much about (http://bugaup.org/howto.htm).

Culture shock

The role consumer goods play in our culture has of course, expanded significantly since BUGA UP held their first meeting. What is also new is the way in which activists have chosen to protest against what they see as self-serving institutions – government, big business and mainstream media – and the impulses behind their protest, one impulse being a need to criticise the corporate influence over our everyday lives. Another is a desire to aggravate, rather than overthrow, the status quo. What the movement is doing is creating possibilities for a range of responses, including non-traditional political participation. And while today’s culture jammers are determined to advance their own political or social causes, unlike BUGA UP, being publicised by the mainstream media is not always high on their agenda. Rather, many jammers have developed their own media channels and are determined to create their own public space.

Writers Luther Blissett and Sonja Brünzel describe the larger context of the practice of culture jamming this way:

Culture-jamming for many is an entire way of living. Its advocates generally reject the notion of the citizen as merely consumer, and the idea of society as merely marketplace. The culture jammer and media activist approach to life questions the underlying social relations which govern the place of media (and by extension, capital) in our culture (cited in http://students.english.ilstu.edu/bmthake/ident/culturejam.html).

The Luther Blissett project has been explained as follows: “s/he is a multiple single, a multi-use virtual reputation, a name anyone can use”. The name is taken up by activists, artists and others (see http://www.LutherBlissett.net).

Kalle Lasn agrees:

Culture jamming is a way to fight back against advanced consumer capitalism. I see the kind of consumer culture that we have built up over the last many years as being unsustainable. It’s a culture that drives the global economy in a way that will eventually make it hit the wall. Culture jamming is a way to get this dysfunctional culture to bite its own tail (quoted in Meikle, 2002:132).

There seems to be a politicised refusal amongst culture jammers to submit to a culture they believe is controlled by the corporate class. As jammers resist this role, reclaiming rather than forfeiting space, they create what Naomi Klein calls “a climate of semiotic Robin Hoodism” (2000: 280). Jammers are engaged and complicit, finding cracks in ‘corporate society’ and working these to their advantage, what Canadian cultural theorist Linda Hutcheon (1989) calls subversion from within.

Another major difference between the members of BUGA UP and today’s activists is the way they frame the role of media consumers. In comparison, BUGA UP’s critique of the relationship between billboard advertising and consumer behaviour, with the benefit of hindsight, can seem simplistic, anchored as it is to a passive audience frame of reference. The members of BUGA UP assume advertising itself has a incredible power over the average citizen, with Simon Chapman (1989), for example, stating in the Medical Journal of Australia a direct correlation between the fall of national death rates and the changes in risk factors such as smoking due to BUGA UP’s advocacy. Contemporary activists tend to adopt a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between media production and consumption.

Some BUGA UP members, it could be argued, adopt a somewhat paternalistic and arguably authoritarian position in relation to consumers, who they tended to frame as potentially uneducated and passive in the face of media messages – as a group who are easily duped. For example, when commenting on the action of civil disobedience groups as significant in contributing to anti-smoking policy, Chapman (2001) describes them in the journal Health Education & Behaviour as “seeking to advocate on behalf of children and tobacco victims” (my emphasis). But while there was certainly some evidence of a paternalistic view towards consumers in the interviews I conducted, other members saw BUGA UP emphatically as an anarchistic organisation. Chesterfield-Evans notes that BUGA UP was:

… seriously anarchic – we were all certain about what we were willing to do, what we were willing to be arrested for, and what we were willing to say when we were arrested. We got two bites of the cherry – when we graffitied billboards people saw them and laughed, and then we got another bite when we were taken to court (Deitz, personal communication 21st Sept, 2003).

Chesterfield-Evans told me he was sure BUGA UP was the first group to perform such social vandalism. He says:

When I took my anti smoking ideas to a conference in Canada in 1983 there were mostly Americans there and no-one mentioned that there was anything similar to BUGA Up in Canada or America. I think we took it to them (Deitz, personal communication 21st Sept, 2003).

Vogel agrees:

We weren’t aware of the work of the Billboard Liberation Front in San Francisco until BUGA UP had been around for a while. I don’t think they were nearly as prolific as BUGA UP (Deitz, personal communication 24th Sept, 2003).

While Peter Vogel asserts that BUGA UP were a diverse group with no single political manifesto, interviews with original members of the group and an examination of the BUGA UP archive, reveal certain ideological principles. For example, they believed advertising was both one-sided and extremely powerful. Peter Vogel speaks of individuals having no right of reply to billboards, yet also seems to assume that everyone who comes into contact with billboards will not only notice them but be directly influenced by them. Simon Chapman speaks of the fall in death rates from coronary heart disease and relates this to changes in risk factors like smoking, which he directly relates to BUGA UP’s advocacy work. Arthur Chesterfield-Evans refers to advertising and the promoting of smoking as the source of the problem of smoking-related illnesses and subsequent deaths.

All key BUGA UP members believe strongly in the power of the mainstream media to directly sway opinion. Chesterfield-Evans talks about taking “two bites of the cherry” – the reaction to graffitied billboards being one, and the reaction when they were taken to court being the other. The more journalists there were, he believed, the more often their argument would be run in the mainstream media. Simon Chapman nominates the articles he has written for newspapers and the times he has been interviewed for television and radio as his most influential work.

Chapman states that Australia has one of the world’s most successful records on tobacco control, and that the role of public health advocacy in securing public and political support for tobacco control legislation, policy and program support, is widely acknowledged in WHO policy documents. Indeed, he notes, it is not only health advocates that think so, consider the following except from a Philip Morris (Australia) Corporate Affairs Planning Document. 4

Chapman argues that, by moving the definition of radical into civil disobedience, what had been considered radical became moderate by comparison. It became routine policy for many health agencies to call for a total advertising ban when previously such groups had been hesitant to do so.

While there can be little doubt about the positive advocacy work performed by BUGA UP, their assumptions about audience arguably fit neatly into traditional left wing criticisms of the media and advertising (Williamson, 1978: Dyer, 1982; Fowles 1996) and into a framework for understanding media consumption which positions consumers as necessarily powerless and passive. Not only do some members of BUGA UP subscribe to the idea of the youth being targeted by tobacco advertisers as uneducated, non media savvy and easily persuaded, Chapman describes part of the civil disobedience campaign against tobacco companies and their advertisements as work that needs to be done on behalf of other, potentially defenceless victims.

Political and cultural attitudes to media consumption to one side, BUGA UP was a pioneering movement which represented a watershed in media-based forms of activism in Australia. Founding BUGA UP member, Dr. Simon Chapman now has seven researchers working with him at the University of Sydney on a critical history of the tobacco industry as revealed through the industry’s own internal documents. 5

While BUGA UP was forced to use the most rudimentary tools in their campaign to turn the message of cigarette advertisers back on themselves, contemporary culture jammers are often able to use media tools at the same level of sophistication as the very media and goods producers they intend targeting. As witnessed by the material available on BUGA UP’s official website, updated in 2013 to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the banning of billboard tobacco advertising in Australia, it is only the work documented at the time that we are now able to appreciate. Some work only lasted a few hours before it was removed – if it was not documented, it was unseen.

Like the members of BUGA UP, the culture jammers of the new millennium know exactly where and how to target multinational corporations. They also understand the power of profit and exactly how important brand power and image is to such corporations (Klein 2002). What is different about today’s culture jammers, however, is that they don’t necessarily want to be part of the solution. Like BUGA UP, activists want to highlight and expose what they see as the excesses and hypocrisies of corporations and advanced capitalism, but unlike BUGA UP, who arguably wanted to take on the State, many culture jammers are content to forge a new or separate space, a sphere alongside the recognised public sphere that, if not free from corporate salvos and consumer messages, has room for acknowledgement of diversity and dissent.

Links

BUGAUP channel on YouTube

BUGAUP website

Notes

1 The group Movement Opposed to the Promotion of Unhealthy Practices (MOP UP) pursued a complaint that led to comedian Paul Hogan being removed from Winfield advertisements due to his popularity with children, see Chapman, S. (1980). A David and Goliath Story: tobacco advertising in Australia, BMJ 1980; 281:1187-90

2 See Downing, J. et al, (2001) Radical Media: Rebellious Communication and Social Movements, Sage; Atton, C, (2001) Alternative Media, Sage; Lievrouw, A, (2011) Alternative and Activist New Media, Polity.

3 For more details about the Occupy Movement, see Overland’s Online Occupy issue, published 30 January 2012.

4 In the article Tobacco control advocacy in Australia: reflections on 30 years of progress written for the journal Health Education & Behaviour, Chapman explains how, in the past three decades, Australian tobacco control advocates have made significant gains. Along with harm reduction (testing tar and nicotine content of cigarettes in order for tobacco products to be regulated); advertising bans; warnings on packs; and mass reach campaigns, and other points, Chapman lists the action of civil disobedience groups as significant in contributing to anti smoking policy:

Australia was the first nation to experience widespread civil disobedience against the tobacco industry through a campaign where health and community activists graffitied tobacco billboards. This effort dramatically reframed tobacco advertising from something most would have seen as an unremarkable, normal part of the commercial environment into a phenomenon that focussed community discourse about irresponsible industry and collusive government policy unwilling to restrain it.

and,

Some of the highlights of advocacy to end all tobacco advertising in Australia include: A six year, Australia wide civil disobedience billboard graffiti campaign where doctors, teachers and ordinary citizens risked jail terms, but were mostly given token fines by courts and widespread news coverage. This protracted campaign, involving no more than 50 people, probably did more than any other advocacy initiative to transform the popular understanding of tobacco control from being a puritanical exercise … to one that embodied values about citizens seeking to advocate at considerable risk to their careers on behalf of children and tobacco victims.

5 Excerpt from a Philip Morris (Australia) Corporate Affairs Planning Document:

Australia has one of the best organised, best financed, most politically savvy and well-connected anti-smoking movements in the world. They are aggressive and have been able to use the levers of power very effectively to propose and pass draconian legislation. … The implications of Australian anti-smoking activity are significant outside Australia because Australia is a seedbed for anti-smoking programs around the world.

And,

Australia is a laboratory for the global anti-smoking network. Both anti-smoking policies and the individuals who promote them are exported from Australia and simulate anti-smoking activities worldwide.

References

Atton, C. (2002). Alternative Media London: Sage

Blissett, L. & Brünzel, S. (2002). What About Communication Guerrilla? Available from http://www.sniggle.net/Manifesti/blissettBrunzels.php

BUGA UP (1981). Not a group – A movement Retrieved 1st May 2014 from http://www.bugaup.org/publications/BUGAUP_Catalogue_1981.pdf

Bennett, A. & Robards, B. (2012): Editorial, Continuum: Journal and Media & Cultural Studies 26:3, 339-341

Chapman, S. (1996). Civil Disobedience and Tobacco Control: the case of BUGA UP Tobacco Control Vol. 5, 179-185

Chapman, S. (2001). Tobacco Control Advocacy in Australia: Reflections on 30 Years of Progress Health, Education and Behaviour June 2001, Vol. 28, No. 3 274-289

Chapman, S. (2002). Agent of change: more than “a nuisance to the tobacco industry” Medical Journal of Australia 177 (11) 661-663

Chapman, S. (2007). Public Health Advocacy and Tobacco Control: Making Smoking History Melbourne: Blackwell Publishing

Culture jamming and e-literature Available from http://students.english.ilstu.edu/bmthake/ident/culturejam.html

Deitz, M. (2003). Personal communication with Arthur Chesterfield-Evans, 21st September 2003

Deitz, M. (2003). Personal communication with Peter Vogel, 24th September 2003

Deitz, M. (2003). Personal communication with Simon Chapman, 24th September 2003

Dery, M. (1993). Culture jamming: Hacking, slashing and sniping in the empire of signs. (Open Magazine Pamphlet Series, 1993) Available from http://web.nwe.ufl.edu/~mlaffey/cultjam1.html

Downing, J. (2001). Radical media: Rebellious communication and social movements. California: Sage Publications.

Dyer, G. (1982). Advertising as communication London: Routledge

Fowles, J. (1996). Advertising and Popular Culture Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications

Harold, C. (2004). Pranking Rhetoric: ‘culture jamming’ as media activism. Critical Studies in Media Communication. Vol. 21, issue 3, pp.189-211

Hutcheon, L. (1989). The Politics of Postmodernism London: Routledge

Klein, N. (2000). No Logo London: Flamingo

Lawson, V. (2002, 12 Oct). No ifs, no butts – these boys were tough Sydney Morning Herald Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/10/11/1034222596319.html

Lievrouw. L. (2011) Alternative and Activist New Media Cambridge: Polity Press

Meikle, G. (2002). Future Active: Media Activism and the Internet New York: Routledge

Pace, J. & Wilson, J. A. (2003, Jun 19). (No) Logo Au-go-go . M/C: A Journal of Media and Culture, 6, Available from http://www.media-culture.org.au/0306/01-editorial.php

Sandlin, J.A. & Milam, J.L. (2008). “Mixing Pop (Culture) and Politics”: cultural resistance, culture jamming and anti-consumption activism as critical public pedagogy. Curriculum Inquiry, 38: 323-350

Treré, E. (2011). Studying media practices in social movements CIRN Prato Community Informatics Conference 2011 Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/1234227/Studying_media_practices_in_social_movements

Wettergren, A. (2009). Fun and Laughter: Culture Jamming and the Emotional Regime of Late Capitalism Social Movement Studies, Journal of Social, Cultural and Political Protest 8:1, 1-0

Williamson, J. (1978). Decoding advertisements: ideology and meaning in advertising London: Boyars

About the author

Milissa Deitz is a Lecturer in Communication and Media Studies in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts – University of Western Sydney, and a member of the Writing and Society research group. She holds a PhD in Communication (2006) from the University of Sydney, a Master of Arts in Cultural Studies (1998) from Macquarie University and a Bachelor of Communication (1993) from the University of Newcastle. She is an assistant editor of Global Media Journal: Australian Edition and co-hosts the book show Shelf Life on TVS (channel 44) which is supported by UWS. Dr. Deitz worked as a journalist for 15 years before moving into academia full-time. Her books Bloodlust (1999) and My Life As A Side Effect (2003) are both published by Random House. The academic crossover text, Watch This Space: The Future of Australian Journalism, is published by Cambridge University Press (2010). She is currently working on a second novel.