Creative interactions and improvable digital objects in cloud-based musical collaboration

Elaine Lally

University of Technology (UTS), Australia

Abstract

This paper explores the activities and experiences of musicians using online platforms for collaborative creation. Music-making has always been a collaborative endeavour, and has always evolved to accommodate technological innovations. Consumer-level recording equipment has now made ‘home studio’ recording at near professional quality levels more accessible than ever before. Combining with new social media platforms, these domestic capabilities have created new possibilities for musicians to collaborate across the globe. Cloud-based platforms mean that collaborators no longer need to be present in the same place at the same time, but these platforms produce new challenges and constraints. This paper explores the infrastructure and community of one specialised cloud-based musical collaboration platform, Kompoz.com. It shows how this site catalyses the creative collaboration of those involved by providing a space for interaction between musicians and temporary ‘work-in-progress’ digital objects. Commentary on the audio tracks making up a project acts as ‘attached dialogue’, which facilitates the cumulative reworking of them as ‘improvable objects’. It is suggested that despite the inevitable limitations of online collaboration, asynchronous communication has advantages in providing time to reflect and evaluate.

Introduction

Music-making, collaboration and distribution have been transformed by technological developments many times throughout history. Prior to the invention of recording technologies in the late 19th century, music could only be experienced as live performance (either as audience or performer), and music-making at home was a near-universal pursuit (Cherry, 1984). The course of the 20th century saw music recording, production and distribution become global big business, intricately entwined with the development of radio, television and the cinema. The mass media dominated domestic leisure and entertainment through the latter half of the 20th century, with an increasing separation between those who actively performed music and those whose role was passive reception. Music-making for education, pleasure and performance may have remained a popular pursuit among young people, but for the majority it became either a solitary pursuit or a receding memory (Green, 2002; O’Shea, 2012).

In the 21st century, the lowering cost of high quality digital recording equipment and software, suitable for use by consumers working in home studios (Katz, 2010), has sparked something of a desktop publishing revolution analogous to that launched by the advent of laser printing and WYSIWYG formatting in the mid-1980s. These digital recording possibilities have combined with the online social media transition referred to as ‘Web 2.0’ to create a burgeoning and diverse ecology of online services and virtual communities. As a result, music-making is once more and increasingly becoming a democratised and participatory activity (Bloustien, Luckman & Peters, 2008).

Social media, such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, provide spaces where people find like-minded others and share not only their interests but also the things they create. Academic interest in these trends has generated new terms such as ‘user-generated content’ and ‘produsage’, indicating how traditional relationships between cultural production and consumption are increasingly blurred in this environment (Burgess & Green, 2009; Bruns, 2008). There has as yet been no scholarly attention paid to the specialised music-related services and spaces that complement more generic infrastructures. These include e-commerce and promotion services allowing independent artists to connect directly with their audiences, such as Bandcamp, Tunecore and Reverbnation. Most relevant to the concerns of this paper, however, are new platforms supporting virtual collaboration, creative exchange on work-in-progress, and community-building amongst musicians themselves, such as Soundcloud, Ninjam, Indaba, Broadjam, Fandalism and the platform explored in this paper, Kompoz.com.

Kompoz.com provides an environment for collaboration and musical production, and also for initial consumption or audience connection, since both finished and in-progress songs can be streamed and listened to via the site. It should be noted that the focus in this paper is largely on ‘vernacular musicality’, paralleling Jean Burgess’s use of the term “vernacular creativity” (2006). These are the musical activities of amateur and occasionally semi-professional musicians, as they navigate the changing terrain of networked digital collaboration. Professional status and commercial ‘success’ are not primary objectives, and the participants in these activities might suggest that they are ‘not really’ musicians, or that these activities are hobby or leisure activities (Jackson, 2010; Gauntlett, 2011). As will be clear from the empirical discussion below, for the participants, the time to pursue their musical lives must be negotiated around work, family and other commitments.

As Turino points out, a multitude of music-related activities throughout the world do not involve formal presentation, recording, or commercial sales. These activities ‘are more about the doing and social interaction than about creating an artistic product or commodity’ (2008: 25). Turino goes on to argue that these participatory musical activities are not “lesser versions of the ‘real music’ made by the pros, but … something else – a different form of art and activity entirely”, and they should be conceptualised and valued as such (2008: 25). This paper follows Turino’s injunction to consider these activities on their own terms, and to see them as legitimate forms of expression and production. both music and technology are material, practical and embodied social activities, and so them together is of theoretical value.

From its very earliest manifestations music-making has had a technological basis, in the form of instrumentation and in more recent history, recording technologies, that require well-developed skill and expertise. Music-making is also an aspect of social and cultural life that is often innovative, usually collaborative, and which takes place in many different contexts, places and times (DeNora, 2000). The explorations described here therefore extend into the digital domain a long tradition of ethnographic writing about musical cultures, such as, for example, Ruth Finnegan’s classic ethnography of the musical landscape of Milton Keynes (2007).

Kompoz.com

Kompoz.com was founded in early 2007, and is a platform for musicians seeking to collaborate with other musicians, wherever they happen to be in the world. It is a purpose-built social network site with specialised features that allow site members to create workspaces for projects, upload and download tracks, create discussions around projects or individual tracks. Tracks are organised and grouped according to their role within the project: mixdown, drum, vocal, guitar, idea, PDF attachment, and so on. This specialised structure makes it easy for collaborators to see which components of the developing song project have been completed. Explorers of the site can find projects to contribute to in a wide diversity of musical genres (everything from blues, folk, rock to alternative, techno, house, and including several jazz genres and a small classical section).

Kompoz.com is, of course, not the only platform for cloud-based musical collaboration and indeed an enormous variety of other online and cloud-based technologies can be used for these purposes (Seddon, 2006). There are many musicians who now collaborate internationally with others who assemble the infrastructure they need to support their work by combining email, Dropbox, Soundcloud, Skype and so on. However Kompoz is a valuable site to consider because it puts together a comprehensive online toolkit for creative collaboration for music-making, taking projects from initial conceptualisation to the point where they are completed and ready to be presented to a wider audience via platforms such as iTunes, Facebook, Bandcamp, Reverbnation.

A full discussion of how the affordances of Kompoz compare with those afforded by alternative technologies is beyond the scope of this paper. Email and Dropbox, for example, can be used to transfer audio files. Limitations on email file sizes, however, may mean that it can be used to exchange compressed audio files (MP3s for example) but not uncompressed audio files (say in WAV format). Dropbox accommodates larger file sizes, but doesn’t facilitate discussion about different stages of development of the files making up a project. Soundcloud’s advantages include larger file uploads and timed comments on a single audio track, which are useful for discussion about progress on an evolving music project. These examples show how the specific affordances of interfaces facilitate some aspects of the process, but also limit their capacities for collaborators to create a comprehensive platform. It is therefore worthwhile, as a way into understanding processes and practices of cloud-based musical collaboration, to explore the structure of the Kompoz.com platform in terms of its affordances for this specialised activity.

After an overview of the platform and an introduction to how it works as a platform for collaboration and for community-building, the research methodology will be described. The remainder of the paper’s discussion focuses on how creative collaborations on Kompoz.com are mediated through the work-in-progress audio files that are uploaded to the site, along with accompanying annotation and discussion of them. In particular, it explores the ‘attached dialogue’ allowed for by the Kompoz platform, through the feature of adding comments to the audio tracks making up a project. I argue that this dialogue parallels those literacy practices observed by Ferguson, Whitelock and Littleton (2010) in university students as they collaboratively co-authored documents. These authors suggest that the joint production of knowledge was facilitated by this attached dialogue, leading to the documents worked on by the students functioning as ‘improvable objects’. These authors propose that the affordances of online environments for asynchronous communication make attached dialogue possible, and that this amounts to a new literacy practice:

The need to relate discussion to specific versions of improvable objects results in repeated use of evaluation, decision-making and compromise. Sometimes these are explicitly mentioned in postings, but many, particularly small issues … are presented in the different versions of the improvable objects.

(Ferguson, Whitelock & Littleton, 2010: 119)

Kompoz is an excellent community to take as a starting point for an exploration of the musical ecology of online collaboration, because it brings together and makes visible both the collaborative efforts and the products of its members. Music-making is, by its very nature, participatory, collaborative and communicative, and the relationship between individual creativity and collective innovation has always been complex and intertwined. Kompoz is centrally a community that relies on the sharing of expertise, experience and the creative efforts of others with complementary skills and knowledge. In this sense it can be thought of as a gift economy, in which each person contributes to the common purpose and also benefits from the contributions of others.

If we consider how collaboration for music-making in co-present situations is usually organised, it is clear that it requires a range of different creative, improvisational, communicational and social skills. The studio, rehearsal room or garage, along with the instruments, recording technologies and other material culture, provides an infrastructure for the interactions and activities of the participants. The process might start with someone contributing the germ of a song idea – a riff, melodic phrase, or lyric – which is then elaborated on by the participants. It might start with an improvisational jam that gradually evolves into a song. Or one of the participants may contribute a song more or less fully formed, that the collaborators work on to create an arrangement that they can rehearse to perform live or record. Over time, the song solidifies into the more or less stable configuration of its recorded form as included in a published album (though of course it can continue to evolve through re-recording and being played live).

As just described, the process is often conducted largely in synchronous co-present modes of collaboration, although there is also generally a component that happens individually and in private, between the times that the collaborators come together. Often specific phases of the development of a song from concept to recording will be undertaken by individuals working alone – lyric writing, for example, developing a guitar solo, over-dubbing vocals and other instruments. If for simplicity and convenience we envisage the process as having this general form, many of the stages of the process have parallels with what happens when some or all of it happens online, using largely asynchronous modes of interaction and collaboration. Thinking about the co-present scenario outlined above, however, we can see that moving the process online poses challenges to some of the kinds of activities that might happen in a studio, rehearsal room or garage context. Improvisational collaboration for example, requires high bandwidth connections and software that compensates for issues of latency, and indeed specialised services (such as Ninjam and eJamming) and research projects have focussed on providing these affordances (Brown & Dillon, 2007).

The Kompoz platform

Kompoz has been successful in attracting and retaining a vibrant and dynamic community of musical collaborators because it provides online alternatives to many of the affordances that are currently available. A Kompoz project usually develops as follows. An individual will upload an initial idea for a song, which might be a simple arrangement, an instrumental without lyrics or vocals, or a more well-developed multi-instrumental track. Most of the activity in this very vibrant and dynamic community is in public tracks that anyone can join and contribute to. It is also possible to create invitation-only private tracks, although it is impossible to estimate how much activity is hidden from public view in this way [1].

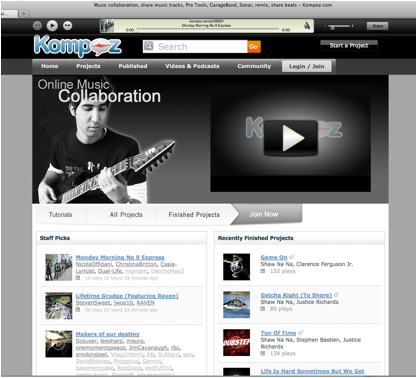

Figure 1. The Kompoz.com home page

The layout of the Kompoz.com home page makes the site’s architecture and navigation easy to comprehend. There is a prominent introductory video explaining how Kompoz works, presented by the site’s founder and CEO. The home page also clearly features access to tutorials, to give the first-time or inexperienced visitor confidence that this is a newcomer-friendly service, and the home page also prominently features a selection of completed tracks, either as ‘Staff Picks’ or the most recently completed songs (that is, songs that have been flagged by their creators as completed, and published within Kompoz.com). Site visitors can click on the links to listen to individual songs, or to access the profile pages of site members who have contributed to those projects.

Across the top of the screen is an embedded player, which streams music creating a kind of radio station from the site. The stream is largely context-specific to location on the site: from the home page the ‘Staff Picks’ are streamed, from the ‘Newest Projects’ page it is the most recently added projects that are played in turn, facilitating discovery of new projects by site members who are looking for projects to contribute to. From the ‘Published’ drop-down menu it is possible to create a customised ‘streaming radio’ station by selecting characteristics of the projects to be played from the genre, style and mood tags used to describe the track.

On joining the Kompoz community, members create a profile much as they would on any social networking site, giving themselves a user name, uploading a profile picture, describing themselves and their musical interests, and, importantly, giving their geographical location. It is possible for members to send a private message to any other member, though there is also a specialised action for inviting another member to collaborate on a specific project.

The majority of Kompoz.com content is publicly available, and the terms of service of the site specify that members can only upload material to which they themselves hold copyright. Kompoz is therefore unlike video sharing sites like YouTube and Vimeo, in that there is no commercial content delivered via the site (although the site is partially financed through advertising). Kompoz is primarily a platform for creators to collaborate and share their own productions with others. This means that all projects created on the site consist of original compositions as opportunities for collaboration. Copyright restricted material such as cover songs can be created, but require a closed-access invitation-only private project.

Although the main avenue for communication and collaboration on the site is via collaborative musical projects, Kompoz.com supports this activity as a custom-built social network site. Spaces for information and knowledge exchange are provided in the form of shared-interest groups (where members can interact with others who have a common interest in software, hardware platforms, musical instruments or kinds of music), and discussion forums.

My own involvement and participation in Kompoz.com commenced in February 2010. I came across the site while exploring as an aspiring amateur musician possible platforms for collaborating with people I already knew who lived in other parts of Australia. I created a profile and a private project, and also subscribed to some of the groups on topics I was interested in, including the ‘Everything Vocal’ group. Not long after I joined the site, a post was made to this group by someone looking for a vocalist to collaborate on a cover of Gary Numan’s 1980s hit ‘Cars’. I responded and received an invitation to join the project. That collaboration resulted in my contributing the vocal to a track which was published on iTunes in August 2011, under the name of a virtual band we called InVisible Minds.

Initially my interest in Kompoz was largely a private and leisure interest, but I could immediately see its potential as a rich research site for investigating online creativity and collaboration. Since 2011 my interest in Kompoz has expanded to an ethnographic exploration of the site as one of several environments for cloud-based musical collaboration. When I became interested in investigating Kompoz as a researcher, I amended my profile information to note that I am a university-based academic with a research interest in online creative collaboration and digital DIY culture (since my current research profile has this broader scope). I included a link to my academia.edu profile (which gives detailed information about my academic interests and professional affiliation, and includes downloadable copies of some of my publications). I also obtained ethics clearance for the project ‘Making Music in the Cloud’ (which includes Kompoz among several case studies). The empirical analysis reported in this paper forms part of this larger project (which is anticipated to result in a monograph to be published by Intellect in 2014).

Ethnographic research, by its nature, involves participation as well as observation and analysis. As a practice-based online community, full participation on Kompoz.com necessarily involves collaborating on creative projects and interactions. My ongoing involvement in the Kompoz.com site has therefore involved both creating musical projects for others to collaborate on and joining projects as a collaborator. As Porcello emphasises, the phenomenological character of both musical experience and ethnographic research are dynamic, unfolding in time, and built on encounter:

If ethnography is reminiscent of music in this respect, it might best be likened to an improvisational genre like jazz. … Like jazz improvisation, the success of participant ethnography is a matter of interaction and communication, shifting patterns of strangeness and familiarity, even practice

(Ferguson, Whitelock & Littleton, 2010: 119)

There are indeed similarities between becoming an effective ethnographic researcher and learning to make music in an ensemble:

Both require a certain technical familiarity at the outset (knowing basic research methods, being competent on an instrument or with one’s voice) but are ultimately dependent upon subsequent learning of effective, relevant, and locally meaningful patterns of coded social interaction – that is, performance skills

(Porcello, 2003: 269)

As a researcher, however, I am aware that the locally meaningful patterns of social interaction on Kompoz.com do not normally include interaction as researcher and research participant. I therefore carry ethical responsibilities towards other community members because my role is both as a participant and as an observer who communicates insights about the community to the outside world.

As the Association of Internet Researchers’ (AOIR) ethics guidelines point out, even though the content of an online site may be publicly available, those who participate in the site may reasonably perceive their interactions to be private (AOIR, 2012: 6). The structure of the Kompoz site can be considered to be a multi-layered nesting of spaces with differing understandings of ‘publicness’ and privacy associated with them. The new projects listing and discussion forums, for example, are readily accessible and frequented by the majority of active users of the site on a regular basis. They might therefore be considered to be ‘public’ parts of the site. In comparison, the interior activities of a project in progress, although publicly accessible in a formal sense, could reasonably be considered to be of interest only to existing and potential collaborators. These differing perceptions are central to the community’s shared understanding of the nature and purpose of the site. As my research into online musical collaboration has developed, I have therefore built up a network of participants (on Kompoz as well as other sites) who have agreed to be involved in the research, including those involved in the case study discussed here. It should be noted that, in alignment with research conventions, identifying characteristics of the case study project (such as the names of participants and tracks) have been changed to preserve the privacy of the participants.

The anatomy of a Kompoz project

Figure 2: Visibility of the activities of the Kompoz community – the collaboration stream

The collaboration stream, shown in Figure 2, makes visible the activities of others on the site – creating a sense of an active community where people are frequently listening to, ‘liking’ and commenting on the work of others, whether they are active collaborators or simply members of the community supporting each other.

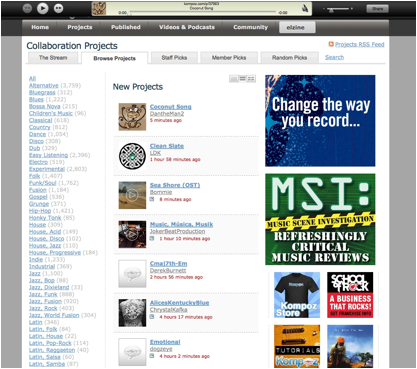

The project is the core object at the centre of the Kompoz.com ontology. The ‘Browse Projects’ tab, under the ‘Projects’ drop-down on the Kompoz home page, gives access to more than 27,000 projects created since the site launched. Figure 3 shows the ‘Browse Projects’ stream (headed ‘New Projects’ since the newest projects are listed first). As the Genres menu on the left makes clear, a wide range of musical form is represented on the site, though tending towards popular forms. Classical music, for example, is not well represented, though there are several varieties of jazz.

Figure 3: The ‘Browse Projects’ stream

There is an enormous fluidity in collaborative options: Kompoz projects often bring together unique combinations of collaborators. Rather than working over a long period together with a stable group of collaborators (as in the traditional ‘group’ formation), the affordances of online spaces support a more atomised set of conditions for individuals. An advantage of working with diverse collaborators in a site like Kompoz is the ability to benefit from skills an individual doesn’t have. This in turn allows individuals a kind of ‘creative freedom’ that they might not otherwise have.

Figure 4: The track listing for a typical Kompoz project

Figure 4 shows a typical track listing for a Kompoz project. Profile picture icons associate each track with its creator, and this particular project contains mixdown, drum, electric guitar, bass guitar, keyboard and vocal tracks, as well as a PDF attachment. The green icons in the ‘Status’ column indicate which tracks are ‘audition’ tracks, while the blue icons are ‘project’ tracks. When new tracks are uploaded to the project they are initially flagged as ‘audition’ tracks, until accepted into the project, when they become ‘project’ tracks. This shift in status is significant, and is an important affordance of the platform for managing credit attribution on projects. Only contributors who have at least one track accepted as ‘project’ tracks are listed as collaborators on the project when it is finalised. One track in each project can be ‘featured’ (indicated by a star in the ‘Status’ icon), and this is the track that is played from the ‘Browse Projects’ listing or when the cover art icon on the project overview page is clicked.

The three columns of figures on the right of the listing show, respectively, the number of plays for each track, the number of times it has been downloaded, and the number of comments attached to the track. Commentary on the tracks is the main medium by which collaborators discuss the progress of the project, exchange ideas about its direction. Commentary also allows members of the community who are not involved directly in the project to communicate with the project team.

Case study of a Kompoz project

The characteristics of Kompoz.com as a platform for creative collaboration and community-building can be explored in more detail by focusing on a particular project, ‘Stuck in a Jam’.

The project was created by Italy-based site member, Franco, adopting a set of lyrics created several months earlier by Canada-based member, Daria. Franco’s initial uploaded track consisted of a complete instrumental recording of the song. Although on the ‘Talent Needed’ section of the project overview page the default ‘Anything and Everything’ option had been selected, Franco’s initial upload was already well-developed and mainly lacked vocals. Table 1 lists the project tracks for ‘Stuck in a Jam’ in order by the date and time they were created. This will allow for an analysis of the commentary on the project – the attached dialogue on the tracks – in the order in which it unfolded.

|

Date |

Track/s |

Contributor |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

April 16 9:02pm UTC |

Stuck in a Jam [idea] |

Franco |

0 |

|

April 16 10:38pm UTC |

Stuck in a Jam full demo Corinne [mixdown] Stuck in a Jam lead Sep Corinne [vocals] |

Corinne |

30 0 |

|

April 18 |

stuckinajam [PDF attachment] |

Daria |

5 |

|

April 21 |

stuck in a jam with Corinne [mixdown] |

Duo-Jet |

23 |

|

June 11 |

SIAJ sample 1 backing sep Corinne SIAJ sample 1 full demo Corinne SIAJ sample 2 backing sep Corinne SIAJ sample 2 full demo Corinne [all vocals] |

Corinne |

0 3 0 5 |

|

June 15 |

Stuck in a Jam Mix02 [mixdown] Stuck in a Jam mix conventional [mixdown] |

Franco |

39 8 |

Table 1: Track listing in order of upload for ‘Stuck in a Jam’

In overview, the development of the project progressed as follows. The initial track was uploaded as an ‘idea’ by Franco at 9:02pm on April 16. The project overview page indicates that UK-based member Corinne had been invited to contribute vocals using a set of lyrics previously posted on Daria’s profile. Corinne responded extremely quickly, uploading her initial vocal audition only 96 minutes after Franco’s upload. A fourth collaborator, Duo-Jet, contributed a mixdown incorporating the vocal and instrumental tracks five days into the life of the project. Eight weeks later, Corinne uploaded four vocals tracks, two of them as ‘seps’ (the vocal only, with no backing, giving maximum flexibility for mixing) and two of them as a demo mix with the vocal and instrumental tracks, to give an idea of how the vocals sounded in context. Four days later Franco uploaded two mixdowns, one of which became the featured track on completion of the project.

The analysis below will explore how the intermediate stages of audio tracks uploaded to the project consist of improvable objects in the terms described by Ferguson, Whitelock and Littleton (2010). The conversations around the audio tracks served to give the collaborative creativity of the participants forward momentum by attaching critique and discussion directly to the digital audio artefacts representing the state of development of the project as it evolved. Ferguson et al. (2010) argue that, in fact, an online asynchronous communicational environment has advantages over a co-present synchronous interaction space, in terms of how participants engage with the intermediary stages of a piece of digital work-in-progress. The asynchronous environment provides participants with the time to reflect, evaluate evidence and consider opinions, whereas exploratory discussion in a synchronous setting requires participants:

… to do things quickly, producing immediate responses in a continuous conversation that may last for only a short time. In asynchronous settings, exploratory dialogue is more extensive and the improvable objects that act as the focus for these new literacy practices are often the product of many hours of work

(Ferguson et al., 2010: 119)

In a comment on the upload of her first vocal audition, for example, Corinne comments: “whew … what a day… I am so tired … me off to my bed … I so hope you like this Franco … but if not, I can sing again my friend … :)” [2]. Contributors will generally include a comment of some kind on their upload (though if several tracks are uploaded at one time they might not all have comments), giving others some context for it. It is very common for audition tracks to include a comment along similar lines to this one, saying that if this isn’t in the direction the project founder had in mind, that they would be happy to try something different.

Corinne’s note that it is very late in the day for her and that she is off to bed implies that she doesn’t expect to be online again for several hours. Kompoz collaborators can be anywhere in the world, and events within a project often move quite quickly, so it is not surprising that such indicators of people’s offline commitments and context are frequently seen. Daria also comments on the track, just two and a half hours after Franco’s initial upload, saying “OMG … I didn’t know you guys were doing this one … I am honored. This is very jazzy, I love it. Soooo fun!! I LOVE you guys, seriously :):).” Despite having said that she was going to bed, Corinne was still online to respond to this message, saying “Oh yes, and I love you too mate xxx you are such a wonderful friend xxx”.

Within the first eight hours after Corinne uploaded her vocal contribution, seven members of the Kompoz community who were unconnected with the project added supportive comments to the track including “Excellent Corinne”, “Such a great job”, “Awesome song, you have a terrific voice! The music is great”, “Excellent stuff”, “Nicely done!!”. While most of the interactions and activity on Kompoz are formally asynchronous, there are times, as seen here, where interaction happens in near real-time, when participants are online at the same time and several conversational turn-taking iterations can take place within a short time. The tone of this discussion is also very typical of those appearing throughout Kompoz, with superlative-laden language, strong encouragement, and ‘conversational’ forms of expression, including frequent ellipsis and exclamation marks, non-standard punctuation, spelling and capitalisation, and liberal use of smiley emoticons.

The track had already been commented on 14 times when Franco came online to comment to say “Wow… Corinne, you should always sing after a tiring day as yesterday!!! That is amazing :)”. Responding to the positive commentary and encouragement, Corinne posts soon afterwards:

oh, thank you so much Franco, you are a brilliant composer/musician and I love working with you!! hehe … and to my sweet friend Dar … we have worked together for quite some time now…and we have an amazing portfolio of work together

This comment confirms that Corinne and Daria had a history of collaboration: these community members have all therefore reached the point where they can refer to each other as ‘friends’. A few moments later Corinne comments further on how supportive the creative community of Kompoz is, addressing the various individuals who have posted in support of the project: “you all are such terrific talents, and I am so glad to be here with you all … it is humbling to know that you all stopped by and had a listen to Franco and Daria’s fabulous song!! Xxx”.

Four days later (on April 21), Duo-Jet (also from Italy) contributes a mixdown, which he explains in a comment has compression (“7:1 @ -23 db threshold”, as well as slap delay and plate reverb, to add “some spice”, as he puts it, to Corinne’s vocal). This specialised technical contribution is enough for him to receive a contributor credit for the featured mix of the song. Other than a comment by Daria on April 26 saying that she’d like to know when the final version is done because she’d “like to post it in a few places”, the activity on the project slowed at this point.

On May 1, a community member who wasn’t involved in the project commented “Great tune, all. Really a lot of fun!”. When new content is added to a project, a notification is sent by email to all participants, and so this comment prompted Corinne to post two more over the next hour, the first one simply saying thank you, and the second saying ‘I still need to do a wee bit of backing on this. I will as soon as I’m able’. Three weeks later she added another comment: “Doing backing this week to get my part done … sorry taken so long … cheers to all xx”. At this point it was around six weeks since the project was initiated and the initial flurry of activity of the first few days.

A few days later, on June 5, Corinne posted (as a comment on Duo-Jet’s mixdown), “What do you think I need to add to this Franco? I will do it tomorrow so we can finish?”. Franco responds, “I think it is already awesome as it is. Go ahead with other songs :)”. Daria has an idea for additions, however:

In the ending where the lyrics say ‘he is my destiny’, etc. I’d love to have some of those same Oooo’s you did at about 1:09, they were incredible. And, it needs something vocally in the very outro and possibly behind the spoken word. And, I’m just thinking vocal sounds here, no words. Something different. […] Try something you’ve never tried before!! Let’s be visionary here … this is one of the best songs we’ve done, let’s make it extraordinary.

Corinne responds on June 8 that she agrees that these are great ideas and will see what she can do: “I am going to add a bit here and there, to lift the song in places … I will follow what Dar said as best I can”. She goes on to explain that she has other offline commitments but will try to get the recording done over the next 24 hours. She comments that she has been particularly inspired by this project to try something different: “I had so much energy when I sang this!! the music, the lyrics, they were and are an explosive combination that forced me out of my shell and finally I took some chances!!”.

As these extracts from the conversation about this song describe it, Corinne’s creative energy and imagination had been galvanised by her embodied interaction and improvised physical and vocal response to the input she had received from the others. Schrage points out that “creativity often builds on the shards and fragments of different understandings. … we don’t just collaborate with people; we also collaborate with the patterns and symbols people create” (1990: 41). We see in these exchanges between the participants in the ‘Stuck in a Jam’ project, evidence of creativity in relational, interactional and material terms. None of the participants is able to complete a project of this kind by themselves, and each is inspired to explore capabilities and ideas that they would never have attempted alone. In material terms, working within the medium of digital music production requires a networked technological infrastructure that is distributed between home studio (with its microphones, musical instruments, audio interfaces and computers), via the cloud-based servers, software, networking equipment and interface of Kompoz, with the loop being closed with the internet connectivity and audio playback equipment in the home studio of co-participants.

Corinne uploaded four new backing tracks to be added to her original lead vocal on Thursday June 12 (labelled ‘sample 1’ and ‘sample 2’ and provided in both ‘sep’ and ‘demo’ forms, as before). She comments on the ‘sample 2 full demo’ track:

whew… long day. Ok, I have uploaded two different backings for you to choose from. […] feel free to use what you want and cut away the rest, or cut from one sep and add to another, or use both for a layered effect. Or, if you all think we do not need backing, then that is fine too.

Her comment indicates that she has tried to experiment, knowing that some of what she has done may not be used. After Franco has responded to say ‘thank you’ and that he will upload a mixdown as soon as he can, Daria responded “Took a very quick listen Corinne, I’m loving it. Will try and listen again tonight. I only had three hours sleep and I’m rushing to work.”

On the ‘sample 1 full demo’ track Corinne commented:

the bridge part is my favourite in this….I think we could drop the beginning late again thing and the long ooooooo to start? or we can just get rid of all the backing … as you can tell, I am NO mixer lol … so in this raw state, it sounds horrible cause everything needs readjusting, so I wait for franco [sic] to work his magic …

Corinne’s comment emphasises that she thinks she has provided a diversity of material for her collaborators to select from: “when you listen, dont [sic] forget there are two versions. I think I like the first best, but not sure … I need everyones [sic] honest opinion, ok?” In this piece of attached dialogue, Corinne is offering critique and making suggestions about how to try combining the two versions, taking parts of each and combining them to take the project forward. Franco responds that he needs to listen to both tracks a few more times before he can make a choice: “at the moment I can’t take a decision since I like both”.

Four days later Franco uploaded two separate mixes of the song, one of which (‘Mix02’) was designated the featured track. Commenting on the first mix, Franco says:

Corinne, consider this mix just as a crazy experiment … may be too crazy. I used both your backing tracks and also detuned them. Let me know …

Corinne’s response is supportive of trying to do something innovative: “hahahahaha!!! Its Crazy!! I love it!! lets keep this one, and do another mix to compare it to … eh? we shall see what Daria has to say also”. Daria’s response seems a little more ambivalent: “Very interesting. There are definitely a lot of elements I love in this. It makes it very modern sounding … cool … absolutely love it ! Sure, I’d love to hear another mix too, just because :).” Around 10 days later Daria followed up: “Okay, after a rest for my ears … this is definitely the mix I personally like and the one I will be using when I get a chance to post.” Franco comments that he prefers Mix02 over the other but says he will let the others choose which version should be the featured version, Corinne also prefers the more experimental version and consensus is reached when Daria says “@Franco, can we make this version the feature song :)”.

At this point the project reached a point of stabilisation, and the collaborators themselves clearly felt that this featured version was the point of culmination of the project.

Conclusion

The impulse towards the kinds of activities which take place on Kompoz can be seen to parallel the DIY craft activities of amateur makers working in a range of media whose:

… pursuits are substantial enough for them to engage in the long-term acquisition of a range of special skills, knowledge, and experience, as well as acquiring and maintaining the material resources of tools, machines and work spaces necessary to achieve the standards they seek.

(Jackson, 2010: 19)

On Kompoz there is visible engagement with skill-building and the development of knowledge, acquisition of tools, materials, and specialised spaces, which creates a powerful sense of purpose in otherwise voluntary activities. It may be that these processes of personal investment and engagement with the physical and sensual qualities of the material world, are ultimately more important for the participants than the artifacts they are engaged in producing. Jackson points out that although these activities could, in some respects, be regarded as forms of labour, sometimes involving demanding and unpleasant obligations, they are “also a form of pleasure seeking – a quest for sensation and emotion” (22). The attached dialogue associated with the tracks of ‘Stuck in a Jam’, as we have seen, are full of evidence of sensation, emotion, and pleasure for the participants.

It is also important to emphasise that these activities involve creativity in material and process-based terms, even when the materials that are worked with exist largely in the digital domain. For Morris, creative making (in the field of visual arts, at least) is a certain kind of behaviour: ‘a complex of interactions involving factors of bodily possibility, the nature of materials and physical laws, [and] the temporal dimensions of process and perception’ (1993: 75). Corinne’s account of her initial vocal recording – riffing off the lyrics and instrumental recording she had downloaded from Kompoz – speaks of just such a complex and technologically-mediated improvisation at the interface between perception and the production of the voice.

The cloud-based creative collaborations taking place on the Kompoz platform can be thought of as a kind of choreography of action: people, technologies, domestic spaces and digital objects interacting with each other in a way that ‘evolves’. Like a dance, in which ideas become objects and objects become ideas, this is ‘material thinking’ in Carter’s terms (2004). Indeed Carter suggests that the materials that are worked with in creative expression are themselves creative: “There is a reciprocity between creativity and the materials that creativity works upon: to be workable these materials must also be creative” (183). By creating the space of the project as one which holds the audio files making up the separate contributions of its participants, the Kompoz platform allows the tracks and the project to become a work of art in the sense that Carter defines it: “The work of art may be a machine for recombination” (183). The material or psychic elements interact to form new elements, which each have their own “propensity for recombination”. Collaboration between people, therefore, is dependent on such an ‘inclination to meet and mould’ existing in the materials to hand (Carter, 2004: 183). This ‘workability’ of the materials must necessarily be recognised by potential collaborators, even when the only means of interacting with the creative offering of someone else is a streaming digital audio file.

Crawford has called for a revalorisation of ‘manual’ forms of work and expertise, on the grounds that creativity “is a by-product of mastery of the sort that is cultivated through long practice” (2010: 51). Manual competence entails a stance towards the built, material world that is active and cognitively complex, and which engages with the experience of making and fixing things. As Crawford insists, “skilled manual labor entails a systematic encounter with the material world” (21). After all, as Crawford argues, thinking is bound up with action, and therefore “the task of getting an adequate grasp on the world, intellectually, depends on our doing stuff in it” (2010: 164). There is an opportunity, therefore, to deepen our understanding of the infrastructures necessary to support creativity and collaborative innovation in distributed networks, through thinking about how both music and digital technologies mediate our ability to improvise in the social world.

Endnotes

1 Each project is given a sequential identification number when it is created. The oldest project on the site was created on 21 February 2007 by the founder and CEO of the site, Raf Fiol, and was given the ID 1007. The ‘Browse all Projects’ listing contains more than 27,500 projects. In 2008 and 2009 an average of around 19 projects per day were created, with the average over 2011 being 20.6 and 2012 as 21.2. In 2013, projects are being created at the rate of around 20 per day. This suggests that the Kompoz community is fairly stable at around this amount of activity. A caveat, however, is that many projects do not, in fact, attract collaborators and remain at the initial idea stage. Because of the volume of new projects being created, collaborators tend to join a project relatively quickly, within the first day or two. Once a project is no longer in the first few pages of the ‘New Projects’ stream, it becomes less likely that it will attract collaborators. Projects may sometimes be ‘unearthed’ from much earlier in the stream, and in fact the project analysed here was created by its originator in response to a lyric posted by another community member around a year earlier.

2 Typography and spelling have been preserved in transcribing comments.

References

Association of Internet Researchers. (2012). Ethical decision-making and internet research: Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee (version 2.0). Retrieved from http://www.aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf.

Bloustien, G., Luckman, S., & Peters, M. (Eds). (2008). Sonic synergies: music, technology, community, identity. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Brown, A. R., & Dillon, S. (2007). Networked improvisational musical environments: Learning through online collaborative music making. In J. Finney and P. Burnard (Eds.), Music education with digital technology (pp. 96-106). London: Continuum.

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and beyond: From production to produsage. New York: Peter Lang.

Burgess, J. (2006). Hearing ordinary voices: Cultural Studies, vernacular creativity and digital storytelling. Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies. 20: 201-214.

Burgess, J. E. & Green, J.B. (2009). YouTube: online video and participatory culture, Cambridge & Malden: Polity.

Carter, P. (2004). Material thinking: The theory and practice of creative research. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing.

Cherry, G. E. (1984). Leisure and the home: a review of changing relationships. Leisure Studies, 3(1), 35–52.

Crawford, M. B. (2010). Shop class as soulcraft: An inquiry into the value of work. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

DeNora, T. (2000). Music in everyday life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ferguson, R., Whitelock, D. & Littleton, K. (2010). Improvable objects and attached dialogue: new literacy practices employed by learners to build knowledge together in asynchronous settings. Digital Culture & Education, 2(1), 103–123.

Finnegan, R.H. (2007). The hidden musicians: Music-making in an English town. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Gauntlett, D. (2012). Making is connecting. The social meaning of creativity, from DIY and knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0. Cambridge & Malden: Polity.

Green, L. (2002). How popular musicians learn: a way ahead for music education. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate.

Jackson, A. (2010). Constructing at home: Understanding the experience of the amateur maker. Design and Culture, 2: 5–26.

Katz, M. (2010). Capturing sound: How technology has changed music. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Morris, R. (1993). Continuous project altered daily: The writings of Robert Morris. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

O’Shea, H. (2012).‘Get back to where you once belonged!’ The positive creative impact of a refresher course for ‘baby-boomer’ rock musicians, Popular Music, 31(02), 199–215.

Schrage, M. (1990). Shared minds: The new technologies of collaboration. New York: Random House.

Seddon, F. A. (2006). Collaborative computer-mediated music composition in cyberspace. British Journal of Music Education, 23(03), 273-283.

Turino, T. (2008). Music as social life: The politics of participation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

About the author:

Elaine Lally is Associate Professor in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Technology, Sydney. She is a member of the Communication Studies academic group and of the Creative Practice and Cultural Economy research strength. She researches in the areas of creative practice and digital culture. Her work is empirically grounded and draws on the academic fields of cultural studies, material culture, consumption and everyday life, and the sociology and philosophy of technology. She is the author of At Home with Computers (Berg, 2002) and co-editor of The Art of Engagement: Culture, Collaboration, Innovation (University of Western Australia Publishing 2011). In 2012 she prepared a research report on women and creative leadership in the Australian Theatre sector, commissioned by the Australia Council for the Arts. A monograph on her current research on online musical collaboration, provisionally titled Music-making in the Cloud: Creativity, Collaboration and Social Media is under contract with Intellect for publication in 2014.