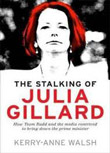

Walsh, Kerry-Anne - The Stalking of Julia Gillard: How the media and Team Rudd brought down the Prime Minister, Allen and Unwin, Crows Nest, 2013, (pp. 305) ISBN 9781742379227

Reviewed by Myra Gurney - University of Western Sydney (UWS), Australia

It’s official. Prime Minister Julia Gillard is a dud. The first female prime minister of Australia is a shocker. Lacking in character, incapable of governing, hopeless, and a liar to boot. We know this because dozens of political journalists in Canberra, plus ‘specialist’ political commentators who never turn up in parliament, radio shock jocks in capital cities who never grace parliament’s doors, and a grab-bag of internet amateur scribes and conspiracy-peddlers who could be anywhere, tell us so in their analysis of Gillard’s one-year anniversary as prime minister.

(13)

In the aftermath of the 2013 Federal election, the pivotal role of the media in framing the narrative of political players and government policies, is achingly obvious. Any pretense of objectivity, of critical analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of alternative policies or of the alternative leaders, has long been surrendered. The Murdoch press in particular hoisted its petard to the success of Tony Abbott from the moment the election was officially called with the tenor of news coverage slammed by former Labor prime minister Bob Hawke as “absolutely terrible bias” which he considered “unique” in his time in politics. The long predicted outcome of a return of the Liberal/National Party coalition to government can be seen as the denouement of a rabid media campaign which began not long after the Labor government ousted leader Kevin Rudd mid term and installed his deputy Julia Gillard as Australia’s first female prime minister.

As the dust settles and the recriminations begin about what went wrong for Labor, Kerry-Anne Walsh’s book (published before Rudd’s resurrection as prime minister in June 2013), provides an important case study of the period of Julia Gillard’s minority government, one of the most tumultuous in Australia’s recent political history. Walsh is a former Canberra press gallery journalist of 25 years experience and she makes no bones about her view that there has been a significant decline in the journalistic standards around the reporting of politics. Her language is scathing and her argument polemical. She presents her case by chronicling and dissecting (‘eviscerating’ is perhaps a better description) step by step, the media coverage of the Gillard government period between 2011-2013 and the role of former PM Kevin Rudd in that coverage. She says that while she initially intended to map the passage of Australia’s first minority government since 1939, she began to note that the biggest threat to Gillard’s government came not from Tony Abbott, but from within Gillard’s own party as Rudd and a band of disaffected supporters, leaking and backgrounding journalists, constantly threatened to derail its success. She observed that ‘as the months passed, the vast resources of the press gallery became more focused on Rudd’s ambitions for a comeback than anything the historic minority parliament had to offer’ (xi). While the threat to Gillard’s leadership from within were for most of her term more imagined than real, it became the primary prism through which political issues were reported, eventually becoming a self fulfilling prophesy. As Walsh notes early in the book that:

The raging against Gillard and the constant marking down of her performance is wildly at odds with the reality of the minority government. Despite the government’s wafer-thin margin, the parliament is remarkably stable; but it’s depicted as though we are living through the last days of Rome.

(41)

The paucity of political journalism in Australia has been critiqued before – Barrie Cassidy’s (2010) The Party Thieves and Lindsay Tanner’s (2011) Sideshow: Dumbing down democracy are two recent Australian examples – but the Gillard/Rudd tussle provides a perfect case study of this in action. If you believed the media framing, it was a battle of Shakespearean proportions, one which according to Walsh, was wildly at odds with the reality of the numbers on the ground. Gillard was constantly cast as the highly ambitious interloper who, Lady Macbeth-like, took up her knife at the behest of the ‘faceless men’ to usurp the prime ministership from the hapless Kevin. She was never able to caste off the stench of so-called ‘illegitimacy’ even though in the Westminster political system, parliamentary parties elect their leaders from the existing pool of elected representatives: and the party itself on three occasions between 2010 and 2013 soundly rejected Rudd.

Leadership tussles in Australian politics are of course nothing new – Howard and Peacock, Hawke and Hayden, Hawke and Keating, Howard and Costello, to name the most memorable. But this situation was unique – a first term prime minister had been removed in a dramatic late night coup, much to the dismay, horror and ultimate surprise of the Australian voting public and to the core of the Canberra press gallery. According to Special Minister of State, Gary Gray, central to the gallery’s subsequent obsession with Gillard’s leadership and Rudd’s unbridled determination to regain his old job, were the surprising events of June 23, 2010.

… all except a few ABC journalists were caught off guard … Now they are keeping watch … and jumping ‘at every single shadow they see’ … ‘Meanwhile, the actual processes of the [minority] government continue to work well …’

(170)

Walsh’s ‘expanded personal diary’ as she describes it (xii), lays out the minutiae and timeline of media coverage of the Gillard government between June 2011 (the ‘sackiversary’ as imaginatively labelled by The Daily Telegraph’s political blogger Tim Blair) and early 2013, and she pulls no punches with her damming critique or with her language as the pun-laden narrative shows. Her hypothesis, which she supports with a detailed tableau of daily examples, is that the mainstream media (newspapers in particular) became so obsessed by the never ending drama and possibility of a Rudd resurrection, that they essentially ‘lost their way’ to quote Gillard’s explanation for the party’s removal of Rudd. Rumours about leadership instability, fed mostly by Rudd and his loyalists, were given unqualified credence and reported as fact, creating an atmosphere of apparent constant chaos and diverting attention from the real, but much less dramatic news, of a productive and relatively well functioning minority government. The other beneficiary of this obsessive focus was Tony Abbott who was able to run an opposition attack and election campaign where his attacks and alternative policies, as much as they existed, were barely scrutinised. The overarching message of the 2013 campaign was ‘trust me, we HAVE to be able do it better than this lot’.

On this note Walsh is hugely critical of many of her press gallery colleagues and she writes in the book’s Preface:

While there are rigorous and highly competent journalists reporting from the press gallery, what confounded and disturbed me as the months passed was how many more got swept up in Rudd’s power play, giving undeserved momentum to his ambitions to reclaim the prime ministership. They became players, not reporters.

(xii)

The prominence and treatment given to the Rudd narrative nourished a kind of visceral groupthink. This fed into perceptions captured by the never-ending leadership polls, ultimately becoming a self-fulfilling prophesy. The abandonment of the long held principles of serious journalism of fact checking, objectivity and balance, not to mention the surrender of healthy scepticism of ‘trusted inside sources’, she argues was driven largely by the need to feed the 24 hour news cycle. However many succumbed to the vicarious thrill of being ‘trusted sources’ to the over-hyped drama being played out in Canberra. The impact was coverage predominantly driven by the vacuous agendas of public relations, marketing and personality politics. The result has been to feed an increased level of distrust and cynicism about politicians and the political process in particular as well as in the credibility of the mainstream media in general. This has serious implications for democracy.

The book highlights several underlying issues which are key to understanding this extraordinary time. They mostly remained, (and continue to remain), invisible and unexplained to the greater Australian voting public by virtue of both the collective blindness of much of the mainstream media, and the commercial imperative which drove its alternative agenda. These intersecting forces, the precarious nature of the minority parliament plus the personality, style and modus operandi of Rudd himself, created a kind of ‘perfect storm’.

It is on the subject of Rudd’s duplicity and role in the perception and ultimate fortunes of Gillard that Walsh is strongest and most strident. This is important as it sets the context for much of what came afterwards. At the outset, she quotes a trusted but anonymous ‘former high level policy advisor’ who, in a personal and an unpublished account of his time in the Rudd government, wrote that:

‘[t]he Rudd government was never and could never have been a functional government because of the man who ran it’.

(2)

The dumping of Rudd and his replacement with his deputy in June 2010, was not merely spurned from oft reported party panic over poor opinion polls after Rudd had forsaken the emissions trading scheme or because of the unbridled ambition of Julia Gillard. The same advisor grouped the flaws of the Rudd governing style into a number of categories:

(1) the radical centralization of decision-making to Rudd himself even though he wouldn’t or couldn’t make decisions; (2) Rudd’s chairing of a terrible cabinet process that ignored or wasted the skills of his ministers and officials; (3) Rudd trying to do too many things; and (4) trying to do them too quickly; (5) his neglect of policy in favour of an overwhelming focus on political and media considerations; and (6) a culture of blame and retribution he personally nurtured that stifled honest advice and undermined decision-making.

(197)

It was also partly due to a long standing ‘deep seated unease’ within his own party about Rudd personally:

… his over-whelming personal ambition, his ruthless use of people and power blocs to get the leader’s job, his lack of strong policy focus and his uneven temperament.

(3)

This character assessment has been backed up by others, most presciently by former ALP leader Mark Latham in The Latham Diaries (2006), written before Rudd became ALP leader, and more recently by former speechwriter James Button (2012) in Speechless: A year in my father’s business who, in more measured tones, described Rudd as both ‘obsessed with order and a peddler of chaos’ (65). It was this chaotic work style, his apparent narcissism, arrogance and disregard for his colleagues, plus his apparently insatiable desire for popular approval and media attention, something which he had used to such good effect in 2007, that were the major contributors to his government’s difficulties in realising many of its policy objectives. According to one Labor source cited, ‘Kevin is the Kim Kardashian of politics’ (263).

The fact that this was not reported Walsh argues, contributed to the later ability of Rudd and his supporters to ‘maintain the rage’ and to feed the ongoing sense of crisis, ably perpetuated by the media.

There seemed to be a lack of appetite for rigorous assessment of Rudd the man and Rudd the politician, and of his motives and the devastating impact he was having on the government. … The underhanded work being done by his acolytes was respectfully kept in the shadows while being given headline treatment.

(xii)

It was this complicity, that she finds most ethically deplorable among her press gallery colleagues.

Once deposed, Rudd’s toxic ambition appears to have either to return to the leadership, or to destroy both the government that had dumped him and the woman who replaced him. In this pursuit, he was abetted by political journalists who became his pawns in his comeback play, channelling the Chinese whispers of his spruikers and giving credibility and substance to exaggerated claims about the pretender’s level of support within the parliamentary party for a comeback.

(2)

While the charge of actively trying to destroy the government may be a bridge too far, others have opined that Rudd’s relentless pursuit of Gillard is testimony to his inherent sense of superiority and entitlement, his narcissistic belief that only he could be Labor’s savior as well as his refusal to acknowledge or accept any responsibility for his own part in his government’s woes. On June 10, 2013 during the ABC’s Q & A program, Mark Latham went further, saying that:

He knows that every day that he gets in the media cycle he’s knocking Gillard down a notch or two in the polls. This is a program, a jihad of revenge the like of which we’ve never seen before in the history of Australian politics, and it goes beyond the normal human reaction of revenge.

In support of this, Erik Jensen in a May 2013 article for The Monthly labelled Rudd ‘the saboteur’. After Rudd was returned to the leadership, David Marr (2013) revisited the theme of his Quarterly Essay with this assessment:

His self-belief is bottomless. There were dark nights for Rudd after his defenestration but it remained a constant comfort that he had never been rejected by the Australian people.

And in the aftermath of the Labor election loss, several ex-ministers have directly and indirectly hit out at Rudd’s role in the party destabilisation: former trade minister Craig Emerson’s recent critique being the most scathing. Rudd may have been returned reluctantly to ‘save the furniture’, but the irony is that if Walsh’s account is accurate, Rudd was the arsonist in the first place.

The second major theme running through the book is the manner in which so much of the focus of reporting during this time was through the leadership tension prism. Despite numerous strong policy initiatives – the NDIS, the price on carbon, maintenance of a strong economy despite a global crisis, historically low interest rates, healthcare reforms to name a few – insufficient attention was given to these important stories or they were editorialised as being bad or incompetent. In the case of the health care reforms in February 2013, Walsh writes that:

Buried in eight paragraphs on page two of the same paper [which falsely reported Gillard’s use of internal polling to usurp Rudd], is a story about the private health care package passing the House of Representatives. It is a $3 billion quintessential Labor reform … It’s a big story with a big reader impact, particularly for the Sydney Morning Herald’s middle class readership. But it is considered of secondary consequence when lined up against stories about leadership challenges that haven’t been launched.

(2)

Every policy setback such as the High Court’s rejection of the ‘Malaysia Solution’ or political controversy such as that which embroiled Craig Thomson or Speaker of the House Peter Slipper, is framed in terms of leadership instability and unfavorable opinion polls.

A picture of [Gillard] losing her grip on power and authority is presented daily to voters and media consumers, despite no evidence being provided to back up that conclusion. The government is suffering policy difficulties, as any government will from time to time, and there is a clutch of MPs who want Rudd returned; but they’re a minority desperately trying to entice the media to blow strong wind into their sails.

(2)

Walsh is not uncritical of Gillard whom she judges as not always being her own best advocate. Her wooden public performances such as the ‘moving forward’ election speech and her switch to the ‘real Julia’ during the 2010 election, her ill-advised support for Craig Thomson and her co-opting of the terminally tarnished Peter Slipper from the Coalition to be Speaker of the House in order to bolster numbers, were not the decisions of someone known for her political pragmatism and common sense. Walsh questions the role and influence of the media managers and advisors in Gillard’s poor public persona although this is not a major focus. She ponders:

I wonder about the vacuousness of contemporary politics, in which an effervescent, smart woman has been forced to undergo public transformation into a starched and over-scripted public figure.

(117)

The role of Gillard’s gender is also a relevant perspective. The focus of much of the coverage on her looks, her dress, her love life, her marital status, her childlessness, her atheism was also used to subversively frame her as alternatively weak, hysterical, a ‘ball breaker’ and out of touch with ‘real women’. The vitriol and sheer malevolence of the ‘cranky old blokes in Sydney and Melbourne radio’ (45) such as Alan Jones, Neil Mitchell, Ray Hadley and Chris Smith, not to mention hyperventilating conservative columnists such as Andrew Bolt and Piers Ackerman, was beyond measure. From the constant use of Gillard’s first name (‘would a headline writer have used just the christian names of John Howard or Peter Costello?’ (57)), Alan Jones’s description of Gillard as ‘Juliar’, through the ‘Ditch the Witch’ banner at the anti-carbon tax rally and so on, the tenor of the coverage licensed parts of the media as well as the Opposition, to indulge in unprecedented levels of personal abuse and disrespectful commentary. This became the dominant discourse and would have acted to further erode public respect for the person and the office, a point made in incisive fashion by journalist and feminist activist Anne Summers (2012) in a speech titled ‘Her rights at work: The political persecution of Australia’s first female prime minister’ .

On this point Walsh remarks:

One wonders if their bile and venom would be directed at a man; the disrespect they show Gillard and the office of prime minister is unprecedented.

(35)

The ensuing disconnect between mainstream and social media reaction to Gillard’s ‘misogyny speech’, which went viral around the world, Walsh cites as evidence of the extent to which the press gallery was so caught up in the anti-Gillard frame as to have lost their broader critical capacity.

The third major theme is the barely hidden collusion that she notes between those she disparaging calls ‘Team Rudd’ and many in the press gallery. The point she makes again and again is that this is a strategy of what she calls ‘fake it until you make it’ (176) or what The Punch’s David Penbethy labels ‘dump and deny’, adding that ‘we in the media should reflect on our complicity in this kind of journalism’ (205). It is a question of journalistic integrity and Michael Gawenda, respected former editor of Melbourne’s The Age newspaper was unequivocal when he wrote after Rudd’s resignation from the position of Foreign Minister and retirement to the backbench in February 2012:

Those playing the game of protecting anonymous sources and promoting their falsehoods are lying, and retelling the lies of Rudd and his mob … At his two bizarre press announcements in Washington, Kevin Rudd spoke as if he was a total innocent, as pure as the driven snow, morally virginal, having never ever been involved in the grubby politics of undermining, white-anting, wounding and ultimately destroying an opponent.

(193)

His conclusion takes aim at the ethics of his beloved profession:

The rules of engagement in Canberra no longer serve the public interest: ‘They encourage and support dishonesty from politicians and, yes, dishonesty from reporters and commentators’.

(194)

Following on from this, the final overarching theme, though not overtly articulated by Walsh’s analysis, is the extent to which the line between reporting, opinion and analysis has become blurred, something which has been accompanied by the trend to ‘brand’ both serious journalists and other political commentators with a kind of pseudo-celebrity status. All traditional print and online news organisations have their resident sage whose profile is central to the their brand and their credibility. Retired former politicians such as John Hewson, Mark Latham and Graham Richardson sit seer-like on TV news programs offering words of wisdom and insider perspectives like commentators at a football match. Walsh gives multiple examples of tea leaf-like reading of the impending demise of Gillard’s leadership, despite any concrete evidence to support what was no more than wishful thinking and she argues that these are:

… assumptions and judgements based on nothing more than the handkerchief-over-the-mouth-piece titterings of Rudd’s people.

(83)

These observations are examples of what Blumler and Kavanagh (1999) famously labelled the ‘third age of political communication’ that has recast the role of the political journalist from observer and commentator into agent-provocateur or actor in the process. While generally the book does not attempt any substantial in-depth analysis of this phenomenon, Walsh occasionally speculates:

Or do journalists know this [that Gillard still has 75 percent support] but is their ‘reporting’ is propelled by a need to keep the bosses happy by dishing up sensationalist stories in a competitive market? The Rudd challenge is a make-believe that wants to be taken seriously.

(83)

This is a shortcoming although perhaps not primary rationale for the book. In making a similar point, Lindsay Tanner (2011) for example noted that:

It is interesting that working journalists now use the slang term ‘yarn’ to denote a story.… In a typical yarn, the need for entertaining an diverting content takes precedence over the need for factual accuracy: the story is meant to entertain, not to inform.

(33)

The extent to which this situation is also a product of the lack of media diversity in this country and of the general problems resulting from the political economy of media, is not explored, although again this was not the key rationale for the book. While she criticises prominent journalists such as The Sydney Morning Herald’s Peter Hartcher extremely harshly for their complicity, she does not expand her critique to question the role or motivations of the editorial team behind the stories. Why were there so many weakly argued, illogical stories, why so many variations of the same theme, why so much ‘he said, she said’ journalism feeding the loop? The problems are systemic rather than merely individual.

Repeated attempts were made by the Gillard camp to fight back: the belated damming public critiques of Rudd’s administration by respected and prominent ministers such as Tony Burke, Wayne Swan and Nicola Roxon, were unprecedented attempts to tell the real story (too late). The twice called leadership spill by Gillard, one of which resulted a day of high farce and in the mass resignation of Rudd loyalists and of former leader Simon Crean whose attempt to ‘take one for the team’ was foiled when once again Rudd refused to challenge due to lack of numbers. All of this very public squabbling was grist to the mill of the Opposition and understandably fed the general public perception of instability and incompetence of a grossly divided government. It also neatly distracted the media from any critique of the Abbott’s ‘stop the boats’ and ‘end the carbon tax’ mantra or of the constant narrative of a budget emergency and an economy in crisis, despite major economic indicators and a raft of trusted economists decrying this interpretation.

While for political junkies the minutiae of party politics may be endlessly fascinating, did it really matter in the end? Or are there more complex forces at work? During the election campaign, respected economics journalist Ross Gittins wrote in a piece titled ‘Why election campaigns have become so vacuous’ that:

It’s not their [campaign advisors] job to foster debate, or ensure voters are fully informed on the choices available to them. And being open and accountable is more likely to lose you votes than win them. … If it’s just about attracting enough votes to win, and that’s not easy, better not to waste time on anything that doesn’t do much to help. Why waste your energy trying to win the votes of people who long ago decided not to vote for you or those who are always going to vote for you?

Supporting this, in a review of the 2013 campaign, Greg Jericho wrote similarly arguing however that in comparison with 2010, there was much better coverage of policy details if you knew where to look. However:

… did a majority of voters see this plethora of detail? I would argue much fewer did than ever before. … This divide of the information-rich and information-poor voters is now so great that there is little reason for parties to bother with policy details. Details barely get reported on the 6pm news bulletin in the midst of another ‘exclusive poll’, nor are they found on the front pages of the tabloids.

He concludes:

I think that is a situation both major parties will be only too happy to exploit. I expect we’ll be fed more policies with more vague details that are revealed fully only after the election. And I can’t see how that is good for voters.

Although outside the timeframe of the book, we now know how it all ended for Julia Gillard and for the Labor Party. For readers whose political views fall on the progressive side of the spectrum, Walsh’s account is engrossing, if rather depressing, reading despite the oft-times provocative and punchy language. Those whose views fall on the conservative side may well say that Gillard got her ‘just desserts’, that she who lives by the sword, dies by the sword and that the Labor Party is its own worst enemy … and there may be some truth in that position. However for those idealists who still believe that the Fourth Estate has an essential function in the prosecution of genuine democracy and who believe in politics as a contest of ideas rather than personality and marketing, this case study is a somber and cautionary tale for our times.

About the reviewer

Myra Gurney is a Lecturer in communication and professional writing in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts at the University of Western Sydney. She is currently working on a PhD related to the political language and discourse of the climate change debate in Australia.