Narratives used to portray in-group terrorists: A comparative analysis of Israeli and Norwegian Press

Tal Samuel-Azran

The Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya, Israel

Amit Lavie-Dinur

The Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya, Israel

Yuval Karniel

The Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya, Israel

Abstract

Studies have found that US media persistently ‘repair’ conflicting images of in-group (Christian and Jewish) perpetrators of crimes that fit the definition of ‘terrorism’ to conform to the conventional narrative that terror is the realm of Muslims. To evaluate whether this practice extends to other democracies, we examined Israeli press coverage of attacks against Palestinians by Jewish settlers (n =134) and Norwegian press coverage of attacks against ‘liberal’ targets by Christian extremist Anders Breivik (n =223). Content analysis reveals that Israeli and Norwegian press labeled in-group perpetrators as “terrorists” and their acts as “terrorism”. Based on comparative politics literature, we suggest that the Israeli and Norwegian journalists did not “adjust” the portrayal of in-group perpetrators due to the pluralistic worldview that characterizes journalists operating under a multiparty system. Furthermore, the Israeli press was more critical of the authorities for failing to prevent the crimes, compared to the Norwegian press, supporting the typology of multiparty systems suggested by Sartori (1976).

Introduction

The US State Department’s definition of terrorism is very specific

…premeditated, politically-motivated violence perpetrated against non-combatant targets by sub-national groups or clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience (Title 22 of the United States Code, section 2656f (d)).

However, not all crimes that fall within this definition are accorded the same treatment. Despite a general consensus that out-of-state perpetrators of crimes such as Al-Qaeda and Hizbollah are “terrorists” (Norris et al., 2003), studies found that the US media often “repair” the image of in-group citizen perpetrators (e.g., war veterans such as Timothy McVeigh) by shifting attention from their malicious actions to their personal circumstances (DeFoster, 2010; Entman, 2004). The phenomenon of “narrative repair” of in-group perpetrators extends to other countries, including reports of Jewish-Israeli settlers attacking Arabs in Israel, where the media usually emphasizes the Arabs’ contributory role in the attack (Handley, 2009). In contrast to Muslims who are traditionally portrayed as villains aiming to undermine “our way of life and our values”, Jewish and Christian perpetrators are portrayed as individuals who have no control over their actions (Chomsky, 1992; Nacos, 2007). This journalistic practice obviously stands in stark contrast to the professional norm of impartiality and has major societal implications, from punishments imposed on the perpetrators by the courts (Norris et al., 2003) through the appearance of copycats, to influence on public opinion about the legitimacy of the crime (Nacos et al, 2011). The representation of in-group perpetrators is also highly revealing of journalists’ endorsement of an ‘us/them’ dichotomy, particularly the differences between ‘our values’ versus ‘their values’.

This study examines whether the US journalist practice of routinely ‘repairing’ the image of in-group perpetrators extends to other democracies, using Israel and Norway as case studies. The need for a comparative perspective stems from the global rise in attacks by in-group perpetrators against out-group targets, attributed to the availability of explosive information on the Internet, copy-cats, the growing number of anarchist movements, and the spread of anti-Muslim sentiments in the West. Specifically, the 2011 attacks by Anders Behring Breivik in Norway illustrate the prevalence of this phenomenon: even the most peaceful countries are not immune to such attacks. Accordingly, we examined Norwegian media coverage of Breivik’s attacks that left 77 people dead and were considered the most brutal act of aggression committed on Norwegian soil since the Second World War.

Our second case for analysis is Israel, where violent attacks by Jewish settlers against Palestinians have been on the rise since the beginning of the century (Pepper, 2010). We examined the three highest-profile cases where the alleged perpetrators were arrested by Israeli authorities between 2005 and 2010. The comparative analysis between Israeli and Norwegian press and the subsequent comparison to the US press coverage of in-group perpetrators is an initial attempt to map journalistic practices and heighten our awareness of the different labeling practices and their underlying motivation across countries and political systems.

Case studies

This study compares Israeli and Norwegian press portrayals of in-group attacks that fall within the definition of US State department definition of terrorism. In our analysis of the Israeli press, we examined press coverage of attacks committed by three right-wing Jewish perpetrators against Palestinians. In the first incident, Eden Nathan-Zada, an extreme right-wing Jewish settler, shot to death four Arabs in a bus full of Arabs in August 2005, in an attempt to stop Ariel Sharon’s disengagement plan from Gaza. Importantly, the attack occurred shortly after the Second Palestinian Intifada (the Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule, which began in late September 2000 after Ariel Sharon’s controversial visit to the Temple Mount and ended in 2005 with an estimated death toll of 5,500 Palestinians and over 1,100 Israelis). Throughout the Intifada, the conventional narrative in Israeli media had been that Jews are victims of Palestinian terrorism, but never vice versa: Israeli attacks against Palestinians were consistently labeled acts of retaliation (Dor, 2001).

The second case study is the coverage of the act by Jack Teittel, a US-born extreme right-wing Jewish settler who was charged in November 2009 with murdering of two Palestinians in 1997. Teittel was originally pronounced by the court as being mentally unstable and unfit to stand trial, but in December 2011 he was pronounced mentally fit to stand trial and he is currently awaiting his verdict. The third attack was committed by extreme right-wing Jewish settler Haim Perlman, who was arrested in July 2010 on suspicion of committing several stabbing rampages in 1998 and 1999, killing three Palestinians. Perlman was released to house arrest since August 2010 and he is currently awaiting trial.

In our analysis of the Norwegian media, we examined Anders Behring Breivik’s July 22, 2011 attacks. Driven by extreme right-wing ideology (according to a manifesto written and sent to the press before his attacks),Breivik’s bombed government buildings in Oslo, an attack which resulted in eight deaths. Subsequently he went on a shooting spree at a camp of the Workers’ Youth League (AUF) of the Labour Party on the island of Utøya where he killed 69 people, mostly teenagers. Altogether, the two deadly violent attacks left 77 people dead. On August 24, 2012, he has been sentenced to at least 21 years in prison after a court declared he was sane throughout his murderous rampage.

Journalistic practices in the representation of ideologically-motivated crimes

Tuchman (1973) argued that in light of the overwhelming pressure to routinely process and report unexpected events, journalists locate and present these events within a limited number of ‘typifications’ that fit the general public’s narratives. Subsequent studies confirmed her assertions about the modus operandi of journalists (e.g., Bird & Dardenne, 1988; Carey, 1992; Lule, 2001; Schudson, 1989; Van Gorp, 2007). Importantly, Berkowitz (2005) found that when reality does not conform to traditional mythologies, reporters “revise” these traditional narratives to describe the attack. Thus, whereas the world media portray male bombers negatively, Palestinian women perpetrators were described as “seeking justice” and the attacks were portrayed as “heroic”, in accordance with the Woman Warrior myth.

According to Topo (2006) and Altheide (2006; 2009), defining events such as the 9-11 attacks, triggering the pervasiveness of the term “terror” in everyday life, promote a “narrative revision” of the portrayal of in-group perpetrators of school shootings, from “mass murderers” to “terrorists”. Their studies reveal that whereas the Columbine events were widely termed as a “massacre”, similar events that occurred after 9-11 were often portrayed in court and the media as “terror”. However, their findings apply to criminal activities rather than to ideology-driven crimes, which is the subject of this study.

Indeed, scholars identified that US journalists do not update or ‘revise’ traditional narratives when the perpetrators hold an ideological manifesto. According to one argument, since the 1972 Palestinian Liberation Organization terror attack in Munich and the 1979 Iran Hostage Crisis, the US media are fixated on the ‘Muslims = terrorism’ notion, and the dominant depictions of ‘terrorist’ in the news media are always of Arab Muslim extremists (Atkin & Fife, 1993; Norris et al., 2003). DeFoster’s (2010) study of coverage of post-9/11 domestic terror events in the US on evening network news broadcasts found that attacks carried out by culprits who were identified as “Muslim” were systematically more likely to be labeled “terrorism” than those in which news coverage did not identify the religious identity of the culprit. Nacos (2007) also contend that in the US there are no “Christian” or “Jewish” terrorists. To illustrate, in the hours following the Oklahoma bombing which killed 168 people (including federal employees) and injured more than 500 others, the media framed the incident as an act of terror committed by a Muslim, but when the perpetrator turned out to be a decorated Gulf War veteran of European descent, the crime was re-framed as the act of an evil mad man who acted alone (Entman, 2004; Vidal, 2001). In the case of Ted Kaczynski (“the Unabomber”), who sent sixteen letter bombs that killed three persons and injured 23 others, the US mass media even gave the perpetrator an opportunity to make his case to the public when he was interviewed by Time magazine and elaborated on his anti-technology attitude that motivated his actions (Nacos, 2007). Handley (2008; 2009) noted that the same practice extends to violent attacks by Jewish-Israelis against Arabs. By focusing on the fact that Jewish settlers commit the crimes on Arab territory and by diverting attention to Jewish fears of Arab retaliation and violence, journalists restored the dominant images of ‘Jew-as-victim’ and ‘Arab-as-aggressor’ (Philo & Berry, 2004).

Comparing Israeli and Norwegian media

Comparative studies noticed that the main difference between media across democratic systems is the political system under which they operate. Specifically, studies showed that the structure of the party system can explain systematic biases across media systems (e.g., Hallin & Mancini, 2004; Sheafer & Wolfsfeld, 2009). While the US media, which regularly ‘repair’ the image of in-group perpetrators, operate under a high-consensus two-party system, Israeli and Norwegian media operate under a more pluralistic multiparty system. Based on a longitudinal content analysis of Israeli journalists’ modi operandi during political conflicts, Wolfsfeld (1997) argues that the healthy competition between administration and antagonists over access to the Israeli media can be attributed to the country’s pluralistic system. For example, after extreme right-wing member Baruch Goldstein killed 33 Palestinians in 1995 in an attempt to stop the Oslo Accords, Israeli press gave extremist groups an opportunity to explain the massacre and their motivations, despite these groups’ lack of resources, low status, and attempts by the Israeli government to frame them as “fanatics”.

There is, however, an ongoing debate regarding the boundaries of pluralism in Israel, as scholars concur that under threats such as war and the Intifada, pluralism stops and the media rally “round the flag” (Dor, 2001; Neiger & Zandberg, 2004). According to several studies, the dominant narrative during the Intifada, in which the highly moral Israeli army portrayed as the victim was forced to respond to Palestinian brutality, ignored the link between the Israeli army’s aggressive responses and the perpetration of the cycle of violence (Dor, 2001; Korn, 2004; Neiger & Zandberg, 2004; Wolfsfeld, Prosh & Awabdy, 2008). Nonetheless, Kampf and Liebes (2009) argued that in comparison to the media’s demonization of Palestinians and depersonalization of Palestinian casualties during the first Intifada (1987-1991), during the Second Intifada the Israeli media often described a more nuanced picture of Palestinian society.

According to the Global Terrorism Database (http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/), which has been recording terrorist attacks since 1970, only 15 terrorist attacks occurred in Norway between 1970 and Breivik’s 2011 attack, resulting in a total of one person dead and 13 wounded. According to the same database, 2,776 acts of terrorism were committed in Israel during this period. It is therefore not surprising that numerous studies have addressed Israeli media modi operandi in reporting ideological motivated crimes, while the literature on Norwegian coverage of violent ideological crimes is scarce.

The structure of the Israeli and Norwegian media

When conducting a comparative analysis, the compared media do not have to be identical, although they are required to have a high degree of similarity (Entman, 1991). The Israeli and the Norwegian media share a tradition of a very strong public system. In Israel, the television and radio media were originally based on the BBC model, with the aim of educating and shaping Israeli culture (Caspi & Limor, 1999). Israeli radio remains dominated by publically funded stations and competes successfully with commercial radio channels, although public television channels are less popular than the commercial television channels. In Norway, the public media broadcast company Norsk Rikskringcasting (NRK) was launched 80 years ago and remains a source of some of the most popular radio and television shows.

The structure of the media market in both countries has changed in recent decades: private investors and corporations moved to gain control of the media, and the public media system is threatened by the increasing concentration of power in the hands of several moguls and corporations. Increasing concentration is highly evident in the newspaper markets in both countries. In Norway, the three major newspapers account for 55%–60% percent of the total circulation. The Israeli newspaper market is similarly dominated by two newspapers: Yedioth Ahronoth, owned by the Mozes family, and Israel Hayom (Israel Today), a free newspaper owned by casino-owner billionaire Sheldon Adelson.

Finally, newspaper readership in both countries is very high. In Israel, newspaper readership is around 64% of the population. The Norwegian market has one of the highest readerships rates in the world: 550-600 copies are sold per 1,000 inhabitants.

Research questions

In light of all the above, the research questions of the study are:

RQ1: How did the Israeli and Norwegian press label recent in-group perpetrators when reporting their crimes (Eden Nathan-Zada, Jack Teittel, Haim Perlman, and Breivik, respectively)?

RQ2: How did the Israeli and Norwegian press label the acts committed by them?

RQ3: How did Israeli and Norwegian press describe the motivation behind the attacks?

RQ4: Did the media blame the authorities?

Method

To examine the press coverage of the attacks selected for study, we used the content analysis method, defined as “a research technique for the objective, systematic, and quantitative description of manifest content of communications” (Berelson 1952, 74). The method was useful in evaluating use of the terms “terrorism” and “terrorists” versus alternative labels for these crimes and their perpetrators. The coding scheme used for the quantitative content analysis employed 12 variables, including date, length of article, type of article, headline, terminology, criticism of authorities, and motivation for the crime. To test inter-coder reliability, two (Norwegian and Hebrew speaking) coders were trained and given an identical random set of a 100 coding items. After a pilot test (of 25 items), the coding scheme was modified and a second reliability test was performed. According to this reliability test, Scott’s Pi was 86% for the category with the lowest rate of agreement (“motivation for the crime”). In addition, we analysed opinion editorials (op-eds) on the attacks and their perpetrators published in the 10 days following each attack.

Sample

The first newspaper we selected for the analysis is Israel’s elite newspaper Haaretz, widely recognized as representing left-wing ideology (Slater 2007). Thus, to ensure that our media sample represents the full spectrum of political opinions in Israel, the second newspaper examined is the daily right-wing tabloid Israel Hayom (Persiko 2009), sponsored by Netanyahu-supporter billionaire Sheldon Adelson. Currently, Israel Hayom is Israel’s most popular daily newspaper. Israel Hayom was launched in 2007, and was therefore not included in the analysis of Eden Nathan-Zada. The third newspaper included in the study is Yedioth Ahronot, a mainstream daily tabloid controlled by the Mozes family, which was Israel’s highest selling newspaper for three decades until the advent of Israel Hayom. The papers selected represent both broadsheet and tabloid genres: Haaretz is a broadsheet newspaper, and Yedioth Ahronot and Israel Hayom are tabloids.

In total, 134 news stories were collected and analyzed from the Israeli press. The unit of analysis was news articles. In addition, we conducted a separate textual analysis of opinion editorials concerning each attack. In each case, we examined all the articles that appeared in the first 10 days since the attacks: August 5-15, 2004 in the case of Eden Nathan-Zada, November 2-12, 2009 in the case of Jack Teittel, and July 15-25, 2010 in the case of Haim Perlman. In all three cases, the story almost or completely disappeared from the headlines after 10 days.

In Norwegian media, we selected the two most popular daily newspapers: Aftenposten, a spreadsheet with an average circulation in 2010 of around 250,000, and Verdens Gang (VG) a tabloid with an average circulation in 2010 of around 234,000 copies. VG’s long-standing position as Norway’s most popular paper was lost to Aftenposten in 2010. The two papers are by far the main news sources in the country (by comparison, the third largest newspaper, the tabloid Dagbladet, had a dramatically lower circulation of 105,000 in 2010). Both VG and Aftenposten are owned by the same media conglomerate, Schibsted, a leading player in the Norwegian and Swedish media markets. Aftenposten is often regarded as having a social-democratic orientation, as does the majority of Norway’s press, while VG is a non-partisan tabloid. In total, 223 articles were collected and analyzed from the two Norwegian papers (119 from Aftenposten and 104 from VG in the 10-day period following the attack (July 22, 2011-August 1, 2011).

Findings

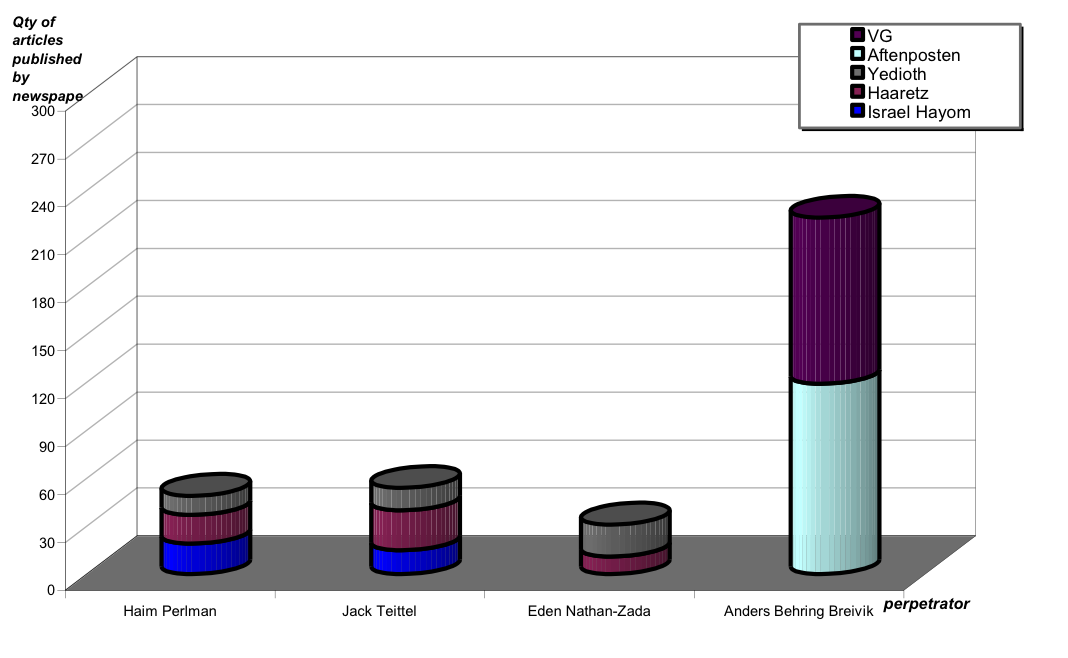

Table 1 (see Appendix) presents the number of articles covering each attack. In Israel, each attack received similar coverage: a total of 15-20 news items in each newspaper in the sample. On the day after each attack, related stories appeared on the first page. All the stories remained in the main headlines for 2-3 days on average, when they were replaced by other news. In Norway, Breivik’s attacks were covered extensively and made the main headlines every day during the 10 days examined, with an average of 15-20 daily news items in each newspaper.

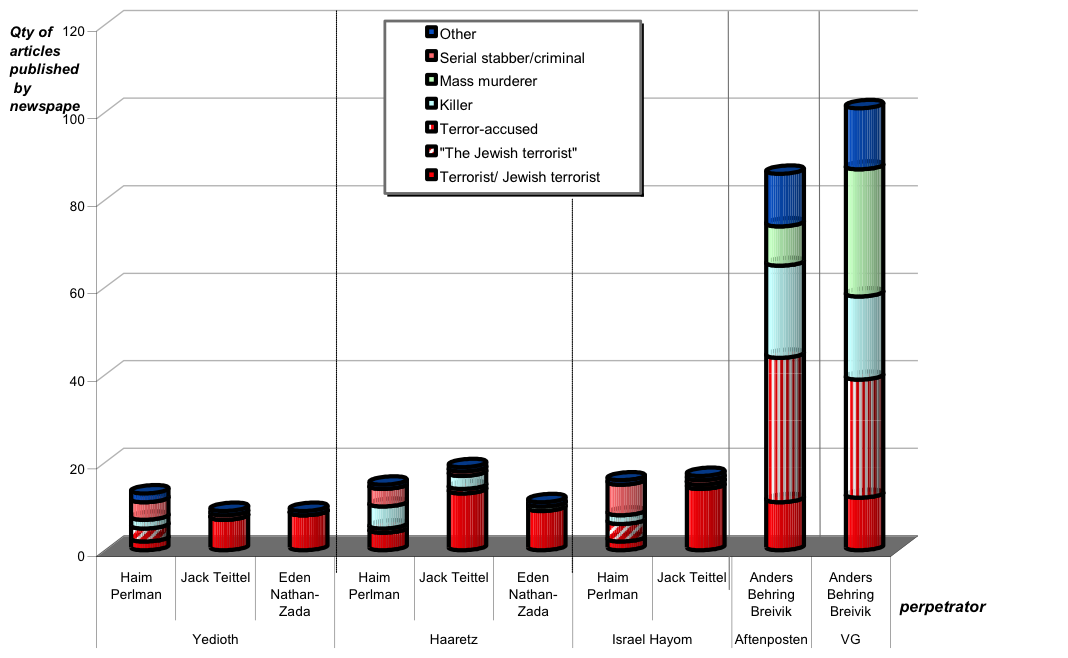

Addressing RQ1, Table 2 (see Appendix) summarizes the terminology used to describe the perpetrators of the attacks. By far, “terrorist” (N = 29) and “’Jewish terrorist” (N = 30) were the most common terms used to describe the perpetrators in Israeli press: The term “terrorist” was used in 59 out of the 109 (54%) references to the person behind the attacks. In an additional eight occasions, the papers referred to the perpetrator as a “Jewish terrorist”.

Of three perpetrators, Nathan-Zada is most frequently described as a “terrorist”. The articles describe him in very graphic terms (e.g., “blood-thirsty”), and express no compassion for the circumstances surrounding the act (e.g., he was lynched to death by the Arab masses after the shooting, he was only 19, etc.). The media also widely emphasized that Rishon Letzion, where he lived before moving to a settlement in the West Bank, refused to bury him: the story was accompanied with headlines such as “No One Wants to Bury the Jewish Terrorist” (Haaretz, August 7, 2005). Several articles focused on his evolution from an ordinary citizen to a “terrorist”, (e.g., “Good Student Turned Terrorist.” Yedioth Ahronot, August 6, 2005). Interestingly, whereas the media showed no compassion towards Nathan-Zada, the newspapers expressed compassion for his Arab victims, describing them as “innocent Israeli citizens” (“Kach Member Kills 4 Arabs.” Haaretz, August 5, 2005) and “Four Bus Passengers from the Most Loyal Section of Israeli Society” (“Jewish Terrorist.” Yedioth Ahronot, August 6, 2005), with little reference to their Arab identity. In addition, reporters dedicated two pages to the victims’ personal lives, an honor typically reserved for Jewish-Israeli victims of Palestinian attacks. The nature of the Arab victims’ life stories were also comparable to the lives of Jewish victims: The story of the two Arab girls who died on the bus and were best friends at school, was accompanied by a the headline featuring a Biblical quote from the story of Saul and Jonathan (Samuel 1:23), “in death they were not parted”.

In a similar manner, Norwegian newspapers Aftenposten and VG referred to perpetrator Anders Behring Breivik most commonly as a “terrorist” or “terror accused” – in 83 out of 187 (44%) references to the perpetrator. When labeling Behring Breivik as “terror-accused”, the newspapers often “explained” that no one had ever been convicted of terrorism in Norway. The terms “terrorist”/”terror-accused” were most commonly used in articles dealing specifically with the bombing that took place in Oslo, while the terms “mass murderer” and “killer” were used primarily in articles on the killings that took place in Utøya.

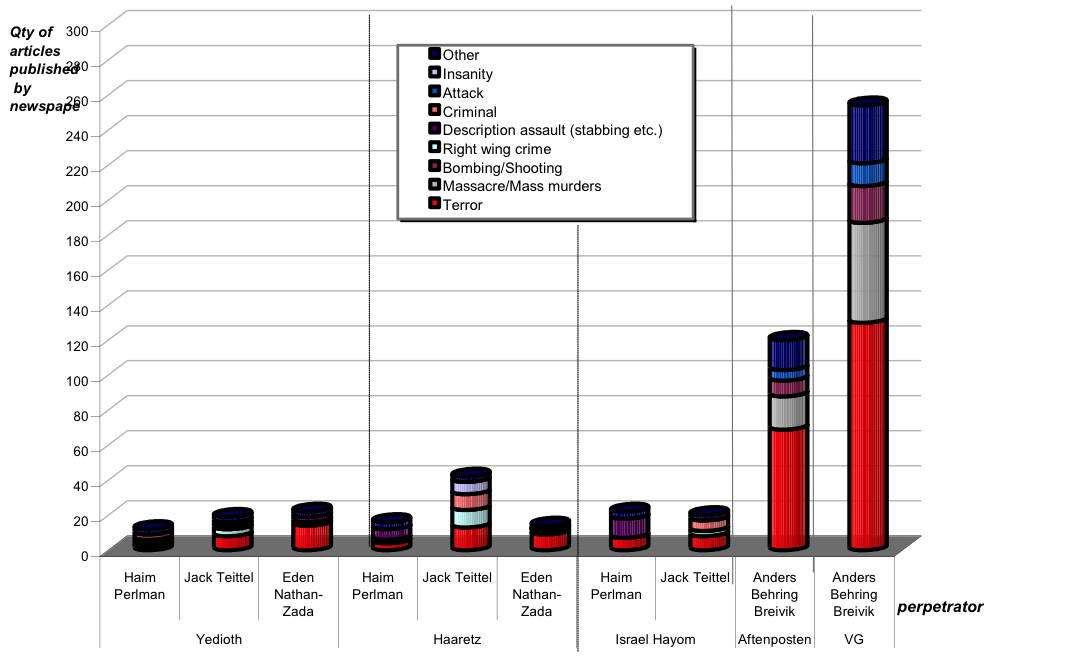

Addressing RQ2, Table 3 (see Appendix) summarizes the terminology used to describe the attacks. In a similar manner to the labeling of perpetrators as “terrorists” (Table 2), the most popular term to describe the acts in Israeli media was “terrorism”, a term that featured in 65 of the 167 (39%) references to the attacks. Again, the proportion of articles referring to the attacks as “terror” is greater in the cases of Nathan-Zada and Teittel, possibly due to the reasonable doubt concerning Perlman’s guilt. The second most common term to describe the attacks, far behind “terrorism”, is “right-wing crime” (N = 25), referring to the ideology of the attackers, and to the fact that they all spent times at illegal settlements before the attacks. The third group of terms (N = 23) contains various ‘technical’ descriptions of the attacks (assault, stabbing, etc.). Finally, the crimes are also labeled “criminal activity” (N = 20), although this term was used primarily to describe Teittel’s attacks (17 of a total of 20 references): In this case, Teittel’s sanity was questioned, as were his ideological motives. We found minor differences between the labels used to describe the crime in the Israeli newspapers.

Similarly, in Norway, “terrorism” was the term most commonly used to describe the attacks, appearing in 199 of 374 (53%) references to the attacks. The second most frequently used term was “mass murder/massacre”, which was used 76 times (20%). The first article about the attacks published by Aftenposten was entitled “Norwegian 32-Year-Old Behind Terror Attacks” (Aftenposten, July 23, 2011), which set the tone for all subsequent references to the attacks. VG started off in the same manner by publishing an article entitled, “When the Terror Came” (VG, July 23, 2011), stating that it was the first terror attack ever to take place in Norway. We found few differences between the labels used to describe the crime in Aftenpopsten and VG.

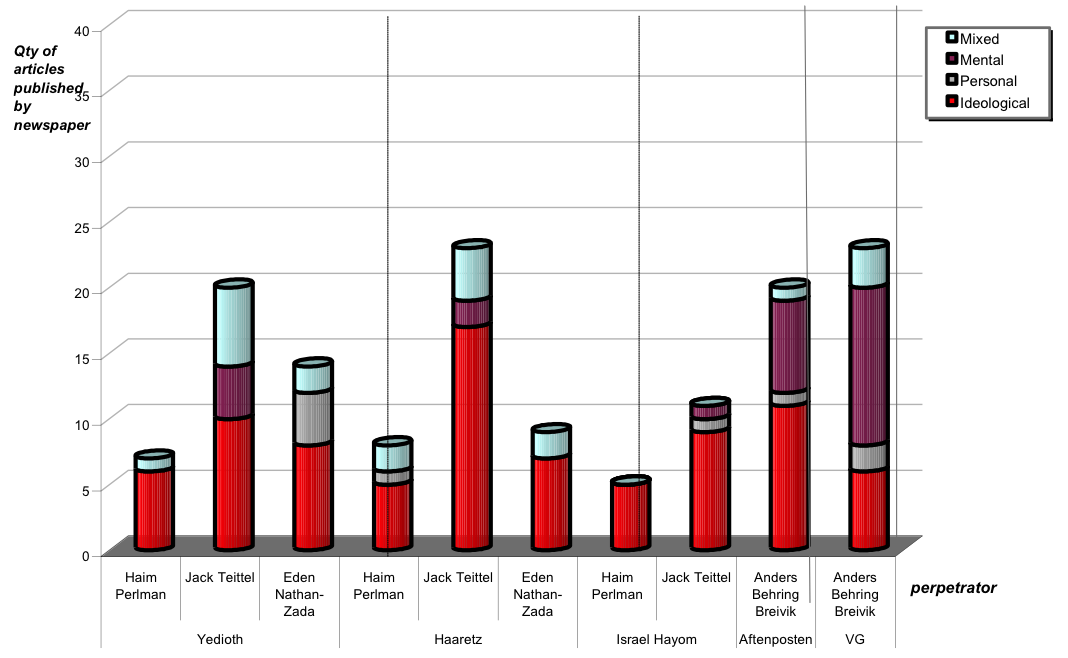

Addressing RQ3, Table 4 (see Appendix) summarises the papers’ descriptions of the motives underlying each attack. In the Israeli press, the motivation of all cases was primarily described as ideological: In 67 of the 97 (69%) references to the motivation behind the attacks, ideology was the sole motivation, and in additional 17 references ideology was one of several factors motivating the perpetrators to commit the attacks. This is surprising in view of the fact that in Teittel’s case, and to a lesser extent in Perlman’s case, there were serious concerns that personal and mental problems were involved. The debate regarding Teittel’s motivation is illustrated in Yedioth Ahronot editorials: Whereas an editorial on November 2, 2009, focused on Teittel’s mental condition and his belief that he was sent by God to commit his crimes and inspired by the 1977 action television series The Red Hand Gang, another editorial published on the same date by Nahum Barnea, one of Israel’s leading publicists, is entitled “Not Crazy” and explains that Teittel fits the term “terrorist” because of his allegedly clear “racist” ideology.

With regards to Anders Behring Breivik’s motives, sources are split between attributing his motive to ideology (17 of 43 references, or 39%) and to mental issues (19 of 43 references, or 44%). As Behring Breivik was completely unknown to the public prior to the attacks, most of the articles that addressed his motives were based on the anti-multiculturalist manifesto he had sent to several media and politicians shortly before the attacks, and on interviews with his former friends, his lawyer, and other experts. The manifesto was interpreted with similar frequency as proof that he was ideologically motivated or insane. VG, for example, pointed to several references in the manifesto that turned out to be untrue and lacking foundation in reality, and therefore concluded that Behring Breivik was delusional (“Living a Bluff.” VG, July 25, 2011). Both newspapers also elaborated on Behring Breivik’s abnormal social life, and VG explicitly states that Breivik was “a lonely man who killed to get noticed” (“Motive: Get Noticed.” VG, July 26, 2011). On the other hand, Aftenposten made specific references to right-wing extremists in the UK, including specific quotes such as “we are fighting a joint battle” (“Conjured Extreme Brits to Battle.” Aftenposten, July 27, 2011), alluding to Breivik’s ideological motivation.

Addressing RQ4, Table 5 (see Appendix) summarizes criticism directed to the authorities throughout the coverage of the attacks. Here, the analysis reveals that in all the three cases, the Israeli press harshly criticized the authorities for their failure to prevent the crimes (54 articles of the 134 articles, or 40%). In the case of Nathan-Zada, criticism is mainly directed towards the Israeli army and the Shin Bet (Israel’s internal security service) for failing to share information on the perpetrator, who apparently had openly expressed his desire to attack Arabs in order to stop the Gaza disengagement plan. Nathan-Zada deserted the Israeli army with his weapon for several months before his attack on Arabs, allegedly with minimum attempts from the military to capture him and relieve him of his firearm. On August 5, one day after the attack, Yedioth Ahronot’s headline reads “the Israeli Defense Force and the Shin Bet were Asleep”. That day’s editorial by Alex Fishman focused on how inadequate and “useless” the police, the army, and the Shin Bet were in failing to share information about Nathan-Zada. In the cases of Teittel and Perlman, criticism was also towards the Shin Bet, specifically its “Special Jewish Division” whose main goal is to curtail Jewish terrorism, for their failure to stop Perlman and Teittel and allow them to operate against Palestinians unrestrained for many years.

In contrast, criticism in the Norwegian newspapers regarding the terror attacks was for the most part absent during the 10 days of newspaper coverage examined in this study. Only five articles explicitly criticized the authorities for not being aware of Behring Breivik as a potential terrorist or for the time it took the police to reach the island. Several articles, including one entitled “Bombstreet was supposed to be Closed” (Aftenposten, July 23, 2011), contained some implied criticism of the failure to take security measures to prevent such crimes. Other articles mentioned how the Norwegian Police Security Service had never even heard of Behring Breivik although the Center Against Racism had been monitoring him for some time (“Was Unknown to PST.” VG, July 23, 2011), implying that Behring Breivik was someone that should have been watched. Most articles, however refer to the authorities’ response and many cite Director of the Norwegian Police Security Service Janne Kristiansen who said “Not even STASI [Ministry of State Security] could have stopped him” because he lived a “double life” and was for the most part a law-abiding citizen (“A Lonely Wolf that Could Not Have Been Detected.” Aftenposten, July 26, 2011). Articles that addressed the authorities’ response to the attacks praised the authorities and especially Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg for handling the matter and promoting a return to normalcy. Headlines labeled Stoltenberg “our new father of the fatherland” (VG, July 27, 2011), a label originally used to describe former Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen, who served 17 years in office and was credited with rebuilding Norway after WWII.

Discussion and conclusions

In light of several studies that found that US journalists persistently ‘repair’ the image of in-group perpetrators who commit crimes that fall within the US State Department’s definition of terrorism (Entman, 2004; Handley, 2008; 2009), we examined whether the practice extends to other democracies. We used Israel and Norway, two countries that saw in-group perpetrators committing violent attacks to achieve political goals, as our case studies. We found that the Israeli and Norwegian media typically labeled the attacks of as “terrorism”, the perpetrators as “terrorists”, and the motivation as ideological (rather than personal). Thus, the study clearly establishes that Israeli and Norwegian media shifted from a Jew/Christian (respectively) -as-terror-victim narrative to a Jew/Christian-as–terrorist narrative. This is in stark contrast to US media routines of ‘narrative repair’ applied to in-group perpetrators of crimes that fall within the US State department definition of ‘terrorism’. The study establishes that Israeli and Norwegian journalists challenged the conventional us/them dichotomist narratives and adhered to their professional norms of impartiality by labeling in-group perpetrators terrorists.

The differences between Israeli and US journalism practices are best illustrated in the case of Nathan-Zada, the US media portrayal of which was studied by Handley (2008). Handley noted that the US media did everything possible to ‘repair’ the conflicting image of a Jewish terrorist by focusing on Jewish concerns of Arab retaliation and by emphasizing that the crime was committed on Arab territory. In contrast, the Israeli media described the same perpetrator as a ‘blood-thirsty terrorist’ and in fact, throughout the Second Intifada, Israeli media aggressively sought to revise the long-standing narrative that Palestinians commit “terror attacks” while Jews “retaliate” (Philo & Berry, 2004; Dor, 2001). In the coverage of Nathan-Zada’s attack in the Israeli media, the “Jew as terrorist” narrative was dominant and alternative narratives were not suggested. For example, the Israeli media did not emphasize that after Nathan-Zada’s attack, the Arab masses on the bus lynched him to death although at that stage he was unarmed. The lynch was consistent with the Jewish street’s conception of Arabs as barbarians, particularly in light of the notorious October 2000 Palestinian lynching of Israeli soldiers in which, according to the Institute for National Security studies, “shocked” Jewish-Israeli viewers and emphasized the “otherness” of the Palestinians (Feldman, 2002). Overall, it can be argued that while US media representations strongly followed the rhetoric of an ‘us’/‘them’ dichotomy, Israeli media made no distinction between the coverage of Nathan-Zada and Palestinian perpetrators of similar crimes.

Both the Israeli and Norwegian press labeled the perpetrators “terrorists” and the attacks “terror”, yet the Israeli press assailed the authorities for their role in the attacks more aggressively than did the Norwegian press. In all the three cases examined, the Israeli media criticised the Israeli authorities for failing to prevent the attacks. Criticism specifically targeted the Shin Bet, despite the clandestine nature of this organization’s operations, reflecting Israeli media’s practice of challenging hegemonic discourse and institutions (Wolfsfeld, 1997; 2004). In contrast, the Norwegian media supported the administration’s argument that there was no way of preventing the crime.

Importantly, we found minor differences between the newspapers examined and their outputs regarding the attacks. Whereas it is normally difficult to find agreement on political issues in Israel between the right-wing oriented Israel Hayom, the left-wing Haaretz, and the mainstream Yedioth Ahronoth (Persiko, 2009), all three newspapers labeled the attacks and the perpetrators as “terror” and “terrorists”, respectively (although Israel Hayom was less inclined to label Perlman a “terrorist”). All three Israeli newspapers attributed ideological rather than personal motives to the perpetrators, and criticized the authorities for their “incompetence” in their failure to arrest the perpetrators in time. In Norway, although the language of VG (tabloid) is more graphic than Aftenposten (broadsheet), the representation of the perpetrator, the labels used for the attacks, and the description of the motivation behind the attacks are similar.

Based on the comparative politics literature (Hallin & Mancini, 2004; Schaefer & Wolfsfeld, 2009), we suggest that to understand the differences between Israeli and Norwegian versus the US practices in describing in-group attacks, we should consider the impact of the political system in those countries on journalists’ routines and norms. As early as the 1960s, Dahl (1966) hypothesised that extreme dissenters may enjoy more freedom to express their opposition in multi-party political systems characterised by a large number of parties and great ideological distance between the extremes, in comparison to high-consensus two-party systems (Sartori, 1976) such as the US. According to this argument, the media in multi-party system countries are less hesitant to challenge the dominant narratives than their two-party system counterparts because the former perceive that the public opinion is highly diverse (Benson & Hallin, 2007; Cook, 1994; Entman, 2004; Hallin & Mancini, 2004; Schaefer & Wolfsfeld, 2009).

Sheafer and Wolfsfeld’s (2009) comparative study on media coverage during four election campaigns in the US and Israel revealed that Israeli media offered far greater access to a variety of voices. Comparative studies of French media, operating under the multi-party system, and US media, offered similar results (Benson & Hallin, 2007; Cook 1994). These studies establish that the multi-party system not only promotes pluralism but also facilitates journalistic coverage that persistently challenges the dominant narratives produced by the administration (Scheafer & Wolfsfeld, 2009; Wolfsfeld, 1997). Accordingly, we suggest that it is the pluralistic and counter-hegemonic nature of the multi-party system that accounts for the journalistic shift from the ‘Jew-as-victim’ narrative to the ‘Jew-as-terrorist’ narrative in Israeli media, as well as the one-dimensional description of Breivik’s as a ‘terrorist’ in the Norwegian press. These practices stand in stark contrast to the ‘narrative repair’ of similar crimes (and in the case of Nathan-Zada the same crime) by the US press. Despite the fact that the image of the in-group perpetrators clearly challenged the ‘us/them’ dichotomy, Israeli and Norwegian journalists did not ‘repair’ the perpetrators’ image it to fit within conventional dichotomist narratives.

Comparative politics models also further heighten our sensitivity to minor differences between the Israeli and the Norwegian press, specifically the widespread criticism in the Israeli press against the authorities for their failure to prevent the crimes. Sartori (1976) argues that the probability of antagonism towards the authorities increases with the number of parties in multi-party systems. Thus, he distinguishes between moderate and polarized multi-party systems. According to Sartori (1976), moderate pluralist party systems (e.g., Germany and most of the Scandinavian countries including Norway), are characterised by few (typically less than five) political parties, with relatively small ideological distances between the extreme parties. In contrast, polarised multi-party systems (e.g., France, Israel, and Italy) are characterized by a large number of parties and marked ideological distance between the extremes. Our findings support Sartori’s (1976) contention, as we found that Israeli press, operating in a polarised multi-party system, was dramatically more aggressive than its Norwegian counterpart in criticising the authorities for their alleged role in the attacks.

To the best of our knowledge, literature on the representation of in-group crimes that come under the definition of ‘terrorism’ is still scarce. This pioneering attempt to address the topic using a comparative approach illuminates the differences between the practices and routines of US journalists and that of Israeli and Norwegian journalists. Future studies should expand the comparative analysis to other countries and party systems to continue mapping the portrayal of in-group attacks that fall within the definition of ‘terror’. In addition, studies should examine whether changes in state administration and policy affect media practices. For example, studies should examine whether the transition to the Obama administration, which subscribes to a harsher policy concerning Jewish settlements than the Bush Administration, affected the narrative used in the US media to describe Jewish settlers’ attacks against Palestinians. Finally, since the attacks examined here were all performed in the name of right-wing ideology, future studies should extend the analysis to left-wing motivated crimes to examine the extent to which political bias affects the media representation of the crimes.

Appendix

Table 1. Number of articles concerning each of the attacks

Table 2. Terminology – perpetrator

Table 3. Terminology used to describe the acts

Table 4. Motives attributed to the perpetrators

References

Altheide, D. L. (2006). Terrorism and the Politics of Fear. Cultural Studies <=> Critical Methodologies 6 (4): 415-439.

Altheide, D. L. (2009). The Columbine Shootings and the Discourse of Fear. American Behavioral Scientist 52: 1354-1370.

Atkin, D. J., &. Fife M (1993). The Role of Race and Gender as Determinants of Local TV News Coverage. Howard Journal of Communications, 5(1): 123-137.

Ayish, M.I. (2002). Political communication on Arab world television: Evolving patterns. In: Political Communication, 19 (2): April-June, pp. 137-154.

Benson, R. & Hallin, D. C. (2007). How States, Markets and Globalization Shape the News: The French and US National Press, 1965-97. European Journal of Communication 22 (1): 27-48.

Berelson, B. (1952). Content Analysis in Communication Research. New York: Free Press.

Berkowitz, D. (2005). Suicide Bombers as Women Warriors: Making News through Mythical Archetypes. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 82 (3): 607-622.

Bird, E. S., & Dardenne R. W. (1988). Myth, Chronicle and Story: Exploring the Narrative Qualities of News. In James W. Carey (Ed) Media, Myths, and Narratives: Television and the Press pp. 67-86. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Carey, J. W. (1992). Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society New York: Routledge.

Caspi, D. & Limor, Y. (1999). The In/Outsiders: The Media in Israel. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Chomsky, N. (1992). Deterring Democracy. New York: Hill and Wang.

Cook, T. E. (1994). Domesticating a Crisis: Washington Newsbeats and the Network News after the Iraq Invasion of Kuwait. In William Lance Bennett and David. L. Paletz(Eds). Taken by Storm: The Media, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy in the Gulf War pp.105-30. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dahl, R. A. (1966). (Ed). Epilogue to Political Opposition in Western Democracies, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

DeFoster, R. M. (2010). Domestic Terrorism on the Nightly News (Thesis). PhD. diss. University of Minnesota. Retrieved from http://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/93028/1/DeFoster_Ruth_May2010.pdf.

Dor, D. (2001). Newspapers under the Influence. Tel-Aviv: Babel (in Hebrew).

Entman, R. M. (1991). Framing US Coverage of International News: Contrasts in Narratives of the KAL and the Iran Air Incidents. Journal of Communication 41(4): 6-27.

Entman, R. M. (2004). Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Feldman, S. (2000). The October Violence: An Interim Assessment. Strategic Assessment 3 (3). Available from http://www.inss.org.il/publications.php?cat=21&incat=&read=647

Hallin, D. C. & Mancini P. (2004). Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Handley, R. L. (2008). Israeli Image Repair: Recasting the Deviant Actor to Retell the Story. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 32 (2): 140–154.

Handley, R. L. (2009). The Conflicting Israeli-Terrorist Image: Managing the Israeli–Palestinian Narrative in the New York Times and Washington Post. Journalism Practice, 3(3): 251-257.

Kampf, Z. & Liebes T. (2009). Black and White and Shades of Gray Palestinians in the Israeli Media During the 2nd Intifada. The International Journal of Press/Politics 14 (4): 434-453.

Korn, A. (2004). Reporting Palestinian Casualties in the Israeli Press: The Case of Haaretz and the Intifada. Journalism Studies 5 (2): 247-262.

Lule, J. (2001). Daily News, Eternal Stories: The Mythological Role of Journalism. New York: The Guilford Press.

Nacos, B. L. (2007). Mass-Mediated Terrorism: The Central Role of the Media in Terrorism and Counterterrorism. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Nacos, B. L., Bloch-Elkon Y., & Shapiro R. Y. (2011). Selling Fear: Counterterrorism, the Media, and Public Opinion (Chicago Studies in American Politics). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Neiger, M. & Zandberg E. (2004). Days of Awe: The Praxis of News Coverage during National Crisis. Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 29 (4): 429-446.

Pepper, A. (2010, December 31). The Number of Palestinian Suicide Attacks is the Lowest This Year Since 2000. Haaretz, Available from http://www.haaretz.co.il/news/politics/1.1238112.

Persiko, O. (2009, February 10). In Avigdor’s Backyard. Haayin Hashviit, (in Hebrew).

Philo, G., & Berry, M. (2004). Bad News from Israel. Ann Arbor, MA: Pluto Press.

Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. London: Cambridge University Press.

Scheafer, T, & Wolfsfeld G. (2009). Party Systems and Oppositional Voices in the News Media A Study of the Contest over Political Waves in the United States and Israel. The International Journal of Press/Politics 14 (2): 146-165.

Schudson, M. (1989). The Sociology of News Production. Media, Culture & Society 11: 263-82.

Slater, J. (2007). Muting the Alarm over the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The New York Times versus Haaretz, 2000–06. International Security 32 (2): 84-120.

Topo, G. (2006, June 5). Teenagers who Plot Violence being Charged as Terrorists. USA Today 7D.

Tuchman, G. (1973). Making News: Routinizing the Unexpected. The American Journal of Sociology 79 (1): 110-131.

Van Gorp, B. (2007). The Constructionist Approach to Framing: Bringing Culture Back In. Journal of Communication 57(1): 60-78.

Vidal, G. (2001). The Meaning of Timothy McVeigh Vanity Fair, September. Retrieved from http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2001/09/mcveigh200109

Wolfsfeld, G. (1997). Media and Political Conflict: News from the Middle East. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wolfsfeld, G. (2004). Media and the Path to Peace. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wolfsfeled, G., Frosh P. & Awabdy, M. T. (2008). Covering Death in Conflicts: Coverage of the Second Intifada on Israeli and Palestinian Television. Journal of Peace Research 45 (3): 401-417.

About the Authors:

Tal Samuel-Azran, The Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya.

E-mail Address: tazran@idc.ac.il

Amit Lavie-Dinur, The Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya.

E-mail Address: amitld@idc.ac.il

Yuval Karniel, The Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya.

E-mail Address:ykarniel@idc.ac.il