Self-writing a movement and contesting indigeneity: Being an Aboriginal activist on social media

Theresa Lynn Petray

James Cook University (JCU), Australia

Abstract

Social media offer the potential to creatively rethink and amend social practices. Because everyone (that is, those with access) can write themselves into being, they can determine the way their identity is outwardly demonstrated. This potential is especially interesting for activists – the construction of salient social movement identities is a key component of movement strength. Identity though, is not a unitary thing and activists may identify with a number of causes and issues. Using online means, the process of identification can be complicated, and this can lead to ambiguity. Activists are also limited by the space provided on their chosen platform/s, their ability to reach an audience, and the attention span of that audience. This paper focuses specifically on the use of social media by Aboriginal activists in Australia. Aboriginal activists embrace the ambiguity offered by social media to challenge mainstream imagery and self-write alternative understandings about what it means to be Indigenous. The agency of Aboriginal activists is both enabled and restricted by the social media they use, and social media allow for the continuation, expansion, and transformation of various ‘traditions’, from traditional language to traditional activism.

Introduction

Social media technology has become ubiquitous and is now embedded in many aspects of social life, including activism and protest. Social media has been credited with a prominent role in many recent protests and uprisings: the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, the Iran election protests in 2009, the anti-junta protests in Myanmar in 2007, as well as activities not traditionally recognised as protest, such as Wikileaks and ‘hacktivism’ by Anonymous. There is some debate about the centrality of social media to these events, but it is clear that activists are increasingly using technology as a tool of protest (Sauter & Kendall, 2011). Social media – that is, online spaces where users generate content, such as Twitter, Facebook, blogging, and video- and photo-sharing sites – have been useful for organising events (Kavada, 2010), publicising to a wide audience (Lim, 2012), and spreading the message independently of the mainstream media – print, radio and television journalism (DeLuca, Lawson & Sun, 2012). This paper is most concerned with the use of social media for the latter activity of spreading the message – a textual form of activism which attempts to construct the movement in particular ways. As with earlier tools of communicating social movements, such as letters to the editor, brochures, and meetings, the technology enables activism, but it also constrains what can be done. As activists come to increasingly rely on social media as a tool of protest, it is important to understand the ways it enables and restricts activism.

Although activists still rely on the mainstream media for publicity, they are not entirely dependent on it. A key change offered by social media is the ability for activists to write their own stories, and for these stories to be disseminated to a wide audience. Unlike community-based radio, newspapers, and television, social media is inexpensive and immediate. Activists can blog and tweet, share photos and videos, and craft their own image for anyone to see. This form of ‘self-writing’ is a ‘technology of the self’ (Sauter, 2013; Foucault, 1988) which can be harnessed for collective identity-building. They are bound up with offline processes of self-formation – identities are developed in both domains. In the same way that individual selves are worked out through these technologies, this paper argues that collective selves, such as social movement identities, are developed. Collective identity is what makes activists feel like they belong to a social movement (Klandermans, 2007: 364). Snow (2001) refers to collective identity as “collective agency”, and it is this sense of “we-ness” (Hunt & Benford, 2007) which sustains activism over long periods of time.

This paper uses the example of the Aboriginal movement to examine the way that social media contributes to collective self-formation by activists. I use the unifying term, the ‘Aboriginal movement’ (following Burgmann, 2003; Mansell, 2003) despite the diverse nature of Aboriginal activism in Australia. In the same way that people refer to the diverse collection of ‘green’ ideologies as the ‘environmental movement’, or the many waves and varieties of feminism as the ‘women’s movement’, Aboriginal activism can be united under the same term. As Merlan (2005: 488) puts it, all of the well-documented Aboriginal movements are focused on “problematic relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples”. Social movements, like the Aboriginal movement in Australia, can use online self-writing strategically, to actively construct a collective identity. But more often, social media is used in a mundane way by participants.

This more subtle and less explicit use of social media is still an important tool for social movements. This paper focuses on this online self-writing of an Indigeneity which deconstructs essentialist assumptions and establishes more complex individual and collective identities. Those who consider themselves activists may use social media for reasons that are not explicitly political, but their identity as ‘activist’ is constant. Moreover, these Aboriginal users of social media attract ‘followers’ because of their activism. Thus, even social media usage which is not ‘political’ as such contributes to the self-writing of the movement. Social media give social movement actors the ability to self-write their collective identities in more nuanced ways, as compared to times when they relied more heavily on mainstream media representations of the movement. For Aboriginal activists, this online self-writing of collective identity allows for static and stereotypical notions of Indigeneity to be challenged, and for more complex versions to take their place.

I refer to online ethnographic research which I began in July 2011 and which is still ongoing, for which I followed and participated in conversations with Aboriginal [1] social media users who consider themselves activists. The ethnographic material on which this paper draws comes from public social media sites, primarily Twitter. Before submitting a draft of this manuscript, I contacted all participants included here, and provided several options: they could be included with attribution; their comments could be included anonymously; or they could withdraw their comments from the paper. I followed this up by sending a draft of the manuscript. Several participants responded with comments and feedback, which I incorporated. This paper will first examine how self-writing is used by Aboriginal activists to develop and maintain social movement identities. I then consider the way that Aboriginal activists use social media to construct a less essentialised idea of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia – for them, a form of activism. Finally, I explore the relationships which are ‘written’ and rendered visible through social media.

Collective Identity Formation

In November 2012, Federal Opposition Leader Tony Abbott made the following statement:

I think it would be terrific if, as well as having an urban Aboriginal in our parliament, we had an Aboriginal person from central Australia, an authentic representative of the ancient cultures of central Australia in the parliament.

(as reported in Vasek, 2012)

Abbott’s statement suggests that there is a dichotomy, that an Aboriginal person from an urban area is precluded from being authentically Aboriginal. The weekend before making this statement, Tony Abbot described MP Ken Wyatt, an Aboriginal member of the Liberal Party, as a “good bloke” but “not a man of culture” (Vasek, 2012). Abbott’s comments received considerable backlash, but represent widespread understandings of Aboriginal people in cities as divorced from culture and tradition and as somehow less ‘authentic’ than their remote counterparts. Paradies (2006: 359) describes how his physical appearance, which does not match the stereotypical look of Aboriginality, leads to “intense questioning of authenticity”. Appearance, location, and everyday practices which do not fit into the narrow view of what many people expect of Aboriginal people are considered suspect, and are thought of as not really Aboriginal.

In fact, Aboriginal people themselves have relied on certain positive stereotypes as a means of strengthening their political movement. According to Paradies (2006: 356), this “goal of creating a distinct, coherent and thus relatively homogeneous pan-Indigenous social and political community” has been an empowering tool of survival. This strategic essentialism (Spivak, 1988) is not unique to Aboriginal Australians – many other Indigenous groups around the world use essentialist notions of themselves to their advantage (e.g. Speed, 2006; Landzelius, 2006). Strategic essentialism is an internal tactic that communicates similarity within a group, and it is an external tactic that sets a group apart as special and unique (and sometimes creates that group to outsiders).

In Australia, showing the links between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ or ‘tribal’ Aboriginal peoples has been an important builder of collective identity on a nation-wide scale. Aboriginal academic Marcia Langton (1981) wrote scathingly of anthropologists who ignored the similarities between these three groups, arguing that even ‘urban’ communities are characterised by some kind of ‘Aboriginality’. She suggests funerals and internal conflict resolution as just two instances of the complex culture maintained in urban Aboriginal settings (Langton, 1981:17). In fact, Langton (198: 19) argues that maintaining a sense of Aboriginality provides a sense of security amidst the hostile white society and offers a ‘ ‘sane’ way of negotiating the demands of an ‘insane’ society”. Pan-Aboriginality, then, is a concerted framing tactic which posits all Aboriginal people, even those living outside of ‘traditional’ contexts, as worthy of ‘preserving’. However, this paring away of complexity feeds into mainstream misunderstandings of what it means to be Aboriginal, as evidenced by Tony Abbott’s statements.

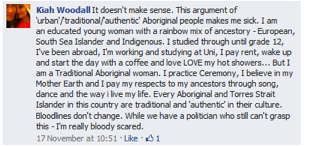

Aboriginal activists use social media to counter these essentialised understandings of Indigeneity. Kiah Woodall, a young Aboriginal woman, is in a progressive Facebook group called ‘The Revolution’. Kiah responded to the story about Tony Abbott’s understanding of Indigeneity with this:

Image 1: Facebook comment in group ‘The Revolution’ by group member Kiah Woodall.

Image used with Kiah’s permission.

In this comment, Kiah explicitly reflects on the complexity of her Aboriginality. She points out that she has mixed heritage, that she has travelled overseas, and that she appreciates the comforts of modern society. However, none of this takes away from her identity as an Aboriginal person. More importantly, she moves from her individual assessment of herself to a broader discussion of “every Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander in this country”. This construction of Indigeneity as always traditional and authentic is an important means of challenging essentialism. A number of Twitter users responded to Tony Abbott’s statements with humour rather than Kiah’s anger, tweeting with #Itriedtobeauthenticbut followed by jokes about their lifestyles (and this story was picked up by the mainstream media).

A social movement is a collective action against a perceived inequality. Snow, Soule and Kriesi (2007: 3) provide this definition of social movements:

Social movements are one of the principal social forms through which collectivities give voice to their grievances and concerns about the rights, welfare, and well-being of themselves and others by engaging in various types of collective action, such as protesting in the streets, that dramatize those grievances and concerns and demand that something be done about them.

Social movements are differentiated from formal politics because they happen “outside the sphere of established institutions” (Bukstein, 2008: 124). Although using social media to express anger does not make a social movement, it is one way that a pre-existing movement can dramatize their grievances, as well as express identities and self-categorisations. Social media groups and #hashtags offer the Aboriginal movement new ways to express their collective grievance with racism and essentialism. When individual activists do so, this feeds into movement demands that something be done.

Collective identity is the shared definition of “us versus them” as perceived by participants in social movements. Klandermans (2007: 364) distinguishes between personal identity – ‘all these different roles and positions a person occupies’– and collective identity – ‘a place shared with other people’. A shared identity is vital to the longevity of social movements because it gives activists a sense of purpose and belonging (Snow et al., 2007; Friedman & McAdam, 1992). When people feel like they are part of something, they are more likely to remain committed even during quiet periods and after setbacks (Hunt & Benford, 2007). By forging a strong group identity, and positing ‘activist’ identities in opposition to a common ‘enemy’, social movements have the potential to effect social and political changes (Burgmann, 2003). In the case of Aboriginal activism, collective identity established through writing on social media about self, day-to-day practices and wider current affairs and social activity works to contest (stereotypical) identifications, deconstruct essentialising understandings of Aboriginality and establish alternative individual and collective Aboriginal identities. It also builds connections between people who might not otherwise meet, and in some cases encourages a move from ‘push-button activism’ to more formal social movement participation (Petray, 2012a).

Movements often mobilise identities that are already salient for people, such as gender or race. The factor which differentiates Indigenous movements from others is the unique cultural and racial (Cowlishaw, 2004) identity shared by movement participants. This is not to say that there is cultural sameness across Aboriginal Australia, nor that all members of the Aboriginal movement come from a singular background. There are a number of different identities occupied by activists in the Aboriginal movement (Petray, 2010; Maddison, 2009; Merlan, 2005; Rowse, 2000). However, they are united by their sense of being Aboriginal. One’s Aboriginal identity may not be chosen, and it may be socially constructed (Morris 1997), but it is integral to a sense of unity. As Cowlishaw (2004, p.60) points out, ‘racial identities are powerful and positively significant’. Moreover, ‘Indigeneity’ links activists into a global network, which they may not utilise but to which they feel a sense of belonging (Merlan, 2009).

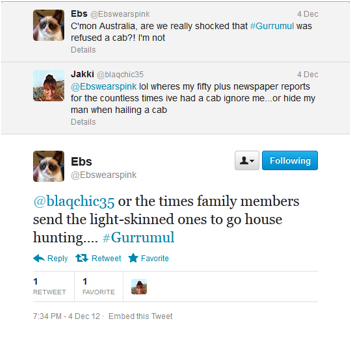

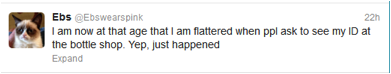

In addition to challenging stereotypes about who is Indigenous and what that means, social media users also use the space to point out the racism that they experience. Twitter user @Ebswearspink had the following conversation:

Image 2: Twitter conversation between @ebswearspink and @blaqchic35.

Image used with @Ebswearspink’s permission.

These comments on Twitter respond to a story about Aboriginal singer, Gurrumul Yunupingu, who was refused service when he ordered a cab after a concert in Melbourne. In this short exchange, Ebs makes the point that this manifestation of racism is not isolated. In a longer discussion of racism, Blayke Tatafu writes about an ongoing interaction with his boss. This began, he writes, with her comment: “Oh! You are very smart for an Aboriginal person. I am surprised.” It culminated in a conversation that left Blayke feeling disempowered and victimised:

I stood there with my personal space and freedom abused and violated, all from a woman I had high regard for. I felt myself breaking with no power whilst still being abused for all sorts of inaccurate reasons. I started to do the very thing I promised myself not to resort to… cry. I felt akin to my people in the way they were treated by British invaders (far less of course) and I could no longer handle the abuse. I stood there, a 7 foot, 19 year old man crying; my confidence and power stolen

(Tatafu, 2012c: n.p.)

This self-writing is not just used by Blayke to make sense of his own position within the complex workplace and a racist boss. He also makes the connection to the original invasion of Australia by British settlers, and draws similarities between that experience and his own. These conversations on social media work to construct a collective identity for Indigenous people as still struggling against racism, and they attempt to communicate the prevalence of everyday racism as well as the effects it has on its victims. This is important work for the formation of a social movement identity for both participants and observers of this movement.

However, even movements which arise from pre-existing shared identities like gender or race need mechanisms to solidify and maintain that collective identity. So, for example, although the Aboriginal movement has a clear, pre-existing community from which to draw constituents, being Aboriginal does not inherently come with an activist identity. That must be developed through movement activities such as protests (Blumer, 1969), other forms of collective action, or they can find alternative ways such as self-writing on social networking sites. Collective identity must be continuously created and negotiated, and individuals need to share that movement identity, and self-writing can be part of this process.

Challenging Essentialism

Following the work of Brubaker and Cooper (2000), this paper recognises that ‘identity’ is not a singular concept. Rather, we can think of identity as multi-faceted. For the purposes of this paper, the more active terms of ‘identification’ and ‘categorisation’ are useful. They indicate that we cannot think of ‘identity’ as static, reified, and somehow separate from social reality. Identification is a process undertaken by agents, and is flexible depending on context and may change over time. Identification can be relational, based on relationships with others, or categorical, based on ‘membership in a class of persons sharing some categorical attribute’ such as race, gender, and so on (Brubaker & Cooper, 2000: 15). Categorisation, on the other hand, is imposed by others, and includes “the formalized, codified, objectified systems of categorization developed by powerful, authoritative institutions” (Brubaker & Cooper, 2000: 15). This power to name has been demonstrated within the Aboriginal context in Australia. Distinctions between ‘full-blood’, ‘half-caste’, ‘quarter-caste’ and ‘octoroons’ had very material impacts on Indigenous families, and led in far too many cases to the removal of children from their families and communities (Reynolds, 2005). Australian states like Queensland used ‘exemption’ cards to further categorise certain Aboriginal people as ‘acceptable’ according to white standards, with material evidence to prove their ability to live ‘off reserve’ (Dodson, 1997). The government continues to define what “Aboriginal” means, albeit in a way that relies more heavily on community-based definitions (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2005).

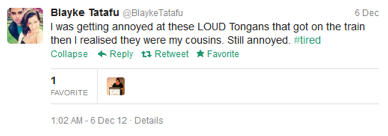

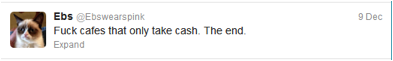

Because social media have become so embedded in our lives, most of the self-writing that goes on is mundane and does not explicitly engage with stereotypes. This non-reflexive self-writing of Indigeneity is no less important for challenging essentialism, however. It still acts as a technology of self-formation, though this function is more latent. @BlaykeTatafu, for example, refers in a mundane comment about public transport to a similar sort of “rainbow ancestry”, in Kiah’s words above.

Image 3: Tweet by user @BlaykeTatafu.

Image used with @BlaykeTatafu’s permission.

Griping about public transport is a common topic on social media, but in this everyday post Blayke constructs himself as coming from a multicultural background. Blayke raised similar issues of multiculturalism on his blog, Halcyon Days. In his introductory post, he writes that “I am an Aboriginal and Tongan-Hawaiian boy/man. My mother’s family (Smith) are from Trangi (Wiradjuri) and Kempsy (Daingatti) and Dads heritage comes from the Polynesian Island’s of Tonga and Hawaii. I am proud of my culture and of my people of it” (Tatafu, 2012a: n.p.). Here, he is more reflexive about multiculturalism than in his tweet. He applies this reflexivity not only to himself, though. In a music review of Jessica Mauboy, he writes that

Jessica is of Aboriginal and Indonesian descent to which without hassle, she has a cultural responsibility. She has a cultural awareness that makes Jessica seem like she’s not a famous pop star, but your mate that you could find at any BBQ, knocking the froth off a few stubbies out the back (Tatafu, 2012b: n.p.).

Multiculturalism is an important aspect of what it is to be Indigenous in contemporary times, so these conversations work to identify Aboriginal people as ‘authentic’ even when they have a ‘rainbow mix’ of heritage.

Self-writing is an historical “technique of self” (Foucault, 1988) used by people to “form understandings of their place in the complex realities they exist in” (Sauter, in press: 2) [2]. Identity statements communicate ‘who I am’ to the audience (Zhao, Grasmuck & Martin, 2008). That is, self-writing allows people to reflexively ‘identify’, rather than (or sometimes in direct opposition to) being ‘categorised’. Self-writing is inherently agentic, whether the identification process aligns with or diverges from an externally-imposed categorisation. Reflecting Brubaker and Cooper’s (2001) discussion of identification as a process, rather than a noun, self-writing (especially through social media) is constant and consistent, an ongoing process of self-formation (Sauter, in press: 16). This function of social media in itself challenges the tendency towards essentialism that is often experienced by minority groups in the process of categorisation – by constantly communicating and self-forming through social media, any ideas about static identities are discarded.

Social media are not a neutral platform for self-writing. Importantly, social media exist as both tools of protest, but also as spaces for protest (Lim, 2012). Social media are content-less without users, so sites like Twitter and Facebook “only exist as the continual creation of millions of participants” (DeLuca et al, 2012: 501). However, as Lim (2012) points out, they are not simply neutral tools to be used or adopted by social movements, but rather influence how activists form and shape movements. It is necessary to acknowledge the constraints placed upon users of social media, by the corporations and companies who own them, by government regulations, and by the technologies required to use them. Online self-writing happens in spaces which are owned by corporations who set the rules of behaviour, which users must learn to navigate (Sauter, 2013: 183). For example, Twitter, by confining content to 140 characters-or-less, creates an expectation that expression on the site be brief, succinct, or partial. It is possible to subvert this limitation to some degree, for example by posting longer comments spread out over several tweets or by linking to longer posts on blogs or websites. Sauter (in press: 17) argues that the brevity demanded by social media reflects new ways of communicating, and in fact that “technology and human behaviour come to shape one another in relations of reflexivity”. Further, interactions online are still largely governed by offline norms of communication and interaction. Although identity formation in online environments is ‘disembodied’, many important forms of self-writing happen in ‘nonymous’ (as opposed to anonymous) environments where relationships with ‘friends’ or ‘followers’ are not strictly limited to online contexts. Thus, self-performance is still constrained by established social norms (Zhao, Grasmuck & Martin, 2008).

It is important to remember that what social media offer is not something new – Sauter (in press) and Foucault (1988) both discuss the long history of self-writing as a technique of self. Aboriginal people have practised self-writing for decades, especially making use of autobiography to tell their own stories, to challenge white-washed views of history, and to upset stereotypes of Aboriginality. Anita Heiss’s (2012) book Am I Black Enough For You? explicitly challenges static notions of Indigeneity. Likewise, activists have practised self-writing in the past, making use of pamphlets and brochures, letters to the editor, protest songs and slogans, and posters to ‘form understandings of their place in the complex realities they exist in’ (Sauter, in press: 2). Writing has been an important ‘self-forming’ (Sauter, in press) tool around the world for centuries, but as this self-writing moves online, it becomes mundane and accessible. Speaking about individuals, Sauter (in press: 15) says that “modern subjects employ [social media] as one tool through which to make themselves public, work on themselves, talk about their problems and weigh up costs and benefits of future conduct”. Again, social movements undergo a similar process as collective entities, using social media as just one method of publicising their cause, solidifying their identity, and planning for the future.

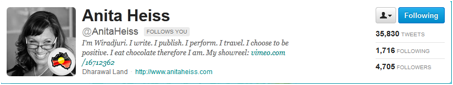

Aboriginal social media users are not only engaged in conversations about Indigeneity. This public discussion of other issues continues the process of self-formation which challenges essentialist notions of Indigeneity. This is perhaps most telling in the profiles of social media users. The following profiles all present Indigeneity as just one component in the process of identification.

Image 4: Twitter profile images from four Aboriginal users.

Images used with users’ permission.

Although Aboriginal imagery or terminology is prominent in all of these profiles, it is not the only thing. Also present is the degree being studied, musical tastes, union membership, appearance, interests, and personality traits. These factors are all considered to be just as worthy of mentioning, indicating their importance in the formation of self through the writing of these profiles.

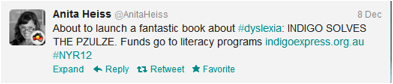

Other interests and characteristics are also prevalent in the tweets people post. @AnitaHeiss shows her commitment to improving literacy with tweets like this one:

Image 5: Tweet by @AnitaHeiss.

Image used with @AnitaHeiss’s permission.

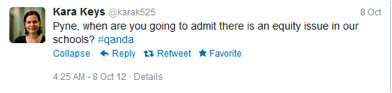

@Karak525 engages in a conversation about education in response to comments made on ABC’s Q&A:

Image 6: Tweet by @karak525.

Image used with @karak525’s permission.

Extended interests are further indicated by the broad range of re-tweets used by Aboriginal Twitter users.

Despite these extended interests, though, it is common for seemingly external issues to be tied back to Aboriginal politics and to Indigeneity more broadly. @Numbul1958 links to a news story about a group of academics writing in support of Julia Gillard’s assertion that she has been the victim of misogyny, with a suggestion that racism should take a similar spotlight in the media:

Image 7: Tweet by @Numbul1958.

Image used with @Numbul1958’s permission.

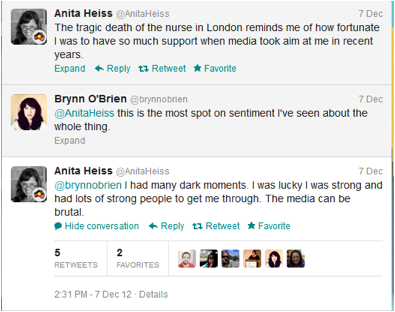

In December 2012, a nurse in London responded to a prank call and revealed private information about the UK Princess, Kate Middleton, who was in hospital with pregnancy-related complications. The nurse committed suicide shortly afterwards. @AnitaHeiss empathises with this, due to her own experience of vilification in the media when she was engaged in public debate with right-wing media commentator Andrew Bolt, who questioned Heiss’s authenticity as an Aboriginal person (Heiss, 2011: n.p.).

Image 8: Twitter dialogue between @AnitaHeiss and @brynnobrien.

Image used with @AnitaHeiss’s permission.

Again, the use of social media for these conversations constructs the identity of the Aboriginal movement as complex and bound up with other struggles, experiences, and causes.

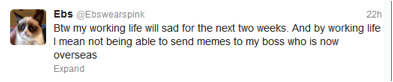

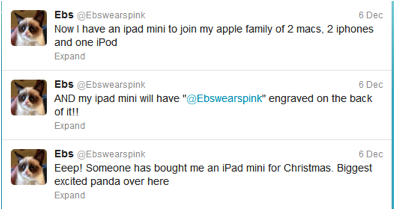

Even for activists, a key use of social media is for everyday, mundane expressions of interests, feelings, and thoughts. This is not explicitly part of the creation of a social movement identity, but is nonetheless bound up in the process of identification and developing involvement of the whole person in the social movement. When people who call themselves ‘Aboriginal activists’ use social media to engage in conversations about their lives, they are speaking to their ‘followers’ and ‘friends’ about what the life of an Aboriginal person is like. This is perhaps the most important mechanism in terms of challenging stereotypes about Indigeneity. Take for example @Ebswearspink, who tweets about the following topics:

Image 9: Tweets from @Ebswearspink.

Images used with @Ebswearspink’s permission.

Ebs is presenting herself here as a person whose life is embedded in technology – she has an “apple family”, and she enjoys sharing internet memes (in fact, Ebs’ profile picture is itself an internet cat meme). She also presents a cosmopolitan image – going to cafes (and relying on EFTPOS facilities). And she cares about her appearance, being “flattered” when people assume she is younger than she is. None of these characteristics exist in the essentialised image of Aboriginal people, which associates remoteness, tradition, dot paintings and dusty landscapes with the everyday reality of Aboriginality. They are all important, then, for the deconstruction of that essentialised image. Although that is unlikely the intent of tweeting about such topics, the effect of this self-writing is still powerful. While the #Itriedtobeauthenticbut hashtag on Twitter did this explicitly, regularly posting everyday thoughts is a process of writing and re-writing oneself “into being on and through online technologies in a constant and up-to-date fashion” (Sauter, 2013: 184). This upsets and challenges stereotypes of Aboriginal identity and opens up a space for a more complex representation of reality.

Self-Writing Relationships

Another innovation offered by social media is the ability to communicate with a broad, accessible, and engaged audience. When books, or even photocopied leaflets, are the primary means of self-writing for an audience, it remains an elite activity. However, internet access has rapidly expanded and diversified (DeLuca, Lawson & Sun, 2012). Even in remote Aboriginal communities, internet access is becoming commonplace (Kral, 2010). This means that now, more than ever, anyone can self-write to a public audience. According to Foucault (1997: 217), self-writing for an audience leads to introspection. This is as important for social movement identities as it is for individuals (Snow & McAdam, 2000). Social movements must remain reflexive to ensure that their structure is relevant to their constituents and their goals (Graeber, 2009).

Social movements have traditionally relied on the mass media to frame their outward appearance (Morris & Staggenborg, 2007: 186). Although they have also utilised multiple forms of self-writing (such as graffiti and pamphleteering), the most cost- and time-effective method of speaking to a broad audience was previously considered to be through mainstream media. Movements can adopt some strategies to influence how they are depicted in the media, but this is ultimately outside of their control (DeLuca et al, 2012). Social media, in effect, allow for a proliferation of voices about a social movement. At the same time, it is not useful to think about online self-writing as somehow separate to offline identification processes. As DeLuca et al (2012: 485) argue,

there is no possible demarcation between the mediated and the real. Mediated worlds are real and reality is always mediated (by media, language, culture, ideologies, and perceptual practices).

Thus, the increasing use of social media by activists should not be viewed as a separate form of activism, or as an altogether new tool of protest.

Online self-writing, given its accessible nature and the ability to reach an audience, is an important tool for continually forming and negotiating identities, whether individual or collective. This identification process through online self-writing is especially powerful for marginalised groups around the world. Aboriginal people have been subjected to more than 200 years of categorisation, by the Australian state, the mainstream media and public opinion (and in some cases, by academia – see Petray, 2012b). Self-writing allows for a more complex version of (individual and collective) Indigeneity to be constructed.

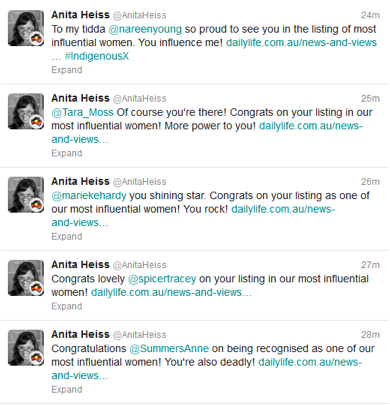

Self-writing is an important way of forming a sense of self for social movements, but it is also a way of positioning the social movement within the world. This means that relationships are written in the same way as collective identity. This is done implicitly, as a self is written and read by others, and is amplified as that writing is shared, through retweeting, commenting, and interactions. Because it is implicit, this interaction tends to follow the norms of other social interaction – it is based on friendship, or interest, and is not necessarily strategic – though the outcomes are beneficial for the movement as a whole. For example, on 11 December, Australian publication Daily Life released an article on the 20 Most Influential Female Voices of 2012. @AnitaHeiss congratulated several of the women featured on the list through her Twitter account.

Image 10: Tweets from @AnitaHeiss.

Image used with @AnitaHeiss’s permission.

Anita is maintaining her relationships with these people, and the tweets also make clear to her own followers that these relationships are important. They also indicate the relationship to the followers of the women mentioned. Given Anita’s avatar, which includes the image of an Australia-shaped Aboriginal flag, followers can see that there are links between these influential (mostly non-Indigenous) women and the Aboriginal movement. Online self-writing effectively blends the personal and the public domain, connecting users in ways that would be difficult in offline forms.

Because the majority of movement self-formation takes place through the social media activity of individuals, rather than organisations, it resembles the personal interactions above rather than an explicit form of public relations. Non-governmental organisations have a tendency to use online public relations to enhance their organisation’s image, with a particular focus on “tapping into current and potential sources of funding” (Seo, Kim & Yang, 2009: 124). So while new forms of media make NGOs less reliant on the mainstream media, the two biggest targets of NGO self-writing are journalists and funders. In contrast, individuals who contribute to the writing of relationships on behalf of the social movement are doing so for personal reasons more prominently than movement reasons. This is likely to reflect well on the movement, as it is clear to observers that the relationships are genuine rather than staged.

An important aspect of social media is the ease with which social movements can create international and inter-movement networks through these genuine interactions. Many of the issues that affect Aboriginal people in Australia are common to Indigenous and ethnic minority groups in other countries: for example, the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people in the justice system, and the subsequent overrepresentation of Aboriginal people who die in police custody. @Numbul1958, a Twitter user in North Queensland, responded to a story about an American police officer being sentenced to prison for using excessive force against a disabled janitor mistakenly accused of stealing money (see also Leibowitz 2012).

Image 11: Twitter conversation between @AboriginalPress and @Numbul1958.

Image used with @Numbul1958’s permission.

International networks are important for social movements, because they allow for a broader exertion of pressure on governments to make changes to the existing structures (Keck & Sikkink, 1998; Chesterman, 2001a; 2001b). Social media makes these international information-sharing and advocacy networks more timely and easier to access by people who cannot necessarily afford to travel to large global conferences and meetings (Smith, 2007).

Social media is also a very useful tool for writing relationships for the ongoing formation of the movement itself. The use of tagging and mentioning other users allows for direct interaction, and potentially broadens the audience. Further, the #hashtag function lets people join conversations about specific issues, which continues to potentially expand the audience. In the tweets above about #Gurrumul, Ebs joined a conversation that included media outlets, music fans, and a range of other Twitter users. It is also common to see Indigenous Twitter users joining broader national conversations through the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC’s) national current affairs discussion program’s #QandA hashtag. #IndigenousX is an ongoing hashtag started by @LukeLPearson used to indicate Indigenous excellence, so it is attached to tweets about accomplishments and events. @BlaykeTatafu demonstrates how both @mentions and #hashtags can function to demonstrate the networks in which the Aboriginal movement are embedded.

Image 12: Tweet from @BlaykeTatafu.

Image used with @BlaykeTatafu’s permission.

These hashtags allow for asynchronous conversations to happen. Others are used to facilitate real-time discussions, such as #iXchat, which has only recently been launched and attempts to provide a forum for regular, real-time discussion of complicated issues that affect Indigenous people. Sometimes this use of within-movement networking is explicit, as @LukeLPearson indicates in this tweet:

Image 13: Tweet from @LukeLPearson.

Image used with @LukeLPearson’s permission.

Attempting to organise a large number of people to watch a documentary at the same time and tweet about it is an attempt to get the hashtag ‘trending’ so it appears on the homepage of all Twitter users. This attempt to broaden the audience is a creative use of social media and an attempt to self-write the relationships within the movement and with outsiders.

Strategic attempts like this that seek to gain an audience raise an important question that must be considered in discussions of social movements’ use of social media: who is reading? Or perhaps more importantly, what happens if no one reads? In a study of the recent history of activism in Egypt which led to the Tahrir Square revolt, Lim (2012: 238) notes that, despite an increase in the numbers of online activists between 2005 and 2007, “conversations and ideas continued to be circulated only within an inner circle of activists and sympathisers”. However, these internal conversations are not trivial – they are important conversations for movements to have, to negotiate their collective identity amongst themselves and to negotiate their relationships with others. So even if the #OurGeneration discussion does not trend, for example, it will still be seen by a large number of people who are already sympathetic to the Aboriginal movement, and by others who may not yet be aware of the issues.

Another important question for movements to consider when they self-write is not only who is reading, but what do they do with the information they read. Rotman et al (2011) point out that there are no direct links between awareness raising and social change. They suggest that a likely outcome of this raised awareness is ‘slacktivism’, rather than activism, by which they mean a “low-risk, low-cost activity via social media, whose purpose is to raise awareness, produce change, or grant satisfaction to the person engaged in the activity” (821). Although, of course, it is more beneficial for movements if they create committed constituents rather than ‘slacktivists’, the definition offered by Rotman et al (2011) is not a negative one in the eyes of many activists. As McAdam and Paulsen (1993) have pointed out, low-cost and low-risk activism is much more likely to attract a diverse audience, so online activism has the benefit of being more accessible to more people. Naming it ‘slacktivism’ comes with an unshakeable value judgement, but a movement with a range of participants, from radical activists to more moderate supporters is more likely to be successful in the long run (Burgmann, 2000).

Conclusions

This paper has explored the way that individual activists’ use of social media for self-writing contributes to the creation and maintenance of collective identity in the Aboriginal movement. Self-writing in online environments allows some Aboriginal activists to contest essentialised stereotypes and present a more nuanced and complex account of Indigeneity. This form of self-writing undermines the need for strategic essentialism, because social media is such a mundane part of everyday life for so many people that its use is not always reflexive. Users do not think, when they tweet about public transport or their lunch break, that they are contesting Indigeneity. This, I have argued, makes social media a powerful tool for normalising social movements. Online self-writing is an important way for social movement participants to communicate to each other and to outsiders about who they are. The importance of social media as a tool for activists to self-write their movement is extended to the relationships they negotiate through its use. Social media allows for the construction of a collective, social movement identity which is constantly negotiated and mediated. It allows for more agency and diversity than was afforded to social movement actors in the past. While representations of Indigeneity are still strongly influenced by the mainstream media, social media allows for parallel, diverse, and complex conversations to occur.

As this paper has demonstrated, Aboriginal people in Australia live in cities as well as rural areas, they visit cafes, they eat chocolate, they have jobs and write books and study at university, and they use the internet to look at funny cat pictures. None of this negates their identification as Aboriginal people. None of this affects their ability to practise tradition or experience Aboriginal culture. As the #Itriedtobeauthenticbut conversation made clear through its use of humour, authenticity and Indigeneity are not undone by geography, technology, or lifestyle. The ubiquity of social media makes it possible for a more complicated idea of what Indigeneity looks like to take a more prominent place in national conversations. The mundane use of social media acts as an innovative and perhaps unintentional form of activism which destabilises long-held assumptions about Aboriginal people.

This paper has taken the well-developed Foucauldian idea of self-writing, extended by Sauter (2013: in press) to social media use, and applied it to the creation of collective, social movement identities. Online self-writing challenges top-down categorisation, so that even mundane comments can become a political act that is heard by a large audience. Much of the work on social movements and social media centres on recent mass protests and revolutions, but movements are created and sustained through far smaller, everyday processes and practices. This provides impetus for further research; for example, by comparing the experience and impacts of social media and community-based Indigenous media to understand how shifting and developing technologies are changing the ways in which media is used to mediate the Aboriginal social movement.

Endnotes

1 Throughout this paper, I use the terms ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘Indigenous’. Wherever it is possible to be specific, I rely on ‘Aboriginal’ as a more descriptive and preferable term. Where discussion refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, or where this cannot be determined, I use ‘Indigenous’.

2 Sauter (in press) traces the history of self-writing, which included Ancient Greek askesis, or recording and reflecting on experiences, Christian diarising as a form of confessional, and writing as a therapeutic tool in psychotherapy. Other historical forms of self-writing were written with an audience in mind, for example letter writing through which writers “present[ed] themselves to the gaze of another” (Sauter, in press, p.6), Romantic-era autobiography, and more recently, social media.

Acknowledgments

This paper has benefited from the feedback of Theresa Sauter, the staff and students who attended a seminar presentation, and the two reviewers. Thanks to the special issue editors for including my paper in this collection. This research was funded by a James Cook University Rising Star grant.

References

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2005). Face the Facts. Retrieved from http://humanrights.gov.au/racial_discrimination/face_facts_05/atsi.html

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Methods. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Brubaker, R. & Cooper, F. (2000). Beyond ‘Identity’. Theory and Society 29(1):1-47.

Bukstein, G. (2008). A Time of Opportunities: The Piquetero Movement and Democratization in Argentina. In Raventos, C. (Ed.), Democratic Innovation in the South: Participation and Representation in Asia, Africa and Latin America (pp.123-140). Buenos Aires: Clacso.

Burgmann, V. (2000). The Point of Protest: Advocacy and Social Action in Twentieth Century Australia. Just Policy September: 7-15.

Burgmann, V. (2003). Power, Profit and Protest: Australian Social Movements and Globalisation. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Chesterman, J. (2001a). Defending Australia’s Reputation: How Indigenous Australians won Civil Rights, Part One. Australian Historical Studies 116:20-39.

Chesterman, J. (2001b). Defending Australia’s Reputation: How Indigenous Australians won Civil Rights, Part Two. Australian Historical Studies 117:201-221.

Cowlishaw, G. (2004). Racial Positioning, Privilege and Public Debate. In Moreton-Robinson, A. (Ed.), Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

DeLuca, K.M., Lawson, S., & Sun, Y. (2012). Occupy Wall Street on the Public Screens of Social Media: The Many Framings of the Birth of a Protest Movement. Communication, Culture & Critique 5: 483-509.

Dodson, M. (1997). Citizenship in Australia: An Indigenous Perspective. Alternative Law Journal 22(2): 57-59.

Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the self. In L.H. Martin, H. Gutman & P.H. Hutton (Eds.), Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault (pp.16-49). London: University of Massachusetts Press.

Foucault, M. (1997). Self-Writing. In Rabinow, P. (Ed.), Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth – The Essential Works of Michel Foucault, 1954-1984 (pp.207-222). New York: New Press.

Friedman, D. & McAdam, D. (1992). Collective Identity and Activism: Networks, Choices, and the Life of a Social Movement. In Morris, A.D. & McClurg, C. (Eds.), Frontiers in Social Movement Theory (pp.156-173). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Graeber, D. (2009). Direct Action: An Ethnography. Oakland: AK Press.

Heiss, A. (2011). My Statement on Today’s Win in the Federal Court! Anita Heiss Blog. Retrieved from http://anitaheissblog.blogspot.com.au/2011/09/my-statement-on-todays-in-in-federal.html

Hunt, S.A. & Benford, R.D. (2007). Collective Identity, Solidarity, and Commitment. In Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., & Kriesi, H. (Eds), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (pp.433-457). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Kavada, A. (2010). Email Lists and Participatory Democracy in the European Social Forum. Media, Culture & Society 32(3):355-372.

Keck, M. & Sikkink, J. (1998). Activists Beyond Borders. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Klandermans, B. (2007). The Demand and Supply of Participation: Social-Psychological Correlates of Participation in Social Movements. In Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., & Kriesi, H. (Eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (pp.360-379). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Kral, I. (2010). Plugged In: Remote Australian Indigenous Youth and Digital Culture. CAEPR Working Paper 69. Canberra: ANU.

Landzelius, K. (2006). The Meta-Native and the Militant Activist: Virtually Saving the Rainforest. In Landzelius, K. (Ed.), Native on the Net: Indigenous and Diasporic Peoples in the Virtual Age (pp.112-131). New York: Routledge.

Langton, M. (1981). Urbanizing Aborigines: The Social Scientists’ Great Deception. Social Alternatives 2(2):16-22.

Leibowitz, B. (2012, November 16). Spokane Police Officer Jailed in Beating Death of Disabled Janitor. CBS News. Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-504083_162-57551352-504083/spokane-police-officer-jailed-in-beating-death-of-disabled-janitor/

Lim, M. (2012). Clicks, Cabs, and Coffee Houses: Social Media and Oppositional Movements in Egypt, 2004-2011. Journal of Communication 62:231-248.

Maddison, S. (2009). Black Politics: Inside the Complexity of Aboriginal Political Culture. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Mansell, M. (2003) ‘The Decline of a Movement’. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues 6(4): 27-29.

McAdam, D. & Paulsen, R. (1993). Specifying the Relationship Between Social Ties and Activism. The American Journal of Sociology 99(3):640-667.

Merlan, F. (2005). Indigenous Movements in Australia. Annual Review of Anthropology 34:473-494.

Merlan, F. (2009). Indigeneity: Global and Local. Current Anthropology 50(3):303-333.

Morris, A. & Staggenborg, S. (2007). Leadership in Social Movements. In Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., & Kriesi, H. (Eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (pp.171-196). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Paradies, Y.C. (2006). Beyond Black and White: Essentailism, Hybridity and Indigeneity. Journal of Sociology 42(4):355-367.

Petray, T. (2010). Actions, Reactions, Interactions: The Townsville Aboriginal Movement and the Australian State (PhD Thesis). James Cook University, Townsville, QLD.

Petray, T. (2012a). Protest 2.0: Online Interactions and Aboriginal Activists. Media, Culture & Society 33(6):923-940.

Petray, T. (2012b). Can Theory Disempower? Making Space for Agency in Theories of Indigenous Issues. In Howard-Wagner, D., Habibis, D. & Petray, T. (Eds), Theorising Indigenous Sociology: Australian Perspectives. Sydney: Sydney University eScholarship Repository.

Reynolds, H. (2005). Nowhere People. Camberwell, VIC: Viking.

Rotman, D., Preece, J., Vieweg, S, Shneiderman, B., Yardi, S., Pirolli, P., Chi, E.H., & Glaisyer, T. (2011). From Slacktivism to Activism: Participatory Culture in the Age of Social Media. CHI (May 7-12):819-822.

Rowse, T. (2000). Transforming the Notion of the Urban Aborigine. Urban Policy and Research 18(2):171-190.

Sauter, T. (2013). Governing Self on Facebook: Social Networking Sites as Tools for Self-Formation (PhD Thesis). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

Sauter, T. (in press). ‘What’s on your mind?’: Writing on Facebook as a Tool for Self-Formation. New Media and Society.

Sauter, T. and Kendall, G. (2011). Parrhesia and democracy: Truthtelling, WikiLeaks and the Arab Spring. Social Alternatives 30(3):10-14.

Seo, H., Kim, J.Y., & Yang, S. (2009). Global Activism and New Media: A Study of Transnational NGOs’ Online Public Relations. Public Relations Review 35:123-126.

Smith, J. (2007). Transnational Processes and Movements. In Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., & Kriesi, H. (Eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (pp.311-335). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Snow, D.A. (2001). Collective Identity and Expressive Forms. In Smelser, N.J and Baltes, P.B. (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp.196-254). London: Elsevier Science.

Snow, D.A. (2007). Framing Processes, Ideology, and Discursive Fields. In Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., & Kriesi, H. (Eds), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (pp.380-412). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Snow, D.A. & McAdam, D. (2000). Identify Work Processes in the Context of Social Movements: Clarifying the Identity/Movement Nexus. In Stryker, S., Owens, T.J., & White, R.W. (Eds.), Self, Identity, and Social Movements (pp.41-67). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., & Kriesi, H. (2007). Mapping the Terrain. In Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., & Kriesi, H. (Eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (pp.3-16). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Speed, S. (2006). At the Crossroads of Human Rights and Anthropology: Toward a Critically Engaged Activist Research. American Anthropologist 108(1):66-76.

Spivak, G.C. (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak? In Nelson, C. & Grossberg, L. (Eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. London: Macmillan.

Tatafu, B. (2012a, March 20). Hello! Halcyon Days. Retrieved from http://www.blaketatafu.blogspot.com.au/2012/03/hello-to-all-that-will-be-reading-my.html

Tatafu, B. (2012b, April 8). Australian Pop in 2012. Halcyon Days. Retrieved from http://www.blaketatafu.blogspot.com.au/search?updated-max=2012-05-25T02:09:00-07:00&max-results=1&start=1&by-date=false

Tatafu, B. (2012c, 25 May). Lions Make You Brave. Halcyon Days. Retrieved from http://www.blaketatafu.blogspot.com.au/search?updated-max=2012-07-26T09:46:00-07:00&max-results=1

Vasek, L. (2012, November 13). Abbott wants ‘authentic’ outback Aborigines in Coalition with Wyatt. The Australian. Retrieved from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/more-authentic-aboriginal-mps-needed-tony-abbott-says/story-fn59niix-1226515871824

Zhao, S., Grasmuck, S. & Martin, J. (2008). Identity Construction on Facebook: Digital Empowerment in Anchored Relationships. Computers in Human Behavior 24:1816-1836.

About the author

Dr Theresa Petray teaches sociology at James Cook University in Townsville. This article and her current work on Aboriginal social media usage as a tool of activism builds on her PhD work, completed in 2011, on Aboriginal activism in North Queensland. Dr Petray is the Secretary of The Australian Sociological Association, the co-convenor of the Sociology of Indigenous Issues thematic group, and a member of the Indigenous Studies Research Network.