Volume 7 Issue 1 - 2013 Special Issue: Communication Technology and Social Life: Collaboration, Innovation, Conflict and Disorder

Editorial

Hart Cohen

University of Western Sydney (UWS), Australia

Welcome to the 2013 Volume of Global Media Journal/ Australian Edition. This is our seventh year of publication – a significant achievement in that the work required to publish the journal is largely voluntary. With ever increasing workloads, it is harder for academics to find the time to support ventures of this kind.

This issue marks the addition of Dr. Tanya Notley to the editorial team, who with Jonathan Marshall and Juan Salazar, co-edited the articles that form the themed section. The theme marries new media technologies and the varied ways they have manifested in human behaviours and social interactions. This is a rich and contemporary vein of media research.

Thanks to the editorial team, the reviewers for this issue, and to our usual team who have worked to realise this issue. We also launch a new look for our website with this issue. Thanks to Roman Goik and Lauren Oaklands for designing and developing this new iteration of Global Media Journal/Australia Edition.

Guest Editorial

Tanya Notley

University of Western Sydney (UWS), Australia

Jonathan Marshall

University of Technology Sydney (UTS), Australia

Juan Francisco Salazar

University of Western Sydney (UWS), Australia

This special issue of Global Media Journal – Australian Edition arose from a well-subscribed session at the Australian Anthropological Society Conference in 2012. Our explicit purpose in organising that panel – and this special issue – was to invite scholars to think about and discuss the material communicative basis of social interactions and the ways these shape and are shaped by an always-changing, ever-expanding range of technologies. Firstly, we were particularly interested in asking questions about the social organisations that form ‘around’ communication technologies, allowing innovation and making new openings. Secondly we wanted to provide a space for discussions around how technologies and social formations interact with, and possibly disrupt, more established social formations and organisations. Our aim was to open up new possibilities for exploring the ongoing – and social – nature of technological conflict, collaboration, disturbance and innovation.

The seven essays selected for this issue, which include a promising number from early career researchers, highlight the diversity of approaches that can be taken to study and analyse the material dynamics of communication technologies, and the further diversity of ways that communication technologies are embedded within social practices and activities. The papers are interdisciplinary and geographically varied. The areas they explore, include: a space that enables collaborative music production among friends and strangers; software that supports activists to talk and move content across languages; the use of social media to simultaneously contest and confirm Indigeneity; the many contradictions that emerge around discourses that promote and reject video-conferencing as a tool to work collaboratively and remotely; the role and experience of ‘perceived interconnectedness’ for entrepreneurial lifestyle blogging; the way that the very structure of the internet creates a perpetual ‘mess’ of information; and the ways that changes in the structure of a computer game can produce moral and ethical conflict. As they explore these diverse topics, the papers present a range of theoretical and methodological perspectives about how technologies ought to be investigated, not simply and purely as technical attempts to solve problems or produce efficiency, with linear and straightforward effects, but as creative social formations rife with complex and unintended consequences.

Most of the papers deal directly, or indirectly, with the effects of the material basis of communication technology on the structure, patterns, or organisation of communication, and give new importance to those patterns. Structures of communication enable or restrict: patterns of observation, regimes of privacy, turn taking in conversation, the range of people one perceives and hears, the kind of symbols in use, and so on. These social organisations and structures simultaneously include and exclude, make new openings while closing others, and create new needs while addressing older ones. They can foster ambiguity, generate new problems as well as new solutions, and open up fields previously unthought-of, which can then prove difficult to deal with. Power relations can be both unhinged and reasserted. Hence new structures of communication allow and encourage innovation and potential conflict. Changing structures of communication may be as important in their effects as changing economic or kinship structures.

Information and communication technology may simultaneously enable and restrict different interests and actions, so that the technologies are flexibly interpreted, shaped, fought over and negotiated. These processes can, again, lead to unpredicted, unintended, and unexpected consequences and impacts. As a result of these unintended consequences, the effects of a technology are not simply positive or negative, and different groups may have different experiences of the technology and its effects. This semi-contingent social-technical melding creates complexity, mess, friction and ambiguity, together with moral and ethical problems, all of which people struggle to sort out.

The contributions included in this special issue, in one way or another, all highlight the diversity of interpretations and uses of communication technologies; in so doing they reveal new insights into the material dynamics and processes of social lives and social activities that are mediated by technology.

The issue opens with Crystal Abidin and her ethnographic examination of Singapore’s commercial lifestyle blog industry. She compares what she calls ‘perceived interconnectedness’ with the idea of ‘parasocial relations’, pointing out that the former is an intensification and modification of the latter, arising through the potentials of new material structures of communication. Abidin writes: “While parasocial relations is unidirectional, hierarchical, and broadcast, ‘perceived interconnectedness’ is bidirectional, flat, and interactive … [It] is enacted by readers who envision a one-to-one mode of interaction with bloggers”. Her work investigates online everyday life by examining how some young Singaporean women are creatively leveraging blogs and other social media applications to earn money or even a living. In doing so, she discusses the familiarity and closeness readers’ feel toward these commercial bloggers while also considering how this ‘perceived interconnectedness’ may disrupt and disorder the personal lives of those bloggers. Abidin details some coping mechanisms, used by the bloggers, but we can see how changes in technology and the way it is exploited, leads to ambivalent or disordering results. There is no clear resolution, and that lack of clarity is a vital part of the dynamics of this online/offline life and its tensions.

In the next contribution, Rebekah Cupitt explores the conflicts between narratives, ideas and practices associated with video conferencing within a Swedish telecommunications company. Cupitt’s paper explores the ‘phantasms’ (or the shared, flowing and changeable imaginings or perceptions of an artefact, a social phenomenon or an event), which are embedded within varying socio-cultural contexts. Phantasms can change with contexts, the social group involved and their particular purposes. The idea is used to explore the “conflicting logics and active reasoning between multiple and sometimes discordant social meanings, diverse situations and multiple agendas”. The difficulties with socio-technical phantasms are explored in three different, but interconnected, contexts: first, in the discourse created by the company “aimed at prospective customers and the general public”; second in the discourse embedded in the company’s policy documentation, which is aimed at employees; and third, in the discourse of company employees, as they go about their work and negotiate the forms of communication that video conferencing simultaneously enables and restricts. While Cupitt finds that both policy and advertisements work to circumnavigate ‘the incompatibilities between numerous phantasms’, company employees still find it difficult to resolve these conflicts in their own discourse, work needs and lives.

In her paper on Kompoz.com, an online music collaboration service, Elaine Lally examines the opening up of new possibilities for global collaboration. The structure of Kompoz allows configurations of people to form around music objects and musical aspirations, but this does not mean that all collaborations are possible or desired. Norms and behaviours around group membership and participation are constantly being negotiated in ways that can appear awkward or ad-hoc. The music itself becomes an improvable, or alterable, object, with possibly strained collaborative ownership. As people upload their contribution to a track – whether vocals, a guitar riff, a drum layer, a remix version – they will often attach dialogue to their contribution. Lally finds that this attached dialogue provides evidence of “sensation, emotion, and pleasure for the participants”, although this may become conventionalised, as it is important to avoid offence and encourage others if people want to remain participants on a project or series of projects. Lally demonstrates that studying practice on sites like Kompoz can “deepen our understanding of communicative structures necessary to support creativity, and collaborative innovation, in distributed networks”.

Next, Theresa Petray looks into the way “social media offer the potential to creatively rethink and amend social practices.” Specifically, Petray focuses her analysis on the use of social media by Aboriginal activists in Australia to contest categories of Indigeneity. Even though self-writing can be perceived as individualistic and fragmented, Petray finds it can act as a “technology of the self” which can be harnessed for collectively-posed identity-building. This sets up a minor paradox, as it may in some fields, be useful to produce a “strategic essentialism” which communicates commonality within a group in such a way that it can set a group apart as special and unique. Yet a strategy of “strategic essentialism” can also set up irreconcilable difference, increase tensions, and be unfaithful to the ways that people actually live and perceive themselves. In discussing this issue, Petray focuses on a number of Australian Aboriginal activists who make use of the structures of communication provided by Twitter and Facebook to reflect on the complexity of their own Aboriginal identity and to connect with others (Aboriginal or not) in ways that allow for experiences to be shared. These processes of writing and communication enable self-categorisation to oppose the forcible categorising made by others, with all the power and displacement issues that this carries. Self-definition becomes “an act of activism and citizenship, driven by a range of motivations”. The process of self-identification is of course complicated, and Petray gives us some idea of its ambiguities and (real and potential) benefits.

In her examination of Entropia Universe, Rhian Morgan uses ethnography to delve into the depths of an online game and virtual world. While investigating the ways in which ethical claims and moral choices are tied into the material structures, or game mechanics, of the massive multiplayer online roleplaying game, Entropia Universe, Morgan maintains a focus on the way these game structures affect social life. “Updates to a game’s programming can result in alterations to the experienced ‘materiality’ of the game-world and, subsequently, necessitate cultural or ideological shifts”. Previously formed orders of understanding can be disrupted by software changes. The structural changes that Morgan describes, disorder previous ideas of moral order, causing ongoing debates that might never result in agreement or harmony. Morgan’s observations highlight that virtual worlds are social worlds and reveal how trust and ethics can develop and change in those worlds as the structures of action change, particularly with the added ambiguities of relative anonymity, and the possibility of players earning or losing ‘real world’ money. The analysis provides new understandings of the subtle ways virtual world producers might minimise, or engage with, the degree of disruption that code updates may and can cause to a social reality. The technology is not isolated from that reality, the social forms developed around it, or the pressures of profit.

Following on from here, Tanya Notley, Juan Salazar and Alexandra Crosby examine online video translation and subtitling in order to consider the implications of these emerging practices for social movements and activism in South East Asia. Their work sheds light into the ways that the combination of the internet, open source subtitling/translation software, and an open video activism sharing platform, allow collective translation groups to form and function in ways that enact the political sensibilities of the translators. The authors argue that this matters since, despite of the ubiquity of the internet internationally, language still acts as a barrier in addressing social and environmental justice issues. Notley, Salazar and Crosby claim that by addressing this and other barriers to social and political participation, online video subtitling and translation practices have the potential to become an important form of ‘citizens’ media’. The authors conclude that citizen translators believe “that by subtitling/translating videos in new languages they are helping to address social and political issues by allowing more people to become aware of issues and different (and more authentic) perspectives and by opening up who can become part of public dialogue.” The new communication structures created by the online video translation/subtitling software they examine, offers a new (albeit perhaps precarious and messy) opportunity for a new kind of multi-lingual global dialogue.

Finally, Jonathan Paul Marshall examines the way in which the internet as a structure of communication, enables and supports the easy production, storage and distribution (and thus the ‘free flow’) of information – especially as organised in ‘information capitalism’. These technological solutions to problems of information generation and storage, produce problems. Without disputing that information society has its good points, rather than simply celebrating this increased access to information and the increased production of information, Marshall claims that this fast, free flow of information produces problems, starting with information overload or ‘data smog’. Data smog, especially when welded to information as status or a profit marker, creates the beginning point for information mess, and in this mess almost any informational position or claim can be made or found. Using a number of vignettes, the paper explores how ten ‘information mess principles’ play out, showing their real, potential and future impact for our so-called information society. What Marshall calls information-groups (imagined communities grouped around types of information and sources of information, and placed in opposition to other information groups), and the presence of doubt become critical filters for individuals and groups to help deal with information overload and informational uncertainty; however the impacts of these filters are ambiguous. In Marshall’s dystopic caricature, part reality and part imagined reality, no one knows, or can know, what is happening.

This collection of papers explores the relationships between the structures of communication and the social lives that grow around those structures that may lead to the modification of those structures as people are included or excluded from using them, or find them insufficient, argue over whether they fail or succeed, or are awarded more capacity to implement new orders or control over them. In reviewing these papers and synthesising their findings, what we have discovered is that by acknowledging and analysing different and unique communicative ecologies and by refusing to ignore the sometimes confusing and conflicting co-existence of order and disorder, ambiguity and complexity, enablement and restriction, innovation and conservation, these papers make it apparent that communication technology can enable the creation of new social processes, but also that they can conflict with, disrupt, or exaggerate, existing ones. Without a focus on both old and new social practices as well as on unexpected or unintended impacts, writers of social theory can leave us with generalisations that evoke false or misleading pictures of smooth and stable social and technological developments. This may result in a premature optimism or pessimism that forecloses social and political possibilities, as well as social understanding. Ultimately, in providing a space for these articles to consider the broader communicative ecologies in which technologies are being used in social lives, our aim was to open up new possibilities for exploring the perpetual, innovative and social nature of technological adoption and adaptation. We hope that you too find that these papers challenge your ideas and evoke new ones, and that they contribute to the way we understand how communication technologies have, do, and might challenge, sustain and alter our social lives.

Special Issue Refereed Articles

-

Cyber-BFFs*: Assessing women's ‘perceived interconnectedness’ in Singapore's commercial lifestyle blog industry *Best Friends Forever

Crystal Abidin

Read Abstract Read Article

University of Western Australia (UWA), Australia

Phantasms collide: Navigating video-mediated communication in the Swedish workplace

Rebekah Cupitt

Read Abstract Read Article

The Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Sweden

Creative interactions and improvable digital objects in cloud-based musical collaboration

Elaine Lally

Read Abstract Read Article

University of Technology (UTS), Australia

Self-writing a movement and contesting indigeneity: Being an Aboriginal activist on social media

Theresa Lynn Petray

Read Abstract Read Article

James Cook University (JCU), Australia

Death in Space and the Piracy Debate: Negotiating ethics and ontology in Entropia Universe

Rhian Morgan

Read Abstract Read Article

James Cook University (JCU), Australia

Online video translation and subtitling: examining emerging practices and their implications for media activism in South East Asia

Tanya Notley

Read Abstract Read Article

University of Western Sydney (UWS), Australia

Juan Francisco Salazar

University of Western Sydney (UWS), Australia

Alexandra Crosby

University of Technology (UTS), Australia

The Mess of Information and the Order of Doubt

Jonathan Paul Marshall

Read Abstract Read Article

University of Technology Sydney (UTS), Australia

Postgraduate Submissions

-

Narrative, Commercial Media and Atenco: Mexican Television Corporations and Political Power

Socorro Cancino Cifuentes

Read Abstract Read Article

University of Western Sydney (UWS), Australia

Book Reviews

-

Digital Media and Reporting Conflict, Blogging and the BBC’s coverage of War and Terrorism

Kevin Childs

Read Review

RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

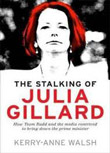

The Stalking of Julia Gillard: How the media and Team Rudd brought down the Prime Minister

Myra Gurney

Read Review

University of Western Sydney (UWS), Australia

Networks of outrage and hope. Social movements in the internet age

Ekaterina Tokareva

Read Review

RMIT University, Australia

Advertising, the media and globalization: A world in motion

Julie Bilby

Read Review

RMIT University, Australia

Journalism and Conflict in Indonesia: From Reporting Violence to Promoting Peace

Alexandra Wake

Read Review

RMIT University, Australia